Abstract

We report an experimental and computational study of 3-silylarynes. The addition of nucleophiles yield ortho-substituted products as a result of aryne distortion, but meta-substituted products form predominately when the nucleophile is large. Computations correctly predict the preferred site of attack observed in both nucleophilic addition and cycloaddition experiments. Nucleophilic additions to 3-t-butylbenzyne, which is not significantly distorted, give meta-substituted products.

Despite once being a subject of controversy,1 arynes are now a thriving area of chemical discovery.2 Modern methods of aryne generation have led to greater control of reactivity, thus enabling the use of arynes in a host of synthetic applications.3 Nonetheless, the control and understanding of regioselectivity in reactions of unsymmetrical arynes remains an important area of research.2

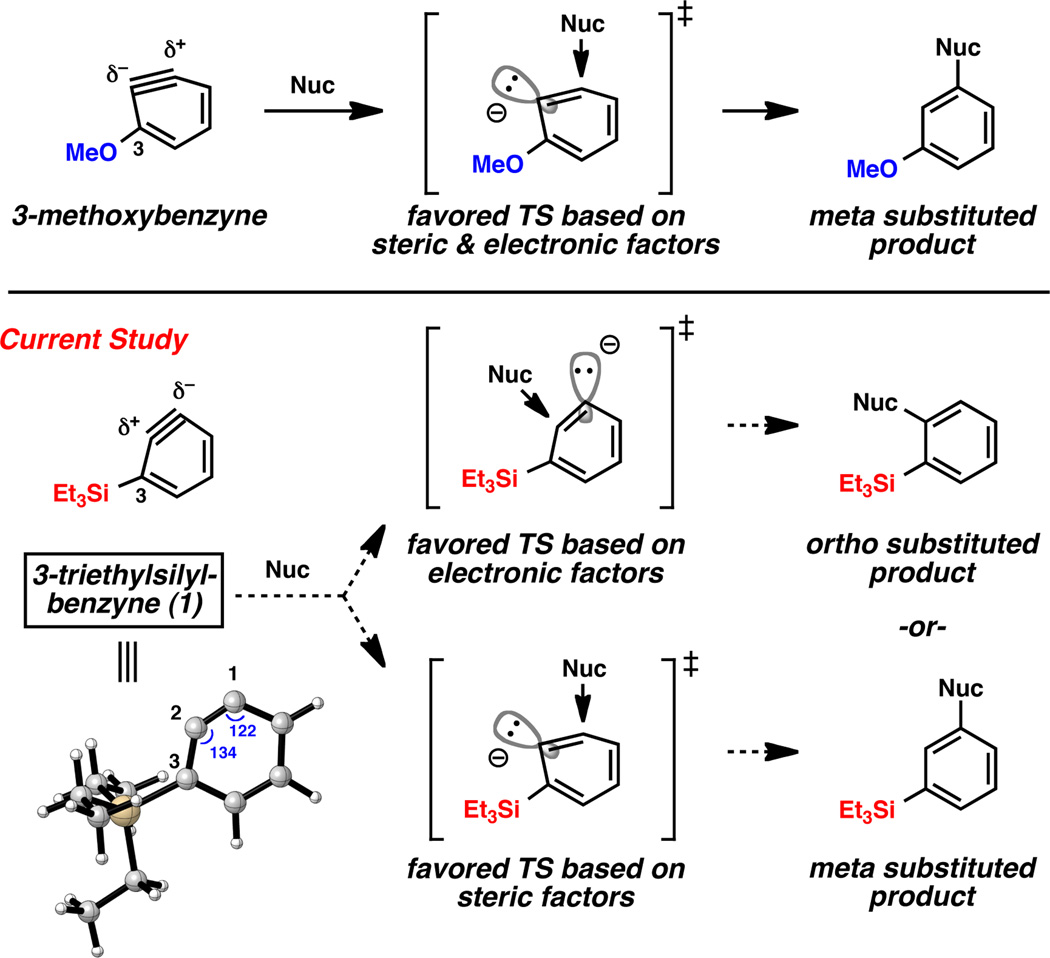

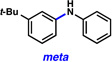

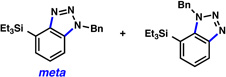

The aryne distortion model, reported by our laboratories in 2010,4 shows that regioselectivity in nucleophilic additions and cycloadditions of arynes is governed by the inherent distortion present in unsymmetrical arynes and transition state distortion energies.5 The model allows for reliable regioselectivity predictions to be made using simple computations, and has been validated for ring-fused arynes and arynes that possess neighboring inductively withdrawing substituents.4,6 In the case of 3-methoxybenzyne,7 the aryne is pre-distorted as suggested in Figure 1. Addition of the nucleophile occurs at the more electrophilic site, with flattening at the carbon undergoing attack, to give meta-substituted products.8,9 As a means to further probe the aryne distortion model, we examined the influence of inductively donating silyl substituents on aryne regioselectivities.10 Our experimental and computational study demonstrates that the sense of regioselectivity in silylaryne reactions is variable, but aryne distortion can play a significant role. Computations correctly predict the preferred site of attack observed in both nucleophilic addition and cycloaddition experiments.

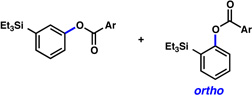

Figure 1.

Influence of 3-methoxy and 3-silyl substituents on aryne regioselectivity.

Geometry optimization of 3-triethylsilylbenzyne was conducted using DFT methods (B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p)).11 The silyl group severely distorts the aryne, such that the internal angles at C2 and C1 are 134° and 122°, respectively.12 Following the aryne distortion model, nucleophilic addition at C2, the more electropositive terminus of the aryne, is favored electronically; however, meta substitution should be preferred based on steric factors. Only few examples of silylaryne reactions have been reported, but it should be noted that additions of organolithium reagents to silylarynes occur with meta-selectivity,10a,b,c whereas additions of amines are primarily ortho-selective.10g,13

With the aim of studying regioselectivity patterns of silylarynes in a variety of nucleophilic addition and cycloaddition reactions, we prepared bis(silyl)triflate 5, which was envisioned to be a suitable precursor to triethylsilylbenzyne 1 (Scheme 1).14 Commercially available dibromophenol 2 was elaborated to known compound 315 via a two-step procedure involving O-silylation followed by halogen-metal exchange-mediated O to C migration of the silyl substituent.16 Next, an analogous sequence was employed to install the triethylsilyl group, thus providing 4.17 Triflation of 4 afforded the desired bis(silyl)triflate 5.18

Scheme 1.

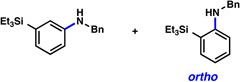

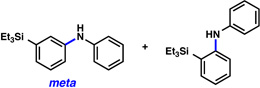

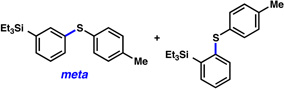

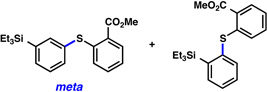

A comparative regioselectivity study was performed, where triethylsilylbenzyne 1 was generated in situ upon treatment of 5 with CsF in acetonitrile, in the presence of a variety of nucleophiles (Table 1).19,20 Upon trapping of the aryne with benzylamine, reaction occurred to give a 1:2 ratio of products favoring ortho substitution (entry 1). However, when aniline was employed, the regioselective preference switched to favor meta addition (entry 2), which is consistent with the observations reported by Akai.10g Other trapping agents that have not been used with silylbenzynes previously were also tested. Thiophenol based reagents also gave products of meta substitution predominantly (entries 3 and 4); in the later case, selectivity was 10:1. An enamine reagent, which functions as a carbon nucleophile, exclusively yielded the meta-substituted product (entry 5). Use of 4-t-Bu-benzoic acid, however, gave 1:3 selectivity, favoring ortho addition (entry 6).

Table 1.

Nucleophilic additions to triethylsilylbenzyne 1a

| entry | trapping agent | product(s) | ratio (yieldb) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H2N–Bn |  |

1:2 (81% yield) |

| 2 |  |

2:1 (99% yield) |

|

| 3 |  |

4:1 (91% yield) |

|

| 4 |  |

|

10:1 (77% yield) |

| 5 |  |

|

(52% yield) |

| 6 |  |

|

1:3 (53% yield) |

See Supporting Information for experimental details.

Yields determined by 1H NMR analysis with external standard.

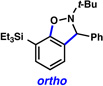

Triethysilylaryne 1 was next evaluated in a series of cycloaddition reactions. As shown in Table 2, the selectivity patterns varied as a function of the trapping agent employed. A nitrone cycloaddition gave a 73% yield of a single regioisomer of product (entry 1), suggestive of ortho attack, as seen in previous nitrone cycloadditions of silylarynes.10d Trapping of the silylaryne with pyridine N-oxide21 also proceeded with a significant preference for ortho addition (entry 2). Conversely, cycloaddition with a diazoester22 exclusively afforded the product resulting from initial meta attack (entry 3). Reaction with benzyl azide23 gave a 6:1 ratio of products, favoring initial meta addition (entry 4). Despite variations in the initial site of nucleophilic attack, the major regioisomer observed in each cycloaddition is presumably that which arises from the least sterically encumbered transition state.

Table 2.

Cycloaddition reactions with triethylsilylbenzyne 1a

| entry | trapping agent | product(s) | ratio (yieldb) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

(73% yield) | |

| 2 |  |

1:9 (60% yield) |

|

| 3 |  |

(65% yield) | |

| 4 | N3–Bn |  |

6:1 (85% yield) |

See Supporting Information for experimental details.

Yields determined by 1H NMR analysis with external standard.

These results demonstrate that nucleophilic additions and cycloadditions of 3-triethylsilylbenzyne do occur with significant regioselectivities, but the orientation of attack varies as a function of the trapping agent. DFT calculations were carried out to provide additional insights into the origins of these observations. All geometry optimizations were performed using Gaussian 0924 using the B3LYP density functional and the 6-311+g(d,p) basis set. A frequency calculation was performed on all reactants and transition states to verify minima and first order saddle points, respectively, and an ultra fine grid was used for all numerical integration. Unscaled zero-point energies were used, and Truhlar’s anharmonic correction was applied to frequencies that are less than 100 cm−1.25 Trimethylsilylbenzene was used as a model for triethylsilylbenzyne.26

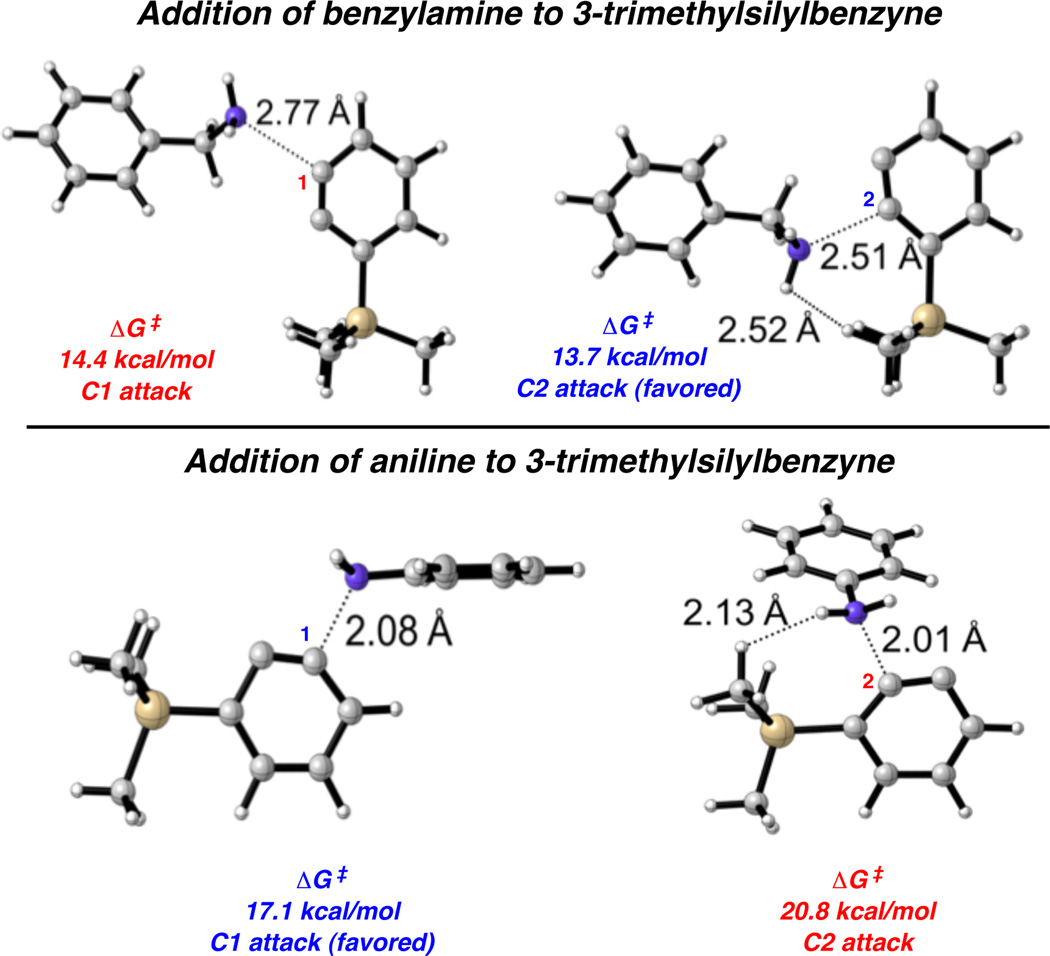

Figure 2 shows optimized transition states for the nucleophilic additions of benzylamine and aniline to 3-trimethylsilylbenzyne. The barrier for attack of benzylamine at C2 is predicted to be 0.7 kcal/mol lower than for attack at C1. Addition at C2 is favored because the aryne’s pre-distorted bond angles favor nucleophilic attack at the flatter, more electrophilic carbon, which is C2 in this case. During the attack, the aryne has to undergo geometric changes, including an increase of the CCC angle at the site of attack and compression of the other terminus of the aryne. The larger angle, like C2 in triethylsilylbenzyne, will be attacked preferentially. In contrast, for aniline, attack is predicted to be favored at C1 rather than C2 by 3.7 kcal/mol. Because aniline is a more bulky nucleophile, it suffers from more steric hindrance with the silyl group of the benzyne. As shown in Figure 2, the H–H distance of the two closest hydrogens in the C2 attack of aniline are very close at 2.13 Å. In the case of benzylamine the closest H–H distance is 2.52 Å. This steric interaction is overriding the aryne distortion preference for attack at C2. Although the magnitude of selectivity is exaggerated, computations correctly predict experimental regioselectivities.27

Figure 2.

Transition states for nucleophilic additions of benzylamine and aniline to 3-trimethylsilylbenzyne.

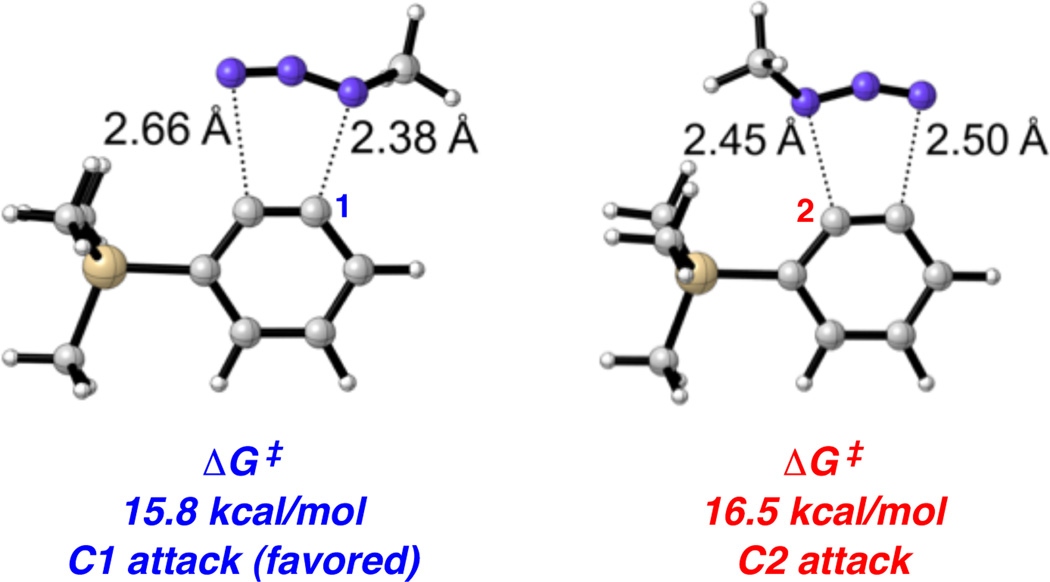

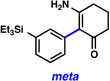

The cycloaddition of methylazide with 3-trimethylsilylbenzyne was also examined computationally, with methylazide serving as a model for benzylazide. Transition states are shown in Figure 3. C1 attack is favored, which is consistent with experimental results, by 0.7 kcal/mol. Aryne distortion would favor attack of the nucleophilic substituted terminus at C2, but steric hindrance overrides this electronic preference leading to preferential attack at C1.

Figure 3.

Cycloaddition of methylazide with 3-trimethylsilylbenzyne.

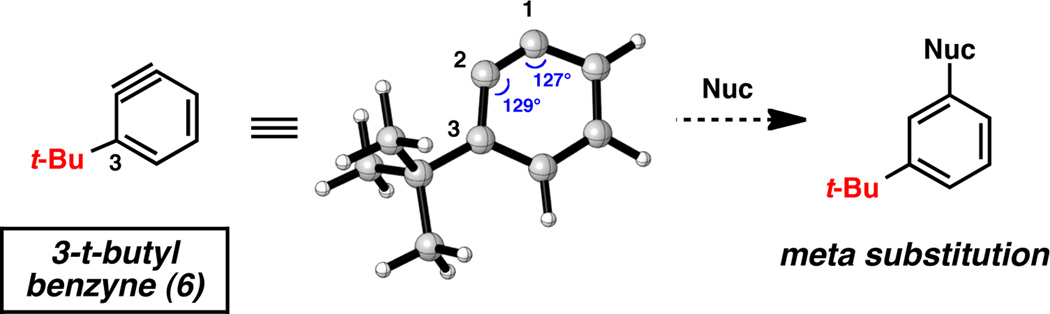

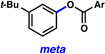

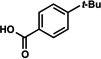

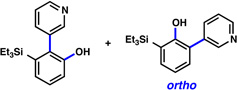

For comparison, we studied 3-t-butylbenzyne (6),28 which is sterically similar to 3-triethylsilylbenzyne (1), but varies electronically (Figure 4). The geometry optimized structure of 6 (B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p)) revealed internal angles of 129° and 127° at C2 and C1, respectively. Given the minimal distortion present, 6 was predicted to undergo sterically-guided attack at C1 to give meta-substituted products.

Figure 4.

Geometry optimized structure of 3-t-butylbenzyne 6 and predicted regioselectivity.

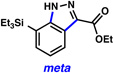

A silyltriflate precursor to aryne 6 was prepared from o-t-Bu-phenol and examined in nucleophilic addition reactions (Table 3).29 When aniline was used as the trapping agent, formation of the meta-substituted product was preferred (entry 1), similar to the trend observed in the reaction of 3-triethylsilylbenzyne. Benzylamine and 4-t-Bu-benzoic acid were also tested with aryne 6. In contrast to the outcome seen in reactions of 1, only meta substitution was observed (entries 2 and 3). These results support the notion that aryne distortion plays a significant role in reactions of 3-silylaryne 1. Quantum chemical calculations were performed for the reaction of 6 with aniline and benzylamine, and in both cases the attack at C1 was strongly favored.29

Table 3.

Nucleophilic additions to t-butylbenzyne 6a

See Supporting Information for experimental details.

ortho-Substituted products were not observed.

Yields determined by 1H NMR analysis with external standard.

The effects of the inductively donating silyl group on arynes have been studied both experimentally and computationally. It has been shown that if the incoming nucleophile is not bulky, the aryne distortion model holds true and the flatter terminus of the aryne is the site of attack. If however, there is sufficient steric bulk on the nucleophile, then attack on the more accessible carbon of the aryne is favored. When the substituent adjacent to the aryne is an alkyl group, steric effects dominate, since there is no significant differential distortion of the aryne bond angles.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are grateful to the NIH-NIGMS (R01 GM090007), Boehringer Ingelheim, DuPont, Eli Lilly, Amgen, AstraZeneca, the Foote Fellowship (S.M.B.), the Stauffer Charitable Trust (S.M.B.) and the University of California, Los Angeles, for financial support. We thank Joshua Melamed (UCLA) for experimental assistance, and Dr. John Greaves (UC Irvine) for mass spectra. We are grateful to the National Science Foundation (CHE-0548209 to K.N.H.) for financial support. Computer time was provided in part by the UCLA Institute for Digital Research and Education (IDRE) and the XSEDE supercomputers Trestles and Gordon at San Diego Supercomputer Center. These studies were supported by shared instrumentation grants from the NSF (CHE-1048804) and the National Center for Research Resources (S10RR025631).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Detailed experimental procedures and compound characterization data (PDF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Contributor Information

K. N. Houk, Email: houk@chem.ucla.edu.

Neil K. Garg, Email: neilgarg@chem.ucla.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Reinecke MG. Tetrahedron. 1982;38:427. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Pellissier H, Santelli M. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:701. [Google Scholar]; b) Wenk HH, Winkler M, Sander W. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:502. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Sanz R. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 2008;40:215. doi: 10.1080/00304940809458083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Chen Y, Larock RC. Arylation Reactions Involving the Formation of Arynes. In: Ackermann L, editor. Modern Arylation Methods. Weinheim: Wiley–VCH; 2009. pp. 401–473. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tadross PM, Stoltz BM. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:3550. doi: 10.1021/cr200478h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Cheong PH-Y, Paton RS, Bronner SM, Im G-Y, Garg NK, Houk KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:1267. doi: 10.1021/ja9098643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Im G-Y, Bronner SM, Goetz AE, Paton RS, Cheong PH-Y, Houk KN, Garg NK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:17933. doi: 10.1021/ja1086485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.For the application of distortion energies to regioselectivity of cycloaddition reactions, see: Ess DH, Houk KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:10646. doi: 10.1021/ja0734086. Ess DH, Houk KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:10187. doi: 10.1021/ja800009z. Lam Y-h, Cheong PH-Y, Blasco Mata JM, Stanway SJ, Gouverneur V, Houk KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:1947. doi: 10.1021/ja8079548. Hayden AE, Houk KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:4084. doi: 10.1021/ja809142x. Schoenebeck F, Ess DH, Jones GO, Houk KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:8121. doi: 10.1021/ja9003624. For the application of distortion energies to regioselectivity of palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, see: Legault CY, Garcia Y, Merlic CA, Houk KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12664. doi: 10.1021/ja075785o. Garcia Y, Schoenebeck F, Legault CY, Merlic CA, Houk KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:6632. doi: 10.1021/ja9004927. For a discussion of activation strain theory, see: van Zeist W-J, Bickelhaupt FM. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010;8:3118. doi: 10.1039/b926828f. For a discussion of the application of distortion/interaction theory to stereoselectivity, see: Kolakowski RV, Williams LJ. Nat. Chem. 2010;2:303. doi: 10.1038/nchem.577.

- 6.Bronner SM, Goetz AE, Garg NK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:3832. doi: 10.1021/ja200437g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.3-Alkoxyarynes are known to react regioselectively. For pertinent reviews, see reference 2. For a recent example of alkoxybenzynes undergoing regioselective reactions, see: Tadross PM, Gilmore CD, Bugga P, Virgil SC, Stoltz BM. Org. Lett. 2010;12:1224. doi: 10.1021/ol1000796. see also references therein.

- 8.3-Haloarynes react in a similar sense; for examples, see reference 6 and the following: Biehl ER, Nieh E, Hsu KC. J. Org. Chem. 1969;34:3595. Moreau–Hochu MF. Tetrahedron. 1977;33:955. Ghosh T, Hart H. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:3555. Hart H, Ghosh T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:881. Wickham PP, Reuter KH, Senanyake D, Guo H, Zalesky M, Scott WJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:7521. Gokhale A, Scheiss R. Helv. Chem. Acta. 1998;81:251.

- 9.The formation of meta-substituted products is also favorable because of steric considerations.

- 10.For the addition of organolithium species to silylarynes (meta preferred), see: Heiss C, Cottet F, Schlosser M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005:5236. Heiss C, Cottet F, Schlosser M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005:5242. Diemer V, Begaud M, Leroux FR, Colobert F. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011:341. For nitrone or furan Diels–Alder cycloadditions involving silylarynes (initial ortho preferred addition), see: Matsumoto T, Sohma T, Hatazaki S, Suzuki K. Synlett. 1993:843. Akai S, Ikawa T, Takayanagi S-i, Morikawa Y, Mohri S, Tsubakiyama M, Egi M, Wada Y, Kita Y. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:7673. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803011. Dai M, Wang Z, Danishefsky SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:6613. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.09.019. For the addition of amine nucleophiles to silylarynes, see: Ikawa T, Nishiyama T, Shigeta T, Mohri S, Morita S, Takayanagi S-i, Terauchi Y, Morikawa Y, Takagi A, Ishikawa Y, Fujii S, Kita Y, Akai S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:5674. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100360.

- 11.The trimethylsilyl derivative was studied initially, but competitive product desilylation complicated regioselectivity analysis.

- 12.For ring-fused arynes or those that possess inductively withdrawing groups, angle differences of >4 degrees between the two aryne termini generally give synthetically useful regioselectivities, regardless of the trapping agent employed.

- 13.The ortho-selectivity for the addition of amines has previously been rationalized by the presumed formation of a pentavalent fluorosilicate, which in turn, perturbs the aryne electronically; see ref 10g.

- 14.For Kobayashi’s approach to arynes, see: Himeshima Y, Sonoda T, Kobayashi H. Chem. Lett. 1983:1211.

- 15.Booker JEM, Boto A, Churchill GH, Green CP, Ling M, Meek G, Prabhakaran J, Sinclair D, Blake AJ, Pattenden G. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006;4:4193. doi: 10.1039/b609604b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Díaz M, Cobas A, Guitián E, Castedo L. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2001:4543. Also see reference 9g.

- 17. Peterson EA, Jacobsen EN. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:6328. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902420. Also see reference 9g.

- 18.Shimizu M, Mochida K, Hiyama T. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:9760. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Z, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:3198. doi: 10.1021/jo0602221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramtohul YK, Chartrand A. Org. Lett. 2007;9:1029. doi: 10.1021/ol063057k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raminelli C, Liu Z, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:4689. doi: 10.1021/jo060523a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Z, Shi F, Martinez PDG, Raminelli C, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:219. doi: 10.1021/jo702062n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.a) Shi F, Waldo JP, Chen Y, Larock RC. Org. Lett. 2008;10:2409. doi: 10.1021/ol800675u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Campbell-Verduyn L, Elsinga PH, Mirfeizi L, Dierckx RA, Feringa BL. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:3461. doi: 10.1039/b812403e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frisch MJ, et al. Gaussian 09, revision C.01. Wallingford, CT: Gaussian, Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ribeiro RF, Marenich AV, Cramer CJ, Truhlar DG. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:14556. doi: 10.1021/jp205508z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.See the SI for comparison of aniline attack at either C1 or C2 3-trimethylsilylbenzyne and 3-triethylsilylbenzyne.

- 27.This observation is consistent with previous studies of the aryne distortion model; see reference 4a for discussion.

- 28.3,5-di-t-Butylbenzyne has been studied in a nitrone cycloaddition (see reference 10d). For other studies involving 6 (or substituted derivatives), see: Franck RW, Leser EG. J. Org. Chem. 1970;35:3932. Yamamoto G, Koseki A, Sugita J, Mochida H, Minoura M. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2006;79:1585. Cadogan JIG, Cook J, Harger MJP, Hibbert PG, Sharp JT. J. Chem. Soc. B. 1971:595. Franck RW, Yanagi K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968;90:5814.

- 29.See the Supporting Information.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.