Abstract

To investigate the molecular basis of the voltage sensor that triggers excitation–contraction (EC) coupling, the four-domain pore subunit of the dihydropyridine receptor (DHPR) was cut in the cytoplasmic linker between domains II and III. cDNAs for the I-II domain (α1S 1–670) and the III-IV domain (α1S 701-1873) were expressed in dysgenic α1S-null myotubes. Coexpression of the two fragments resulted in complete recovery of DHPR intramembrane charge movement and voltage-evoked Ca2+ transients. When fragments were expressed separately, EC coupling was not recovered. However, charge movement was detected in the I-II domain expressed alone. Compared with I-II and III-IV together, the charge movement in the I-II domain accounted for about half of the total charge (Qmax = 3 ± 0.23 vs. 5.4 ± 0.76 fC/pF, respectively), and the half-activation potential for charge movement was significantly more negative (V1/2 = 0.2 ± 3.5 vs. 22 ± 3.4 mV, respectively). Thus, interactions between the four internal domains of the pore subunit in the assembled DHPR profoundly affect the voltage dependence of intramembrane charge movement. We also tested a two-domain I-II construct of the neuronal α1A Ca2+ channel. The neuronal I-II domain recovered charge movements like those of the skeletal I-II domain but could not assist the skeletal III-IV domain in the recovery of EC coupling. The results demonstrate that a functional voltage sensor capable of triggering EC coupling in skeletal myotubes can be recovered by the expression of complementary fragments of the DHPR pore subunit. Furthermore, the intrinsic voltage-sensing properties of the α1A I-II domain suggest that this hemi-Ca2+ channel could be relevant to neuronal function.

In voltage-dependent ion channels, such as Na+, K+, and Ca2+ channels, the opening of the ion-selective pore is coupled to movement of intramembrane charges, the so-called gating charges, buried in transmembrane segments in the channel. The consensus membrane topology of these channels is either six transmembrane segments in each of four subunits (in the case of K+ channels) or six transmembrane segments (S1-S6) in each of four internal repeats or domains (I-IV) joined by cytosolic linkers (in the case of Na+ and Ca2+ channels) (1). Movement of the gating charges in response to voltage involves a substantial reorientation of transmembrane segments S4 and possibly S3 bearing the gating charges (2). Such a conformational change facilitates the energetically unfavorable opening of the ion-selective pore.

Skeletal muscle cells use the movement of gating charges in the Ca2+ channel formed by the dihydropyridine receptor (DHPR) to release Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). The coupling mechanism presumably involves voltage-dependent gating transitions in the DHPR α1S pore subunit, transmission of a conformation change across the transverse tubule/SR junction, and, ultimately, opening of the ryanodine receptor (RyR1) channel and release of SR-stored Ca2+ (3). The biophysical characteristics of the charge movements that initiate excitation–contraction (EC) coupling have been thoroughly investigated (3, 4). A strong correlation was found between the movement of the so-called suprathreshold charges and the rate of SR Ca2+ release (5). This correlation holds over a wide range of voltages and suggests that muscle charge movements represent surrogate “gating charges” for the opening of the RyR1 channel. This suggestion is made explicit in a kinetic model in which opening of the RyR1 channel is coupled with an allosteric mechanism for voltage-dependent transitions in the DHPR (6).

The molecular basis of how charge movements in the DHPR put EC coupling in motion are unknown. Specifically lacking is information about (i) how the four S4 domains of α1S orchestrate charge movements and (ii) how charge movements orchestrate the conformation change sensed by the RyR1. These crucial steps are difficult to approach experimentally because EC coupling is completed in a few milliseconds (7) and because there is a bona fide free energy transduction from electrical to chemical that is inherently difficult to measure. Substantial knowledge on the voltage sensor of K+ channels relevant to how the four S4 domains of α1S orchestrate charge movements is now available (2). It is still unclear, however, how this information might apply to DHPR charge movements, because unlike in the K+ channel, the four S4 domains of α1S exhibit unique differences in charge composition.

Here we show that EC coupling can be initiated by coexpression of complementary fragments of α1S produced by cutting α1S in the cytoplasmic loop linking repeats II and III. The data suggest that each half of the α1S subunit contributes to charge movements essential to EC coupling and that interactions between the two halves of the molecule are responsible for the characteristics of charge movements seen in the native DHPR. Interestingly, two-domain fragments of the Ca2+ and Na+ channel, produced by alternative gene splicing, have been cloned from newborn skeletal muscle, fetal brain, and nonneuronal tissues (8–10). The cellular functions of these endogenous two-domain Ca2+ channel fragments remain to be elucidated. We provide evidence that a two-domain form of the neuronal α1A subunit (11) possesses intrinsic voltage-sensing capabilities that could be relevant to neuronal function.

Materials and Methods

Primary Cultures and cDNA Transfection.

Outbred Black Swiss mice (Charles River Breeding Laboratories) were used to generate heterozygous muscular dysgenesis gene locus mdg/+ parents. Primary cultures were prepared from enzyme-digested hind limbs of dysgenic (mdg/mdg) embryos (on embryonic day 18) as described (12). cDNAs were subcloned into the mammalian expression vectors pSG5 (Stratagene) or pCDNA3 (Invitrogen). cDNAs of interest and a separate expression vector encoding the T cell membrane antigen CD8 were mixed and cotransfected with the polyamine LT-1 (Panvera, Madison, WI). In the case of the neuronal α1A I-II construct, cells were also contransfected with a rat β4a cDNA (GenBank L02315) subcloned into the pSG5 vector to increase charge movement expression. Whole-cell recordings were made and immunostaining was done 3–5 days after transfection. Cotransfected cells were recognized by incubation with CD8 antibody beads (Dynal, Oslo). The coincidence of expression of CD8 and a cDNA of interest was >85%.

cDNA Constructs.

α1S 1–1873.

A full-length rabbit α1S cDNA (residues 1–1873; GenBank M23919) was fused in frame to the first 11 aa of the phage T7 gene 10 protein in the pSG5 vector with the use of AgeI and NotI cloning sites. Primers for subcloning into pSG5 had 20–25 bases identical to the original sequence plus an additional 10–15 bases to introduce an AgeI site at the 5′ end, and a stop codon and NotI site at the 3′ end. The PCR products were subcloned into the pCR-Blunt vector (Invitrogen), excised by digestion with AgeI and NotI, and cloned into pSG5.

α1S Δ671–690.

The α1S 1–1873 fragment from AgeI (nt −20) to XhoI (nt 2653) was sublcloned into pBlueKs+ (Stratagene). PCR primers were designed for deletion nt 2009 to 2069 (T671-L690) and introduction of a unique HindIII site at nt 2004 for identification of mutant clones. This cDNA was subcloned, with the use of AgeI and XhoI sites, in frame to the first 11 aa of the phage T7 gene 10 protein in the pSG5 vector.

α1S 1–670.

pSG5 with the α1S Δ671–690 insert was digested with HindIII and NotI to remove the 3.5-kb fragment from nt 2004 to 5592 (end of a reading frame).The pSG5 containing the N-terminal fragment was gel purified, blunted, and ligated with a 10-mer amber linker (New England Biolabs). Sequence mismatches introduced by the amber linker were removed with the use of suitable primers.

α1S 701-1873.

pSG5 with the α1S 1–1873 was digested with AgeI and HindIII enzymes to remove a 2-kb N-terminal fragment (nt −20 to 2003). The digest was filled to blunt end, diluted, and ligated.

α1A 1–1218.

The α1A I-II was assembled from a full-length rabbit α1A cDNA (GenBank X57477). The 2.5-kb HindIII-HindIII fragment was cut out and subcloned into the mammalian expression vector pCDNA3 (Invitrogen). The plasmid was then cut with Bsg I and ApaI, and the 1.6-kb BsgI-ApaI fragment from the α1A (nt 2364–3948) was ligated. The expression of the construct was confirmed by in vitro translation and Western blot analysis.

Whole-Cell Voltage Clamp.

Myotubes were voltage-clamped with the use of an Axopatch 200B (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). The external solution was (in mM) 130 tetraethylammonium-methanesulfonate, 10 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes-tetraethylammonium(OH) (pH 7.4). The pipette solution was (in mM) 140 Cs-aspartate, 5 MgCl2, 0.1 EGTA (for Ca2+ transients) or 5 EGTA (all others), 10 4-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid–CsOH (pH 7.2). For recording of nonlinear charge movement, the external solution was supplemented with 0.5 mM CdCl2, 0.5 mM LaCl3, and 0.05 mM tetrodotoxin. The internal solution was 120 N-methyl glucamine-glutamate, 10 Hepes-N-methyl glucamine, 10 EGTA-N-methyl glucamine (pH 7.3). The charge movement protocol included a long prepulse to inactivate Na+ channel ionic and gating currents. Voltage was stepped from a holding potential of −80 mV to −35 mV for 750 ms, then to −50 mV for 5 ms, then to the test potential for 50 ms, then to −50 mV for 30 ms, and finally to the −80 mV holding potential. Nonlinear charge movement from a more negative holding potential, −120 mV, resulted in Q-V curves with the same maximum charge movement density (13). On-line subtraction of the linear charge was done with the use of P/4 pulses (delivered preprotocol) from −80 mV in the negative direction. The voltage dependence of charge movements (Q), peak intracellular Ca2+ (ΔF/F), and Ca2+ conductance (G) was fitted according to a Boltzmann distribution, A = Amax/(1 + exp(−(V − V1/2)/k)). Amax is Qmax, ΔF/Fmax, or Gmax; V1/2 is the potential at which A = Amax/2; and k is the slope factor.

Confocal Fluorescence Microscopy.

Line scans were performed as described (14) in cells loaded with 4 μM fluo-4 acetoxymethyl ester (Molecular Probes) for ≈30 min at room temperature. Cells were viewed with an inverted Olympus microscope with a 20× objective (N.A. = 0.4) and a Fluoview confocal attachment (Olympus, New Hyde Park, NY). Excitation light was provided by a 5-mW argon laser attenuated to 20% with neutral density filters. For immunofluorescence, confocal images had dimensions of 1024 × 1024 pixels (0.35 μm per pixel) and were obtained with a 40× oil-immersion objective (N.A. 1.3).

Immunostaining.

Cells were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence as described (15). The I-II fragment was identified with a mouse monoclonal antibody against aT7 epitope fused to the N terminus of α1S. The III-IV fragment was identified with SKC, a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the C terminus of α1S (G1860-P1873) or SKI, a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the II-III loop of α1S (A739-I752). SKC and SKI had been characterized (16). The anti-T7 antibody (Novagen) was used at a dilution of 1:1000. SKC and SCI were used at a dilution of 1:75. Secondary antibodies were a fluorescein-conjugated goat anti mouse IgG (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) used at a dilution of 1:1,000 and a fluorescein-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Chemicon) used at a dilution of 1:1,000.

Results

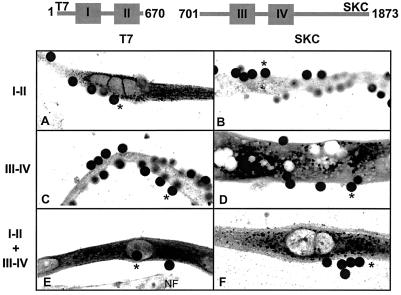

Expression of the I-II and III-IV protein fragments was established by immunostaining of cDNA transfected cells with antibodies against the C terminus (SKC) and the tagged N terminus (T7) of α1S. Confocal images of myotubes expressing each or both fragments plus the CD8 marker are shown in Fig. 1. The images show that the fragments, alone (Fig. 1 A and D) or in combination (Fig. 1 E and F), were expressed abundantly in dysgenic cells. Furthermore, there was no detectable expression of the α1S C terminus epitope in cells transfected with the I-II cDNA (Fig. 1B), and the N terminus epitope was absent in cells transfected with the III-IV cDNA (Fig. 1C). For comparison, a nontransfected cell in the same confocal plane as the transfected cell is indicated in Fig. 1E. We found abundant fragment expression in the periphery of cell nuclei, presumably in the endoplasmic reticulum, as well as in the periphery of the cell. The staining pattern varied between mostly diffuse (Fig. 1E) and mostly punctate (Fig. 1F), although we could not find a correlation between the staining pattern and the expressed fragment. In adult skeletal muscle, the C terminus of α1S is cleaved but possibly not separated from the rest of the DHPR (16). For this reason, we also followed expression of the III-IV fragment with SKI Ab generated against a sequence present at the N terminus of the III-IV domain (see Materials and Methods). The level of expression of the III-IV domain detected by SKI Ab was qualitatively the same. Western blots of transfected cultures of mytotubes showed that the I-II domain migrated as a 85-kDa protein and the III-IV domain as a 140-kDa protein, consistent with the expected molecular masses of 76 kDa and 132 kDa, respectively (not shown).

Figure 1.

Confocal immunofluorescence of dysgenic myotubes expressing DHPR fragments. Confocal images (42 × 18 μm) show details of the intracellular distribution of the expressed fragments. Cells were transfected with the CD8 cDNA plus the following: I-II cDNA (A and B), III-IV cDNA (C and D), and I-II + III-V cDNAs (E and F). Cells were incubated with CD8 antibody beads, fixed, and stained with T7 (A, C, and E) or SKC (B, D, and F) primary/fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibodies. Pixel intensity was converted to a 16-level inverted gray scale, with high-intensity pixels in black. Asterisks show on-focus CD8 antibody beads (diameter 4.5 μm) bound to cells expressing the indicated fragment(s). NF indicates a nontransfected myotube in the same focal plane of the transfected cell.

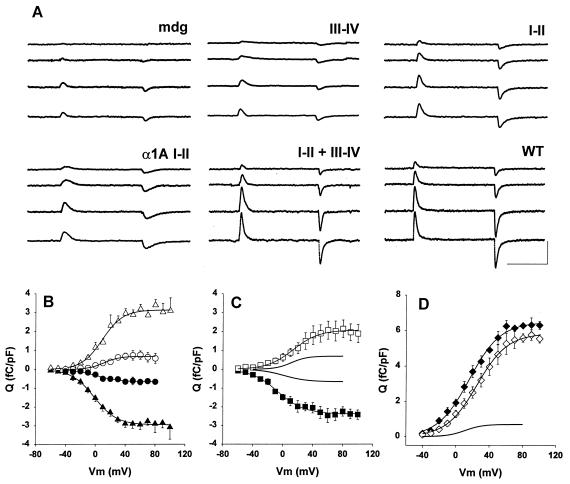

To determine whether the I-II and III-IV fragments were targeted to the plasma membrane and expressed functional voltage sensors, we used a gating current protocol. We measured the nonlinear component of charge movement after on-line subtraction of the linear component with P/4 pulses from −80 mV. Fig. 2A shows “gating”-type currents (i.e., transient currents produced by the nonlinear component of intramembrane charge movement) in myotubes expressing one or both fragments. Each trace consists of an outward current at the start of a 50-ms voltage step as the charges move in the outward direction followed by an inward current at the end of the voltage step as charges return to the original position. In cells expressing the III-IV fragment, we did not detect specific charge movement, that is, charge movement larger than the background component that was always present in nontransfected cells. This background component had a maximum density, Qmax, of less than 1 fC/pF (Fig. 2B, circles). Presumably, the expressed III-IV fragment was not targeted to the plasma membrane in amounts discernible by the technique. In contrast, the I-II domain and a neuronal I-II domain of the Ca2+ channel pore subunit α1A (11) generated a charge movement 2- or 3-fold above the background density. Furthermore, I-II and III-IV together produced charge movement twice as large as I-II alone and similar in density and kinetics to that of full-length α1S. This result suggested that the I-II domain had the ability to recruit charges from the III-IV domain, most likely by helping to target the III-IV fragment to the cell membrane (see Discussion). However, this targeting was not a generic function of the I-II domain, inasmuch as the neuronal I-II domain coexpressed with the skeletal III-IV domain did not generate additional charge movement (not shown). The voltage dependence of the ON charge and the OFF charge is shown for cells expressing the skeletal I-II (Fig. 2B) or the neuronal I-II (Fig. 2C) domains. The ON charge was integrated from the current trace when the voltage was stepped to a positive potential (empty symbols). The OFF charge was plotted in the negative direction and was integrated when the voltage was stepped back to −80 mV (filled symbols). The ON and OFF components increased with the step potential in a sigmoidal manner and saturated at positive potentials. For the I-II domain and for the α1A I-II domain, the total charge (Qmax) that moved during the ON and OFF phases was indistinguishable (P < 0.05). These characteristics of the charge movement, namely, a sigmoidal voltage dependence, saturation at large positive potentials, and equality of ON and OFF components, are consistent with a recovery of functional voltage-sensing domains. Also consistent with this idea was the fact that I-II and III-IV together recovered large gating-type currents. When integrated, the maximum charge and the voltage dependence of charge movement were similar to those of myotubes transfected with full-length α1S (Fig. 2D). Hence the I-II domain and the III-IV domain, although expressed as separate fragments, could assemble into a functional DHPR voltage sensor. A cell-by-cell analysis of these data (Table 1) showed that the charge movement produced by the two fragments together had Boltzmann parameters indistinguishable from those produced by full-length α1S (P < 0.05). Also significant was the fact that the charge movement generated by the I-II fragment had a half-activation voltage, V1/2, ≈20 mV more negative than the V1/2 of I-II plus III-IV together or that of full-length α1S (P < 0.05). This result seems to indicate that in the assembled four-domain DHPR voltage sensor, the gating characteristics of the I-II domain are modified significantly, presumably by interdomain interactions with domains III and IV.

Figure 2.

Expression of intramembrane charge movements by skeletal and neuronal two-domain fragments. (A) Gating-type currents in myotubes expressing the indicated fragment, nontransfected (mdg), and full-length α1S (WT). The 50-ms step potentials are −10, 10, 50, and 70 mV. The cell capacitance was (in pF) 281 (mdg), 290 (I-II), 317 (III-IV), 242 (I-II + III-IV), 260 (full-length α1S, WT), and 260 (α1A I-II). (Calibration bars are 25 ms and 0.5 nA.) (B–D) Q-V curves for mdg (B, ○, ●), I-II (B, ▵, ▴), α1A I-II (C, □, ■), I-II + III-IV (D, ⋄), and WT (D, ♦). In B and C, the ON charge is positive and the OFF charge is negative. In D, only the OFF charge is shown. Curves correspond to a Boltzmann fit of the population mean Q-V curve. Parameters of the fit are (B) Qmax ON = 0.7, 3.1 fC/pF; Qmax OFF = −0.66, −3 fC/pF; V1/2 ON = 1.1, 9 mV; V1/2 OFF = 1.3, 1.6 mV; k ON = 10.5, 15.2 mV, k OFF = 15.5, 13.8 mV for mdg and I-II, respectively. (C) Qmax ON = 2.1 fC/pF; Qmax OFF = −2.4 fC/pF; V1/2 ON = 6.8 mV; V1/2 OFF = −3.6 mV; k ON = 17.2 mV, k OFF = 17.7 mV for α1A I-II. (D) Qmax OFF = 5, 5.3 fC/pF; V1/2 OFF = 25, 22 mV; k OFF = 18.2, 18.5 mV for I-II + III-IV and WT, respectively. (C, D) The curve without symbols is a fit of the Q-V curve of mdg cells.

Table 1.

Ca2+ conductance, charge movement, and Ca2+ transients expressed by two-domain Ca2+ channel fragments

|

Q-V

|

ΔF/F-V

|

G-V

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qmax, fC/pF | V1/2, mV | k, mV | ΔF/F(max) | V1/2, mV | k, mV | Gmax, pS/pF | V1/2, mV | k, mV | |

| mdg | 0.8 ± 0.15*† (12) | −1.7 ± 3.7 | 11.9 ± 2.2 | — (24) | — | — | — (45) | — | — |

| I–II | 3 ± 0.23*‡ (7) | 0.2 ± 3.5¶ | 13.5 ± 1.4 | — (8) | — | — | — (11) | — | — |

| α1A I–II | 2.5 ± 0.24†§ (6) | −0.4 ± 6.5∥ | 17 ± 3.4 | — (7) | — | — | — (7) | — | — |

| I–II + III–IV | 5.4 ± 0.76‡§ (6) | 22.2 ± 3.4¶∥ | 16.1 ± 1.2 | 3.1 ± 0.1 (15) | 10 ± 3 | 9.7 ± 0.3 | 66 ± 11.8** | 27 ± 2.3 | 5.6 ± 0.3 |

| WT α1S | 6.4 ± 0.27 (7) | 19.5 ± 2.8 | 20.5 ± 1.5 | 3.2 ± 0.4 (6) | 12.8 ± 0.9 | 8.9 ± 1 | 99 ± 0.7 (9) | 25 ± 2 | 3 ± 0.7 |

| α1SΔ671–690 | 5.8 ± 0.28 (6) | 17 ± 2.1 | 19.2 ± 2.2 | 3.1 ± 0.4 (11) | 10.9 ± 1.6 | 10.2 ± 1 | 96 ± 11.2 (6) | 33 ± 3.9 | 4.4 ± 1 |

Entries correspond to mean ± SEM of Boltzmann parameters fitted to each cell. The number of cells is in parentheses. In nontransfected cells (mdg) and cells expressing the I–II or the α1A I–II fragments, conflocal fluo-4 fluorescence increase and L-type Ca2+ current were below detection (<0.2ΔF/F, <20 pA per cell).

†‡§¶∥ Data sets with t test significance P < 0.05.

Parameters of 7 of 26 cells with detectable Ca2+ current.

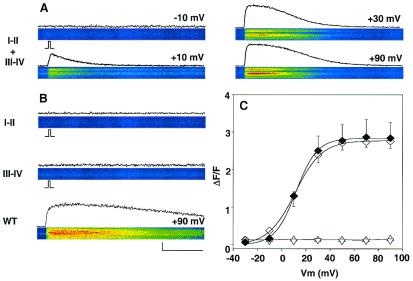

Consistent with the recovery of a functional voltage sensor, the coexpressed I-II and III-IV fragments produced a complete recovery of Ca2+ transients in 15 of 15 cells collected from five separate batches of cells transfected with both cDNAs and the CD8 marker (Fig. 3A). This was not the case when each fragment was expressed alone (Fig. 3B) or when the skeletal III-IV fragment was coexpressed with the neuronal I-II fragment (not shown).The Ca2+ transients of myotubes expressing I-II and III-IV together had characteristics typical of a Ca2+ entry-independent skeletal-type EC coupling. First, no L-type Ca2+ current was recorded from the myotube in Fig. 3A, during a 50-ms depolarization used to stimulate the Ca2+ transient or during a longer 500-ms pulse (not shown). In fact, L-type Ca2+ current was recovered in only 4 of the 15 cells coexpressing I-II and III-IV that were analyzed for Ca2+ transients. Cells expressing Ca2+ current had a ΔF/Fmax = 3.3 ± 0.14 (n = 4), and cells with no detectable Ca2+ current (<20 pA per cell) had a ΔF/Fmax = 3.0 ± 0.18 (n = 11; P = 0.38). Furthermore, there were no differences in Qmax between these two groups of cells (5.7 ± 0.7 vs. 6.1 ± 0.14 fC/pF, respectively; P = 0.47). Second, the confocal line scans showed that Ca2+ transients at +30 mV and +90 mV were nearly identical despite a more than 10-fold difference in L-type Ca2+ current expected at the two potentials. Finally, the Boltzmann parameters of the population averaged Ca2+ fluorescence vs. voltage curve were indistinguishable from those produced by full-length α1S (Fig. 3C). This correlation is also indicated in cell-by-cell analyses of the data in Table 1. The identical shape of the Ca2+ transient vs. voltage curve demonstrated that the two complementary fragments of α1S produced a quantitative recovery skeletal-type EC coupling. This result could only be possible if significant levels of both two-domain fragments were expressed on the same cell (consistent with Fig. 1), the fragments assembled into functional voltage sensors (consistent with Fig. 2), and those voltage sensors became integrated with RyR1 into functional SR Ca2+ release units.

Figure 3.

Recovery of skeletal-type EC coupling by coexpression of skeletal two-domain fragments. The confocal line-scan images show fluo-4 fluorescence across myotubes in response to a 50-ms depolarization from a holding potential of −40 mV. Traces immediately above each line scan show the time course of the fluorescence change in resting units (ΔF/F). (A) Ca2+ transients for I-II + III-IV at the indicated potentials. (B) Absence of Ca2+ transients for single fragments and Ca2+ transient for full-length α1S (WT) at +90 mV. (C) The average ΔF/F at the peak of the transient was plotted as a function of voltage for cells expressing I-II + III-IV (⋄, 15 cells), WT (♦, six cells), I-II (▵, eight cells), and III-IV (▿, 10 cells). Curves are a Boltzmann fit of the population mean ΔF/F-V curve. Parameters of the fit are ΔF/Fmax = 2.84, 2.78; V1/2 = 11.7, 11.02 mV; and k = 8.7, 11.03 mV for WT and for I-II + III-V, respectively. Line-scan images have a constant temporal dimension of 2.05 s (horizontal) and a variable spatial dimension (vertical) depending on the cell length. The cell dimension in the line scans was (in μm): 88 (A), 50 (B, I-II), 90 (B, III-IV), and 59 (B, full-length α1S, WT). (Bars = 500 ms and 1 ΔF/F.)

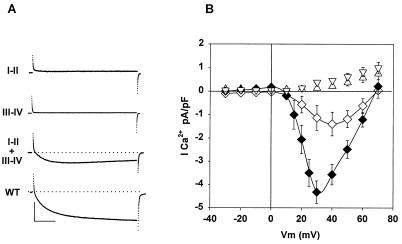

Because the skeletal DHPR has a separate function as an L-type Ca2+ channel, we investigated Ca2+ current expression. We detected dysgenic-type Ca2+ current in only 2 of 47 nontransfected myotubes. This current is a fast-activating low-density Ca2+ current that is far more frequent in mice of a different genetic background (18). Neither the I-II nor the III-IV domain expressed Ca2+ currents in 21 cells investigated from both groups (Fig. 4A). The α1A I-II domain also failed to express Ca2+ current, in agreement with previous results (11). Absence of Ca2+ current in cells expressing a single fragment was expected because all P-loops lining the Ca2+ pore have been implicated in Ca2+ permeation (19). Most cells coexpressing the two skeletal fragments did not have Ca2+ currents either (19 of 26 cells). However, a slow Ca2+ current was present in 7 of the 26 cells; these data are shown in Fig. 4. The Ca2+ current occasionally expressed by I-II plus III-IV had a lower than normal density, a ≈7-mV positive shift in half-activation potential, and a voltage dependence less steep than normal (Table 1). The lack of consistent expression of Ca2+ current by I-II and III-IV together could be due to the fragmentation of the II-III linker itself, which is critical for Ca2+ current expression (20), or to the absence of the region between T671 and V700, which is not present in either fragment. This region was removed to avoid the possibility of spurious (non-voltage-gated) stimulation of Ca2+ release by the I-II or III-IV fragment, as it occurs in vitro when SR vesicles are exposed to T671-L690 peptide (21). However, deleted residues K677 and K682 could be critical because these two residues are required for strong binding between the II-III linker and a RyR1 fragment in vitro (17). To investigate the latter possibility, we expressed a full-length α1S carrying a deletion of this region. The deletion mutant α1S Δ671–690 expressed a normal L-type Ca2+ current as well as a normal density of charge movements and EC coupling (Table 1). Hence this region is clearly nonessential for EC coupling, in agreement with recent results (22). However, the Ca2+ current expressed by the DHPR deletion mutant, like that recovered by the two DHPR fragments, had a positive shift in half-activation potential (Table 1). Therefore, it is possible that the absence of T671-V700 could be responsible for the shift in the voltage dependence of the Ca2+ current but not for the lack of stability of the Ca2+ channel formed by the I-II and III-IV fragments.

Figure 4.

Absence of Ca2+ currents in myotubes expressing individual DHPR fragments. (A) Absence or presence of whole-cell Ca2+ currents in myotubes expressing the indicated fragments. The depolarizing potential was +20 mV for 500 ms from a holding potential of −40 mV. (B) Current–voltage curves of the Ca2+ current of myotubes expressing I-II + III-IV (◊, 7 cells), full-length α1S (♦, 9 cells), I-II (▵, 11 cells), and III-IV (▿, 10 cells). The cell capacitance was (in pF) 154 (I-II), 186 (III-IV), 226 (I-II + III-IV), and 207 (full-length α1S, WT). (Calibration bars are 100 ms and 1 nA.)

Discussion

From the standpoint of charge movements and EC coupling, the fragmented α1S was as effective as the intact subunit. Because the DHPR β subunit is required to target the expressed Ca2+ channel to the cell surface (23), we further attempted to determine whether this subunit was necessary for recovery of charge movements by the fragmented α1S. We failed to detect specific charge movements or voltage-evoked Ca2+ transients when I-II and III-IV were expressed together or alone in knockout myotubes lacking β1a, the skeletal β isoform (13). Thus, the fragmented α1S, like the intact α1S, required other DHPR subunits for recovery of cell function. Furthermore, we found that the neuronal β4 or β1b subunit was essential for the expression of detectable charge movements by the neuronal α1A I-II fragment in dysgenic myotubes. Hence the skeletal β1a subunit expressed in the dysgenic myotube could not substitute for the neuronal counterparts in targeting the neuronal I-II fragment to the cell surface. β subunits bind strongly to the I-II linker of several tested α1 isoforms, including α1S (24), and to the I-II linker of the α1A I-II domain fragment (11). We thus propose that in the case of the skeletal fragments, the interaction of β1a and the I-II linker was sufficient to drive the I-II domain fragment to the cell surface when this domain was expressed alone and sufficient to drive the I-II/III-IV complex to the cell surface when both fragments were expressed in the same cell. Membrane targeting signals have also been reported in the C terminus region of the α1 subunit (25–27). In the present study, the C terminus region of α1S was insufficient to drive detectable amounts of the III-IV domain to the cell surface, as indicated by the absence of specific charge movements when this fragment was expressed in the absence of the I-II fragment. It is entirely conceivable that the membrane targeting signals in the β subunit and those in the C terminus of α1S influence each other in yet unknown ways. If this is the case, the higher density of charge movements expressed by I-II plus III-IV vs. I-II alone (5.4 ± 076 fC/pF vs. 3 ± 0.34 fC/pF, respectively) should be interpreted with caution, as differences in Qmax relate not only to the intrinsic properties of the whole complex vs. domains I and II, but also to the membrane target signals in the whole complex vs. those in the I-II domain alone. The contribution of targeting signals to the charge movement density as well as the potential formation of I-II/I-II dimers in the surface membrane remains to be further elucidated.

From the standpoint of the Ca2+ pore function of the DHPR, the fragmented α1S could not entirely substitute for its full-length counterpart. Earlier studies of the Na+ channel had shown that pore function was not compromised when the II-III linker or III-IV linker was cut and the two adjacent fragments were expressed together (28). The inability of the coexpressed I-II and III-IV domains to recover Ca2+ currents in a consistent manner could reflect an inability of the RyR1 to stimulate opening of the Ca2+ channel in the fragmented DHPR. A region in the II-III linker identified as CSk53 (α1S residues 720–765) was found to be essential for expression of skeletal-type EC coupling (29) and was later shown to be required for L-type Ca2+ current expression at control levels (20). In the present studies, CSk53 is present at the N terminus of the III-IV fragment, and its expression was immunodetected with SKI antibody against the central portion of CSk53 (not shown). The fact that in the fragmented α1S L-type Ca2+ current was recovered in only a few instances (7 of 26 cells) suggests that signal transmission from the RyR1 to the DHPR was unstable under these circumstances. However, it must be emphasized that recovery of EC coupling by the fragmented DHPR was consistently observed (15 of 15 cells).

The finding that the half-activation potential of charge movement was ≈20 mV more positive for the assembled four-domain DHPR than for the I-II fragment raises the possibility that interactions between the four domains may restrict the movement of S4 segments to individual domains. Those constraints may not be present in the I-II fragment if expressed in the absence of the III-IV fragment. There is ample evidence that the four internal domains of the Na+ channel play nonequivalent roles, with S4 segments of domains I and II moving faster than those of domains III and IV (30). Thus domain–domain interactions are likely to be critical for intramembrane charge movements in the assembled tetramer. The shift in half-activation potential could also reflect a change in electrostatic profile seen by the S4 charges in the two-domain fragment. This hypothesis is based on the fact that fluorescent reporters in the outer S4 region behave differently in the presence of pore blockers; thus the outermost section of the S4 segment in the K+ channel is thought to be in close proximity to the external pore region (31). The absence of a conducting pore in the I-II fragment could have caused an electrostatic change resulting in a more negative V1/2. Finally, the shift in charge movement half-activation potential could reflect the absence of an interaction between the I-II fragment and a DHPR subunit. Particularly relevant is α2-δ, because it is doubtful that the I-II fragment could form stable interactions with α2-δ (32). Other interactions missing in the two-domain proteins, especially those involving EC coupling proteins present in the T-tubule/SR junction (33), could possibly contribute to modifications of charge movements and remain to be investigated.

Truncated I-II domain proteins of Na+ and Ca2+ channels are ubiquitously expressed in brain and muscle tissues (8–11). The present results show unambiguously that I-II domains of Ca2+ channels do not produce inward Ca2+ current or support EC coupling. However, functional significance could be derived from the association of skeletal or neuronal I-II domains with corresponding Ca2+ channel β subunits. The two-domain proteins could serve as membrane-associated reservoirs of β subunits that could be donated to the full-length pore-forming Ca2+ channel under repetitive membrane activity (i.e., a voltage-dependent mechanism) or other conditions. The regulation of Ca2+ channels by homologous hemichannel fragments thus deserves full consideration.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AR 46448 and HL47053 and by predoctoral fellowships from the American Heart Association (to C.A.A. and J.A.). K.P.C. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Abbreviations

- DHPR

dihydropyridine receptor

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- RyR

ryanodine receptor

- EC

excitation–contraction

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Catterall W A. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:493–531. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bezanilla F. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:555–592. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rios E, Pizarro G. Physiol Rev. 1991;71:849–908. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.3.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang C L-H. Physiol Rev. 1988;68:1197–1247. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1988.68.4.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melzer W, Schneider M F, Simon B J, Szucs G. J Physiol (London) 1986;373:481–511. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rios E, Karhanek M, Ma J, Gonzalez A. J Gen Physiol. 1993;102:449–481. doi: 10.1085/jgp.102.3.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim A M, Vergara J L. J Physiol (London) 1998;511:509–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.509bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malouf N N, McMahon D K, Hainsworth C N, Kay B K. Neuron. 1992;8:899–906. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90204-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plummer N W, McBurney M W, Meisler M H. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24008–24015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.24008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wielowieyski P A, Wigle J T, Salih M, Hum P, Tuana B S. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(2):1398–1406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006868200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott V E S, Felix R, Arikkath J, Campbell K P. J Neurosci. 1998;18:641–647. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-02-00641.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beurg M, Sukhareva M, Strube C, Powers P A, Gregg R G, Coronado R. Biophys J. 1997;73:807–818. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78113-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beurg M, Sukhareva M, Ahern C A, Conklin M W, Perez-Reyes E, Powers P A, Gregg R G, Coronado R. Biophys J. 1999;76:1744–1756. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77336-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conklin M, Ahern C A, Vallejo P, Sorrentino V, Takeshima H, Coronado R. Biophys J. 2000;78:1777–1785. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76728-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beurg M, Ahern C A, Vallejo P, Powers P A, Gregg R G, Coronado R. Biophys J. 1999;77:2953–2967. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77128-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brawley R M, Hosey M M. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:18218–18223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leong P, MacLennan D H. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29958–29964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strube C, Beurg M, Sukhareva C, Ahern J A, Powell C, Powers P A, Gregg R G, Coronado R. Biophys J. 1998;75:207–217. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77507-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang J, Ellinor P T, Sather W A, Zhang J-F, Tsien R W. Nature (London) 1993;366:158–161. doi: 10.1038/366158a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grabner M, Dirksen R T, Beam K G. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21913–21919. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Hayek R, Antoniu B, Wang J, Hamilton S L, Ikemoto N. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22116–22118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Proenza C, Wilkens C M, Beam K G. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29935–29937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000464200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chien A J, Zhao X L, Shirokov R E, Puri T S, Chang C F, Sun D, Rios E, Hosey M M. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:30036–30044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.50.30036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pragnell M, De Waard M, Mori Y, Tanabe T, Snutch T P, Campbell K P. Nature (London) 1994;368:67–70. doi: 10.1038/368067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei X, Neely A, Lacerda A E, Olcese R, Stefani E, Perez-Reyez E, Birnbaumer L. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1635–1640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Proenza C, Wilkens C, Lorenzon N M, Beam K G. J Biol Chem. 2000;257:23169–23174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003389200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flucher B E, Kasielke N, Grabner M. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:467–477. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.2.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stühmer W, Conti F, Suzuki H, Wang X, Noda M, Yahagi N, Kubo H, Numa S. Nature (London) 1989;339:597–603. doi: 10.1038/339597a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakai J, Tanabe T, Konno T, Adams B, Beam K G. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24983–24986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.39.24983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cha A, Ruben P C, Goerge A L, Jr, Fujumoto E, Bezanilla F. Neuron. 1999;22:73–87. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80680-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cha A, Bezanilla F. J Gen Physiol. 1998;112:391–408. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.4.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gurnett C A, De Waard M, Campbell K P. Neuron. 1996;16:431–440. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McPherson P S, Campbell K P. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:13765–13768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]