Abstract

We developed a new molecular tool based on rpoB gene (encoding the beta subunit of RNA polymerase) sequencing to identify streptococci. We first sequenced the complete rpoB gene for Streptococcus anginosus, S. equinus, and Abiotrophia defectiva. Sequences were aligned with these of S. pyogenes, S. agalactiae, and S. pneumoniae available in GenBank. Using an in-house analysis program (SVARAP), we identified a 740-bp variable region surrounded by conserved, 20-bp zones and, by using these conserved zones as PCR primer targets, we amplified and sequenced this variable region in an additional 30 Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Gemella, Granulicatella, and Abiotrophia species. This region exhibited 71.2 to 99.3% interspecies homology. We therefore applied our identification system by PCR amplification and sequencing to a collection of 102 streptococci and 60 bacterial isolates belonging to other genera. Amplicons were obtained in streptococci and Bacillus cereus, and sequencing allowed us to make a correct identification of streptococci. Molecular signatures were determined for the discrimination of closely related species within the S. pneumoniae-S. oralis-S. mitis group and the S. agalactiae-S. difficile group. These signatures allowed us to design a S. pneumoniae-specific PCR and sequencing primer pair.

Aerobic, gram-positive, catalase-negative cocci were initially regarded as forming an unique phylum of bacteria roughly corresponding to the genus Streptococcus (41). Broad changes in the classification of the streptococci have resulted from molecular taxonomic studies of the genus Streptococcus. The enterococci, previously considered group D streptococci, now reside in their own genus, Enterococcus (44). A new genus, Abiotrophia, has been proposed to accommodate nutritionally variant streptococci (21). Finally, Collins and Lawson have proposed that three species of the genus Abiotrophia be reclassified into a new genus, Granulicatella (9).

These new genera accommodate bacterial isolates recovered from environmental and clinical sources (41). In humans, streptococci are responsible for a wide range of manifestations, including both invasive and toxin-related manifestations such as scarlet fever (1). Streptococcus agalactiae is the leading cause of neonatal disease, requiring urgent diagnosis in pregnant women (31). S. pneumoniae is the bacterial species most frequently isolated in cerebrospinal fluid from individuals with adult meningitis (27). It requires rapid detection, even in the case of culture-negative meningitis due to antibiotic treatment. Also, microorganisms of these five genera remain the leading cause of infective endocarditis worldwide, a life-threatening condition requiring rapid antibiotic treatment based on effective identification of the causing species. Also, because some species are fastidious and highly susceptible to antibiotics, these are responsible for blood culture-negative endocarditis. Emerging taxons of streptococci have been described in this situation such as S. sinensis (51), S. pasteurianus (37), S. lutetiensis (37), Enterococcus hirae (38), and Granulicatella elegans (7). Recent reappraisal of these taxons demonstrated that S. lutetiensis was a genotype of S. infantarius and that S. pasteurianus was a subspecies of S. gallolyticus (45). In these situations also, molecular detection and identification of the causative agent should be done even after antibiotic treatment resulted in culture-negative endocarditis.

In clinical laboratories, the current means of identification of streptococci and related genera rely on phenotypic tests, such as those developed into the API ID 32 Strep system (Bio Mérieux, la Balme les Grottes, France). However, the potential problems inherent in the use of phenotypic tests are that not all strains within a given species may be positive for a common trait (3, 24) and that the same strain may exhibit biochemical variability (19, 48). Consequently, the routine technique based on phenotypic tests does not allow for an unequivocal identification of certain streptococcal species, in particular those belonging to the S. milleri, the S. mutans and the S. mitis groups (3, 14, 24).

Nucleic acid probes have been developed for the identification of isolates of group A and B streptococci (10, 18). For the identification of S. pneumoniae, a commercial probe has been increasingly used (11, 16), and different PCR-based methods detected genes for pneumococcal toxins or other virulence factors, such as the pneumolysin (ply) (42) and the major autolysin (lytA) not normally present in other alpha-hemolytic streptococci (20, 33, 43). Also, PCR-based techniques targeted the streptococcal 16S-23S rRNA spacer region (15), the C protein gene of S. agalactiae (5, 29), the groESL genes of viridans group streptococci (49), and sodA gene encoding the manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase in several Streptococcus and Enterococcus species (34, 35, 36) by using two different pairs of primers. However, no molecular tool comprised these five genera at one time, with the exception of 16S rRNA gene, which did not discriminate all species (4).

rpoB, the gene encoding the highly conserved subunit of the bacterial RNA polymerase, has previously been demonstrated to be a suitable target on which to base the identification of enteric bacteria (30), spirochetes (28, 41), bartonellas (40), rickettsias (13), legionellae (26), mycobacteria (17, 25), staphylococci (12), Bacillus spp. (39), and ehrlichiae (47). The gene has been shown to be more discriminative than the 16S rRNA gene (30) for identifying enteric bacteria. In this report, we describe the molecular identification of aerobic, gram-positive catalase-negative species of the genera Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Gemella, Abiotrophia, and Granulicatella by using a single specific primer pair for PCR and sequencing method based on the sequence of the rpoB gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The 33 streptococcal type strains used in the present study are listed in Table 1. They were grown on blood agar at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere. All isolates were streaked on blood agar plates to determine the purity of each of the cultures by macroscopic examination of colonies and microscopic examination of Gram-stained preparations. Colonies were scraped from the plates and boiled for 15 min in Chelex 100 (46) and 1% sodium docecyl sulfate solution (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) before genomic DNA was extracted and purified with QIAmp DNA minikits (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). The 162 clinical isolates used in blind identification testing (see below) are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

List of 33 streptococcus species investigated by rpoB sequencing

| Species | CIP straina | GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|

| Abiotrophia defectiva | 103242T | AF535173 |

| Enterococcus avium | 103019T | AF535192 |

| Enterococcus casselliflavus | 103018T | AF535174 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 103015T | AF535178 |

| Enterococcus faecium | 103014T | AF535176 |

| Enterococcus gallinarum | 103013T | AF535177 |

| Enterococcus saccharolyticus | 103246T | AF535175 |

| Gemella haemolysans | 101126T | AF535179 |

| Gemella morbillorum | 81.10T | AF535180 |

| Granulicatella adjacens | 103243T | AF535172 |

| Streptococcus acidominimus | 82.4T | AF535181 |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 103227T | AF535182 |

| Streptococcus anginosus | 103244T | AF535183 |

| Streptococcus bovis | 102302T | AF535189 |

| Streptococcus constellatus | 103247T | AF535184 |

| Streptococcus difficile | 103768T | AF535191 |

| Streptococcus dysgalactiae | 102914T | AF535185 |

| Streptococcus equi | 102910T | AF535186 |

| Streptococcus gallolyticus | 105428T | AY315154 |

| Streptococcus equinus | 102504T | AF535187 |

| Streptococcus infantarius | 103233T | AY315155 |

| Streptococcus intermedius | 103248T | AF535190 |

| Streptococcus lutetientis | 106849T | AY315158 |

| Streptococcus macedonicus | 105683T | AY315156 |

| Streptococcus mitis | 103335T | AF535188 |

| Streptococcus mutans | 103220T | AF535167 |

| Streptococcus oralis | 102922T | AF535168 |

| Streptococcus pasteurianus | 107122T | AY315157 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 10291T | AE008542 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 56.41T | AE006480 |

| Streptococcus salivarius | 102503T | AF535169 |

| Streptococcus sanguinis | 55.128T | AF535170 |

| Streptococcus suis | 103217T | AF535171 |

CIP, Institut Pasteur Collection, Paris, France.

TABLE 2.

List of 162 bacterial clinical isolates used for blind identification testing by the rpoB gene sequence-based method described in the text

| Species | No. of isolates | Species | No. of isolates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abiotrophia defectiva | 2 | |||

| Acinetobacter baumanii | 1 | |||

| Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans | 1 | |||

| Actinomyces spp. | 3 | |||

| Aeromonas hydrophila | 1 | |||

| Arcanobacterium haemolyticum | 1 | |||

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 1 | |||

| Bacillus cereus | 3 | |||

| Borrelia burgdorferi | 1 | |||

| Campylobacter fetus | 1 | |||

| Candida albicans | 2 | |||

| Clostridium spp. | 3 | |||

| Corynebacterium spp. | 5 | |||

| Coxiella burnetii | 1 | |||

| Escherichia coli | 2 | |||

| Eikenella corrodens | 1 | |||

| Enterobacter agglomerans | 3 | |||

| Enterococcus casselliflavus | 1 | |||

| Enterococcus faecalis | 12 | |||

| Enterococcus faecium | 11 | |||

| Enterococcus gallinarum | 2 | |||

| Gemella haemolyticus | 3 | |||

| Gemella morbillorum | 1 | |||

| Granulicatella adjacens | 1 | |||

| Haemophilus influenza | 1 | |||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 1 | |||

| Kluyvera ascorbata | 1 | |||

| Lactobacillus spp. | 2 | |||

| Legionella pneumophila | 1 | |||

| Leuconostoc lactis | 1 | |||

| Moraxella lacunata | 1 | |||

| Mycobacterium spp. | 5 | |||

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 1 | |||

| Norcardia asteroides | 1 | |||

| Neisseria meningitidis | 1 | |||

| Pasteurella multocida | 1 | |||

| Pediococcus acidilactici | 1 | |||

| Peptostreptococcus magnus | 1 | |||

| Propionibacterium acnes | 3 | |||

| Serratia marcescens | 1 | |||

| Staphylococcus spp. | 5 | |||

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 7 | |||

| Streptococcus anginosus | 5 | |||

| Streptococcus bovis | 2 | |||

| Streptococcus constellatus | 1 | |||

| Steptococcus equinus | 1 | |||

| Streptococcus gordonii | 1 | |||

| Streptococcus infantarius | 1 | |||

| Streptococcus intermedius | 4 | |||

| Streptococcus mitis | 8 | |||

| Streptococcus oralis | 7 | |||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 12 | |||

| Streptococcus salivarius | 1 | |||

| Streptococcus sanguis | 2 | |||

| Turicella otitidis | 1 |

Determination of the complete rpoB sequence in S. equinus, S. anginosus, and Abiotrophia defectiva.

Consensus rpoB PCR primers were designed after the alignment of rpoB genes of S. pyogenes (GenBank accession number AE006480), S. pneumoniae (GenBank accession number AE008542), and Bacillus subtilis (GenBank accession number L43593) and numbered on the basis of the S. agalactiae rpoB sequence (Table 3). Primer pair 31F (5′-GCCTTAGGACCTGGTGGTTT-3′)-830R (5′-GTTGTAACCTTCCAWGTCAT-3′) was used to amplify a rpoB gene fragment in S. equinus, S. anginosus, and A. defectiva. These species were chosen as representatives of the major phyla based on analysis of the phylogenetic tree derived from the 16S rRNA sequencing. Additional oligonucleotides were selected on the basis of data obtained from ongoing base sequence determination (Table 2). The forward primers 371F, 730F, and 1848F combined with the reverse primers 585R, 1252R, 2057R, and 2215R were used to amplify and sequence additional portions of the rpoB gene in these three species. All PCR mixtures contained 2.5 × 102 U of Taq polymerase/μl, 1× Taq buffer, 1.8 mM MgCl2 (Gibco-BRL/Life Technologies, Cergy Pontoise, France), 200 μM concentrations of dATP, dTTP, dGTP, and dCTP (Boehringer Manheim GmbH, Hilden, Germany), and 0.2 μM concentrations of each primer (Eurogentec, Serraing, Belgium). PCR mixtures were subjected to 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, primer annealing at 52°C for 30 s, and de novo DNA extension at 72°C for 60 s. Every amplification program began with a denaturation step of 95°C for 2 min and ended with a final elongation step of 72°C for 5 min. Amplicons were purified for sequencing by using a QIAquick spin PCR purification kit (Qiagen) according to the protocol of the supplier. The sequences of the 3′ and 5′ extremities were determined by using the universal Genomic Walker kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.), incorporating primers 520R and 2881F and primers 1000R and 3000F for E. faecalis.

TABLE 3.

Primers used to sequence the entire rpoB gene in S. anginosus, S. equinus, and A. defectiva

| Sequence (5′-3′) | Primer

|

Tm (°C) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | ||

| GCCTTAGGACCTGGTGGTTT | 31F | 58 | |

| CGTTGCATGTTGGCACCCAT | 503R | 58 | |

| GGACACATACGACCATAGTG | 116R | 56 | |

| AGACGGACCTTCTATGGAAAA | StrpoB 748F | 56 | |

| GTTGTAACCTTCCCAWGTC AT | 830R | 56 | |

| AACCAATTCCGYATYGGTYT | 1252F | 53 | |

| GTCTTCWTGGGYGATTTCCC | 2215F | 57 | |

| ACCGTGGiGCWTGGTTRGAAT | 205F | 56 | |

| AGTGCCCAAACCTCCATCTC | 730F | 56 | |

| AGTGGGTTTAACATGATGTC | 371F | 50 | |

| CTCCAAGTGAACAGATGTGTA | 585R | 56 | |

| AACCAAGCYCCACGGTTAGGRAT | GW520R | 64 | |

| ATGTTGAACCCACTiGGGGTGCCAT | GW2881F | 64 | |

| TGTArTTTrTCATCAACCATGTG | Strepto R | 52 | |

| AARYTiGGMCCTGAAGAAAT | Strepto F | 52 | |

| CTTTACGATGGACGTACAGGTGAACCATTT | 3000F | 66 | |

| GCTGTCGTCTGGATAGCCGTTACCAAT | 1000R | 67 | |

Sequence variability of rpoB in Streptococcus spp. and related genera.

Interspecies rpoB gene sequence variability was analyzed by using the in-house program sequence variability analysis program (SVARAP), which uses the Excel program to simultaneously process sets of up to 100 sequences of <4,000 nucleotides and allows comparison of data from two sets of sequences. Successive site-by-site analysis and successive window analysis of 60 nucleotide sites were used to reveal regions with particular patterns of variability. We tabulated site variability as the proportion of sequences that differ from the consensus sequence at a given site. Variability was calculated as follows: 100 − (maximum value of frequency for each of the four nucleotides at a given position). Our program requires nucleotide sequence alignment format as input and produces a numerical and graphical portrayal of variability as output. This program was applied to a file of eight rpoB complete sequences including the three complete sequences determined in the present study (S. anginosus, S. equinus, and A. defectiva) and sequences published in GenBank for S. pneumoniae (AE008542 and AE007486), S. agalactiae (AL766844 and AE014199), and S. pyogenes (AE006480). After sequence alignment with CLUSTAL X, v.1.8. Aligned sequences were copied, pasted into our program, and then automatically processed. Each nucleotide for each sequence was automatically assigned to a different cell in order to align nucleotides at a given position in the same column. The program then calculated the consensus nucleotide (defined as the most frequent nucleotide at a each site in the set of sequences), the absolute numbers of each of four nucleotides (G, A, C, and T), deletions, or insertions and their frequency (as a percentage). All of these data were processed for a window of 60 nucleotides to calculate the median, as well as the mean highest and lowest variabilities with the standard deviations, and the results were plotted within graphical windows. The program permitted the determination of a 740-bp variable region surrounded by two consensus regions, and this variable region was further tested for the constitution of an rpoB-streptococcus database.

TABLE 4.

Percentage of partial rpoB gene sequence similarity in 33 Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Gemella, Abiotrophia, and Granulicatella spp.

| Species | % rpoB gene sequence similaritya with:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. gallolyticus | S. macedonicus | S. pasteurianus | S. anginosus | S. intermedius | S. constellatus | S. lutetientis | S. bovis | S. equinus | S. salivarius | S. oralis | S. pneumoniae | S. dysgalactiae | S. pyogenes | G. morbillorum | G. haemolysans | S. infantarius | S. mitis | S. acidominimus | S. suis | S. sanguinis | S. mutans | S. agalactiae | S. equi | S. difficile | E. faecalis | E. avium | E. sacharolyticus | E. gallinarum | E. casselli | E. faecium | G. adjacens | A. defectiva | |

| S. gallolyticus | 100.0 | 95.4 | 92.8 | 73.5 | 72.7 | 73.0 | 85.2 | 79.2 | 78.9 | 76.6 | 73.5 | 73.6 | 74.3 | 75.3 | 74.0 | 73.8 | 88.9 | 74.1 | 70.9 | 71.4 | 71.4 | 70.7 | 72.5 | 71.3 | 63.5 | 77.6 | 59.6 | 71.4 | 73.4 | 75.3 | 77.9 | 76.0 | 71.7 |

| S. macedonicus | 100.0 | 96.0 | 76.3 | 75.5 | 75.9 | 88.5 | 82.3 | 82.3 | 79.7 | 76.3 | 76.8 | 77.5 | 78.5 | 71.0 | 70.7 | 90.7 | 76.9 | 74.0 | 74.5 | 74.6 | 73.2 | 75.6 | 73.9 | 66.1 | 74.6 | 62.2 | 75.0 | 75.0 | 73.0 | 74.4 | 73.2 | 71.4 | |

| S. pasteurianus | 100.0 | 75.5 | 74.6 | 74.9 | 88.8 | 81.5 | 81.2 | 78.4 | 75.5 | 75.7 | 16.1 | 77.0 | 69.2 | 69.0 | 88.7 | 75.9 | 72.0 | 73.2 | 73.0 | 72.7 | 74.8 | 72.7 | 64.6 | 72.5 | 62.8 | 72.3 | 72.7 | 70.8 | 72.9 | 70.9 | 69.7 | ||

| S. anginosus | 100.0 | 93.3 | 92.0 | 79.1 | 66.1 | 85.9 | 86.2 | 83.4 | 83.3 | 85.4 | 85.2 | 62.7 | 62.8 | 75.2 | 83.8 | 82.8 | 83.6 | 82.1 | 83.0 | 84.6 | 83.0 | 75.9 | 66.0 | 69.7 | 63.4 | 67.6 | 63.7 | 63.8 | 63.0 | 63.3 | |||

| S. intermedius | 100.0 | 91.5 | 78.5 | 85.4 | 85.2 | 86.7 | 83.4 | 83.9 | 84.3 | 84.6 | 60.9 | 61.0 | 74.9 | 83.0 | 82.1 | 83.1 | 81.0 | 82.6 | 84.3 | 82.5 | 76.1 | 66.0 | 69.8 | 63.1 | 67.5 | 63.8 | 64.8 | 63.1 | 61.6 | ||||

| S. constellatus | 100.0 | 77.8 | 84.8 | 84.6 | 86.1 | 84.6 | 83.8 | 84.1 | 84.1 | 61.3 | 61.4 | 74.2 | 84.4 | 81.8 | 84.4 | 83.4 | 81.1 | 83.0 | 82.5 | 73.9 | 64.8 | 69.3 | 62.6 | 66.0 | 62.0 | 64.2 | 63.6 | 60.8 | |||||

| S. lutetientis | 100.0 | 90.3 | 89.4 | 83.8 | 81.0 | 81.0 | 80.9 | 81.2 | 69.1 | 69.0 | 93.5 | 80.4 | 77.2 | 78.9 | 76.8 | 77.4 | 79.7 | 76.8 | 70.0 | 72.0 | 66.8 | 71.4 | 72.8 | 69.3 | 70.4 | 70.0 | 66.9 | ||||||

| S. bovis | 100.0 | 98.7 | 91.6 | 88.4 | 88.5 | 89.0 | 89.2 | 64.4 | 64.5 | 85.9 | 88.2 | 84.1 | 85.9 | 83.6 | 84.3 | 87.9 | 84.3 | 76.9 | 67.8 | 71.1 | 66.3 | 67.5 | 64.5 | 65.6 | 65.6 | 62.7 | |||||||

| S. equinus | 100.0 | 90.3 | 87.2 | 88.0 | 88.0 | 87.9 | 64.5 | 64.6 | 85.1 | 87.2 | 84.6 | 85.7 | 84.1 | 84.3 | 87.5 | 83.9 | 77.0 | 67.7 | 70.7 | 66.2 | 67.5 | 64.6 | 65.2 | 65.8 | 62.3 | ||||||||

| S. salivarius | 100.0 | 89.5 | 89.0 | 89.2 | 89.5 | 63.7 | 63.8 | 79.8 | 88.4 | 86.4 | 88.4 | 86.2 | 83.9 | 87.9 | 86.2 | 75.6 | 67.0 | 70.0 | 64.9 | 66.9 | 63.4 | 65.1 | 65.2 | 62.8 | |||||||||

| S. oralis | 100.0 | 93.6 | 86.7 | 86.4 | 63.0 | 63.1 | 77.2 | 93.6 | 84.8 | 87.2 | 88.0 | 84.1 | 85.2 | 83.1 | 76.4 | 65.7 | 69.2 | 63.0 | 65.5 | 64.1 | 64.2 | 63.6 | 61.1 | ||||||||||

| S. pneumoniae | 100.0 | 85.6 | 85.6 | 63.8 | 63.9 | 77.2 | 94.4 | 84.9 | 87.4 | 86.6 | 83.4 | 85.4 | 82.6 | 77.0 | 66.0 | 70.7 | 63.2 | 65.5 | 64.6 | 64.5 | 63.6 | 61.1 | |||||||||||

| S. dysgalactiae | 100.0 | 96.4 | 62.9 | 62.9 | 77.0 | 85.2 | 85.1 | 86.4 | 84.4 | 85.2 | 86.9 | 86.7 | 75.9 | 66.6 | 71.1 | 64.4 | 66.6 | 63.7 | 63.8 | 63.8 | 61.1 | ||||||||||||

| S. pyogenes | 100.0 | 62.9 | 62.9 | 77.3 | 84.8 | 84.4 | 85.4 | 83.8 | 84.8 | 86.2 | 86.4 | 75.7 | 67.1 | 70.7 | 64.2 | 67.1 | 63.5 | 63.5 | 63.3 | 61.9 | |||||||||||||

| G. morbillorum | 100.0 | 99.4 | 71.1 | 63.1 | 62.6 | 62.4 | 60.9 | 61.8 | 63.7 | 60.9 | 63.4 | 75.8 | 58.9 | 75.5 | 71.8 | 74.8 | 75.7 | 75.8 | 72.7 | ||||||||||||||

| G. haemolysans | 100.0 | 71.1 | 63.2 | 62.7 | 62.5 | 61.0 | 61.8 | 63.8 | 61.0 | 63.5 | 75.9 | 59.0 | 75.6 | 71.8 | 74.7 | 75.5 | 75.5 | 72.4 | |||||||||||||||

| S. infantarius | 100.0 | 76.6 | 74.2 | 75.5 | 73.5 | 73.0 | 76.2 | 73.5 | 67.0 | 74.9 | 63.1 | 74.2 | 75.3 | 72.8 | 74.0 | 73.3 | 70.1 | ||||||||||||||||

| S. mitis | 100.0 | 84.1 | 85.6 | 85.4 | 83.1 | 84.4 | 81.5 | 76.4 | 65.9 | 68.7 | 62.8 | 65.8 | 64.1 | 64.4 | 65.0 | 62.4 | |||||||||||||||||

| S. acidominimus | 100.0 | 90.2 | 84.8 | 84.4 | 84.1 | 85.4 | 75.4 | 64.5 | 68.4 | 63.4 | 65.8 | 63.3 | 63.0 | 63.6 | 61.5 | ||||||||||||||||||

| S. suis | 100.0 | 86.4 | 85.1 | 85.7 | 83.1 | 75.9 | 66.4 | 70.3 | 64.4 | 65.6 | 63.7 | 65.1 | 64.7 | 62.3 | |||||||||||||||||||

| S. sanguinis | 100.0 | 81.6 | 82.0 | 83.8 | 74.8 | 63.7 | 67.9 | 62.7 | 65.0 | 62.7 | 63.5 | 61.8 | 61.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| S. mutans | 100.0 | 85.9 | 85.9 | 74.9 | 64.9 | 69.3 | 63.2 | 65.9 | 62.9 | 64.4 | 63.7 | 61.5 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| S. agalactiae | 100.0 | 85.7 | 76.4 | 66.4 | 71.3 | 64.8 | 67.2 | 64.1 | 64.9 | 64.8 | 63.3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| S. equi | 100.0 | 74.1 | 64.0 | 68.4 | 63.2 | 65.3 | 62.2 | 63.4 | 62.6 | 60.9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| S. difficile | 100.0 | 71.7 | 76.2 | 70.6 | 79.1 | 83.9 | 71.1 | 68.0 | 65.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E. faecalis | 100.0 | 66.7 | 84.3 | 80.2 | 83.8 | 84.2 | 81.9 | 75.3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E. avium | 100.0 | 67.1 | 69.4 | 64.4 | 65.2 | 63.7 | 61.1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E. sacharolyticus | 100.0 | 79.6 | 83.4 | 85.8 | 81.1 | 77.5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E. gallinarum | 100.0 | 86.1 | 80.6 | 76.6 | 74.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E. casselli | 100.0 | 85.3 | 79.1 | 77.6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E. faecium | 100.0 | 79.6 | 77.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| G. adjacens | 100.0 | 76.0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A. defectiva | 100.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Full genus and species names can be found in Table 2.

Streptococcus and related genus partial rpoB sequence database.

Partial reverse and forward (bidirectional) sequencing of a 740-bp fragment was obtained by using internal primers at positions 2333 (Strepto F [5′-AARYTIGGMCCTGAAGAAAT-3′]) and 3073 (Strepto R [5′-TGIARTTTRTCATCAACCATGTG-3′]). Sequencing reactions were carried out with the reagents of the ABI Prism dRhodamine dye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions and with the following program: 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 10 s, primer annealing at 50°C for 10 s, and extension at 60°C for 2 min. Products of sequencing reactions were separated by electrophoresis on a 0.2-mm 6% polyacrylamide denaturing gel and recorded with an ABI Prism 377 DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems) according to the standard protocol of the supplier. This protocol was applied to the collection of 33 Streptococcus and related genus species listed in Table 1 in order to set up a reference partial rpoB gene database.

Molecular signatures in closely related Streptococcus species.

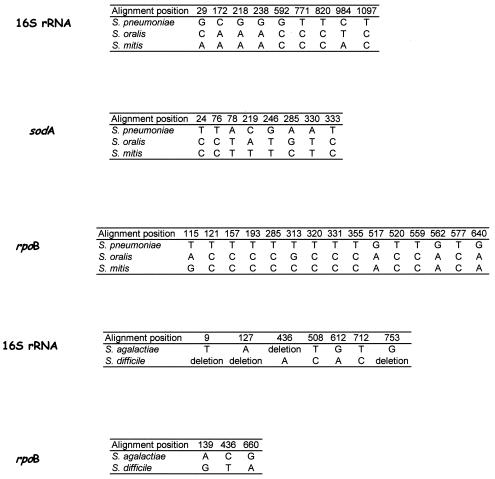

Partial rpoB sequences of closely related species exhibiting ambiguous phenotypic and molecular identifications were aligned for the search of positions that distinguished related species (molecular signatures) (Fig. 1). For that purpose, we aligned rpoB partial sequences determined in 10 S. pneumoniae isolates (including two sequences from GenBank, accession numbers AE008542 and AE007486) with that of S. mitis and S. oralis. Based on these signatures, we designed the primer pair rpoBpneumoF (3′-TGTTAACATGTTGGTTCGTGTT-5′) and rpoBpneumoR (3′-CATCAAAGACTGGTGTCGCA-5′) for the specific amplification and sequencing of S. pneumoniae rpoB. These primers were included in a PCR (under the conditions described above except for a hybridization temperature of 56°C) incorporating ten S. pneumoniae isolates, five S. mitis isolates, and five S. oralis isolates. Likewise, we aligned rpoB sequences determined in ten S. agalactiae isolates (including two sequences from GenBank, accession numbers AL766844 and AE014199) with S. difficile. Combinations of base positions unique to S. pneumoniae and S. agalactiae were defined as molecular signatures for these species.

FIG. 1.

Molecular signatures observed in the 16S rRNA, sodA, and rpoB genes in the S. pneumoniae complex and in the S. agalactiae-S. difficile group.

rpoB sequence-based identification blind testing.

The rpoB-based system we developed to identify streptococci was applied to a collection of 162 clinical isolates in order to assess its specificity (Table 2). This collection included 102 isolates of streptococci and 60 isolates belonging to other bacterial genera, including species responsible for endocarditis. After the isolates were coded, extraction of bacterial DNA and PCRs incorporating primer pair Strepto F-Strepto R were performed as described above. The presence of 740-bp amplicons was revealed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and amplicons were sequenced by using the sequencing primers described above. Sequences were aligned by using FASTA with the streptococcus rpoB database in Infobiogen (http://www.infobiogen.fr/services/analyseq/cgi-bin/fasta_in.pl), and identification was assessed by >97% similarity with one of the database sequence.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers of the streptococcal rpoB sequences determined in the present study are AF535167 for the S. mutans complete rpoB sequence, AF535187 for the S. equinus complete rpoB sequence, AF535183 for the S. anginosus complete rpoB sequence, AF535173 for the A. defectiva complete rpoB sequence, AF535168 for the S. oralis partial rpoB sequence, AF535169 for the S. salivarius partial rpoB sequence, AF535170 for the S. sanguinis partial rpoB sequence, AF535171 for the S. suis partial rpoB sequence, AF535181 for the S. acidominimus partial rpoB sequence, AF535182 for the S. agalactiae partial rpoB sequence, AF535184 for the S. constellatus partial rpoB sequence, AF535191 for the S. difficilis partial rpoB sequence, AY315158 for the S. lutetiensis partial rpoB sequence, AY315157 for the S. pasteurianus partial rpoB sequence, AY315156 for the S. macedonicus partial rpoB sequence, AY315154 for the S. gallolyticus partial rpoB sequence, AY315155 for the S. infantarius partial rpoB sequence, AF535185 for the S. dysgalactiae partial rpoB sequence, AF535186 for the S. equi partial rpoB sequence, AF535190 for the S. intermedius partial rpoB sequence, AF535188 for the S. mitis partial rpoB sequence, AF535189 for the S. bovis partial rpoB sequence, AF535192 for the E. avium partial rpoB sequence, AF535174 for the E. casselliflavus partial rpoB sequence, AF535178 for the E. faecalis partial rpoB sequence, AF535176 for the E. faecium partial rpoB sequence, AF535177 for the E. gallinarum partial rpoB sequence, AF535175 for the E. saccharolyticus partial rpoB sequence, AF535179 for the G. haemolysans partial rpoB sequence, AF535180 for the G. morbillorum partial rpoB sequence, and AF535172 for the G. adjacens partial rpoB sequence.

RESULTS

Determination of rpoB sequences in Streptococcus and related genus species and construction of a partial rpoB sequence database.

Consensus primers 31F and 830R permitted the amplification of an 800-bp rpoB fragment in S. anginosus, S. equinus, and A. defectiva, and additional consensus primers pairs allowed us to determine the almost the entire rpoB sequence in these three species: primers 1252F, 2057F, and 2215F combined with primers 116R and 503R allowed us to further sequence the 3′ extremity of the gene in the three species, whereas combining primer 7487F with 585R, 371R, and 730R allowed us to further sequence the 5′ extremity. Both 3′ and 5′ extremities were obtained by using the genome walker kit incorporating primer GW520R and primer GW2881F, respectively. Overall, a complete 3,567-bp sequence was determined from the ATG start codon to the TGA stop codon in S. anginosus, a 3,573-bp sequence was determined in S. equinus, and a 3,651-bp sequence was determined in A. defectiva. After incorporation of these three complete sequences with those available in GenBank for S. agalactiae, S. pyogenes (two sequences in GenBank), S. pneumoniae, and S. mutans in the SVARAP software, four variable regions, characterized by lengths of 450 to 750 bp and by a mean variabilitiy of >5%, flanked by conserved regions (mean variability, <5%), were identified in streptococcus rpoB genes (numbered on the basis of the S. pyogenes rpoB gene sequence, GenBank accession number AE006480): region I extended from positions 1050 to 1800 measured 750-bp in length and exhibited a 2.2 to 8.4% variability; region II extended from positions 1800 to 2250, measured 450 bp, and exhibited a 2.5 to 12.7% variability; region III extended from positions 2250 to 2750, measured 500 bp, and exhibited a 2.5 to 13.6% variability; and region IV extended from positions 2750 to 3500 (750-bp length; 2.7 to 8.8%) (Table 4). We selected region IV as a suitable target for identification of clinical isolates. Consensus PCR primers Strepto 3F and Strepto 3R were designed for amplification of the region, and an rpoB partial sequence database analysis was done for an additional 30 Streptococcus and related genus species under investigation.

Determination of molecular signatures in Streptococcus and related genera species.

As for the S. pneumoniae, S. mitis, and S. oralis group, we found 15 signatures in S. pneumoniae at positions 115, 121, 157, 193, 285, 313, 320, 331, 355, 517, 520, 559, 562, 577, and 640 of the partial rpoB sequence (Fig. 1). These signatures were all specific for S. pneumoniae. As for the 16S rRNA gene, nine bases were unique to S. pneumoniae at positions 29, 172, 218, 238, 592, 711, 820, 984, and 1097 of the gene sequence. Eight bases were unique to S. pneumoniae in the sodA gene at positions 24, 76, 78, 219, 246, 285, 330, and 333 of the gene sequence. PCR incorporating primers rpoBpneumoF and rpoBpneumoR yielded an expected 154-bp band in 10 of 10 S. pneumoniae isolates. No amplicon was observed in five of five S. mitis isolates and nonspecific amplicons were obtained in two of five S. oralis isolates. As for the differentiation of S. agalactiae from S. difficile, three positions distinguished these two species in partial rpoB sequence: position 139 is an adenine in S. agalactiae and a guanine in S. difficile, position 438 is a cytosine in S. agalactiae and a thymidine in S. difficile, and position 660 is a guanine in S. agalactiae and an adenine in S. difficile. A total of seven positions distinguished these two species in the 16S rRNA gene sequence.

Results of blind identification testing.

A 740-bp amplicon was obtained in all of the 102 Streptococcus sp. isolates previously identified at the species level and belonging to different species of Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Abiotrophia, Gemella, and Granulicatella genera. Sequence analysis assigned every one of these isolates to the correct species. Use of the primer pair Strepto F-Strepto R yielded no amplification with the isolates belonging to species other than streptococci with the exception of two B. cereus isolates, which produced an amplicon of the expected size. Sequencing this amplicon yielded a sequence exhibiting complete identity with that of B. cereus rpoB in GenBank (accession number AF205342).

DISCUSSION

The data we present here show that PCR amplification of a 740-bp rpoB gene fragment by using the primer pair Strepto F-Strepto R, followed by sequence analysis, is a suitable molecular approach for the identification of Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Gemella, Abiotrophia, and Granulicatella isolates at the species level. Moreover, this primer pair was shown to be almost specific for this group of microorganisms, since no amplification products were obtained from 58 other bacterial isolates belonging to nonstreptococcal species, including other gram-positive cocci and species responsible for infectious endocarditis. One exception was B. cereus, which was amplified but unambiguously identified by its sequence (39). To date, the primary method for the molecular identification of Streptococcus and related genera species has been the analysis of genomic DNA restriction fragment length patterns on Southern blots probed with labeled rRNA genes (10, 18). PCR and sequencing of rRNA genes, however, have been found to have limited discriminating power for these species, since the 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity has been shown to be >99% for S. pneumoniae, S. mitis, and S. oralis (22). Also, some isolates phenotypically and genetically most closely related to S. mitis were found to harbor genes encoding the virulence determinants pneumolysin and autolysin classically associated with S. pneumoniae (51). In contrast, the sequence similarity of the groESL genes was 91.6 to 95.1% in this group of species (49) and 92 to 96% for sodA gene (23, 35). Partial sequence analysis of the sodA gene was shown to discriminate S. pneumoniae among the mitis group of streptococci (23). As for the partial rpoB gene sequences determined in our study, the similarity was in the same order of magnitude of 94%. The rpoB gene, then, clearly has a reasonable discriminative power for this group of Streptococcus species. Moreover, we determined 15 signature positions in the 740-bp sequence, which discriminated each one of these three species and served as a basis for the design of species-specific molecular probes. Partial rpoB sequence-based diagnosis with the primers we developed here could be a suitable alternative for the molecular diagnosis of streptococcal endocarditis. Morever, the rpoB-based system we developed was able to accurately identify Enterococcus, Gemella, Abiotrophia, and Granulicatella, four genera comprising well-known and emerging species also responsible for infective endocarditis (7, 52). In Enterococcus species also, 16S rRNA gene sequence did not reliabily distinguish isolates at the species level, and groESL gene-derived PCR primers developed for Streptococcus species did not amplify Enterococcus species (49).

The primer pairs developed here for the detection and identification of streptococci complement those previously designed for rpoB gene-based diagnosis of Staphylococcus species (12). Altogether, 80% of infective endocarditis cases can be diagnosed by partial rpoB gene amplification and sequencing.

Likewise, S. agalactiae and S. difficile are indistinguishable by their phenotypic characters, including the protein profile (50), and share 97.7% similarity in their 16S-23S rRNA spacer, a high value for streptococci (6). S. difficile was not included in a previous study of partial sodA gene sequence for the identification of Streptococcus species (35). Although these organisms share an almost identical partial rpoB gene sequence, they do exhibit three distinct mutations in the rpoB sequence that could serve as a molecular signature for their accurate identification. In addition to S. pneumoniae (8), S. agalactiae is a leading cause of bacterial meningitis, particularly in neonates, a condition requiring rapid and accurate etiological diagnosis. With respect to this goal, rpoB exhibited >15% sequence divergence, a value leading to unambiguous species identification.

Apart from the 16S rRNA gene-based methods, molecular tools developed thus far for the identification of Streptococcus and related genera did not target these five genera at once as we did in the present study. Indeed, groESL gene-based techniques were restricted to the genus Streptococcus (49) and two different systems based on sequence of the sodA gene have been developped for the genera Streptococcus (35) and Enterococcus (36). Likewise, PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the entire 16S-23S rRNA region (45) included 178 strains belonging to 30 species and subspecies of the genus Streptococcus and further studies based on the analysis of the 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer included some species belonging to the same Streptococcus group, such as the S. mitis group (2), S. agalactiae group (6, 15), and the S. thermophilus group (32). The rpoB gene-based primer pair determined in the present study may be helpful for the accurate detection and identification of Streptococcus species and related genera of medical interest.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge expert review of the manuscript by Patrick Kelly.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ayoub, E. M., and P. Ferrieri. 1994. Group A streptococcal diseases, p. 349-366. In P. D. Hoeprich, M. C. Jordan, and A. R. Ronald (ed.), Infectious diseases, 5th ed. J. B. Lippincott Co., Philadelphia, Pa.

- 2.Barsotti, O., D. Décoret, and F. N. R. Renaud. 2002. Identification of Streptococcus mitis group species by RFLP of the PCR-amplified 16S-23S rDNA intergenic spacer. Res. Microbiol. 153:687-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beighton, D., J. M. Hardie, and R. A. Whiley. 1991. A scheme for the identification of viridans streptococci. J. Med. Microbiol. 35:367-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bentley, R. W., J. A. Leigh, and M. D. Collins. 1991. Intrageneric structure of Streptococcus based on comparative analysis of small-subunit rRNA sequences. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 41:487-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergeron, M. G., D. Ke, C. Menard, F. J. Picard, M. Gagnon, M. Bernier, M. Ouellette, P. H. Roy, S. Marcoux, and W. D. Fraser. 2000. Rapid detection of group B streptococci in pregnant women at delivery. N. Engl. J. Med. 343:175-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berridje, B. R., H. Bercovier, and P. F. Frelier. 2001. Streptococcus agalactiae and Streptococcus difficile 16S-23S intergenic rDNA: genetic homogeneity and species-specific PCR. Vet. Microbiol. 78:165-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casalta, P. Y., G. Habib, B. Lascola, M. Drancourt, T. Caus, and D. Raoult. 2002. Molecular diagnosis of Granulicatella elegans on the cardiac valve of a patient with culture-negative endocarditis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1845-1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaves, F., C. Campelo, F. Sanz, and J. R. Otero. 2003. Meningitis due to mixed infection with penicillin-resistant and penicillin-susceptible strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:512-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins, M. D., and P. A. Lawson. 2000. The genus Abiotrophia (Kawamura et al.) is not monophyletic: proposal of Granulicatella gen. nov., Granulicatella adjacens comb. nov., Granulicatella elegans comb. nov., and Granulicatella balaenopterae comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. E vol. Microbiol. 50:365-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daly, J. A., N. L. Clifton, K. C. Seskin, and W. N. Gooch. 1991. Use of rapid, nonradioactive DNA probes in culture confirmation tests to detect Streptococcus agalactiae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Enterococcus spp. from pediatric patients with significant infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:80-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denys, G. A., and R. B. Carrey. 1992. Identification of Streptococcus pneumoniae with a DNA probe. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:2725-2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drancourt, M., and D. Raoult. 2002. rpoB gene sequence-based identification of Staphylococcus species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1333-1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drancourt, M., and D. Raoult. 1999. Characterization of mutations in the rpoB gene in naturally rifampin-resistance Rickettsia species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2400-2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flynn, C. E., and K. L. Ruoff. 1995. Identification of Streptococcus milleri group isolates to the species level with a commercially available rapid test. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2704-2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forsman, P., A. Tilsala-Timisjarui, and T. Alatossava. 1997. Identification of staphylococcal and streptococcal causes of bovine mastitis using 16S-23S rRNA spacer regions. Microbiology 143:3491-3500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geslin, P., A. Fremaux, C. Spicq, G. Sissia, and S. Georges. 1997. Use of a DNA probe test for identification of Streptococcus pneumoniae nontypable strains. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 418:383-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gingeras, T. R., G. Glandour, F. Wang, A. Berno, P. M. Small, F. Drobniewski, D. Alland, E. Desmond, M. Hlondniy, and J. Drenkow. 1998. Simultaneous genotyping and species identification using hybridization pattern recognition analysis of generic Mycobacterium DNA arrays. Genome Res. 8:435-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heelan, J. S., S. Wilbur, G. Depetris, and C. Letourneau. 1996. Rapid antigen testing for group A streptococcus by DNA probe. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 24:65-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hillman, J. D., S. W. Andrews, S. Palner, and P. Strashenko. 1989. Adaptative changes in a strain of Streptococcus mutans during colonization of the human oral cavity. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2:231-239. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaijalainen, T., S. Rintamaki, E. Herva, and M. Leinonen. 2002. Evaluation of gene-technological and conventional methods in the identification of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Microbiol. Methods 51:111-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawamura, Y., X. Hou, F. Sultana, S. Liu, H. Yamamoto, and T. Ezaki. 1995. Transfer of Streptococcus adjacens and Streptococcus defectivus to Abiotrophia gen. nov. as Abiotrophia adjacens comb. nov. and Abiotrophia defectiva comb. nov., respectively. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:798-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawamura, Y., X. Hou, F. Sultana, H. Miura, and T. Ezaki. 1995. Determination of 16S rRNA sequences of Streptococcus uveitis and Streptococcus gordonii and phylogenetic relationships among members of the genes Streptococcus. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:406-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawamura, Y., R. A. Whiley, S. E. Shu, T. Ezaki, and J. M. Hardie. 1999. Genetic approaches to the identification of mitis group within the genus Streptococcus. Microbiology 145:2605-2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kilian, M., L. Mikkelsen, and J. Henrichsen. 1989. Taxonomic studies of viridans streptococci: description of Streptococcus gordonii sp. nov. and emended descriptions of Streptococcus sanguis (White and Niven 1946). Streptococcus oralis (Bridge and Sneath 1982), and Streptococcus mitis (Andrews and Hurder 1906). Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 39:471-484. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim, B. J., K. H. Lee, B. N. Parks, S. J. Kim, G. H. Bai, and Y. H. Kook. 2001. Differentiation of mycobacterial species by PCR-restriction analysis of DNA (342 base pairs) of the RNA polymerase gene (rpoB). J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2102-2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ko, K. S., H. K. Lee, M. Y. Park, H. K. Lee, Y. J. Yun, S. Y. Woo, H. Miyamoto, and Y. H. Kook. 2002. Application of RNA polymerase β-subunit gene (rpoB) sequences for the molecular differentiation of Legionella species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2653-2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koedel, U., W. M. Scheld, and H. W. Pfister. 2002. Pathogenesis and physiopathology of pneumococcal meningitis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2:721-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee, H. K., B. J. Kim, J. H. Kim, K. H. Park, S. J. Kim, and Y. H. Kook. 2000. Differentiation of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu leto on the basis of RNA polymerase gene (rpoB) sequences. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2557-2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mawn, J. A., A. J. Simpson, and S. R. Heard. 1993. Detection of the C protein gene among group B streptococci using PCR. J. Clin. Pathol. 46:633-636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mollet, C., M. Drancourt, and D. Raoult. 1997. rpoB sequence analysis as a novel basis for bacterial identification. Mol. Microbiol. 26:1005-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore, M. R., S. J. Schrag, and A. Schuchat. 2003. Effects of intrapartum antimicrobial prophylaxis for prevention of group B-streptococcal disease on the incidence and ecology of early-onset neonatal sepsis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3:201-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mora, D., G. Ricci, S. Guglielmetti, D. Daffonchio, and M. G. Fortina. 2003. 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer region sequence variation in Streptococcus thermophilus and related dairy streptococci and development of a multiplex ITS-SSCP analysis for their identification. Microbiology 149:807-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morrison, K., D. Lake, J. Crook, G. Carlone, E. Ades, R. Facklam, and J. Sampson. 2000. Confirmation of psaA in all 90 serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae by PCR and potential of this assay for identification and diagnosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:434-437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poyart, C., G. Quesne, S. Coulon, P. Berche, and P. Trieu-Cuot. 1998. Identification of streptococci to species level by sequencing the gene encoding the manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:41-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poyart, C., G. Quesne, and P. Trieu-Cuot. 2000. Sequencing the gene encoding manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase for rapid species identification of enterococci J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:415-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poyart, C., G. Quesne, and P. Trieu-Cuot. 2002. Taxonomic dissection of Streptococcus bovis group by analysis of manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase gene (sodA) sequences: reclassification of “Streptococcus infantarius subsp. coli” as Streptococcus lutetiensis sp. nov., and of Streptococcus bovis biotype 11.2 as Streptococcus pasteurianus sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. E vol. Microbiol. 58:1247-1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poyart, C., T. Lambert, P. Morand, P. Abassade, G. Quesne, Y. Baudouy, and P. Trieu-Cuot. 2002. Native value endocarditis due to Enterococcus hirae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2689-2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qi, Y., G. Patra, X. Liang, L. E. Williams, S. Rose, R. J. Redkar, and V. G. Del Vecchio. 2001. Utilization of the rpoB gene as a specific chromosomal marker for real-time PCR detection of Bacillus anthracis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3720-3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Renesto, P., J. Gouvernet, M. Drancourt, V. Roux, and D. Raoult. 2000. Use of rpoB gene analysis for detection and identification of Bartonella species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:430-437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Renesto, P., K. Lorvellec-Gullion, M. Drancourt, and D. Raoult. 2000. rpoB gene analysis as a novel strategy for identification of spirochetes from the genera Borrelia, Treponema, and Leptospira. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2200-2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruoff, K. L., R. A. Whiley, and D. Beighton. 1999. Streptococcus, p. 283-296. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, M. A. Pfaller, F. C. Tenover, and R. H. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 7th ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 42.Salo, P., A. Ortquist, and M. Leinonen. 1995. Diagnosis of bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia by amplification of pneumolysin gene fragment in serum. J. Infect. Dis. 171:479-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schlegel, L., F. Grimont, E. Ageron, P. A. D. Grimont, and A. Bouvet. 2003. Reappraisal of the taxonomy of the Streptococcus bovis/Streptococcus equinus complex and related species: description of Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus subsp. nov., S. gallolyticus subsp. macedonicus subsp. nov., and S. gallolyticus subsp. pasteurianus subsp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:631-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schleifer, K. H., and R. Kilpper-Balz. 1987. Molecular and chemotaxonomic approaches to the classification of streptococci, enterococci, and lactococci: a review. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 10:1-19. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stein, A., and D. Raoult. 1992. A simple method for amplification of DNA from paraffin-embedded tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:5237-5238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taillardat-Bisch, A. V., M. Drancourt, and D. Raoult. 2003. RNA polymerase beta-subunit-based phylogeny of Ehrlichia spp., Anaplasma spp., Noerickettsia spp., and Wolbachia pipientis. Int. J. Syst. E vol. Microbiol. 53:455-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tardif, G., M. C. Sulavik, G. W. Jones, and D. B. Clewell. 1989. Spontaneous switching of the sucrose-promoted colony phenotype in Streptococcus sanguis. Infect. Immun. 57:3945-3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Teng, L. J., P. R. Hsueh, J. C. Tsai, P. W. Chen, J. C. Hsu, H. C. Lai, C. N. Lee, and S. W. Ho. 2002. GroESL sequence determination, phylogenetic analysis, and species differentiation for viridans group streptococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3172-3178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vandamme, P., L. A. Devriese, B. Pot, K. Kersters, and P. Melin. 1997. Streptococcus difficile is a non-hemolytic group B, type Ib Streptococcus. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:81-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whatmore, A. M., A. Efstratiou, A. P. Pickerill, K. Broughron, G. Woodard, D. Sturgeon, R. George, and C. G. Dowson. 2000. Genetic relationships between clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus oralis, and Streptococcus mitis: characterization of “atypical” pneumococci and organisms allied to S. mitis harboring S. pneumoniae virulence factor-encoding genes. Infect. Immun. 68:1374-1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Woo, P. C. Y., D. M. W. Tam, K. W. Leung, S. K. P. Lau, J. L. L. Teng, M. K. M. Wong, and K. Y. Yuen. 2002. Streptococcus sinensis sp. nov., a novel species isolated from a patient with infective endocarditis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:805-810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]