Abstract

Thermally oxidized oil generates reactive oxygen species that have been implicated in several pathological processes including hypertension. This study was to ascertain the role of inflammation in the blood pressure raising effect of heated soybean oil in rats. Male Sprague-Dawley rats were divided into four groups and were fed with the following diets, respectively, for 6 months: basal diet (control); fresh soybean oil (FSO); five-time-heated soybean oil (5HSO); or 10-time-heated soybean oil (10HSO). Blood pressure was measured at baseline and monthly using tail-cuff method. Plasma prostacyclin (PGI2) and thromboxane A2 (TXA2) were measured prior to treatment and at the end of the study. After six months, the rats were sacrificed, and the aortic arches were dissected for morphometric and immunohistochemical analyses. Blood pressure was increased significantly in the 5HSO and 10HSO groups. The blood pressure was maintained throughout the study in rats fed FSO. The aortae in the 5HSO and 10HSO groups showed significantly increased aortic wall thickness, area and circumferential wall tension. 5HSO and 10HSO diets significantly increased plasma TXA2/PGI2 ratio. Endothelial VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 were significantly increased in 5HSO, as well as LOX-1 in 10HSO groups. In conclusion, prolonged consumption of repeatedly heated soybean oil causes blood pressure elevation, which may be attributed to inflammation.

Keywords: cell adhesion molecules, heating, hypertension, inflammation, prostacyclin, Soybean oil, thromboxane A2

Hypertension is a common health problem worldwide. According to the World Health Organization's Global Health Risks 2009; hypertension accounts for 13% of mortality globally. It is the major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, including heart failure (Iyer et al. 2010). Dietary factors have been known to be playing an important role in hypertension. For instance, the consumption of a Mediterranean diet with an abundant source of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) from olive oil might reduce the prevalence of hypertension (Alonso et al. 2006). Nevertheless, the quality of vegetable oils consumed in the diet might also affect blood pressure. Vegetable oils are usually served in the thermally oxidized state because of the heat exposure during food preparation. Soriguer et al. 2003 reported that the risk of hypertension was positively associated with the intake of cooking oil polar compounds.

Deep frying has become one of the most commonly used methods of the food preparation. In today's time deficient lifestyle, deep fried foods are gaining more popularity in daily diet because of their desirable sensory characteristics (Boskou et al. 2006). Deep frying is defined as the process of cooking foods by immersing them in edible oil at the temperature of 150–200 °C (Yamsaengsung & Moreira 2002). At the same time, the vegetable oils are also exposed to the air and moisture, in which they undergo a complex series physical and chemical deterioration known as ‘lipid oxidation’, like hydrolysis, polymerization and isomerization. This oxidative deterioration affects the chemical compositions of the vegetable oils by oxidizing its fatty acids (Marmesat et al. 2008), decreasing the free radical scavenging vitamin E contents (Rossi et al. 2007) and generating polar compounds and polymeric products (Romero et al. 2006; Bansal et al. 2010). In combination, these lipid oxidation products are detrimental to the endothelial cells. Moreover, during deep-frying process, it is common for the vegetable oils to be re-used repeatedly to cut the cost.

The oxidation products may disturb the redox steady state (Boueiz & Hassoun 2009), causing an imbalance between the vasodilator prostacyclin (PGI2) and vasoconstrictor thromboxane A2 (TXA2) (Muzaffar et al. 2011). PGI2 protects against elevated blood pressure and leucocytes adhesion, and it is therefore considered to be cardioprotective. On the contrary, TXA2 amplifies platelet aggregation and triggers vasoconstriction, counteracting the effect of PGI2. Hypertension is associated with an imbalance between the vasoactive substances (Yamada et al. 1999). Additionally, excessive oxidant might cause inflammation, which may as well play an imperative part in the pathogenesis of hypertension (Ghanem & Movahed 2007). Endothelium is the major regulator of vascular health as well as the primary target of immunological attack in inflammatory responses. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor (LOX-1) are expressed by endothelium and are up-regulated in response to inflammatory insult (Chen et al. 2002; Kim et al. 2011). VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 mediate leucocytes binding to the endothelium. Infiltration of inflammatory molecules may disturb the normal function of endothelium in regulating blood pressure. On the other hand, enhanced expression of LOX-1, which acts as a cell receptor for endocytosis of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (Ox-LDL), may attenuate the endothelial function and cause hypertension (Ogura et al. 2009).

Long-term intake of meal containing repeatedly heated oil has been reported to cause an increase in blood pressure (Leong et al. 2008). The present study was undertaken to investigate the possible inflammatory mechanisms involved in the increase in blood pressure following prolonged consumption of repeatedly heated soybean oil in experimental rats. We compared the effects between fresh, five-time-heated (5HSO) and 10-time-heated (10HSO) oils to see whether the changes were affected by the reheating frequency.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

Twenty-four male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 24) aged 3 months, weighing 200–280 g were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Resource Unit, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. The rats were housed in stainless steel cages and kept at room temperature of 27 ± 2 °C at Pharmacology Department Animal House. All rats had free access to food and tap water throughout the experiment. The handling and experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Animal Ethics Committee.

Ethical approval

FP/FAR/2008/KAMSIAH/9-APR/220-APR-2008-FEB-2011 (UFMG) (protocol 122/2008).

Soybean oil source and experimental diets preparation

Commercially purchased soybean oil (Sunbeam, Sime Darby Edible Products Limited, Singapore) was used in fresh state or heated five times or 10 times, based on the method described by Owu et al. 1998 with some modifications. Briefly, 2.5 l of fresh soybean oil (FSO) was heated to 180 °C in a stainless steel wok and used to fry 1 kg of peeled and sliced sweet potatoes for 10 min. The heated oil was allowed to cool for 5 h prior to the next frying. The entire frying process was repeated four and nine times to obtain 5HSO and 10HSO, respectively, with a fresh batch of sliced sweet potatoes. No replenishment of fresh oil was carried out between batches to make up for the loss because of uptake of the oil by the frying material. Standard rat chow (Gold Coin, Kepong, Malaysia) was ground and formulated by mixing 15% weight/weight (w/w) of respective oils prepared. The mixture was moulded into pellets and dried in an oven at 80 °C overnight. The prepared diets were then kept in plastic packets to prevent from air and moisture.

Measurement of peroxide value

The peroxide value of oil was determined according to the American Oil Chemists' Society (AOCS) standard titration method (Official method Cd 8-53). It was expressed as mille-equivalents of active oxygen per kilogram of oil sample, mEq O2/kg.

Study design

After a week of acclimatization, the rats were randomly divided into four groups, namely one control and three experimental groups with six rats per group. The control group was fed rat chow only without any addition of oil. The three experimental groups were fed basal diet fortified with 15% w/w of FSO, 5HSO or 10HSO respectively for 6 months. The body weight and food intake were measured weekly during the study period. Blood pressure was measured at baseline and monthly. Blood was sampled prior to treatment and at the end of the treatment. The blood was then centrifuged to obtain plasma for further biochemical tests. At the end of the study, rats were sacrificed, and aortic arches were excised. The specimens were rapidly isolated from adherent adipose and connective tissues. The aortae were then processed according to the routine histological procedures for histological and immunohistochemical purposes (Hewitson et al. 2010).

Measurement of blood pressure

Systolic blood pressure of rats was measured by the non-invasive tail-cuff method using PowerLab data acquisition systems (ADI Instruments, Bella Vista, NSW, Australia) after warming the rats for 10 min. Five readings were obtained from each rat, and systolic blood pressure was averaged.

Measurement of prostacyclin metabolites

Plasma PGI2 was measured as the concentration of 6-keto prostaglandin F1α (6-keto-PGF1α), a stable metabolite of PGI2. It was determined by using commercially available kits (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. The developed colour intensity was measured at 412 nm on Emax ELISA microplate reader using the softmax pro Software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Measurement of thromboxane A2 metabolites

TXA2 production was measured by its metabolites thromboxane B2 (TXB2). Enzyme immunoassay kits (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) were used to measure the plasma level of TXB2 as described by the manufacturer. The intensity of coloured product was measured at a wavelength of 412 nm on Emax ELISA microplate reader using the softmax pro Software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Microscopic examination of aortic wall

Aortic arches were embedded in Paraplast Plus (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and 5-μm transverse sections were accomplished (Leica RM2235, Walldorf, Germany) and adhered to glass slides. The sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to identify the nuclei and vascular smooth muscle cells. Aortic sections were also stained with Verhoeff–van Gieson (VVG) to identify elastic fibres and smooth muscle cells. All sections were examined under a light microscope.

Measurement of aortic morphometry

Images of five non-consecutive VVG-stained aortic sections per animal were captured (JPEG format, 24-bit colour, 2560 × 1920 pixels) using a micropublisher 5.0 RTV camera (Q Imaging, Surrey, BC, Canada) and a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The images were analysed using the software image-pro Plus version 7.0 (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA). Morphometric measurements including aortic wall thickness, aortic wall area, lumen diameter, elastic lamellae number, circumferential wall tension (CWT) and tensile stress (TS) were determined according to the method described by Fernandes-Santos et al. 2009.

On the other hand, the aortic sections stained with H&E were used to measure the number of smooth muscle cell nuclei in tunica media and the mean area of each nucleus. This was carried out according to described methods with some modifications (Levy et al. 1996; Zaina & Pettersson 2001). The image was segmented into a new binary image, where the black colour represented the nuclei. Before calculation, any artefact or particles under the predetermined size were eliminated. The number of cell nuclei and area of each of them were then calculated within four fields of approximately 10,000 μm2 at 0°, 90°, 180° and 270° on each section. In all cases, values obtained from each spot were pooled and averaged to obtain the individual value for each section.

Immunohistochemical staining of VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and LOX-1

Before immunohistochemically staining the aortic sections, a control experiment was performed on a known positive tissue to evaluate the optimal antigen retrieval time and conditions (pH, antibody concentration and incubation duration) for the particular primary antibodies being used. Microwave heat-induced antigen retrieval method was applied to unmask the epitope.

Paraffin-embedded aortic rings were transversely sectioned at the thickness of 5 μm and adhered to poly-lysine precoated glass slides (Polysine, Thermo Scientific, Braunschweig, Germany). The sections were baked at 40 °C overnight before being deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in graded alcohols. After that, the sections were subjected to the respective microwave antigen retrieval methods. The sections were then cooled in running tap water for 10 min. A micropolymeric labelling method was applied in the immunohistochemical staining by using the UltraVision Quanto kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Fermont, CA, USA). All steps were carried out in humidified chambers to prevent drying of the tissues.

Briefly, the sections were incubated with hydrogen peroxide to block endogenous peroxidase and followed by Ultra V Block to reduce non-specific background staining. The aortic sections were then incubated with respective primary antibodies at room temperature for an hour: a rabbit polyclonal antibody anti-rat VCAM-1 (diluted 1:100, sc-8304; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA); or a mouse monoclonal antibody anti-rat ICAM-1 (diluted 1:50; NB500-318; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA); or a rabbit polyclonal anti-rat LOX-1 (diluted 1:100; NB500-318; Novus Biologicals). The reaction was amplified with primary antibody amplifier, followed by HRP Polymer. Antibody binding was visualized with diaminobenzidine (DAB) and counterstained with haematoxylin. All sections were cover-slipped and mounted with DPX mounting medium. The slides were left to dry in the fume hood before quantification.

Quantification of VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and LOX-1 immunostaining

Immunostaining of VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and LOX-1 were quantified as described by Moraes-Teixeira et al. 2010. Digital images were acquired (JPEG format, 24-bit colour, 2560 × 1920 pixels) with a MicroPublisher 5.0 RTV camera (Q Imaging, Surrey, BC, Canada) and a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and analysed with the software image-pro Plus version 7.0 (Media Cybernetics). Briefly, intima and media of the entire aortic ring were divided into several fields. The immunostaining was selected and segmented into a new binary image, where white colour represented immunostaining and black colour represented unstained area. Tunica intima boundary was delimited using an irregular ‘area of interest’ tool. The percentage of area that was occupied by white colour (i.e. the immunostaining) inside the delimited tunica intima was quantified using the image histogram tool (Mandarim-de-Lacerda et al. 2010). Immunostaining was expressed as the percentage of tunica intima area (%). Measurements were obtained from five non-consecutive aortic sections from each animal.

Statistical analysis

All results were presented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). The normality of data was first determined by using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Paired Student's t-test was used to analyse the level differences between pre- and post-treatment data for the same group. To compare the results amongst the experimental groups, one-way analysis of variance (anova) followed by Tukey's honestly significant differences (HSD) post hoc test was performed. The correlations between parameters were analysed with Pearson's correlation test. A value of P < 0.05 was adopted as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the software spss version 14.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

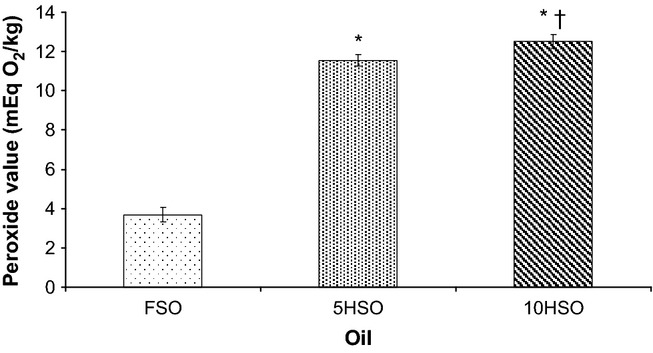

Peroxide value of oil

Peroxide value in the oil was increased after being repeatedly heated. 5HSO and 10HSO both showed significantly increased peroxide values (P < 0.05) compared to the fresh oil. In addition, peroxide values in 10HSO was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than in 5HSO (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Peroxide value in oil. Data are average of three estimations (mean ± SEM). FSO, fresh soybean oil; 5HSO, five-time-heated soybean oil; 10HSO, ten-time-heated soybean oil. *Significantly different (P < 0.05) compared to FSO; †Significantly differently (P < 0.05) compared to 5HSO.

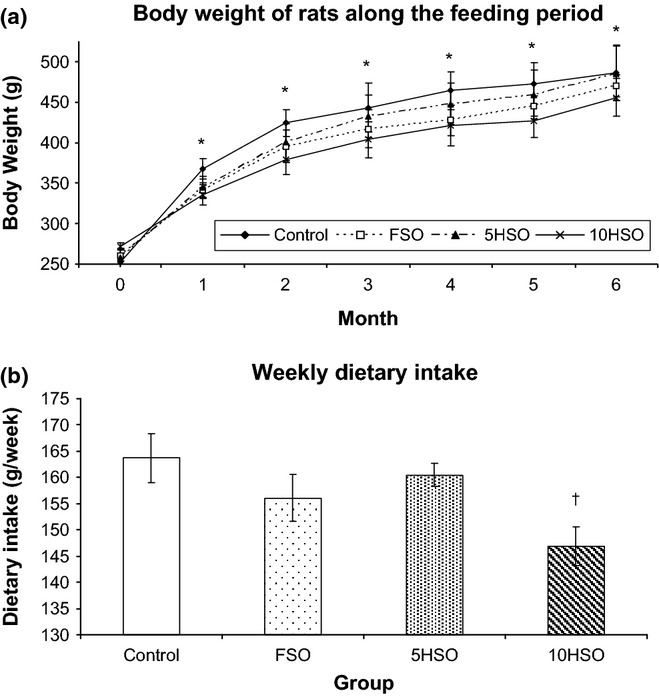

Growth performance

As shown in Figure 2, the animals from all the experimental groups exhibited good growth performance, with a gradual increase in body weight along the experimental period. By the end of the study, the body weight of rats was significantly different (P < 0.05) than their respective initial body weight. FSO and 5HSO groups did not show different weekly dietary intake than the control. However, the weekly dietary intake of 10HSO group was significantly decreased (P < 0.05) compared to the control.

Figure 2.

Growth performance of rats throughout the study period. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. FSO, fresh soybean oil; 5HSO, five-time-heated soybean oil; 10HSO, ten-time-heated soybean oil. *Significantly different (P < 0.05) between pre- and post-treatment body weight for same group. †Significantly different (P < 0.05) compared to control.

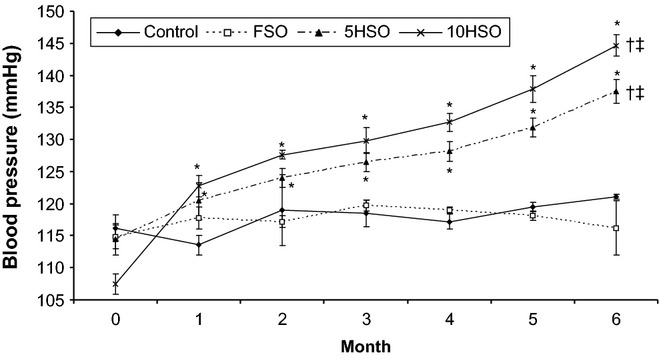

Blood pressure

There was a significant increase in blood pressure after 6 months of feeding with 5HSO or 10HSO (P < 0.05). The increase in blood pressure was observed starting from month 1 and to the end of the study. The increments for 5HSO and 10HSO groups were 20% and 33% compared to the initial blood pressure respectively. At the end of the experiment, the blood pressure in rats fed 5HSO or 10HSO was significantly higher (P < 0.05) compared to the control and FSO groups. On the other hand, the blood pressure of the control and FSO groups did not change significantly throughout the experiment (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Blood pressure of rats throughout the study period. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. FSO, fresh soybean oil; 5HSO, five-time-heated soybean oil; 10HSO, ten-time-heated soybean oil. *Significantly different (P < 0.05) between pre- and post-treatment values for same group; †Significantly different (P < 0.05) compared to the control; ‡Significantly different (P < 0.05) compared to the FSO group.

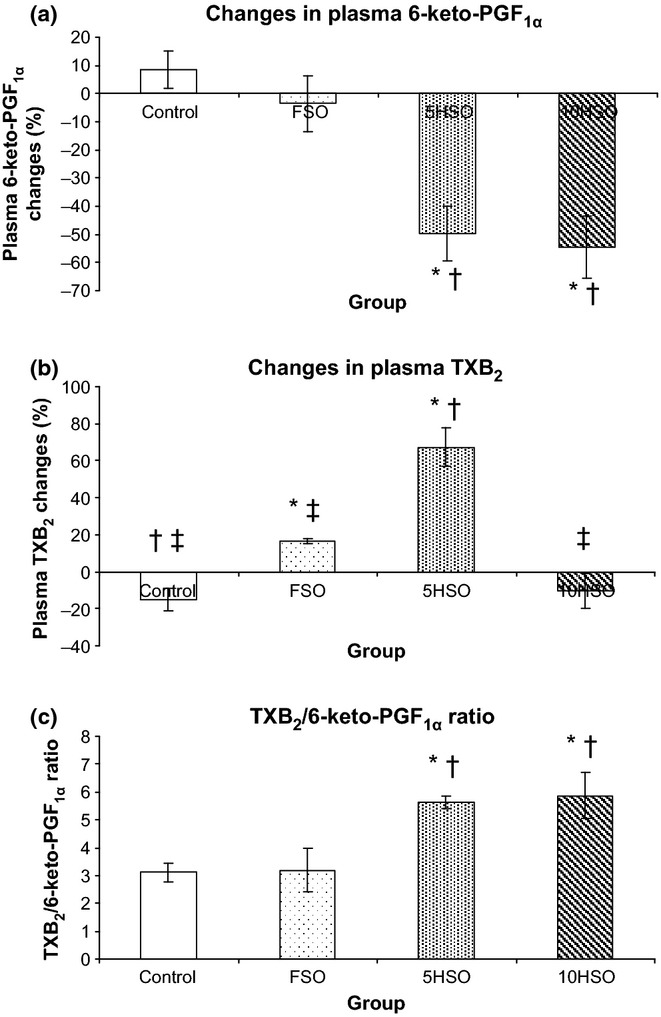

Changes of plasma prostanoids

There was a significant reduction in 6-keto-PGF1α concentration in the rats fed 5HSO or 10HSO compared to the control and FSO groups (P < 0.05). The percentage of reduction in 6-keto-PGF1α for 5HSO and 10HSO groups was 50% and 55%, respectively, compared to the baseline values. However, there was no significant difference in 6-keto-PGF1α concentration observed in the FSO and control groups. FSO and 5HSO increased the plasma level of TXB2 in rats, with 17% and 67% increment respectively. However, 5HSO group showed significantly increased (P < 0.05) TXB2 compared to the other groups. In contrast, TXB2 was decreased in 10HSO group (a reduction of 10% compared to the baseline). Nevertheless, both 5HSO and 10HSO significantly increased (P < 0.05) the TXB2/6-keto-PGF1α ratio in the rats compared to the control and FSO groups (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Changes in plasma prostanoids in rats after 6-month feeding period. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. FSO, fresh soybean oil; 5HSO, five-time-heated soybean oil; 10HSO, ten-time-heated soybean oil; TXB2, thromboxane B2; 6-keto-PGF1α, 6-keto prostaglandin F1α. *Significantly different (P < 0.05) compared to the control; †Significantly different (P < 0.05) compared to the FSO group; ‡Significantly different (P < 0.05) compared to the 5HSO group.

Morphometry and histology of aortic wall

The aortic wall of the rats that had been fed 5HSO or 10HSO showed significantly increased (P < 0.05) thickness, area and CWT compared to the control and FSO groups. Lumen diameter, elastic lamellar number and TS did not differ significantly amongst the groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Aortic morphometric measurements

| Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | FSO | 5HSO | 10HSO | |

| Aortic wall thickness (μm) | 105.594 ± 1.995 | 111.920 ± 3.642 | 130.132 ± 1.994*,† | 140.127 ± 6.049*,† |

| Aortic wall area (mm2) | 0.476 ± 0.015 | 0.526 ± 0.031 | 0.665 ± 0.021*,† | 0.685 ± 0.036*,† |

| Lumen diameter (mm) | 1.330 ± 0.026 | 1.378 ± 0.042 | 1.446 ± 0.030 | 1.417 ± 0.045 |

| Lamellar number | 10.333 ± 0.670 | 10.362 ± 0.438 | 9.612 ± 0.238 | 10.638 ± 0.320 |

| CWT (104 dyne/cm) | 1.048 ± 0.057 | 1.032 ± 0.076 | 1.282 ± 0.043*,† | 1.312 ± 0.022*,† |

| TS (104 dyne/cm2) | 99.381 ± 5.492 | 91.739 ± 4.740 | 95.930 ± 3.632 | 100.504 ± 5.960 |

| Nuclei count (number per 10,000 μm2 field) | 36.556 ± 4.110 | 29.750 ± 2.281 | 36.500 ± 3.608 | 34.833 ± 1.927 |

| Nuclei size (μm2) | 17.649 ± 1.481 | 18.952 ± 0.526 | 19.251 ± 1.825 | 20.535 ± 1.512 |

Results are presented as mean ± SEM. FSO, fresh soybean oil; 5HSO, five-time-heated soybean oil; 10HSO, ten-time-heated soybean oil; CWT, circumferential wall tension; TS, tensile stress.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) compared to the control.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) compared to the FSO group.

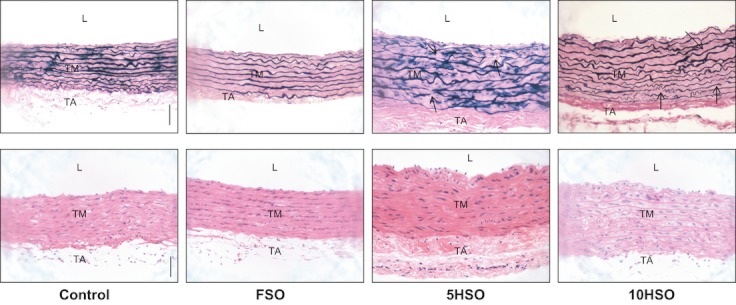

Figure 5 demonstrates the aortic sections stained with VVG or H&E. Elastic lamellae in the control and FSO groups were homogenous and parallel without disrupted lamellae. However, there was disarray and fragmentation of elastic lamellae in the tunica media of 5HSO and 10HSO groups compared to the control and FSO groups. On the other hand, smooth muscle cell nuclei were stained purple with H&E and located between elastic lamellae. There was no significant difference observed in the number of smooth muscle cell nuclei and the nuclei size amongst the groups. However, we observed an increasing pattern in nuclear size from the control to the 10HSO group (Table 1).

Figure 5.

Photomicrographs of aortic sections stained with VVG or H&E. Aortic wall in 5HSO and 10HSO groups is thicker than the control and FSO groups, with an increased interlamellar space. Note the disorganization and fragmentation of the elastic lamellae in the VVG-stained tunica media (arrows). L, lumen; TM, tunica media; TA, tunica adventitia; FSO, fresh soybean oil; 5HSO, five-time-heated soybean oil; 10HSO, ten-time-heated soybean oil. (Magnification = ×200; calibration bar = 50 μm).

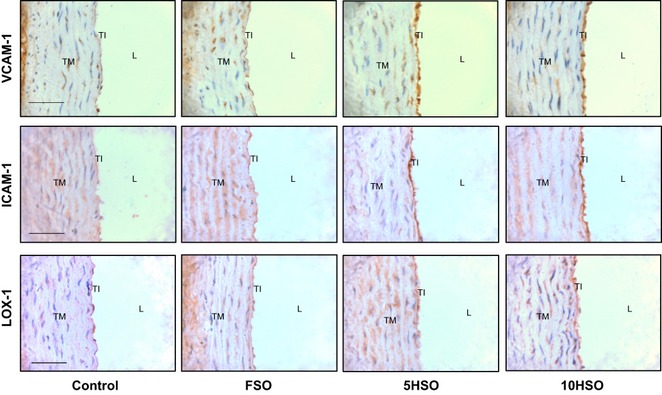

Expression of VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and LOX-1 in aorta

There were significant increases (P < 0.05) in VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 expressions in both 5HSO and 10HSO groups compared to the control and FSO groups. Similarly, there was a significant increase (P < 0.05) in LOX-1 expression in 10HSO-fed rats compared to the control and FSO groups. However, the expression in 5HSO group did not differ significantly when compared with the control and FSO groups. There was no significant difference found between the control and FSO groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Immunohistochemical analyses of adhesion molecules in aorta

| Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | FSO | 5HSO | 10HSO | |

| VCAM-1 | 16.66 ± 1.17 | 14.44 ± 0.42 | 29.15 ± 1.03*,† | 36.87 ± 4.15*,† |

| ICAM-1 | 19.33 ± 2.62 | 16.35 ± 1.45 | 38.53 ± 4.82*,† | 48.66 ± 3.84*,† |

| LOX-1 | 8.61 ± 2.13 | 10.00 ± 1.58 | 14.87 ± 1.58 | 15.81 ± 1.87* |

Results are expressed in% of tunica intima area and presented as mean ± SEM. FSO, fresh soybean oil; 5HSO, five-time-heated soybean oil; 10HSO, ten-time-heated soybean oil; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; LOX-1, lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) compared to the control.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) compared to the FSO group.

As demonstrated in Figure 6, aortic sections from rats fed 5HSO or 10HSO showed remarkably intense staining of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 of the tunica intima compared to the control and FSO groups in which the aortic sections showed relatively little staining. In addition, the aortic section of 10HSO group showed relatively stronger immunostaining for LOX-1 compared to the control and FSO groups.

Figure 6.

Photomicrographs of aortic sections showing immunohistochemical staining for VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and LOX-1. L, lumen; TI, tunica intima; TM, tunica media; TA, tunica adventitia; FSO, fresh soybean oil; 5HSO, five-time-heated soybean oil; 10HSO, ten-time-heated soybean oil; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; LOX-1, lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor. (Magnification = ×400; calibration bar = 50 μm).

Correlation between parameters

Table 3 summarises the correlations between the parameters. There were significant positive correlations between the blood pressure and VCAM-1 (r = 0.691, P < 0.01); ICAM-1 (r = 0.879, P < 0.01); LOX-1 (r = 0.677, P < 0.01); and TXB2/6-keto-PGF1α ratio (r = 0.557, P < 0.01). In addition, the TXB2/6-keto-PGF1α ratio was found to be significantly correlated with VCAM-1 (r = 0.595, P < 0.01); ICAM-1 (r = 0.603, P < 0.01); as well as LOX-1 (r = 0.453, P < 0.05). LOX-1 expression was found to be significantly correlated with VCAM-1 (r = 0.368, P < 0.05) and ICAM-1 (r = 0.590, P < 0.01).

Table 3.

Correlations between parameters

| Blood pressure | TXB2/6-keto-PGF1α ratio | LOX-1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VCAM-1 | 0.691† | 0.595† | 0.368* |

| ICAM-1 | 0.879† | 0.603† | 0.590† |

| LOX-1 | 0.677† | 0.453* | - |

| TXB2/6-keto-PGF1α ratio | 0.557† | - | - |

VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; LOX-1, lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor; TXB2, thromboxane B2; 6-keto-PGF1α, 6-keto prostaglandin F1α.

significant correlation at p < 0.05.

significant correlation at p < 0.01.

Discussion

Repeated heating of soybean oil has been shown to diminish the protective effects of the oil (Adam et al. 2008). The lipid oxidation of the heated oil might induce vascular inflammation and disturb blood pressure regulation. Soybean oil was used in this study because it is an important source of edible vegetable oil. According to the database by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) in United States Department of Agriculture. 2010; the total world consumption of vegetable oil in 2010/2011 was 146.01 million metric tonnes (Mt), which including 41.67 Mt soybean oil.

We observed that the extent of lipid oxidation in soybean oil was influenced by the frequency of frying. The more frequently the soybean oil was reheated, the higher the peroxide value in the oil. The process of heating the cooking oil repeatedly increases the thermal degradation of the oil as reported in the studies by Juárez et al. (2011). Peroxide value is a useful method to determine the quality of oil. It is an index to measure the concentration of hydroperoxide, which is formed during lipid oxidation (Gotoh & Wada 2006). Like other lipid oxidation products, hydroperoxide is considered to be one of the reactive oxygen species (Boueiz & Hassoun 2009). We believe that peroxide value, at least in part, indicates the amount of reactive oxygen species present in the oil as well as the degree of oxidative deterioration.

In the present study, prolonged consumption of FSO, 5HSO or 10HSO did not retard the growth performance of the rats, as there was a significant increase in body weight at the end of the study for all the groups. However, rats fed diet fortified with 10HSO showed significantly lower dietary intake compared to the other groups. Dietary preference is influenced by the sensory properties of the food, such as its taste, smell, colour and texture (Larsen et al. 2011). During the process of deep frying, the oil undergoes a spectrum of deleterious reactions such as oxidation, hydrolysis and polymerization that degrade the quality of the oil. Oxidation, especially, is responsible for the development of rancid flavour in the oil. This situation spoils its palatability and taste, which may be responsible for the lower dietary intake in 10HSO groups. Moreover, fortification of heated oil may affect the digestibility and absorption in the experimental animals (Burenjarga & Totani 2008).

FSO had no significant effect on blood pressure in the rats throughout the experimental period. Ribeiro et al. 2010 also demonstrated similar results in rats fed soybean oil. The studies by Radaelli et al. 2006 and Erkkilä et al. 2008 reported that soybean oil, which is rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), is thought to be beneficial to cardiovascular health. The abundance of α-linolenic acid, an n-3 essential fatty acid in soybean oil may be responsible for this effect (Nadtochiy & Redman 2011). However in this study, repeatedly heated soybean oil was shown to increase blood pressure in rats. This finding was in accordance with a previous study showing prolonged intake of repeatedly heated oil increased blood pressure (Leong et al. 2008). Few studies have demonstrated the possible links between hypertension with the consumption of polar compounds in the cooking oil (Soriguer et al. 2003) and the increase in the levels of reactive oxygen species (Chan et al. 2006). We believe that the deleterious effect of prolonged intake of 5HSO or 10HSO on blood pressure might be contributed by the increased reactive oxygen species, as reflected by higher level of peroxide value in 5HSO and 10HSO. Although we did not measure the serum thiobarbituric acid reactive substance (TBARS) as one of the oxidative stress markers, our earlier experiment reported that heated soy oil increased lipid oxidation as indicated by a significant increase in TBARS (Adam et al. 2008). This finding suggests that heated soybean oil impairs oxidative status in the rats.

Intake of 5HSO or 10HSO increased the expressions of adhesion molecules VCAM-1 and ICAM-1, which may indicate endothelial activation and inflammatory responses in the rats. Increased presence of reactive oxygen species can overwhelm the intercellular antioxidant defence, leading to inflammation and endothelial injury as described by Williams et al. (1999). The result of our present study was in agreement with Lee et al. (2001) who reported that changes in the oxidative status of endothelial cells are responsible for the expression of adhesion molecules.

Furthermore, we observed significant positive correlations between blood pressure and both VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 expressions. These findings suggest that inflammation might play a role in the elevation of blood pressure following prolonged consumption of repeatedly heated soybean oils in the animals. Supporting our findings, some previous studies also documented the association between hypertension and increased VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 expressions (Parissis et al. 2001; Boulbou et al. 2005). The augmented expression of these inflammatory adhesion molecules on activated endothelial cells mediates the rapid recruitment of leucocytes to the site of endothelial injury.

In present study, we found that the LOX-1 expression was increased in 5HSO- and 10HSO-fed rats. LOX-1 can be up-regulated by oxidative stress (Mehta et al. 2006). We observed significant positive correlations between LOX-1 and the expressions of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1. Inoue et al. (2005) demonstrated that LOX-1 over-expression promoted the expression of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 on the endothelial cells, which further contributing to vascular inflammation. Hence, increased LOX-1 may play a role in inflammation (Cominacini et al. 2000). The significant positive relationship between LOX-1 expression and blood pressure suggests that LOX-1 may as well play a part in the blood pressure raising effect of repeatedly heated soybean oil. This finding was in agreement with the results by Nagase et al. (1997) reporting that LOX-1 expression in the aorta was up-regulated in hypertensive rats, which may be involved in the impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation in these rats.

PGI2 production was decreased in 5HSO and 10HSO groups, which might be attributed to increased oxidative stress. Increased oxidative stress decreases the ability of the aorta to produce PGI2 in rats (Mahfouz & Kummerow 2004), by reducing the activity of PGI2 synthase in aorta (Du et al. 2006). Subsequently, reduced PGI2 caused an increase in blood pressure. In addition, the TXA2 and PGI2 ratio was observed to correlate significantly inversely with the expression of VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and LOX-1. These results suggest that an increase in inflammatory adhesion molecules may reflect endothelial failure in producing PGI2, and subsequently, it would impair the balance between these prostanoids. Supporting our findings, Iliodromitis et al. (2007) reported that a significant reduction in the cell adhesion molecule expressions may indicate a better preservation of endothelial function. Inflammation may contribute to vascular damage. Moreover, the study by Vayssettes-Courchay et al. (2010) also showed that inflammation activated TXA2, causing an imbalance between TXA2 and PGI2.

However in this study, 10HSO decreased TXA2, whilst 5HSO increased it. We postulated that higher reactive oxygen species in 10HSO inhibited TXA2 synthase, whilst lower oxidants in 5HSO stimulated TXA2 formation. TXA2 production was previously found to be stimulated at a low concentration of oxidizing agents, followed by an inhibition at a higher concentration (Hecker et al. 1991; Ambrosio et al. 1994). Although TXA2 concentration was lower in 10HSO group, but we observed 10HSO increased TXA2/PGI2 ratio, which suggests an imbalance between TXA2 and PGI2. It must be kept in mind that the importance of these two vasoactive substances is not about the production of either TXA2 or PGI2, but the balance between them (Smith et al. 1991). Both 5HSO and 10HSO groups showed increased TXA2/PGI2 ratio, which may suggest the vasoconstrictor effect of TXA2 may overpower the vasodilator effect of PGI2, leading to elevated blood pressure. Supporting the findings, our previous experiment demonstrated that intake of repeatedly oils attenuated vascular relaxation but enhanced contraction in rats (Leong et al. 2010).

Our finding suggests that prolonged consumption of repeatedly heated soybean oils causes vascular hypertrophy, as shown by the increased thickness and area of the aortic wall. It is well recognized that increased blood pressure is associated with an altered biochemical environment (Arribas et al. 2006). An imbalance between PGI2 and TXA2 may play a role in inducing hypertrophic remodelling. PGI2 inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation (Kothapalli et al. 2003) and maintains the vascular integrity, conferring cardioprotection. On the contrary, TXA2 promotes proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. The increasing pattern in the nuclei size from the control to the 10HSO group might indicate smooth muscle cell hypertrophy. In addition, increased inflammation may also induce vascular remodelling (Liu et al. 2010). Furthermore, high blood pressure may increase CWT, which is the force that counterbalancing the strain produced by blood pressure on the vessel wall, and further predisposes the vascular wall to damage (Intengan et al. 1999). However, TS, which is the tension per unit of thickness and acts perpendicularly to the wall, did not differ amongst the groups maybe due to the wall thickening. Overall, this vascular remodelling may compromise the compliance of blood vessel in the blood pressure regulation.

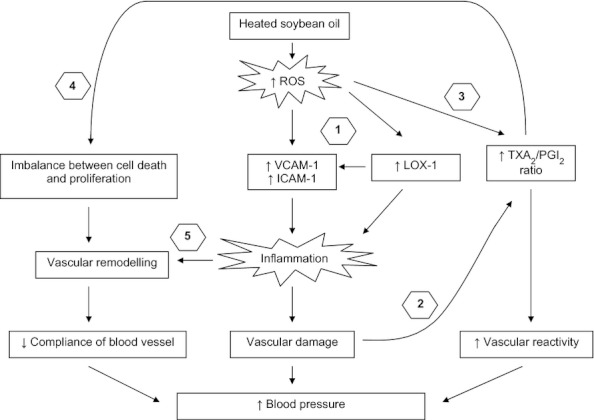

Lastly, our findings suggest that inflammation might play a role in the blood pressure elevation after prolonged intake of repeatedly heated soybean oil. The possible blood pressure raising mechanisms caused by repeatedly heated soybean oil is depicted in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Proposed mechanisms of the blood pressure raising effects after prolonged consumption of repeatedly heated soybean oil in rats. (1) Excessive reactive oxygen species produced during the repeated heating process of soybean oil induces the endothelial VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and LOX-1, which in turn stimulate inflammatory responses, causing vascular damage. (2) Inflammation impairs endothelial function in PGI2 formation but induces TXA2 production. (3) Reactive oxygen species also alters the arachidonic acid pathway, in which by favouring the TXA2 pathway over the PGI2 pathway, resulting in an imbalance between TXA2 and PGI2. Subsequently, this situation enhances vasoconstriction and attenuates vasorelaxation of blood vessel. (4) An altered prostanoids environment causes an imbalance between the cell death and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells, leading to adverse vascular remodelling. Changes in vascular architecture decrease the compliance of blood vessel in regulating blood pressure. (5) Inflammation also plays a role in vascular remodelling. All these circumstances lead to an increase in blood pressure.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that FSO does not cause deleterious effects on blood pressure in rats. Prolonged consumption of repeatedly heated soybean oil, however, increases blood pressure. The blood pressure raising effect of the repeatedly heated soybean oil might be mediated by the increased inflammation, leading to an altered prostanoid production and adverse vascular remodelling.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by UKM Medical Faculty Research Grant FF-161-2010 and UKM-GUP-SK-08-21-299. The authors wish to thank Madam Azizah Osman and Madam Sinar Suriya Muhamad of the Department of Pharmacology; as well as Prof. Dr. Siti Aishah Md Ali of the Histopathology Unit, Department of Pathology, Univerisit Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre, Cheras, for their kind assistance.

Funding source

UKM Medical Faculty Research Grant FF-161-2010 and UKM-GUP-SK-08-21-299.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Adam SK, Das S, Soelaiman IN, Nor Aini U, Jaarin K. Consumption of repeatedly heated soy oil increases the serum parameters related to arthrosclerosis in ovariectomized rats. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2008;215:219–226. doi: 10.1620/tjem.215.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso Á, Ruiz-Gutierrez V, Martínez-González MÁ. Monounsaturated fatty acids, olive oil and blood pressure: epidemiological, clinical and experimental evidence. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9:251–257. doi: 10.1079/phn2005836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosio G, Golino P, Pascucci I, et al. Modulation of platelet function by reactive oxygen metabolites. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;267:H308–H318. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.1.H308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arribas SM, Hinek A, González MC. Elastic fibres and vascular structure in hypertension. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006;111:771–791. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal G, Zhou W, Barlow PJ, Lo HL, Neo FL. Performance of palm olein in repeated deep frying and controlled heating processes. Food Chem. 2010;121:338–347. [Google Scholar]

- Boskou G, Salta FN, Chiou A, Troullidou E, Andrikopoulos NK. Content of trans,trans-2,4-decadienal in deep-fried and pan-fried potatoes. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2006;108:109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Boueiz A, Hassoun PM. Regulation of endothelial barrier function by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Microvasc. Res. 2009;77:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulbou MS, Koukoulis GN, Makri ED, Petinaki EA, Gourgoulianis KI, Germenis AE. Circulating adhesion molecules levels in type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Int. J. Cardiol. 2005;98:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burenjarga M, Totani N. Effects of thermally processed oil on weight loss in rats. J. Oleo Sci. 2008;57:463–470. doi: 10.5650/jos.57.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SHH, Tai MH, Li CY, Chan JYH. Reduction in molecular synthesis or enzyme activity of superoxide dismutases and catalase contributes to oxidative stress and neurogenic hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006;40:2028–2039. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Masaki T, Sawamura T. LOX-1, the receptor for oxidized low-density lipoprotein identified from endothelial cells: implications in endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002;95:89–100. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00236-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cominacini L, Pasini AF, Garbin U. Oxidized low density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) binding to ox-LDL receptor-1 in endothelial cells induces the activation of NF-kappaB through an increased production of intracellular reactive oxygen species. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:12633–12638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.17.12633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X, Edelstein D, Obici S, Higham N, Zou MH, Brownlee M. Insulin resistance reduces arterial prostacyclin synthase and eNOS activities by increasing endothelial fatty acid oxidation. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:1071–1080. doi: 10.1172/JCI23354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkkilä A, de Mello VDF, Risérus U, Laaksonen DE. Dietary fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: an epidemiological approach. Prog. Lipid Res. 2008;47:172–187. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes-Santos C, Mendonça LDS, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA. Favorable cardiac and aortic remodeling in olmesartan-treated spontaneously hypertensive rats. Heart Vessels. 2009;24:219–227. doi: 10.1007/s00380-008-1104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanem FA, Movahed A. Inflammation in high blood pressure: a clinician perspective. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 2007;1:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh N, Wada S. The importance of peroxide value in assessing food quality and food safety. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2006;83:473–474. [Google Scholar]

- Hecker G, Utz J, Kupferschmidt RJ, Ullrich V. Low levels of hydrogen peroxide enhance platelet aggregation by cyclooxygenase activation. Eicosanoids. 1991;4:107–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitson TD, Wigg B, Becker GJ. Tissue preparation for histochemistry: fixation, embedding, and antigen retrieval for light microscopy. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;611:3–18. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-345-9_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliodromitis EK, Andreadou I, Markantonis-Kyroudis S, et al. The effects of tirofiban on peripheral markers of oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Thromb. Res. 2007;119:167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Arai Y, Kurihara H, Kita T, Sawamura T. Overexpression of lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 induces intramyocardial vasculopathy in apolipoprotein E-null mice. Circ. Res. 2005;97:176–184. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000174286.73200.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intengan HD, Thibault G, Li JS, Schiffrin EL. Resistance artery mechanics, structure, and extracellular components in spontaneously hypertensive rats: effects of angiotensin receptor antagonism and converting enzyme inhibition. Circulation. 1999;100:2267–2275. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.22.2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer AS, Ahmed MI, Filippatos GS, et al. Uncontrolled hypertension and increased risk for incident heart failure in older adults with hypertension: findings from a propensity-matched prospective population study. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 2010;4:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juárez MD, Osawa CC, Acuña ME, Sammán N, Gonçalves LAG. Degradation in soybean oil, sunflower oil and partially hydrogenated fats after food frying, monitored by conventional and unconventional methods. Food Control. 2011;22:1920–1927. [Google Scholar]

- Kim YM, Kim MY, Kim HJ, et al. Compound C independent of AMPK inhibits ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression in inflammatory stimulants-activated endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kothapalli D, Stewart SA, Smyth EM, Azonobi I, Puré E, Assoian RK. Prostacylin receptor activation inhibits proliferation of aortic smooth muscle cells by regulating cAMP response element-binding protein- and pocket protein-dependent cyclin A gene expression. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003;64:249–258. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen D, Quek SY, Eyres L. Evaluating instrumental colour and texture of thermally treated New Zealand King Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) and their relation to sensory properties. LWT– Food Sci. Technol. 2011;44:1814–1820. [Google Scholar]

- Lee YW, Kühn H, Hennig B, Neish AS, Toborek M. IL-4-induced oxidative stress upregulates VCAM-1 gene expression in human endothelial cells. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2001;33:83–94. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong XF, Aishah A, Nor Aini U, Das S, Jaarin K. Heated palm oil causes rise in blood pressure and cardiac changes in heart muscle in experimental rats. Arch. Med. Res. 2008;39:567–572. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong XF, Mustafa MR, Das S, Jaarin K. Association of elevated blood pressure and impaired vasorelaxation in experimental Sprague-Dawley rats fed with heated vegetable oil. Lipids Health Dis. 2010;9:66. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-9-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BI, Benessiano J, Henrion D, et al. Chronic blockade of AT2-subtype receptors prevents the effect of angiotensin II on the rat vascular structure. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;98:418–425. doi: 10.1172/JCI118807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Zhang C, Zhao YX. Gax gene transfer inhibits vascular remodeling induced by adventitial inflammation in rabbits. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212:398–405. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahfouz MM, Kummerow FA. Vitamin C or vitamin B6 supplementation prevent the oxidative stress and decrease of prostacyclin generation in homocysteinemic rats. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2004;36:1919–1932. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA, Fernandes-Santos C, Aguila MB. Image analysis and quantitative morphology. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;611:211–225. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-345-9_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmesat S, Velasco J, Dobarganes MC. Quantitative determination of epoxy acids, keto acids and hydroxy acids formed in fats and oils at frying temperatures. J. Chromatogr. A. 2008;1211:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.09.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta JL, Chen J, Hermonat PL, Romeo F, Novelli G. Lectin-like, oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 (LOX-1): a critical player in the development of atherosclerosis and related disorders. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006;69:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes-Teixeira JDA, Félix A, Fernandes-Santos C, Moura AS, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA, de Carvalho JJ. Exercise training enhances elastin, fibrillin and nitric oxide in the aorta wall of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2010;89:351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzaffar S, Shukla N, Massey Y, Angelini GD, Jeremy JY. NADPH oxidase 1 mediates upregulation of thromboxane A2 synthase in human vascular smooth muscle cells: inhibition with iloprost. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011;658:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadtochiy SM, Redman EK. Mediterranean diet and cardioprotection: the role of nitrite, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and polyphenols. Nutrition. 2011;27:733–744. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase M, Hirose S, Sawamura T, Masaki T, Fujita T. Enhanced expression of endothelial oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor (LOX-1) in hypertensive rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;237:496–498. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura S, Kakino A, Sato Y, et al. LOX-1 the multifunctional receptor underlying cardiovascular dysfunction. Circ. J. 2009;73:1993–1999. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owu DU, Osim EE, Ebong PE. Serum liver enzymes profile of Wistar rats following chronic consumption of fresh or oxidized palm oil diets. Acta Trop. 1998;69:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(97)00115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parissis JT, Venetsanou KF, Mentzikof DG, et al. Plasma levels of soluble cellular adhesion molecules in patients with arterial hypertension. Correlations with plasma endothelin-1. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2001;12:350–356. doi: 10.1016/s0953-6205(01)00125-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radaelli A, Cazzaniga M, Viola A, et al. Enhanced baroreceptor control of the cardiovascular system by polyunsaturated fatty acids in heart failure patients. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006;48:1600–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro RF, Jr, Fernandes AA, Meira EF, et al. Soybean oil increases SERCA2a expression and left ventricular contractility in rats without change in arterial blood pressure. Lipids Health Dis. 2010;9:53. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-9-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero A, Bastida S, Sánchez-Muniz FJ. Cyclic fatty acid monomer formation in domestic frying of frozen foods in sunflower oil and high oleic acid sunflower oil without oil replenishment. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2006;44:1674–1681. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi M, Alamprese C, Ratti S. Tocopherols and tocotrienols as free radical-scavengers in refined vegetable oils and their stability during deep-fat frying. Food Chem. 2007;102:812–817. [Google Scholar]

- Smith WL, Marnett LJ, De Witt DL. Prostaglandin and thromboxane biosynthesis. Pharmacol. Ther. 1991;49:153–179. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(91)90054-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriguer F, Rojo-Martínez G, Dobarganes MC, et al. Hypertension is related to the degradation of dietary frying oils. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003;78:1092–1097. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.6.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture. Oilseeds: world markets and trade. Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vayssettes-Courchay C, Ragonnet C, Camenen G. Role of thromboxane TP and angiotensin AT1 receptors in lipopolysaccharide-induced arterial dysfunction in the rabbit: an in vivo study. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010;635:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MJA, Sutherland WHF, McCormick MP, de Jong SA, Walker RJ, Wilkins GT. Impaired endothelial function following a meal rich in used cooking fat. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1999;33:1050–1055. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00681-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Global Health Risks: Mortality and Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risks. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Omata K, Abe F, Ito S, Abe K. Changes in prostacyclin, thromboxane A2 and F2-isoprostanes, and influence of eicosapentaenoic acid and antiplatelet agents in patients with hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Immunopharmacology. 1999;44:193–198. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(99)00137-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamsaengsung R, Moreira RG. Modeling the transport phenomena and structural changes during deep fat frying: part II: model solution & validation. J. Food Engineering. 2002;53:11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zaina S, Pettersson L. Normal size of the lumen of the aorta in dwarf mice lacking IGF-II. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2001;11:298–302. doi: 10.1054/ghir.2001.0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]