Abstract

We report that eight patients from France, Italy, and Thailand had serological evidence of Rickettsia helvetica infection. The infection presented as a mild disease in the warm season and was associated with fever, headache, and myalgia but not with a cutaneous rash. R. helvetica should be suspected in patients with unexplained fever, especially following a bite from an Ixodes sp. tick.

Rickettsia helvetica, a rickettsia from the spotted fever group, has been detected in Ixodes sp. ticks in Switzerland, Sweden, France, Italy, Portugal, Slovenia, and Japan (1, 2, 4-6, 18). To date, the pathogenic role of this rickettsia is unclear but has been suspected in acute perimyocarditis (12), unexplained febrile illness (7), sarcoidosis (13), and fever following an Ixodes holocyclus bite (8).

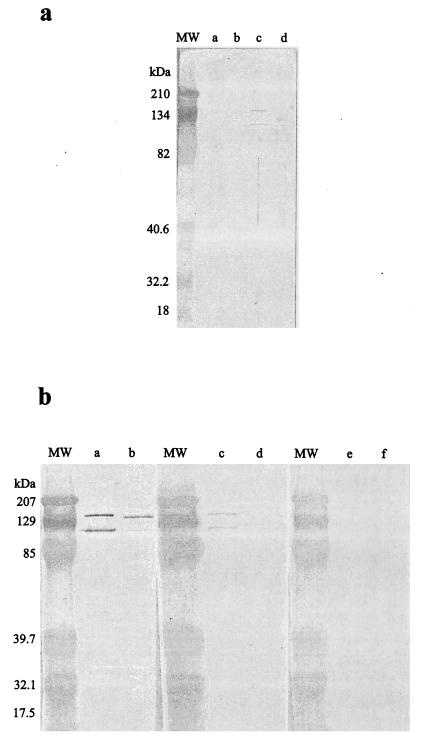

Using the microimmunofluorescence assay (9) and Western blotting performed on early-phase serum (21), we searched the serum from 37,945 patients with a suspected rickettsial infection for antibodies to R. conorii, R. slovaca, R. massiliae, R. mongolotimonae, R. helvetica, R. felis, R. typhi, Borrelia burgdorferi, and Anaplasma phagocytophilum for European patients and to R. helvetica, R. felis, R. honei, R. japonica, R. typhi, Orientia tsutsugamushi, and Leptospira interrogans serotype Icterohaemorrhagiae for Asian patients. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. We used microimmunofluorescence assay titers of 1:64 for immunoglobulin G (IgG) and 1:32 for IgM as cutoff values for rickettsial infections. We also searched for antibodies to the tick-borne encephalitis virus (IgM TBE ELISA kit; IBL Laboratories, Hamburg, Germany) in the sera of European patients. When cross-reacting antibodies above 1:64 prevented the identification of the infecting agent, we performed cross-adsorption by using either R. helvetica and R. conorii antigens for European patients or R. helvetica and R. honei antigens for Asian patients, followed by Western blotting, as previously described (10). To detect a specific anti-R. helvetica response in eight patients, i.e., three Italian, two French, and three Thai patients, we used the following diagnostic criteria: (i) a Western blot showing an antibody response only to R. helvetica proteins (21) and/or (ii) the presence of homologous antibodies directed against R. helvetica following cross-adsorption (10). For these patients, serum was the only type of specimen available. The case of one of the two French patients has previously been reported (7). Among the five European patients, patients 1 to 3 (Table 1) exhibited IgM titers of >1:32 to R. helvetica in their early-phase serum; patient 4 developed an IgG titer of 1:128 and an IgM titer of 1:64 in his convalescent-phase serum; and patient 5, for whom only an early-phase sample was available, was seronegative. The Western blot demonstrated the presence of antibodies only to R. helvetica in patients 1 and 5 (Fig. 1a), and cross-adsorption revealed the presence of homologous antibodies to R. helvetica in patients 2 to 4 (Fig. 1b). All other serological tests were negative for all five patients. Among the Thai patients, patients 7 and 8 exhibited IgM titers of >1:32 to R. helvetica in the early-phase serum, and patient 6 had an IgG titer of 1:128. The Western blot demonstrated the presence of antibodies directed only against R. helvetica in patient 7, and cross-adsorption revealed the presence of homologous antibodies to R. helvetica in patients 6 and 8. Serological tests for L. interrogans were negative for all Thai patients.

TABLE 1.

Epidemiological and clinical findings for 13 patients with R. helvetica infection

| Patient | Ageb | Sex | Geographic area | Month of onset | Fevera | Head- achea | Myal- giaa | Arthral- giaa | Conjunc- tivitisa | Report of tick bite (location)a | Inoculation eschar (location)a | Cuta- neous rasha | Treatmenta | Recov- erya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 70 | M | Northern Italy | May | + | + | − | + | − | + (right thigh) | + (right thigh) | − | No treatment | − |

| 2 | 58 | M | Northern Italy | May | + | + | + | + | − | + (left buttock) | − | − | No treatment | − |

| 3 | 50 | F | Northern Italy | May | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | No treatment | − |

| 4 | 37 | M | Northeastern France | August | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | No treatment | − |

| 5 | 63 | F | Northeastern France | June | + | + | − | + | − | + (leg) | − | − | No treatment | − |

| 6 | 27 | M | Northeastern Thailand | January | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | Doxycycline | − |

| 7 | 43 | M | Northeastern Thailand | December | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | Cefotaxime | − |

| 8 | 57 | M | Northeastern Thailand | October | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | Doxycycline | − |

| Total (%) | 6M, 2F | 8 (100) | 8 (100) | 6 (75) | 5 (62) | 2 (25) | 4 (50) | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 8 (100) |

+, positive criterion; −, negative criterion.

The mean age of the patients was 50.6 ± 14.2 years.

FIG.1.

(a) Western immunoblot for patient 1 showing an antibody response directed against outer membrane proteins of R. helvetica only. Lane a, R. conorii; lane b, R. slovaca; lane c, R. helvetica; lane d, R. mongolotimonae. (b) Western immunoblot for patient 11 before and after cross-adsorption with R. helvetica or R. honei. Lanes a, c, and e, R. helvetica antigen; lanes b, d, and f, R. honei antigen. Lanes a and b, untreated serum; lanes c and d, serum adsorbed with R. honei; lanes e and f, serum adsorbed with R. helvetica. MW, molecular mass; kDa, kilodalton.

The median age of the patients was 53 years (range, 27 to 70 years) (Table 1). Three European patients were male, and four patients reported suffering a tick bite in a forest during the period from May to August. Clinical symptoms included fever, headache, and arthralgia in all patients, myalgia in four, and an inoculation eschar in one but no cutaneous rash. An elevated leukocytosis was found in one case, thrombocytopenia was found in two cases, and elevated transaminase levels were found in three cases. None of these patients received any antibiotic, and all recovered without any sequellae. All three Thai patients were male and worked as rice farmers, and none reported any tick bite. Infection occurred from October to January. All three patients suffered from fever and headache, and two suffered from unilateral conjunctivitis but did not suffer from inoculation eschar or rash. An elevated leukocyte count was noted in two patients, and thrombocytopenia and elevated transaminase levels were noted in one. Other possible diagnoses of fever in the patients from Thailand, including malaria, viral hepatitis, and typhoid fever, had previously been eliminated. The patients received either 10 MU of penicillin G, 3 g of cefotaxime, or 200 mg of doxycycline/day and recovered without sequellae.

Overall, in the warm season eight adult patients developed a mild, aneruptive febrile illness associated with headache and myalgia and, in only one case, an inoculation eschar. The lack of one or several of the classical symptoms of rickettsiosis does not eliminate this diagnosis. For example, the eschar is rare in Israeli spotted fever and Astrakhan fever and exceptional in Rocky Mountain spotted fever (19). A rash is also rare in R. slovaca infections (17) and present in only 50% of cases of R. africae infections (16). Elevated liver enzymes, or thrombocytopenia, common in rickettsioses, was observed in 75% of our patients. Determination of the causative role of R. helvetica in the illness in these patients relied on an array of evidence. (i) We tested our patients' sera for rickettsial species known to be endemic in their own areas and found antibodies specifically directed against R. helvetica. Although serological cross-reactions were observed among tested antigens (9), Western blots showing antibodies to R. helvetica only or cross-adsorption to remove heterologous antibodies reflected specific antibody responses, as previously demonstrated for R. slovaca, R. africae, R. prowazekii, and R. typhi infections (10, 16, 17) (Fig. 1). (ii) The causative role of R. helvetica was considered, as it is the main rickettsia found in Ixodes sp. in Europe, occurring in from 2 to 36.8% of I. ricinus ticks (3, 5, 11, 14, 14, 18). In Thailand, its presence is as yet unknown in Ixodes sp. ticks, although human cases of R. helvetica infection have been highly suspected in that country (15). (iii) The season of occurrence and interviews with patients suggested that the infections were caused by Ixodes sp. ticks. All patients were diagnosed in a warm season, which is consistent with the optimal development conditions of immature Ixodes sp. ticks. Although four patients from Europe reported a tick bite, the tick species was not identified. However, in Italy I. ricinus represents more than 90% of all ticks collected from humans during the spring (18). In Thailand, Ixodes sp. ticks are endemic, including I. ovatus (20), which is known to harbor R. helvetica in Japan (6). (iv) These patients tested negative against other pathogens endemic in these areas.

In our series, R. helvetica infection presented as a flu-like, self-limiting febrile illness without any sequellae. Further studies to confirm the causative role of R. helvetica in acute febrile illness should be conducted by culture or PCR amplification from clinical specimens.

Footnotes

In memory of Giuseppe Caruso (1938-2003), a famous tick hunter, dedicated medical doctor, and friend.

REFERENCES

- 1.Avsic-Zupanc, T., K. Prosenc, and M. Petrovec. 1999. Spotted fever group rickettsiae in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Slovenia, p. 92. In D. Raoult and P. Brouqui (ed.), Abstracts from the 1999 Euwog-ASR joint meeting. Elsevier, Marseille, France.

- 2.Bacellar, F. 1999. Ticks and spotted fever rickettsiae in Portugal, p. 423-427. In D. Raoult and P. Brouqui (ed.), Rickettsiae and rickettsial diseases at the turn of the third millenium. Elsevier, Paris, France.

- 3.Beati, L., P. F. Humair, A. Aeschlimann, and D. Raoult. 1994. Identification of spotted fever group rickettsiae isolated from Dermacentor marginatus and Ixodes ricinus ticks collected in Switzerland. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 51:138-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beninati, T., N. Lo, H. Noda, F. Esposito, A. Rizzoli, G. Favia, and C. Genchi. 2002. First detection of spotted fever group rickettsiae in Ixodes ricinus from Italy. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:983-986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burgdorfer, W., A. Aeschlimann, O. Peter, S. F. Hayes, and R. N. Philip. 1979. Ixodes ricinus: vector of a hitherto undescribed spotted fever group agent in Switzerland. Acta Trop. 36:357-367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fournier, P. E., H. Fujita, N. Takada, and D. Raoult. 2002. Genetic identification of rickettsiae isolated from ticks in Japan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2176-2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fournier, P. E., F. Gunnenberger, B. Jaulhac, G. Gastinger, and D. Raoult. 2000. Evidence of Rickettsia helvetica infection in humans, Eastern France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 6:389-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inokuma, H., H. Takahata, P. E. Fournier, P. Brouqui, D. Raoult, M. Okuda, T. Onishi, K. Nishioka, and M. Tsukahara. 2003. Tick paralysis by Ixodes holocyclus in a Japanese traveler returning from Australia associated with Rickettsia helvetica infection. J. Travel Med. 10:61-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.La Scola, B., and D. Raoult. 1997. Laboratory diagnosis of rickettsioses: current approaches to the diagnosis of old and new rickettsial diseases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2715-2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.La Scola, B., L. Rydkina, J. B. Ndihokubwayo, S. Vene, and D. Raoult. 2000. Serological differentiation of murine typhus and epidemic typhus using cross-adsorption and Western blotting. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 7:612-616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nilsson, K., O. Lindquist, A. Liu, T. G. T. Jaenson, G. Friman, and C. Pahlson. 1999. Rickettsia helvetica in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Sweden. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:400-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nilsson, K., O. Lindquist, and C. Pahlson. 1999. Association of Rickettsia helvetica with chronic perimyocarditis in sudden cardiac death. Lancet 354:1169-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nilsson, K., C. Pahlson, A. Lukinius, L. Eriksson, L. Nilsson, and O. Lindquist. 2002. Presence of Rickettsia helvetica in granulomatous tissue from patients with sarcoidosis. J. Infect. Dis. 185:1128-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parola, P., L. Beati, M. Cambon, and D. Raoult. 1998. First isolation of Rickettsia helvetica from Ixodes ricinus ticks in France. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 17:95-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parola, P., R. S. Miller, P. McDaniel, S. R. Telford III, J. M. Rolain, C. Wongsrichanalai, and D. Raoult. 2003. Emerging rickettsioses of the Thai-Myanmar border. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:592-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raoult, D., P. E. Fournier, F. Fenollar, M. Jensenius, T. Prioe, J. J. de Pina, G. Caruso, N. Jones, H. Laferl, J. E. Rosenblatt, and T. J. Marrie. 2001. Rickettsia africae, a tick-borne pathogen in travelers to sub-Saharan Africa. N. Engl. J. Med. 344:1504-1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raoult, D., A. Lakos, F. Fenollar, J. Beytout, P. Brouqui, and P. E. Fournier. 2002. Spotless rickettsiosis caused by Rickettsia slovaca and associated with Dermacentor ticks. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:1331-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanogo, Y. O., P. Parola, S. Shpynov, G. Caruso, J. L. Camicas, P. Brouqui, and D. Raoult. 2003. Genetic diversity of bacterial agents detected in ticks removed from asymptomatic patients in northeastern Italy. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 990:182-190. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Sexton, D. J., and K. S. Kaye. 2002. Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Med. Clin. North Am. 86:351-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanskul, P., H. E. Stark, and I. Inlao. 1983. A checklist of ticks of Thailand (Acari: Metastigmata: Ixodoidea). J. Med. Entomol. 20:330-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teysseire, N., and D. Raoult. 1992. Comparison of Western immunoblotting and microimmunofluoresence for diagnosis of Mediterranean spotted fever. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:455-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]