Abstract

The overhead throwing athlete is an extremely challenging patient in sports medicine. The repetitive microtraumatic stresses imposed on the athlete’s shoulder joint complex during the throwing motion constantly place the athlete at risk for injury. Treatment of the overhead athlete requires the understanding of several principles based on the unique physical characteristics of the overhead athlete and the demands endured during the act of throwing. These principles are described and incorporated in a multiphase progressive rehabilitation program designed to prevent injuries and rehabilitate the injured athlete, both nonoperatively and postoperatively.

Keywords: glenohumeral joint, scapula, rotator cuff, internal impingement, superior labral anterior posterior lesion, baseball

The overhead throwing athlete is an extremely challenging patient in sports medicine, with unique physical characteristics as the result of sport competition. The repetitive microtraumatic stresses placed on the athlete’s shoulder joint complex during the throwing motion challenges the physiologic limits of the surrounding tissues.

Consequently, it is imperative to emphasize the preventative care and treatment of these athletes. Injury may occur because of muscle fatigue, muscle weakness and imbalances, alterations in throwing mechanics, and/or altered static stability. A comprehensive program designed for the overhead athlete is necessary to avoid injury and maximize performance. Unfortunately, not all injuries may be prevented, because the act of throwing oftentimes exceeds the ultimate tensile strength of the stabilizing structures of the shoulder.17,18

Part 1 of this series, on the examination and treatment of the overhead athlete, described the unique physical characteristics and examination process for the injured athlete.49 Part 2 descibes a proper treatment program and emphasizes the unique physical characteristics and stresses observed during the act of throwing.

Principles of Injury Prevention and Treatment Programs

Several general principles should be incorporated into the development of injury prevention and treatment programs for the thrower’s shoulder. Injury prevention and treatment programs share considerable overlap given that both are based on similar principles.

Maintain Range of Motion

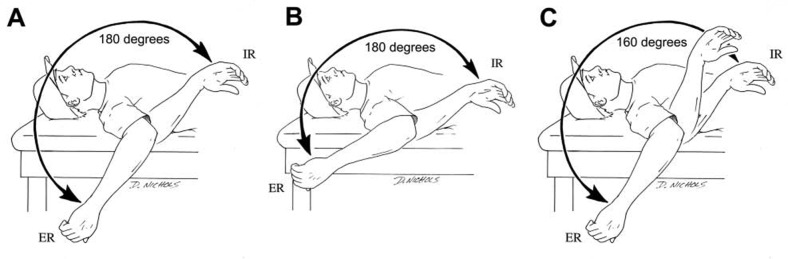

The first principle involves maintaining appropriate “thrower’s motion” at the glenohumeral joint. The shoulder in overhead athletes exhibits excessive motion, ranging from 129° to 137° of external rotation (ER), 54° to 61° of internal rotation (IR), and 183° to 198° of total ER-IR motion.49 Although the dominant shoulder has greater ER and less IR, the combined total motion should be equal bilaterally.49,54,69 More important, the act of throwing reduces IR and total motion (Figure 1).54 Studies by Ruotolo et al57 and Myers et al43 have both shown that a loss of total motion correlates with a greater risk of injury.

Figure 1.

The total motion concept. The combination of external rotation (ER) and internal rotation (IR) equals total motion and is equal bilaterally in overhead athletes, although shifted posteriorly in the dominant (A) versus nondominant (B) shoulder. Pathological loss of internal rotation will result in a loss of total motion (C).

Thus, it is important to maintain motion over the course of a season. Reinold et al54 theorized that the loss of IR and total motion after throwing is the result of eccentric muscle damage as the external rotators and other posterior musculature attempt to decelerate the arm during the throwing motion. In general, total motion should be maintained equal to that of the nondominant shoulder by frequently performing gentle stretching. Caution should be emphasized against overaggressive stretching in an attempt to gain mobility, in favor of stretching techniques to maintain mobility.

It is equally important to regain full range of motion following injury and surgery. Time frames vary for each injury. Athletes who are attempting to return to throwing before regaining full motion have a difficult time returning to competition without symptoms. The clinician should ensure that full motion has been achieved before allowing the initiation of an interval throwing program.

Maintain Strength of the Glenohumeral and Scapulothoracic Musculature

Because the act of throwing is so challenging for the static and dynamic stabilizing structures of the shoulder, strengthening of the entire upper extremity—including shoulder, scapula, elbow, and wrist—is essential for the overhead thrower. A proper program is designed per the individual needs of each athlete, the unique stress of the throwing motion, and the available research on strengthening each muscle.48 Emphasizing the external rotators, scapular retractors, and lower trapezius is important according to electromyographic studies of the throwing motion.48,50,52 These exercises serve as a foundation for the strengthening program, to which skilled and advanced techniques may be superimposed.

Emphasize Dynamic Stabilization and Neuromuscular Control

The excessive mobility and compromised static stability observed within the glenohumeral joint often result in injuries to the capsulolabral and musculotendinous structures of the throwing shoulder. Efficient dynamic stabilization and neuromuscular control of the glenohumeral joint is necessary for overhead athletes to avoid injuries.12 This involves neuromuscular control: efferent (motor) output in response to afferent (sensory) stimulation. It is one of the most overlooked yet crucial components of injury prevention and treatment programs for the overhead athlete.

Neuromuscular control of the shoulder involves not only the glenohumeral but also the scapulothoracic joint. The scapula provides a base of support for muscular attachment and dynamically positions the glenohumeral joint during upper extremity movement. Scapular strength and stability are essential to proper function of the glenohumeral joint.

Neuromuscular control techniques should be included in rehabilitation programs for the overhead athlete—specifically, rhythmic stabilization, reactive neuromuscular control drills, closed kinetic chain, and plyometric exercises.12,16,48,51,69,73 Closed kinetic chain exercises stress the joint in a load-bearing position, resulting in joint approximation.12 The goal is to stimulate receptors and facilitate co-contraction of the shoulder force couples.46

Plyometric exercises provide quick, powerful movements by a prestretch of the muscle, thereby activating the stretch shortening cycle.20,62,73 Plyometric exercises increase the speed of the myotactic/stretch reflex, desensitize the Golgi tendon organ, and increase neuromuscular coordination.73

Core and Lower Body Training

The lower extremities are vital in the development of force during the throwing motion. Core stabilization drills and lower body training further enhance the transfer of kinetic energy and proximal stability with distal mobility of the upper extremity. Any deficits in strength, endurance, or neuromuscular control of the lower body will have a significant impact on the forces of the upper extremity and the athlete’s ability to produce normal pitching mechanics.

Core stabilization is based on the kinetic chain concept: Imbalance at any point of the kinetic chain results in pathology. Movement patterns such as throwing require a precise interaction of the entire kinetic chain to become efficient. An imbalance of strength, flexibility, endurance, or stability anywhere within the chain may result in fatigue, abnormal arthrokinematics, and subsequent compensation.

Off-Season Preparation

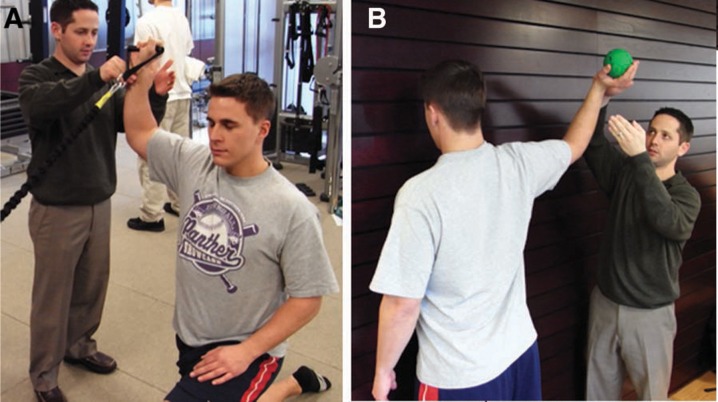

The off-season is a valuable time for the athlete to rest, regenerate, and prepare for the rigors of an upcoming season. The main components of a player’s off-season include an initial period of rest, followed by a progressive full-body strength and conditioning program. The goal of the off-season is to build enough strength, power, and endurance to compete without the negative effects of fatigue or weakness from overtraining or undertraining. Whereas the timing of the in- and off-season components of an athlete’s yearly cycle may vary greatly among athletes at different skill levels, the concepts and goals for the off-season remain the same. Training is based on Matveyev’s periodization concept with individualized attention to each athlete’s specific goals (Figure 2).35

Figure 2.

The concept of periodization as defined by Matveyev35 (A) and customized per the schedule of a professional baseball player (B).

At the conclusion of a competitive season, athletes should remain physically active while taking time away from their sports. Recreational activities are encouraged, such as swimming, golfing, cycling, and jogging. This is also a valuable time to rehabilitate any lingering injury that may have been managed through the season.

The remainder of the off-season is used to build a baseline of strength, power, endurance, and neuromuscular control—the goal of which is to maximize physical performance before the start of sport-specific activities. Doing so will ensure that the athlete has adequate physical fitness to withstand the demands of the competitive season.

In-Season Maintenance

Equally as important as preparing for the competitive season is maintaining gains in strength and conditioning during the season. The chronic, repetitive nature of a long season often results in a decline in physical performance.

Whereas a full-body strength and conditioning program is imperative, attention should be paid to the throwing shoulder and the muscles of the glenohumeral and scapulothoracic joints. Any fatigue or weakness in these areas can lead to injury through a loss of dynamic stability.

An in-season maintenance program should focus on strength and dynamic stability while adjusting for the workload of a competitive season.

Rehabilitation Progression

In addition to eliminating pain and inflammation, the rehabilitation process for throwing athletes must restore motion, muscular strength, and endurance, as well as proprioception, dynamic stability, and neuromuscular control (Table 1). As the athlete advances, sport-specific drills are added to prepare for a return to competition. Neuromuscular control drills are performed throughout, advancing as the athlete progresses, to provide a continuous challenge to the neuromuscular control system.

Table 1.

Treatment guidelines for the overhead athlete.a

| Phase 1: Acute Phase | |

| Goals |

|

| Treatment | Abstain from throwing until pain-free full ROM and full strength—specific time determined by physician |

| Modalities |

|

| Flexibility |

|

| Exercises |

|

| Criteria to progress to phase 2 |

|

| Phase 2: Intermediate Phase | |

| Goals |

|

| Flexibility |

|

| Exercises |

|

| Criteria to progress to phase 3 |

|

| Phase 3: Advanced Strengthening Phase | |

| Goals |

|

| Exercises |

|

| Criteria to progress to phase 4 |

|

| Phase 4: Return-to-Activity Phase | |

| Goals |

|

| Exercises |

|

ROM, range of motion; IR, internal rotation; ER, external rotation; RS, rhythmic stabilizations; 90/90, 90° of abduction and 90° of external rotation.

Acute Phase

The acute phase of rehabilitation begins immediately following injury or surgery by abstaining from throwing activities. The duration of the acute phase depends on the chronicity of the injury and the healing constraints of the involved tissues.

Range of motion exercises are promptly performed in a restricted range, according to the theory that motion assists in the enhancement and organization of collagen tissue and the stimulation of joint mechanoreceptors and that it may assist in the neuromodulation of pain.58-60 The rehabilitation program should allow for progressive loads, beginning with gentle passive and active-assisted motion.

Flexibility exercises for the posterior shoulder musculature are also performed early. The posterior shoulder is subjected to extreme repetitive eccentric contractions during throwing, which may result in soft tissue adaptations and loss of IR motion,49,54 which may not be due to posterior capsular tightness. Conversely, it appears that most throwers exhibit significant posterior laxity when evaluated.8,9 Thus, common stretches should include horizontal adduction across the body, IR stretching at 90° of abduction, and the sleeper stretch (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

A, the sleeper stretch for glenohumeral internal rotation; B, the body should be positioned so that the shoulder is in the scapular plane.

Figure 4.

A, cross-body horizontal adduction stretch; B, the clinician may also perform the stretch with the shoulder in internal rotation.

The cross-body horizontal adduction stretch may be performed in a straight plane or integrated with IR at the glenohumeral joint (Figure 4). Overaggressive stretching with the sleeper stretch should be avoided (Figure 3). Frequent, gentle stretching yields far superior results than does the occasional aggressive stretch. Stretches or joint mobilizations for the posterior capsule should not be performed unless the capsule has been shown to be mobile on clinical examination.

The rehabilitation specialist should assess the resting position and mobility of the scapula. Throwers frequently exhibit a posture of rounded shoulders and a forward head. This posture is associated with muscle weakness of the scapular retractors and deep neck flexor muscles owing to prolonged elongation or sustained stretches.48,65 In addition, the scapula may appear protracted and anteriorly tilted. An anteriorly tilted scapula contributes to a loss of glenohumeral IR.7,32 This scapular position is associated with tightness of the pectoralis minor, upper trapezius, and levator scapula muscles and weakness of the lower trapezius, serratus anterior, and deep neck flexor muscle groups.48,65 Tightness of these muscles can lead to axillary artery occlusion and neurovascular symptoms, such as arm fatigue, pain, tenderness, and cyanosis.44,56,64 Muscle weakness may result in improper mechanics or shoulder symptoms. Stretching, soft tissue mobilization, deep tissue lengthening, muscle energy, and other manual techniques may be needed in these athletes.

Depending on the severity of the injury, strengthening often begins with submaximal, pain-free isometrics for all shoulder and scapular movements. Isometrics should be performed at multiple angles throughout the available range of motion, with emphasis on contraction at the end.

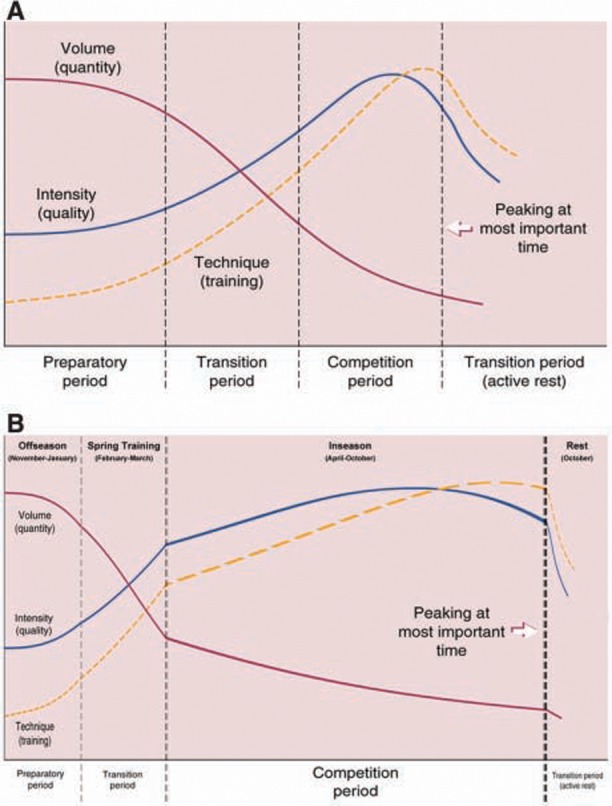

Manual rhythmic stabilization drills are performed for internal and external rotators with the arm in the scapular plane at 30° of abduction (Figure 5). Alternating isometric contractions facilitate co-contraction of the anterior and posterior rotator cuff musculature. Rhythmic stabilization drills may also be performed with the patient supine and with the arm elevated to approximately 90° to 100° and positioned at 10° of horizontal abduction (Figure 6). This position is chosen for the initiation of these drills due to the combined centralized line of action of both the rotator cuff and deltoid musculature, generating a humeral head compressive force during muscle contraction.45,68 The rehabilitation specialist employs alternating isometric contractions in the flexion, extension, horizontal abduction, and horizontal adduction planes of motion. As the patient progresses, the drills can be performed at variable degrees of elevation, such as 45° and 120°.

Figure 5.

Rhythmic stabilization drills for internal and external rotation with the arm at 90° of abduction and neutral rotation (A) and 90° of external rotation (B).

Figure 6.

Rhythmic stabilization drills for flexion and extension with the arm elevated to 100° of flexion in the scapular plane.

Active range of motion activities are permitted when adequate muscle strength and balance have been achieved. With the athlete’s eyes closed, the rehabilitation specialist passively moves the upper extremity in the planes of flexion, ER, and IR; pauses; and then returns the extremity to the starting position. The patient is then instructed to actively reposition the upper extremity to the previous location. The rehabilitation specialist may perform these joint-repositioning activities throughout the available range of motion.

Basic closed kinetic chain exercises are also performed during the acute phase. Exercises are initially performed below shoulder level. The athlete may perform weight shifts in the anterior/posterior and medial/lateral directions. Rhythmic stabilizations may also be performed during weight shifting. As the athlete progresses, a medium-sized ball may be placed on the table and weight shifts may be performed on the ball. Load-bearing exercises can be advanced from the table to the quadruped position (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Rhythmic stabilization drills for the throwing shoulder while weightbearing in the quadruped position.

Modalities such as ice, high-voltage stimulation, iontophoresis, ultrasound, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications may be employed as needed to control pain and inflammation. Iontophoresis may be particularly helpful in reducing pain and inflammation during this phase of rehabilitation.

Intermediate Phase

The intermediate phase begins once the athlete has regained near-normal passive motion and sufficient shoulder strength balance. Lower extremity, core, and trunk strength and stability are critical to efficiently perform overhead activities by transferring and dissipating forces in a coordinated fashion. Therefore, full lower extremity strengthening and core stabilization activities are performed during the intermediate phase. Emphasis is placed on regaining proprioception, kinesthesia, and dynamic stabilization throughout the athlete’s full range of motion, particularly at end range. For the injured athlete midseason, it is common to begin in the intermediate phase or at least progress to this phase within the first few days following injury. The goals of the intermediate phase are to enhance functional dynamic stability, reestablish neuromuscular control, restore muscular strength and balance, and regain full range of motion for throwing.

During this phase, the rehabilitation program progresses to aggressive isotonic strengthening activities with emphasis on restoration of muscle balance. Selective muscle activation is also used to restore muscle balance and symmetry. The shoulder external rotator muscles and scapular retractor, protractor, and depressor muscles are isolated through a fundamental exercise program for the overhead thrower.48,70-72 This exercise program is based on the collective information derived from electromyographic research of numerous investigators.¶ These patients frequently exhibit ER weakness and benefit from side lying ER and prone rowing into ER. Both exercises elicit high levels of muscular activity in the posterior cuff muscles.52

Drills performed in the acute phase may be progressed to include stabilization at end ranges of motion with the patient’s eyes closed. Rhythmic stabilization exercises are performed during the early part of the intermediate phase. Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation exercises are performed in the athlete’s available range of motion and so progress to include full arcs of motion. Rhythmic stabilizations may be incorporated in various degrees of elevation during the proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation patterns to promote dynamic stabilization.

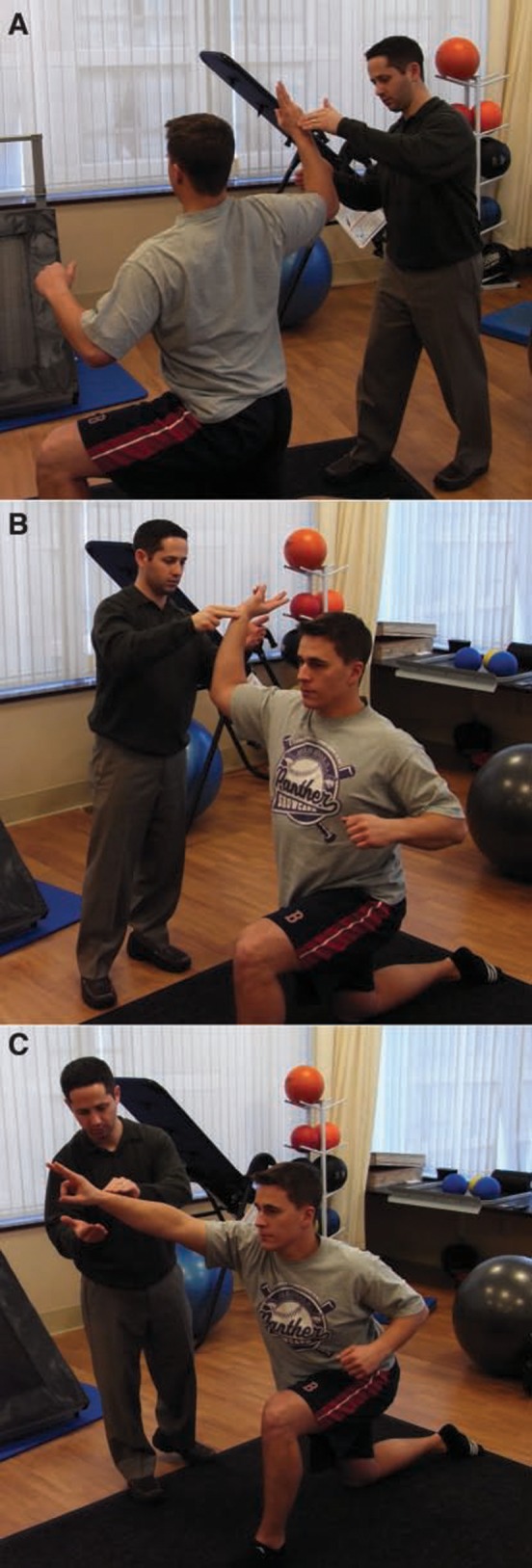

Manual-resistance ER is also performed during the intermediate phase. By applying manual resistance during specific exercises, the rehabilitation specialist can vary the amount of resistance throughout the range of motion and incorporate concentric and eccentric contractions, as well as rhythmic stabilizations at end range (Figure 8). As the athlete regains strength and neuromuscular control, ER and IR with tubing may be performed at 90° of abduction.

Figure 8.

Manual-resistance side-lying external rotation with end-range rhythmic stabilizations.

Scapular strengthening and neuromuscular control are also critical to regaining full dynamic stability of the glenohumeral joint. Isotonic exercises for the scapulothoracic joint are added, along with manual-resistance prone rowing. Neuromuscular control drills and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation patterns may also be applied to the scapula (Figures 9 and 10).

Figure 9.

Arm elevation against a wall, with the patient isometrically holding a light-resistance band into external rotation to facilitate posterior rotator cuff and scapular stabilization during scapular elevation and posterior tilting.

Figure 10.

Arm-extension wall slides to facilitate proper scapular retraction and posterior tilting.

Closed kinetic chain exercises are advanced during the intermediate phase. Weight shifting on a ball progresses to a push-up on a ball or an unstable surface on a table top. Rhythmic stabilizations of the upper extremity, uninvolved shoulder, and trunk are performed with the rehabilitation specialist (Figure 11). Wall stabilization drills can be performed with the athlete’s hand on a small ball (Figure 12). Additional axial compression exercises include table and quadruped, using a towel around the hand, slide board, or unstable surface.

Figure 11.

Transitioning weightbearing rhythmic stabilization exercises to nonweightbearing positions simulating the landing (A), arm-cocking (B), and ball-release (C) phases of the throwing motion.

Figure 12.

Rhythmic stabilization drills in the 90° abducted and 90° external rotation position on an unstable surface in the closed kinetic chain position against the wall.

Advanced Phase

The third phase of the rehabilitation program prepares the athlete to return to athletic activity. Criteria to enter this phase include minimal pain and tenderness, full range of motion, symmetrical capsular mobility, good strength (at least 4/5 on manual muscle testing), upper extremity and scapulothoracic endurance, and sufficient dynamic stabilization.

Full motion and posterior muscle flexibility should be maintained throughout this phase. Exercises such as IR and ER with exercise tubing at 90° of abduction progress to incorporate eccentric and high-speed contractions.

Aggressive strengthening of the upper body may also be initiated depending on the needs of the individual patient. Common exercises include isotonic weight machine bench press, seated row, and latissimus dorsi pull-downs within a restricted range of motion. During bench press and seated row, the athlete should not extend the arms beyond the plane of the body, to minimize stress on the shoulder capsule. Latissimus pull-downs are performed in front of the head while the athlete avoids full extension of the arms to minimize traction force on the upper extremities.

Plyometrics for the upper extremity may be initiated during this phase to train the upper extremity to dissipate forces. The chest pass, overhead throw, and alternating side-to-side throw with a 3- to 5-lb (1.6- to 2.3-kg) medicine ball are initially performed with 2 hands. Two-hand drills progress to 1-hand drills over 10 to 14 days. One-hand plyometrics include baseball-style throws in the 90/90 position (90° of abduction and 90° of ER) with a 2-lb (0.9-kg) ball, deceleration flips (Figure 13), and stationary and semicircle wall dribbles. Wall dribbles progress to the 90/90 position. They are beneficial for upper extremity endurance while overhead.

Figure 13.

Plyometric deceleration ball flips. The patient catches the ball over the shoulder and decelerates the arm (similar to the throwing motion) before flipping back and returning to the starting position.

Dynamic stabilization and neuromuscular control drills should be reactive, functional, and in sport-specific positions. Concentric and eccentric manual resistance may be applied as the athlete performs ER with exercise tubing, with the arm at 0° abduction. Rhythmic stabilizations may be included at end range, to challenge the athlete to stabilize against the force of the tubing as well as the therapist, and may progress to the 90/90 position (Figure 14). Rhythmic stabilizations may also be applied at end range during the 90/90 wall-dribble exercise. These drills are designed to impart a sudden perturbation to the throwing shoulder near end range to develop the athlete’s ability to dynamically stabilize the shoulder.

Figure 14.

Rhythmic stabilization drills during exercise tubing at 90° of abduction and 90° of external rotation (A) and during wall dribbles (B).

Muscle endurance exercises should be emphasized because the overhead athlete is at greater risk for shoulder and/or elbow injuries when pitching fatigued.34 Endurance drills include wall dribbling, ball flips (Figure 15), wall arm circles, upper-body cycle, or isotonic exercises using lower weights for higher repetitions. Murray et al42 demonstrated the effects of fatigue on the entire body during pitching using kinematic and kinetic motion analysis. Once the thrower is fatigued, shoulder ER decreases ball velocity and leads to lower extremity knee flexion, and shoulder adduction torque decreases. Muscle fatigue also affects proprioception.67 Once the rotator cuff muscles are fatigued, the humeral head migrates superiorly when arm elevation is initiated.11 Muscle fatigue was the predisposing factor that correlated best with shoulder injuries in Little League pitchers.34 Thus, endurance drills appear critical for the overhead thrower.

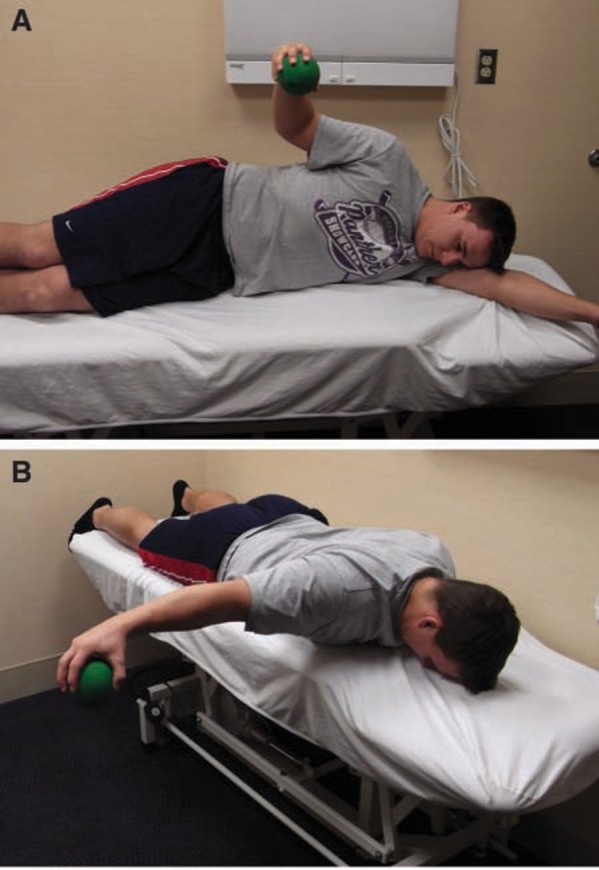

Figure 15.

Ball flips for endurance of the external rotators (A) and scapular retractors (B).

Return-to-Activity Phase

Upon completion of the rehabilitation program—including minimal pain or tenderness, full range of motion, balanced capsular mobility, adequate proprioception, and dynamic stabilization—the athlete may begin the return-to-activity phase.

The return to throwing starts with a long-toss program (Appendix 1, available at http://sph.sagepub.com/supplemental) designed to increase distance and number of throws.55 Athletes typically begin at 30 to 45 ft (9 to 14 m) and progress to 60, 90, and 120 ft (18, 27, and 37 m). Pitchers begin a mound throwing program (Appendix 2, available at http://sph.sagepub.com/supplemental), whereas positional players progress to greater distances of long-toss and positional drills. Throwing off the mound includes a gradual increase in the number and intensity of effort and, finally, type of pitch. A player will typically throw 3 times a week with a day off in between, performing each step 2 or 3 times before progressing.

The interval throwing program is supplemented with a high-repetition, low-resistance maintenance exercise program for the rotator cuff and scapula. All strengthening, plyometric, and neuromuscular control drills should be performed 3 times per week (with a day off in between) on the same day as the ISP. The athlete should warm up, stretch, and perform 1 set of each exercise before the interval sport program, followed by 2 sets of each exercise after the program. This provides an adequate warm-up but ensures maintenance of necessary range of motion and flexibility of the upper extremity.

Nonthrowing days are used for lower extremity, cardiovascular, core stability training, range of motion, and light strengthening exercises emphasizing the posterior rotator cuff and scapular muscles. The cycle is repeated throughout the week with the seventh day designated for rest, light range of motion, and stretching exercises.

Internal Posterosuperior Glenoid Impingement

Posterosuperior glenoid impingement (internal impingement) is one of the most frequently observed conditions in the overhead throwing athlete,# and may be caused by excessive anterior shoulder laxity.51 The primary goal of the rehabilitation program is to enhance dynamic stabilization to control anterior humeral head translation while restoring flexibility to the posterior rotator cuff muscles. A careful approach is warranted because aggressive stretching of the anterior and inferior glenohumeral structures may result in increased anterior translation.

The scapular musculature—specifically, the middle trapezius and lower trapezius—is an area of special focus. Once the thrower begins the interval throwing program, the clinician or pitching coach should frequently observe the athlete’s throwing mechanics. Throwers with internal impingement occasionally allow their arms to lag behind the scapula (excessive horizontal abduction). This hyperangulation of the arm may lead to excessive strain on the anterior capsule and internal impingement of the posterior rotator cuff.21,22,51,55,69 The best treatment for internal impingement is a nonoperative program.

Subacromial Impingement

Primary subacromial impingement in the young overhead throwing athlete is unusual22,37 but may occur with primary hyperlaxity or loss of dynamic stability.22

The nonoperative treatment is similar to that of internal impingement, emphasizing scapular strengthening. Impingement patients exhibit less posterior tilting than do those without impingement.32 The rehabilitation program should include pectoralis minor stretching, inferior trapezius strengthening to ensure posterior scapular tilting, and minimizing forward head posture. Excessive scapular protraction produces anterior scapular tilt and diminishes the acromial-humeral space, whereas scapular retraction increases it.63

Subacromial impingement can be treated conservatively with or without a subacromial injection. The injection is used to relieve pain and inflammation, which in turn allows the patient to more effectively perform a therapy program after a period of rest.

Overuse Syndrome Tendinitis

Throwers may exhibit the signs of overuse tendinitis in the rotator cuff and/or long head of the biceps brachii muscles,4,23,37,49 especially early in the season, when the athlete’s arm may not be in optimal condition.

The thrower will often complain of bicipital pain, referred to as groove pain. The biceps brachii appears to be moderately active during the overhead throwing motion. Bicipital tendinitis usually represents a secondary condition in the overhead thrower. The primary disorder may be instability, a superior labral anterior posterior (SLAP) lesion, or other pathology. The rehabilitation of this condition focuses on improving dynamic stabilization of the glenohumeral joint through muscular training drills. A glenohumeral joint capsule–biceps reflex is present in the feline.19,28 Investigators demonstrated that the biceps brachii was the first muscle to respond to stimulation of the capsule (2.7 milliseconds). The biceps brachii may be activated to a greater extent when the thrower exhibits hyperlaxity or inflammation of the capsule. Nonoperative rehabilitation usually consists of a reduction in throwing activities, the reestablishment of dynamic stability and modalities to reduce bicipital inflammation.

Posterior Rotator Cuff Tendinitis

The successful treatment of rotator cuff tendinitis depends on its differentiation from internal impingement. Subjectively, the athlete notes posterior shoulder pain during ball release or the deceleration phase of throwing. In athletes with internal impingement, the pain occurs during late cocking and early acceleration. During throwing, excessive forces must be dissipated and opposed by the rotator cuff muscles.17 There is often significant weakness of the infraspinatus, lower trapezius, and middle trapezius, as well as tightness of the external rotators.

Once strength levels have improved, eccentric muscle training should be emphasized for the external rotators and lower trapezius (Figure 16). Electromyographic activity in the teres minor is 84% maximal voluntary contraction and 78% maximal voluntary contraction in the lower trapezius, during the deceleration phase of a throw and should thus be the focus of the strengthening program.14

Figure 16.

Manual-resistance eccentric contraction of the lower trapezius.

Acquired Microinstability

The anterior capsule undergoes significant tensile stress in the late cocking and early acceleration phases of the throwing motion. This stress can lead to gradual stretching of the capsular collagen over time, leading to increased anterior capsular laxity. Several authors25,26,29,30,69 have proposed that repetitive strain on the anterior capsule causes anterior capsular laxity and may worsen internal impingement. Reinold and Gill (unpublished data, 2009) noted that professional baseball pitchers exhibit an increase of 5° of ER at the end of a season in comparison to preseason measurements despite the avoidance of aggressive stretching.49

Mihata et al40 demonstrated in the cadaveric model that excessive ER results in elongation of the anterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament complex and an increase in anterior and inferior translation. Anterior displacement may cause the undersurface of the rotator cuff musculature to impinge on the posterosuperior glenoid rim.

Several arthroscopic procedures (capsular plication and thermal capsular shrinkage) have been developed in an attempt to reduce capsular laxity without overconstraining the joint.5,30,33,47 Rehabilitation following these procedures is designed to gradually restore motion, strength, and neuromuscular control.53,71 Immediately following surgery, restricted passive motion is allowed but not overaggressive stretching. Excessive ER, elevation, or extension is not allowed. By week 6, 75° of ER is the goal. By week 8, 90° of ER at 90° of abduction should be achieved. Usually between weeks 6 and 8, flexion is 170° to 180°. In the case of the overhead athlete—particularly, the pitcher—ER to 115° is needed. This is usually achieved gradually, no earlier than week 12. The athlete is not stretched aggressively past 115° to 120° of ER. Rather, the athlete regains “normal” motion through functional activities within the rehabilitation program, such as plyometrics. The lack of full ER in the overhead athlete is a common cause of symptoms during rehabilitation and throwing.

Isometrics begin in the first 7 to 10 days in a submaximal, nonpainful manner. At approximately 10 to 14 days postoperatively, a light isotonic program begins emphasizing ER and scapular strengthening. At week 5, the athlete is allowed to progress to the full rotator cuff and scapula exercise program with plyometrics at 8 weeks using 2 hands and restricting ER. After 10 to 14 days, 1-hand drills begin. An aggressive strengthening program is allowed at week 12 and is adjusted according to the patient’s response. A gradual return to throwing is expected at week 16, with a return to overhead sports by 9 to 12 months.55

SLAP Lesions

SLAP lesions involve detachment of glenoid labrum–biceps complex from the glenoid rim. These injuries occur through a variety of mechanisms, including falls, traction, motor vehicle accidents, and sports.72 Overhead throwing athletes commonly present with a type II SLAP lesion with the biceps tendon detached from the glenoid rim and a peel back lesion.10

Conservative management of SLAP lesions is often unsuccessful—particularly, type II and type IV lesions with labral instability and underlying shoulder instability. With surgical repair, the initial rehabilitative concern is to ensure that forces on the repaired labrum are controlled. The extent of the lesion, its location, and number of suture anchors are considered when developing a rehabilitation program. The patient sleeps in a shoulder immobilizer and wears a sling during the day for the first 4 weeks following surgery. Range of motion is performed below 90° of elevation to avoid strain on the labral repair. During the first 2 weeks, IR and ER range of motion exercises are performed passively in the scapular plane (15° of ER and 45° of IR). Initial ER range of motion is performed cautiously to minimize strain on the labrum. At 4 weeks postoperative, the patient begins IR and ER range of motion activities at 90° of shoulder abduction. Flexion can be performed above 90° of elevation. Motion is gradually increased to restore full range of motion (90° to 100° of ER at 90° of abduction) by 8 weeks and progresses to thrower’s motion (115° to 120° of ER) through week 12.

Isometric exercises are performed submaximally immediately postoperatively to prevent atrophy. Biceps contractions are not permitted for 8 weeks following repair. ER/IR exercise tubing is initiated at week 3 or 4 and so progresses to include lateral raises, full can, prone rowing, and prone horizontal abduction by week 6. A full isotonic exercise program for the rotator cuff and scapulothoracic musculature is initiated by week 7 or 8.

Resisted biceps activity (elbow flexion and forearm supination) is not allowed for the first 8 weeks to protect healing of the biceps anchor. Aggressive strengthening of the biceps is avoided for 12 weeks following surgery. Weightbearing exercises are not performed for at least 8 weeks to avoid compression and shearing forces on the healing labrum. Two-hand plyometrics, as well as more advanced strengthening activities, are allowed between 10 and 12 weeks, progressing to an interval sport program at week 16. Return to play following the surgical repair of a type II SLAP lesion typically occurs at approximately 9 to 12 months following surgery.

Conclusion

The overhead athlete can present with several different pathologies owing to forces acting during throwing. Care of these patients requires a thorough understanding of the unique physical characteristics of this population. Rehabilitation should follow a gradual and sequential progression. Injury prevention and rehabilitation programs should both emphasize range of motion, flexibility, rotator cuff and scapula strength, posture, and dynamic stabilization. Programs should be individualized per time of season, level of play, and type of injury.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest declared.

NATA Members: Receive 3 free CEUs each year when you subscribe to Sports Health and take and pass the related online quizzes! Not a subscriber? Not a member? The Sports Health–related CEU quizzes are also available for purchase. For more information and to take the quiz for this article, visit www.nata.org/sportshealthquizzes.

References

- 1. Andrews JR, Angelo RL. Shoulder arthroscopy for the throwing athlete. Tech Orthop. 1988;3:75-79 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Andrews JR, Broussard TS, Carson WG. Arthroscopy of the shoulder in the management of partial tears of the rotator cuff: a preliminary report. Arthroscopy. 1985;1(2):117-122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Andrews JR, Kupferman SP, Dillman CJ. Labral tears in throwing and racquet sports. Clin Sports Med. 1991;10(4):901-911 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Andrews JR, Timmerman LA, Wilk KE. Baseball. In: Pettrone FA, ed. Athletic Injuries of the Shoulder. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bigliani LU, Kurzweil PR, Schwartzbach CC, Wolfe IN, Flatow EL. Inferior capsular shift procedure for anterior-inferior shoulder instability in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(5):578-584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blackburn TA, McLeod WD, White B. Electromyographic analysis of posterior rotator cuff exercises. J Athl Train. 1990;25:40-45 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Borich MR, Bright JM, Lorello DJ, Cieminski CJ, Buisman T, Ludewig PM. Scapular angular positioning at end range internal rotation in cases of glenohumeral internal rotation deficit. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36(12):926-934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Borsa PA, Dover GC, Wilk KE, Reinold MM. Glenohumeral range of motion and stiffness in professional baseball pitchers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(1):21-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Borsa PA, Wilk KE, Jacobson JA, et al. Correlation of range of motion and glenohumeral translation in professional baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(9):1392-1399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burkhart SS, Morgan CD. The peel-back mechanism: its role in producing and extending posterior type II SLAP lesions and its effect on SLAP repair rehabilitation. Arthroscopy. 1998;14(6):637-640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen SK, Wickiewicz TL, Otis JC. Glenohumeral kinematics in a muscle fatigue model. Orthop Trans. 1995;18:1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davies GJ, Dickoff-Hoffman S. Neuromuscular testing and rehabilitation of the shoulder complex. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;18(2):449-458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Decker MJ, Hintermeister RA, Faber KJ, Hawkins RJ. Serratus anterior muscle activity during selected rehabilitation exercises. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(6):784-791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. DiGiovine NM, Jobe FW, Pink M. An electromyographic analysis of the upper extremity in pitching. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1992;1:15-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dugas JR, Andrews JR. Throwing injuries in the adult. In: DeLee JC, Drez D, Miller MD, eds. DeLee and Drez’s Orthopaedic Sports Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Science; 2003:1236-1249 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ellenbecker TS. Rehabilitation of shoulder and elbow injuries in tennis players. Clin Sports Med. 1995;14(1):87-110 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Dillman CJ, Escamilla RF. Kinetics of baseball pitching with implications about injury mechanisms. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(2):233-239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fleisig GS, Barrentine SW, Escamilla RF, Andrews JR. Biomechanics of overhand throwing with implications for injuries. Sports Med. 1996;21(6):421-437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guanche C, Knatt T, Solomonow M, Lu Y, Baratta R. The synergistic action of the capsule and the shoulder muscles. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(3):301-306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heiderscheit BC, McLean KP, Davies GJ. The effects of isokinetic vs. plyometric training on the shoulder internal rotators. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1996;23(2):125-133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jobe CM. Posterior superior glenoid impingement: expanded spectrum. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(5):530-536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jobe CM. Superior glenoid impingement: current concepts. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;330:98-107 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jobe FW. Impingement problems in the athlete. Instr Course Lect. 1989;38:205-209 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jobe FW, Bradley JP. Rotator cuff injuries in baseball: prevention and rehabilitation. Sports Med. 1988;6(6):378-387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jobe FW, Giangarra CE, Kvitne RS, Glousman RE. Anterior capsulolabral reconstruction of the shoulder in athletes in overhand sports. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(5):428-434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jobe FW, Kvitne RS, Giangarra CE. Shoulder pain in the overhand or throwing athlete: the relationship of anterior instability and rotator cuff impingement. Orthop Rev. 1989;18(9):963-975 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jobe FW, Pink M. Classification and treatment of shoulder dysfunction in the overhead athlete. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;18(2):427-432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Knatt T, Guanche C, Solomonow M, Lu Y, Baratta R, Zhou BH. The glenohumeral-biceps reflex in the feline. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;314:247-252 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kvitne RS, Jobe FW. The diagnosis and treatment of anterior instability in the throwing athlete. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;291:107-123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kvitne RS, Jobe FW, Jobe CM. Shoulder instability in the overhand or throwing athlete. Clin Sports Med. 1995;14(4):917-935 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Levitz CL, Dugas J, Andrews JR. The use of arthroscopic thermal capsulorrhaphy to treat internal impingement in baseball players. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(6):573-577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lukasiewicz AC, McClure P, Michener L, Pratt N, Sennett B. Comparison of 3-dimensional scapular position and orientation between subjects with and without shoulder impingement. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1999;29(10):574-583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lusardi DA, Wirth MA, Wurtz D, Rockwood CA. Loss of external rotation following anterior capsulorrhaphy of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75(8):1185-1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lyman S, Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Osinski ED. Effect of pitch type, pitch count, and pitching mechanics on risk of elbow and shoulder pain in youth baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(4):463-468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Matveyev LP. Perodisienang das sportlichen training. Berlin: Beles & Wernitz; 1972 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mazoue CG, Andrews JR. Repair of full-thickness rotator cuff tears in professional baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(2):182-189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Meister K. Injuries to the shoulder in the throwing athlete. Part one: biomechanics/pathophysiology/classification of injury. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(2):265-275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Meister K. Injuries to the shoulder in the throwing athlete. Part two: evaluation/treatment. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(4):587-601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Meister K. Internal impingement in the shoulder of the overhand athlete: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Orthop. 2000;29(6):433-438 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mihata T, Lee Y, McGarry MH, Abe M, Lee TQ. Excessive humeral external rotation results in increased shoulder laxity. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(5):1278-1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moseley JB, Jobe FW, Pink M, Perry J, Tibone J. EMG analysis of the scapular muscles during a shoulder rehabilitation program. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20(2):128-134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Murray TA, Cook TD, Werner SL, Schlegel TF, Hawkins RJ. The effects of extended play on professional baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(2):137-142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Myers JB, Laudner KG, Pasquale MR, Bradley JP, Lephart SM. Glenohumeral range of motion deficits and posterior shoulder tightness in throwers with pathologic internal impingement. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(3):385-391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nuber GW, McCarthy WJ, Yao JS, Schafer MF, Suker JR. Arterial abnormalities of the shoulder in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18(5):514-519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Poppen NK, Walker PS. Forces at the glenohumeral joint in abduction. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1978;135:165-170 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Prokopy MP, Ingersoll CD, Nordenschild E, Katch FI, Gaesser GA, Weltman A. Closed-kinetic chain upper-body training improves throwing performance of NCAA Division I softball players. J Strength Cond Res. 2008;22(6):1790-1798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Protzman RR. Anterior instability of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62(6):909-918 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Reinold MM, Escamilla RF, Wilk KE. Current concepts in the scientific and clinical rationale behind exercises for glenohumeral and scapulothoracic musculature. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39(2):105-117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Reinold MM, Gill TJ. Current concepts in the evaluation and treatment of the shoulder in overhead throwing athletes: Part 1: Physical characteristics and clinical examination. Sports Health. 2010;2:39-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Reinold MM, Macrina LC, Wilk KE, et al. Electromyographic analysis of the supraspinatus and deltoid muscles during 3 common rehabilitation exercises. J Athl Train. 2007;42(4):464-469 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Reinold MM, Wilk KE, Dugas JR, Andrews JR. Internal Impingement. In: Wilk KE, Reinold MM, Andrews JR, eds. The Athletes Shoulder. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingston Elsevier; 2009:123-142 [Google Scholar]

- 52. Reinold MM, Wilk KE, Fleisig GS, et al. Electromyographic analysis of the rotator cuff and deltoid musculature during common shoulder external rotation exercises. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34(7):385-394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Reinold MM, Wilk KE, Hooks TR, Dugas JR, Andrews JR. Thermal-assisted capsular shrinkage of the glenohumeral joint in overhead athletes: a 15- to 47-month follow-up. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33(8):455-467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Reinold MM, Wilk KE, Macrina LC, et al. Changes in shoulder and elbow passive range of motion after pitching in professional baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(3):523-527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Reinold MM, Wilk KE, Reed J, Crenshaw K, Andrews JR. Interval sport programs: guidelines for baseball, tennis, and golf. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2002;32(6):293-298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rohrer MJ, Cardullo PA, Pappas AM, Phillips DA, Wheeler HB. Axillary artery compression and thrombosis in throwing athletes. J Vasc Surg. 1990;11(6):761-768 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ruotolo C, Price E, Panchal A. Loss of total arc of motion in collegiate baseball players. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(1):67-71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Salter RB, Bell RS, Keeley FW. The protective effect of continuous passive motion in living articular cartilage in acute septic arthritis: an experimental investigation in the rabbit. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1981;159:223-247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Salter RB, Hamilton HW, Wedge JH, et al. Clinical application of basic research on continuous passive motion for disorders and injuries of synovial joints: a preliminary report of a feasibility study. J Orthop Res. 1984;1(3):325-342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Salter RB, Simmonds DF, Malcolm BW, Rumble EJ, MacMichael D, Clements ND. The biological effect of continuous passive motion on the healing of full-thickness defects in articular cartilage: an experimental investigation in the rabbit. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62(8):1232-1251 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Scarpinato DF, Bramhall JP, Andrews JR. Arthroscopic management of the throwing athlete’s shoulder: indications, techniques, and results. Clin Sports Med. 1991;10(4):913-927 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Schulte-Edelmann JA, Davies GJ, Kernozek TW, Gerberding ED. The effects of plyometric training of the posterior shoulder and elbow. J Strength Cond Res. 2005;19(1):129-134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Solem-Bertoft E, Thuomas KA, Westerberg CE. The influence of scapular retraction and protraction on the width of the subacromial space: an MRI study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;296:99-103 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sotta RP. Vascular problems in the proximal upper extremity. Clin Sports Med. 1990;9(2):379-388 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Thigpen CA, Reinold MM, Padua DA, Schneider RS, Distefano LJ, Gill TJ. 3-D scapular position and muscle strength are related in professional baseball pitchers. J Athl Train. 2008;43(2):S49 [Google Scholar]

- 66. Townsend H, Jobe FW, Pink M, Perry J. Electromyographic analysis of the glenohumeral muscles during a baseball rehabilitation program. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(3):264-272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Voight ML, Hardin JA, Blackburn TA, Tippett S, Canner GC. The effects of muscle fatigue on and the relationship of arm dominance to shoulder proprioception. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1996;23(6):348-352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Walker PS, Poppen NK. Biomechanics of the shoulder joint during abduction in the plane of the scapula [proceedings]. Bull Hosp Joint Dis. 1977;38(2):107-111 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wilk KE, Meister K, Andrews JR. Current concepts in the rehabilitation of the overhead throwing athlete. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(1):136-151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wilk KE, Reinold MM, Andrews JR. Rehabilitation of the thrower’s elbow. Clin Sports Med. 2004;23(4):765-801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wilk KE, Reinold MM, Dugas JR, Andrews JR. Rehabilitation following thermal-assisted capsular shrinkage of the glenohumeral joint: current concepts. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2002;32(6):268-292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wilk KE, Reinold MM, Dugas JR, Arrigo CA, Moser MW, Andrews JR. Current concepts in the recognition and treatment of superior labral (SLAP) lesions. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005;35(5):273-291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wilk KE, Voight ML, Keirns MA, Gambetta V, Andrews JR, Dillman CJ. Stretch-shortening drills for the upper extremities: theory and clinical application. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;17(5):225-239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Worrell TW, Corey BJ, York SL, Santiestaban J. An analysis of supraspinatus EMG activity and shoulder isometric force development. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1992;24(7):744-748 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]