Cytokinesis is a fundamental step of cell proliferation, and its high-fidelity completion is crucial for stable maintenance of the genome (Ganem et al., 2007; Lacroix and Maddox, 2012). Anti-parallel microtubule bundle structures such as the central spindle and the midbody play various important roles throughout cytokinesis, from positioning of cleavage furrow to final separation of the two daughter cells (Barr and Gruneberg, 2007; Glotzer, 2009; Fededa and Gerlich, 2012). Although a large number of different factors that are important for abscission, including membrane trafficking machinery, localise to the midzone during cytokinesis (Caballe and Martin-Serrano, 2011; Guizetti and Gerlich, 2010; Neto and Gould, 2011), here we focus on the current understanding of protein–protein interactions between microtubule organisers and their regulators that form cytokinetic microtubule structures.

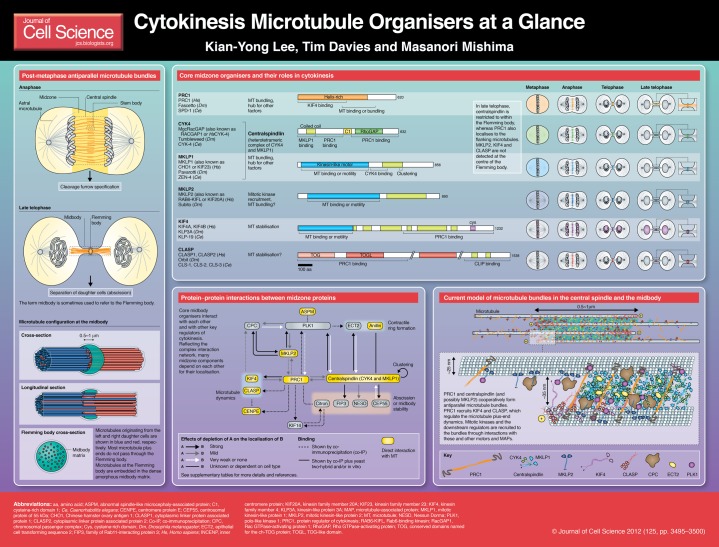

During anaphase, a barrel-shaped array of bundles of interpolar microtubules appears between the segregating chromosomes (Barr and Gruneberg, 2007; Glotzer, 2009). Although this structure has been referred to in different ways, such as ‘midzone microtubule bundles’, here we call it the ‘central spindle’ (Douglas and Mishima, 2010). It is made of two sets of microtubules that come from each half of the mitotic spindle with their plus ends at the centre and form interdigitating anti-parallel overlaps referred to as the ‘stem body’ (see Poster). In some cell types, especially in larger cells such as blastomeres of sea urchin embryos, growth of non-spindle microtubules that emanate from spindle poles (astral microtubules) towards the cell cortex is also promoted after the onset of anaphase (von Dassow et al., 2009). When astral microtubules from opposite poles meet at the equatorial region, they also form anti-parallel bundles. Irrespective of their origins, both of these anti-parallel microtubule bundle structures play important roles in specifying the cleavage furrow by recruiting cytokinesis effectors, such as activator(s) of Rho GTPase, the master regulator of contractile ring formation (Piekny et al., 2005).

The ingressing cleavage furrow gathers both the aster-derived equatorial microtubule bundles and the central spindle into a single compact microtubule bundle, which, upon completion of furrowing, tightly contacts the surrounding plasma membrane in the intercellular bridge (Buck and Tisdale, 1962) (see Poster). Often, a distinct disk-like expansion of the intercellular bridge is observed, which corresponds to the central zone, where anti-parallel microtubules overlap. Again, there has been a history of ambiguity in terminology. Here we use ‘midbody’ to refer the entire microtubule bundle structure that is retained at the intercellular bridge after furrow completion and call the central distinct structure the ‘Flemming body’ (Mollinari et al., 2002; Paweletz, 1967). The intercellular bridge is maintained for up to several hours until the final separation of sister cells (abscission) occurs and is believed to serve as the platform for the membrane trafficking and fusion events that are essential for abscission.

Using traditional electron microscopy (EM), overlapping anti-parallel microtubules in the stem body and the Flemming body were shown to be embedded in highly electron-dense matrices (‘stem body matrix’ and ‘midbody matrix’, respectively) (McIntosh and Landis, 1971). Dense matrix material also fills the space between the microtubule bundle and the plasma membrane (Buck and Tisdale, 1962). A recent cryo-electron tomography study confirmed that this dense region is not just caused by staining with heavy metals, but actually reflects the deposition of high-density matrix material (Elad et al., 2011). Indeed, owing to this crowding effect, antibodies cannot easily access the inside of the Flemming body, resulting in a dark gap in immunofluorescence staining of tubulin by epitope masking (Saxton and McIntosh, 1987). This means that it is essential to use a combination of immunofluorescence and GFP tagging to determine the localisation of proteins to the Flemming body (Arnaud et al., 1998). It remains unclear whether the midbody matrix is a uniform amorphous aggregation of the matrix substances, or whether it has a regular substructure.

A number of molecules have been identified at the central anti-parallel overlap zone of the central spindle and the midbody. These can be classified into three categories. The first class includes the core microtubule organisers, such as protein regulator of cytokinesis 1 (PRC1) and centralspindlin. The second category is made up of their upstream regulators, represented by mitotic kinases, such as Aurora B kinase, which is a component of the chromosomal passenger complex (CPC) (Ruchaud et al., 2007), and polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) (Archambault and Glover, 2009). The third class comprises the downstream effectors, including epithelial cell-transforming sequence 2 oncogene (ECT2), which is the major activator of Rho GTPase, and centrosomal protein of 55 kDa (CEP55), which is a key to recruitment of abscission factors to the midbody. However, this classification is not always obvious because the relationship of these factors to each other is not a simple cascade, but instead comprises a complex network with multiple feedback loops as described below.

Conserved midzone motors and microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs)

Generally speaking, the organisation of a microtubule-based structure depends on the combination of various elementary steps involved in microtubule dynamics, such as nucleation, elongation, end-capping, depolymerisation, bundling, sliding, etc. The microtubules in the spindle midzone are stabilised after anaphase onset (Murthy and Wadsworth, 2008), although the underlying molecular mechanism is not clear. It remains to be determined whether a stabilisation of interpolar microtubules that pre-exist from metaphase is sufficient for the formation of the central spindle or whether de novo microtubule polymerisation (Uehara and Goshima, 2010) is also required. The molecular details of the anchoring of the microtubule minus ends or their stabilisation without a specific anchoring structure are also unclear, although γ-tubulin (Julian et al., 1993; Shu et al., 1995) and its associated proteins, such as augmin (Uehara et al., 2009) and minus-end-directed motor kinesin-14 (Cai et al., 2010), as well as the recently identified microtubule minus-end stabiliser patronin (Goodwin and Vale, 2010) have been suggested to be involved. By contrast, the roles of motors and microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) that localise to the central anti-parallel overlaps have been better characterised as described below. The localisation of these factors has been studied using different methods and in different cell types (as discussed below and summarised on the Poster), and has recently been confirmed in a comparative survey in HeLa cells (Hu et al., 2012).

PRC1

PRC1 (Jiang et al., 1998; Verbrugghe and White, 2004; Vernì et al., 2004) is a microtubule bundling protein, which belongs to a highly conserved family of MAPs that includes plant MAP65 (Hamada, 2007; Sasabe and Machida, 2006) and yeast Ase1p (Schuyler et al., 2003). Crossbridges of ∼35 nm length are observed between anti-parallel microtubules that are bundled by PRC1 (Mollinari et al., 2002; Subramanian et al., 2010). Although the C-terminal portion of PRC1 is predicted to be unfolded, the remainder of the molecule is predicted to form a rod-like dimer consisting of repeated triple helix bundles similar to an actin bundling protein, α-actinin (Li et al., 2007). The microtubule-binding region of PRC1 has been mapped to the C-terminal half of the molecule, which covers the unfolded tail and the adjacent part of the α-helical region (Mollinari et al., 2002; Subramanian et al., 2010). The triple helix bundle structure in the microtubule-binding domain of human PRC1 has been confirmed by X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM helical reconstruction (Subramanian et al., 2010).

PRC1 is essential for the formation of the central spindle in vivo (Mollinari et al., 2002; Verbrugghe and White, 2004; Vernì et al., 2004). Before the onset of anaphase, PRC1 is diffusely localised throughout the cytoplasm and only a minor population associates weakly with the entire spindle. At anaphase onset, PRC1 rapidly accumulates to the spindle midzone, forming the central spindle. Phosphorylation by cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) has a crucial role in this temporal regulation (Jiang et al., 1998; Mollinari et al., 2002; Zhu and Jiang, 2005). Although PRC1 is enriched in the stem body and the Flemming body, its localisation is not as restricted as that of centralspindlin, another key cytokinetic factor described below (Elad et al., 2011). In vitro experiments at the single molecule level reveal that both PRC1 and Ase1p move diffusively along a single microtubule and have a preference for anti-parallel bundling compared with parallel bundling (Bieling et al., 2010; Kapitein et al., 2008; Subramanian et al., 2010). PRC1 interacts with various motors and MAPs as discussed below.

Centralspindlin

Centralspindlin is another microtubule-bundling protein that is critical for the formation of the central spindle. It is a stable 2∶2 heterotetrameric complex of a kinesin-6 orthologous to mammalian mitotic kinesin-like protein 1 (MKLP1) and a Rho-family GTPase-activating protein (RhoGAP) orthologous to Caenorhabditis elegans CYK-4 (CYK4) (Mishima et al., 2002; Somers and Saint, 2003). In mitotic cells, the majority of MKLP1 and CYK4 are in the centralspindlin complex and there is no clear evidence for the presence of free components. The motor domain of MKLP1 possesses the microtubule plus-end-directed motor activity (Hizlan et al., 2006; Mishima et al., 2004; Nislow et al., 1992), which is essential for proper microtubule bundle formation and deposition of the midbody matrix (Matuliene and Kuriyama, 2002). The neck region of MKLP1, which links the motor domain to a relatively short coiled-coil stalk domain, is unusually long and contains the binding site for CYK4 (Mishima et al., 2002; Pavicic-Kaltenbrunner et al., 2007; Somers and Saint, 2003). Both subunits are vital for microtubule bundling in vitro and central spindle formation in vivo. The atomic structure of centralspindlin is not known, except for the GAP domain of CYK4, whose target Rho-family GTPase is under debate (Canman et al., 2008; Jantsch-Plunger et al., 2000; Miller and Bement, 2009; Yamada et al., 2006; Zavortink et al., 2005). Similar to PRC1, the interaction of centralspindlin with microtubules is suppressed by CDK1 phosphorylation before anaphase onset (Goshima and Vale, 2005; Mishima et al., 2004). The heterotetrameric centralspindlin forms higher-order clusters in a manner that is regulated by Aurora B kinase and 14-3-3 proteins (Douglas et al., 2010; Hutterer et al., 2009). This clustering activity is essential for its processive motility in vitro and for its distinct sharp accumulation to the centre of the central spindle in vivo (Hutterer et al., 2009). Centralspindlin also interacts with a number of downstream cytokinesis regulators and effectors as well as with PRC1 (see below).

KIF4

Another midzone motor is the kinesin-4 family member KIF4, which has an N-terminal motor domain followed by a long coiled-coil tail (∼100 nm and longer than that of the conventional kinesin) that is responsible for its dimerisation (Sekine et al., 1994). It moves along the microtubules towards their plus ends and upon its accumulation at the plus end, reduces microtubule polymerisation and depolymerisation dynamics (Bieling et al., 2010; Bringmann et al., 2004). KIF4 was the first kinesin found to associate with mitotic chromosomes and was thus termed chromokinesin (Wang and Adler, 1995). After anaphase onset, a subpopulation of KIF4 accumulates at the central spindle and the midbody (Wang and Adler, 1995). Reflecting this localisation pattern, KIF4 is involved in multiple steps of cell division, including the accurate formation of the central spindle (D’Avino et al., 2007; Kurasawa et al., 2004; Mazumdar et al., 2006; Mazumdar et al., 2004; Williams et al., 1995; Zhu and Jiang, 2005). KIF4 depletion causes abnormal elongation of the central spindle with unfocused microtubule overlaps (Hu et al., 2011). Its interaction with PRC1 has been proposed to be important for cytokinesis (see below).

MKLP2

Mitotic kinesin-like protein 2 (MKLP2) is a less conserved member of the kinesin-6 family, which, in contrast to MKLP1, has not been reported to form a stable complex with other polypeptides. MKLP2 is crucial for the relocation of the CPC from the centromere to the central spindle (Cesario et al., 2006; Gruneberg et al., 2004; Hümmer and Mayer, 2009) and for the appropriate localisation of PLK1 to the spindle midzone (Cesario et al., 2006; Neef et al., 2003). In contrast to centralspindlin, MKLP2 localises to regions adjacent to the Flemming body during late telophase. Although C. elegans does not have the MKLP2 orthologue, vertebrates have a related molecule MPP1, which is also localised to the spindle midzone and required for proper cytokinesis (Abaza et al., 2003).

CLASP

CLASP is a microtubule plus-end tracking protein that contains repeats of TOG and TOG-like domains, and is orthologous to mammalian cytoplasmic linker-associated protein 1 and 2 (CLASP1 and CLASP2) (Akhmanova and Steinmetz, 2008; Slep, 2009). In addition to its function in the regulation of interphase microtubule dynamics, CLASP also controls the architecture of the bipolar mitotic spindle (Walczak, 2005) and the central spindle (Inoue et al., 2000; Inoue et al., 2004). The central spindle localisation of CLASP depends upon its interaction with PRC1 (Liu et al., 2009), similarly to its Schizosaccharomyces pombe orthologue cls1p (also called peg1p) (Bratman and Chang, 2007). Depletion of one of the three CLASPs in C. elegans causes a synthetic cytokinesis failure in PRC1 mutant embryos, which show only mild cytokinesis failure in the first cell division (Bringmann et al., 2007).

Other MAPs and kinesins

ASPM, the mammalian homologue of a Drosophila centrosomal MAP abnormal spindle (Paramasivam et al., 2007), and other kinesin-like motors, including those belonging to the kinesin-3 class [KIF14, KIF13A and GAKIN (also known as KIF13B)] (Gruneberg et al., 2006; Sagona et al., 2010; Unno et al., 2008), the kinesin-7 class (CENP-E, also known as KIF10) (Brown et al., 1994) and the kinesin-8 class (Klp67A) (Savoian et al., 2004), have also been reported to localise to the centre of the central spindle and the midbody. Their roles in organisation of the midzone microtubule bundles are still unclear.

Protein–protein interactions between spindle midzone proteins

As discussed above, the assembly of the central spindle and the midbody depends on multiple microtubule modulators and their regulators. Although the biophysical details of the effects of individual factors on microtubule dynamics or organisation remain to be clarified, current research efforts are shifting towards investigating how these factors cooperate with each other. However, this is a challenging goal because they are not merely interacting with each other in a simple cascade, but instead form a complex network with multiple feedback loops. The fact that many of these factors also directly interact with microtubules as well as with each other adds further complexity. An important test for the functional significance of an interaction between midzone proteins is to determine how the localisation of a protein is affected by depletion of another protein (localisation epistasis). However, this analysis faces serious limitations when the roles of hub factors, such as PRC1 or centralspindlin, which interact with many different proteins, are to be dissected. Ultimately, we need to devise a tool to specifically disrupt the interaction between two proteins without affecting any other functions, such as the generation of ‘separation-of-function’ mutants, ideally in a temporally controlled manner. Our current knowledge on the interactions and localisation epistasis between the midzone proteins is discussed below and summarised on the Poster. A more complete survey that also includes additional midzone proteins not discussed here can be found in supplementary material Tables S1 and S2.

Interactions between midzone organisers and their upstream and downstream factors

Interactions between core midzone organisers and their upstream regulators, such as mitotic kinases, or downstream factors, such as Rho pathway regulators, are relatively well established. Aurora B kinase, which as a CPC component controls various aspects of mitotic progression, is recruited to the central spindle by MKLP2 after anaphase onset, although it is unclear which of the CPC subunits directly interacts with MKLP2 (Gruneberg et al., 2004; Hümmer and Mayer, 2009). It also remains to be determined how the CPC is recruited to the central spindle in organisms that lack MKLP2, such as C. elegans, although a direct interaction between AIR-2 (its Aurora B orthologue) and ZEN-4 (its MKLP1 orthologue) has been reported (Severson et al., 2000). PLK1 is recruited to the central spindle through the binding sites that PLK1 itself produces on PRC1 (Neef et al., 2007) and MKLP2 (Neef et al., 2003) by phosphorylation.

The recruitment of downstream effectors for cleavage furrow induction and abscission also depend on their direct interactions with the midzone motors. For example, ECT2, a major activator of Rho GTPase during cytokinesis, directly interacts with CYK4, and this interaction plays a crucial role in the establishment of the equatorial zone of active Rho, which specifies the division plane (Chalamalasetty et al., 2006; Kamijo et al., 2006; Nishimura and Yonemura, 2006; Somers and Saint, 2003; Yüce et al., 2005; Zhao and Fang, 2005). CYK4 also interacts with a multifunctional contractile ring protein, anillin (D’Avino et al., 2008; Gregory et al., 2008; Piekny and Maddox, 2010). In late telophase, CEP55, an adaptor protein that is essential for midbody recruitment of the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) proteins (Caballe and Martin-Serrano, 2011), localises to the Flemming body by directly interacting with MKLP1 in a manner that is negatively regulated by PLK1-mediated phosphorylation (Bastos and Barr, 2010; Zhao et al., 2006). FIP3, another adaptor protein that interacts with Arf6 and Rab11 GTPases, competes with ECT2 for CYK4 binding and localises to the Flemming body as ECT2 leaves in late telophase (Simon et al., 2008). Interaction between Arf6 and MKLP1 is important for post-mitotic stable maintenance of the midbody and for successful abscission (Makyio et al., 2012; Joseph et al., 2012). In addition, a carbohydrate-binding protein Nessun Dorma (NESD) binds centralspindlin and plays a role in late cytokinesis (Montembault et al., 2010). Another midzone factor, citron kinase, which regulates late cytokinesis events through Rho (Bassi et al., 2011; Gai et al., 2011), depends on KIF14 for its midzone localisation (Gruneberg et al., 2006).

Interaction between PRC1 and KIF4

Dissecting the roles of protein–protein interactions between midzone organisers is even more challenging. A relatively well-characterised interaction among the microtubule modulators is the one between PRC1 and KIF4. This interaction can be detected both by co-immunoprecipitation and yeast two-hybrid assays and is thus likely to be direct (Kurasawa et al., 2004). CDK1 negatively regulates this interaction by phosphorylating PRC1 (Zhu and Jiang, 2005; Zhu et al., 2006). Although the central spindle localisation of KIF4 is lost when PRC1 is depleted, PRC1 still localises to the central spindle and the midbody in the absence of KIF4, albeit in a broadened pattern (Zhu and Jiang, 2005). This observation could reflect the role of the PRC1–KIF4 interaction in transporting PRC1 to the plus ends of microtubules (Zhu and Jiang, 2005). However, aberrant PRC1 localisation in the absence of KIF4 can also be explained by an increase in the length of the microtubule overlap (Hu et al., 2011), which is consistent with the in vitro observation that PRC1 and KIF4 have a combinatorial effect in regulating the length of the anti-parallel overlap (Bieling et al., 2010). Further study is needed to clarify the in vivo importance of their direct interaction because a KIF4 construct that lacks the C-terminal tail and thus does not bind PRC1 can still tightly focus itself and PRC1 to the centre of the central spindle (Hu et al., 2011).

Interaction between PRC1 and centralspindlin

PRC1 has also been reported to interact with centralspindlin on the basis of co-immunoprecipitation experiments in HeLa cell lysates (Ban et al., 2004; Gruneberg et al., 2006; Kurasawa et al., 2004). PRC1 was also found to interact with the CYK4 subunit of centralspindlin in a yeast two-hybrid assay (Ban et al., 2004). It is interesting to note that in fission yeast, which does not have centralspindlin, ase1p interacts with the kinesin-6 klp9p, which itself is more closely related to MKLP2 than MKLP1 (Fu et al., 2009). Observation of animal cells that are depleted of PRC1 or of centralspindlin components indicates that their respective localisation to the central spindle is interdependent (Verbrugghe and White, 2004; Vernì et al., 2004). However, the significance of the interaction between PRC1 and centralspindlin for their recruitment to the spindle midzone and the formation of the central spindle is unclear because defects in either factor disrupt the central spindle as described in the previous sections. To answer the question of why both of these microtubule-bundling factors are needed for the formation of the central spindle, it will be crucial to generate and study ‘separation-of-function’ mutants of PRC1 and CYK4, which specifically disrupt their interaction without affecting their other functions, such as microtubule bundling.

Conclusion and future perspectives

How exactly multiple microtubule organisers cooperate to form the central spindle and the midbody remains an important and challenging question from both theoretical and technical perspectives. In vitro reconstitution assays and in silico models need to be developed and combined with live cell observation using tools to perturb the protein–protein interactions in a temporally and spatially regulated manner. These approaches will give us greater insight into the mechanisms underlying the complex network of protein machineries that drives precise cytokinesis and ensures genome stability.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Gerlich, A. Piekny and G. Correia for helpful critical comments. We apologise for unintended omissions from the interaction and localisation tables.

Footnotes

Funding

K.Y.L. and T.D. received studentships from Cancer Research UK (CRUK) and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, respectively. Research in the Mishima laboratory has been supported by funding from CRUK [grant numbers C19769/A6356, C19769/A7164 and C19769/A11985]; by core support from CRUK [grant numbers C6946/A14492]; and the Wellcome Trust [grant number 092096] to the Gurdon Institute, University of Cambridge.

Supplementary material available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/jcs.094672/-/DC1

A high-resolution version of the poster is available for downloading in the online version of this article at jcs.biologists.org. Individual poster panels are available as JPEG files at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/jcs.094672/-/DC2

References

- Abaza A., Soleilhac J. M., Westendorf J., Piel M., Crevel I., Roux A., Pirollet F. (2003). M phase phosphoprotein 1 is a human plus-end-directed kinesin-related protein required for cytokinesis. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 27844–27852 10.1074/jbc.M304522200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhmanova A., Steinmetz M. O. (2008). Tracking the ends: a dynamic protein network controls the fate of microtubule tips. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 309–322 10.1038/nrm2369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archambault V., Glover D. M. (2009). Polo-like kinases: conservation and divergence in their functions and regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 265–275 10.1038/nrm2653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaud L., Pines J., Nigg E. A. (1998). GFP tagging reveals human Polo-like kinase 1 at the kinetochore/centromere region of mitotic chromosomes. Chromosoma 107, 424–429 10.1007/s004120050326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban R., Irino Y., Fukami K., Tanaka H. (2004). Human mitotic spindle-associated protein PRC1 inhibits MgcRacGAP activity toward Cdc42 during the metaphase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 16394–16402 10.1074/jbc.M313257200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr F. A., Gruneberg U. (2007). Cytokinesis: placing and making the final cut. Cell 131, 847–860 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassi Z. I., Verbrugghe K. J., Capalbo L., Gregory S., Montembault E., Glover D. M., D’Avino P. P. (2011). Sticky/Citron kinase maintains proper RhoA localization at the cleavage site during cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 195, 595–603 10.1083/jcb.201105136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos R. N., Barr F. A. (2010). Plk1 negatively regulates Cep55 recruitment to the midbody to ensure orderly abscission. J. Cell Biol. 191, 751–760 10.1083/jcb.201008108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieling P., Telley I. A., Surrey T. (2010). A minimal midzone protein module controls formation and length of antiparallel microtubule overlaps. Cell 142, 420–432 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratman S. V., Chang F. (2007). Stabilization of overlapping microtubules by fission yeast CLASP. Dev. Cell 13, 812–827 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bringmann H., Skiniotis G., Spilker A., Kandels–Lewis S., Vernos I., Surrey T. (2004). A kinesin-like motor inhibits microtubule dynamic instability. Science 303, 1519–1522 10.1126/science.1094838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bringmann H., Cowan C. R., Kong J., Hyman A. A. (2007). LET-99, GOA-1/GPA-16, and GPR-1/2 are required for aster-positioned cytokinesis. Curr. Biol. 17, 185–191 10.1016/j.cub.2006.11.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K. D., Coulson R. M., Yen T. J., Cleveland D. W. (1994). Cyclin-like accumulation and loss of the putative kinetochore motor CENP-E results from coupling continuous synthesis with specific degradation at the end of mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 125, 1303–1312 10.1083/jcb.125.6.1303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck R. C., Tisdale J. M. (1962). The fine structure of the mid-body of the rat erythroblast. J. Cell Biol. 13, 109–115 10.1083/jcb.13.1.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballe A., Martin–Serrano J. (2011). ESCRT machinery and cytokinesis: the road to daughter cell separation. Traffic 12, 1318–1326 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01244.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai S., Weaver L. N., Ems–McClung S. C., Walczak C. E. (2010). Proper organization of microtubule minus ends is needed for midzone stability and cytokinesis. Curr. Biol. 20, 880–885 10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canman J. C., Lewellyn L., Laband K., Smerdon S. J., Desai A., Bowerman B., Oegema K. (2008). Inhibition of Rac by the GAP activity of centralspindlin is essential for cytokinesis. Science 322, 1543–1546 10.1126/science.1163086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesario J. M., Jang J. K., Redding B., Shah N., Rahman T., McKim K. S. (2006). Kinesin 6 family member Subito participates in mitotic spindle assembly and interacts with mitotic regulators. J. Cell Sci. 119, 4770–4780 10.1242/jcs.03235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalamalasetty R. B., Hümmer S., Nigg E. A., Silljé H. H. (2006). Influence of human Ect2 depletion and overexpression on cleavage furrow formation and abscission. J. Cell Sci. 119, 3008–3019 10.1242/jcs.03032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Avino P. P., Archambault V., Przewloka M. R., Zhang W., Lilley K. S., Laue E., Glover D. M. (2007). Recruitment of Polo kinase to the spindle midzone during cytokinesis requires the Feo/Klp3A complex. PLoS ONE 2, e572 10.1371/journal.pone.0000572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Avino P. P., Takeda T., Capalbo L., Zhang W., Lilley K. S., Laue E. D., Glover D. M. (2008). Interaction between Anillin and RacGAP50C connects the actomyosin contractile ring with spindle microtubules at the cell division site. J. Cell Sci. 121, 1151–1158 10.1242/jcs.026716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas M. E., Mishima M. (2010). Still entangled: assembly of the central spindle by multiple microtubule modulators. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 899–908 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas M. E., Davies T., Joseph N., Mishima M. (2010). Aurora B and 14-3-3 coordinately regulate clustering of centralspindlin during cytokinesis. Curr. Biol. 20, 927–933 10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elad N., Abramovitch S., Sabanay H., Medalia O. (2011). Microtubule organization in the final stages of cytokinesis as revealed by cryo-electron tomography. J. Cell Sci. 124, 207–215 10.1242/jcs.073486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fededa J. P., Gerlich D. W. (2012). Molecular control of animal cell cytokinesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 440–447 10.1038/ncb2482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu C., Ward J. J., Loiodice I., Velve–Casquillas G., Nedelec F. J., Tran P. T. (2009). Phospho-regulated interaction between kinesin-6 Klp9p and microtubule bundler Ase1p promotes spindle elongation. Dev. Cell 17, 257–267 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gai M., Camera P., Dema A., Bianchi F., Berto G., Scarpa E., Germena G., Di Cunto F. (2011). Citron kinase controls abscission through RhoA and anillin. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 3768–3778 10.1091/mbc.E10-12-0952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganem N. J., Storchova Z., Pellman D. (2007). Tetraploidy, aneuploidy and cancer. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 17, 157–162 10.1016/j.gde.2007.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glotzer M. (2009). The 3Ms of central spindle assembly: microtubules, motors and MAPs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 9–20 10.1038/nrm2609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin S. S., Vale R. D. (2010). Patronin regulates the microtubule network by protecting microtubule minus ends. Cell 143, 263–274 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshima G., Vale R. D. (2005). Cell cycle-dependent dynamics and regulation of mitotic kinesins in Drosophila S2 cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 3896–3907 10.1091/mbc.E05-02-0118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory S. L., Ebrahimi S., Milverton J., Jones W. M., Bejsovec A., Saint R. (2008). Cell division requires a direct link between microtubule-bound RacGAP and Anillin in the contractile ring. Curr. Biol. 18, 25–29 10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruneberg U., Neef R., Honda R., Nigg E. A., Barr F. A. (2004). Relocation of Aurora B from centromeres to the central spindle at the metaphase to anaphase transition requires MKlp2. J. Cell Biol. 166, 167–172 10.1083/jcb.200403084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruneberg U., Neef R., Li X., Chan E. H., Chalamalasetty R. B., Nigg E. A., Barr F. A. (2006). KIF14 and citron kinase act together to promote efficient cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 172, 363–372 10.1083/jcb.200511061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guizetti J., Gerlich D. W. (2010). Cytokinetic abscission in animal cells. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 909–916 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada T. (2007). Microtubule-associated proteins in higher plants. J. Plant Res. 120, 79–98 10.1007/s10265-006-0057-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hizlan D., Mishima M., Tittmann P., Gross H., Glotzer M., Hoenger A. (2006). Structural analysis of the ZEN-4/CeMKLP1 motor domain and its interaction with microtubules. J. Struct. Biol. 153, 73–84 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C. K., Coughlin M., Field C. M., Mitchison T. J. (2011). KIF4 regulates midzone length during cytokinesis. Curr. Biol. 21, 815–824 10.1016/j.cub.2011.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C. K., Coughlin M., Mitchison T. J. (2012). Midbody assembly and its regulation during cytokinesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 1024–1034 10.1091/mbc.E11-08-0721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hümmer S., Mayer T. U. (2009). Cdk1 negatively regulates midzone localization of the mitotic kinesin Mklp2 and the chromosomal passenger complex. Curr. Biol. 19, 607–612 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutterer A., Glotzer M., Mishima M. (2009). Clustering of centralspindlin is essential for its accumulation to the central spindle and the midbody. Curr. Biol. 19, 2043–2049 10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue Y. H., do Carmo Avides M., Shiraki M., Deak P., Yamaguchi M., Nishimoto Y., Matsukage A., Glover D. M. (2000). Orbit, a novel microtubule-associated protein essential for mitosis in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell Biol. 149, 153–166 10.1083/jcb.149.1.153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue Y. H., Savoian M. S., Suzuki T., Máthé E., Yamamoto M. T., Glover D. M. (2004). Mutations in orbit/mast reveal that the central spindle is comprised of two microtubule populations, those that initiate cleavage and those that propagate furrow ingression. J. Cell Biol. 166, 49–60 10.1083/jcb.200402052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jantsch–Plunger V., Gönczy P., Romano A., Schnabel H., Hamill D., Schnabel R., Hyman A. A., Glotzer M. (2000). CYK-4: A Rho family gtpase activating protein (GAP) required for central spindle formation and cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 149, 1391–1404 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W., Jimenez G., Wells N. J., Hope T. J., Wahl G. M., Hunter T., Fukunaga R. (1998). PRC1: a human mitotic spindle-associated CDK substrate protein required for cytokinesis. Mol. Cell 2, 877–885 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80302-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph N., Hutterer A., Poser I., Mishima M. (2012) ARF6 GTPase protects the post-mitotic midbody from 14-3-3-mediated disintegration. EMBO J. 31, 2604–2614 10.1038/emboj.2012.139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian M., Tollon Y., Lajoie–Mazenc I., Moisand A., Mazarguil H., Puget A., Wright M. (1993). gamma-Tubulin participates in the formation of the midbody during cytokinesis in mammalian cells. J. Cell Sci. 105, 145–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamijo K., Ohara N., Abe M., Uchimura T., Hosoya H., Lee J. S., Miki T. (2006). Dissecting the role of Rho-mediated signaling in contractile ring formation. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 43–55 10.1091/mbc.E05-06-0569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapitein L. C., Janson M. E., van den Wildenberg S. M., Hoogenraad C. C., Schmidt C. F., Peterman E. J. (2008). Microtubule-driven multimerization recruits ase1p onto overlapping microtubules. Curr. Biol. 18, 1713–1717 10.1016/j.cub.2008.09.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurasawa Y., Earnshaw W. C., Mochizuki Y., Dohmae N., Todokoro K. (2004). Essential roles of KIF4 and its binding partner PRC1 in organized central spindle midzone formation. EMBO J. 23, 3237–3248 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix B., Maddox A. S. (2012). Cytokinesis, ploidy and aneuploidy. J. Pathol. 226, 338–351 10.1002/path.3013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Mao T., Zhang Z., Yuan M. (2007). The AtMAP65-1 cross-bridge between microtubules is formed by one dimer. Plant Cell Physiol. 48, 866–874 10.1093/pcp/pcm059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Wang Z., Jiang K., Zhang L., Zhao L., Hua S., Yan F., Yang Y., Wang D., Fu C., et al. (2009). PRC1 cooperates with CLASP1 to organize central spindle plasticity in mitosis. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 23059–23071 10.1074/jbc.M109.009670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makyio H., Ohgi M., Takei T., Takahashi S., Takatsu H., Katoh Y., Hanai A., Ueda T., Kanaho Y., Xie Y., et al. (2012) Structural basis for Arf6-MKLP1 complex formation on the Flemming body responsible for cytokinesis. EMBO J. 31, 2590–2603 10.1038/emboj.2012.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matuliene J., Kuriyama R. (2002). Kinesin-like protein CHO1 is required for the formation of midbody matrix and the completion of cytokinesis in mammalian cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 1832–1845 10.1091/mbc.01-10-0504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar M., Sundareshan S., Misteli T. (2004). Human chromokinesin KIF4A functions in chromosome condensation and segregation. J. Cell Biol. 166, 613–620 10.1083/jcb.200401142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar M., Lee J. H., Sengupta K., Ried T., Rane S., Misteli T. (2006). Tumor formation via loss of a molecular motor protein. Curr. Biol. 16, 1559–1564 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh J. R., Landis S. C. (1971). The distribution of spindle microtubules during mitosis in cultured human cells. J. Cell Biol. 49, 468–497 10.1083/jcb.49.2.468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. L., Bement W. M. (2009). Regulation of cytokinesis by Rho GTPase flux. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 71–77 10.1038/ncb1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima M., Kaitna S., Glotzer M. (2002). Central spindle assembly and cytokinesis require a kinesin-like protein/RhoGAP complex with microtubule bundling activity. Dev. Cell 2, 41–54 10.1016/S1534-5807(01)00110-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima M., Pavicic V., Grüneberg U., Nigg E. A., Glotzer M. (2004). Cell cycle regulation of central spindle assembly. Nature 430, 908–913 10.1038/nature02767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollinari C., Kleman J. P., Jiang W., Schoehn G., Hunter T., Margolis R. L. (2002). PRC1 is a microtubule binding and bundling protein essential to maintain the mitotic spindle midzone. J. Cell Biol. 157, 1175–1186 10.1083/jcb.200111052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montembault E., Zhang W., Przewloka M. R., Archambault V., Sevin E. W., Laue E. D., Glover D. M., D’Avino P. P. (2010). Nessun Dorma, a novel centralspindlin partner, is required for cytokinesis in Drosophila spermatocytes. J. Cell Biol. 191, 1351–1365 10.1083/jcb.201007060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy K., Wadsworth P. (2008). Dual role for microtubules in regulating cortical contractility during cytokinesis. J. Cell Sci. 121, 2350–2359 10.1242/jcs.027052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neef R., Preisinger C., Sutcliffe J., Kopajtich R., Nigg E. A., Mayer T. U., Barr F. A. (2003). Phosphorylation of mitotic kinesin-like protein 2 by polo-like kinase 1 is required for cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 162, 863–876 10.1083/jcb.200306009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neef R., Gruneberg U., Kopajtich R., Li X., Nigg E. A., Sillje H., Barr F. A. (2007). Choice of Plk1 docking partners during mitosis and cytokinesis is controlled by the activation state of Cdk1. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 436–444 10.1038/ncb1557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neto H., Gould G. W. (2011). The regulation of abscission by multi-protein complexes. J. Cell Sci. 124, 3199–3207 10.1242/jcs.083949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura Y., Yonemura S. (2006). Centralspindlin regulates ECT2 and RhoA accumulation at the equatorial cortex during cytokinesis. J. Cell Sci. 119, 104–114 10.1242/jcs.02737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nislow C., Lombillo V. A., Kuriyama R., McIntosh J. R. (1992). A plus-end-directed motor enzyme that moves antiparallel microtubules in vitro localizes to the interzone of mitotic spindles. Nature 359, 543–547 10.1038/359543a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paramasivam M., Chang Y. J., LoTurco J. J. (2007). ASPM and citron kinase co-localize to the midbody ring during cytokinesis. Cell Cycle 6, 1605–1612 10.4161/cc.6.13.4356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavicic–Kaltenbrunner V., Mishima M., Glotzer M. (2007). Cooperative assembly of CYK-4/MgcRacGAP and ZEN-4/MKLP1 to form the centralspindlin complex. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 4992–5003 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paweletz N. (1967). Zur Funktion des “Flemming-Körpers” bei der Teilung tierischer Zellen Naturwissenschaften 54, 533–535 10.1007/BF00627210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piekny A., Werner M., Glotzer M. (2005). Cytokinesis: welcome to the Rho zone. Trends Cell Biol. 15, 651–658 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piekny A. J., Maddox A. S. (2010). The myriad roles of Anillin during cytokinesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 881–891 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruchaud S., Carmena M., Earnshaw W. C. (2007). Chromosomal passengers: conducting cell division. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 798–812 10.1038/nrm2257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagona A. P., Nezis I. P., Pedersen N. M., Liestøl K., Poulton J., Rusten T. E., Skotheim R. I., Raiborg C., Stenmark H. (2010). PtdIns(3)P controls cytokinesis through KIF13A-mediated recruitment of FYVE-CENT to the midbody. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 362–371 10.1038/ncb2036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasabe M., Machida Y. (2006). MAP65: a bridge linking a MAP kinase to microtubule turnover. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 9, 563–570 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savoian M. S., Gatt M. K., Riparbelli M. G., Callaini G., Glover D. M. (2004). Drosophila Klp67A is required for proper chromosome congression and segregation during meiosis I. J. Cell Sci. 117, 3669–3677 10.1242/jcs.01213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton W. M., McIntosh J. R. (1987). Interzone microtubule behavior in late anaphase and telophase spindles. J. Cell Biol. 105, 875–886 10.1083/jcb.105.2.875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuyler S. C., Liu J. Y., Pellman D. (2003). The molecular function of Ase1p: evidence for a MAP-dependent midzone-specific spindle matrix. J. Cell Biol. 160, 517–528 10.1083/jcb.200210021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine Y., Okada Y., Noda Y., Kondo S., Aizawa H., Takemura R., Hirokawa N. (1994). A novel microtubule-based motor protein (KIF4) for organelle transports, whose expression is regulated developmentally. J. Cell Biol. 127, 187–201 10.1083/jcb.127.1.187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severson A. F., Hamill D. R., Carter J. C., Schumacher J., Bowerman B. (2000). The aurora-related kinase AIR-2 recruits ZEN-4/CeMKLP1 to the mitotic spindle at metaphase and is required for cytokinesis. Curr. Biol. 10, 1162–1171 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00715-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu H. B., Li Z., Palacios M. J., Li Q., Joshi H. C. (1995). A transient association of gamma-tubulin at the midbody is required for the completion of cytokinesis during the mammalian cell division. J. Cell Sci. 108, 2955–2962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon G. C., Schonteich E., Wu C. C., Piekny A., Ekiert D., Yu X., Gould G. W., Glotzer M., Prekeris R. (2008). Sequential Cyk-4 binding to ECT2 and FIP3 regulates cleavage furrow ingression and abscission during cytokinesis. EMBO J. 27, 1791–1803 10.1038/emboj.2008.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slep K. C. (2009). The role of TOG domains in microtubule plus end dynamics. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37, 1002–1006 10.1042/BST0371002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers W. G., Saint R. (2003). A RhoGEF and Rho family GTPase-activating protein complex links the contractile ring to cortical microtubules at the onset of cytokinesis. Dev. Cell 4, 29–39 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00402-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian R., Wilson–Kubalek E. M., Arthur C. P., Bick M. J., Campbell E. A., Darst S. A., Milligan R. A., Kapoor T. M. (2010). Insights into antiparallel microtubule crosslinking by PRC1, a conserved nonmotor microtubule binding protein. Cell 142, 433–443 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara R., Goshima G. (2010). Functional central spindle assembly requires de novo microtubule generation in the interchromosomal region during anaphase. J. Cell Biol. 191, 259–267 10.1083/jcb.201004150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara R., Nozawa R. S., Tomioka A., Petry S., Vale R. D., Obuse C., Goshima G. (2009). The augmin complex plays a critical role in spindle microtubule generation for mitotic progression and cytokinesis in human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 6998–7003 10.1073/pnas.0901587106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unno K., Hanada T., Chishti A. H. (2008). Functional involvement of human discs large tumor suppressor in cytokinesis. Exp. Cell Res. 314, 3118–3129 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.07.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugghe K. J., White J. G. (2004). SPD-1 is required for the formation of the spindle midzone but is not essential for the completion of cytokinesis in C. elegans embryos. Curr. Biol. 14, 1755–1760 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernì F., Somma M. P., Gunsalus K. C., Bonaccorsi S., Belloni G., Goldberg M. L., Gatti M. (2004). Feo, the Drosophila homolog of PRC1, is required for central-spindle formation and cytokinesis. Curr. Biol. 14, 1569–1575 10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Dassow G., Verbrugghe K. J., Miller A. L., Sider J. R., Bement W. M. (2009). Action at a distance during cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 187, 831–845 10.1083/jcb.200907090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walczak C. E. (2005). CLASP fluxes its mitotic muscles. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 5–7 10.1038/ncb0105-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. Z., Adler R. (1995). Chromokinesin: a DNA-binding, kinesin-like nuclear protein. J. Cell Biol. 128, 761–768 10.1083/jcb.128.5.761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B. C., Riedy M. F., Williams E. V., Gatti M., Goldberg M. L. (1995). The Drosophila kinesin-like protein KLP3A is a midbody component required for central spindle assembly and initiation of cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 129, 709–723 10.1083/jcb.129.3.709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T., Hikida M., Kurosaki T. (2006). Regulation of cytokinesis by mgcRacGAP in B lymphocytes is independent of GAP activity. Exp. Cell Res. 312, 3517–3525 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yüce O., Piekny A., Glotzer M. (2005). An ECT2-centralspindlin complex regulates the localization and function of RhoA. J. Cell Biol. 170, 571–582 10.1083/jcb.200501097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavortink M., Contreras N., Addy T., Bejsovec A., Saint R. (2005). Tum/RacGAP50C provides a critical link between anaphase microtubules and the assembly of the contractile ring in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell Sci. 118, 5381–5392 10.1242/jcs.02652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W. M., Fang G. (2005). MgcRacGAP controls the assembly of the contractile ring and the initiation of cytokinesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 13158–13163 10.1073/pnas.0504145102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W. M., Seki A., Fang G. (2006). Cep55, a microtubule-bundling protein, associates with centralspindlin to control the midbody integrity and cell abscission during cytokinesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 3881–3896 10.1091/mbc.E06-01-0015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C., Jiang W. (2005). Cell cycle-dependent translocation of PRC1 on the spindle by Kif4 is essential for midzone formation and cytokinesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 343–348 10.1073/pnas.0408438102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C., Lau E., Schwarzenbacher R., Bossy–Wetzel E., Jiang W. (2006). Spatiotemporal control of spindle midzone formation by PRC1 in human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 6196–6201 10.1073/pnas.0506926103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.