Abstract

A variety of genetic and molecular alterations underlie the development and progression of colorectal neoplasia (CRN). Most of these cancers arise sporadically due to multiple somatic mutations and genetic instability. Genetic instability includes chromosomal instability (CIN) and microsatellite instability (MSI), which is observed in most hereditary non-polyposis colon cancers (HNPCCs) and accounts for a small proportion of sporadic CRN. Although many biomarkers have been used in the diagnosis and prediction of the clinical outcomes of CRNs, no single marker has established value. New markers and genes associated with the development and progression of CRNs are being discovered at an accelerated rate. CRN is a heterogeneous disease, especially with respect to the anatomic location of the tumor, race/ethnicity differences, and genetic and dietary interactions that influence its development and progression and act as confounders. Hence, efforts related to biomarker discovery should focus on identification of individual differences based on tumor stage, tumor anatomic location, and race/ethnicity; on the discovery of molecules (genes, mRNA transcripts, and proteins) relevant to these differences; and on development of therapeutic approaches to target these molecules in developing personalized medicine. Such strategies have the potential of reducing the personal and socio-economic burden of CRNs. Here, we systematically review molecular and other pathologic features as they relate to the development, early detection, diagnosis, prognosis, progression, and prevention of CRNs, especially colorectal cancers (CRCs).

Keywords: Early detection, molecular diagnosis, prognosis, molecular staging, colorectal cancer

1. Introduction

Colorectal neoplasias (CRNs) are a major medical concern worldwide, and they have a substantial impact on the costs of healthcare. In particular, colorectal adenocarcinomas (CRCs) are responsible for considerable morbidity and mortality. In the United States (US) in 2009, there were an estimated 146,970 new cases and 49,980 deaths from CRCs [1]. They are the second leading cause of cancer deaths in the US. The disease is heterogeneous, especially with respect to the anatomic location of the tumor, and there are racial differences and genetic and dietary interactions that influence its development. The colon accounts for 70% of large intestinal cancer. Approximately 95% of CRCs are believed to have evolved from adenomatous polyps. CRCs arising de novo from the epithelium are only 5% of the total. A variety of genetic and molecular changes occur as these polyps transform from benignity to malignancy [2].

Colonoscopy has allowed a change in CRC intervention, from one of early detection to one of prevention. It leads to removal of polyps before molecular changes occur and before lesions reach the threshold of malignancy. While the cost of monitoring patients by colonoscopy may seem extensive, it is a fraction of the cost of treating invasive cancer. After diagnosis and treatment, the tumor markers, CEA and Ki-67, can be used to follow these patients in addition to colonoscopy. New markers and genes associated with the development of CRCs are being discovered at an accelerated rate. This article reviews molecular and other pathologic features as they relate to the development, early detection, diagnosis, prognosis, progression, and prevention of CRNs, especially CRCs.

2. Risk factors

Risk factors in colorectal carcinogenesis include a family history of CRNs, development of polyps, inflammatory bowel disease (e.g., ulcerative colitis), obesity, tobacco and alcohol abuse, high stress, and factors associated with the Western diet. Patients who exercise strenuously and take non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs daily have a reduced likelihood of developing CRCs [3,4].

2.1. Dietary factors

Diets high in red and processed meats and refined sugar and low in fruits, vegetables, and fiber are thought to increase the risk for CRCs. Of special concern are the products of pyrolysis (i.e., chemicals resulting from overcooking, especially if they stay with the meat or if the gravy and drippings are consumed). Dietary consumption of starch; calcium; vitamins B, C, D, and E; β-carotene (a precursor of vitamin A); and folate appear to be protective. Nevertheless, there is a general lack of understanding of factors in the diet that cause increased risk or are protective for CRNs; the risk may involve the interaction of dietary components and bile acids with intestinal bacteria, and intestinal mucus with dietary carcinogens [5–7]. There is the contention that dietary fiber decreases transit time in the intestine, thus minimizing long-term contact between the dietary carcinogens and the intestinal mucosa [8]. Multiple dietary components acting concomitantly may be required for the development of CRNs.

2.2. Chronic inflammation

Chronic inflammation of the colorectum, similar to that in ulcerative colitis, is a risk factor for CRC. Grizzle et al. [382] have proposed that such tumors are the results of longstanding, continuous damage, inflammation, and repair (LOCDIR). The concept is that LOCDIR changes cellular features of the epithelium, causing loss of cellular differentiation (loss of cellular mucus) and development of cellular atypia and mutations at multiple sites. DNA damage, with microsatellite instability (MSI) and genomic instability, may arise within a year. Kruppel-like Factor 6 (KLF-6) is frequently inactivated in CRC [9]. As cellular atypia increase, there may be progress from low- to high-grade dysplasia. After 10 or more years, carcinomas may develop without an exophytic feature. After 10 years of ulcerative colitis, the risk of colon cancer is 20 to 30 times that for a matched population. As an effective preventive measure, most patients with ulcerative colitis undergo total colectomy with ileostomy. A more controversial but also effective procedure is proctocolectomy with distal rectal mucosectomy. Although Crohn’s disease had long been thought to have no association with the development of CRCs, it is now known that there is an 8% risk of developing CRC over a 20-year period [10]. The problem of chronic inflammation with healing and epithelial changes at the cellular and molecular levels may be involved, since most of these cancers occur in the strictured areas of the intestines.

2.3. Environmental exposures

Environmental exposures have various effects on the development of CRNs, depending upon the individual’s metabolic enzymes that are involved in detoxification of carcinogens or activation of procarcinogens. For example, individuals with the E487K polymorphism of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) have reduced ALDH2 activity. Alcohol consumption is of greater risk for individuals heterozygous for ALDH2 [11]. Similarly, 5,10-methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphisms coupled with low folate levels increase the risk of CRC development associated with alcohol consumption [12–14]. Also, polymorphisms in L-arylamine-N-acetyltransferase, cytosolic glutathione S-transferase, and cystathionine β-synthase increase the risk of cancer, and, in some cases, the age at onset of CRCs [15, 16].

3. CRC Models, hereditary and sporadic

3.1. Hereditary CRNs

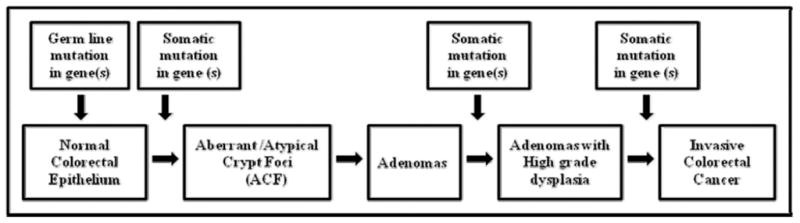

Most CRCs are sporadic; fewer than 5% are familial. There are two recognized familial forms of CRNs. These involve the inheritance of a single copy of a mutated gene, APC, which causes the development of familial adenomatous polyposis [17] or one mutated copy of a mismatch repair gene, such as MSH2 or MLH-1, which causes hereditary nonpolyposis CRC (HNPCC) with MSI [18–20]. Cowden disease (an autosomal dominant hamartomatous syndrome often associated with breast cancers, thyroid disease, trichlemmomas, and gastrointestinal polyps and cancers) does not appear to be a strong contributor to familial forms of CRNs. The general development of these forms of hereditary CRCs is illustrated in Fig. 1. Various mutations in APC also cause familial CRCs in the Gardner syndrome (epidermal inclusion cysts, bone osteomas, and colonic polyps), attenuated adenomatous polypoposis coli, and the Turcot syndrome [21–23]. Other familial forms of CRC occur in MU-TYH (MYH)-associated polyposis (mutations in MU-TYH [24]); juvenile polyposis syndrome (mutations in SMAD4, BMPR1a or PTEN) [25,26]; the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) [27]; and CRNs associated with glioblastoma multiforme (mutations in multiple pathways, including p53 and PMS2) [28]. Thus, development of CRNs is frequently associated with mutations/methylations or dysregulation of the following genes: APC, MSH2, MLH1, PMS1, PMS2, MSH6, PTEN, SMAD4, MUTYH (MYH), BMPR1α, LKB1/STK11, and B-RAF. The progression of CRNs, as will be discussed, is associated with mutations or dysregulation of DCC, K-ras, Bcl2, and p53.

Fig. 1.

The general development of hereditary CRCs.

3.2. Sporadic CRNs

The model presented by Fearon and Vogelstein has been the paradigm of the genetic alterations involved in development of CRCs [2]. The pattern of CRC development, as exhibited in FAP, is the best model for the development of most common cases of sporadic CRCs; however, the order and pattern of development of mutations are more variable in sporadic cases. Most sporadic CRCs develop due to multiple somatic mutations and genetic instability, which are broadly grouped into the category of chromosomal instability (CIN); a smaller proportion follows the MSI observed in most HNPCCs.

Epigenetic changes secondary to hypermethylation of CpG islands of the promoters of mismatch repair genes, especially hypermethylation leading to the inactivation of both copies of hMLH1, are thought to cause sporadic tumors with MSI. This is consistent with the high rate of MSI (up to 15%) observed in sporadic CRCs. Other genes confer a risk for the development of CRC. The transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) signal transduction pathway is thought to be important in the development of multiple types of cancer. In HNPCC, MSI frequently knocks out functioning TGFβR2 [29]. Similarly, a polymorphic allele of TGFβR1 (TGFβR1*6A) has an increased frequency in patients with CRC, and germ-line allele-specific expression of TGFβR1 is associated with an increased risk of CRC [30–33].

4. Lesions of CRNs

4.1. Preinvasive neoplasia

CRCs arise primarily from polyps, which are mucosal pedunculated and sessile lesions found on the luminal aspect of the colorectum. Frequently, a polyp component is present at the edge of a CRC. All adenomas have a malignant potential; frequency of transformation increases as histopathological features change in tubular (5%), tubulovillous (22%), and villous (40%) adenomas [34]. There is a significantly higher risk of these polyps containing malignant cells when the size increases to greater than 2 cm.

4.1.1. Aberrant crypt foci (ACF)

Although polyps are thought to arise from ACF, transitional lesions between ACF and polyps have not been described. ACF, first identified by Bird [35–37] in carcinogen-induced CRNs of rodents, represent an early histopathologic change in the development of CRNs. Subsequently, ACF were identified in human colonic mucosa, where the lesions were associated with early cellular mutations in K-ras [37–39]. ACF develop following increased cellular proliferation and cellular accumulation. Some of the histologic and molecular changes of ACF are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Features of aberrant crypt foci

| Histo-morphology | Tumors identified in 25% of animals with associated ACF changes at 20 weeks (A) |

| Increased staining with methylene blue (gross) (A&H) | |

| Increased size of the crypt (A&H) | Enzymatic alterations |

| Tendency to form associated groups of dysplastic glands (A&H) | Hexosamidase decreased (A) or increased (H) |

| Slit-like irregular lumens (A&H) | Increased stromal gamma-glutamyltransferase (A) |

| Development of carcinoma in situ (A&H) | Increased stromal alkaline phosphatase (A) |

| Mucin depletion | Decreased stromal acid phosphatase (A) |

| Decreased mucin (A) | Variable (usually increased) stromal 5′-nucleotidase (A) |

| Increased sialomucins and decreased sulfomucins (A) | |

| Increased PAS reactive material (A) | Mutations/genomic changes |

| K-ras codons 12 & 13 (A&H) | |

| Increased proliferation indices | p53 (uncommon) (A&H) |

| BrdU incorporation (A&H) | APC (H) |

| Mitoses | Increased genomic instability (H) |

| PCNA (A) | |

| ACF in cases with CRC | Molecular changes/increased oncofetal markers |

| Dysplasia identified: 6% severe, 8% moderate 40% mild (H): carcinoma in situ identified (H) | Altered pattern of expression of p21W af–1 |

| Increased expression of CEA (H) |

A = Animal models; H = Humans.

4.1.2. Adenomatous polyps/adenomas

Most polyps develop in the colorectum. About 40% of patients over 50 years of age have at least one colorectal polyp, and the number increases with age [40]. Typically, 65–85% of polyps are tubular, 10–25% tubulovillous, and 5–10% villous. Flat adenomas, which may develop into CRNs, are rare and occur characteristically in families with inheritable CRNs. About 90% of the preinvasive neoplastic lesions of the colorectum are thought to be polyps or polyp precursors, such as ACF. Most tubular polyps are considered to be neoplastic, and are designated as adenomas or adenomatous polyps. Periodic removal of all polyps from the colorectum reduces the development of CRCs [40–42].

In our study of 90 cases of CRCs, along with their contiguous adenomatous components (CAdCs), patients whose CAdCs and contiguous CRCs demonstrated p53 nuclear accumulation (p53nac) had shorter median survival (35.9 months) than those whose CAdCs and CRCs did not (80.56 months). Patients whose CAdCs had p53nac and lacked Bcl-2 expression had a lower median survival (15.74 months) compared to patients whose CAdCs did not demonstrate p53nac but had increased expression of Bcl-2 (71.8 months). These findings suggest that, for adenomas demonstrating p53nac but lacking Bcl-2 expression, their contiguous CRCs are more likely to become aggressive [43].

4.1.3. Other pre-invasive neoplastic lesions of the colorectum

In contrast to adenomatous polyps, hyperplastic polyps, unless they are associated with familial syndromes, have little to no potential to develop into CRNs. Polyps of patients with the hyperplastic polyposis syndrome may harbor foci of epithelial dysplasia, and hence these patients are considered at risk for the development of CRNs. A mixture of epithelial serration and dysplasia occurs in mixed polyps or serrated adenomas, which may be precursors to adenomatous polyps. Serrated adenomas may exhibit mutations in K-ras or BRAF as well as MSI secondary to methylation of hMLH1, while flat adenomas, which may develop into CRNs, are rare and occur characteristically in families with inheritable CRNs.

4.2. Transition from pre-invasive neoplasia to invasive neoplasia

Pre-invasive neoplasias, including carcinoma in situ (high grade dysplasia) do not metastasize. After a tumor reaches 2 mm in size, it requires vascularization to survive. Through angiogenesis, capillaries develop in the tumor, and when malignancy develops, cells can enter the circulation for microinvasion. As microinvasion begins, typically in adenomas, metastasis remains unlikely, either because of the limited number of neoplastic cells exposed to lymphatic channels and the reduced number of lymphatic channels present in the colorectal mucosa or lamina propria or because the volume of malignant cells is small. In the colorectal mucosa, lymphatics are found only at the base of the mucosa, immediately above the muscularis mucosa. Some capillaries, however, are in the lamina propria. Until there is invasion through the muscularis mucosa, the tumor is a Tis component in the TNM staging system (Stage 0); when the tumor invades through the muscularis mucosa, it becomes T1 (also Stage I). Invasion into the muscularis propria without metastases leads to T2 lesions, and invasion without metastasis across the muscularis propria to the serosa results in T3 lesions (Stage IIA). Invasion, without metastasis, that perforates the serosa (visceral peritoneum) results in T4 or Stage IIB lesions. Of note, Stage I and II lesions may be cured by surgery.

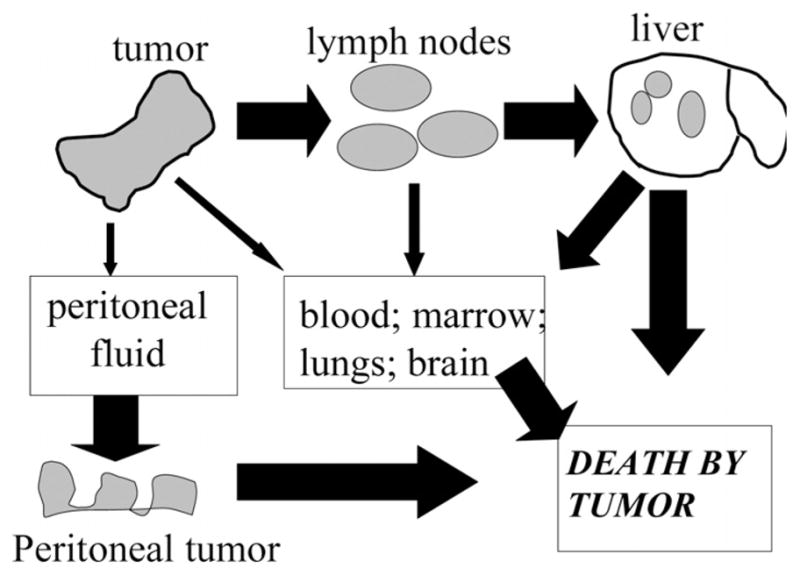

Why do metastases not occur until tumors are larger? Perhaps they appear more frequently as CRCs increase in size due to interaction of cancer cells with greater numbers of lymphatics and blood vessels. This would lead to a greater likelihood of metastatic spread to local lymph nodes (Stage III) and then to distant metastases (Stage IV) (Fig. 2). However, per ‘size category,’ HNPCCs are less aggressive than FAP lesions or sporadic CRCs. Alternatively, metastatic spread could be facilitated by metastasis-inducing genes, such as osteopontin, MEK1, and CXCR4 [44]. The main genes that affect metastatic spread, however, typically inhibit the process, as reviewed by Stafford et al. [45]. These genes can be grouped based on their location: membrane-bound, cytoplasmic, or nuclear. Further, some microRNAs (e.g., miR-146) may suppress the metastatic spread of breast cancer [46].

Fig. 2.

Pathways by which CRCs cause death. *The size of the arrow is proportional to the likelihood of the pathway.

An alternative to accepted patterns of metastases and growth in general is the hypothesis of self-seeding, developed by Norton and colleagues [47]. According to this concept, cells from non-metastatic tumors circulate in blood/lymph fluid and return to the peripheral area of the primary tumor, seeding its periphery. When the surface area of the primary tumor and its volume reach a critical level, the tumor cells no longer completely return to the primary tumor, and metastases occur. Further, when the primary tumor is surgically removed, seeding of the tumor by the circulating cells can no longer occur, leading to metastases; however, neoadjuvant therapy may reduce metastatic spread [48, 49].

4.3. Invasive neoplasia

4.3.1. Distribution of neoplasia in the colorectum

CRC is a heterogeneous disease, especially with respect to the anatomic location of the tumor. Based on the embryologic development of these areas from the midgut (the proximal colon) and hindgut (the distal colorectum), the colorectum can be divided into the proximal colon (cecum, ascending colon, and proximal 2/3 of the transverse colon), distal colon (1/3 of transverse colon at the splenic flexure, descending colon, and sigmoid colon), and the rectum [50]. There are anatomic, functional, and molecular differences between the proximal and distal colorectum, including differences in the phenotypic expression of various biomarkers [51]. Proximal and distal CRCs often differ in their response to screening tests, the stage at which they are diagnosed, their etiology, and their subsequent effect on mortality [52–63]. Relative to proximal CRCs, distal CRCs have a higher incidence of abnormalities in the p53 gene [56,59–61], more allelic deletions of the 17p gene [54,56,60], and lower rates of MSI [63,64]. Furthermore, the prognostic significance of p53nac is greater for adenocarcinomas of the proximal than the distal colon [65–67]. In contrast, p53nac is significantly associated with a higher incidence of local recurrence in distal but not proximal CRCs [68].

Rectal tumors are considered apart from CRCs. This is because the proximal and distal colons are different embryologically and have dissimilar characteristics (Table 2). The therapeutic approach to these tumors is different from that for colon tumors. Over the last several decades, there has been an apparent shift in the most frequent location of occurrence of colon cancers from the distal to proximal areas of the colon. This may be due to a change in methods of diagnosis, especially with the increased use of colonoscopy, which can detect cancers earlier than barium enemas, used in the past, or sigmoidoscopy, which views only the distal colon and rectum. The first column of Table 3 shows the distribution of colon and rectal adenocarcinomas in the period 1941–1956 [69]. We have noted a shift to more proximal lesions, especially in African-Americans.

Table 2.

Features of proximal versus distal colon versus rectum

| Characteristics | Proximal colon | Distal colon | Rectum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embryological development | Midgut | Hindgut | Hindgut |

| Vascular supply | Superior mesenteric | Inferior mesenteric | Inferior mesenteric |

| Primary function | Fluid transport from lumen; fecal material is liquid | Some fluid transport from lumen plus storage; semisolid fecal material | Fecal storage; feces is solid |

| Primary pattern of mucin | Sulformucins in top 2/3 of crypt; acidic sialomucins in bottom 1/3 of crypts. | N- and O-acetylated sialomucins in superficial epithelial cells and top portion of crypt; sulfomucins at base of crypts. | N- and O-acetylated sialo- mucins in superficial epithelial cells and top portion of crypt; sulfomucins at base of crypts. |

| Blood group expression | Appropriate expression of A, B, H and Leb blood groups | No expression of appropriate A, B, H, and Leb blood groups | No expression of appropriate A, B, H, and Leb blood groups |

| Location of CRC with micro- satellite instability, i.e. hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer | Usual location of MSI tumors | MSI tumors much less frequent | Infrequent |

| Aberrant crypt foci associated with CRC | 50% of cases | 100% of cases | 100% of cases |

| Pattern of mucin of tumors | O-acetylated sialomucins not increased | O-acetylated sialomucins increased | O-acetylated sialomucins increased |

| K-ras mutations in tumors | Less common | More common | More common |

| p53 mutations – nuclear accumulation | Less common than distal | Majority of distal tumors | More common |

| Risk of cancer development secondary to polymorphic enzymes of cytosolic glutathione S-transferase | Increased | Not increased | Not increased |

Table 3.

Distribution of CRCs based on patient ethnicity and tumor location at UAB

| Location | Copeland et al. [69]. % | UAB Caucasian- American % | UAB African- American % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cecum | 5.2 | 22.7 | 21.8 |

| Ascending | 5.3 | 16.9 | 12.8 |

| Transverse | 8.4 | 8.5 | 8.2 |

| Descending | 6.9 | 15.7 | 7.1 |

| Sigmoid | 30.8 | 22.5 | 23.9 |

| Rectum | 39.8 | 13.6 | 26.1 |

| Proximal colon – all components | 18.9 | 48.2 | 42.8 |

| Distal colon – all components | 41.3 | 38.2 | 31.0 |

4.3.2. Racial and sexual differences in CRCs

Based on SEER results, both colorectal incidence and mortality are higher in African-Americans than Caucasian-Americans and other racial ethnic groups (Tables 3 and 4) [1,70]. In all racial/ethnic groups, males have a higher incidence and mortality. Over the last decade, incidence and mortality rates for CRCs in males have declined in every racial/ethnic group of interest. For females, the incidence over the last decade has decreased in African-Americans, Caucasian-Americans, and Asian Americans; mortality has decreased for all racial and ethnic groups [1, 70].

Table 4.

CRC incidence and mortality rates, 2001–2005 (1, 12, 13)

| RACE/ETHNICITY | INCIDENCE*

|

MORTALITY*

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| African-American | 71.2 | 54.5 | 31.8 | 22.4 |

| Caucasian-American | 58.9 | 43.2 | 22.1 | 15.3 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 47.3 | 32.8 | 16.5 | 10.8 |

| Asian American/Pacific | 48 | 35.4 | 14.4 | 10.2 |

| American Indian/Alaska | 46 | 41.2 | 20.5 | 14.2 |

| Native | ||||

| Overall** | 59.2 | 43.8 | 22.7 | 15.9 |

Based on cases per 100,000 population.

A variety of reasons have been proposed for the racial disparity in survival differences between African-American and Caucasian-American patients, reviewed in Alexander et al. [52]. These include differences in age, advanced stage at diagnosis, treatment differences, socioeconomic factors, access to health care, biologic differences, and approaches to analysis [71,72]. Recent studies shed light on disparities in access to care and on the molecular characteristics of CRCs in different patient populations, especially African-Americans as compared to non-Hispanic, Caucasian-American patients. This new information will help guide future clinical research and could aid in reducing the difference in cancer outcomes.

There are racial differences in the anatomic locations of primary CRCs [55,73]. African-Americans have an almost equal distribution of adenocarcinomas in the proximal and distal colorectum, but, for Caucasians, distal tumors predominate [74]. In our study of racial differences in post-surgical survival [52], there were poorer 5-year (p = 0.01) and 10-year (p = 0.02) survivals for African-Americans than for Caucasian-Americans with CRCs; however, there were no appreciable differences between African-Americans and Caucasian-Americans with regard to age (p = 0.47), hospital treatment modality (p = 0.37), tumor stage (p = 0.77), or tumor grade (p = 0.17). The only statistical difference between Caucasian-Americans and African-Americans was the anatomic site (p = 0.05), with African-Americans having primarily proximal colon tumors and Caucasian-Americans having primarily distal tumors. Similar outcome differences were observed at 5 years and 10 years, accounting for overall survival with hazard ratios of 1.67 (95% CI 1.21–2.33) and 1.52 (95% CI, 1.12–2.07), respectively. With respect to 5- and 10-year survivals, African-Americans with Stage II disease had hazard ratios of 2.53 (95% CI, 1.31–4.86) and 1.82 (95% CI, 1.04–3.18), respectively.

Our study of post-surgical survival suggests that poorer survival is based upon the biology of the lesion. In our separate study on patients drawn from different institutions, however, medical treatment provided and stage at diagnosis were associated with differences in outcome between Caucasian-Americans and African-Americans; the differences were eliminated for patients treated by the Department of Veterans Affairs [75]. Of note, Caucasian-Americans present with a greater proportion of tumors at local and regional stages [76].

Our studies indicate that there may be biologic differences between CRCs arising in African-Americans and those in Caucasians. Our studies have established that p53nac detected by immunohistochemistry (IHC) is a stronger prognostic biomarker for proximal CRCs in Caucasians than in African-Americans [66,77]. In contrast, high-grade CRCs lead to a shorter time of survival for African-Americans than for Caucasian-Americans [78]. As we recently reported, the incidence of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at codon 72 of the p53 gene was higher in African-Americans than in Caucasian-Americans, and the proline/proline phenotypes of p53 contributed to aggressive progression of CRCs in African-Americans [79]. This polymorphism (proline/proline) has a greater effect on stability of p53 in African-Americans than in Caucasian-Americans, leads to higher grade tumors in African-Americans, and contributes to aggressive progression of CRC [79].

A practical problem is that variations of biomarkers with race and anatomic location of the tumor affect the numbers of specimens that must be studied for validation of molecular markers. For example, in the US, racial and ethnic differences require, at a minimum, population studies of Caucasian-American, African-American, Native American, Asian-Indian subcontinent, Asian-Chinese/Japanese/other, and Hispanic sub-populations. Similarly, because of differing dietary requirements, religious subgroups may require separate studies, as do groups with relatively uniform genetic patterns (e.g., Ashkenazi Jews in the study of breast or ovarian cancers).

5. Prognostic molecular markers

Although the molecular phenotypes of early lesions of hereditary CRNs have been described as derived from either the suppressor gene pathway of FAP or a mutator phenotype causing MSI, few advances have been made in the phenotypic description of sporadic CRCs, especially the molecular changes involved in the invasive stages of these lesions. Our goal has been to identify reliable molecular information that can be used to predict the clinical outcomes of CRCs. Specifically, we aim to characterize the components of molecular phenotypes of CRCs that identify aggressive subtypes. Our laboratory has described phenotypic molecular patterns of invasive CRNs that correlate with clinical outcomes.

Early discovery of CRCs has relied on the relatively insensitive and non-specific detection of occult blood or blood products in the stool or on the expensive and invasive method of endoscopy. However, the detection in stools of atypical molecules, such as mutated p53 or K-ras, of oncofetal proteins, viz., carcinoembryologic antigen (CEA), or of long DNA, may be more specific. The sensitivity and specificity of such methods of molecular detection may be improved by measuring multiple molecular markers of colorectal epithelial cells, which can be obtained from feces.

Traditional clinical counseling of patients and their families and therapeutic decisions have been based upon the pathologic and/or clinical stages of CRCs. In the future, however, the molecular phenotypes of CRCs may be used to determine the ‘molecular stage’ of CRCs and thus aid in counseling and therapeutic decisions, especially if adjuvant therapy is to be used for subgroups of Stage I, II, or III lesions [80].

Various molecular phenotypes are associated with aggressive subtypes of CRCs, including molecular markers that are independent of pathologic stage. These include nuclear accumulation of p53 (p53nac), as identified by IHC; and the phenotypic expression of Bcl-2, MUC-1 (mucin core protein), or p27kip–1, a cell cycle inhibitor.

5.1. Nuclear accumulation of p53 (p53nac)

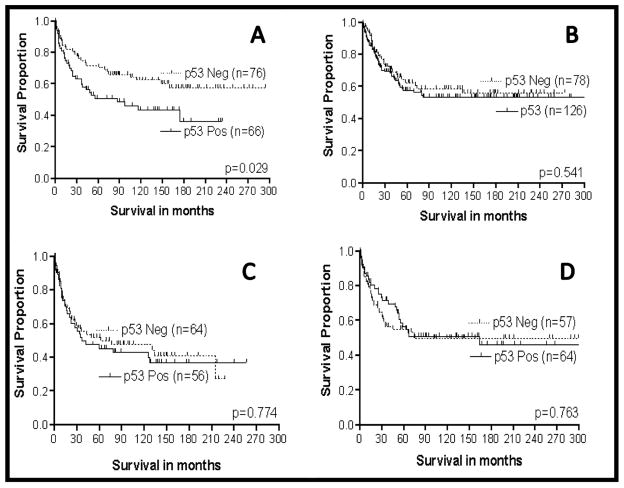

As determined by our methods of IHC, CRCs with cells demonstrating p53nac typically have single-point mutations in p53, as determined by sequencing the complete p53 gene or analysis by single-strand conformation polymorphism [81,82]. In our initial studies, we reported that, in our overall patient population, p53nac was associated with a poor prognosis; however, on subsequent evaluations, we determined that p53nac was important prognostically, primarily for proximal tumors of Caucasian patients [66] (Fig. 3). The literature, as reviewed by Manne et al. [83], Grizzle et al. [65, 81], and McLeod and Murray [84], is not clear with respect to the prognostic importance of p53 in CRCs. This confusion may have resulted in part because of variations of p53nac in mixed populations, including differences in race and anatomic location of tumors, as well as by the methods used for analysis and evaluation. The method of analysis of p53 is especially important, since different points of cut-off in evaluations may vary, depending upon whether or not antigen recovery is accomplished prior to staining [65,66,81,82, 84,85].

Fig. 3.

Survival analysis of Caucasian (N = 346) and African-American patients (N = 241) with CRCs based on p53nac and tumor location. A = Caucasians (N = 142) with proximal CRCs; B = Caucasians (N = 204) with distal CRCs; C = African-Americans (N = 120) with proximal CRCs; D = African-Americans (N = 121) with distal CRCs.

5.1.1. p53 mutations

For patients in geographic and/or ethnic/racial populations, there are differences in the incidence of p53 abnormalities in CRCs. For example, the p53 mutational spectrum of CRCs is different in Japanese patients compared to patients in the US, i.e., the mutation pattern at specific hot spots in the p53 gene varies with populations. C:G to T:A transitions at CpG sites are predominant in US patients, but are less common in Japanese patients [86]. Similarly, there are racial/ethnic variations in the hot spots of point mutations. For example, the codon [175] hot spot does not occur in the Finish population, but there is a codon [213] hot spot. In our studies, we found that the incidence of an SNP at codon 72 of the p53 gene is higher in African-American than in Caucasian patients and is associated with higher mortality [79]. Our further analysis indicated that most (79%) proximal CRCs from African-Americans exhibited wild-type p53, whereas proximal CRCs from Caucasians exhibited a higher incidence of point mutations (52%), at ‘hot spot’ codons (175, 245, 248, 249 and 273). These mutations were located in the L3 domain of p53 (codons 245, 248, and 249). Univariate survival analysis of proximal CRCs of Caucasians demonstrated that mutations in the L3 domain of p53 are more lethal than the wild-type p53 [83]. In contrast, in an European population, p53nac in distal tumors is associated with a higher incidence of local recurrence than p53nac in proximal tumors [68].

5.1.2. p53 polymorphisms

In addition to gene mutations, p53 polymorphisms are risk factors for human malignancies, including CRCs [87,88]. To date, only five polymorphisms have been found in the coding region: four in exon 4 at codons 34, 36 [88], 47 [89] and 72 [90], and one in exon 6 at codon 213 [91]. p53 polymorphisms are also found in the intronic regions: two in intron 1 [92,93], one in intron 2 [94], one in intron 3 [95], two in intron 6 [96,97], five in intron 7 [98,99], and one in intron 9 [100]. Of these, only those at codon 72 have been well characterized. The alleles of the polymorphism in codon 72 encode an arginine (CGC, Arg72) and a proline residue (CCC, Pro72). Earlier studies have noted an association between codon 72 polymorphism and risk of CRCs, although the findings were not conclusive [87,101,102]. The polymorphism at codon 72 (CGC to CCC, substitution of an arginine residue with a proline), however, is a risk factor, and tumors exhibiting Pro72 polymorphisms have increased incidences of missense point mutations in the p53 gene [103]. The Arg/Pro polymorphic site is located in a proline-rich region (residues 64–92) of the p53 protein; this region is required for the growth suppression and apoptosis mediated by p53 but not for cell cycle arrest (reviewed in [104]). Indeed, Dumont et al. reported that, compared to Pro72, the Arg72 form of p53 has a 15-fold enhanced capacity to induce apoptosis and that this increase is due to more efficient localization of the Arg72 form to mitochondria than the Pro72 form [105]. In contrast, for the Pro/Pro phenotype, there is an increased capacity for cancer cell proliferation [105] and cancer progression [103].

5.2. Bcl-2

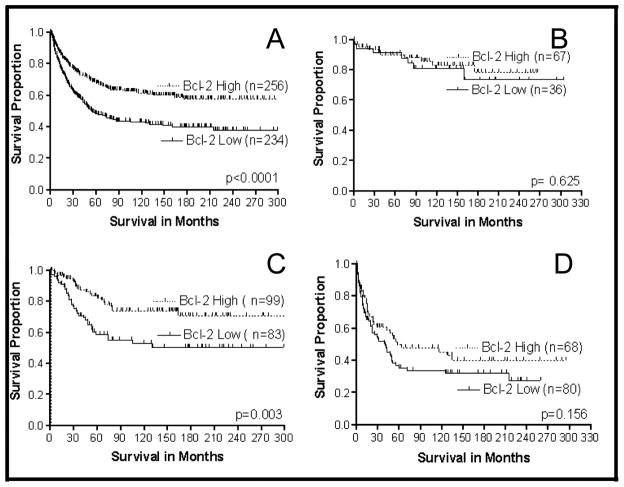

Several oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, such as Bcl-2 and p53, are involved in regulating programmed cell death and cellular proliferation. Dys-regulation and/or alteration of the Bcl-2 and p53 genes occur during the development and progression of CRCs [106–111]. In addition, lack of Bcl-2 expression correlates with local invasion, metastasis, and recurrence [112–114]. Our laboratory initially found, in our complete population, that the phenotypic expression of Bcl-2 was important prognostically and that the combination of p53nac plus Bcl-2 was even more prognostically useful [85]. In a more detailed study with a larger population, we subsequently found that Bcl-2 was important in all CRCs (including Caucasian and African-American populations). The strongest correlation of the expression of Bcl-2 with clinical outcome was primarily for Stage II CRCs (Fig. 4). Our recent studies have demonstrated that Bcl-2 expression status aids in predicting the recurrence [115] and survival of CRC patients, especially in Stage II disease.

Fig. 4.

Survival analysis of CRC patients based on Bcl-2 expression and tumor stage. A = All stages included (N = 490); B = Stage I (N = 103); C = Stage II (N = 182); D = Stage III (N = 148).

Patients with CRCs that exhibit high levels of Bcl-2 expression have been reported to have a good clinical outcome [106,116,117]; however, some studies have not observed such an association [107,112,118,119]. Conversely, for a small group of CRC patients (n = 48), Bhatavdekar et al. [120] correlated high Bcl-2 expression with a poor prognosis. Although the reasons for this controversy (e.g., ethnic/religious and dietary differences) are not known, we hypothesize that the prognostic importance of Bcl-2 expression in CRCs is limited to specific subgroups of patients, similar to the clinical usefulness of p53nac in CRCs, which varies with racial/ethnic groups and with anatomic location of the tumor.

To establish the prognostic usefulness of Bcl-2 in CRCs, we performed a meta-analysis of reported studies on the relationship of Bcl-2 expression and overall survival. We requested original data on all comparable studies from authors who had evaluated the prognostic usefulness of Bcl-2 in predicting overall survival. Some authors, for various reasons, could not supply us with their data. Ultimately, nine studies incorporating a total of 1,989 patients provided either the hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval or information from which the hazard ratio and its variance could be estimated. The meta-analysis indicated that Bcl-2 is a useful prognostic marker for CRCs. The results are outlined in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results of the meta-analysis of lack of Bcl-2 expression and its effect on CRC mortality

| Estimates of effect | Number of studies | Summary HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Studies with adjusted & unadjusted estimates | 9 | 2.62 (1.93, 3.54) |

| Studies with adjusted estimates? | 6 | 1.69 (1.06, 2.32) |

A separate meta-analysis was conducted for studies that reported adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%).

5.3. MUC-1

A characteristic feature of glandular epithelial tissues is synthesis and secretion of mucins, which are large glycoproteins that protect epithelial surfaces. Alterations in mucins with regard to the rate of their production and the extent of their glycosylation have been reported for human malignancies [121], including CRNs [122,123]. Of the various mucin antigens, MUC-1 is best characterized. Higher expression of MUC-1 correlates with increased incidences of regional lymph node and liver metastases [124–126]. Although expression of MUC-1 is associated with aggressiveness of CRCs, its prognostic usefulness in CRNs has not been evaluated adequately. Studies from our laboratory [126] as well as others [124,125] have suggested that increased expression of the core peptide of MUC-1 is associated with a poor prognosis for CRCs.

In an evaluation of the prognostic importance of MUC-1 and MUC-2 for CRCs, we found that the phenotypic expression of MUC-2 was not useful prognostically, but the expressions of MUC-1 and MUC-2 were useful markers in defining the mucinous subtype. In contrast, the phenotypic expression of MUC-1 was important prognostically for CRCs of Caucasians but not of African-Americans [126]. We found no variation in the prognostic importance of MUC-1 based on anatomic location of the tumor [126].

5.4. Proliferation and p27kip–1 expression

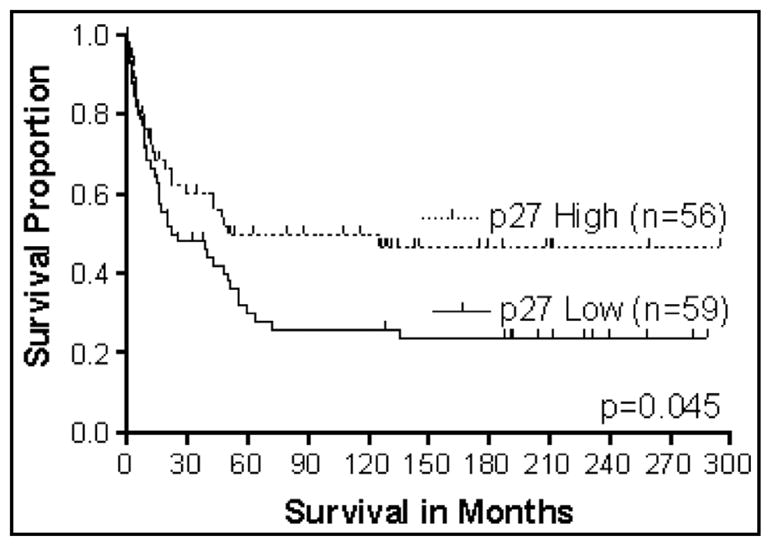

p27kip–1 inhibits the activity of cyclin-dependent kinases (cdks), and, like p21waf–1, prevents progression of cells into the S phase of the cell cycle. Decreased p27kip–1 protein expression is associated with large CRCs, positive lymph nodes, and poor patient survival [127–129]. Furthermore, a small study (n = 41) demonstrated that p27kip–1 is a predictive indicator for tumor metastasis and clinical outcome in right-sided colon tumors [130]. Further studies from our group have suggested that decreased expression of p27kip–1 is an indicator of poor prognosis of patients with Stage III CRCs [131] (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Survival analysis of stage III CRC patients based on p27 expression (N = 115).

We performed a preliminary analysis of the importance of the proliferative index biomarkers, Ki67/MIB-1 and p27kip–1, for CRCs of 48 African-American and 54 Caucasian patients, which had been analyzed previously for p53. In this study, similar proportions of CRCs, collected from African-Americans and Caucasians, exhibited increased expression of p27kip–1 (50% and 54%, respectively) and Ki67 (54% and 50%, respectively). Univariate Kaplan-Meier survival analyses demonstrated that African-Americans with CRCs exhibiting higher expression of p27kip–1 without p53nac had a marginally better overall survival (log rank test, P = 0.055) than any other combination of p27kip–1 and p53nac. In Caucasians, lower expression of p27kip–1 with p53nac demonstrated the lowest probability of overall survival (log rank test, P = 0.011). No prognostic value was found for p27kip–1 or Ki-67 alone or the combinations of Ki-67 with p27kip–1 or p53nac (our unpublished data). Further studies are needed to understand the prognostic importance of p27kip–1 in CRCs based on the anatomic locations of the tumors and patient ethnicity.

5.5. Microsatellite instability (MSI) in CRCs

Mismatch repair deficiency and associated MSI, which are characteristics of HNPCC [18,132] and a subset (~12%) of sporadic CRCs [133,134], can be caused by genes that are either mutated [135] or silenced [136]. Phenotypically, MSI cancers are predominantly right-sided and more likely to be poorly differentiated, mucinous, and larger, and to have a low incidence of metastasis at presentation and a better outcome [137–139].

5.5.1. MSI in CRC and race/ethnicity

The incidence of MSI-High (MSI-H) tumors is 3-fold higher in African-American CRC patients relative to a nonracially selected but serially collected population [140]. Most of these tumors are proximal and well differentiated and have high levels of mucin production [140]. Furthermore, for African-American patients, this higher incidence of MSI correlates with higher incidences of MLH1, MSH2, and BRAF abnormalities [141]. These findings may reflect dietary differences or genetic polymorphisms that may be common in this population. There is also a similar incidence of MSI in CRCs of non-Hispanic Caucasians and in Omani CRC patients, but most of the MSI CRCs are located in the left-side of the colon [142].

5.6. MCC Gene (Mutated in CRCs)

In cases of CRC from FAP, the MCC gene is on chromosome 5q21 in close proximity to the APC gene [143]. It is in the region that frequently exhibits loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in CRCs [144]. The protein encoded by the MCC gene has 829 amino acids and shares a short region of similarity with the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor known to regulate specificity of G protein coupling [143]. Somatic point mutations of MCC were identified in 6 of 90 (15%) sporadic CRCs, but similar mutations were not found in the germ lines of FAP patients ([145]. Also, LOH at the MCC locus or in its vicinity was demonstrated in 22 of 40 (55%) sporadic CRCs [146]. However, for two unrelated patients with FAP, MCC was located outside the deleted regions [147]. Mutations of MCC also have been detected in other neoplasms. The roles of MCC in FAP and/or sporadic CRN are yet to be identified. MCC promoter methylation is a frequent early event in a subset of CRCs and precursor lesions associated with the serrated CRC pathway. MCC is a nuclear, β-catenin-interacting protein that can act as a tumor suppressor in the serrated CRC pathway by inhibiting Wnt/β-catenin signal transduction [148].

5.7. DCC Gene (Deleted in CRCs)

Although Fearon et al. [149] identified the DCC tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 18q, earlier studies implicated LOH in chromosome 18q in the development of sporadic [150] and familial CRCs [151,152]. The protein product of the DCC gene (about 180kD) has structural homologies with neural adhesion protein (NCAM). Most human tissues express the DCC protein at low levels; however, there is higher expression in the brain and normal colorectal epithelium [149,153]. The frequency of allelic loss of 18q is higher in larger adenomas (50%) and primary CRCs (70%) [150,154] than in small and mildly to moderately dysplastic adenomas ([155]. The DCC protein may be involved in cell adhesion, in invasion of CRC cells [149], and/or in terminal differentiation. Allelic loss of the DCC locus is higher in primary CRCs of patients with liver metastasis (95%) than in patients without liver metastasis (40%) [156], suggesting that, in CRCs, allelic loss of DCC is associated with the acquisition of metastatic capacity.

Similarly, expression of DCC mRNA is less in CRCs than in adenomas, indicating that inactivation of the DCC gene is associated with the progression of colorectal tumors [149,157,151–159]. The transmembrane location of the DCC protein is consistent with its involvement in cell-cell and cell-substratum interactions and in the regulation of cell growth and metastasis [149,156, 160]. Based on results with murine models, however, others have questioned involvement of the DCC gene in cell growth, differentiation, morphogenesis, and/or tumorigenesis [161] as well as its involvement in the pathogenesis of CRCs in humans [162].

In CRCs, there are point mutations in the DCC gene [163]. Direct evidence to support its function as a tumor suppressor, however, has come from a study with nude mouse, which demonstrated suppression of the malignant phenotype of xenografts of transformed human keratinocytes by restoration of DCC expression [164]. The tumorigenicity of human CRC cells is suppressed by introduction of a normal copy of chromosome 18q [165], but not by the transfer of a normal copy of the DCC gene. Furthermore, in neuronal cells, the DCC gene is involved in the regulation of cell migration and differentiation [166–168].

Descriptions of the intensity of immunostaining for the DCC protein in human neoplastic tissues have not been consistent [169–171]. Use of an antigen retrieval technique, however, enhances detection of the DCC protein in archival tissues of CRCs and shows that expression of the DCC protein is usually an “all-or-none” phenomenon, with a granular cytoplasmic pattern that is homogeneous throughout the tumor [172]. The cells of the crypts and of the luminal surface of normal colorectal epithelium also express the protein, but the non-epithelial cells do not [172].

There are lower five-year survival rates for patients with CRCs that exhibit allelic loss of chromosome 18q as compared to patients whose tumors do not (for stage II, 54% versus 93%, and for stage III, 32% versus 52%) [173]. The expression of DCC, as determined by IHC, in stage II and III CRCs was a strong positive predictor for patient survival; the five-year survival rate for patients with CRCs that expressed the DCC protein was 94%, compared to 62% for CRCs that did not [172]. In CRCs, UNC5C and DCC methylation is associated with loss of gene expression [174,175].

5.8. Transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ)

The TGFβ family of cytokines consists of more than two dozen secreted peptides that are essential for normal development and which have various functions, including the regulation of cellular proliferation, differentiation, cell-cell recognition, and apoptosis. The TGFβ cytokines signal by simultaneously contacting two transmembrane serine/threonine kinases, the type I and type II receptors. Another group of proteins, the MAD-related family, function in the signaling pathways of TGFβ receptors [174–177].

The TGFβ cytokines typically exert an antiproliferative effect, and there is frequently loss of the antiproliferative response to TGFβ in the progression of neoplasia. In CRCs that are replication-error positive, this lack of response is a result of mutations in genes of the type II TGFβ receptor [178]. Other CRCs have receptors and cells resistant to TGFβ-induced growth inhibition, contributing to malignant progression [179]. In sporadic CRCs, there is a mutation in one of the MAD-related genes, MADR2. This mutation renders the gene non-functional, indicating a role for MADR2 as a tumor suppressor gene [180].

In contrast, TGFβ-1, as detected by IHC, is expressed in most CRCs, and intense staining for TGFβ-1 correlates with advanced Dukes’ stage and metastases of primary tumors [181,182]. Messenger RNA for TGFβ-1 expression in CRC cells and elevated plasma levels of messenger RNA for TGFβ-1 are associated positively with increased Dukes’ stage [183]. These findings suggest a correlation between over-expression of the TGFβ-1 gene and progression of CRN.

Other functions for TGFβ in colon tumorigenesis include stimulation of angiogenesis by inducing thymidine phosphorylase [184]; regulation of extracellular matrix adhesion molecules, including carcinoembryonic antigen [185]; and enhancement of the secretion of gelatinase B, a matrix-degrading enzyme [186]. A meta-analysis revealed that the TGFB1 509 C allele is a risk factor for development of CRCs in Asians but not Europeans [187]. A prospective study demonstrated the influence of polymorphisms in the TGFB1 pathway on CRC progression [188].

5.9. β-catenin

The β-catenin signaling is involved in colorectal carcinogenesis, but the contribution of β-catenin nuclear translocation to tumor progression is not known [189]. Nuclear translocation of β-catenin, however, may be involved in the development of intramucosal and invasive colonic cancers but not adenomas [190]. Of the 38 primary CRCs, 11 (29%) showed nuclear accumulation of β-catenin with cytoplasmic staining. Nuclear accumulation positivity was more frequently associated with lymph node metastasis than negative nuclear accumulation [100% (11/11) vs. 67% (18/27), p = 0.04]. There was a significant difference in median survival time between the nuclear β-catenin-positive group (1130 days) and the negative group (2102 days: p = 0.037). All of the patients (9/9) in the former group died when the recurrence was in the liver, but 42% (8/19) in the latter group survived, even if the recurrence was in the liver (p = 0.03) [191]. Another study involved IHC evaluation of β-catenin and p53 expression in 141 cases of primary sporadic CRCs and 45 matched metastases [192]. The combination of low β-catenin and high p53 expression in primary CRCs may be a prognostic factor in predicting the progression of the disease, the occurrence of metastasis, and a more severe outcome [192].

5.10. SMAD-4

The Smad-4 (mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4) gene is located at the chromosome 18q21.1 locus, and its product belongs to the Smad family of proteins. Smad-4 is an intracellular transducer that mediates the TGF-β-Smad-dependent signaling pathway. It also functions in translocating TGF-β complex signals into the nucleus, leading to inhibition of growth of colon epithelial cells by regulating cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [193–195]. For Smad-4 [149,194], LOH on chromosome 18q21, found at several stages of CRCs, is associated with poor prognosis in lymph node-negative (stage II) CRC patients [149, 173,196,197]. However, the prognostic value of LOH of Smad4, especially in lymph node-positive (stage III) patients remains controversial [173,196,198–200]. There is a higher incidence of Smad4 mutations in CRCs [201,202], especially in those with distant metastasis (35%) relative to local tumors (~10%) [201,202]. Other studies, however, have found Smad4 mutations only in a small proportion of CRCs [203,204]. In addition, animal studies show that Smad4 inactivation is involved in the malignant transformation of gastrointestinal adenomas [205,206], and there is a reduction in Smad4 mRNA levels during tumor progression [207]. Low immunophenotypic expression of Smad4 correlates with poor patient survival in CRCs [203,208–212]. In mice, TGF-β/Smad signaling suppresses progression and metastasis of CRC cells and tumors, and loss of Smad4 may be the underlying mechanism for the functional shift of TGF-β from a tumor suppressor to a tumor promoter. This knowledge may aid in the development of CRC therapeutics involving inhibitors of TGF-β signaling [213].

5.11. Molecular staging involving a combination of molecular markers

It is unlikely that only one or two molecular markers will be adequate for developing an effective approach to molecular staging of CRCs; a combination of multiple molecular markers is likely to be necessary. Due to limited data on p27kip–1, a candidate prognostic marker, this combination for Caucasians would, at present, be limited to p53, MUC-1, and Bcl-2. Because of variation with race and location, the combination of p53nac and Bcl-2 was of use for prognosis, but only for Caucasians overall with CRCs in the proximal and distal subgroups [81].

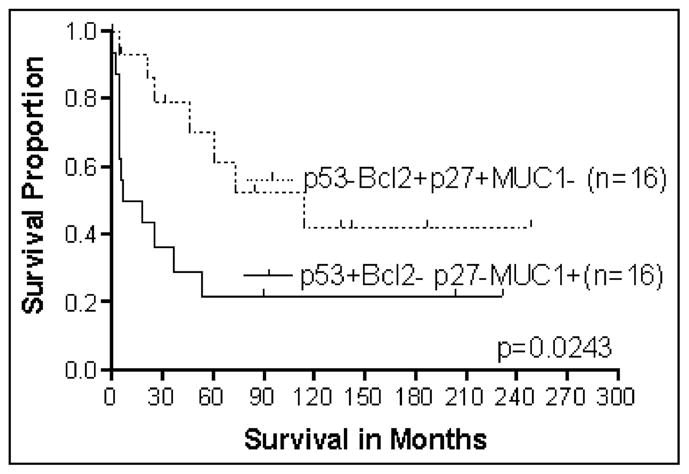

Like Bcl-2, MUC-1 interacts prognostically with p53nac so that, for Caucasians, the combination of p53nac plus MUC-1 is valuable for prognosis [126]. Because both MUC-1 and p53 are useful prognostically for Caucasian patients with CRCs, we evaluated the association of the combination of different markers with prognosis. The survival analysis for the combination of three markers (p53nac, Bcl-2 and MUC-1) demonstrated that p53nac-negative, MUC-1 negative, Bcl-2 positive was the best phenotype combination; the worst combination was p53nac-positive, MUC-1-positive, Bcl-2- negative [81]. Similarly, our unpublished findings on evaluation of a combination of 4 markers (p53nac, Bcl-2, p27kip–1, and MUC-1) demonstrated that p53nac-negative, MUC-1 negative, Bcl-2 positive, and p27kip–1 positive was the best phenotypic combination, as compared to p53nac positive, MUC-1 positive, Bcl-2 negative, p27kip–1 negative phenotypes (Fig. 6). Based on these findings, the aggressive subtype of CRCs can be identified by the molecular phenotypes. These phenotypes are given in Table 6.

Fig. 6.

Survival analysis of Caucasian patients with CRCs based on multiple markers (p53nac, Bcl-2, p27 and MUC1) expression (N = 32).

Table 6.

Molecular phenotypes of aggressive subtypes of CRCs

| CRCs in caucasians

|

CRCs in African-Americans

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal | Distal | Proximal | Distal |

| p53nac, + MUC-1 | + MUC-1, –Bcl-2 | – Bcl-2 (Weak) | – Bcl-2 |

| – Bcl-2–, – p27kip–1 | – p27kip–1 | ||

5.12. Markers independent of stage

The most valuable prognostic molecular markers are those that provide information relating to the clinical aggressiveness of tumors beyond that indicated by the tumor stage or components of the stage. Such molecular markers are probably related more to the biology of the tumor than to how advanced the lesion is at surgery. An example of a molecular pathway affecting the aggressiveness of tumors is that tumors derived from the mutator phenotype pathway and which exhibit MSI are less aggressive than other CRCs, even though they tend to be of greater size when they are surgically removed.

Prognostic molecular markers, independent of stage, can not only provide substantial information prior to surgical removal and staging of the tumor, they may add additional information: a molecular component that can be added to pathologic/clinical stage in the calculation of hazard ratios. In addition, such molecular markers can aid in the decision concerning whether or not to use adjuvant and/or novel therapies for early lesions, especially Stage II lesions.

To date, the molecular markers p53, p27kip–1, Bcl-2 and MUC-1 show promise as being useful prognostically for CRCs, but each awaits more complete validation. In our view, no one molecular marker will be adequate for evaluating all CRCs. Rather, groups of molecular markers will be useful for specific subsets of CRCs, as subdivided by race and/or anatomic location of the primary tumor.

Variation of the usefulness of prognostic biomarkers with stage is most likely related to how factors controlling mitoses are regulated. Since multiple genes control metastases, unless a prognostic biomarker also is related to a gene regulating metastasis, the biomarker is unlikely to be independent of stage. Instead, the prognostic gene will first influence the rate at which the lesion increases in size up to and until metastasis. Because this influence on prognosis will continue, to some degree, after metastasis, the biomarker may be less indicative of tumor progression, which will then be controlled primarily by a gene modulating metastasis.

It is likely that genes controlling metastases to local lymph nodes are different from those controlling metastases from lymph nodes to the liver. This may explain differences in prognostic genes related to nodal metastasis, but not distant metastasis.

6. Novel prognostic markers

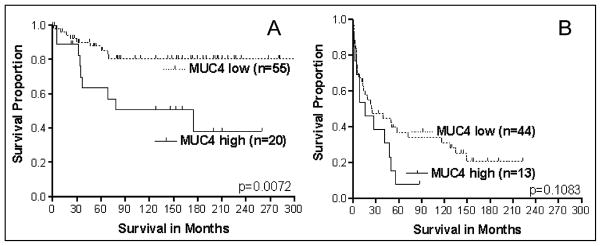

6.1. MUC4

MUC4 is aberrantly expressed in CRCs, but its prognostic value is unknown. We evaluated 132 CRCs for the IHC expression of MUC4 and found that patients with early-stage tumors (I and II) with high MUC4 expression had a shorter disease-specific survival than those with low expression (log-rank, p = 0.007). Tumors from patients with advanced-stage CRCs (III and IV) did not demonstrate such a difference (log-rank, p = 0.108) (Fig. 7) [214]. The multivariate regression models generated separately for early- and advanced-stage patients confirmed that increased expression of MUC4 is an independent indicator of a poor prognosis only for patients with early-stage CRCs (hazard ratio, 3.77; confidence interval, 1.46–9.73). Hence, increased MUC4 expression is a predictor of poor survival of patients with early stage CRCs [214].

Fig. 7.

Survival analysis of CRC patients (N = 132) based on MUC4 expression. A = stage I and II (N = 75); B = Stage III and IV (N = 57).

6.2. Rabphilin-3A-like (RPH3AL)

The RPH3AL protein has structural similarities with rabphillin-3A, RIM, and synaptotagmin-like proteins (Slp1 to 5), which contain modules (C2 domains) for protein and phospholipid interaction. Since RPH3AL lacks these domains, it was originally named Noc2 (no C2 domains). The RPH3AL gene was originally discovered as a pancreatic islet gene encoding the RAS-associated protein (Rab)-binding domain of rabphilin [215]. Although the precise functions of RPH3AL are not known, the gene is involved in the regulation of endocrine endocytosis through its interactions with the cytoskeleton [215,216]. Our recent study showed that Noc2, Rab3A, Rab27A, and RIM2, together with the islet cell hormones, insulin and glucagon, are present in normal and endocrine tumor tissues of human pancreas [217]. For CRCs, ours [218,219] and one other study [220] of this tumor type have involved mutational analysis of the RPH3AL gene; they have demonstrated six missense mutations resulting in amino acid substitutions in the coding region of this gene. This suggested a tumor suppressor role for RPH3AL, but only in a few cases (our study, 5 of 95, 5%; and other study, 6 out of 50, 12%) [218,220]. We, however, have detected LOH at this gene locus in a considerable proportion of CRCs (58%). The incidence of LOH was associated with depth of invasion of the tumor, nodal metastasis, distant metastasis, high-grade tumor differentiation, and short survival of patients [218,219]. Furthermore, our studies with CRCs have identified five missense mutations in RPH3AL and several SNPs and have demonstrated the clinical relevance of an SNP at 5′UTR-25 [221].

6.3. miRNAs

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a family of small (20 to 24-nucleotide), non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level [222]. Since approximately half of the known human miRNAs are located at cancer-associated regions of the genome, miRNAs may function in the pathogenesis of various human cancers [223]. Many proteins involved in key signaling pathways of CRCs, such as members of the Wnt/β-catenin and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI-3-K) pathways, KRAS, p53, extracellular matrix regulators, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) transcription factors, are altered and are apparently regulated in CRCs by miRNAs [224]. In cultured cells, miR-135a and miR-135b decrease translation of the APC transcript. Of note, these molecules are up-regulated in colorectal adenomas and carcinomas, and they correlate with low APC levels [225]. The KRAS oncogene is a direct target of the let-7 miRNA family [226] and miR-143 [227]. Inhibition of KRAS expression by miR-143 blocked constitutive phosphorylation of MAPK [227]. Studies based on microRNA arrays found a consistent loss of miR-126 expression in colon cancer lines as compared to normal human colon epithelia; reconstitution of miR-126 resulted in a growth reduction [228]. miR-21 is the miRNA most frequently up-regulated in CRCs. It is hypothesized that suppression of PTEN controlled by miR-21 is associated with augmentation of PI-3-K signaling and progression of CRCs [229–231].

Several groups have described aspects of the connection between p53 and the miRNA network [232]. Members of the conserved miR-34a-c family are direct transcriptional targets of p53. Genes responsive to miR-34a are those that regulate cell-cycle progression, cellular proliferation, apoptosis, DNA repair, and angiogenesis [233]. The high frequency of their methylation in 1p36, the genomic interval harboring miR-34a, in CRCs and its contribution to the p53 network imply that miR-34a, b, and c function as tumor suppressors that can be lost during development of CRCs [222]. Up-regulation of miR-21 in CRC cells increases their migratory and invasive capacities in a manner similar to that of glioblastomas [234]. Furthermore, miR-21 acts on PDCD4, a tumor suppressor gene that is an independent prognostic factor in resected CRCs and negatively regulates intravasation through the invasion-related urokinase receptor gene (uPAR) [235].

As determined with a mouse model of colon cancer, the angiogenic activity of c-Myc is due, at least in part, to downstream activation of the miR-17-92 cluster d [236]. Over-expressed cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) contributes to the growth and invasiveness of tumor cells in patients with CRCs. For CRC cell lines, there is an inverse correlation between COX-2 and miR-101 expression, and the direct translational inhibition of COX-2 mRNA is mediated by miR-101 [237].

Various approaches have been used to predict and identify functional SNPs within miRNA binding sites and to evaluate their biological relevance [238]. Regarding CRCs, of eight candidate genes predicted by computer simulation, the genes for CD86, a co-stimulatory ligand on lymphocytes, and for the insulin receptor carry SNPs that are associated with the risk of sporadic CRCs (odds ratios 2.74 and 1.94, respectively) [239]. The biological relevance of these SNPs, however, has not been confirmed by functional studies in cultured cells.

CRC patients have a serum miRNA profile different from that of healthy subjects [240]. In all cases, 69 miRNAs were detected in the sera from CRC patients but not in sera from healthy subjects. CRC patients share several serum miRNAs (miR-134, miR-146a, miR-221, miR-222, and miR-23a) with lung cancer patients.

CRC patients with tumors expressing high levels of miR-200c have a poorer prognosis, regardless of tumor stage; and p53 mutations, commonly found in CRCs, are associated with greater than two-fold miR-200c overexpression [241]. miR-21 overexpression correlates with the established prognostic factors (nodal stage, metastatic disease, and UICC stage) [231]. In tumors of CRC patients, 37 miRNAs are differentially expressed [230]. From this group, miR-20a, miR-21, miR-106a, miR-181b, and miR-203 were found, by Cox regression analysis, to be associated with poor survival and were selected for validation. Validation was performed by measuring expression of miRNAs by use of real-time PCR in tumor and paired non-tumor tissues [230]. In the validation set, only high expression of miR-21 was associated with a poor prognosis; this association was independent of age, sex, and tumor location. Multivariate analysis further revealed that high miR-21 expression in tumors was associated with poor survival, independent of the tumor stage. Similar findings were also found in our preliminary studies [242]. In patients who received adjuvant therapy, high miR-21 expression indicated a poor response to therapy [230]. Patients having Stage II CRC tumors with high expression of miR-320 or miR-498 had shorter progression-free survival than those whose tumors showed low expression [243].

7. Predictive markers

Adjuvant therapy with 5-fluorouracil (5FU)/leucovorin (LV) or 5FU/LV/irinotecan moderately reduces recurrence rates and the risk of dying from resectable CRCs (Stage III) [244–246]. The combination of 5FU/LV/oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) prolongs the survival in second-line treatment of patients with disseminated disease [247]. Data from MOSAIC [248,249] and QUASAR [250] trials on use of FOLFOX demonstrate a relapse/progression-free survival benefit for patients with Stage II or III CRCs. Current treatment recommendations in the US, however, include using FOL-FOX not only for Stage III disease but also for Stage II disease, if high-risk clinical features are presented. Improved surgical techniques [251–254], pre- or post-surgical radiotherapy [253,255], and post-surgical radiotherapy and chemotherapy have decreased failure rates for rectal cancers [256–259]. Innovative treatment modalities, such as anti-angiogenic and antimetastatic agents [260–262], farnesyl transferase inhibitors [263], novel vaccines [264,265], and gene therapy approaches are in clinical trials [266,267]. Findings of several retrospective studies and prospective clinical trials have been inconclusive, because patients received different 5FU regimens, and each regimen involved a different mechanism of action. Indeed, there is a reported survival benefit of 5FU-based treatment in patients with Stage III [268] or Stage IV [269] disease of the distal colon; however, such a benefit was not observed in another study [270]. The role of adjuvant treatment in patients with Stage II CRCs remains controversial [271].

The anti-tumor activity of 5FU has been related to its induction of apoptosis by damaging DNA and to its alteration of the expression profiles of pro- and anti-apoptotic molecules (Bax, Bcl-2, and p53). Chemo-resistance may depend on the function and relations between pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins [272–274]. However, our experience in assessing the prognostic value of p53nac [275,276], and expression of Bcl-2 [115,277,278], Bax [279,280], p27kip–1 [81,131], MUC1 [126], suppressin [281], MSI [282,283], and the Rabphillin-3A-like gene [284–286] in CRCs has suggested that these molecular markers have different biologic consequences based on tumor location, pathologic stage, and race/ethnicity of patients who experience only surgery.

7.1. p53

Mutant forms of the p53 protein can be detected by routine IHC; but native p53 protein can not. The association of p53 abnormalities in CRCs with survival has been studied extensively, but studies in relation to abnormal expression of p53 and the therapy responses are few. Two retrospective studies, however, demonstrated that patients whose Stage III tumors did not exhibit p53 abnormalities benefited from 5FU-based treatments [287,288].

7.2. Bcl-2

In CRCs, the lack of Bcl-2 expression correlates with tumor invasion, metastasis, and recurrence [112, 113]. Studies by Sinicrope et al. [289,290] and by us [277,278] indicate that patients with CRCs expressing Bcl-2 have a better clinical outcome than patients with tumors that do not (also reviewed in [115,277,278, 291]). There was, however, no significant association between Bcl-2 expression and the clinical outcome for patients with metastatic CRCs who received 5FU/LV treatment [292].

7.3. Bax

Bax/Bcl-2 heterodimers protect cells from apoptosis [293]. In contrast, an abundant amount of Bax causes formation of Bax homodimers that make the cells susceptible to apoptosis [106,294]. Furthermore, patients with hepatic metastases from CRCs having increased expression of Bax had higher survival rates [274]. Experiments involving cells in culture demonstrate that the lack of Bax expression abolishes the apoptotic response to chemopreventive and anti-inflammatory drugs [295].

7.4. p21waf–1

p21waf–1, a gene activated by p53, is a target of p53 that binds to and inhibits the function of the cyclin-cdks complexes and thus halts cell cycle progression [296, 297]. The p21 gene is induced by DNA-damaging agents that trigger G1 arrest of cells, both in a p53-dependent and -independent manner [298,299]. Studies involving use of IHC or hybridization in situ have demonstrated that increased expression of p21waf–1 in CRCs is associated with better survival [300–302]; however, its predictive value is unknown.

7.5. p27kip–1

This protein also appears to have functions in the cell cycle and in cell differentiation [303]. Overexpression of p27kip–1 augments apoptosis induced in cultured cells by 5FU [304]. Decreased expression of the p27kip–1 protein is associated with large-sized CRCs and with lymph node metastases. Low expression is an indicator of a poor clinical outcome [127,128,305–307], but only for Stage III tumors [131].

7.6. Ki67

IHC detection of cell cycle-associated Ki67 has been utilized to assess proliferation in human malignancies. Studies designed to examine the potential association of proliferation with tumor progression, biologic behavior, or patient prognosis generally have been inconclusive, and in some instances, contradictory [300,308]. There are, however, few studies that have focused on the predictive value of Ki-67 in CRCs.

7.7. Thymidylate synthase (TS)

TS is a target for 5FU inhibition of cell proliferation. Its levels predict response to therapies such as 5FU/LV, methotrexate-5FU, and raltitrexed [309–311]. The expression of TS, measured by IHC, is an independent prognosticator of disease-free and overall survival of patients, particularly those with rectal tumors [312]. TS expression is higher in left-sided CRCs and is associated with poor patient survival [313]. Nuclear expression of TS in normal colonic mucosa appears to be a predictive factor that can be used to identify a sub-set of patients at risk of developing severe gastrointestinal toxicities related to 5FU-based therapies [314].

7.8. Thymidine phosphorylase (TP)

TP is an enzyme involved in the metabolism of 5FU, catalyzing the reversible phosphorolysis of thymidine to thymine and 2-deoxyribose-1-phosphate. In CRCs, decreased expression of TP, like TS, is associated with a better response to 5FU therapy [310,315].

7.9. Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD)

DPD, the rate-limiting enzyme in 5FU metabolism, converts 5FU to dihydrofluorouracil [316]. Cancer patients deficient in DPD may experience profound systemic toxicity in response to 5FU [317]. Furthermore, for CRCs, high levels of DPD expression, measured as either mRNA or protein, correlate with resistance to 5FU [315,318,319].

7.10. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)

This protein, a member of the tyrosine kinase family, is often over-expressed in epithelial tumors, including CRCs. Therapeutic agents targeted to EGFR include the monoclonal antibody (MAb) C225 and Iressa (ZD1839). These agents have only modest antitumor activity when administered as single agents but display considerable synergism with cytotoxic drugs [320–323].

7.11. VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is involved in tumor angiogenesis. The expression of VEGF in Stage II colonic cancers predicts for recurrence after surgery [324]. Results of a randomized phase II trial of metastatic CRCs suggest that administration of an MAb against VEGF in combination with chemotherapy results in improved response rates and a longer time to progression compared to chemotherapy alone [325].

7.12. MUC1

In CRCs, higher expression of MUC1 correlates with an increased incidence of regional lymph node metastasis and liver metastasis [125,126,326]. Its abundance and interaction with class I MHC molecules make it a potential target for immunotherapy. A phase I study of metastatic or locally advanced colonic carcinoma reveals that immunization by a MUC1-mannan fusion protein elicits an increased humoral response in patients with advanced-stage CRCs and suggests that MUC1 vaccine therapy may be useful for patients with advanced disease [327].

7.13. KRAS

A KRAS mutation is present in 30–49% of CRCs. Activating mutations of the KRAS gene are biomarkers for resistance to cetuximab or panitumumab. Anti-EGFR therapies have been approved for the treatment of metastatic CRCs, but only on condition that the mutation state of the KRAS gene is first determined. This is because the combination of chemotherapy with anti-EGFR is expected to increase the response rate only for patients with the wild-type KRAS gene [328]. In addition, among CRCs carrying wild-type KRAS, mutation of BRAF or PIK3CA or loss of PTEN expression may be associated with resistance to EGFR-targeted MAb treatment. These additional biomarkers require further validation before being incorporated into clinical practice. The use of KRAS mutations as selection biomarkers for treatment with the anti-EGFR MAb (e.g., panitumumab or cetuximab) is a major step toward individualized treatment for patients with metastatic CRCs [224].

7.14. BRAF mutations

Mutations in the BRAF gene may be useful for predicting the efficacy/response to EGFR inhibitors, such as cetuximab and panitumumab, as is expression of KRAS gene mutations [329]. In general, mutations in either KRAS or BRAF exclude mutations in other genes. Further, patients bearing metastatic CRCs with mutations in the BRAF gene and who had wild-type KRAS did not respond to treatment with these EGFR inhibitors and were more likely to experience disease progression [330].

7.15. Microsatellite instability (MSI)

Adjuvant therapy with 5FU benefited patients with CRCs exhibiting chromosomal instability but not those with tumors exhibiting MSI [270]. In this clinical trial, 5FU-based adjuvant therapy actually decreased the survival of patients with CRCs exhibiting MSI. These findings are counterintuitive to the findings that MSI-H in sporadic CRCs is associated with a less aggressive phenotype and with improved survival when compared with stage-matched microsatellite-stable and MSI-Low CRCs [331,332]. Nevertheless, the predictive value of MSI-H remains controversial [333,334]. Genome-wide surveys show associations of the locus at 8q24.21 for CRC patients under 50 years age [335] and the locus at 11q23.1 for female Lynch syndrome patients [336]. Larger studies are required to establish the value of MSI as a predictive marker.

7.16. miRNAs

Let-7g and miR-181b are indicators for response to chemotherapy based on the fluoropyrimidine S-1 [337].

8. Candidate molecular markers of CRC progression

Some molecular markers have potential usefulness for assessing the clinical outcomes in many cancers, including CRCs; however, the following markers need further validation in larger cohorts of CRC samples to establish their value in assessing clinical outcomes.

8.1. CDKN1A

CDKN1A (p21, Cip1), a protein encoded by the CD-KN1A gene located on chromosome 6 (6p21.2) [338], binds to and inhibits the activity of cyclin-CDK2 or -CDK4 complexes, and thus functions as a regulator of cell cycle progression at the G1 phase [338]. Expression of this gene is tightly controlled by p53, through which this protein mediates the p53-dependent G1 phase arrest in response to stress stimuli [339]. In CRCs, decreased expression of the CDKN1A protein is associated with a poor clinical outcome [340]. No studies, however, have evaluated the expression of CD-KN1A in CRCs with an emphasis on its predictive capacity.

8.2. CDK4

This catalytic subunit of the protein kinase complex is associated with progression of the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Its activity is restricted to the G1-S phase, which is controlled by the regulatory subunits, D-type cyclins and the CDK inhibitor p16 (INK4a). CDK4 is responsible for phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma gene product (Rb). For a variety of cancers, mutations in this gene and in genes for its related proteins, D-type cyclins, p16 (INK4a), and Rb, are associated with tumorigenesis [341]. In familial melanoma, there are germline mutations in the p16INK4a binding domain of CDK4 [342].

8.3. GADD45

In humans and rodents, the GADD (growth arrest and DNA damage) genes are induced in response to DNA damage [343]. GADD45, the only member of the family that is induced by ionizing radiation or by genotoxic stress in the presence of wild-type 53 [344, 345], encodes a nuclear acidic protein of 165 amino acids [346], which is widely expressed in normal tissues and particularly in quiescent cells [347]. The GADD45 protein interacts directly with the essential replication factor, proliferating cell nuclear antigen, to block DNA replication and to repair damaged DNA [348]. As determined by studies with cultured cells, GADD45 regulates cell growth by arresting cells in the G2-phase of the cell cycle [349]. No mutations in the GADD45 gene are noted in various human malignancies or cancer cell lines [350,351]; however, a small proportion of pancreatic cancers exhibit mutations in this gene [352].

8.4. TP53I3

The gene PIG3 (p53-induced gene 3) is induced by p53 but not by p53 mutants unable to induce apoptosis, suggesting that the PIG3 protein is involved in p53-mediated cell death [353,354]. It contains a p53 consensus binding site in its promoter region and a downstream pentanucleotide microsatellite sequence. By interacting with the downstream pentanucleotide microsatellite sequence, p53 transcriptionally activates this gene. The microsatellite is polymorphic, with a varying number of pentanucleotide repeats directly correlating with the extent of transcriptional activation by p53. This polymorphism may be associated with differential susceptibility to cancer [338].

8.5. BMP4

BMP4 belongs to the TGF-β superfamily of proteins. It is involved in bone and cartilage development, especially tooth and limb development and fracture repair, and in muscle development, bone mineralization, and uteric bud development [355]. BMP-4 enhances growth factor-induced proliferation of mammary epithelial cells [356]. In ovarian cancer cells, autocrine BMP4 signaling regulates expression of the ID3 proto-oncogene [357].

8.6. FLRT3