Abstract

Mixed-linkage (1→3),(1→4)-β-d-glucan is a plant cell wall polysaccharide composed of cellotriosyl and cellotetraosyl units, with decreasingly smaller amounts of cellopentosyl, cellohexosyl, and higher cellodextrin units, each connected by single (1→3)-β-linkages. (1→3),(1→4)-β-Glucan is synthesized in vitro with isolated maize (Zea mays) Golgi membranes and UDP-[14C]d-glucose. The (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase is sensitive to proteinase K digestion, indicating that part of the catalytic domain is exposed to the cytoplasmic face of the Golgi membrane. The detergent {3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonic acid} (CHAPS) also lowers (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase activity. In each instance, the treatments selectively inhibit formation of the cellotriosyl units, whereas synthesis of the cellotetraosyl units is essentially unaffected. Synthesis of the cellotriosyl units is recovered when a CHAPS-soluble factor is permitted to associate with Golgi membranes at synthesis-enhancing CHAPS concentrations but lost if the CHAPS-soluble fraction is replaced by fresh CHAPS buffer. In contrast to other known Golgi-associated synthases, (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase behaves as a topologic equivalent of cellulose synthase, where the substrate UDP-glucose is consumed at the cytosolic side of the Golgi membrane, and the glucan product is extruded through the membrane into the lumen. We propose that a cellulose synthase-like core catalytic domain of the (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase synthesizes cellotetraosyl units and higher even-numbered oligomeric units and that a separate glycosyl transferase, sensitive to proteinase digestion and detergent extraction, associates with it to add the glucosyl residues that complete the cellotriosyl and higher odd-numbered units, and this association is necessary to drive polymer elongation.

Mixed-linkage (1→3),(1→4)-β-d-glucans are plant cell wall polysaccharides that, among flowering plants, are found only in grasses and cereals and related members of the Poales (Smith and Harris, 1999). Their architectural role in the wall is to form a tight coating on cellulose microfibrils, where they may interact with other cellulose cross-linking glycans during growth (Carpita et al., 2001). (1→3),(1→4)-β-Glucans are synthesized and secreted during cell elongation and are largely degraded when elongation stops. They are also synthesized in the walls of the endosperm of the caryopses and maternal tissues surrounding them (Fincher, 1992).

(1→3),(1→4)-β-Glucans are unbranched Glc polymers composed primarily of cellotriosyl and cellotetraosyl units that are separated by single (1→3)-β-linkages (Staudte et al., 1983). Higher order cellodextrin units up to DP 15 are observed in decreasing abundance but with the odd-numbered cellodextrin unit about twice as abundant as the next higher even-numbered unit (Wood et al., 1994). The molar ratio of cellotriosyl to cellotetraosyl units is about 3:1 for walls of elongating tissues and endosperm walls of cereal grains (Wood et al., 1994; Carpita, 1996). The glucan can be synthesized in vitro from enriched Golgi membrane fractions with UDP-Glc as a substrate (Gibeaut and Carpita, 1993). At substrate concentrations between 100 and 250 μm UDP-Glc, the β-glucans synthesized in vitro are similar in size and in ratio of cellotriosyl and cellotetraosyl units to that synthesized in vivo, whereas at limited substrate less than 10 μm, fewer cellotriosyl units are made in vitro (Buckeridge et al., 1999). In contrast, (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucans synthesized at high substrate concentration nearing saturation are almost entirely cellotriosyl units, and the next higher odd-numbered cellopentaosyl units become twice as abundant as the cellotetraosyl units (Buckeridge et al., 1999, 2001).

Because (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan and cellulose are composed of unbranched cellodextrin structures and because of several common features of their synthesis, we proposed that (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase is more closely related to cellulose synthase than are synthases of other non-cellulosic plant β-glycans (Gibeaut and Carpita, 1993, 1994a, 1996; Buckeridge et al., 1999, 2001). If the mechanism of (1→4)-β-d-glucan synthesis in cellulose involves two glycosyl-transferase activities operating in concert to add cellobiosyl units to the growing polymer (Carpita and Vergara, 1998), then (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthesis involves three distinct glucosyl transferase activities to make cellotriosyl instead of cellobiosyl units (Buckeridge et al., 2001). Because of the constraints on steric configuration imposed by the synthase complex, cellobiosyl units in a cellulose synthase would be linked to the O-4 of the non-reducing terminal Glc of an acceptor chain, whereas linkage of a cellotriosyl or odd-numbered cellodextrin unit would occur at the O-3 of the non-reducing terminal sugar, resulting in splicing of the units by single (1→3)-β-linkages (Buckeridge et al., 2001). Disruption of the Golgi membranes with detergents or collapse of the pH gradient across sealed membranes by protonophores results in stimulation of callose synthesis (Gibeaut and Carpita, 1993). A Golgi-associated callose synthesis under these conditions is found only in maize (Zea mays) and is thought to arise as a “default” activity of the disrupted (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase (Gibeaut and Carpita, 1993, 1994a).

The topologic orientation of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase complex with respect to the Golgi membrane has not been defined experimentally. Recently, we have shown that limited proteolysis of intact Golgi membranes activates callose synthesis while greatly diminishing (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthesis (Urbanowicz et al., 2002). This suggests that at least part of the synthase complex is located on the cytosolic face of the Golgi. Circumstantial evidence for a topologic orientation toward the cytosol for (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase is provided by the finding that in maize Suc synthase (SuSy) is detected immunocytochemically at the Golgi membranes and plasma membrane, whereas in soybean (Glycine max), the synthase is only detected in plasma membranes (Buckeridge et al., 1999). Amor et al. (1995) reported that SuSy from cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) fibers is tightly associated with cellulose synthase at the plasma membrane, where the enzyme may serve to channel the UDP-Glc from Suc degradation at the cytoplasmic side of the membrane to cellulose synthase. An association of SuSy with the Golgi membranes of a cereal species indicates that such a metabolic channeling may occur in vivo for (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase as well (Buckeridge et al., 1999).

We report here that limited proteolysis and neutral detergent treatments with CHAPS below the critical micellar concentration (CMC) each markedly decrease the synthesis of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan. However, the inhibition at the lowest effective treatments specifically decreases the number of cellotriosyl units and not the cellotetraosyl units. Synthase reactions at low substrate concentrations show that the even-numbered units of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan are made by a separate mechanism from that of odd-numbered cellodextrin units. These findings support a model in which (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase is the topologic equivalent of cellulose synthase but that a separate glycosyl transferase, sensitive to proteinase and extractable with detergent, associates with a core synthase to produce the cellotriosyl units that form most of the native polymer. When the putative glycosyl transferase is removed by proteolysis or detergent, the core synthase is still capable of making polymers of mostly cellotetraosyl units but of much smaller molecular mass. However, synthesis of cellotriosyl units is recovered when a CHAPS-soluble factor is diluted to permissive concentration but not when the CHAPS-soluble fraction is replaced with fresh reaction buffer (RB) with 250 μm UDP-Glc. Although the core synthase may be encoded by a member of the CESA/CSL gene superfamily (Vergara and Carpita, 2001), the search for other catalytic components associated with a core synthase must now be widened.

RESULTS

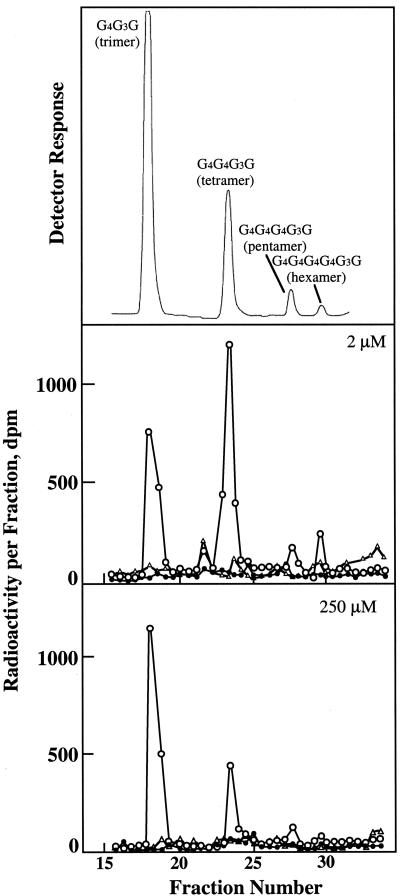

Limited Proteolysis Selectively Lowers Synthesis of Cellotriose Units

Endohydrolase digestion of the (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan product from synthase reactions in vitro produced the diagnostic cellodextrin-(1→3)-d-Glc oligomers from authentic (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan (Fig. 1). Much smaller amounts of cellopentaosyl and cellohexaosyl units were observed but were quantified only in kinetic experiments at low substrate concentrations. None of the four cellodextrin-(1→3)-d-Glc oligomers were observed in boiled controls or in the absence of endohydrolase digestion. Two additional peaks of radioactivity resolved from these oligomers appear independently from endohydrolase action only with active enzyme preparations (Fig. 1). In earlier experiments, we found that they are greatly decreased upon treatment of the membranes with activated charcoal and are suspected of being glucosylated flavonoids (Gibeaut and Carpita, 1993). Some higher oligomers are observed in the undigested 2 μm reaction products that may represent dimers and trimers of cellodextrin-(1→3)-Glc synthesized in vitro, which are resolved by HPAEC without digestion.

Figure 1.

Quantitation of radiolabeled cellodextrin-(1→3)-d-Glc oligomers of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography (HPAEC) and liquid scintillation spectroscopy. Upper trace, Profile of cellodextrin-(1→3)-d-Glc oligomers as detected by pulsed amperometry. G4G3G, Cellobiosyl-(1→3)-d-Glc, and so forth. The abundance of the G4G3G oligomer implies the abundance of the cellotriose unit and so forth. Lower traces, Examples of the distribution of radioactivity in the cellodextrin-(1→3)-β-d-Glc oligomers formed in the presence of 2 and 250 μm UDP-Glc (○) in RB supplemented with 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS. Boiled enzyme preparations (•) and reaction products undigested with endo-β-glucanase (▵) were run as controls. Radioactivity is detected by liquid scintillation spectroscopy in 0.5-mL fractions from the column. The molar equivalent amounts of units synthesized were calculated by dividing the total radioactivity recovered by the number of glucosyl residues in the oligomer. No radioactivity is associated with these peaks in the absence of Bacillus subtilis endohydrolase treatment.

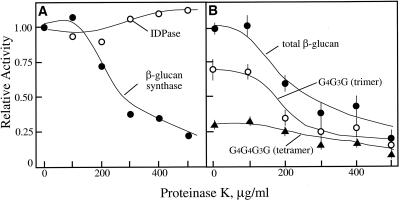

(1→3),(1→4)-β-Glucan with a cellotriosyl to cellotetraosyl molar ratio similar to that observed in vivo was obtained in vitro at 250 μm UDP-Glc. Pretreatments of Golgi membranes with increasing amounts of proteinase K did not affect the activity of IDPase, a marker enzyme known to reside with the lumen of the Golgi membranes (Morré and Buckout, 1977), whereas (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase was sensitive (Fig. 2A). The proteinase K selectively lowered the amount of cellotriosyl units produced in vitro without significant alteration in the amount of cellotetraosyl units (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Relative activities of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase and IDPase upon treatment with proteinase K. A, Molar equivalent amounts of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthesized were estimated from radioactivity incorporated into the cellotriose and cellotetraose units quantified as described in Figure 1. Inosine-5′-diphosphatase (IDPase) was determined after phenylmethane sulfonylfluoride (PMSF) inhibition of proteinase K activity in detergent-solubilized membranes. B, Radioactivity incorporated in cellotriose (G4G3G, trimer) and cellotetraose (G4G4G3G, trimer) units relative to the concentration of proteinase K. Control activities of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase were 0.68 pmol μg Golgi protein–1 after 1.5-h incubations. Values are the mean ± variance from two experiments conducted on different days.

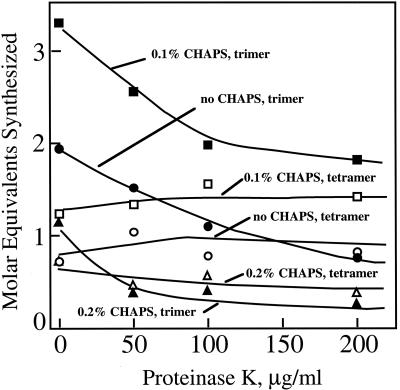

Sub-CMCs of CHAPS Lowers the Proportions of Cellotriose Units Synthesized Selectively

The addition of 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS to intact Golgi membranes enhanced the activity of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase in vitro, with a small enhancement in the molar ratio of cellotriose:cellotetraose. However, 0.2% (w/v) CHAPS decreased the synthase activity substantially relative to controls without detergent and resulted in selective loss of the formation of cellotriosyl units (Fig. 3). The CMC was 0.35% (w/v) CHAPS, judged by the transition from a turbid to a clear solution. Addition of proteinase K to membranes treated with 0.1% or 0.2% (w/v) CHAPS not only decreased (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase activity but also selectively lowered the amount of cellotriose units made relative to cellotetraose units (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Synthesis of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan cellotriose and cellotetraose units upon detergent treatment. CHAPS concentrations are below CMC, and experiments were performed with and without pretreatment with proteinase K at concentrations indicated. Molar equivalent amounts of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthesized as estimated from radioactivity incorporated into the cellotriose (trimer) and cellotetraose (tetramer) units quantified as described in Figure 1. Control activities of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase in 0%, 0.1%, and 0.2% (w/v) CHAPS are 0.70, 1.12, and 0.40 pmol μg protein–1 after 1.5-h incubations with 250 μm UDP-Glc in RB, respectively.

Reconstitution experiments were designed to determine if CHAPS extracted a factor from the surface of the Golgi membrane that could reassociate with the Golgi surface at permissive CHAPS concentration to recover cellotriose-forming activity. Enriched Golgi membranes were incubated in a buffer containing enhancing (0.1% [w/v]) or inhibiting (0.2% [w/v]) concentrations of CHAPS and pelleted by centrifugation. The Golgi membranes were either resuspended directly in the CHAPS-containing buffer, or the supernatant was replaced with fresh CHAPS-containing buffer before resuspension of the membranes. In addition, membranes in 0.2% (w/v) CHAPS were diluted to 0.1% (w/v) before resuspension of the Golgi membranes, or the supernatant was replaced with 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS. Membranes pelleted and resuspended in 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS gave activities of about 0.5 pmol μg protein–1 in a 1-h reaction and a molar ratio of cellotriose:cellotetraose of about 3 (Table I). Total activity was reduced in 0.2% (w/v) CHAPS but less so when CHAPS was diluted to 0.1% (w/v) before assay. The cellotriose: cellotetraose ratios were considerably higher upon dilution of CHAPS from 0.2% to 0.1% (w/v). Replacement of the supernatant of the pelleted membranes resulted in loss of activity in all samples. However, the molar ratio of cellotriose:cellotetraose was 2.5 for membranes constantly incubated in enhancing CHAPS concentrations but was substantially reduced when Golgi membranes were incubated in 0.2% (w/v) CHAPS, and pelleted Golgi membranes were resuspended in a replacement buffer with a normally enhancing concentration of 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS (Table I).

Table I.

Recovery of (1→3), (1→4)-β-glucan cellotriosyl unit synthesis by incubation in CHAPS-permissive concentrations

Golgi membranes were mixed in a stock reaction buffer containing CHAPS to give final concentrations of 0.1% or 0.2% (w/v) and incubated for 15 min at ice temperature. Control reactions remained at ice temperature, whereas paired sets of each treatment were centrifuged to pellet the Golgi membranes. The pelleted Golgi membranes were either resuspended directly in the supernatant or the supernatant was replaced with fresh reaction buffer containing 0.1% or 0.2% (w/v) CHAPS. One set of control samples incubated in 0.2% (w/v) CHAPS was adjusted to 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS before initiation of reactions with labeled substrate. Final volumes of all samples were identical during reactions with UDP-14C-Glc.

| Treatment

|

CHAPS Concentration

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1% (w/v)

|

0.2% →0.1% (w/v)

|

0.2% (w/v)

|

||||

| Activitya | 3 mer/4 merb | Activitya | 3 mer/4 merb | Activitya | 3 mer/4 merb | |

| Control | 1.06 | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 0.48 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 0.42 | 2.0 ± 0.4 |

| Resuspended | 0.96 | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 0.56 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 0.28 | 1.2 ± 0.1 |

| Supernatant replaced | 0.24 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 0.18 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.24 | 1.4 ± 0.5 |

Activities are picomoles of cellotriosyl + cellotetraosyl units formed per microgram of Golgi protein (originally present) after incubations of 1 h. Reactions typically contain 160 ± 15 μg of Golgi membrane protein. Variance of the two samples was ±0.05 or less. b Ratios of cellotriosyl:cellotetraosyl are calculated from molar equivalents of each and are the means ± variance of two samples from experiments conducted on 2 different d.

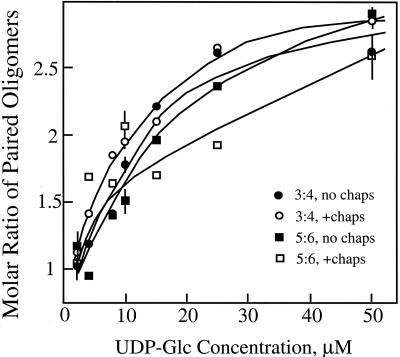

Synthesis of (1→3),(1→4)-β-Glucan Cellotriose and Cellotetraosyl Units Have Different Kinetics with Respect to Concentration of UDP-Glc

The molar ratio of cellotriose:cellotetraosyl units varies from about 0.9:1 at 2 μm UDP-Glc to about 2.8:1 at 50 μm (Fig. 4). The increasing ratios with increasing substrate concentrations were observed when reactions were performed after stimulation of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthesis by treatment of the Golgi membranes with 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS, although cellotriose and cellopentaose formation was slightly enhanced at lower concentrations of UDP-Glc. Parallel concentration-dependent increases in the molar ratios of cellopentaosyl:cellohexaosyl units, from 1:1 at 2 μm UDP-Glc to about 2.8:1 at 50 μm, were observed regardless of incubation in the presence or absence of 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Kinetics of formation of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan cellotriosyl and cellotetraosyl units at low UDP-Glc concentrations. Relative amounts of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthesized as estimated from radioactivity incorporated into the cellotriose through cellohexaose units quantified as described in Figure 1. The radioactivity in each oligomer was divided by the number of Glc units per oligomer to estimate the molar amounts of each. Activities of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase in 2, 10, and 50 μm are 0.03, 0.14, and 0.59 pmol μg protein–1 after 1-h incubations, respectively, and are the means ± sd of three determinations.

Polymer Extension Requires Synthesis of Cellotriosyl Unit

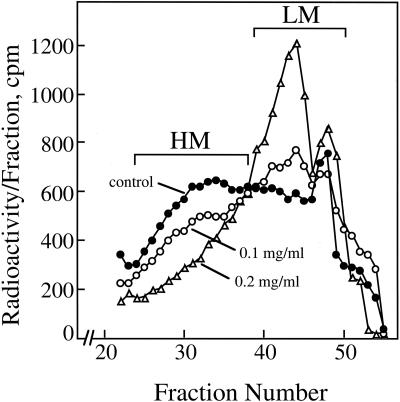

(1→3),(1→4)-β-Glucan synthesized by Golgi membranes in 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS had a molecular mass of up to about 250 kD, whereas pretreatment of the membranes with 0.1 and 0.2 mg mL–1 proteinase K not only selectively decreased the amount of cellotriosyl units synthesized (Fig. 2B) but also greatly decreased the molecular mass of the polymers or oligomers made (Fig. 5). When (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan products were separated by gel-permeation chromatography and then pooled into high- and low-molecular mass forms, nearly 80% of the (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthesized in control samples was of high molecular mass. In contrast, less than 50% of the (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan was recovered from the high-molecular mass fraction when the membranes were pretreated with 0.2 mg mL–1 proteinase K (Table II). With increasing proteinase K concentration, the ratio of cellotriose:cellotetraose units decreased from about 2.8:1 in controls without proteinase to about 1.9:1 after treatment with 0.2 mg mL–1 proteinase K (Table I). The total included fractions containing low-molecular mass (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucans were greatly enriched in cellotetraose relative to cellotriose units, exhibiting cellotriose: cellotetraose rations of only 0.1:0.4:1 (Table II).

Figure 5.

Polysaccharide size as affected by proteinase K and detergent treatment. (1→3),(1→4)-β-Glucan synthesized in vitro in the presence of 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS were incubated with or without pretreatment with 0.1 or 0.2 mg mL–1 proteinase K in reactions containing 250 μm UDP-Glc in RB. After removal of insoluble callose and other material, the soluble (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan product was passed over a 1.7- × 57-cm column of Sepharose 4B-CL equilibrated in 0.1 m Tris[HCl] (pH 7.2), and the radioactivity in a portion of the 3.2-mL fractions was determined by liquid scintillation spectroscopy. The rest of the fractions were pooled into high-molecular mass (HM) and low molecular mass (LM) as indicated, dialyzed against water, and freeze dried. The radioactivity in cellotriose and cellotetraose units in each of these fractions was then determined as described in Figure 1 and presented in Table II.

Table II.

Influence of proteinase K on size and composition of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthesized in vitro

The high- and low-mass fractions pooled for these analyses are shown in Figure 5 (chromatographic profiles of synthase reactions without CHAPS were similar; data not shown). After dialysis against deionized water, the polymers and oligomers were freeze dried, digested with B. subtilis endoglucanase, and cellobiosyl- and cellotetraosyl-(1→3)-glucose oligomers were separated by HPAEC. Radioactivity recovered in each oligomer was corrected for no. of glucose equivalents in the calculation of trimer:tetramer ratios.

| Oligomer

|

No Proteinase

|

0.1 mg mL-1

|

0.2 mg mL-1

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High mass | Low mass | High mass | Low mass | High mass | Low mass | |

| Experiment I: no detergent | ||||||

| Trimer: tetramer | 3.37 | 0.48 | 3.44 | 0.48 | 3.13 | 0.22 |

| % Product | 66.7 | 32.3 | 81.1 | 18.9 | 30.3 | 69.7 |

| Experiment II: + 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS | ||||||

| Trimer: tetramer | 2.75 | 0.44 | 2.44 | 0.14 | 1.88 | 0.21 |

| % Product | 78.3 | 21.7 | 64.1 | 35.9 | 47.9 | 52.1 |

Cellulose Synthesis Inhibitors Do Not Inhibit (1→3),(1→4)-β-Glucan Synthesis

Of the three established cellulose synthesis inhibitors, only 2,6-dichlobenzonitrile (DCB) and isoxaben were able to appreciably affect the synthesis in vitro of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan (Table III). Isoxaben at 5 μm inhibited (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthesis in vitro by about 30%, but higher concentrations did not decrease synthase activity further. Likewise, DCB decreased (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase activity in vitro significantly at 40 and 80 μm but at concentrations much higher than would normally be required to block cellulose synthesis in vivo (Table III).

Table III.

Influence of cellulose synthase inhibitors on (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase activity in vitro

| Inhibitor

|

Concentration

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 10 μm | 20 μm | 40 μm | 80 μm | |

| 14C-Glc incorporated, pmoles μg Golgi protein-1 | |||||

| DCB | 2.65 ± 0.01 | 1.86 ± 0.22 | 2.27 ± 0.35 | 2.07 ± 0.30 | 1.57 ± 0.08 |

| 5

|

10

|

20 μm

|

|||

| 14C-Glc incorporated, pmoles μg Golgi protein-1 | |||||

| Isoxaben | 2.65 ± 0.01 | 1.55 ± 0.28 | 1.69 ± 0.27 | 1.71 ± 0.05 | |

| 1 μm

|

10 μm

|

100 μm

|

1,000 μm

|

||

| 14C-Glc incorporated, pmoles μg Golgi protein-1 | |||||

| CGA325′614 | 3.79 ± 0.03 | 3.92 ± 0.27 | 3.08 ± 0.34 | 3.38 ± 0.19 | 3.12 ± 0.0 |

DISCUSSION

Topology of (1→3),(1→4)-β-Glucan Synthase at the Golgi Membrane

(1→3),(1→4)-β-Glucan biosynthesis in vitro is markedly diminished in intact Golgi vesicles subjected to limited proteolysis, without significant change in IDPase activity (Fig. 2), an enzyme known to reside completely within the Golgi (Morré and Buckout, 1977). We predict that (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase possesses an active site on the cytoplasmic face of the Golgi membrane, with extrusion of the growing polymer into the lumen of the Golgi. Thus, (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase behaves as a topological equivalent of cellulose synthase. In contrast, Muñoz et al. (1996) found that pea (Pisum sativum) xyloglucan synthase is insensitive to proteinase digestion. UDP-Glc transporter function is also resistant to proteolysis in intact Golgi membranes (Neckelman and Orellana, 1998). Muñoz et al. (1996) predicted that the xyloglucan synthase resides completely within the Golgi lumen and is dependent on the translocation of nucleotide-sugar substrates. Similarly, Sterling et al. (2001) also determined the catalytic site of the suspected homogalacturonan biosynthetic enzyme, (1→4)-α-d-galacturonosyltransferase, is inaccessible to proteinase digestion and, therefore, completely contained within the Golgi membrane.

Organization of the (1→3),(1→4)-β-Glucan Synthase at the Golgi Membrane

The loss of β-glucan synthase activity under limited proteolysis conditions is accounted for by loss of cellotriosyl units alone (Fig. 3B). At higher concentrations of proteinase, the capacity to synthesize both units is lost, and, as we reported previously (Urbanowicz et al., 2002), this loss is accompanied by a marked stimulation of callose synthase. Low concentrations (0.1% [w/v]) of CHAPS detergent below the CMC stimulated (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthesis but inhibited synthesis at sub-CMC concentrations of 0.2% (w/v; Fig. 3). Again, the decrease in total (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthesis activity is accounted for by a selective loss of cellotriosyl units, whereas the synthesis of the cellotetraosyl unit is unaffected. As observed with proteinase treatment, the loss of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase coincides with a stimulation of callose synthesis (Urbanowicz et al., 2002). These data indicate that the (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase complex contains at least two separable catalytic activities, one that generates cellotriosyl and a ladder of odd-numbered cellodextrin units and one that generates cellotetraosyl and higher even-numbered units.

Because the cellotriosyl synthesizing activity is dissociable by mild detergent treatment, we suggest that a distinct glucosyl transferase associates with a cellobiosyl-generating core synthase to produce the cellotriosyl and the odd-numbered oligomers. We tested this hypothesis directly in reconstitution experiments with Golgi membranes (Table I). The molar ratios of cellotriose:cellotetraose synthesized could be recovered to any extent in Golgi membranes treated with 0.2% (w/v) CHAPS only when the extract was diluted to 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS. Replacement of the CHAPS extracts at enhancing concentrations results in little loss of cellotriose formation, whereas replacement of the 0.2% (w/v) CHAPS extract with typically enhancing 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS fails to recover the cellotriose formation (Table I). These data indicate the 0.2% (w/v) CHAPS extracts a factor that is able to reconstitute with the Golgi surface when the CHAPS is returned at an enhancing concentration.

The selective loss of cellotriosyl unit synthesis upon proteinase and detergent treatment is similar to an observed decrease in the synthesis of cellotriosyl units at low substrate concentrations (Buckeridge et al., 1999, 2001). Therefore, we examined more closely the kinetics of synthesis of the individual cellodextrin units at limiting concentrations. (1→3),(1→4)-β-Glucan synthase activities not only had different kinetics for the formation of cellotriose and cellotetraosyl units at low substrate concentration, but these differing kinetics were mirrored by cellopentaosyl and cellohexaosyl units, respectively (Fig. 4). Although at the lowest substrate concentrations the molar ratios of cellotriose:cellotetraose and cellopentaose:cellohexaose were both about 1:1, they both rose to 2.8:1 with higher concentrations of UDP-Glc (Fig. 4). The cellotriosyl:cellotetraosyl molar ratio observed in planta is typically 3:1, and this ratio is achieved at substrate concentrations of between 100 and 250 μm UDP-Glc, as the first saturation of cellotriosyl unit formation is approached (Buckeridge et al., 1999). The use of substrate up to 30 mm UDP-Glc in the reaction mixtures precludes the use of radiolabel, but sufficient product is made to be detected electrochemically. At concentrations that approach the second apparent saturation, the (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan product is mostly composed of cellotriosyl and cellopentaosyl units rather than trimer and tetramer, and the changes in the proportions of cellopentaosyl units made parallel those of the cellotriosyl units, not the cellotetraosyl units (Buckeridge et al., 1999, 2001). Therefore, we conclude that the synthesis of the odd-numbered units proceeds by a mechanism distinct from the synthesis of the even-numbered units.

Formation of the Cellotriosyl Unit Is Essential for Polymer Extension

Because the synthesis of the cellotriosyl units is diminished by suboptimal substrate concentrations (Fig. 4), by mild detergent treatment (Fig. 3), and by limited proteolysis (Fig. 2), cellotetraosyl units are a greater proportion of the product. Concomitant with loss of the capacity to synthesize cellotriosyl units is a marked decrease in the size of the product (Buckeridge et al., 1999). In fact, the (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan oligomers comprising the total included fraction of the gel permeation column are largely cellotetraosyl units, even in (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthesized at low substrate concentrations without proteinase or detergent treatment (Fig. 5; Table I). Thus, synthesis of polymeric (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan requires sufficient substrate levels to drive cellotriosyl unit formation. In this aspect, a cooperativity of synthase activities for (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan is similar to that observed for xyloglucan synthesis, where millimolar amounts of UDP-Glc and UDP-Xyl are required to synthesize polymers with the characteristic heptasaccharide unit structure (Gordon and Maclachlan, 1989), and synthesis in the absence of UDP-Xyl produces only short chains of (1→4)-β-d-glucan (Ray, 1980; Hayashi and Matsuda, 1981).

Model of the (1→3),(1→4)-β-Glucan Synthase Complex

(1→3),(1→4)-β-Glucan synthase cannot synthesize cellobiosyl units alone—strictly alternating (1→4)-β- and (1→3)-β-linkages are never observed; therefore, a cellotriosyl unit sandwiched between (1→3)-β-linkages is the minimum cellodextrin unit (Staudte et al., 1983; Wood et al., 1994). The data reported here support a mechanism for the step-wise addition of cellodextrin units coupled by single (1→3)-β-d-glucosyl linkages through an iterative or “processive” action. Processivity is implied by observations of the accumulation of large polymers over time, without synthesis of shorter oligomers, when optimal concentrations of substrate is provided (Buckeridge et al., 1999). Further, three sites or modes of substrate binding and catalysis are contained in the complete (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase. Our data support a model in which a core cellobiosyl-generating system, perhaps related to cellulose synthase, has acquired a distinct glycosyl transferase associated with the core to produce the cellotriosyl unit. Failure of this glycosyltransferase to participate in a round of catalysis, either by failure to fill the active site with UDP-Glc at low substrate concentration, by selective elimination by proteolysis, or by dissociation with detergent, all result in synthesis of predominantly cellotetraosyl, the minimum even-numbered oligomer, and cellohexaosyl units, the next even-numbered unit in the series. Selective lowering of cellotriosyl unit formation by CHAPS treatment below the CMC and the reconstitution of the activity after return to permissive CHAPS concentrations indicates that this transferase activity is dissociable and, hence, a distinct polypeptide. Formation of the cellotriosyl units is correlated with polymer lengthening.

The predicted topology of the catalytic units of a (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase complex assembled at the surface of the Golgi membrane and extrusion of the product into the lumen makes the system subject to additional factors related to membrane status, such as electrical potential or pH gradient. In experiments with excised cotton fibers in which cellulose synthesis was preserved with osmotic agents, an intact membrane was thought to represent a requirement for membrane potential (Carpita and Delmer, 1980). Such a membrane potential requirement was established experimentally with Acetobacter (Delmer et al., 1982). Gibeaut and Carpita (1993) provided evidence that a pH gradient, not an electrical potential, was able to enhance synthesis of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan in vitro.

A role for SuSy in (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase remains another matter for speculation. We detected SuSy in immunogel blots only among maize Golgi membrane polypeptides and not among those from soybean (Buckeridge et al., 1999), and a role for SuSy in metabolic channeling of UDP-Glc, as described for cellulose synthesis (Amor et al., 1995), is attractive. Nevertheless, the synthesis of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan of specific oligomeric distributions is quite sensitive to micromolar concentrations of UDP-Glc concentrations in reactions carried out in the presence of over 1 m Suc. These data indicate that SuSy is either disabled in the reactions in vitro or not involved in the synthesis.

(1→3),(1→4)-β-Glucan synthase is relatively insensitive to three known cellulose synthesis inhibitors. Although some inhibition of activity was observed in the presence of DCB and isoxaben, inhibitory concentrations of these substances are in great excess to concentrations that inactivate cellulose synthesis in vivo (Montezinos and Delmer, 1980; Heim et al., 1990). We interpret this finding to indicate that either the organization of the (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase complex does not allow access of the inhibitors or that they lack the inhibitor binding sites. The inhibitors could also, for example, block an important aggregation of catalytic subunits into a rosette structure, a feature not expected to be involved in the assembly of the (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase. Although the precise biochemical mechanism of inhibition is not known, some recent evidence suggests that CGA 325′615 blocks the crystallization step in cellulose synthesis (Peng et al., 2001) by interfering with an oxidation step involved in coupling of the Zn2+ domains during rosette formation (Kurek et al., 2002). DCB may interfere with the formation with sitosterol-cellodextrins from UDP-Glc in a glycosyl transfer system unique to cellulose. The mechanism of isoxaben inhibition is not known, but two isoxaben-resistant mutants identified in Arabidopsis result from single base changes in non-catalytic domains of CESA genes (Peng et al., 2002). These authors suggest that isoxaben interferes with rosette formation and by blocking the dimerization of CesA polypeptides. Although an involvement of sitosterol-β-glucosides in β-glucan synthesis cannot be ruled out, a mechanism of action of the CGA 325′615 and DCB involving disruption of rosette formation would well explain why (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase is generally insensitive to these inhibitors.

A major problem of the last 4 decades has been to identify the polypeptides that polysaccharide synthases comprise. The necessity of an intact membrane to establish a pH gradient (Gibeaut and Carpita, 1993), and the recognized low abundance of membrane-associated synthases precludes a convenient purification of the (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase complex biochemically. However, discovery of the cellulose synthase gene superfamily has focused the search for candidate polypeptides via deduced sequences (Pear et al., 1996; Richmond and Somerville, 2000). The cellulose synthase genes (CESAs) encode polypeptides of 110 kD that are predicted to be encoded by these genes contain N-terminal Zn2+-finger domains and up to eight membrane-spanning domains sandwiching a large cytosolically located active site. The active site is thought to comprise four “U” motifs, with conserved Asp residues and a QxxRW motif that are considered essential for substrate binding and catalysis (Saxena et al., 1995; Charnock and Davies, 1999). These motifs are conserved in several other genes encoding processive glycosyltransferases in which (1→4)-β-glycosyl structures are synthesized, including chitin synthase, NodC synthase, and hyaluronan synthase (Saxena et al., 1995; Charnock and Davies, 1999). A unique feature of CESAs is a plant specific region that is conserved among plants, and a Class-Specific Region, which possesses motifs of consecutive acidic and basic residues that indicate a role in catalysis, regulation, or protein-protein interaction (Vergara and Carpita, 2001). A phylogenetic tree of the CesA gene family based on their CSR showed that CesA sequences from cereals are more closely related to each other than to those from dicot species. In addition to the CESA family proper, and additional eight families of cellulose synthase-like genes (CSLs) have also been characterized (Delmer, 1999), and several of them are represented in both grasses and non-grasses. However, two classes, CSLF and CSLH, encode polypeptides unique to grasses, whereas two others, CSLB and CSLG, encode polypeptides unique to the dicot representative, Arabidopsis (Hazen et al., 2002). If not a unique subclass member of the CESA family, it is tempting to consider that a core cellobiosyl generating portion β-glucan synthase could be encoded by a member of one of two grass-specific CSL classes. Although a good case could be made that the core synthase is encoded by a member of the CESA/CSL gene superfamily, the search for other catalytic components associated with a core synthase now must be widened to include a special system to generate the fundamental cellotriosyl unit uniquely characteristic of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Isolation of Golgi Membranes

Maize (Zea mays) seeds were soaked in the dark overnight at 30°C in deionized water bubbled with air, then sown in moistened medium-grade vermiculite and grown in darkness for 2 d. Fresh maize coleoptiles and etiolated shoot within were harvested into a chilled mortar and overlain with an equal volume of ice-cold homogenization buffer consisting of 100 mm HEPES[1,3-bis[tris(hydroxymethyl)-methylamino]propane (BTP)] (pH 7.4), 20 mm KCl, and 84% (w/v) Suc. One gram of activated charcoal per 10 g of plant material was co-added with homogenization buffer to absorb inhibitory phenolics released by the maize during gentle mashing (Gibeaut and Carpita, 1993). After mashing, the homogenate was squeezed through nylon mesh (47-μm2 pores), and 20 mL of the homogenate per 38.5-mL Ultraclear centrifuge tube (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA) was overlaid with 8 mL of 34.5% (w/v) Suc in a gradient buffer (10 mm HEPES[BTP] [pH 7.2]), 7 mL of 29% (w/v) Suc in gradient buffer, and 3.5 mL of 9.5% (w/v) Suc in gradient buffer. The Suc gradient was centrifuged at 140,000g in a swinging bucket rotor (model SW28, Beckman Instruments) for 60 min, and the interface enriched in Golgi membranes (34.5%/29% interface) was removed with a Pasteur pipette and used directly for (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase reactions. Protein was determined by bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL). Golgi membrane purity is routinely judged by comparison of the Golgi marker, IDPase (Morré and Buckout, 1977), and a plasma membrane marker, vanadate-sensitive ATPase (Gallagher and Leonard, 1982), as described previously (Gibeaut and Carpita, 1993, 1994b; Buckeridge et al., 1999, 2001). Flotation centrifugation greatly enriches Golgi membranes from contaminating plasma membrane compared with conventional downward centrifugation (Gibeaut and Carpita, 1994b), and IDPase activity is typically enriched 10-fold over the plasma membrane marker (Buckeridge et al., 1999).

β-Glucan Synthase Reactions

(1→3),(1→4)-β-Glucan synthase reactions were initiated by the addition of 0.5 mL of the fresh Golgi preparation to 0.5 mL of RB to give a final concentration of 10 mm HEPES[BTP] (pH 7.4) containing 1.08 m Suc, 20 mm KCl, and 15 mm MgCl2, which, depending on experiment, is supplemented with 0.5 to 2 μCi of UDP-d-[U-14C]Glc (320 mCi mmol–1; Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) and up to 250 μm UDP-Glc (Sigma, St. Louis). All reactions contained 160 ± 15 μg of total Golgi membrane protein. The reaction components were gently mixed and placed at 30°C for up to 1.5 h, depending on the experiment. With 250 μm UDP-Glc, the Golgi membranes generate about 0.75 pmol Glc equivalents of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan μg protein–1 per 1-h reaction. This activity is increased from 45% to 60% in 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS and decreased about 40% in 0.2% (w/v) CHAPS. In some experiments, the substrate additions were adjusted to give final concentrations of between 2 and 50 μm UDP-Glc in RB. As described by Buckeridge et al. (1999), the activities in the absence of CHAPS were about 0.03 and 0.60 pmol Glc equivalents of (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan μg protein–1 in a 1-h reaction with 2 and 50 μm UDP-Glc, respectively. Boiled enzyme preparations were conducted in the presence and absence of 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS in 2 and 250 μm UDP-Glc.

All reactions were stopped by the addition of 3 mL of ethanol. In some instances, 100 μg of authentic barley (Hordeum vulgare) (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan (Sigma) was added at this step as a recovery and elution standard. The reaction mixtures were heated at 105°C for 5 min and then cooled to room temperature and centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000g. The pellet was washed extensively with 80% (v/v) ethanol by heating the sealed vials at 105°C in the oven for 5 min, followed by cooling and recentrifugation. The washed pellets were dried under a stream of nitrogen gas at 45°C. The β-glucan products were dissolved by boiling in water. In some instances, the soluble β-glucans were passed over a Sephadex G-25M desalting column (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) equilibrated in water, recovered from the void fractions, and freeze dried. Portions of reactions in 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS in RB plus 2 and 250 μm UDP-Glc were analyzed without digestion with endo-β-glucanase as control.

Molecular Mass of (1→3),(1→4)-β-Glucans Synthesized in Vitro

Dried pellets remaining after the hot 80% (w/v) ethanol washes were suspended in 2 mL of 0.1 m Tris[HCl] (pH 7.2); the β-glucans in the suspension were solubilized in a sonic bath for 60 min at 60°C, and the undissolved callose was pelleted in a microfuge. The supernatants were then boiled for 2 min just before loading on a 60- × 2.5-cm column of Sepharose 4B-CL equilibrated in 0.1 m Tris[HCl] (pH 7.2). Fractions (3.5 mL) were collected; 2 mL was assayed for radioactivity by liquid scintillation spectroscopy, and the remainders were pooled into high- and low-mass fractions, dialyzed against deionized water, and freeze dried. The distribution of radioactive cellotriose and cellotetraose units in (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucans of these two fractions was determined as described below.

Quantitation of β-Glucan Oligomers

A Bacillus subtilis β-glucan endohydrolase selectively cleaves a (1→4)-β linkage only when it is preceded at the non-reducing end by a (1→3)-β linkage (Anderson and Stone, 1975). The reaction products were resuspended in 100 μL of water, and 20 μL (0.6 μg protein) of a preparation containing β-glucan endohydrolase in 20 mm sodium acetate and 20 mm NaCl (pH 5.5) was added (Gibeaut and Carpita, 1993). The products released from the digestion of purified (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan yield mostly cellobiosyl- and cellotriosyl-(1→3)β-d-Glc (Staudte et al., 1983; Wood et al., 1994). These linkage structures were confirmed by electron impact mass spectrometry of end-reduced, partly methylated oligomers (Carpita and Gibeaut, 1988). The samples were incubated for 3 h at 37°C and stopped by boiling for 2 min, cooled, and microfuged at 14,000 rpm for 5 min. The pellet (containing mostly callose) was resuspended in 1 mL of water, and the radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation spectroscopy (Gibeaut and Carpita, 1993).

The oligomers from β-glucan endohydrolase digestion were separated by HPAEC with an anion-exchange column (Carbo-Pac PA1, Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA) and detected with a pulsed amperometric detector (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA). The column was equilibrated in 0.2 m NaOH, and the samples were eluted in a linear gradient to 0.2 m sodium acetate in 0.2 m NaOH. If not added as an recovery standard, 2.5 μg of predigested barley (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan (Sigma) was added as an HPAEC elution standard. Fractions (0.5 mL) were collected in 1 mL of 1 m acetic acid to neutralize the alkali, and radioactivity as disintegrations per minute was then determined by liquid scintillation spectroscopy. To determine molar ratios, the radioactivity associated with each oligomer was divided by the number of glucosyl residues. As described previously (Gibeaut and Carpita, 1993, 1994; Buckeridge et al., 1999), no radioactivity associated with the four cellodextrin-(1→3)-β-d-Glc oligomers is observed by HPAEC in the absence of endohydrolase digestion. The identity of the four oligomers also has been determined by GLC-MS of partly methylated, end-reduced oligomers as reported previously (Carpita and Gibeaut, 1988; Gibeaut and Carpita, 1993).

Limited Proteolysis and Detergent Treatments

The (1→3),(1→4)-β-glucan synthase assay was adjusted to accommodate additions of detergent and/or proteinase K. Experiments were initiated by the addition of 0.75 mL of the Golgi membrane preparation to 0.6 mL of CHAPS in RB to reach final concentrations indicated. A CHAPS pretreatment was carried out at 4°C for 30 min. Proteinase K (EC 3.4.21.64, Sigma) in RB was then added to reach concentrations indicated in a final reaction volume of 1.5 mL, and the mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 30 min. Samples were placed on ice, and 10 μL of 50 mm PMSF (in ethanol) was added to block further proteinase digestion. One-half milliliter of the reaction was removed for IDPase assays, and in 0.1 mL of RB containing 1 μCi of UDP-d-[U-14C]Glc in 250 μm UDP-Glc was added to the remaining 1-mL samples to initiate synthesis of radiolabeled β-glucan. The incubations continued an additional 90 min at 30°C before addition of 3 mL of ethanol followed by heating to 105°C as described earlier.

The IDPase assays were performed essentially as described by Morré and Buckout (1977). However, all samples were adjusted to the highest level of proteinase K and then blocked with PMSF to correct equally for any residual proteinase activity after detergent extraction of the Golgi membranes. Assays are conducted in 0.05% (w/v) Triton X-100 to access IDPase in the Golgi lumen (Morré and Buckout, 1977).

Reconstitution of (1→3),(1→4)-β-Glucan Synthase with Isolated Golgi Membranes

Experiments were initiated by the addition of 0.5 mL of the Golgi membrane preparation to 0.25 to 0.5 mL of CHAPS in RB to reach final concentrations of 0.1% to 0.2% (w/v), and the mixtures were incubated at 4°C for 15 min. In one set of experiments, the preparations were centrifuged at 140,000g to pellet Golgi membranes from the CHAPS-soluble fractions. The Golgi pellet was either resuspended directly in the CHAPS-soluble supernatant, or the supernatant was replaced with fresh CHAPS in RB to give the desired concentration. In some instances, Golgi membranes incubated in 0.2% were adjusted to 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS before resuspension or the supernatant was replaced with 0.1% (w/v) CHAPS. Control reactions were incubated in CHAPS media without centrifugation. All reactions were initiated by addition of 2 μCi of UDP-d-[U-14C]Glc to 0.5 mL of RB was added to the preparations to initiate synthesis of radiolabeled β-glucan at a final concentration of 250 μm UDP-Glc. Reactions were 60 min at 30°C before addition of 2.5 mL of ethanol followed by heating to 105°C to stop reactions.

Cellulose Synthesis Inhibitors

The reactions were performed as stated previously with the additions of known cellulose synthase inhibitors: DCB (Thompson-Hayward Chem. Co., Fresno, CA), isoxaben (a gift from Ignacio Larrinua, Dow AgroSciences, Zionsville, IN), and CGA 325′615 (a gift from Karl Kreutz, Syngenta, Basel). Stock solutions of 32 mm DCB in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were used to give final concentrations of up to 80 μm, 8 mm isoxaben in DMSO to give up to 20 μm, and 0.4 mm CGA 325′615 to give final concentrations of up to 1 μm. Each sample had a final concentration of 0.25% (w/v) DMSO.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Marcos Buckeridge and Marco Tiné (Botanical Institute of São Paulo, Brazil) for valuable discussions at early stages of these experiments. We also thank Dr. Bruce Stone (La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia) for his valuable comments on an early draft of this manuscript.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.103.032011.

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Biosciences (grant to N.C.C.). This is journal paper no. 17,218 of the Purdue University Agricultural Experiment Station.

References

- Amor Y, Haigler CH, Johnson S, Wainscott M, Delmer DP (1995) A membrane-associated form of sucrose synthase and its potential role in synthesis of cellulose and callose in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 9353–9357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MA, Stone BA (1975) A new substrate for investigating the specificity of β-glucan hydrolases. FEBS Lett 52: 202–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckeridge MS, Vergara CE, Carpita NC (1999) Mechanism of synthesis of a cereal mixed-linkage (1→3),(1→4)-β-d-glucan: evidence for multiple sites of glucosyl transfer in the synthase complex. Plant Physiol 120: 1105–1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckeridge MS, Vergara CE, Carpita NC (2001) Insight into multi-site mechanisms of glycosyl transfer in (1→4)-β-d-glycan synthases provided by the cereal mixed-linkage (1→3),(1→4)-β-d-glucan synthase. Phytochemistry 57: 1045–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita NC (1996) Structure and biogenesis of the cell walls of grasses. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 47: 445–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita NC, Defernez M, Findlay K, Wells B, Shoue DA, Catchpole G, Wilson RH, McCann MC (2001) Cell wall architecture of the elongating maize coleoptile. Plant Physiol 127: 551–565 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita NC, Delmer DP (1980) Protection of cellulose synthesis in detached cotton fibers by polyethylene glycol. Plant Physiol 66: 911–916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita NC, Gibeaut DM (1988) Biosynthesis and secretion of plant cell wall polysaccharides. Curr Top Plant Biochem Physiol 7: 112–133 [Google Scholar]

- Carpita NC, Vergara CE (1998) A recipe for cellulose. Science 279: 672–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita NC, McCann M, Griffing LR (1996) The plant extracellular matrix: news from the cell's frontier. Plant Cell 8: 1451–1463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charnock SJ, Davies GJ (1999) Structure of the nucleotide diphospho-sugar transferase, SpsA from Bacillus subtilis, in native and nucleotide-complexed forms. Biochemistry 38: 6380–6385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmer DP (1999) Cellulose biosynthesis: exciting times for a difficult field of study. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 50: 245–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmer DP, Benziman M, Padan E (1982) Requirement for a membrane potential for cellulose synthesis in intact cells of Acetobacter xylinum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 79: 5282–5286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincher GB (1992) Cell wall metabolism in barley. In PR Shewry, ed, Barley: Genetics, Biochemistry, Molecular Biology and Biotechnology. CAB International, Wallingford, UK, pp 413–437

- Gallagher SR, Leonard RT (1982) Effect of vanadate, molybdate, and azide on membrane-associated ATPase and soluble phosphatase activities of corn roots. Plant Physiol 70: 1335–1340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibeaut DM, Carpita NC (1993) Synthesis of (1→3),(1→4)-β-d-glucan in the Golgi apparatus of maize coleoptiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 3850–3854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibeaut DM, Carpita NC (1994a) Biosynthesis of plant cell wall polysaccharides. FASEB J 8: 904–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibeaut DM, Carpita NC (1994b) Improved recovery of (1→3),(1→4)-β-d-glucan synthase activity from Golgi apparatus of Zea mays (L) using differential centrifugation. Protoplasma 180: 92–97 [Google Scholar]

- Gordon R, Maclachlan G (1989) Incorporation of UDP-[14C]glucose into xyloglucan by pea membranes. Plant Physiol 91: 373–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Matsuda K (1981) Biosynthesis of xyloglucan in suspension cultured soybean cells: occurrence and some properties of xyloglucan 4-β-d-glucosyltransferase and 6-α-d-xylosyltransferase. J Biol Chem 256: 1117–1122 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazen SP, Scott-Craig JS, Walton JD (2002) Cellulose synthase-like genes of rice. Plant Physiol 128: 336–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim DR, Skomp JR, Tschabold EE, Larrinua IM (1990) Isoxaben inhibits the synthesis of acid insoluble cell wall materials in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol 93: 695–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurek I, Kawagoe Y, Jacob-Wilk D, Doblin M, Delmer DP (2002) Dimerization of cotton fiber cellulose synthase catalytic subunits occurs via oxidation of the zinc-binding domains Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 11109–11114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montezinos D, Delmer DP (1980) Characterization of inhibitors of cellulose synthesis in cotton fibers. Planta 148: 305–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morré DJ, Buckout TJ (1977) Isolation of the Golgi apparatus. In E Reid, ed, Plant Organelles. Horwood, Chichester, UK, pp 117–134

- Muñoz P, Norambuena L, Orellana A (1996) Evidence for a UDP-glucose transporter in Golgi apparatus-derived vesicles from pea and its possible role in polysaccharide biosynthesis. Plant Physiol 112: 1585–1594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neckelman G, Orellana A (1998) Metabolism of uridine 5′-diphosphate-glucose in Golgi vesicles from pea stems. Plant Physiol 117: 1007–1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pear JR, Kawagoe Y, Schreckengost WE, Delmer DP, Stalker DM (1996) Higher plants contain homologs of the bacterial celA genes encoding the catalytic subunit of cellulose synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 12637–12642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng LC, Xiang F, Roberts E, Kawagoe Y, Greve LC, Kreuz K, Delmer DP (2001) The experimental herbicide CGA 325′615 inhibits synthesis of crystalline cellulose and causes accumulation of non-crystalline β-1,4-glucan associated with CesA protein. Plant Physiol 126: 981–992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng LC, Kawagoe Y, Hogan P, Delmer D (2002) Sitosterol-β-glucoside as primer for cellulose synthesis in plants. Science 295: 147–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray PM (1980) Cooperative action of β-glucan synthetase and UDP-xylose xylosyltransferase of Golgi membranes in the synthesis of xyloglucan-like polysaccharide. Biochim Biophys Acta 629: 431–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond TA, Somerville CR (2000) The cellulose synthase superfamily. Plant Physiol 124: 495–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena IM, Brown RM Jr, Fevre M, Geremia RA, Henrissat B (1995) Multidomain architecture of β-glucosyl transferases: implications for mechanism of action. J Bacteriol 177: 1419–1424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BG, Harris PJ (1999) The polysaccharide composition of Poales cell walls: Poaceae cell walls are not unique. Biochem Syst Ecol 27: 33–53 [Google Scholar]

- Staudte RG, Woodward JR, Fincher GB, Stone BA (1983) Water-soluble (1→3),(1→4)-β-d-glucans from barley (Hordeum vulgare) endosperm: III. Distribution of cellotriosyl and cellotetraosyl residues. Carbohydr Polym 3: 299–312 [Google Scholar]

- Sterling JD, Quigley HF, Orellana A, Mohnen D (2001) The catalytic site of the pectin biosynthetic enzyme α-1,4-galacturonosyltransferase is located within the lumen of the Golgi. Plant Physiol 127: 360–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanowicz B, Rayon C, Carpita NC (2002) Biochemical mechanisms of synthesis of (1→3),(1→4)β-d-glucan synthase: cellulose synthase with an added twist? In D Renard, Della Valle G, Y Popineau, eds, Plant Biopolymer Science: Food and Non-Food Applications. Royal Society London, pp 3–12

- Vergara CE, Carpita NC (2001) β-d-Glucan synthases and the CesA gene family: lessons to learned from the mixed-linkage (1→3),(1→4)-β-d-glucan synthase. Plant Mol Biol 47: 145–160 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood P, Weisz J, Blackwell BA (1994) Structural studies of (1→3),(1→4)-β-d-glucans by 13C-nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and by rapid analysis of cellulose-like regions using high-performance anion-exchange chromatography of oligosaccharides released by lichenanase. Cereal Chem 71: 301–307 [Google Scholar]