Abstract

Background:

Patterned electrical neuromuscular stimulation (PENS) uses the electrical stimulation of sensory and motor nerves to achieve a skeletal muscle contraction using an electromyogram-derived functional pattern. PENS is used extensively for neuromuscular reeducation and treatment of muscle disuse atrophy.

Purpose:

To explore the effectiveness of PENS as applied to the quadriceps muscles on the vertical jump of an athletic population.

Study Design:

Experimental with control and repeated measures over time.

Methods:

Healthy college athletes (54 women, 75 men) were divided into 3 groups (control, n = 30; jump, n = 33; and jump with PENS, n = 63). There was no difference among groups’ height and weight. Athletes performed a baseline standing vertical jump using a vertical jump system. The control group continued its normal daily activities with no jumping tasks included. The jump groups performed 3 sets of 12 repetitions with a 2-minute rest between sets at a frequency of 3 times per week. The PENS group did the jumping with the coordination of an electrical stimulation system. Vertical jump was retested after 6 weeks of intervention and 2 weeks after cessation.

Results:

A 3-way repeated measures analysis of variance for time (control, jump alone, jump with PENS) revealed a significant difference (P < 0.05) for time and an interaction between time and treatment, as well as a significant difference for the PENS group from baseline to posttest and for the jump group from posttest to follow-up jump. There was no significant difference between groups for the baseline vertical jump.

Conclusions:

This study demonstrated that 6 weeks of vertical jump training coordinated with PENS resulted in a greater increase than jumping only or control. This pattern of stimulation with PENS in combination with jump training may positively affect jumping.

Keywords: electrical stimulation, patterned stimulation, jumping, muscle reeducation

Over the past decade, a new form of stimulation has emerged: patterned electrical neuromuscular stimulation (PENS). PENS is a form of electrical stimulation based on electromyographic patterns of healthy individuals during functional movement or activity (FX Palermo, personal communication; surface electromyographic patterns were obtained for vertical jumps performed on healthy college football players and minor league hockey players—the patterns were averaged and evaluated for spectral components as well as timing). PENS replicates the typical firing patterns of muscles (ie, agonist and antagonist muscle pairs or reciprocal muscle pairs) in triphasic9 patterns (ballistic), biphasic patterns (reciprocal), or functional patterns. This approach to neuromuscular reeducation attempts to provide precisely timed sensory input that duplicates the firing activity of sensory and motor neurons and muscle stretch receptors during voluntary activity. There is an increasing body of evidence suggesting that functional patterns of electrical stimulation—which are task specific and in conjunction with voluntary movement—can improve motor learning and functional performance.15,35,42-44 Research has been performed over the past decade indicating that electrical stimulation can enhance correction of foot drop,24 walking speed,25 and balance22,41 in individuals with hemiparesis.

Early studies on enhancement of muscle strength using electrical currents focused on high-intensity, generally uncomfortable isometric contractions with medium frequency alternating currents (MFACs) at maximum voluntary contraction levels to enhance muscle strength, as opposed to functional performance. Russian stimulation, developed by Dr Kotz,26,27 was presented at the 1976 Olympic Games in Montreal, Canada, as a strength performance enhancement in Russian powerlifters. Claims were made that the stimulation enhanced strength as much as 30%. Following the initial enthusiasm, clinical trials demonstrated that Russian stimulation (MFAC: 2500 Hz, burst modulated at 50 Hz with a 200-microsecond duration) has similar effects on voluntary isometric contractions in rehabilitation. Its ability to enhance performance in healthy athletic populations was unknown.26,27 PENS is low frequency (50 Hz) and has a short-phase duration (< 100 microseconds); it is an asymmetric biphasic waveform based on the electromyographic patterns of functional tasks.36-39 The PENS sensation is comfortable, whereas MFAC is often intense and uncomfortable.

PENS has been in use since 1992 in sports15,31,42 and rehabilitation applications.3,5-7,33,34,40,47 Currently, there are more than 5000 devices in use in the United States, with a focus in neuromuscular reeducation. It has been used in geriatric rehabilitation and with professional and collegiate athletic programs.36-39 The devices are used postinjury and for the reduction of muscle disuse atrophy following total knee and hip arthroplasty.45 Its impact on performance enhancement has not been tested in randomized controlled trials.12,13,17 PENS may have the potential to enhance functional performance in healthy nonathletic and athletic populations at comfortable levels of stimulation by altering neuromuscular recruitment and optimizing recruitment patterns.46

Purpose of the Study

Given the basic validation of electrical stimulation in the treatment of muscle disuse atrophy,14 the plan was to determine if electrical stimulation could improve function. The research question was, does brief electromyogram-patterned electrical stimulation to the quadriceps muscles enhance vertical jump in asymptomatic collegiate athletes? The independent variable was the electrical stimulation (intervention); the dependent variable was vertical jump (in centimeters).

Materials and Methods

Participants

Healthy college athletes (> 18 years of age) were recruited from a Division III institution via verbal contact with team coaches and a flyer posted in the athletic center. Exclusion criteria included systemic pathology and lower extremity injuries in the past year requiring medical consult. The athletes read and signed a consent form approved by the university institutional review board for the protection of human subjects. Overall, 129 healthy college athletes (women, n = 54; men, n = 75) were divided into 3 groups (control, n = 30; jump, n = 33; jump with PENS, n = 66). There was no difference among the groups in mean height (174.41 ± 9.66 cm) and weight (77.18 ± 14.88 kg). Although athletes were not in season during the research process for their sports (see Table 1), those involved in off-season conditioning were instructed to not change their activity levels for the duration of data collection.

Table 1.

Sports of the study groups.a

| Control | Jump Only | Jump + PENS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseball/softball | 6 | 3 | 15 |

| Basketball | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Equestrian | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Football | 3 | 9 | 13 |

| Gymnastics | 3 | 6 | 3 |

| Soccer | 9 | 9 | 0 |

| Track | 9 | 3 | 11 |

| Volleyball | 0 | 0 | 17 |

| Total | 30 | 33 | 66 |

Participants, n. PENS, patterned electrical neuromuscular stimulation.

Athletic schedules and accessibility were discussed to determine availability for group assignment (ie, control, jumping only, and jumping with patterned electrical neuromuscular stimulation [PENS]). If the athletes could consistently be available 3 times per week to complete the jump or PENS protocol, they were assigned to 1 of 3 groups. If the participant were willing to participate but could not commit to 3 sessions per week, he or she was assigned to the control group. At no time was the content of the group assignment discussed with the participant, nor was the participant allowed to select the activity. Thus, the protocol was not randomized, because the time commitment was a significant issue. Several athletes claimed to be available 3 times per week but failed to comply with the protocol and were thus dropped from the study (n = 8; 3 jump and 5 PENS volunteers).

Equipment

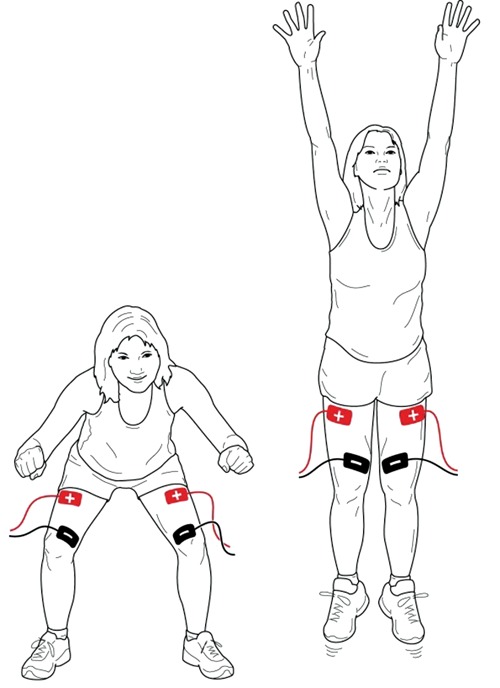

A Vertec® vertical jump system (Power Systems, Knoxville, Tennessee) was used to assess standing reach and vertical jump. An OmniStim FX2 Pro Electrical Stimulation system (Accelerated Care Plus, Reno, Nevada) was used to administer the electrical stimulation treatments. Two-by-four-inch (5 × 10 cm) rectangular electrodes (Accelerated Care Plus, Reno, Nevada) were placed transversely on the quadriceps muscles (Figure 1). Palpation of the quadriceps muscle during voluntary contraction was performed to ensure appropriate placement of the electrodes.

Figure 1.

Electrode placement and vertical jumping technique.

Procedures

Standing vertical reach was measured using the Vertec® system. Baseline data was obtained for vertical jump (pretest) via standard vertical jump protocol. The highest horizontal vane that could be displaced by the athlete’s hand was recorded. This procedure has been demonstrated to be reliable and valid.21,30 Each participant performed 3 jumps, and the mean value was used for statistical purposes.

The jumping group performed 3 sets of 12 jumps with no external stimulus applied. The PENS group performed 3 sets of 12 jumps with electrodes on the quadriceps muscles. The athletes received a standard auditory stimulus from the OmniStim FX2 unit 500 milliseconds before the initiation of electrical stimulation and synchronized a maximal voluntary muscle contraction with the electrical stimulation burst. Sufficient practice with submaximal muscle contractions was performed to confirm synchronization with the stimulus. The PENS parameters consisted of an asymmetrical biphasic square wave at a frequency of 50 Hz, a phase duration of 70 microseconds, and stimulus trains of 200 milliseconds. Before the jumps, stimulus intensity was gradually increased from a barely visible twitch to strong activation of the quadriceps muscles. The increase in the intensity was under the control of the athlete. At no time was a stimulus painful to the athlete (peak current, 50-140 mA). Both jumping groups rested for 2 minutes between sets and performed the jumping protocols 3 times per week for 6 weeks. The control group continued its normal activities with no additional jumping tasks incorporated into the daily routines.

At the conclusion of the 6-week period, vertical jump was reassessed for all athletes. Two weeks after the cessation of treatment, a follow-up vertical jump was reassessed for all athletes to determine if there were a carryover effect for the jumping or PENS intervention. The mean PENS intensity used by each athlete across all treatments was correlated with the change in vertical jump. This was performed to determine if a higher intensity stimulus resulted in a more substantial increase in vertical jump.

Data Analysis

The standing reach value was deducted from the maximum jump height for each condition to determine the vertical jump (in centimeters). The mean of the 3 jumps for each time and condition was used for analysis. Three-way analysis of variance and post hoc analysis were performed with SPSS 17.0. In addition, a correlation was completed between vertical jump height and the intensity of the electrical stimulation.

Results

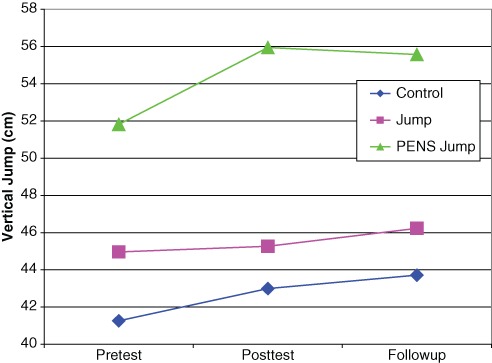

There was no significant difference among groups at the baseline vertical jump (P = 0.124) (Table 2). A 3-way repeated measures analysis of variance for time (control, jump only, jump with PENS) revealed a significant difference (P < 0.01) and an interaction between time and treatment (P < 0.01) (Figure 2). Post hoc analysis identified a significant difference for the jump group from the baseline to the follow-up jump (P = 0.04) and from posttest to the follow-up jump (P = 0.045). For the PENS group, there was a significant difference from baseline to posttest (P = 0.0001) and baseline to follow-up (P < 0.01).

Table 2.

Performance by treatment.

| Vertical Jump, cm | Change | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment: Time | Mean ± SE | Mean | Percentage | P |

| Control | ||||

| Pretest | 41.3 ± 16.8 | |||

| Posttest | 42.9 ± 17.1 | 1.6 | 4.7 | 0.155 |

| Follow-up | 43.7 ± 16.1 | 0.8 | 2.9 | 0.351 |

| Total change | 2.4 | 7.6 | 0.693 | |

| Jump | ||||

| Pretest | 44.9 ± 17.1 | |||

| Posttest | 45.3 ± 16.5 | 0.4 | 2.0 | 0.522 |

| Follow-up | 46.2 ± 16.3 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 0.045* |

| Total change | 1.3 | 4.8 | 0.040* | |

| PENSa | ||||

| Pretest | 51.8 ± 16.8 | |||

| Posttest | 55.9 ± 15.9 | 4.1 | 9.7 | 0.000* |

| Follow-up | 55.6 ± 15.8 | −0.3 | −0.6 | 0.209 |

| Total change | 3.8 | 8.9 | 0.000* | |

PENS, patterned electrical neuromuscular stimulation.

P < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Vertical jump by group across pretest, posttest, and follow-up.

Another way of examining the data is the percentage change from pretest to posttest. Although all groups demonstrated a mean increase, the PENS group was greater (9.7%) than both the jump only (2.0%) and the control (4.7%). An analysis of the change in vertical jump and the intensity of PENS did not reveal a significant correlation (overall, r = 0.052; men, r = −0.291; women, r = 0.513). Pillai trace and Wilks lambda calculation of observed power for this study was 1.000.

Discussion

Kotz27 documented the use of electrical stimulation for the treatment of muscle disuse atrophy, pain, and posttraumatic edema. Throughout the history of the search for enhanced muscle performance, electrical stimulation was considered an option in the development of enhanced muscle strength.19,23 Currier, Lehman, and Lightfoot10; Eriksson16; and Eriksson and Haggmark17 found no significant difference in isometric strength training regimens using maximum intensity electrical stimulation. Similarly, Halback and Straus20 and others2,4,11 found no difference in isokinetic strength development with electrical stimulation. Strength improved with electrical stimulation, but no advantage was found over training, and isometric strength gains from electrical stimulation did not carry over to dynamic tasks.4

Delitto et al12 reported strength gains with 4 weeks of electrical stimulation. Olympic judo athletes in Taiwan received normal training or electrical stimulation with MFAC according to the Kotz27 protocol (JC Castel, unpublished data, “Treatment of Elite Judo Athletes With Medium Frequency Currents Enhances Isokinetic Torque During High Speed Movement,” presented at the International Isokinetic and Electrical Stimulation Congress, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, 1992). The MFAC showed a significant improvement in strength (> 30%) under high-speed isokinetic testing (200° per second), suggesting a preferential training effect for type II fast-twitch fibers.7

Gains in type II high-speed power fibers generally take higher intensity exercise because of the recruitment sequence.7,32 Electrical stimulation can selectively recruit type II fibers because of their increased myelination of efferent nerves activating the motor units.7,32 The ability to increase strength may not directly translate into increased functional performance.32 Motor neuron recruitment and timing play an important role in functional task performance.32 PENS may be more efficient in timing and recruitment than high-intensity isometric contractions generated by MFAC.

This study demonstrated that 6 weeks of vertical jump training coordinated with PENS (asymmetric biphasic square waveform) resulted in a greater increase in jumping (4.1 cm) than that of jumping only (0.4 cm) and control (1.6 cm). PENS produces rhythmic, precisely timed muscle contractions.48 The 50-Hz frequency with a narrow-phase duration (70 microseconds) provides a comfortable stimulus that may enhance the release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum.48 This release of calcium may generate stronger muscle contractions during a PENS treatment.48 Because there was no correlation between intensity of the PENS stimulus and increased vertical jump, the strength of the stimulus may not be as important as the timing of the patterned stimulation. MacKay-Lyons29 described the importance of these specialized neural circuits as a collection of sensory and motor nerves and interneurons that influence movement patterns.

Muscle strength and power are determined by neural drive and muscle hypertrophy. Neuromuscular education strategies are designed to improve neural drive, motor timing, and neuromuscular activation at the myoneural junction. An early increase in strength is generally attributed more to neural adaptations than to muscle hypertrophy.32

The neuromuscular junction is critically important in determining the function of individual muscles during motor activation. Modulation of the efficacy of the neuromuscular junction greatly affects motor performance.28 The stimulation of motor neurons with the PENS waveform and burst pattern18 provides 2 important components in neuroeducation8: the activation of the nerve growth factor neurotrophin1,48 and the release of increased calcium at the neuromuscular junction.48 Calcium pooling, known as “the readily releasable pool,”48 also occurs during electrostimulation with PENS, thereby providing an immediate enhancement of motor recruitment lasting about 2 hours poststimulation.48

There are 2 shortcomings in this study. First, athletes were assigned to a treatment group according to their schedule and availability; thus, the treatment was not randomized. Second, the athletes’ sports were not controlled. However, a retrospective review of the data indicated an equitable distribution of jumping and nonjumping sports in each group. Overall, the PENS group had 25 of 66 athletes who participated in jumping sports such as basketball, volleyball, and gymnastics, whereas the jump group had 9 of 33 and the control group, 3 of 30, which might have created a motivation bias relative to the study outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Wayne Smith, BS, NATA Associate Member, for his consistent support of this project and his ongoing quest for knowledge to enhance the delivery of health care and physical performance.

Footnotes

John Castel is the Chief Technology Officer and Francis Palermo is the Medical Director of Accelerated Care Plus (ACP), the manufacturer of the pens unit used in the study.

References

- 1. Andrews RJ. Neuroprotection Trek: the next generation, Neuromodulation II. Applications: epilepsy, nerve regeneration, neurotrophins. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;993:14-24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bax L, Staes F, Verhagen A. Does neuromuscular electrical stimulation strengthen the quadriceps femoris? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Sports Med. 2005;35(3):191-212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bourjeily-Habr G, Rochester CL, Palermo F, Snyder P, Mohsenin V. Randomized controlled trial of transcutaneous electrical stimulation of the lower extremities in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2002;57(12):1045-1049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boutelle D, Smith B, Malone T. A strength study utilizing the Electro-Stim 180. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1985;7(2):50-53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Caggiano E, Emery T, Shirley S, Craik RL. Effects of electrical stimulation on voluntary contraction for strengthening the quadriceps femoris muscles in aged male population. J Orthop Sports Physical Ther. 1994;20(1):22-28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Calancie B, Needham-Shropshire B, Jakobs P, et al. Involuntary stepping after chronic spinal cord injury: evidence for a central rhythm generator for locomotion in man. Brain. 1994;117:1143-1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cauraugh JH, Kim S. Progress toward motor recovery with active neuromuscular stimulation: muscle activation pattern evidence after a stroke. J Neurol Sci. 2003;207:25-29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen HH, Tourtellotte WG, Frank E. Muscle-derived neurotrophin 3 regulates synaptic connectivity between muscle sensory and motor neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22(9):3512-3519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cooke JD, Brown SH. Movement related phasic muscle activation II: generation of the Triphasic pattern. J Neurophysiol. 1990;63(3):465-472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Currier DP, Lehman J, Lightfoot P. Electrical stimulation in exercise of the quadriceps femoris muscle. Phys Ther. 1979;59(12):1508-1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Currier DP, Mann R. Muscular strength development by electrical stimulation in healthy individuals. Phys Ther. 1983;63(6):915-921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Delitto A, Brown M, Strube MJ, Rose SJ, Lehman RC. Electrical stimulation of quadriceps femoris in an elite weight lifter: a single subject experiment. Int J Sports Med. 1989;10(3):187-191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Delitto A, Rose SJ, McKaven JM. Electrical stimulation versus voluntary exercise in strengthening thigh musculature after anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Phys Ther. 1988;68:660-663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Delitto A, Synder-Mackler L. Two theories of muscle strength augmentation using percutaneous electrical stimulation. Phys Ther. 1990;70(3):158-164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Duan C, Trumble DR, Scalise D, Magovern JA. Intermittent stimulation enhances function of conditioned muscle. Am J Physiol. 1999;276(5):R1534-R1540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eriksson E. Sports injuries of the knee ligaments: their diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation and prevention. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1976;8:133-144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eriksson E, Haggmark T. Comparison of isometric muscle training and electrical stimulation supplementing isometric muscle training in the recovery after major knee ligament surgery. Am J Sports Med. 1979;7:169-171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gartner A, Staiger V. Neurotrophin secretion from hippocampal neurons evoked by long term-potentiation-inducing electrical stimulation patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(9):6386-6391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grillner A, Ekeberg O, El Manira A. Intrinsic function of a neuronal network: a vertebrate central pattern generator. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1998;26:184-197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Halbach JW, Straus D. Comparison of electro-myostimulation to isokinetic training in increasing power knee extensor mechanism. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1980;2:20-24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harman EA, Rosenstein MT, Frykman PN, Rosenstein RM. The effects of arms and countermovement on vertical jumping. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1990;22(6):825-833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hausdorff JM, Ring H. Effects of a new radio frequency-controlled neuroprosthesis on gait symmetry and rhythmicity in patients with chronic hemiparesis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;87(1):4-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Igras E, Foweraker JP, Ware A, Hulliger M. Computer simulation of rhythm-generating networks. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;860:483-485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kesar TM, Perumal R, Jancosko A, et al. Novel patterns of functional electrical stimulation have an immediate effect on dorsiflexor muscle function during gait for people poststroke. Phys Ther. 2010;90(1):55-66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kottink AI, Oostendorp LJ, Buurke JH, Nene AV, Hermens HJ, IJzerman MJ. The orthotic effect of functional electrical stimulation on the improvement of walking in stroke patients with a dropped foot: a systematic review. Artif Organs. 2004;28(6):577-586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kotz YM. Methods of Investigation of Muscular Apparatus. Moscow, Russia: State Central Institute of Physical Culture; 1976 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kotz YM, Chullon VA. The Training of Muscular Power by Method of Electrical Stimulation. Moscow, Russia: State Central Institute of Physical Culture; 1975 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kramer JF, Mendryk SW. Electrical stimulation as a strength improvement technique: a review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1982;4(2):91-98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. MacKay-Lyons M. Central pattern generation of locomotion: a review of the evidence. Phys Ther. 2002;82(1):69-83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Markovic G, Dizdar D, Jukic I, Cardinale M. Reliability and factorial validity of squat and countermovement jump tests. J Strength Cond Res. 2004;18(3):551-555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Molina R, Galan A, Garcia M. Spectral electromyographic changes during a muscular strengthening training based on electrical stimulation. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1997;37:287-295 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moritani T, Devries HA. Neural factors versus hypertrophy in the time course of muscle strength gain. Am J Phys Med. 1979;58:115-130 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Neder JA, Sword D, Ward SA, et al. Home based neuromuscular electrical stimulation as a new rehabilitative strategy for severely disabled patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Thorax. 2002;57:333-337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Newsam CJ, Baker LL. Effect of an electric stimulation facilitation program on quadriceps motor unit recruitment after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:2040-2045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Owens J, Malone T. Treatment parameters of high frequency electrical stimulation as established on the Electro-Stim 180. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1983;4(3):162-168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Palermo FX. Patterned electric stimulation versus upper extremity spasticity in hemiplegia [abstract]. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1987;68:651 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Palermo FX. Patterned electrical stimulation versus torticollis: seven cases [abstract]. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1991;72:796 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Palermo FX. Transcranial direct current stimulation combined with peripheral patterned stimulation in stroke recovery: a case series [abstract]. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2007;88(9):E101-E102 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Palermo FX, Picone K, Freeburg J. Patterned electric stimulation versus torticollis: six cases. Phys Ther. 1991;71(6):S036 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pandyan AD, Granat MH, Stott DJ. Effects of electrical stimulation on flexion contractures in the hemiplegic wrist. Clin Rehabil. 1997;11(2):123-130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ring H, Treger I, Gruendlinger L, Hausdorff JM. Neuroprosthesis for footdrop compared with an ankle-foot orthosis: effects on postural control during walking. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;18(1):41-47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sale DG. Neural adaptation to strength training. In: Komi PV, ed. Strength and Power in Sports. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1992:249-265 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Selverton AI. Modeling of neural circuits: what have we learned? Annu Rev Neurosci. 1993;16:531-546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Soo C-L, Currier DP, Threlkeld AJ. Augmenting voluntary torque of healthy muscle by optimization of electrical stimulation. Phys Ther. 1988;68(3):333-337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stevens JE, Mizner RL, Snyder-Mackler L. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation for quadriceps muscle strengthening after bilateral total knee arthroplasty: a case series. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34:21-29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Trimble MH, Enoka RM. Mechanisms underlying the training effects associated with neuromuscular electrical stimulation. Phys Ther. 1991;71(4):273-280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yan T, Hui-Chan CWY, Li LSW. Functional electrical stimulation improves motor recovery of the lower extremity and walking ability of subjects with first acute stroke. Stroke. 2005;36:80-85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhan WZ, Mantilla CB, Sieck GC. Regulation of neuromuscular transmission by neurotrophins. Sheng Li Xue Bao. 2003;55(6):617-624 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]