Abstract

Patients with hematologic malignancies often require urgent, aggressive, and lengthy chemotherapy treatment. These treatment regimens, divided into cycles, result in extended, often isolating periods of hospitalization where any direct clinical benefit for the patient, such as remission or “no evidence of disease” is not immediately declared. Consequently, this population is at a high risk of experiencing severe levels of cancer related distress. Cancer related distress is a complex psychosocial phenomenon that has consequences for patients, their families as well as the healthcare staff. Thus the importance of prevention, early recognition, treatment and management is unquestionable. Nurses have an important role to help identify and manage the presence of cancer related distress in these patients, as well as their family’s. Nurses should work proactively in close partnership with an interdisciplinary team to effectively provide the necessary support for patients experiencing or who are at risk for high levels of cancer related distress. This case study and subsequent discussion illustrates the symptom management needs and challenges related to cancer related distress in the patient with a hematologic malignancy. Current evidence-based practice guidelines for the assessment and management of cancer related distress will be presented.

Keywords: distress, symptom management, clinical management, hematologic malignancy

Introduction

Approximately 140,310 people were diagnosed with a hematological malignancy (HM) (leukemia, lymphoma, and myeloma) in 2011.1 The treatment for this group of diseases is unique and often includes regimens that are long, aggressive, require extended periods of hospitalization and may include high-dose chemotherapy and possibly hematopoietic stem cell transplant.2 Improvements in chemotherapy treatment have resulted in prolonged survival. However, depending on a patients diagnosis and chromosomal abnormalities, the 5-year survival rate may be as low as 21%3 and include numerous associated physical and/or psychological symptoms that are a result of the treatment and/or the disease process. Given the intense treatments and symptoms found in this population it is not surprising that they also suffer from high levels of cancer-related distress.4 Specifically cancer-related distress has been found to occur in as many as 48.7% of patients with a HM.5

Cancer-related distress is defined by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) as: “a multifactorial unpleasant emotional experience of a psychological (cognitive, behavioral, emotional), social and/or spiritual nature that may interfere with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its physical symptoms and its treatment…”6 While cancer-related distress is often amenable to treatment it is frequently under diagnosed and thus undertreated in patients receiving care for cancer.7–8 However, when cancer-related distress remains unrecognized and/or under treated by healthcare professionals it may lead to such negative consequences as: impaired decision-making, decreased satisfaction with healthcare received,9 as well as impact on treatment and patient recovery.10 Patients with high levels of cancer-related distress may become disabled with depression, anxiety, isolation, panic and existential and spiritual crisis.6 Prompt diagnosis and management of cancer-related distress can result in improved communication, and decreased healthcare utilization.6 Thus, the identification and management of cancer-related distress is pertinent for nurses practicing in oncology, palliative care and hospice settings and particularly true for patients with a HM.

Case Presentation

Martin is a 54-year old husband and father of three, who lives in a rural area, has worked at the same factory since graduating from high school. He has one child in college and the youngest child is a junior in high school. His wife works as an administrative assistant at the local school. Martin presented to a community hospital with uncontrolled epistaxis. After initial medical work-up he was told that he likely had acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and was transferred to an academic medical center several hours away. The diagnosis of AML was confirmed and he promptly started induction chemotherapy.

The health care team, including the doctors, nurses, and social work have all spoken to Martin regarding the acuity of the disease process as well as the course of treatment. Martin understands that he will likely spend at least the next four weeks in the hospital for chemotherapy and subsequent recovery from the treatment. He will then need to come into the hospital for additional consolidation treatment to ensure that the leukemia will not relapse. Martin’s wife, who has now been at home alone for several weeks is concerned about financial stability. She has suggested that he start to consider the possibility of long-term work disability. Martin refuses to discuss this option and continues to insist he just wants to get through this treatment and resume his life. He feels tremendous financial and personal pressure to provide for his family, including college tuition and maintaining their home. He believes he is going to die and is worried that he will leave his family without adequate support. He does not want to trouble his wife or children and has no outlet for his concerns.

Martin’s family tries to come regularly to see him but these visits are limited to the weekends due to distance. He appears to distance himself from his family, expressing little emotion. Martin spends the majority of his time in his room with the blinds drawn. He is reluctant to get out of bed due to fatigue, pain from mucositis and intermittent diarrhea. He is polite but quiet with the nursing staff and asks no questions of the medical team on daily rounds. He is considered to be an “easy” patient and while medications are prescribed for diarrhea and mucositis pain, the assessment of psychosocial needs is never considered.

Assessment of Cancer Related Distress

In 1998, the NCCN, through an interdisciplinary panel initiated the development of clinical practice guidelines focused on the psychosocial care of patients with cancer.6,10 Since then, recommendations regarding the detection and management of cancer related distress has been recognized as an important aspect of clinical cancer care.10 While the NCCN guidelines were designed for the assessment and management of cancer related distress in community oncology practice,6 the basic principles are also appropriate and applicable to inpatient hematology/oncology care.

Specifically, the NCCN recommends assessing patient’s level of cancer related distress during the clinic visit prior to their appointment.6 However, for patients with a HM who are often immediately hospitalized for supportive management while confirmatory diagnosis is made and subsequent treatment is initiated, modifications in screening are necessary. Thus, screening for cancer related distress in this unique population should be initiated at time of hospital admission, at patient directed time intervals and during transitions in the treatment process, or when a patient experiences adverse events, such as infection. The optimal timing of screening after the initial hospitalized assessment is still under investigation.7 A reasonable starting point for clinical practice could be once a week for those patients found to have high levels of distress at their initial admission screening. Important to note is the fact that patients with a HM where cure is the focus receive far less palliative care referrals when compared to patients receiving medical oncology/ solid tumor care.4,12

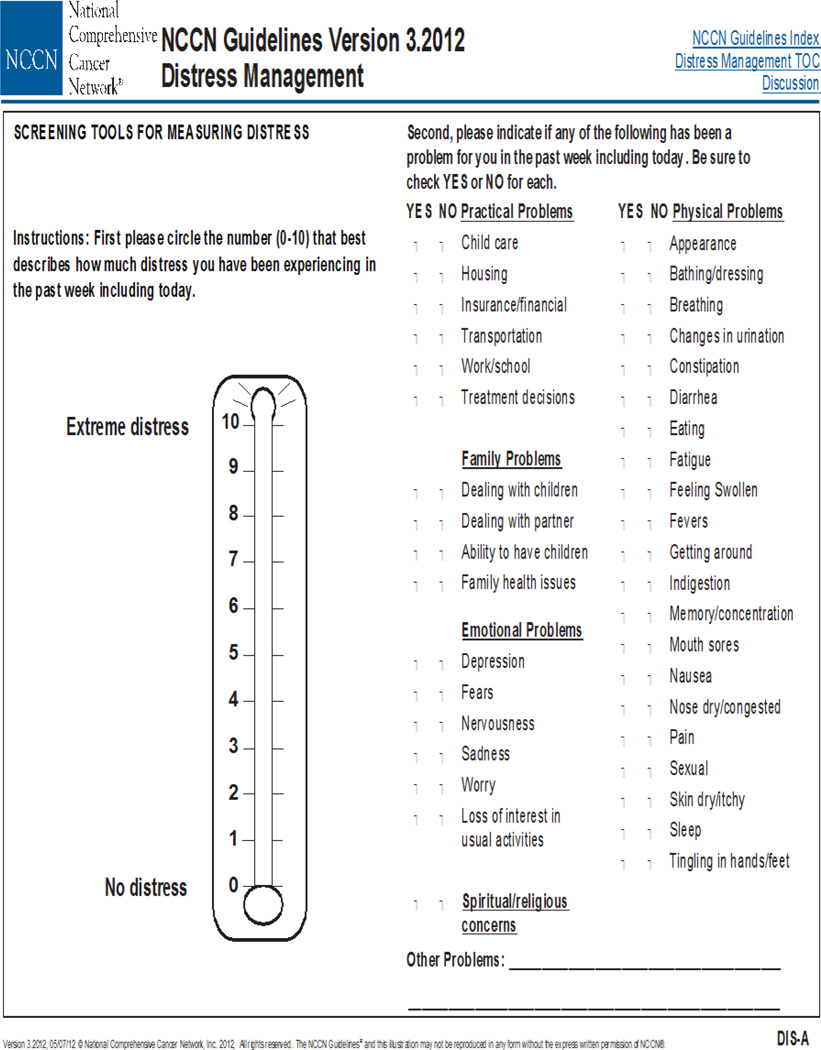

The NCCN Distress Thermometer (DT), (figure 1) is the recommended instrument for the assessment of cancer related distress, as it has been found to be both rapid and effective for the measurement of cancer-related distress.13 The DT has been validated with the Hospital Anxiety and Depressive Scale (HADs)14 and the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D)15 Additionally, the DT has been found to more accurately identify the presence of cancer-related distress, when compared to such instruments as the (HADs).14 The DT includes both a single-item likert scale of cancer related distress on a 0–10 scale, as well as the assessment of five unique causal domains of cancer related distress for patients. These five domains include: practical problems (housing, insurance, transportation); family problems; emotional problems; spiritual/religious concerns; and/or physical problems. Patients are asked to indicate with yes/no, if specific issues from each of the five domains have been a problem in the past week. The DT has also been validated as a useful measure in the screening for cancer related distress in patients hospitalized for bone marrow stem cell transplantation.15

Figure 1. Distress Thermometer.

Reproduced with permission from the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Distress Management (V.3.2012). © 2012 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. Available at: NCCN.org. Accessed [May 02, 2012]. To view the most recent and complete version of the NCCN Guidelines®, go on-line to NCCN.org.

The inherent nature of cancer-related distress may effect any domain of a patients life, including: physical, psychological, social and/or spiritual. Table 1 details the four domains of distress across the disease trajectory for patients with a HM. These patients may experience physical and/or psychological symptoms at any point in the disease process. Important to note is that patients who report physical symptoms are less likely to have their psychological symptoms, including cancer related distress diagnosed and subsequently managed.10 The presentation of physical symptoms that are actually the result of psychological symptoms is the somatization of symptoms, where physical symptoms present as a result of psychological cancer related distress.10 The recognition and treatment of somatic symptoms is complex and have been found to increase the need for healthcare utilization.16

Table 1.

Distress Across the Hematologic Malignancy Disease Trajectory *

| Distress Domain |

Hospitalization | Transplant | Ambulatory | End of Treatment | End of Life |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical |

|

||||

| Psychological | Psych Symptoms4,6,17:

|

Psych Symptoms6,15:

|

Psych Symptoms4,6:

|

Psych Symptoms4, 6:

|

Psych Symptoms6:

|

| Social | |||||

| Spiritual | Religion/Spiritual17 |

Note that the research is still developing in the area of distress across the disease trajectory and within each domain of distress for patients with a hematologic malignancy. Thus, some of the content presented are proposals by the authors for clinical consideration based on NCCN guidelines for when and how distress may present, but may not be relevant to each patients disease trajectory. However, this requires further research.

Commonly reported symptoms of cancer related distress include: anger, sadness, insomnia, anorexia, and social isolation.6 Somatic symptoms commonly found in distressed patients include: gastrointestinal upset (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), pain (headaches, neck/shoulder pain, parathesia), fatigue, weakness, dyspnea, and/or palpitations.16 A detailed list of physical symptoms commonly found to be present in patients reporting cancer related distress is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

| General |

| Anger, feeling out of control |

| Anxiety |

| Depression |

| Difficulty making decisions |

| Feelings of hopelessness |

| Feeling overcome by sense of dread |

| Feelings of being overwhelmed |

| Inability to cope with pain, tiredness, and nausea |

| Panic |

| Poor sleep |

| Poor appetite |

| Poor concentration |

| Preoccupation with thoughts of illness and death |

| Sadness |

| Social isolation |

| Uncertainty |

| Vulnerability |

| Worry |

| Somatic |

| Gastrointestinal upset |

| Nausea |

| Vomiting |

| Diarrhea |

| Pain |

| Headache |

| Neck/Shoulder pain |

| Parathesia |

| Fatigue |

| Weakness |

| Dyspnea |

| Palpitations |

Patients with a HM may also experience social distress as a result of their diagnosis and treatment. Social distress may be provoked by a sense of social isolation as well as financial strains that may develop as a result of long hospitalizations given that these patients may spend weeks to months hospitalized, often in a medical center hours from their home and main support system. After discharge these patients are typically neutropenic and thus at high risk for infection related complications. Thus, the social distress may extend to times when while they are home may still need to limit contact with family and friends, especially young children or grandchildren.

Spiritual distress may develop at any time point in the disease trajectory for these patients. Distress in this domain may be generated by feelings of guilt, burden, loss, to place meaning on their illness, as well as their relationships and/or beliefs in a higher power. The NCCN Distress Guidelines provide extensive suggestions for the assessment and care of patients experiencing spiritual distress.

Mild cancer related distress (a score of 4 or less on the DT) is considered an expected and acceptable level of cancer related distress for patients given their current situation. Typical symptoms associated with this level of cancer related distress may be such feelings as fear, worry and uncertainty regarding the future. The symptoms associated with cancer related distress may be present at any point in the disease trajectory.6

Moderate to severe cancer related distress is considered for any whose score is greater than 4 on the DT. Common symptoms associated with this level of cancer-related distress include: excessive worries, fears, sadness, unclear thinking, despair, hopelessness.6 Understanding and recognizing individuals who are increased risk for developing high levels of cancer related distress is an important aspect in the screening and assessment of patients. There are several risk factors that place an individual at increased risk for developing high levels of cancer related distress. Table 3 provides a specific examples of these risk factors, including: cognitive impairment, communication barriers, presence of significant comorbid conditions, history of psychiatric illnesses as well as social stressors.6 Table 4 presents unique factors found to increase an individual’s susceptibility to cancer related distress.

Table 3.

| Cognitive Impairment |

| Communication Barriers |

| Language |

| Literacy |

| Physical |

| Comorbid Diseases |

| History of Psychiatric Illness |

| Depression |

| Substance abuse |

| Suicide attempt |

| Social Issues |

| Dependent children |

| Family conflicts |

| Female |

| Financial problems |

| Inadequate social support |

| History of abuse |

| Lives alone |

| Younger age |

| Spiritual/religious concerns |

| Uncontrolled symptoms |

Table 4.

| Concerning symptom |

| Time of diagnosis |

| Diagnostic testing |

| Pre-treatment |

| Treatment |

| Pre |

| Modification in |

| Post |

| Hospital discharge |

| Follow-up and surveillance |

| Disease recurrence |

| Advanced staged cancer |

| End of life |

| Someone close to patient died of cancer |

| Someone close to patient recently had a serious illness or death |

While the use of the DT for the assessment of cancer related distress offers fast and reliable results, clinicians should not rely solely on this instrument alone for screening. Imperative to appropriate assessment is the use of active listening through both verbal and nonverbal behaviors.10 During active listening not only is the clinician reinforcing empathy for the patient by creating an empathetic environment, they are also making it possible to better assess the current state of the patient.10 Additionally, Ryan and colleagues (2005) report that when clinicians acknowledge the presence of cancer related distress of a patient, the patient is then more likely to provide further information related to their etiology of their distress. This empathic exchange further enhances the clinician’s understanding of the origin of cancer related distress for the patient.

Management of Cancer-Related Distress

Recommendations on the management of patients with cancer related distress vary depending on the level of distress that the patient reports, as well as the symptoms that they are experiencing. Patients who report mild cancer-related distress are typically managed by the primary healthcare team, which includes the nurses and oncologists. In caring for patients with mild cancer-related distress it is crucial for the healthcare providers to develop a strong communication style which facilitates a trusting relationship.6 This communication should include ample time for patients to ask questions.10 Teaching relaxation techniques to manage associated symptoms is another supportive care measure that nurses can facilitate for the management of mild cancer-related distress for patients. Providing patients with a list of community resources, support groups, online resources, as well as reinforcing to the patient that their feelings are quite normal may help manage the levels of cancer-related distress. The regular re-evaluation of distressing symptoms should be routine across the disease treatment trajectory.

The NCCN recommends that any patient with moderate to severe distress should receive a referral for further evaluation by either mental health professional, social worker, counseling or spiritual counselor as appropriate. In order to be truly proactive for patients with HM, those identified as “high risk” for cancer-related distress at diagnosis and admission to the hospital should have immediate and consistent Palliative Care, Social Work and/or Clinical Psychology consulted on a proactive basis.

The patient reported domain found to be causing the cancer-related distress from the DT should guide the specific referral. Mental health services are completed by either a psychologist or psychiatrist and include further diagnostic assessment of the cancer related distress as well as further exploring areas such as symptoms and past psychiatric history. The NCCN panel has developed specific cancer-related distress guidelines for the management of the seven most common psychiatric disorders, which include: dementia, delirium, mood disorder, adjustment disorder, anxiety disorder, substance-abuse, and personality disorders.6

For patients whose cancer-related distress is a result of psychosocial problems such as adjustment to illness, social isolation, quality of life issues, and/or decision-making, counseling and psychotherapy are recommended.6 For these patients the nurse can be instrumental in providing supportive care during the counseling process, as well as assisting the patient to identify community resources. Providing the patient with information on national resources such as the American Cancer Society, American Psychosocial Oncology Society and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, may also be beneficial for patients. The nurse of course will continue to provide education to the patient and family and advocate for optimal symptom and pain reeducation interventions.

Religion and spirituality are important aspects of many people’s lives. This is especially true at times of illness, where many people report using religion or spiritual resources as a method to cope with their illness.6 Therefore when religious or spiritual distress arises, such as loss of faith, relating to God or a higher power, a high level of distress may also develop. Patients, may feel comfortable speaking with the nurse about some of these spiritual concerns, however when high levels of distress are present the patient receives a visit from a chaplain. Thus, a chaplain is an indispensable member of the interdisciplinary team.

Case Study Conclusion

Martin is day 18 post-induction chemotherapy treatment and his mucositis pain continues while his diarrhea has become more frequent. He has also begun to develop a dull headache, which he tells his nurse during his morning assessment. Given that Martin’s platelet count is 25,000 per microliter a stat computed tomography (CT) is ordered. When Martin learns from his nurse that he will need to have to leave the unit for a CT he confides in the nurse “I just don’t think I can take anything else”. In hearing this, the nurse sits down and talks with Martin about how he is feeling. The nurse actively listens as Martin confides how scared he is about his future. The nurse recognizes that Martin appears to be distressed. The nurse discusses this assessment with the healthcare team and a palliative care consultation is made.

The palliative care team visits with Martin the next day and finds that he is very worried and nervous about his future as well as that of his family. He confides that he is having a hard time being away from home, not being able to work, and constantly worrying about what his lab counts are. The team determines that Martin is suffering from severe emotional cancer-related distress. The palliative care team teaches Martin relaxation techniques and initiates a counseling referral. Now that the emotion of distress has been identified the healthcare team is more directly asking Martin how he is doing and providing more time for questions. By the end of the week, Martin’s headache has subsided and his diarrhea is minimal.

Martin’s future is uncertain at this point. Once he is well enough to go home, Martin will be closely monitored. Future bone marrow biopsies will determine whether Martin’s cancer responded to the initial therapies. If the biopsy findings show he did respond then Martin will begin consolidation chemotherapy treatment, which requires another 5-days of hospitalized treatment. However, if Martins cancer did not respond to the treatment he will need to be hospitalized for re-induction chemotherapy treatment. Additionally, depending on Martin’s response he may be a candidate for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Regardless of the treatment course, many of these patients often can benefit from the support of palliative care service.4,12

Implications for Nursing

Cancer-related distress is a common symptom experienced by patients to varying degrees across the cancer disease trajectory. Unfortunately, cancer-related distress is commonly under-recognized and subsequently undertreated.7,8,17 This is especially true for patients with a HM who are highly susceptible to moderate to severe levels of cancer-related distress, given the typical disease course (extended periods of hospitalization, high risk of treatment failure and/or disease recurrence) all of which may strain social issues for patients and their families. Thus, oncology, palliative care and hospice nurses all play a vital role in the assessment and management of cancer-related distress for this unique patient population. Nurse practitioners can identify and initiate appropriate referrals for consultations per the cancer-related distress management algorithm developed by the NCCN. Nurses who care for patients on a day-to-day basis establish relationships and thus have the advantage of being able to assess changes in levels of patient distress as well as the ability to facilitate important communication necessary for the best distress management over the course of treatment.18 In order to most appropriately manage cancer related distress there needs to be standards of assessment universally incorporated into clinical practice, staff need to be aware of the symptoms, how to empathetically communicate with patients, as well as how to identify what interventions are best suited for patients given their identified source(s) of cancer related distress.18 Further research is needed in distress and the psychosocial support needs of patients with a HM.19

Cancer-related distress is highly prevalent and often unrecognized in patients. Yet, the presence of distress may have many etiologies and manifest as additional physical symptoms, which only further exacerbates the discomfort and suffering these patient experience.10,16 Thus, the assessment and early diagnosis of distress is imperative to the appropriate management. Oncology, palliative care and hospice nurses should work proactively in close partnership with an interdisciplinary team to effectively screen and support patients at high risk for cancer related distress such those receiving treatment for a HM.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Tara A. Albrecht, Interdisciplinary Training of Nurse Scientists in Cancer Survivorship Research (T32NR011972), University of Pittsburgh, School of Nursing, Pittsburgh, PA.

Margaret Rosenzweig, University of Pittsburgh, School of Nursing, Pittsburgh, PA.

References

- 1.Horner MJ, Ries LAG, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2006. 2009 Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006/.

- 2.McGrath P. Qualitative findings on the experience of end-of-life care for hematological malignancies. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine. 2002;19(2):103–111. doi: 10.1177/104990910201900208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pulte D, Gondos A, Brenner H. Expected long-term survival of patients diagnosed with acute myeloblastic leukemia during 2006–2010. Annals of Oncology. 2010;21(2):335–341. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manitta V, Zordan R, Cole-Sinclair M, Nandurkar H, Philip J. The symptom burden of patients with hematological malignancy: A cross-sectional observational study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2011;42(3):432–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson LE, Angen M, Cullum J, et al. High levels of untreated distress and fatigue in cancer patients. British Journal of Cancer. 2004;90(12):2297–2304. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Network NCC. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Distress Management. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bidstrup PE, Johansen C, Mitchell AJ. Screening for cancer-related distress: Summary of evidence from tools to programmes. Acta Oncologica (Stockholm, Sweden) 2011;50(2):194–204. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.533192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ziegler L, Hill K, Neilly L, et al. Identifying psychological distress at key stages of the cancer illness trajectory: A systematic review of validated self-report measures. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 2011;41(3):619–636. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holland J. Update: NCCN practice guidelines for the management of psychosocial distress. Oncology. 1999;13(11A):459–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryan H, Schofield P, Cockburn J, et al. How to recognize and manage psychological distress in cancer patients. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2005;14(1):7–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2005.00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murillo M, Holland J. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of psychosocial distress at end of life. Palliative and Supportive Care. 2004;2:65–77. doi: 10.1017/s1478951504040088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howell DA, Shellens R, Roman E, et al. Haematological malignancy: are patients appropriately referred for specialist palliative and hospice care? A systematic review and meta-analysis of published data. Palliative Medicine. 2011;25(6):630–641. doi: 10.1177/0269216310391692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffman B, Zevon M, D’Arrigo M, Cecchini T. Screening for distress in cancer patients: The NCCN rapid-screening measure. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13:792–799. doi: 10.1002/pon.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akizuki N, Yamawaki S, Akechi T, Nakano T, Uchitomi Y. Development of an impact thermometer for use in combination with the distress thermometer as a brief screening tool for adjustment disorders and/or major depression in cancer patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2005;29:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ransom S, Jacobsen PB, Booth-Jones M. Validation of the Distress Thermometer with bone marrow transplant patients. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15(7):604–612. doi: 10.1002/pon.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simon G, Gater R, Kisely S, Piccinelli M. Somatic Symptoms of Distress: An International Primary Care Study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1996;58:481–488. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199609000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SJ, Katona LJ, De Bono SE, Lewis KL. Routine screening for psychological distress on an Australian inpatient haematology and oncology ward: impact on use of psychosocial services. The Medical Journal of Australia. 2010;193(5 Suppl):S74–S78. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ridner S. Psychological distress: Concept analysis. Journal of advanced nursing. 2004;45(5):536–545. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paul CL, Sanson-Fisher R, Douglas HE, et al. Cutting the research pie: a value-weighting approach to explore perceptions about psychosocial research priorities for adults with haematological cancers. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2011;20(3):345–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2010.01188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]