Abstract

Eukaryotic protein kinases (EPK)feature two co-evolved structural segments, the Activation segment which starts with the Asp-Phe-Gly (DFG) and ends with the Ala-Pro-Glu (APE) motifs, and the helical GHI-subdomain that comprises αG-αH-αI helices. Eukaryotic-like kinases have a much shorter Activation segment and lack the GHI-subdomain. They thus lack the conserved salt bridge interaction between the APE Glu and an Arg from the GHI-subdomain, a hallmark signature of EPKs. Although the conservation of this salt bridge in EPKs is well known and its implication in diseases has been illustrated by polymorphism analysis, its function has not been carefully studied. In this work, we use murine cAMP dependent protein kinase (PKA) as the model enzyme (Glu208 and Arg280) to examine the role of these two residues. We showed that Ala replacement of either residue caused a 40–120 fold decrease in catalytic efficiency of the enzyme due to an increase in Km(ATP) and a decrease in kcat. Crystal structures, as well as solution studies, also demonstratethat this ion pair contributes to the hydrophobic network and stability of the enzyme. We show that mutation of either Glu or Arg to Ala renders bothmutant proteins less effective substrates for upstream kinase phosphoinositide dependent kinase 1. We propose that the Glu208-Arg280 pair serves as a center hub of connectivity between these two structurally conserved elements in EPKs. Mutations of either residue disrupt communication not only between the two segments but also within the rest of the molecule leading to altered catalytic activity and enzyme regulation.

Keywords: cAMP dependent protein kinase, catalysis, ion-pair, crystal structure, hydrogen-deuterium exchange, long range regulation, PDK1

INTRODUCTION

Protein kinases are a large family of enzymes that perform posttranslational phosphorylation of proteins and thus regulate a broad range of cellular events. All protein kinases share a conserved kinase domain with significant sequence and structure similarities. This domain has a distinctive bilobal tertiary fold with a smaller N-terminal lobe (N-lobe), that contains mostly β-strands, and a larger C-terminal lobe (C-lobe), which is predominantly α-helical. ATP binds in the deep cleft between these lobes and the substrate binds mostly to the C-lobe. The latter includes a large regulatory Activation segment that usually contains a phosphorylation site allowing the protein kinases to be regulated by phosphorylation. This regulatory mechanism, however, is specific only for eukaryote protein kinases (EPKs). Eukaryote-like kinases (ELKs), that are abundant in bacteria and archaea, instead of the Activation segment have a short loop and are not regulated by phosphorylation 1 (Figure 1A). Besides the absence of the Activation segment, the C-lobe of ELKs is much larger and contains multiple α-helices that are not conserved in different ELKs. In contrast to ELKs the very C-terminus of EPKs contains only three short α-helices: αG, αH and αI. As was pointed out previously2, this helical motif, called GHI-subdomain, has coevolved in EPKs together with the Activation segment as a part of the EPK regulatory mechanism.

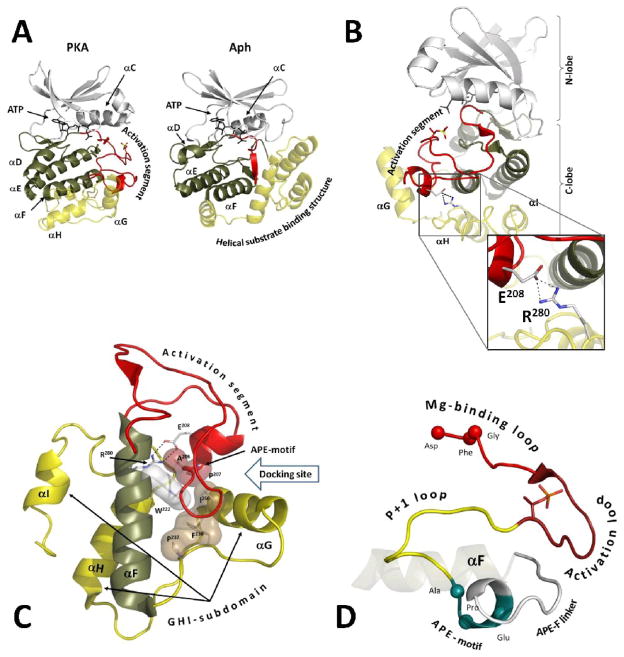

Figure 1. The Activation segment and the GHI subdomain in ELKs.

A) Comparison of eukaryotic protein kinase A (PKA) and eukaryote-like kinase Aminoglycoside phosphotransferase (Aph). The N-lobe is colored white. The three helixes from the C-lobe that are common for both EPKs and ELKs are colored tan. Other helixes in the C-lobe are semitransparent and colored yellow. The Activation segment in EPKs and the corresponding part of the C-lobe in ELKs are shown as red ribbon. B) The Glu208-Arg280 salt bridge connects the Activation segment (red ribbon) and the αH-αI loopin the GHI subdomain (yellow helices). C)Conserved hydrophobic interactions dock the Activation segment and the GHI-subdomain to the αF-helix (colored tan), the central structural element of the C-lobe. Trp222 from the αF-helix is shown as white surface. Hydrophobic residues from the Activation segment are shown as red surface. Hydrophobic residues from the GHI-subdomain are shown as sand surface. D) Extended Activation segment. The Mg-binding loop with the DFG-motif is colored bright red. The Activation loop with the primary phosphorylation site is colored dark red. The P+1 loop is colored yellow. The APE-motif is colored teal. The additional APE-F linker is shown as white ribbon.

The Activation segments of different EPKs are very well studied. They contain two highly conserved sequence motifs: Asp-Phe-Gly (DFG) at the N-terminus and Ala-Pro-Glu (APE) at the C-terminus. The DFG-motif is a part of the magnesium positioning loop, allowing the DFG-aspartate to coordinate magnesium ions in the active site. The APE-motif is a central point of interaction between the Activation segment and the GHI-subdomain. The APE-glutamate binds to another conserved residue from the GHI-subdomain: Arg280, which is located in the loop between the αH and αI helices (αH–αIloop). This loop is also a docking site for regulatory proteins 3–5 and substrates6. Although conservation of the Glu208-Arg280 salt bridge in EPKs is well-recognized, little is known about rationale or function of such conservation. Nevertheless, bioinformatic analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in EPKs demonstrated that multiple diseases are correlated with mutations of both Glu208 and Arg280 7.

To elucidate the structural and biochemical role of the Glu208-Arg280 salt bridge we studied Glu208Ala and Arg280Ala mutants of cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA). PKA is the best studied protein kinase in terms of structure and function and has served as a model system and paradigm for the whole EPK family8–10. Here we present crystal structures of these mutants, their kinetic analysis and dynamic properties through hydrogen/deuterium (H/D) exchange studies. We discovered that mutation of either residue causes over a 10-fold decrease in kcat, and a 4–15 fold increase in Km(ATP) leading to a 40–120 fold decrease in catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) and destabilizes the entire molecule. Furthermore, destabilization of the kinase after Glu208Ala and Arg280Ala mutations impaired recognition of PKA by the upstream kinase phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1). Significantly, and unrecognized previously, we found that the aliphatic part of Glu208 and Arg280 side chains contributed to the continuity of the hydrophobic network in the C-lobe. Our results suggest that the conserve Glu-Argpair play a critical role bridging the Activation segment and the GHI-subdomain, the two co-evolved signature motifs of EPKs. We demonstrate that this connection between the two motifs in EPKs is critical for protein kinase function and mutations at their interface can cause global destabilization of the molecule.

RESULTS

Decreased catalytic efficiency of the enzyme by Ala-replacement of Arg280 or Glu208

To understand the function of the conserved Arg280-Glu208 interaction, we mutated each of the residues to Ala in the catalytic subunit (C) of PKA, and examined the kinetic properties of both mutants (referred to as CE208A and CR280A for mutant proteins). For the kinetic assay, besides the conventional substrate peptide, Kemptide, we also used two established protein substrates for PKA, the type 1 Ser/Thr phosphatase (PP1) inhibitors DARPP-32 and PP1_I-111,12. As shown in Table 1, when using Kemptide as a substrate, the wild type enzyme had a Km for Kemptide of 26 μM, Km for ATP of 23 μM, and kcat of 23/sec; these values were similar to previously published data13. When using protein substrates, the wild type enzyme showed marginal kinetic variations in the 2-fold range in kcat and Km, comparing with the peptide substrate. Significantly, whether using peptide or protein substrate, both CE208A and CR280A mutants exhibited similar Km for substrates but ~ 10-fold decrease in kcat, when compared with the wild type enzyme with corresponding substrates. Furthermore, CE208A showed a 13-fold increase in Km for ATP (309 μM), whereas CR280A had a modest 3.7-fold increase(85 μM).As a result, catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of CE208A and CR280A decreased by over 100-fold and 40-fold, respectively, as compared to the wild type enzyme (Table 1).

Table 1.

Enzyme Kinetics of CE208A and CR280A in comparison with the wild type enzyme. Kinetic assay was carried out as described in “Materials and Methods.” Data shown was analyzed from 3–5 replicated experiments. wt-C refers to the wild type C-subunit. Sequence alignment of PKA recognition site in DARP32, PP1_I-1 with Kemptide is shown below. The number indicates the residue numbering for the protein. Phosphorylation consensus of PKA substrate is: RRxS/TΦ (Φ represents a hydrophobic residue)

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| enzyme substrate | wt-C | CR280A | CE208A | ||

| Kemptide | Km(μM) | 26±3 | 31±3* | 30±3 | 10±2 |

| kcat(s−1) | 24±1 | 33.1±3* | 2.4±0.1 | 2.9±0.3 | |

| Km(ATP) | 23±5 | 21.2±4* | 85±13 | 309±61 | |

| kcat/Km(ATP)(μM−1s−1) | 1.0 | 1.07* | 0.028 | 0.009 | |

|

| |||||

| DARPP-32 | Km(μM) | 13±2 | 16.1±0.7 | 10.4±0.7 | |

| kcat(s−1) | 48±3 | 4.4±0.9 | 7±2 | ||

| kcat/Km(ATP)(μM−1s−1) | 2.1 | 0.05 | 0.022 | ||

|

| |||||

| PP1_I-1 | Km(μM) | 9±2 | 13±3 | 6±2 | |

| kcat(s−1) | 8.7±0.7 | 1.0±0.1 | 0.9±0.1 | ||

| kcat/Km(ATP)(μM−1s−1) | 0.378 | 0.011 | 0.003 | ||

- (ref. 13)

Crystal structure of CR280A and CE208A

To capture any possible structural changes caused by the mutations and to understand the molecular basis for how the mutations, especially the distal Arg280Ala mutation, affect kinetics, we crystallized both CE208A and CR280A. For both mutants, we were only able to get crystals under the condition where both MgATP and inhibitory peptide IP20 were present. The ternary complexes were thus solved with a resolution of 1.9Å and 1.7Å for CE208A and CR280A, respectively (Table 2). Although overall structures of the mutants were very similar to that of the ternary structure of wild type C-subunit complexed with MgATP and IP20 (PDB ID 1ATP)14, specific localized differences were observed. For both mutants, no significant structural differences were observed for the Activation segments or the three helices in the GHI subdomain. However, for CR280A, the loop connecting the αH and αI helices, also where R280A resides, was disordered.

Table 2.

Data Collection and Refinement Statistics.

| CR280A | CE208A | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Data collection | ||

|

| ||

| Space group | P212121 | P21 |

|

| ||

| Cell dimensions (Å) | ||

| a | 57.8 | 48.4 |

| b | 80.1 | 79.6 |

| c | 97.7 | 60.8 |

| β (°) | 113.3 | |

|

| ||

| No. of molecule per asymmetrical unit | 1 | 1 |

|

| ||

| Resolution (Å) | 1.7 | 1.9 |

|

| ||

| Rmerge | 0.080 (0.42) | 0.051 (0.44) |

|

| ||

| Completeness (%) | 97.8 (82.0) | 88.8 (65.5) |

|

| ||

| I/sigma | 21.2 (2.4) | 17.0 (2.2) |

|

| ||

| No. reflections | 48566 | 32026 |

|

| ||

| Refinement | ||

|

| ||

| Resolution (Å) | 50.0-1.7 | 50.0-1.9 |

|

| ||

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 17.6/19.4 | 19.5/22.8 |

|

| ||

| No. of protein residues | 350 | 350 |

|

| ||

| No. of ligand/ion | 3 | 3 |

|

| ||

| No. of water | 371 | 282 |

|

| ||

| R.m.s. deviations | ||

|

| ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.007 | 0.008 |

|

| ||

| Bond angles (°) | 1.3 | 1.3 |

|

| ||

| Ramachandran angles | ||

|

| ||

| most favored (%) | 91.7 | 90.7 |

|

| ||

| disallowed (%) | none | none |

Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell: (1.71–1.77 Å) for CR280A; (1.92–1.99 Å) for CE208A

Destabilized αH-αI loop in CR280A

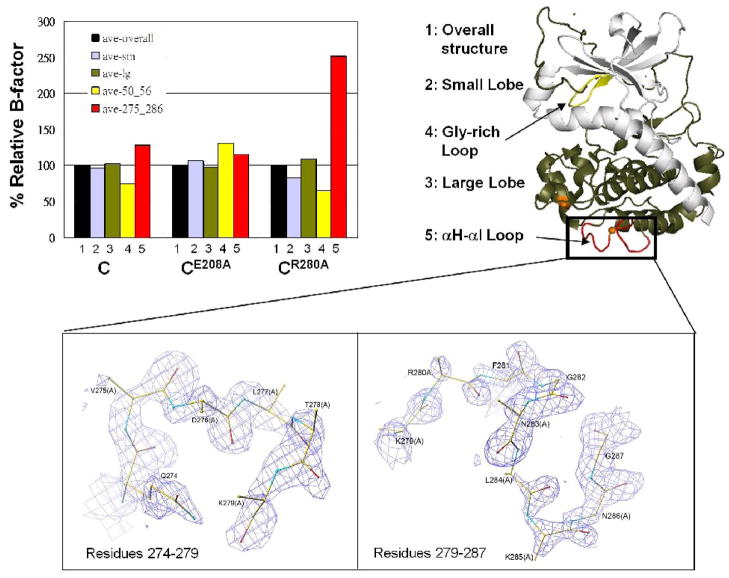

Compared to the structure of the wild type C-subunit or CE208A, the αH-αI loop region in CR280A exhibited significantly increased flexibility. Residues around Arg/Ala280 were disordered. Side chains of a twelve-residue stretch (275VDLTKR/AFGNLKN286) in the loop were not traceable in CR280A (Figure 2, bottom), except for Phe281 with a weaker density for its aromatic side chain. Correspondingly, the temperature B-factor of this region was 2.5-fold (250%) compared to the average B-factor of the whole molecule (Figure 2, upper). By comparison, in CE208A, the electron density map in this region was clearly resolved (Figure 2, bottom), and the B-factor of the region was only slightly higher than the average B-factor of the whole molecule (Figure 2, upper).

Figure 2. Mutations caused increased flexibility in protein structure.

Average B-factor of the small lobe (2, grey), large lobe (3, tan), glycine-rich loop (4, yellow) and the αH-αI loop (5, red) was calculated using CNS_Solve 1.2, and compared to the average B-factor of the corresponding whole molecule (1, black). Residues are colored by atom types (N, blue, O, red, C, yellow). The zoom view shows the electron density map of the αH-αI loop region 275VDLTKRFNLKN286 in CR280A (top) and CE208A (bottom) structures. Electron density map of the same region in the wild type structure is very similar to that of CE208A. Two segments (left, residues 274–279, right, residues 279–286) were shown for a better view. Side chains of most residues in this region except Phe281 were disordered (A in the parenthesis indicated that the residue was replaced by Ala in the refinement). 2Fo-Fc electron density map was contoured at 1σ level.

For CE208A, the electron density and B-factor of the αH-αI loop region are similar to the wild type protein (Figure 2, bottom). Notably, the glycine-rich loop in CE208A exhibited higher temperature B-factors, compared to the wild type protein or CR280A (Figure 2, upper). When comparing B-factors of different segments within the same molecule, the glycine-rich loop has been shown to be one of the low B-factor regions in the wild type C-subunit ternary complex. As shown in Figure 2 (upper), in CR280A as well as the wild type C-subunit ternary structures, the B-factor for the glycine-rich loop was ~ 65–75% of that of the same whole molecule, whereas in CE208A, the B-factor for the glycine-rich loop was ~ 140% of the average B-factor of the whole molecule. Thus the B-factor for the glycine-rich loop in CE208A had a nearly 2-fold increase when comparing with the wild type protein. This is consistent with the enzyme kinetic data where it showed CE208A had a 13-fold higher Km for ATP than that of the wild type protein.

Disruption of the hydrophobic network that bridges the Activation segment and the GHI subdomain

By careful examination of the Arg280 and Glu208 environment in the wild type, we found that the aliphatic side chains of Glu208 and Arg280 contribute to extend the hydrophobic core network in the large lobe centered by the two highly conserved and buried αE and αF helices. This network connects the co-evolved Activation segment and the GHI subdomain in EPKs. Arg280 packs immediately against Leu277 from the αH-αI loop, and Leu277 in turn packs against the aliphatic part of Glu208, Ala218 and Trp222 from the αF helix. The interaction directly connects the αH-αI loop to the Activation segment (Figure 3A, center). In the CR280A mutant, loss of the Arg280 side chain broke the continuity of this hydrophobic network (Figure 3A, left). Similarly, in the CE208A mutant, loss of the Glu208 side chain also broke the hydrophobic continuity from the αH-αI loop to the Activation segment. However, the hydrophobic interactions within the αH-αI loop, and the connection between the αH-αI loop to the αF-helix were maintained (Figure 3A, right).

Figure 3.

A) Comparison of the Glu/Ala208 and Arg/Ala280 sites in CE208A (right), CR280A (left) and the wild type C-subunit (center). The turquoise spheres represent the water molecules that occupy void space caused by the mutations. The color scheme for the stick representation of residues is by atom types; N, blue, O, red, C, grey). Connolly surface was calculated from Leu277, Ala218 and the aliphatic parts of Glu208, Asp283, Glu274 and Arg280, and shown in 40% transparency colored in light grey. B) Hydrophobic environment of Glu208-Arg280 pair is highly conserved. Left, PKA (PDB ID 1L3R), right, CDK2 (PDB ID 1FIN). In PKA Leu277 from the αH-αI loop and Ala218 from the αF-helix caps the ion-pair of Glu208-Arg280. In CDK2, Pro271 and Ala183 achieve the same function to shield its Glu-Arg ion pair from solvent. C) Solvent accessible surface area (ASA) of Glu208 and Arg280 compared to selected surface exposed Glu or Arg residues in PKA. ASA was calculated on the PISA server43, using a probe of 1.6Å. ASA values of two fully solvent exposed arginines, Arg194 and Arg256 were averaged as comparison. Similarly, ASA of two fully solvent exposed glutamic acids, Glu248 and Glu331 were also averaged for comparison.

Increased solvation and maintaining of polar interactions at the mutation sites

In CE208A two water molecules W565 and W566 occupied the void created by the Ala replacement of Glu208 and made hydrogen-bond interactions with the guanidino-group of Arg280 as seen in the wild type protein. W565 also made a hydrogen-bond interaction with the amide nitrogen of Ala208, similarly as seen in wild type where Glu208:OE2 hydrogen-bonds with its own amide nitrogen atom (Figure 3A, right).

In CR280A, three water molecules occupied the void space left by NH1 (W931), NH2 (W934), and NE (W973). The four hydrogen bond interactions made through NH1, NH2 and NE atoms of Arg280 in the wild type protein were all replaced by interactions with the three water molecules (Figure 3A, left). These interactions are Arg280:NH1-Glu208:OE1; Arg280:NH1-Ala218:O, Arg280:NH2-Glu208:OE2, Arg280:NE-Gln274:O.

Interestingly, a fourth water molecule (W935) was found in close proximity to the aliphatic part of the Arg280 side chain, and formed a water network with the 3 water molecules mentioned above(Figure 3A, left). W935 was not present in other PKA C-subunit structures where Arg280 and Glu208 are intact. Thus the mutations, especially the Arg280 to Ala, brought a solvent network in place of the originally hydrophobic environment.

Buried Glu208-Arg280 salt bridge in eukaryotic kinases

Studies have shown that a buried salt bridge usually contributes to stabilization of a protein. The large decrease in energy resulting from the perfect geometry of the salt bridge interaction in the hydrophobic environment often exceeds the desolvation penalty15. The wild type and the two mutant structures clearly indicated that despite the polar interactions, the residues were in a hydrophobic environment. The structure showed that Leu277 from the αH-αI loop and Ala218 from the αF-helix form a hydrophobic cap shielding the ion-pair from the solvent (Figure 3B, left). Interestingly, at the position of Leu277, most protein kinases have a Pro. We examined several kinases from different subfamilies, and found that the Pro functions similarly to Leu277 to shield the Glu-Arg pair from the solvent, as exemplified by cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) (Figure 3B, right). Solvent accessible surface area (ASA) calculation of wild type PKA confirmed that both Glu208 and Arg280 residues were excluded from the solvent (Figure 3C). By comparison, ASA of two surface exposed Glu and two surface exposed Arg residues were also calculated. The average ASA for exposed Glu and Arg were 127 Å2, and 174 Å2, respectively. The ASA for Glu208 was 3.9 Å2, and for Arg280, the value was 0.0 Å2.

Increased dynamics of the αH-αI loop and the catalytic loop in apo-CE208A and CR280A monitored by hydrogen/deuterium exchange

It has been shown from previous studies that binding of MgATP and IP20 peptide helps to stabilize the C-subunit, and shields away some dynamic features of the protein. Unfortunately, efforts on crystallizing the apo-form of the mutants without MgATP and IP20 did not yield crystals. In order to examine the dynamic effects of the mutants without the influence of the MgATP and IP20, we carried out solution hydrogen/deuterium exchange studies 16,17 of the mutants in their apo-forms.

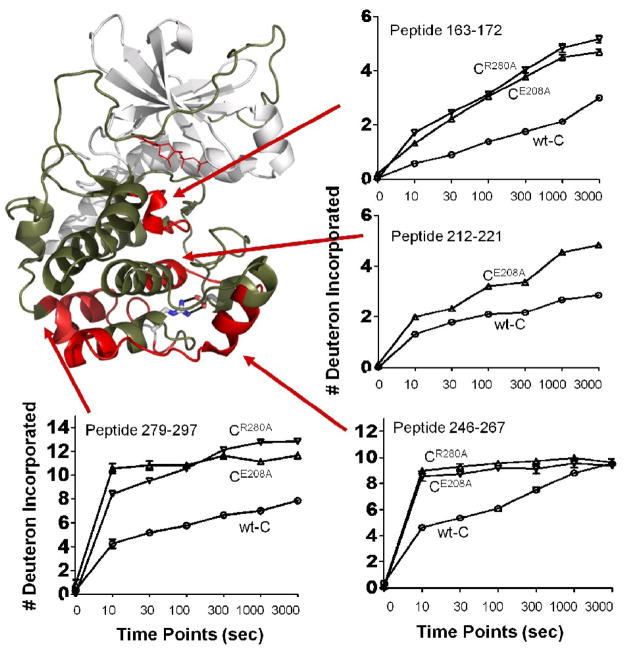

For both CE208A and CR280A, increased H/D exchange rate was observed in at least three regions (Figure 4). Representative peptides include peptide 163–172 from the Catalytic Loop, 247–267 from the αG and αG-αH loop, and 279–297 from the αH-αI loop containing Arg280Ala. Increased exchange was also observed for peptide 212–221 in CE208A; this peptide was at the loop connecting the APE motif and the αF-helix, we thus term it APE-F linker. Unfortunately, similar peptides were not recovered in CR280A samples. The difference in H/D exchange reflected on the total number of deuterons incorporated to the peptides and also on the kinetics of the exchange. During the course of 10 seconds to 50 minutes, peptides 163–172 from both mutants and 212–221 from CE208A gradually picked up 2 and 4 more deuterons, respectively, than the same peptides from the wild type C-subunit. Peptides 247–267 and 279–297 each showed faster kinetics in the mutant enzymes by picking up almost the maximum number of deuterons at the first 10 second time points, whereas in the wild type protein, the peptides gradually reached the maximum deuteron exchanges during the course of 50 minutes (Figure 4). It is interesting to note that from the crystal structure of CE208A ternary complex, all four of these regions did not show significant relative increase of temperature B factors compared to the wild type ternary complex structure. It is likely that indeed the presence of MgATP and IP20 stabilized the structure and thus H/D exchange of the apo enzyme did help to reveal some of the dynamic regions of the protein that resulted from the mutations and were masked in the crystal structures. However, for CR280A, the effect on the destabilization of the αH-αI loop was quite substantial that even the presence of MgATP and IP20 could not stabilize it as observed for CE208A.

Figure 4. Comparison of hydrogen deuterium exchange profiles of CE208A, CR280A and the wild type C-subunit.

Crystal structure of the wild type C-subunit is rendered in cartoon representation with the N-lobe colored white and the C-lobe colored tan. Regions that exhibit increased H/D exchange in the mutants are colored red. Comparison of the time course of H/D exchange profile for four peptides in CE208A ( triangle), CR280A (reversed triangle) and wild type C-subunit (circle) are shown. Time points are indicated.

Decreased folding stability of CR280A and CE208A

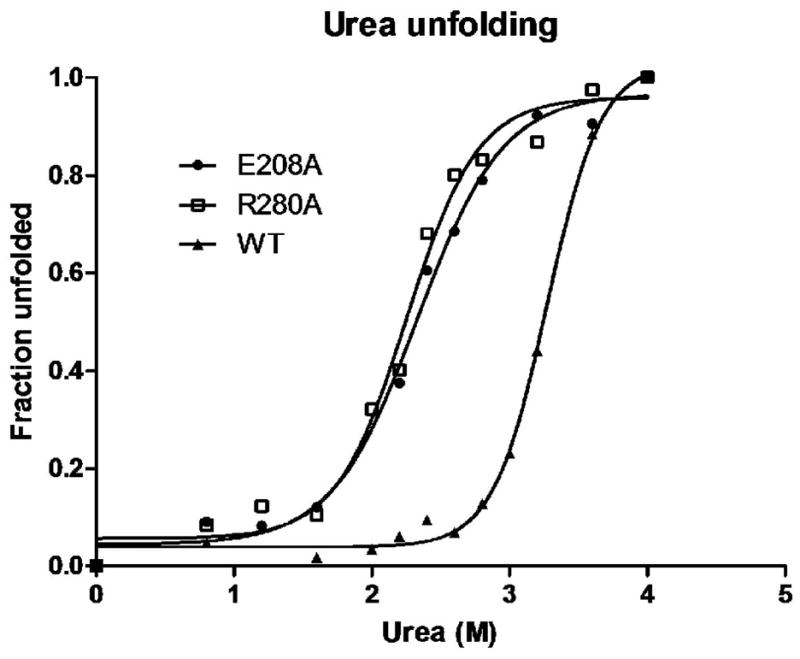

Above data showed that in the absence of ligands, such as MgATP and IP20, both CR280A and CE208A exhibited increased H/D exchange rates in regions mainly in the large lobe of the protein molecule. The large lobe is comprised of a stable hydrophobic core centered by the αE and αF helices; most loop regions outside the core showed increased H/D exchange rates. We reasoned that either Glu208Ala or Arg280Ala mutation would likely decrease the stability of the protein. To assess the effect by each mutation on the destabilization of the protein, we examined the protein unfolding in the presence of urea, and monitored the fraction of the unfolded protein through internal fluorescent signal. As shown in Figure 5, the concentration of urea required to unfold 50% of the protein for CR280A and CE208A were both 2.2 M, lower as compared to 3.2 M required for the wild type protein.

Figure 5. Decreased folding stability of CE208A and CR280A.

Urea-denaturation curves for WT, CE208A and CR280A were compared. The fraction of protein unfolded is shown as a function of urea concentration as measured by intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence.

Reduced efficiency for CE208A and CR280A phosphorylation by upstream kinase PDK1

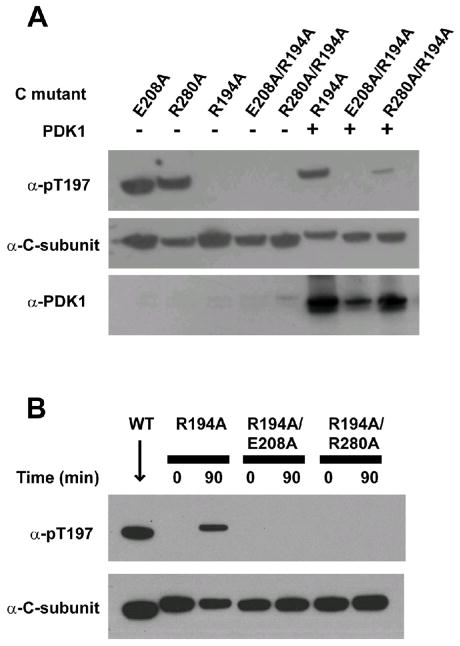

PDK1 has been shown to phosphorylate the C-subunit at the Thr197 site18, the key residue of which phosphorylation is necessary to render the kinase fully active. The detailed interactions between PDK1 and PKA are not clear. Earlier work showed that residues from the Activation segment including Glu208 affected the phosphorylation of C-subunit by PDK118. We therefore examined whether Arg280Ala mutation also affected PDK1 phosphorylation. It has been shown that when expressed in E.coli, wild type C-subunit gets autophosphorylated at Thr19719, due to the consensus PKA recognition sequence at the region: 190RVKGRTWTL198. This hinders the study of phosphorylation by PDK1. To overcome the problem, an Arg194Ala mutation has been introduced to eliminate the autophosphorylation at Thr197, and it has been shown that the effect of Arg194Ala itself to other properties of the kinase is not significant, since after phosphorylation at Thr197 by PDK1, the Arg194Ala mutant behaved very much like the wild type enzyme in many ways20.

Like the wild type C-subunit, both CR280A and CE208A were autophosphorylated at Thr197 when expressed in E. coli (Figure 6A). Taking advantage of the known fact that Arg194Ala mutation prevented the autophosphorlyation at Thr197 by destroying the PKA recognition site, we generated two double mutants CR194A/R280A and CR194A/E208A to study the effects of the ion-pair mutation on phosphorylation by PDK1. As shown in Figure 6, Arg194Ala mutation indeed prevented autophosphorylation as shown earlier. Under similar level of protein expression for all the mutants and the wild type protein, while CR194A was readily phosphorylated by PDK1, phosphorylation of either CR194A/R280A or CR194A/E208A by PDK1 was greatly reduced (Figure 6A). Results were reproduced with in vitro phosphorylation carried out with purified proteins. As shown in Figure 6B, purified PDK1 can phosphorylate purified CR194A, but not CR194A/E208A nor CR194A/R280A proteins.

Figure 6. Glu208 or Arg280 is essential for phosphorylation of PKA by PDK1.

A) C-subunit mutants were expressed overnight at 16°C, either alone or with PDK1, in E. coli, and the soluble fraction of the cell lysates were immunoblotted for phospho-Thr197 phosphorylation, C-subunit, and PDK1. B) Purified PDK1 was incubated with purified mutants His(6)-CR194A, His(6)-CR194A/E208A, and His(6)-CR194A/R280A and Mg-ATP for 90 min at room temperature and immunoblotted for phospho-Thr197 phosphorylation and C-subunit. Untagged wild type C-subunit was loaded as an antibody control.

DISCUSSION

Because the eukaryotic protein kinases represent one of the largest gene families and have enormous impact for the regulation of biological events, they have been intensely studied over the past few decades. Although considerable attention has focused on the conserved residues that cluster around the active site cleft, little attention has been given to the conserved salt bridge in the C-lobe between Glu208 and Arg280 that lies distal to the active site (Figure 1B). Glu208 is part of the Activation segment, which is inserted into the C-lobe of the kinase core and is quite large and typically regulated by phosphorylation in the EPKs. Arg280 is part of the GHI subdomain, which serves as a protein docking site and is part of the EPK-specific allosteric network. The Activation segment and the GHI-subdomain emerge as structural elements that can play a critical role not only for docking of substrates and regulatory proteins but also for contributing to allosteric regulatory mechanisms.

By replacing Glu208 and Arg280 with Ala, we have elucidated the importance of this salt bridge for the activity and structural stability of the enzyme. The Glu208Ala and Arg280Ala mutants are each severely defective in their catalytic efficiency due primarily to an increased Km for ATP and a reduced kcat resulting in a kcat/Km(ATP) that is reduced by over two orders of magnitude (Table 1). Hydrogen/deuterium exchange experiments showed that the destabilizing effect of these mutations can be observed in the entire kinase structure and is not restricted to the immediate residues that surround the mutated site (Figure 4). The catalytic loop, the APE-F linker, the αH-αI loop and the αG-αH loop are all significantly more exposed to solvent in each mutant. This global destabilizing effect of the mutations is also supported by the urea unfolding assays (Figure 5) and by the inability of PDK1 to phosphorylate the Activation segments of both Glu208Ala and Arg280Ala mutants (Figure 6).

Crystal structures of the Glu208Ala and Arg280Ala mutants could be solved only in presence of MgATP and peptide inhibitor PKI. They did not show any global structural differences between the mutants and the wild type molecule, and that can be explained by stabilizing effect of MgATP and PKI. There was, however, a significant difference in the Arg280Ala mutant, which showed significant destabilization of the αH-αI loop that contains the mutated Arg280. This mutation caused more than a two-fold increase in the temperature factors for residues in this loop compared to the wild type structure or the Glu208Ala mutant (Figure 2). Side chains of almost all residues inside the αH-αI loop also were not resolved. Such destabilization of the loop in the Arg280Ala, but not in the Glu208Ala mutant, is consistent with the distinctive properties of the arginine side chain.

Neutron diffraction of guanidinium ions showed that their interaction with water molecules is very weak 21. In fact no recognizable hydration shell was detected around the guanidinium ions. This can be explained by incompatible geometric properties of these flat, rigid ions and tetrahedral molecules of water. This makes arginine a unique amino acid residue. On the one hand, it carries a positive charge on its guanidinium group and is capable of polar and charged interactions; on the other hand, it behaves almost as a hydrophobic residue, not only due to the aliphatic part of its side chain but also due to the poor ability of the guanidinium group to interact with water molecules. Such excessive hydrophobicity explains the fact that arginines in protein structures are usually more buried than can be expected from experimentally measured hydrophobicity 22. It is known that buried salt bridges often contribute to protein stability 15,23. Typically, a large desolvation penalty is thought to be related to these buried salt bridges. In case of arginine, however, such penalty may be overestimated due to the unique properties of this residue.

In accordance with these properties of arginine, the Glu208-Arg280 salt bridge has a hydrophobic environment that is conserved in different protein kinases. Toward the protein interior side, Arg280 packs against Trp222 from the αF-helix at the center of the hydrophobic core. To the surface side, Arg280 packs against Leu277, which provides a hydrophobic cap separating the Glu208-Arg280 salt bridge from solvent. These connections are reinforced by favorable geometry of hydrogen bonding to the Glu280 as well as interactions with nearby charged residues 15. In addition, the side chain of Arg280 is in hydrogen bonding distance to the main chain carbonyl oxygens of Gln274 and Ala218, and Glu208 makes hydrogen bonds to its own main chain nitrogen atom (Figure 3) as well as two water molecules in the wild type structures of PKA (PDB IDs 1L3R and 3FJQ).

Similar interactions can be observed in the structure of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (PDB ID 1FIN), besides the Glu-Arg interaction, each residue makes hydrogen bonds to several main chain atoms. This may contribute to the stability of the salt bridge in the otherwise hydrophobic environment. In the Glu208Ala or Arg280Ala mutants water molecules enter the hydrophobic pocket usually occupied by the Glu208-Arg280 salt bridge and, thus, destabilize this structurally important junction between the Activation segment and the GHI-subdomain.

It is intriguing to note that besides mediating signal relay within the molecule, both Glu208 and Arg280 may also contribute to the interaction with other proteins. Here we show that in contrast to the wild type protein, neither CE208A nor CR280A is phosphorylated by PDK1. It has been reported in several protein kinase structures that the highly conserved Glu208:Arg280 pair within one molecule swaps with the same pair in an adjacent molecule either in a naturally-occurring dimer or crystal packing induced dimer24–27. This observation provides an attractive hypothesis that when one kinase acts on another kinase, the switch/swapping of the conserved Glu208:Arg280 pair might serve as a mechanism for interaction. Whether this mechanism is true for PKA: PDK1 interaction awaits more experiments.

Several features emerge from this study that have relevance for the entire family. These include the unique importance of an arginine residue and the extended definition of the Activation segment to include the APE-αF helix (APE-F) linker that is located between the APE motif and the αF-helix. In the past we have considered the Activation segment to extend from the DFG motif at the N-terminus to the APE motif at the C-terminus. Included within this segment (Figure 1D) is the Mg positioning motif (DFG motif), β strand 9, the Activation Loop, the P+1 Loop and the APE motif. Almost every residue in this segment plays a specific role, and often that role is different in the active vs. inactive conformation of the enzyme. The DFG motif through the Activation Loop can be ordered very differently when the kinase is not phosphorylated on the Activation Loop, and under these conditions the Regulatory Spine is broken which is typical for most inactive kinases2. Both the Activation segment and the GHI subdomain are firmly anchored to the hydrophobic αF-helix and are thus part of the core architecture that defines this family and distinguishes the EPKs from the larger family of eukaryotic-like kinases1,2. Three residues, that were found to be conserved in all GHI-subdomains 1: Pro237, Phe238, and Ile250 form a hydrophobic cluster that binds to the APE-alanine and proline (Figure 1C). This cluster docks to the conserved Trp222 in the αF-helix which serves as a centerpiece of the conserved protein kinase core 28. From this study we see clearly that the segment extending from the APE motif to the αF helix is also an important part of the Activation segment (Figure 1D).Regulatory subunits 3,29,30, substrates 31, phosphatases 32 and other protein kinase molecules 33,34 dock to the junction between the N-terminal part of the APE-F linker and the αG-helix (Figure 1C).In some kinases, such as Csk, there are key phosphorylation sites in the C-terminal part of APE-F linker35, and these sites can now be considered more carefully in terms of their potential to have importance for regulation. While further studies will be required to demonstrate the full importance of this buried salt bridge in different kinases, we already have indications that this region has biological significance. It was demonstrated previously that the αH-αI loop is not only a distal tethering site for certain PKA substrates but is also a key allosteric site for PKA and that this region has the capacity to feed back to the active site6. The mutations of Glu208 and Arg280 confirm this mechanism for feedback to the site of catalysis. Other kinases such as the MAP kinases have an insert in this region which feeds back to the activation segment and allows for further integration of the Activation segment and GHI subdomains. Finally, it was found that germ line mutations in Glu208 and Arg280 are a hot spot for disease association suggesting that mutations in the region may prime an individual for subsequent disease phenotypes36. Our analyses of this conserved salt bridge and its importance for the function and stability of PKA suggests that other kinases should be revisited and examined for the functional relevance of this region that has co-evolved to be such a unique and important feature of the EPKs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Inhibitory peptide IP20 (TTYADFIASGRTGRRNAIHD, residues 5–24 from the heat stable PKA inhibitor PKI) was synthesized on a Milligen peptide synthesizer and purified by high performance liquid chromatography. Pre-packed Mono S 10/10 ion exchange column and Superdex 75 gel filtration column were purchased from GE Healthcare. Crystallization reagents PEG6000, MPD (2-Methyl-2,4-pentanediol), Bicine, glycerol, and ammonium acetate were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Other reagents were from Qiagen, Life Technology, and EMD Biosciences. Polycolonal phospho-Thr197 antibody was raised in rabbits against the epitope peptide RVKGRTWpTLCGTPEY(Life Technology). The PDK1 antibody, which recognizes residues 538–556 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The PKA catalytic subunit antibody was purchased from BD Biosciences. Purified phosphatase inhibitors, which were used here as PKA substrates, DARPP-32 and PP1_I-2 were gifts from Dr. James Bibb (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX), and Dr. Shirish Shenolikar (Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC), respectively. His(6)-tagged phosphoinositide dependent kinase 1 was a gift from Dr. Alexandra Newton (University of California, San Diego, CA) and was expressed in bacculovirus-infected Spodoptera frugiperda (SF9) cells. The protein was purified on a Profinia protein purification system (Bio-Rad) with a Ni-affinity column and eluted with imidazole buffer.

Purification of C-subunit Mutants

C-subunit mutations of Arg280Ala and Glu208Ala were introduced to the murine PKA Cα subunit in pRSET vectorusing the QuikChange kit (Agilent Technologies, USA). The same mutations were also introduced separately in the His(6)-tagged C-subunit in pET15b vector containing the Arg194Ala mutation20 Both CE208A and CR280A mutants were expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells and purified using P11 resin followed by cation exchange chromatography on pre-packed Mono S 10/10 column (GE Healthcare), as described previously37. For both mutants, ion-exchange peaks corresponding to two phosphorylated residues, Thr197 and Ser338, were used for our studies. The His(6)-CR194A/E208A and His(6)-CR194A/R280A proteins were purified through Probond resin (Invitrogen). Briefly, the cell pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, plus with protease inhibitors (5 mM benzamidine, 0.5 mM 4-(2-Aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride (AEBSF), 30 μM each of Nα-tosyl-L-phenylalanine chloromethyl ketone (TPCK) and Nα-tosyl-L-lysine chloromethylketone (TLCK)). The cells were lysed in a microfluidizer at 18,000 psi and spun down by centrifugation at 30,000 g for 45 min at 4°C. The lysate was incubated with Probond resin for 1 hour at 4°C. The resin was washed with lysis buffer containing 1 M NaCl followed by 20 mM imidazole. The protein was then eluted with lysis buffer containing 100–300mM imidazole.

Enzyme kinetic assay

Kinetic analysis of the mutant and the wild-type C-subunits were performed by radioisotope γ-32P-ATP labeling as described previously 38, using peptide substrate Kemptide (LRRASLG), or protein substrates DARPP-32 or PP1_I-1. To measure the Km for ATP, ATP concentration was varied while the concentration of Kemptide was fixed at 250 μM. To determine the Km for Kemptide, the ATP concentration was fixed at 250 μM for the wild type and the CR280A mutant, and at 500 μM for CE208A, with Kemptide concentration varied from 2μM to 500 μM. To determine Km for protein substrates, concentration of DARPP-32 or PP1_I-1 was varied from 0.5 μM to 40 μM. Enzyme was diluted in 20 mM HEPEs, pH7.0, 1mg/mLbovine serum albumin (BSA), plus 0.2% β-β-mercaptoethanol. The assay was carried out in 20 mM HEPEs, pH 7.0, 10 mM MgCl2, with varied enzyme and substrates. BSA of 0.2 mg/mL was also included in the assay to prevent nonspecific loss of diluted enzyme to the assay tube. Final concentration of the enzyme in the assay was 0.5–1 nM for the wild type and 5–10 nM for the CE208A or CR280A. Reaction mix of 20 μL was incubated at 30°C for 10 min and then quenched with 20 μL of 40% acetic acid. Paper chromatography on phosphocellulose paper (Whatman P81)was used to separate unreacted γ-32P-ATP from the protein bound radioactivity. Radioactivity was measured by Cerenkov counting on Beckman LS 6000SC liquid scintillation system38.

Crystallization of CE208A and CR280A

For crystallization, the protein from a Mono S column was further purified on a Superdex 75 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) and eluted with 50 mM Bicine, 200 mM ammonium acetate, pH 8.0, plus 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The protein was concentrated to 7–10 mg/mL and mixed with MgCl2, ATP, and IP20 at a molar ratio of 1:10:10:10 before setting up the crystallization trials. Hanging-drop vapor diffusion was used; each drop consisted of 1 μL of the protein mixture and 1 μL of well solution. Crystals appeared after 1–2 weeks at 4 °C. For CE208A, the well conditions consisted of 10–12 % (W/V) polyethylene glycol 6000, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, plus 10 mMDTT. For CR280A, crystals appeared at well conditions of 13–15% (V/V) MPD, 100 mM Bicine, pH 8.0, plus 10 mM DTT.

Data Collection and Structure Refinement

A 1.7 Å dataset for CR280A and 1.9Å dataset for CE208A were collected at Advanced Light Source (Berkeley, CA) beamline 8.2.2 or 8.2.1 at synchrotron source. Data collection was performed under a liquid nitrogen stream. The cryo-protectant consisted of 1–2% higher precipitant concentration, plus 15% glycerol. The data set was processed and scaled using HKL2000 (23). Molecular replacement was performed using wild type C-subunit ternary structure (PDB ID 1ATP) as the searching model. Structure refinement was carried out using CNS Solve 1.2 39. The statistics are shown in Table 1. CR280A crystallized in a “canonical” PKA C-subunitternary complex space group P212121, with cell dimensions similar to those for most C-subunit crystals, and one molecule in each asymmetric unit (for example, PDB ID 1ATP, 1L3R, 3FJQ). However, the space group for CE208A was P21 (Table 1). It also has only one molecule in each asymmetric unit. For most of the C-subunit structures, including CR280A solved in this study, the first 10–14 residues of the protein are often disordered, making the N-terminal αA-helix usually starting from residue 11 or 15. In CE208A structure, however, the full N-terminal αA-helix was well resolved. It formed a straight helix as seen in two other C-subunit mutant structures reported previously. One was a mutant where four residues at the ATP binding site were mutated (Gln84Glu, Val123Ala, Leu173Met, and Phe187Leu) (PDB ID 1SMH) 40, and the other was the structure of a Glu230Gln mutant (PDB ID 1SYK) 41. The significance of the ordering of the full αA-helix was not clear.

Hydrogen/Deuterium exchange analysis

Preparation of deuterated samples and subsequent DXMS analysis was carried out as previously described 42. Briefly, the deuterium exchange reaction was started by combining 5 μL of protein sample (5 mg/mL, or 0.125 mM, mutant or wild type C-subunit) with 15 μL of 20 mM Mops (pH 7.4), 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT in 2H2O (deuteration buffer). After incubation at room temperature for various amount of time, 10, 30, 100, 300, 1000, or 3000 seconds, the reaction was quenched with 30 μL of 0.8% (v/v) formic acid, 1.6 M guanidine-HCl in 2H2O, pH 2.3–2.5 at 0 °C. Samples were immediately passed through a solid-phase pepsin column followed by a V8 protease column, and eluted with 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) at 0.2 ml/minute for two minutes. Proteolytic peptides were collected by a C18 column (Vydac), which was subsequently developed with a linear gradient of 10 ml of 8%–40% (v/v) acetonitrile in 0.05% TFA, at 0.2 ml/minute. Mass spectrometric analysis was carried out with a Finnigan LCQ mass spectrometer as previously described 42. Recovered peptide identification and analysis were carried out using in-house software specialized in processing DXMS data17.

Urea Unfolding and Fluorescence Measurements

Amberlite MB-150 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) mixed-bed exchanger was added to 8.0 M urea solution and stirred for 1 h to remove ionic urea degradation products and then filtered. Proteins (0.12 mg/mL) were unfolded in various concentrations of urea ranging from (0 – 4 M) for 0.5 h at room temperature and monitored by steady-state fluorescence. Fractional unfolding curves were constructed assuming a two-state model and using FU = 1 - [(R - RU)/(RF - RU)], where FU is the fraction of the unfolded protein, R is the fluorescence measurement, and RF and RU represent the values of R for the folded and unfolded states, respectively. For unfolding monitored by fluorescence, R is the observed ratio of intensity at 356/334 nm with excitation at 295 nm.

Phosphorylation of His(6)-CR194A/E208A and His(6)-CR194A/R280A mutants by PDK1

PDK1 phosphorylation of the C-mutants was examined by coexpression of His(6)-CR194A/E208A or His(6)-CR194A/R280A with PDK1 in E. coli cells, and by in vitro phosphorylation using purified proteins. His(6)-CR194A/E208A, His(6)-CR194A/R280A or His(6)-CR194A was co-expressed with PDK1 in pGEXvector in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells overnight at 16°C. Cells were lysed by sonication in 50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.0 and the insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 15,000 g for 30 min. The soluble fraction was subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and blotted for phospho-Thr197, C-subunit, and PDK1. For the in vitro assay, 0.1 mg/mL of purified His(6)-CR194A/E208A, His(6)-CR194A/R280A or His(6)-CR194A proteins were incubated with 0.002 mg/mL purified PDK1 in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT,10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, at room temperature for 90 min. The reaction was quenched in SDS-sample buffer, and probed for phospho-Thr197 by western blot analysis.

Highlights.

In this study we study structural stability of cAMP dependent protein kinase

We mutated two residues that form a universally conserved salt bridge inside the protein kinase core

Structural and biochemical studies of these mutants demonstrate that this salt bridge is important for overall stability of the whole protein kinase molecule

These results are important for understanding of protein kinase function and molecular evolution of these enzymes

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Malik Keshwani for purifying the PDK1 from insect cells.

Funding: This work is supported by GM19301 to S.S.T. Additional support to J.M.S. was provided in part by the UCSD Graduate Training Program in Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology through an institutional training grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, T32 GM007752.

Footnotes

Accession numbers: Coordinates have been deposited at the Protein Data Bank with accession codes 3QAM (CE208A structure) and 3QAL (CR280A structure).

Author contributions: J.Y. crystallized the proteins, performed H/D exchange, enzyme kinetic analysis, and structural determination and analysis. J.W. solved the structures. J.M.S. performed the stability assay and PDK1 phosphorylation assay. A.P.K. performed structural analysis. M.S.D. purified the proteins. S.L. worked on H/D exchange data collection. B.S. collected X-ray data at synchrotron. V.L.W. oversaw the H/D experiments. S.S.T. oversaw the entire project. J.Y., J.M.S., A.P.K., J.W. and S.S.T. wrote the paper.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kannan N, Neuwald AF. Did protein kinase regulatory mechanisms evolve through elaboration of a simple structural component? J Mol Biol. 2005;351:956–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor SS, Kornev AP. Protein kinases: evolution of dynamic regulatory proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:65–77. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu J, Brown SH, von Daake S, Taylor SS. PKA type IIalpha holoenzyme reveals a combinatorial strategy for isoform diversity. Science. 2007;318:274–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1146447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diskar M, Zenn HM, Kaupisch A, Kaufholz M, Brockmeyer S, Sohmen D, Berrera M, Zaccolo M, Boshart M, Herberg FW, Prinz A. Regulation of cAMP-dependent protein kinases: the human protein kinase X (PrKX) reveals the role of the catalytic subunit alphaH-alphaI loop. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:35910–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.155150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim C, Cheng CY, Saldanha SA, Taylor SS. PKA-I holoenzyme structure reveals a mechanism for cAMP-dependent activation. Cell. 2007;130:1032–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deminoff SJ, Ramachandran V, Herman PK. Distal recognition sites in substrates are required for efficient phosphorylation by the cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Genetics. 2009;182:529–39. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.102178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torkamani A, Kannan N, Taylor SS, Schork NJ. Congenital disease SNPs target lineage specific structural elements in protein kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9011–9016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802403105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor SS, Kim C, Vigil D, Haste NM, Yang J, Wu J, Anand GS. Dynamics of signaling by PKA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1754:25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor SS, Yang J, Wu J, Haste NM, Radzio-Andzelm E, Anand G. PKA: a portrait of protein kinase dynamics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1697:259–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2003.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson DA, Akamine P, Radzio-Andzelm E, Madhusudan, Taylor SS. Dynamics of cAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2243–70. doi: 10.1021/cr000226k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Svenningsson P, Nishi A, Fisone G, Girault JA, Nairn AC, Greengard P. DARPP-32: an integrator of neurotransmission. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:269–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Endo S, Zhou X, Connor J, Wang B, Shenolikar S. Multiple structural elements define the specificity of recombinant human inhibitor-1 as a protein phosphatase-1 inhibitor. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5220–8. doi: 10.1021/bi952940f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore MJ, Adams JA, Taylor SS. Structural basis for peptide binding in protein kinase A. Role of glutamic acid 203 and tyrosine 204 in the peptide-positioning loop. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:10613–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210807200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng J, Knighton DR, Ten Eyck LF, Karlsson R, Xuong NH, Taylor SS, Sowadski JM. Crystal Structure of the Catalytic Subunit of cAMP-dependent Protein Kinase Complexed with MgATP and Peptide Inhibitor. Biochemistry. 1993;32:2154–2161. doi: 10.1021/bi00060a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar S, Nussinov R. Salt bridge stability in monomeric proteins. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:1241–55. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Englander JJ, Del Mar C, Li W, Englander SW, Kim JS, Stranz DD, Hamuro Y, Woods VL., Jr Protein structure change studied by hydrogen-deuterium exchange, functional labeling, and mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7057–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232301100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woods VL, Jr, Hamuro Y. High resolution, high-throughput amide deuterium exchange-mass spectrometry (DXMS) determination of protein binding site structure and dynamics: utility in pharmaceutical design. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 2001;37:89–98. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore MJ, Kanter JR, Jones KC, Taylor SS. Phosphorylation of the Catalytic Subunit of Protein Kinase A. Autophosphorylation versus Phosphorylation by Phosphoinositide-dependent Kinase-1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:47878–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204970200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yonemoto W, McGlone ML, Grant B, Taylor SS. Autophosphorylation of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase in Escherichia coli. Protein Eng. 1997;10:915–25. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.8.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steichen JM, Iyer GH, Li S, Saldanha SA, Deal MS, Woods VL, Jr, Taylor SS. Global consequences of activation loop phosphorylation on protein kinase A. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3825–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.061820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mason PE, Neilson GW, Dempsey CE, Barnes AC, Cruickshank JM. The hydration structure of guanidinium and thiocyanate ions: implications for protein stability in aqueous solution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4557–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0735920100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samanta U, Bahadur RP, Chakrabarti P. Quantifying the accessible surface area of protein residues in their local environment. Protein Eng. 2002;15:659–67. doi: 10.1093/protein/15.8.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar S, Ma B, Tsai CJ, Nussinov R. Electrostatic strengths of salt bridges in thermophilic and mesophilic glutamate dehydrogenase monomers. Proteins. 2000;38:368–83. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(20000301)38:4<368::aid-prot3>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee SJ, Cobb MH, Goldsmith EJ. Crystal structure of domain-swapped STE20 OSR1 kinase domain. Protein Sci. 2009;18:304–13. doi: 10.1002/pro.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oliver AW, Knapp S, Pearl LH. Activation segment exchange: a common mechanism of kinase autophosphorylation? Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:351–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pike AC, Rellos P, Niesen FH, Turnbull A, Oliver AW, Parker SA, Turk BE, Pearl LH, Knapp S. Activation segment dimerization: a mechanism for kinase autophosphorylation of non-consensus sites. EMBO J. 2008;27:704–14. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sunami T, Byrne N, Diehl RE, Funabashi K, Hall DL, Ikuta M, Patel SB, Shipman JM, Smith RF, Takahashi I, Zugay-Murphy J, Iwasawa Y, Lumb KJ, Munshi SK, Sharma S. Structural basis of human p70 ribosomal S6 kinase-1 regulation by activation loop phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:4587–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.040667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kornev AP, Taylor SS, Ten Eyck LF. A helix scaffold for the assembly of active protein kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14377–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807988105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown SH, Wu J, Kim C, Alberto K, Taylor SS. Novel isoform-specific interfaces revealed by PKA RIIbeta holoenzyme structures. J Mol Biol. 2009;393:1070–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim C, Xuong NH, Taylor SS. Crystal structure of a complex between the catalytic and regulatory (RIalpha) subunits of PKA. Science. 2005;307:690–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1104607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dar AC, Dever TE, Sicheri F. Higher-order substrate recognition of eIF2alpha by the RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR. Cell. 2005;122:887–900. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song H, Hanlon N, Brown NR, Noble ME, Johnson LN, Barford D. Phosphoprotein-protein interactions revealed by the crystal structure of kinase-associated phosphatase in complex with phosphoCDK2. Mol Cell. 2001;7:615–26. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eswaran J, Knapp S. Insights into protein kinase regulation and inhibition by large scale structural comparison. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:429–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor SS, Haste NM, Ghosh G. PKR and eIF2alpha: integration of kinase dimerization, activation, and substrate docking. Cell. 2005;122:823–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vang T, Torgersen KM, Sundvold V, Saxena M, Levy FO, Skalhegg BS, Hansson V, Mustelin T, Tasken K. Activation of the COOH-terminal Src kinase (Csk) by cAMP-dependent protein kinase inhibits signaling through the T cell receptor. J Exp Med. 2001;193:497–507. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.4.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Torkamani A, Kannan N, Taylor SS, Schork NJ. Congenital disease SNPs target lineage specific structural elements in protein kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9011–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802403105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herberg FW, Bell SM, Taylor SS. Expression of the Catalytic Subunit of cAMP-dependent Protein Kinase in E. coli: Multiple Isozymes Reflect Different Phosphorylation States. Prot Eng. 1993;6:771–777. doi: 10.1093/protein/6.7.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang J, Kennedy EJ, Wu J, Deal MS, Pennypacker J, Ghosh G, Taylor SS. Contribution of non-catalytic core residues to activity and regulation in protein kinase A. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6241–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805862200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–21. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Breitenlechner C, Engh RA, Huber R, Kinzel V, Bossemeyer D, Gassel M. The typically disordered N-terminus of PKA can fold as a helix and project the myristoylation site into solution. Biochemistry. 2004;43:7743–9. doi: 10.1021/bi0362525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu J, Yang J, Kannan N, Madhusudan, Xuong NH, Ten Eyck LF, Taylor SS. Crystal structure of the E230Q mutant of cAMP-dependent protein kinase reveals an unexpected apoenzyme conformation and an extended N-terminal A helix. Protein Sci. 2005;14:2871–9. doi: 10.1110/ps.051715205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang J, Garrod SM, Deal MS, Anand GS, Woods VL, Jr, Taylor S. Allosteric network of cAMP-dependent protein kinase revealed by mutation of Tyr204 in the P+1 loop. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:774–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]