ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Interventions to address obesity and weight loss maintenance among African Americans have yielded modest results. There is limited data on African Americans who have achieved successful long-term weight loss maintenance.

OBJECTIVE

To identify a large sample of African American adults who intentionally achieved clinically significant weight loss of 10 %; to describe weight-loss and maintenance efforts of African Americans through a cross-sectional survey; to determine the feasibility of establishing a registry of African American adults who have successfully lost weight.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS

African American volunteers from the United States ≥ 18 years of age were invited to complete a cross-sectional survey about weight, weight-loss, weight-loss maintenance or regain. Participants were invited to submit contact information to be maintained in a secure registry.

MAIN MEASURES

Percentage of participants who achieved long-term weight-loss maintenance reporting various dietary and physical activity strategies, motivations for and social-cognitive influences on weight loss and maintenance, current eating patterns, and self-monitoring practices compared to African Americans who lost weight but regained it. Participants also completed the Short International Physical Activity Questionnaire.

KEY RESULTS

Of 3,414 individuals screened, 1,280 were eligible and completed surveys. Ninety-percent were women. This descriptive analysis includes 1,110 women who lost weight through non-surgical means. Over 90 % of respondents had at least some college education. Twenty-eight percent of respondents were weight-loss maintainers. Maintainers lost an average of 24 % of their body weight and had maintained ≥ 10 % weight loss for an average of 5.1 years. Maintainers were more likely to limit their fat intake, eat breakfast most days of the week, avoid fast food restaurants, engage in moderate to high levels of physical activity, and use a scale to monitor their weight.

CONCLUSIONS

Influences and practices differ among educated African American women who maintain weight loss compared to those who regain it.

KEY WORDS: African-American, weight-loss maintenance, weight control registry, successful weight loss

The 2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Study estimates that in the United States 41 % of African American adults are obese versus 26 % of non-Hispanic whites.1 African Americans are also disproportionately affected by excess weight and diseases for which it is a risk factor.2,3 Although long-term weight loss maintenance and improved health are the ultimate goals of weight management programs, interventions to address obesity and promote long-term weight maintenance in African Americans have yielded modest results.3–6 The 1999–2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey estimates 15 % of African American adults who have ever been overweight have experienced long-term (≥ 1 year) weight loss maintenance of at least 10 %, versus 19 % of non-Hispanic whites.7 In clinical practice, a 10 % weight loss improves blood pressures, blood sugars, and lipids and is the clinically recommended goal for individuals trying to reduce weight.7–9

At present, there is scant evidence on highly successful weight-loss programs among African Americans. The National Weight Control Registry (NWCR) identified a large sample of individuals who were successful at long-term weight loss maintenance. Registrants had lost ≥ 13.6 kg (30 lb) and maintained that loss for at least 1 year. The study identified characteristics of successful maintainers and methods used to lose and maintain weight-loss. However, there were few African American participants in that cohort (N ≈ 74).10–15

Studies that provide new insights into successful weight-loss in African Americans are needed. Consequently, the objectives of the present study were 1) to identify a large sample of African American adults who intentionally achieved clinically significant weight loss of 10 %, 2) to understand weight-loss and maintenance in African Americans through a cross-sectional survey and 3) to determine the feasibility of establishing a registry of African American adults successful at weight loss.

METHODS

Study Design

This cross-sectional analysis used data from a survey designed to identify potential African American candidates for a weight control registry. Eligibility to complete the survey included self-identification as non-Hispanic Black or African American from a multiple choice list of standard NIH ethnic classifications, age ≥ 18 years, and intentional weight loss ≥ 10 % of body weight. Women who had been pregnant within a year of the study were ineligible.

Participant Recruitment

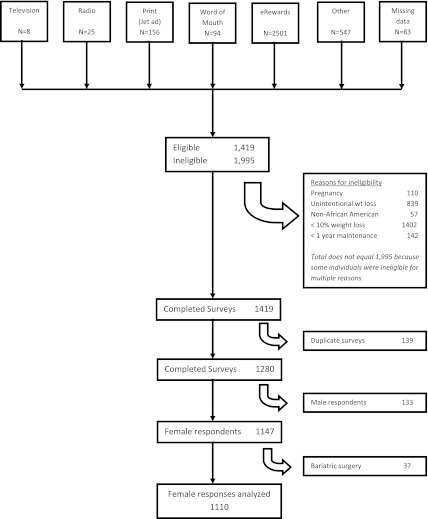

Participants were recruited between October 2006 and April 2009 through a variety of modalities aimed to attract a national sample of respondents. The flow of participants through recruitment, screening, survey completion and analysis is shown in Figure 1. Participants were asked their maximum body weight, weight achieved after greatest weight loss, current weight, and number of months between greatest weight loss and current weight.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of method of recruitment, screening, and survey completion.

Survey Design and Testing

Building on the reported descriptive data from the NWCR10 and focus group data from African Americans who had lost weight and either maintained the weight loss or regained it16, survey instruments were developed. One instrument was designed for individuals who had maintained ≥ 10 % weight loss for at least 1 year (75 questions). A second similar instrument was designed for individuals who lost ≥ 10 % of body weight and regained it (67 questions). The instruments were tested for acceptability and face validity using cognitive interviewing techniques to assess for tolerance of the survey length, clarity and relevance of the questions, and response error. Modifications were made to the instruments based on interview findings.

Measures

Categories of questions included in the surveys included initial weight loss methods, current weight maintenance methods or current reasons for weight regain, cultural influences on weight, and levels of physical activity using the Short International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). The IPAQ was selected because of its length and data validating its use in diverse populations.17 A formal dietary assessment tool was not used in this study because of economic limitations and participant time burden associated with the instrument. Theory-based socio-cognitive questions were also included; however, findings are outside of the scope of this descriptive report.

Both maintainer and regainer surveys asked participants whether they achieved initial weight loss through a change in diet, change in exercise, or both. Those who reported initial weight loss through dietary changes were asked about dietary techniques employed. Participants reporting physical activity changes were asked questions about preferred location for physical activity, preferred modes of physical activity, and with whom they exercised. All participants were asked to describe their motivations (triggers) for initial weight loss in their own words. Responses were classified as 5 differing trigger types (health concerns, upcoming event, self-esteem/appearance, physical discomfort, and other). Questions about current eating patterns and current levels of physical activity were included in both survey versions, and respondents were asked about weight self-monitoring methods as well.

Cultural themes that emerged from focus groups conducted to inform the development of the survey instruments included the role of faith in weight loss, female hair management during exercise, and social pressures to “not lose too much weight.” The survey instrument included questions addressing these issues.

There were limited differences between the two survey versions. Weight-loss maintainers were asked to indicate whether they were currently maintaining their weight with diet, exercise or both. Participants who had regained weight were asked to identify perceived reasons for regain (e.g. “I am unable to find time for exercise,” “I eat because of stress”).

Validation of Reported Weight Loss

Percentage of weight loss was based on self-reported weight and weight change. These methods have been used in other studies and are imperfect but of acceptable reliability.7,10,18,19 To further support accuracy of reported weight change by individuals identified as weight loss maintainers, participants were asked to identify a significant referent (e.g. physician, friend) who could verify their reported weight loss.

Statistical Analysis

Simple frequencies were calculated for respondent characteristics and responses to survey questions. Two-tailed t-tests and chi-square tests were used for between group comparisons using STATA software, and p-values were corrected using the Bonferroni method for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Respondent Characteristics

Three-thousand seventy-six individuals were screened for the study and 1,280 were eligible to participate. One hundred thirty-three surveys from men were excluded because of low response rate. An additional 37 surveys from women using bariatric surgery for weight loss were excluded because the focus of this analysis is on lifestyle changes. One thousand one hundred ten women are included in the analysis. Participants were divided into two main groups: those who maintained ≥ 10 % weight loss for at least a year (WLMs) and those who regained weight and did not maintain at least a 10 % loss (WLRs). Thirty percent of the sample of successful maintainers provided the name and contact information of a significant referent. Subjects who did not provide contact information of a referent other did not differ significantly from those who did in key demographic variables except they were less likely to report only a high school education (5.7 % vs. 11.5 % years, p < 0.05). Also, maintainers without a reference had lower BMI before weight loss and lost significantly less weight.

Characteristics of female subjects are shown in Table 1. Fifty-seven percent had a college degree or higher. Maintainers lost an average of 23 % of their body weight and had maintained ≥ 10 % weight loss for an average of 5.1 years. Twelve percent of maintainers had maintained the loss for ≥ 10 years.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Female Survey Respondents

| Maintainers | Regainers | Full Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean or % (S.D.) | Mean or % (S.D.) | p-value | Mean or % (S.D.) | N | |

| Age | 41.3 (11.1) | 41.1 (10.7) | 0.75 | 41.2 (10.8) | |

| Education | |||||

| <H.S. | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.73 | 0.5 | 6 |

| H.S. | 8.3 | 5.9 | 0.16 | 6.6 | 73 |

| Some College | 30.9 | 37.2 | 0.05 | 35.5 | 394 |

| College | 34.2 | 32.8 | 0.67 | 33.2 | 369 |

| Post College | 25.9 | 23.5 | 0.40 | 24.1 | 268 |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married | 36.7 | 35.9 | 0.82 | 36.1 | 400 |

| Single | 40.7 | 43.9 | 0.34 | 43.0 | 476 |

| Divorced | 20.0 | 18.3 | 0.53 | 18.8 | 208 |

| Widowed | 2.7 | 1.9 | 0.40 | 2.1 | 23 |

| Avg. weight before loss (kg) | 97.1 (22.3) | 89.8 (20.4) | <0.001* | 91.8 (21.1) | |

| Avg. weight loss (kg) | 22.9 (14.6) | 15.5 (8.0) | <0.001* | 17.5 (10.7) | |

| BMI before wt. loss | 35.5 (8.0) | 32.9 (7.1) | <0.001* | 33.6 (7.4) | |

| Change in BMI | 8.5 (5.4) | 6.0 (3.7) | <0.001* | 6.7 (4.4) | |

| BMI after wt. loss | 27.0 (6.2) | 27.0 (6.5) | 0.97 | 26.9 (6.4) | |

| Duration of wt. loss (mos.) | 61.2 (76.2) | -- | -- | ||

| Current BMI | 28.7 (6.3) | 34.8 (7.7) | <0.001* | 33.1 (7.8) | |

| Current weight (kg) | 78.4 (17.1) | 94.9 (22.6) | <0.001* | 90.4 (22.5) | |

| Total N | 301 | 809 | 1,110 | ||

T-tests or chi-square tests for significant differences between regainers and maintainers. P-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method.

* Statistically significant using the Bonferroni correction.

Methods Used for Weight Loss

Significantly more WLMs reported losing weight “on their own” (dietary changes and/or exercise without medications) than WLRs (65 % compared to 51 %, p < 0.001). Only 19 % of subjects in both groups used a formal program (e.g., Weight Watchers, Jenny Craig) for initial weight loss.

Seventy-three percent of maintainers and 62 % of regainers reported achieving successful weight loss through both dietary and physical activity changes. The prevalence of maintainers and regainers who changed their diets and engaged in various dietary activities is listed in Table 2. Similarly, for those who exercised during weight loss, physical activity preferences and strategies for both groups are reported in Table 3.

Table 2.

Dietary Changes During Initial Weight Loss and Weight Loss Maintenance

| Maintainers | Regainers | Full Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Maintenance* | Initial | Initial | ||

| (N) or % | (N) or % | (N) or % | p-value† | (N) or % | |

| Changed Diet (N) | (271) | (255) | (651) | (922) | |

| Did Not Change Diet (N) | (30) | (46) | (158) | (188) | |

| Limited amount of all foods | 73.1 | 69.8 | 68.4 | 0.16 | 69.7 |

| Decreased portion size | 68.6 | 67.1 | 63.6 | 0.14 | 65.1 |

| Limited certain food types | 76.0 | 74.1 | 67.4 | 0.009 | 70.0 |

| Limited carbohydrates | 35.8 | 38.4 | 28.7 | 0.03 | 30.8 |

| Counted Calories | 33.2 | 28.2 | 26.4 | 0.04 | 28.4 |

| Limited amount of fat | 46.9 | 45.1 | 34.3 | <0.001* | 38.0 |

| Counted fat grams | 15.9 | 14.5 | 12.4 | 0.16 | 13.5 |

| Used exchange/points diet | 9.6 | 3.9 | 15.2 | 0.02 | 13.6 |

| Liquid formula diet | 6.3 | 4.3 | 8.5 | 0.26 | 7.8 |

| Meal replacement program | 5.2 | 5.1 | 5.4 | 0.90 | 5.3 |

| Ate one or two types of food | 3.3 | 2.0 | 4.3 | 0.49 | 4.0 |

| Drank more water | 78.6 | 80.0 | 65.8 | <0.001* | 69.5 |

| Ate last meal of the day before 7 pm | 43.2 | 31.0 | 35.2 | 0.02 | 37.5 |

| Total N | (301) | (301) | (809) | (1,110) | |

Maintainers were asked whether they were currently watching their diet to maintain their weight. Percentages are for all maintainers who reported they were watching their diet.

* Statistically significant using the Bonferroni correction.

†Chi-square tests for significant differences between Maintainers (initial weight loss) and Regainers. P-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method.

Note: Respondents selected all applicable categories so responses do not total to 100 %. Of those who changed their diet, 78 % changed both diet and exercise and 22 % changed only diet.

Table 3.

Physical Activity Strategies During Initial Weight Loss and Maintenance

| Maintainers | Regainers | Full Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Maintenance | Initial | Initial | ||

| (N) or % | (N) or % | (N) or % | p-value* | (N) or % | |

| Exercised (N) | (237) | (209) | (599) | (836) | |

| Did not exercise (N) | (64) | (92) | (210) | (274) | |

| Type of exercise | |||||

| Walking | 76.4 | 79.9 | 72.1 | 0.21 | 73.3 |

| Running/Jogging | 27.4 | 35.9 | 26.2 | 0.72 | 26.6 |

| Aerobic dancing | 38.0 | 38.3 | 42.7 | 0.21 | 41.4 |

| Other dancing | 17.3 | 22.0 | 14.9 | 0.38 | 15.6 |

| Playing sports | 4.6 | 2.4 | 6.7 | 0.27 | 6.1 |

| Swimming | 8.9 | 3.8 | 5.8 | 0.12 | 6.7 |

| Bicycling | 11.4 | 11.0 | 9.5 | 0.42 | 10.1 |

| Spin Class | 3.0 | 8.1 | 3.2 | 0.87 | 3.1 |

| Yoga/Pilates | 9.7 | 18.2 | 7.2 | 0.22 | 7.9 |

| Lifting weights | 32.5 | 48.8 | 25.7 | 0.05 | 27.6 |

| Doing extra house/yard work | 21.9 | 26.8 | 12.5 | < 0.001* | 15.2 |

| Other | 11.0 | 7.8 | 8.9 | 0.34 | 9.5 |

| Where did you exercise? | |||||

| At home | 53.2 | 61.2 | 46.4 | 0.08 | 48.3 |

| At work (walking, exercise) | 21.9 | 19.1 | 18.4 | 0.24 | 19.4 |

| At work (part of my job) | 4.2 | 2.9 | 3.7 | 0.71 | 3.8 |

| At a fitness center/gym | 43.0 | 45.9 | 44.6 | 0.69 | 44.1 |

| At the park (on own) | 35.0 | 34.9 | 31.6 | 0.33 | 32.5 |

| At the park/gym (team sports) | 5.9 | 0.5 | 4.0 | 0.23 | 4.6 |

| Outside in my neighborhood | 23.2 | 26.8 | 19.9 | 0.28 | 20.8 |

| Other | 7.6 | 4.6 | 7.9 | 0.90 | 7.8 |

| Who did you exercise with? | |||||

| No one | 68.5 | 70.3 | 57.1 | 0.002 | 60.3 |

| Exercise Group/Class | 11.9 | 11.5 | 15.2 | 0.22 | 14.3 |

| Friend | 11.1 | 6.7 | 15.2 | 0.12 | 14.0 |

| Family | 5.1 | 8.1 | 6.8 | 0.35 | 6.4 |

| Team | 1.3 | 0.0 | 2.8 | 0.18 | 2.4 |

| Other | 2.1 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 0.56 | 2.6 |

| N | (301) | (301) | (809) | (1,100) | |

Maintainers were asked whether they were currently exercising to maintain their weight. Percentages are for all maintainers who reported they were currently exercising.

* Statistically significant using the Bonferroni correction.

†Chi-square tests for significant differences between Maintainers (initial weight loss) and Regainers. P-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method.

Note: Respondents selected all applicable categories so responses do not total to 100 %. Of those who exercised during weight loss, 14 % only exercised and 86 % changed diet and exercise.

Approximately 90 % of respondents reported a motivating trigger resulted in weight loss. Significantly more maintainers than regainers identified health concerns as their trigger to lose weight (32.4 % compared to 22.7 %, p ≤ 0.001).

Weight Maintenance and Weight Regain

Seventeen percent of maintainers reported watching only their diet to help maintain weight, and 6 % reported only exercising to keep weight off. Seventy-three percent reported using both strategies. WLMs reported similar dietary and exercise practices for weight loss maintenance as they did for initial weight loss (Table 2). WLRs were asked to identify reasons for weight regain. Eating due to stress (53 %), being unable to find time for exercise (47 %), and feeling lazy or unmotivated (52 %) were the most-cited reasons for regaining weight.

Current eating patterns for WLMs and WLRs are significantly different as they relate to eating breakfast and eating outside of the home. Table 4 reveals that maintainers are more likely to eat breakfast and to avoid fast food when compared to regainers.

Table 4.

Current Eating, Exercise, and Self-Monitoring Habits

| Regainers | Maintainers | p-value | Full Sample | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eats breakfast 4+ Days per Week | 62.4 | 81.8 | <0.001* | 67.0 |

| How many times per day do you eat? | ||||

| 1 time a day | 3.5 | 1.7 | 0.12 | 3.0 |

| 2-3 times a day | 50.0 | 40.0 | 0.003 | 47.3 |

| 4-5 times a day | 38.1 | 48.5 | 0.002 | 40.9 |

| 6-7 times a day | 7.8 | 9.6 | 0.32 | 8.3 |

| 8 or more times a day | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.56 | 0.5 |

| How many times per week do you eat fast food? | ||||

| Less than 1 time per week | 34.4 | 58.1 | <0.001* | 40.9 |

| 1-2 times per week | 36.9 | 31.2 | 0.08 | 35.4 |

| 3-4 times per week | 21.1 | 9.0 | <0.001* | 17.8 |

| 4+ times per week | 7.6 | 1.7 | <0.001* | 6.0 |

| How many times per week do you eat at a non-fast food restaurant? | ||||

| Less than 1 time per week | 71.0 | 58.1 | <0.001* | 67.4 |

| 1-2 times per week | 8.8 | 29.2 | <0.001* | 14.4 |

| 3-4 times per week | 13.9 | 9.0 | 0.03 | 12.6 |

| 4+ timesper week | 6.4 | 3.7 | 0.08 | 5.6 |

| IPAQ | ||||

| Low Physical Activity | 45.4 | 27.2 | <0.001* | 40.5 |

| Moderate Physical Activity | 22.9 | 17.9 | 0.08 | 21.5 |

| High Physical Activity | 31.8 | 54.8 | <0.001* | 38.0 |

| How often do you weigh yourself? | ||||

| At least once per day | 11.3 | 16.6 | 0.02 | 12.7 |

| At least once per week | 23.6 | 31.9 | 0.005 | 25.8 |

| At least once per month | 17.9 | 21.3 | 0.20 | 18.8 |

| Less than once per month | 47.3 | 30.2 | <0.001* | 42.6 |

| What lets you know that you’re gaining weight? | ||||

| The scale | 13.7 | 26.7 | <0.001* | 17.2 |

| The fit of my clothes | 81.6 | 70.0 | <0.001* | 78.5 |

| Comments from others | 2.4 | 1.7 | 0.49 | 2.2 |

| Other | 2.4 | 1.7 | 0.49 | 2.2 |

| N | 809 | 301 | 1,110 |

Chi-square tests for significant differences between maintainers (initial weight loss) and Regainers. P-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method.

* Statistically significant using the Bonferroni correction.

Based on responses to the Short IPAQ, WLMs and WLRs scored very differently regarding current levels of physical activity (χ2 = 50.9, p < 0.001). Maintainers were most likely to score in the “High” activity category: 55 % compared to just 32 % of regainers. Forty-five percent of regainers were in the “Low,” or inactive, category.

Current weight self-monitoring practices were reported by both WLMs and WLRs (Table 5). Regainers were more likely to report weighing themselves “less than once a month” (47.3 % vs. 30.2 %, p < 0.001). They were also more likely to recognize weight gain due to the fit of their clothes than maintainers (81.6 % vs. 70 %, p < 0.001).

Table 5.

Clinical Relevance and Implications

| Maintainers were more likely than regainers to … | Practice Implications |

|---|---|

| Identify a health concern as their reason for weight loss (32.4 % vs. 22.7 %, p < 0.001) | Use the clinical encounter and/or a health issue as a teachable moment to encourage sustained weight loss |

| Limit fat intake (46.9 % vs. 34.3 %, p < 0.001) | Provide targeted counseling specifically on reduction of fat intake |

| Consume fast food less than once a week (58.1 % vs. 34.4 %, p < 0.001) | Strongly discourage eating fast food |

| Weigh themselves at least once a month (70.0 % vs. 52.5 %, p < 0.001) | Encourage self-monitoring of weight by use of a scale at least monthly |

Influence of Cultural Factors

All participants were asked about the role of faith (religion) in their initial weight loss efforts, successful maintenance, or unsuccessful maintenance efforts. A majority (57 %) of maintainers and regainers reported that faith had either a limited or important role in their initial weight loss, with more maintainers choosing “important role” (42 % compared to 27 %, (χ2 = 22.3, p < 0.001). Maintainers were also more likely to say that faith was important in maintaining their weight (43 %), compared to 23 % of regainers who said faith was important in trying to keep off the weight.

Women subjects in both groups were asked about their current hairstyle which has been shown to influence participation in physical activity.4,20 Female WLMs were no more likely to report a natural hairstyle or wig than WLRs (23 % compared to 18 %, (χ2 = 2.14, p = 0.144). The majority of women in both groups (55 % and 56 %, respectively) reported they wore a relaxed hairstyle. Contrary to expectations, women in each hairstyle category scored identically on the IPAQ.

Actions related to “not losing too much weight” were evident in the sample. Weight loss maintainers and regainers reported some intentional weight regain (12 % compared to 8 %, (χ2 = 4.2, p < 0.05). Three percent of respondents reported gaining some weight back because they thought they looked too skinny.

Registry

Seventy-three percent of sample of questionnaire respondents included in this analysis agreed to participate in an African American Weight Control Registry and provided contact information to be maintained in a secure database. Of the 1,110 questionnaire respondents, 59 % of maintainers and 78 % of regainers became a part of the registry.

Registrants were more likely to have a larger starting BMI (34.1 kg/m2 vs. 32.3 kg/m2, p < 0.001) than non-registrants. Non-registrants were more likely to report using only exercise for weight loss (14.7 % vs. 8.8 %, p < 0.05) and to losing weight on their own without a formal program (60.0 % vs. 52.8 %, p < 0.05) than registrants.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest sample of African Americans successful at long-term weight loss maintenance. Although weight analysis of the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study did identify 115 African Americans who had lost ≥ 5 % of body weight and maintained at least 75 % of that loss for 5 years, it did not assess intentionality of weight loss and provided a limited assessment of factors associated with long-term weight loss success (African American ethnicity, moderate physical activity, and limited consumption of sugar sweetened beverages).21

Like NWCR members, African American women identified in this study were extremely successful at losing weight. Of note, most achieved initial weight loss success “on their own” and without the use of formal, fee-based, weight loss programs. Higher starting BMIs were associated with larger weight losses and maintenance in this sample. This has not been described in other studies, and it is unclear whether heavier individuals, in fact, have more success or whether heavy individuals in this voluntary sample were more likely to participate and share their weight loss success. Controlling for starting BMI did not, however, change the significance of comparisons between WLM and WLR.

The three cultural themes explored in the surveys yielded interesting results that warrant further research. Religious faith was identified as playing an important role in weight loss and maintenance more commonly in WLM than WLR. Several faith-based weight loss studies do indicate some successes when spiritual beliefs are tied to practical life-style changes;22–24 however, the individual operationalization of faith in unstructured weight loss and maintenance efforts needs further delineation before its role is fully understood.

Although hair management during exercise may not be unique to African Americans, it was identified as particularly relevant when focus groups of African American maintainers were asked about their weight loss experiences.16 A few studies acknowledge hair style maintenance as significant for African American women who engage in physical activity.4,20 African American women wear a variety of hairstyles: those considered easy to manage on a daily basis and after exercise (afro, natural, locks, braids, and wig) and one that is traditionally considered more time consuming to manage and more negatively affected by sweating (relaxed). Although this study did not demonstrate a clear difference in reported physical activity levels among women with natural versus relaxed hair styling, the role of this qualitatively endorsed influence on physical activity needs further exploration.

The fact that 10 % of WLM and WLR intentionally regained some of the weight they loss is an interesting and previously unreported phenomenon. Older research suggests lower desire for thinness in African Americans compared to Caucasians,25,26 and future research can help in the socio-historical understanding of the perceived undesirability of losing “too much” weight.

Several findings from this study are relevant for clinicians treating similar patient populations. Practice implications are listed in Table 5. The cultural considerations described above suggest there are additional factors that influence successful weight loss and maintenance in this group; however, further study is necessary before recommendations can be made on how best to counsel around these issues in clinical settings.

Information from individuals who agreed to be a part of an African American Weight Control Registry is maintained in a secure database. Current and future registrants will be tracked using follow-up surveys to assess weight management over time and to understand nutrient consumption as well as behavioral and social strategies that were not assessed in this initial study. The ability to continue to gather data on individuals who have successfully lost and maintained weight will add significantly to the understanding of long-term weight loss in this high risk population.

Although this study provides the largest sample of African American women intentionally successful at clinically significant long-term weight loss, there are limitations to its interpretation and areas for improvement in future studies. Participants are self-selected volunteers. This introduces voluntary response bias and limits its generalizability. Only ten percent of respondents to this survey were men. Twenty-four percent of NWCR registrants were men; however, < 1 % were African American men.15 It is unclear whether the topic of weight management is uninteresting to men, but challenges in recruitment of African American men into biomedical research have been well documented.27–30

The study sample is very educated when compared to randomly-selected national samples of African American women. In NHANES 1999–2006, 49 % of participants had at least some college education31 compared to 91 % in this sample, thus potentially limiting its applicability to the larger African American population. Although a variety of recruitment methods were employed, most survey respondents were recruited through eRewards which is an online service. There was likely an oversampling of individuals with internet access which may explain the high educational level of respondents. Lower socioeconomic status is linked to increased prevalence of obesity, so successful maintainers from this group need to be identified as well.

The IPAQ short form was used to assess physical activity levels among respondents. Recent research suggests it may not be the most ideal physical activity assessment tool for this population.32 Lastly, the cross-sectional study design limits the conclusions that can be drawn about the causal effects of various historical and current behaviors reported by respondents and their weight maintenance or regain.

This study provides evidence that educated African American women can and do achieve significant long-term weight loss. Many strategies are consistent with those of NWCR members. There are significant differences in motivations and practices between African American women who lose weight and keep it off and individuals who lose weight and regain it. Future studies will strive to recruit a more inclusive sample of African Americans and to uncover critical factors that predict weight loss maintenance across socioeconomic strata and how they are operationalized. Greater understanding will inform the development of weight-loss interventions for this disproportionately affected group.

Acknowledgement

Funding Support

Implementation of this study was funded by an NIDDK Career Development award for A. S. Barnes (K08 DK064898). Data analysis was supported by the Health Economics Program at the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy at Rice University.

Financial Disclosures

The authors have no financial disclosures related to this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the do not have conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2010. Prevalence and Trends Data. Overweight and Obesity (BMI). Available at: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/BRFSS/page.asp?cat=OB&yr=2010&state=UB#OB. Accessed March 13, 2012.

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. JAMA. 2006;295(13):1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin PD, Dutton GR, Rhode PC, Horswell RL, Ryan DH, Brantley PJ. Weight loss maintenance following a primary care intervention for low-income minority women. Obesity. 2008;16(11):2462–2467. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stolley MR, Fitzgibbon ML, Schiffer L, et al. Obesity reduction black intervention trial (ORBIT): six-month results. Obesity. 2009;17(1):100–106. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Schiffer L, Sharp LK, Singh V, Dyer A. Obesity reduction black intervention trial (ORBIT): 18-month results. Obesity. 2010;18(12):2317–2325. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, et al. Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss: the weight loss maintenance randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(10):1139–1148. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kraschnewski JL, Boan J, Esposito J, et al. Long-term weight loss maintenance in the United States. Int J Obes. 2009;34(11):1644–1654. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults--The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998;6 Suppl 2:51S-209S. [PubMed]

- 9.Wing RR, Phelan S. Long-term weight loss maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(1 Suppl):222S–225S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.222S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klem ML, Wing RR, McGuire MT, Seagle HM, Hill JO. A descriptive study of individuals successful at long-term maintenance of substantial weight loss. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66(2):239–246. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butryn ML, Phelan S, Hill JO, Wing RR. Consistent self-monitoring of weight: a key component of successful weight loss maintenance. Obesity. 2007;15(12):3091–3096. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Catenacci VA, Grunwald GK, Ingebrigtsen JP, et al. Physical Activity Patterns Using Accelerometry in the National Weight Control Registry. Obesity (Silver Spring). Oct 28 2010: 1163–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Raynor DA, Phelan S, Hill JO, Wing RR. Television viewing and long-term weight maintenance: results from the National Weight Control Registry. Obesity. 2006;14(10):1816–1824. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wyatt HR, Grunwald GK, Mosca CL, Klem ML, Wing RR, Hill JO. Long-term weight loss and breakfast in subjects in the National Weight Control Registry. Obes Res. 2002;10(2):78–82. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Catenacci VA, Ogden LG, Stuht J, et al. Physical activity patterns in the National Weight Control Registry. Obesity. 2008;16(1):153–161. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnes AS, Goodrick GK, Pavlik V, Markesino J, Laws DY, Taylor WC. Weight loss maintenance in African-American women: focus group results and questionnaire development. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(7):915–922. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0195-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–1395. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casey VA, Dwyer JT, Berkey CS, Coleman KA, Gardner J, Valadian I. Long-term memory of body weight and past weight satisfaction: a longitudinal follow-up study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53(6):1493–1498. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/53.6.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevens J, Keil JE, Waid LR, Gazes PC. Accuracy of current, 4-year, and 28-year self-reported body weight in an elderly population. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(6):1156–1163. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Railey MT. Parameters of obesity in African-American women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000;92(10):481–484. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phelan S, Wing RR, Loria CM, Kim Y, Lewis CE. Prevalence and predictors of weight-loss maintenance in a biracial cohort: results from the coronary artery risk development in young adults study. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(6):546–554. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim KH, Linnan L, Campbell MK, Brooks C, Koenig HG, Wiesen C. The WORD (wholeness, oneness, righteousness, deliverance): a faith-based weight-loss program utilizing a community-based participatory research approach. Health Educ Behav. 2008;35(5):634–650. doi: 10.1177/1090198106291985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Ganschow P, et al. Results of a faith-based weight loss intervention for black women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(10):1393–1402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yanek LR, Becker DM, Moy TF, Gittelsohn J, Koffman DM. Project Joy: faith based cardiovascular health promotion for African American women. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(Suppl 1):68–81. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becker DM, Yanek LR, Koffman DM, Bronner YC. Body image preferences among urban African Americans and whites from low income communities. Ethn Dis. 1999;9(3):377–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powell AD, Kahn AS. Racial differences in women's desires to be thin. Int J Eat Disord. 1995;17(2):191–195. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(199503)17:2<191::AID-EAT2260170213>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Byrd GS, Edwards CL, Kelkar VA, et al. Recruiting intergenerational African American males for biomedical research studies: a major research challenge. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(6):480–487. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30361-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas S, St. George D. Distrust, race, and research. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(21):2458–2463. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK. Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woods VD, Montgomery SB, Herring RP. Recruiting Black/African American men for research on prostate cancer prevention. Cancer. 2004;100(5):1017–1025. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu Y. Educational differences in obesity in the United States: a closer look at the trends. Obesity (Silver Spring)April 2012;20:904–908. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Wolin KY, Heil DP, Askew S, Matthews CE, Bennett GG. Validation of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short among blacks. J Phys Act Health. 2008;5(5):746–760. doi: 10.1123/jpah.5.5.746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]