Abstract

Context:

Low back pain is one of the most common medical presentations in the general population. It is a common source of pain in athletes, leading to significant time missed and disability. The general categories of treatment for low back pain are medications and therapies.

Evidence acquisition:

Relevant studies were identified through a literature search of MEDLINE and the Cochrane Database from 1990 to 2010. A manual review of reference lists of identified sources was also performed.

Results:

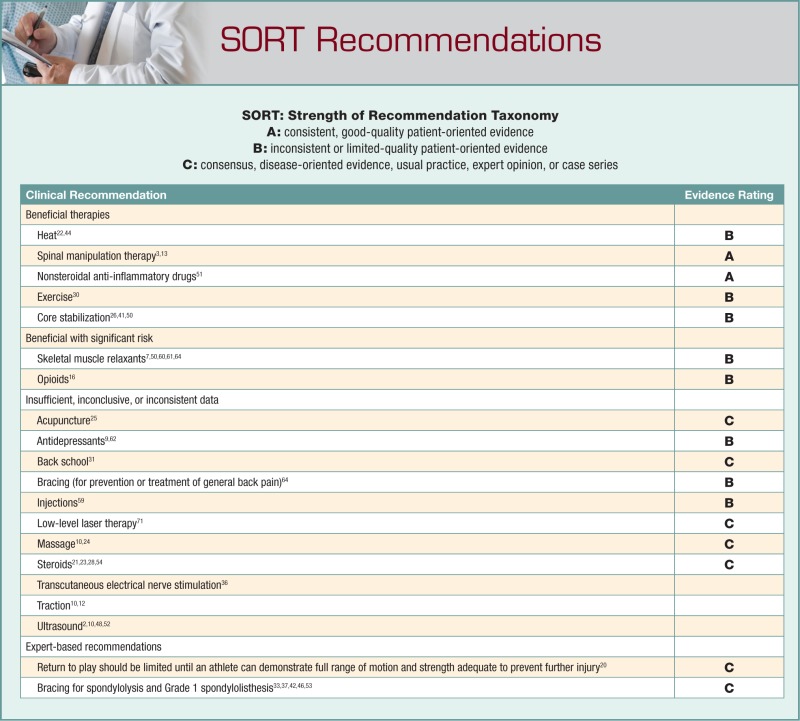

It is not clear whether athletes experience low back pain more often than the general public. Because of a aucity of trials with athlete-specific populations, recommendations on treatments must be made from reviews of treatments for the general population. Several large systemic reviews and Cochrane reviews have compiled evidence on different modalities for low back pain. Superficial heat, spinal manipulation, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and skeletal muscle relaxants have the strongest evidence of benefit.

Conclusions:

Despite the high prevalence of low back pain and the significant burden to the athletes, there are few clearly superior treatment modalities. Superficial heat and spinal manipulation therapy are the most strongly supported evidence-based therapies. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications and skeletal muscle relaxants have benefit in the initial management of low back pain; however, both have considerable side effects that must be considered. Athletes can return to play once they have recovered full range of motion and have the strength to prevent further injury.

Keywords: low back pain, treatment, athletes

Low back pain is the fifth most common reason for all physician visits in the United States.17,29 Approximately one quarter of US adults report having low back pain lasting at least 1 whole day in the past 3 months,17 and 7.6% report at least 1 episode of severe acute low back pain within a 1-year period.8 The prevalence rates of low back pain in athletes range from 1% to 40%.5 Back injuries in the young athlete are a common phenomenon, occurring in 10% to 15% of participants.18 It is not clear if athletes experience low back pain more often than the general population. Comparisons of wrestlers,27 gymnasts,60 and adolescent athletes40 have found back pain more common versus age-matched controls. Other comparisons of athletes and nonathletes have found lower rates of low back pain in athletes than nonathletes.67

Clinical examination and diagnostic skills are essential in the workup of low back pain. Athletes with neurologic compromise, fever, chills, or incontinence of bowel or bladder function or those with mechanism of action that could result in fracture or other serious injuries must first be evaluated for emergent causes. Workup and diagnosis must be individualized on the basis of differential diagnosis.

Because of the limited number of high-quality randomized controlled trials or systemic reviews involving athletes, most of the following recommendations are summaries of the current evidence for back pain in the general population.

Epidemiology

Sports that have higher rates of back pain include gymnastics, diving, weight lifting, golf, American football, and rowing.61 In gymnastics, the incidence of back injuries is 11%. In football linemen, it may be as high as 50%.18 Ninety percent of all injuries of professional golfers involve the neck or back.19 Injury rates for 15- and 16-year-old girls in gymnastics, dance, or gym training are higher than the general population, while cross-country skiing and aerobics are associated with a lower prevalence of low back pain.4 For boys, volleyball, gymnastics, weight lifting, downhill skiing, and snowboarding are associated with higher prevalence of low back pain, while cross-country skiing and aerobics show a lower prevalence.

Back pain is a symptom and has many causes. Muscle strains, ligament sprains, and soft tissue contusions account for as much as 97% of back pain in the general adult population.1 The majority of athletes with low back pain have a benign source of pain.69 Muscle strain may be the most common cause of low back pain in college athletes.35

The clinical spectrum of spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, and pars interarticularis stress fractures may be the most common cause of low back pain in adolescents.47 Repetitive hyperextension of the low back (gymnastics, figure skating, diving, and football linemen) is a risk factor for the development of spondylolysis.39,55

Hyperlordosis (lordotic low back pain) is the second most common cause of adolescent low back pain.18,47 This condition is related to adolescent growth spurts when the axial skeleton grows faster than the surrounding soft tissue, resulting in muscular pain.55 Other causes of low back pain unique to children are vertebral endplate fractures and bacterial infection of the vertebral disk. Adolescents have weaker cartilage in the endplate of the outer annulus fibrosis, allowing avulsion and resulting in symptoms similar to a herniated vertebral disk.58 Additionally, the pediatric lumbar spine has blood vessels that traverse the vertebral bodies and supply the vertebral disk, increasing the chance of developing diskitis.51

Treatment Options

Cold Versus Heat

Cold can be applied to the low back with towels, gel packs, ice packs, and ice massage. Heat methods include water bottles and baths, soft packs, saunas, steam, wraps, and electric pads. There are few high-quality randomized controlled trials supporting superficial cold or heat therapy for the treatment of acute or subacute low back pain. A Cochrane review cited moderate evidence supporting superficial heat therapy as reducing pain and disability in patients with acute and subacute low back pain, with the addition of exercise further reducing pain and improved function.22 The effects of superficial heat seem strongest for the first week following injury.44

Ultrasound

There are no systemic reviews for ultrasound.10 One small nonrandomized trial48 for patients with acute sciatica found ultrasonography superior to sham ultrasonography or analgesics for relief of pain. All patients were prescribed bed rest. For patients with chronic back pain, the small trials were contradictory to whether ultrasonography was any better than sham ultrasonography.2,52

Laser

Low-level laser therapy (LLLT) is a noninvasive light source treatment that generates a single wavelength of light without generating heat, sound, or vibration. Also called photobiology or biostimulation, LLLT may accelerate connective tissue repair and serve as an anti-inflammatory agent. Wavelengths from 632 to 904 nm are used in the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders. A Cochrane review of 7 small studies with a total of 384 patients with nonspecific low back pain of varying durations found insufficient data to either support or refute the effectiveness of LLLT for the treatment of low back pain. Because of the varied length of treatment, LLLT dose, application techniques, and different populations, it was not possible to determine optimal administration of LLLT.71 No side effects were reported.

A recent double-blind randomized placebo-controlled study of 546 patients with acute low back pain (less than 4 weeks) with radiculopathy compared LLLT and nimesulide to nimesulide alone to sham LLLT. Treatment with LLLT and nimesulide improved movement, with more significant reduction in pain intensity and disability and with improvement in quality of life, compared with patients treated only with drugs or placebo LLLT.38

Medications

Steroids

Three small higher quality trials found that systemic corticosteroids were not clinically beneficial compared with placebo when given parenterally or as a short oral taper for acute or chronic sciatica.21,28,49 With acute low back pain and a negative straight-leg raise test, no difference in pain relief through 1 month was found between a single intramuscular injection of methylprednisolone (160 mg) or placebo.23 Glucocorticosteroids are banned by the World Anti-doping Association.70

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

A large Cochrane review of 65 trials (11 237 patients) of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and COX-2 inhibitors in the treatment of acute and chronic low back pain showed that NSAIDs had statistically better effects compared with placebo.51 The benefits included global improvement and less additional analgesia requirement. NSAIDs were associated with higher rate of side effects. There was no strong evidence that any one NSAID or COX-2-selective NSAID is clinically superior to the others. NSAIDs were not superior to acetaminophen, but NSAIDs had more side effects. NSAIDs were not more effective that physiotherapy or spinal manipulation for acute low back pain. COX-2-selective NSAIDs had fewer side effects than nonselective NSAIDs.51

Muscle relaxants

Several systemic reviews have found skeletal muscle relaxants effective for short-term symptomatic relief in acute and chronic low back pain.7,56,65,66 However, the incidence of drowsiness, dizziness, and other side effects is high.66 There is minimal evidence on the efficacy of the antispasticity drugs (dantrolene and baclofen) for low back pain.66

Opioids

A 2007 Cochrane review of opioids for chronic low back pain found that tramadol was more effective than placebo for pain relief and improving function.16 The 2 most common side effects of tramadol were headaches and nausea. One trial comparing opioids to naproxen found that opioids were significantly better for relieving pain but not improving function. Despite the frequent use of opioids for long-term management of chronic LBP, there are few high-quality trials assessing efficacy. The benefits of opioids for chronic LBP remain questionable. There is no evidence that sustained-release opioid formulations are superior to immediate-release formulations for low back pain. Long-acting opioids did not differ in head-to-head trials.9 Opioids are banned by the World Anti-doping Association.70

Antidepressants

A Cochrane review of 10 antidepressant and placebo trials showed no difference in pain relief or depression severity.62 The qualitative analyses found conflicting evidence on the effect of antidepressants on pain intensity in chronic low back pain and no clear evidence that antidepressants reduce depression in chronic low-back-pain patients. Two pooled analyses showed no difference in pain relief between different types of antidepressants and placebo. Another systemic review found different results: Antidepressants were more effective than placebo,9 but the effects were not consistent with all antidepressants. Tricyclic antidepressants were moderately more effective than placebo, but paroxetine and trazodone were not.9 Antidepressants were associated with significantly higher risk for adverse events compared with placebo, with drowsiness, dry mouth, dizziness, and constipation the most commonly reported.54 Duloxetine has recently been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of chronic low back pain and osteoarthritis,63 and evidence suggests effectiveness in chronic low back pain.58,57

Manipulation: Chiropractic, Osteopathic, Manual Physical Therapy

Three systemic reviews3,6,13 analyzed spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) for low back pain, including (1) high-velocity, low-amplitude manipulation of the spinal joints slightly beyond their passive range of motion; (2) high-velocity, low-amplitude technique rotating the thigh and leg; (3) mobilization within passive range of motion; and (4) instrument-based manipulations. There is moderate evidence of short-term pain relief with acute low back pain treated with SMT.6 Chronic low back pain showed moderate improvement with SMT, which is as effective as NSAIDs and more effective than physical therapy in the long term.6 Patients with mixed acute and chronic low back pain had better pain outcomes in the short and long terms compared with McKenzie therapy, medical care, management by physical therapists, soft tissue treatment, and back school.6 SMT was more effective in reducing pain and improving daily activities when compared with sham therapy.3 Dagenais13 found SMT effective in pain reduction in the short-, intermediate-, and long-term management of acute low back pain. However, a Cochrane review in 2004 on SMT in acute and chronic low back pain concluded that there was no difference in pain reduction or ability to perform daily activities with SMT or standard treatments (medications, physical therapy, exercises, back school, or the care of a general practitioner).3

Injections

A 2008 Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials for subacute and chronic low back pain included 18 trials of 1179 participants.59 Studies that compared intradiscal injections, prolotherapy, ozone, sacroiliac joint injections, or epidural steroids for radicular pain were excluded unless injection therapy with another pharmaceutical agent was part of one of the treatment arms. Corticosteroids, local anesthetics, indomethacin, sodium hyaluronate, and B12 were used. Of 18 trials, 10 were rated for high methodological quality. Statistical pooling was not possible because of clinical heterogeneity in the trials yielding no strong evidence for or against the use of injection therapy.59

Botulinum toxin was compared in a 2011 Cochrane review that found significant study heterogeneity and low- to very-low-quality evidence for botulinum toxin in the treatment of nonspecific chronic low back pain.68 One new trial has shown no benefit with botulinum toxin injections for myofascial pain syndrome.15

A small study34 on spinal injections in 32 athletes with acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain with sciatic nerve involvement showed that only 14% were able to return to participation.

Acupuncture

Thirty-five randomized controlled trials did not allow firm conclusions for the effectiveness of acupuncture for acute low back pain.25 For chronic low back pain, acupuncture is more effective for pain relief and functional improvement than no treatment or sham treatment in the short term only. Acupuncture is not more effective than other conventional or alternative treatments.25

Massage

Massage might be beneficial for patients with subacute and chronic nonspecific low back pain, especially when combined with exercises and education.24 Acupressure or pressure point massage technique was more effective than classic massage. A second systemic review found insufficient evidence to determine efficacy of massage for acute low back pain.10 Evidence was insufficient to determine effects of the number or duration of massage sessions.

Traction

A meta-analysis found traction no more effective than placebo, sham, or no treatment for any outcome for low back pain with or without sciatica.12 The results consistently indicated that continuous or intermittent traction as a single treatment for low back pain is not effective.12 Side effects included worsening of signs and symptoms and increased subsequent surgery; however, the reports are inconsistent.10

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation

Evidence from the small number of placebo-controlled trials does not support the use of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in the routine management of chronic low back pain.36 Evidence from single lower quality trials is insufficient to accurately judge efficacy of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation versus other interventions for chronic low back pain or acute low back pain.10

Bracing/Lumbar Supports

Braces are not effective in preventing back pain.64 However, there is conflicting evidence to whether braces are effective supplements to other preventive interventions.64 Bracing, in combination with activity restriction, is effective in the treatment of spondylolysis in adolescents.33,42,46,53 A meta-analysis of 15 observational spondylolysis and grade 1 spondylolisthesis treatment studies did not find a significant improvement in rates of healing with bracing when compared with conservative treatment without bracing.37 Most experts recommend surgical consultation for spondylolisthesis with 50% slippage or more (grade 3 and higher).46

Back Schools

There is moderate evidence suggesting that back schools reduce pain and improve function and return-to-work status when compared with exercises, manipulation, myofascial therapy, advice, or placebo.31 The patients benefiting from back schools had chronic and recurrent nonspecific low back pain in an occupational setting.31

Exercise

Exercise therapy appears to be slightly effective at decreasing pain and improving function in adults with chronic low back pain.30 In subacute low back pain, there is weak evidence that a graded activity program improves absenteeism.30 In acute low back pain, exercise therapy was no better than no treatment or conservative treatments. Exercise therapy using individualized regimens, supervision, stretching, and strengthening was associated with the best outcomes. The addition of exercise to other noninvasive therapies was associated with small improvements in pain and function.

A randomized single-blind controlled trial compared manual therapy and spinal stabilization rehabilitation to control (education booklet) for chronic back pain.26 Spinal stabilization rehabilitation was more effective than either manipulation or the education booklet in reducing pain, disability, medication intake, and improving the quality of life for chronic low back pain.26 A systemic review found segmental stabilizing exercises more effective in reducing the recurrence of pain in acute low back pain; however, exercises were no better than treatment by general practitioner in reducing short-term disability and pain.50 For chronic low back pain, segmental stabilizing exercises were more effective than treatment from general practitioners but no more effective than exercises using devices, massage, electrotherapy, or heat.50 In a trial of 30 hockey players, dynamic muscular stabilization techniques (an active approach to stabilization training) were more effective than a combination of ultrasound and short-wave diathermy and lumbar strengthening exercises.41

The McKenzie method45 uses clinical examination to separate patients with low back pain into subgroups (postural, dysfunction, and derangement) to determine appropriate treatment. The goal is symptom relief through individualized treatment by the patient at home. The McKenzie method is not exclusively extension exercises; it emphasizes patient education to decrease pain quickly, restore function, minimize the number of visits to the clinic, and prevent recurrences.45 Two systemic reviews have compared the McKenzie method with different conclusions.11,43 Clare et al11 concluded that McKenzie therapy resulted in decreased short-term (less than 3 months) pain and disability when compared with NSAIDs, educational booklet, back massage with back care advice, strength training with therapist supervision, and spinal mobilization. Machado et al43 concluded that the McKenzie method does not produce clinically worthwhile changes in pain and disability when compared with passive therapy and advice to stay active for acute LBP.

A separate review evaluated bed rest versus activity in acute low back pain and sciatica.14 There were small benefits in pain relief and functional improvement from staying active compared with rest in bed.

Return To Play

Return-to-play (RTP) guidelines are difficult to standardize for low back pain because of a lack of supporting evidence. A commonly encountered question is, can athletes play through pain? There is no simple answer to this question. For example, an athlete with suspected spondylolysis is generally advised that he or she should not play through pain, while athletes with chronic low back pain from muscular or ligamentous strain may continue to practice, exercise, and compete. However, there is little evidence to support either of these approaches. These athletes should always be monitored for their safety.

Expert opinion guidelines on RTP time frames have been published for lumbar spine conditions.20 Lumbar strains should achieve full range of motion before RTP. Patients with spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis (grade 1) should rest 4 to 6 weeks and then demonstrate full range of motion and pain-free extension before RTP.22 Athletes with herniated lumbar disks should rest 6 to 12 weeks following surgical treatment, while those with spinal fusion should wait 1 year to return to activity.20 Many surgeons advise against return to contact sports following spinal fusion.20 Iwamoto et al32 reviewed conservative and surgical treatments in athletes with lumbar disc herniation and time to return to previous level of sports activity. Seventy-nine percent of conservatively treated athletes returned in an average of 4.7 months, while 85% of those treated with microdiscectomy returned in 5.2 to 5.8 months. Sixty-nine percent of percutaneous discectomies returned in 7 weeks to 12 months.32

Conclusions

Low back pain is a common problem in athletes. Clinicians must be able to identify athletes with high-risk low back injuries. The treatments available to the clinician are broad, but very few treatment modalities have evidence of efficacy.

References

- 1. An HS, Jenis LG, Vaccaro AR. Adult spine trauma. In: Beaty JH, ed. Orthopaedic Knowledge Update 6. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1999:653-671 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ansari NN, Ebadi S, Talebian S, et al. A randomized, single blind placebo controlled clinical trial on the effect of continuous ultrasound on low back pain. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;46(6):329-336 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Assendelft WJJ, Morton SC, Yu EI, Suttorp MJ, Shekelle PG. Spinal manipulative therapy for low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(1):CD000447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Auvinen JP, Tammelin TH, Taimela SP, et al. Musculoskeletal pain in relation to different sport and exercise activities in youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(11):1890-1900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bono C. Low back pain in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(2):382-396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bronfort G, Haas M, Evans RL, Bouter LM. Efficacy of spinal manipulation and mobilization for low back pain and neck pain: a systematic review and best evidence synthesis. Spine J. 2004;4:335-356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Browning R, Jackson JL, O’Malley PG. Cyclobenzaprine and back pain: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1613-1620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carey TS, Evans AT, Hadler NM, et al. Acute severe low back pain: a population-based study of prevalence and care-seeking. Spine. 1996;21:339-344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chou R, Huffman LH. Medications for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:505-514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chou R, Huffman LH. Nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:492-504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Clare HA, Adams R, Maher CG. A systematic review of efficacy of McKenzie therapy for spinal pain. Aust J Physiother. 2004;50:209-216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clarke JA, van Tulder MW, Blomberg SEI, et al. Traction for low-back pain with or without sciatica. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD003010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dagenais S, Gay RE, Tricco AC, Freeman MD, Mayer JM. NASS Contemporary concepts in spine care: spinal manipulation therapy for acute low back pain. Spine J. 2010;10:918-940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dahm KT, Brurberg KG, Jamtvedt G, Hagen KB. Advice to rest in bed versus advice to stay active for acute low-back pain and sciatica. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(6):CD007612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Andes J, Adsuara VM, Palmisani S, Villanueva V, López-Alarcón MD. A double-blind, controlled, randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of botulinum toxin for the treatment of lumbar myofascial pain in humans. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010;35(3):255-260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deshpande A, Furlan AD, Mailis-Gagnon A, Atlas S, Turk D. Opioids for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD004959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Martin BI. Back pain prevalence and visit rates: estimates from US national surveys, 2002. Spine. 2006;31:2724-2727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. d’Hemecourt PA, Gerbino PG, Micheli LJ. Back injuries in the young athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2000;19:663-679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Duda M. Golfers use exercise to get back in the swing. Phys Sportsmed. 1989;17:109-113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eck JC, Riley LH., III Return to play after lumbar spine conditions and surgeries. Clin Sports Med. 2004;23:367-379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Finckh A, Zufferey P, Schurch MA, Balague F, Waldburger M, So AK. Short-term efficacy of intravenous pulse glucocorticoids in acute discogenic sciatica: a randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2006;31:377-381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. French SD, Cameron M, Walker BF, Reggars JW, Esterman AJ. A Cochrane review of superficial heat or cold for low back pain. Spine. 2006;31(9):998-1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Friedman BW, Holden L, Esses D, et al. Parenteral corticosteroids for emergency department patients with non-radicular low back pain. J Emerg Med. 2006;31:365-370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Furlan AD, Imamura M, Dryden T, Irvin E. Massage for low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD001929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Furlan AD, van Tulder MW, Cherkin D, et al. Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1):CD001351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goldby LJ, Moore AP, Doust J, Trew ME. A randomized controlled trial investigating the efficiency of musculoskeletal physiotherapy on chronic low back disorder. Spine. 2006;31:1083-1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Granhed H, Morelli B. Low back pain among retired wrestlers and heavyweight lifters. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16:530-533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Haimovic IC, Beresford HR. Dexamethasone is not superior to placebo for treating lumbosacral radicular pain. Neurology. 1986;36:1593-1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hart LG, Deyo RA, Cherkin DC. Physician office visits for low back pain: frequency, clinical evaluation, and treatment patterns from a US national survey. Spine. 1995;20:11-19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hayden J, van Tulder MW, Malmivaara A, Koes BW. Exercise therapy for treatment of non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3):CD000335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Heymans MW, van Tulder MW, Esmail R, Bombardier C, Koes BW. Back schools for non-specific low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4):CD000261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Iwamoto J, Sato Y, Takeda T, Matsumoto H. The return to sports activity after conservative or surgical treatment in athletes with lumbar disk herniation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;89(12):1030-1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Iwamoto J, Takeda T, Wakano K. Returning athletes with severe low back pain and spondylolysis to original sporting activities with conservative treatment. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2004;14:346-351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jackson DW, Rettig A, Wiltse LL. Epidural cortisone injections in the young athletic adult. Am J Sports Med. 1980;8(4):239-243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Keene JS, Albert MJ, Springer SL, Drummond DS, Clancy WG., Jr Back injuries in college athletes. J Spinal Disord. 1989;2:190-195 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Khadilkar A, Odebiyi DO, Brosseau L, Wells GA. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) versus placebo for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD003008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Klein G, Mehlman CT, McCarty M. Nonoperative treatment of spondylolysis and grade I spondylolisthesis in children and young adults: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29(2):146-156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Konstatntinovic LM, Kanjuh ZM, Milovanovic AN, et al. Acute low back pain with radiculopathy: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Photomedicine Laser Surg. 2010;28(4):553-560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kraft DE. Low back pain in the adolescent athlete. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2002;49:643-653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kujala UM, Taimela S, Erkintalo M, Salminen JJ, Kaprio J. Low-back pain in adolescent athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996;28:165-170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kumar S, Sharma VP, Negi MPS. Efficacy of dynamic muscular stabilization techniques (DMST) over conventional techniques in rehabilitation of chronic low back pain. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23(9):2651-2659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kurd MF, Patel D, Norton R, et al. Nonoperative treatment of symptomatic spondylolysis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20:560-564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Machado LA, de Souza MS, Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML. The McKenzie method for low back pain: a systematic review of the literature with a meta-analysis approach. Spine. 2006;31:E254-E262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mayer JM, Ralph L, Look M, et al. Treating acute low back pain with continuous low-level heat wrap therapy and/or exercise: a randomized controlled trial. Spine J. 2005;5:395-403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. McKenzie Institute International The McKenzie method. http://www.mckenziemdt.org/approach.cfm?section=int Accessed November 1, 2010

- 46. McTimoney CA, Micheli LJ. Current evaluation and management of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2003;2(1):41-46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Micheli LJ, Wood R. Back pain in young athletes: significant differences from adults in causes and patterns. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:15-18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nwuga VC. Ultrasound in treatment of back pain resulting from prolapsed intervertebral disc. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1983;64:88-89 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Porsman O, Friis H. Prolapsed lumbar disc treated with intramuscularly administered dexamethasonephosphate: a prospectively planned, double-blind, controlled clinical trial in 52 patients. Scand J Rheumatol. 1979;8:142-144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rackwitz B, de Bie R, Limm H, von Garnier K, Ewert T, Stucki G. Segmental stabilizing exercises and low back pain: what is the evidence? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Clin Rehabil. 2006;20(7):553-567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Roelofs PD, Deyo RA, Koes BW, Scholten RJ, van Tulder MW. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain: an updated Cochrane review. Spine. 2008;33:1766-1774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Roman MP. A clinical evaluation of ultrasound by use of a placebo technic. Phys Ther Rev. 1960;40:649-652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sairyo K, Sakai T, Yasui N. Conservative treatment of lumbar spondylolysis in childhood and adolescence: the radiological signs which predict healing. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:206-209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Salerno SM, Browning R, Jackson JL. The effect of antidepressant treatment on chronic back pain: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:19-24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sassmannshausen G, Smith BG. Back pain in the young athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2002;21:121-132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Schnitzer TJ, Ferraro A, Hunsche E, Kong SX. A comprehensive review of clinical trials on the efficacy and safety of drugs for the treatment of low back pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:72-95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Skljarevski V, Desaiah D, Liu-Seifert H, et al. Efficacy and safety of duloxetine in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35(13): E578-E585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Skljarevski V, Zhang S, Desaiah D, et al. Duloxetine versus placebo in patients with chronic low back pain: a 12-week, fixed-dose, randomized, double-blind trial. J Pain. 2010;11(12):1282-1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Staal JB, de Bie R, de Vet HCW, Hildebrandt J, Nelemans P. Injection therapy for subacute and chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD001824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sward L, Hellstrom M, Jacobsson B, Nyman R, Peterson L. Disc degeneration and associated abnormalities of the spine in elite gymnasts: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Spine. 1991;16:437-443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Trainor TJ, Trainor MA. Etiology of low back pain in athletes. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2004;3:41-46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Urquhart DM, Hoving JL, Assendelft WJJ, Roland M, van Tulder MW. Antidepressants for non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD001703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. US Food and Drug Administration FDA clears Cymbalta to treat chronic musculoskeletal pain [press release]. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm232708.htm Accessed November 15, 2010

- 64. van Duijvenbode I, Jellema P, van Poppel M, van Tulder MW. Lumbar supports for prevention and treatment of low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD001823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. van Tulder MW, Koes BW, Bouter LM. Conservative treatment of acute and chronic nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the most common interventions. Spine. 1997;22:2128-2156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. van Tulder MW, Touray T, Furlan AD, Solway S, Bouter LM. Muscle relaxants for non-specific low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(4):CD004252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Videman T, Sarna S, Battie MC, et al. The long-term effects of physical loading and exercise lifestyles on backrelated symptoms, disability, and spinal pathology among men. Spine. 1995;20:699-709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Waseem Z, Boulias C, Gordon A, Ismail F, Sheean G, Furlan AD. Botulinum toxin injections for low-back pain and sciatica. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(1):CD008257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Watkins RG, Dillin WM. Lumbar spine injuries. In: Fu FF, Stone DA, eds. Sports Injuries: Mechanisms, Prevention, Treatment. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1994:877-948 [Google Scholar]

- 70. World Anti-doping Agency The world anti-doping code. http://www.wada-ama.org/Documents/World_Anti-Doping_Program/WADP-Prohibited-list/To_be_effective/WADA_Prohibited_List_2011_EN.pdf Accessed March 1, 2011

- 71. Yousefi-Nooraie R, Schonstein E, Heidari K, et al. Low level laser therapy for nonspecific low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD005107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]