Abstract

Background

Aflibercept is a novel decoy receptor that efficiently neutralizes circulating vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). A pediatric phase 1 trial was performed to define the dose limiting toxicities (DLT), maximum tolerated dose (MTD) and pharmacokinetics (PK) of aflibercept.

Methods

Cohorts of 3–6 children with refractory solid tumors received aflibercept intravenously over 60 minutes every 14 days, at 2.0, 2.5 or 3.0 mg/kg/dose. PK sampling and analysis of peripheral blood biomarkers were performed with the initial dose.

Results

21 eligible patients were enrolled; 18 were fully evaluable for toxicity. One of 6 patients receiving 2.0 mg/kg/dose developed dose-limiting intra-tumoral hemorrhage and 2 of 6 receiving 3.0 mg/kg/dose developed either dose-limiting tumor pain or tissue necrosis. None of the 6 patients receiving 2.5 mg/kg/dose developed DLT, defining this as the MTD. The most common non-dose limiting toxicities were hypertension and fatigue. Three patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatoblastoma and clear cell sarcoma had stable disease for >13 weeks. At the MTD, the ratio of free to bound aflibercept serum concentration was 2.10 on day 8, but only 0.44 by day 15. A rapid decrease in VEGF (p<0.05) and increase in PlGF (p<0.05) from baseline was observed in response to aflibercept by day 2.

Conclusion

The aflibercept MTD in children of 2.5 mg/kg/dose every 14 days is lower that the adult recommended dose of 4.0 mg/kg. This dose achieves, but does not sustain, free aflibercept concentrations in excess of bound. Tumor pain and hemorrhage may be evidence of anti-tumor activity, but were dose-limiting.

Keywords: Aflibercept, pediatric, pharmacokinetics, angiogenesis, VEGF

INTRODUCTION

Extensive tumor vascularity has been linked to advanced stage and poor prognosis in both adult and pediatric malignancy. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) delivers a powerful mitogenic and survival stimulus to tumor vessel endothelium and enhances vascular permeability, promoting both cancer growth and metastasis.1 To date, several drugs targeting VEGF have been shown to benefit adult cancer patients.2 Aflibercept (VEGF Trap; Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Tarrytown, NY, and Sanofi-Aventis Oncology, Bridgewater, NJ) is a fully human, composite decoy receptor, in which the extracellular domains of VEGF receptors-1 and -2 (VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2) are fused to an Fc segment of IgG1. Aflibercept sequesters VEGF, VEGF-B, and placental growth factor (PlGF) with extraordinarily high affinity (VEGF165 Kd= 1 pM).3 Aflibercept caused striking inhibition of tumor angiogenesis, resulting in regression of established tumors, in orthotopic xenografts derived from a pediatric renal cancer harboring the EWS/FLI translocation as well as from a hepatoblastoma.4–5 In neuroblastoma models, aflibercept substantially decreased co-opted vessels.6

The adult recommended phase 2 dose of aflibercept administered as a single agent is 4.0 mg/kg intravenously every 2 weeks, based on toxicity, pharmacokinetic (PK) profile, biomarker analysis and anti-tumor activity. Proteinuria and rectal ulceration, occurring at 7.0 mg/kg, were the dose limiting toxicities (DLT) in adults with refractory solid tumors.7 Common adverse events associated with aflibercept administration included fatigue (63.8%), dysphonia (46.8%), hypertension (38.3%), nausea (36.2%), vomiting (27.7) and proteinuria (10.6%). Objective tumor responses were observed at doses of 3.0 mg/kg and higher. At doses levels of 2.0 mg/kg and higher, free aflibercept concentrations increased proportionately with dose, but bound aflibercept concentrations appeared to plateau, indicating maximal ligand sequestration had been achieved. Recently, the addition of aflibercept has been shown to increase overall survival in patients receiving second-line irinotecan/5-FU (FOLFIRI) chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer,8 and a substantial tumor response rate to docetaxel plus aflibercept has been demonstrated in patients with recurrent ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer.9

Between May 2008 and October 2009, the Phase I consortium of the Children’s Oncology Group conducted a trial in pediatric patients with refractory solid tumors. Primary aims included estimating the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of aflibercept administered intravenously as monotherapy every 14 days, describing dose-limiting and other toxicities, and evaluating the ability to achieve and sustain free in excess of bound aflibercept levels over the duration of the dosing interval.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Participants

Patients 1 to 21 years of age with solid or CNS malignancy and measurable or evaluable disease, and for whom no curative therapy existed were eligible. Following episodes of dose-limiting intra-tumoral hemorrhage and tumor rupture in 2 of the initial 14 patients, patients with primary or metastatic CNS tumors and/or pleural based lesions were excluded from subsequent enrollment (Amendment 4, April 2009). Patients were required to have a Karnofsky (age > 16 years) or Lansky (age ≤ 16 years) performance score ≥ 50 and to have recovered from prior therapy. Patients were also required to have adequate baseline renal, hepatic and hematologic function, as well as a blood pressure within the 95th percentile for age, height and gender10 and not be receiving anti-hypertensive medication. Exclusion criteria included: patients with clinically significant cardiovascular disease (e.g. pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, or other thromboembolic event within past 6 months); prior bleeding event, current bleeding diathesis or treatment with anti-platelet or anti-thrombotic agents; recent or planned major surgery, evidence of chronically impaired wound healing, abdominal fistula, gastrointestinal perforation, or intra-abdominal abscess within 28 days of treatment; pregnancy or lactation; uncontrolled infection; and concurrent use of other investigational or anticancer agents.

The Institutional Review Board of each participating site approved this trial. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients, including assent from minor subjects according to institutional guidelines.

Drug Administration and Study Design

Aflibercept was supplied by Sanofi-Aventis Pharmaceuticals and distributed by the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (NCI, Bethesda, MD) in 100 mg (4 mL) or 200 mg (8 mL) vials to be further diluted in 0.9% sodium chloride or 5% dextrose to a final concentration between 0.6 mg/mL and 8 mg/mL. Aflibercept was administered intravenously over 60 minutes every 2 weeks (1 cycle). Cycles could be repeated every 14 days for up to 24 months in patients without disease progression or DLT. For the purposes of data reporting, one course encompassed 2 cycles.

The starting dose was 2.0 mg/kg/dose, the lowest dose at which complete VEGF ligand sequestration could be achieved in adults. Planned dose escalations were to occur in increments of 1.0 mg/kg/dose. No intra-patient dose escalation was allowed. A conventional 3 by 3, phase 1 dose escalation scheme was used wherein the MTD was exceeded if either 2/3 or 2/6 subjects encountered DLT. When this occurred at the second dose level (3.0 mg/kg), the study plan was modified to investigate an intermediate dose of 2.5 mg/kg (Amendment 4).

Toxicity Assessment and Disease Evaluations

Toxicity monitoring included physical examination with blood pressure measurement, complete blood counts, and serum chemistries, including electrolytes, creatinine, ALT, bilirubin, total protein and albumin (weekly during cycles 1 and 2, then prior to each cycle). Prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time (PTT) were also evaluated once prior to each cycle. Clinical and laboratory adverse events were graded according to the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 3.11 Gender and height adjusted norms were used to assess blood pressure elevation above the 95th percentile for age.10 The study utilized a previously described algorithm for the determination and management of drug related hypertension.12 Tibial radiographs were performed in patients who had not yet achieved adult height. Response was evaluated using either Response Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) or 2-dimensional measurement for CNS tumors with imaging at baseline, the end of cycle 2, and then every 4 cycles.

Definition of Dose-Limiting Toxicity (DLT) and Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD)

Hematologic DLT was defined as: Grade 4 neutropenia or Grade 4 thrombocytopenia of > 7 days duration; Grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia that required transfusion therapy more than twice during a cycle; or myelosuppression that caused delay of ≥ 14 days between cycles. Non-hematologic DLTs included any grade 4 toxicity; any grade 3 toxicity with exceptions of nausea and vomiting of < 3 days duration, ALT or AST elevations that recovered to grade ≤ 1 by the time of the next cycle, fever or infection < 5 days, electrolyte abnormalities responsive to oral supplementation and grade 3 pain adequately controlled with narcotic analgesics; Grade 2 proteinuria (> 2g/24 hr) not resolving to eligibility range within 4 weeks, and medically significant grade 2 toxicity that persisted for ≥ 7 days and required treatment interruption. Dose-limiting hypertension was specifically defined as any grade 4 hypertension, confirmed systolic or diastolic blood pressure > 25 mm Hg above the ULN, or an elevated blood pressure not controlled by anti-hypertensive medication within 14 days.12 Patients with DLT that resolved within 7 days and continued to meet eligibility parameters were eligible for one dose reduction. Aflibercept was permanently discontinued for recurrent DLT, grade 2 arterial thromboembolic events, any requirement for systemic anticoagulation, thrombotic microangiopathy, bleeding requiring acute medical management, transfusion or hospitalization, reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy, intestinal perforation and fistula formation regardless of anatomic location.

Only DLT during course 1 (cycles 1 and 2) were considered for dose escalation and determination of the MTD. Patients were considered fully evaluable for toxicity if they either developed a DLT or received at least 85% of the prescribed dose over this interval. Patients not meeting these criteria were replaced. The MTD was defined as the dose level immediately below the dose level at which fewer than one-third of patients experienced a DLT.

Pharmacokinetics (PK) and Pharmacodynamics (PD)

Mandatory plasma aflibercept levels were measured prior to drug administration on day 1 and day 8 (range 7–9) of cycle 1, and prior to day 1 of cycles 2 and 5, to assess ability to achieve and maintain a target therapeutic dose, defined as free in excess of bound aflibercept. Optional PK sampling was obtained at 1 and 24 hours, and 3–5 days post infusion in cycle 1. Blood was collected from a site distant from the infusion (if < 6 days) into a Hemogard, 4.5 mL tube containing citrate buffer, theophylline adenosine and dipyridamole (B–D Cat #367947) to prevent platelet lysis during plasma sample preparation. Samples were centrifuged at approximately 1200 × g for 15 minutes at room temperature within 1 hour and the plasma stored frozen at −20°C. Free aflibercept concentration in plasma was measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with microplates coated with human VEGF, whereas bound VEGF:aflibercept complex concentration was measured using plates coated with anti-VEGF antibody. Serum samples at baseline and prior to infusion every 8 weeks were also obtained to measure anti-aflibercept antibody testing by ELISA (Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc; Tarrytown, NY).

Aflibercept plasma concentration-time data were fit by standard non-compartmental methods using WINNONLIN Pro version 4.1 (Pharsight). The terminal elimination rate constant was determined by least-squares regression of the serum concentration-time data for the last 2 to 3 time-points.

Voluntary PD samples for plasma and cellular markers of angiogenesis were collected in EDTA tubes, before the dose on day 1 and on day 2 of cycle 1, and just prior to cycle 2. Plasma was immediately separated by centrifugation at 4°C. Plasma angiogenic cytokines [VEGF, soluble VEGFR-1 (sVEGFR-1) and soluble VEGFR-2 (sVEGR-2), and PlGF] were performed using commercially available ELISA kits. Blood for total, progenitor, and apoptotic circulating endothelial cells was shipped on ice to a central lab and analyzed within 24 hours of collection according to previously described four-color flow cytometry methods.13–14 Changes in biomarkers of angiogenesis obtained at baseline, day 2 and at the end of cycle 1 were assessed using the paired t-test for normally distributed data and the Wilcoxon signed rank test for non-normal data.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Of the 22 patients enrolled at 14 centers, one patient was deemed ineligible prior to start of therapy, since only 13 days had passed since completion of radiation therapy. Characteristics of the remaining 21 subjects are shown in Table 1. Three patients were removed from therapy after cycle 1 and therefore not evaluable for DLT (2 early disease progression; 1 ventriculoperitoneal shunt obstruction requiring surgical revision). Six patients had received prior therapy with at least one other VEGF blocking agent including one or more of bevacizumab, sorafenib, sunitinib or cediranib.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics for Eligible Patients (n=21)

| Characteristics | Number |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Median (Range) | 12.9 (1.9–21.6) |

|

| |

| Sex | |

| Male: Female | 11: 10 |

|

| |

| Prior Chemotherapy Regimens: | |

| Median (Range) | 4 (1–9) |

|

| |

| Patients with Prior Radiation Therapy | 11 |

|

| |

| Patients with Prior VEGF Blocking Therapy | 6 |

|

| |

| Diagnosis | |

| Embryonal (n=9) | |

|

| |

| Hepatoblastoma | 6 |

|

| |

| Neuroblastoma | 2 |

|

| |

| Wilms tumor | 1 |

|

| |

| Sarcoma (n=7) | |

|

| |

| Ewing sarcoma | 1 |

|

| |

| Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma | 1 |

|

| |

| Synovial sarcoma | 1 |

|

| |

| Other soft tissue sarcoma (including clear cell, epithelioid, and leiomyosarcoma) | 4 |

|

| |

| Carcinoma (n=3) | |

|

| |

| Adrenocortical | 1 |

|

| |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 1 |

|

| |

| Small cell-large cell carcinoma | 1 |

|

| |

| Brain tumor (n=2) | |

|

| |

| Ependymoma | 1 |

|

| |

| Pilocytic astrocytoma | 1 |

Dose Escalation and Toxicity

Table 2 summarizes the number of patients experiencing DLT by dose level. One of the first 3 evaluable patients at the 2.0 mg/kg dose level presented with abdominal pain and a decrease in hemoglobin of 1.5 gm/dL, one week following the initial dose. This patient had a large heterogeneous primary adrenocortical carcinoma, and was assessed as having tumor-related grade 3 hemorrhage associated with progression by CT scan. An additional 3 patients were entered at 2.0 mg/kg without incident.

Table 2.

Cycle 1 and 2 Dose-Limiting Toxicities

| Dose | Number of Patients | Description of DLT (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entered | Evaluable | DLT | ||

| 2.0 mg/kg | 7 | 6 | 1 | Hemorrhage, suspected tumor bleed (1) |

| 2.5 mg/kg | 7 | 6 | 0 | |

| 3.0 mg/kg | 7 | 6 | 2 | Tumor/Soft tissue necrosis (1), Tumor pain (1) |

At the 3.0 mg/kg dose level, a patient with synovial sarcoma of the jaw, previously irradiated and with prior sorafenib exposure, experienced dose-limiting grade 3 tumor pain and grade 2 prolonged PTT within 24 hours of the initial dose of aflibercept, requiring intravenous narcotic and hospitalization. CT scan showed tumor necrosis, but no acute hemorrhage. After the pain resolved to baseline, the patient was eligible for retreatment with a dose reduction to 2.0 mg/kg. Imaging after cycle 2 again showed extensive necrosis, enlarging masses and two new nodules, so the patient was removed from protocol for progressive disease. Three additional evaluable patients were entered at 3.0 mg/kg. One patient with epithelioid sarcoma and prior exposure to sorafenib developed grade 3 tumor-related subcutaneous tissue necrosis and abscess formation at a groin site within 14 days of starting therapy and was removed from protocol therapy for delayed wound healing. Since 2 of 6 evaluable patients had DLT, it was determined that the MTD had been exceeded at 3.0 mg/kg.

Interim pharmacokinetic data from patients who received 2.0 mg/kg/day demonstrated the ability to achieve free aflibercept levels in excess of bound aflibercept levels at day 8, but inability to sustain these levels throughout the 14 day dosing interval (Table 4B). The study was, therefore, amended to evaluate an intermediate dose of 2.5 mg/kg. There were no DLTs among the 6 patients entered and an MTD for pediatric patients was established as 2.5 mg/kg.

Table 4B.

Free versus bound aflibercept concentrations

| Dose (mg/kg) | Cycle | Aflibercept concentrations (ng/ml) | Free/Bound | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free | Bound | |||

| 2.0 | Cycle 1, Day 8 (n=3) | 6.86 (6.16–7.56) | 2.50 (1.76–3.96) | 3.87 |

| Cycle 2, Pretreatment (n=4) | 1.50 (0.12–3.43) | 3.61 (2.05–6.22) | 0.52 | |

| Cycle 5, Pretreatmnt (n=3) | 4.20 (1.81–8.01) | 8.16 (4.47–13.20) | 0.43 | |

| 2.5 | Cycle 1, Day 8 (n=5) | 4.96 (3.33–6.02) | 2.39 (2.06–2.69) | 2.10 |

| Cycle 2, Pretreatment (n=5) | 1.45 (0.99–2.01) | 3.35 | 0.44 | |

| Cycle 5, Pretreatment (n=1) | 0.49 | 4.34 | 0.11 | |

| 3.0 | Cycle 1, Day 8 (n=4) | 7.46 (4.59–9.94) | 1.96 (1.78–2.21) | 3.88 |

| Cycle 2, Pretreatment (n=6) | 2.20 (0.81–4.15) | 3.27 (2.79–3.84) | 0.71 | |

| Cycle 5, Pretreatment (n=0) | ||||

Values represent mean concentrations with range in parentheses.

NOTE: Cycle 1, Day 8- N=3, Cycle 2 Pretreatment- N=5 One patient had bound measurements at each time point, but free measurements only for the Cycle 5, pretreatment timepoint.

Non DLTs at least possibly attributable to aflibercept and present in at least 10% of patients over 37 courses are summarized in Table 3. The most frequent were hypertension, mild myelosuppression, fatigue, proteinuria and dysphonia. Of the 9 patients who developed hypertension (43%), 6 patients (29%) required medication to control blood pressure. The median time to onset of first blood pressure elevation was 14 (range 3–247) days, and to initiation of single agent antihypertensive therapy 18.5 (range 3–32) days. No bony abnormalities were reported in 2 patients with open epiphyses who underwent serial plain radiographs.

Table 3.

Non-dose limiting toxicities with possible, probable or definite relationship to protocol therapy

| Toxicity Type | Maximum grade of toxicity observed in a pt | Maximum grade of toxicity observed in a pt across all courses | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Course 1 (18 pt-courses) | Courses 2–8 (19 pt-courses) | |||||

| Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | |

| Hematologic Toxicities | ||||||

| Hemoglobin | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Leukopenia (WBC) | 5 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Lymphopenia | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Neutropenia | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Platelets | 1 | |||||

| Non-hematologic Toxicities* | ||||||

| Hypertension | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Fatigue | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Proteinuria | 3 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Voice changes | 3 | |||||

| ALT | 2 | 2 | ||||

| AST | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Hypoalbuminemia | 2 | 1 | ||||

| PTT | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

Non-hematologic toxicities that were observed in more than 10 % of patients.

Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics and Immunogenicity

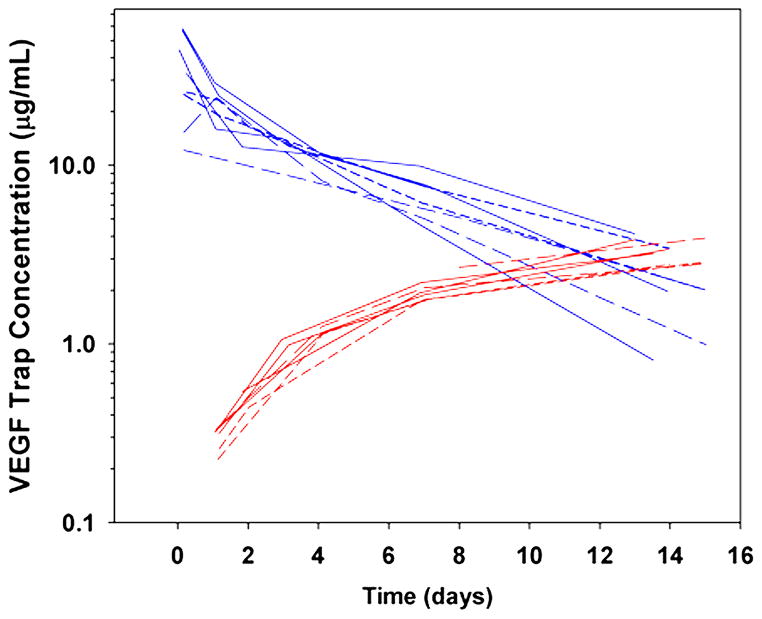

Complete pharmacokinetic profiles for free aflibercept are available for 8 subjects. (Figure 1, upper blue curves). No meaningful difference in Cmax and AUC could be detected between doses of 2 and 2.5 mg/kg in this limited sample, however at 3mg/kg, the mean (range) Cmax of 48.2 (32.9–58.7) μg/ml was approximately double that observed at the lower two doses, and exposure also appeared to increase. The mean half-life, clearance and volume of distribution at steady state (Vss) values of free aflibercept were 4.5 days, 18.4 mL/kg/day and 101 mL/kg, respectively (Table 4A). Within the narrow dose range studied, clearance did not appear to be affected by dose.

Figure 1.

Post-infusion plasma profiles of free (blue) and bound (red) aflibercept for subjects treated with a 1-hour infusion of 2 (short dashed lines), 2.5 (long-dashed lines) or 3 (solid lines) mg/kg aflibercept.

Table 4A.

Mean pharmacokinetics of free aflibercept

| Subject | Dose (mg/kg) | t1/2 (days) | Cmax (μg/ml) | AUC 0–∞ (μg/ml*day) | Cl (mL/day/kg) | Vz (mL/kg) | Vss (mL/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| 1 | 2.0 | 4.97 | 25.8 | 145 | 13.8 | 98.6 | 79.3 |

| 7 | 2.0 | 5.67 | 25.0 | 164 | 12.2 | 99.9 | 92.1 |

| 18 | 2.5 | 5.20 | 12.2 | 109 | 23.0 | 172.4 | 159.2 |

| 20 | 2.5 | 3.55 | 24.1 | 116 | 21.5 | 109.8 | 93.0 |

| 9 | 3.0 | 3.93 | 56.9 | 168 | 17.9 | 101.2 | 82.2 |

| 10 | 3.0 | 4.89 | 58.7 | 187 | 16.0 | 112.9 | 88.2 |

| 12 | 3.0 | 2.64 | 44.5 | 119 | 25.2 | 95.9 | 85.7 |

| 14 | 3.0 | 4.84 | 32.9 | 169 | 17.7 | 123.6 | 126.1 |

|

| |||||||

| Mean | 4.46 | 18.4 | 114 | 101 | |||

| SD | 1.00 | 4.5 | 25 | 28 | |||

| % CV | 23 | 25 | 22 | 28 | |||

Mid cycle (day 8) and trough (pre cycles 2 and 5) free and bound aflibercept concentrations were available for the majority of participants (Table 4B). Bound VEGF:aflibercept complex concentrations were similar across dose levels at day 8 (2.3 ± 0.6 μg/ml) and the end of cycle 1 (3.4 ± 1.0 μg/ml), but the higher value at the end of cycle 1 indicated that a steady-state level of bound aflibercept was not reached before the end of cycle 1 (Figure 1, lower red curves). Bound VEGF:aflibercept complex concentration continued to increase in the few patients sampled before cycle 5, suggesting that steady-state levels of bound aflibercept were not achieved due to a compensatory increase in ligand production. While free aflibercept exceeded bound aflibercept on day 8 for all dose levels studied, this was not sustained across the entire dosing interval (Figure 1). For example, at the MTD, the median (range) free and bound aflibercept serum concentrations on day 8 were 4.96 (3.33–6.02) and 2.39 (2.06–2.69) μg/ml, respectively (ratio free/bound: 2.10), while on day 15 they were 1.45 (0.99–2.01) and 3.35 (2.10–3.97) μg/ml (ratio: 0.44). Nonetheless, detectable free aflibercept at the end of the dosing cycle suggests all available VEGF was bound and neutralized. Sixteen subjects had samples submitted for measurement of anti-aflibercept antibody. The subject who received 16 doses of aflibercept was the only one to develop detectable drug-specific antibody, but without clinical signs of hypersensitivity. In the adult phase I study, no anti-aflibercept antibody was detected. 7 The incidence of antibody development for patients on longer term therapy is currently unknown.

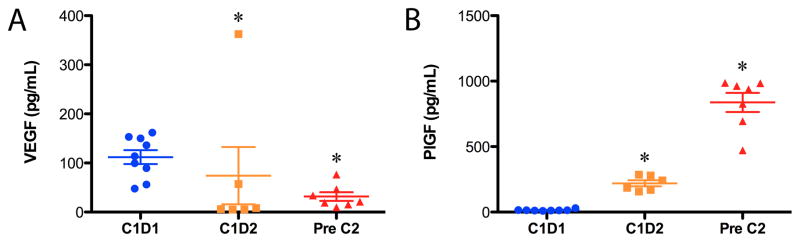

Samples for blood biomarker (VEGF, sVEGFR-2, sVEGFR-1 and PlGF) analysis were available for a minority of patients (n=9; paired n=6). Mean baseline VEGF level was 112 pg/ml [median (range),114 pg/ml (48–153)] and mean baseline PlGF level was 14.9 pg/ml [median (range),13.9 pg/ml (9.4–30.3)]. In aggregate, a rapid and significant decrease in VEGF (p<0.05) and increase in PlGF (p<0.05) from baseline was observed in response aflibercept by day 2, which was maintained through day 15 (Figure 2). The more than ten-fold increase in PlGF levels to 837 pg/ml [median (range): 938 pg/ml (472–987)] by day 15 suggests that aflibercept treatment induced the expression of PlGF, as described in previous reports for aflibercept and other anti-VEGF agents.15–16 Due to small numbers, these pharmacodynamic parameters could not be correlated with dose level or response. In contrast to recent studies of the antiangiogenic multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitors, no modulation of sVEGFR-2 was noted, nor was there a change in sVEGFR-1. Samples for total and subsets of circulating endothelial cells were submitted for 10 patients, but only 4 subjects had three serial time points for analysis. In this small data set no reliable changes could be observed with therapy (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Aflibercept causes a decrease in serum VEGF and increase in PlGF at day 2 (C1D2) and day 15 (just prior to Cycle 2, C2D1) as measured by ELISA. *P<0.05

Response evaluation

The median number of aflibercept 4-week courses was 1 (range, 1–8). There were no objective responses. Three patients had a best response of stable disease with diagnoses of hepatocellular carcinoma (13.4 weeks), clear cell sarcoma (23.6 weeks) and hepatoblastoma (30.8 weeks). None of these three had received prior anti-VEGF therapy.

DISCUSSION

Twenty-one children were treated at aflibercept doses of 2.0, 2.5, and 3.0 mg/kg, with an MTD of 2.5 mg/kg. This pediatric MTD is lower than the adult recommended dose of 4.0 mg/kg, and is in contrast to adult phase I studies, wherein no DLTs were found up to 6 mg/kg.7,9 In the 3 patients who experienced a DLT, the toxicities observed may well be from the effects of VEGF blockade on tumor vasculature, with suspected tumor hemorrhage, tumor pain, and tumor necrosis (rupture). Increased risk of bleeding, including serious intratumoral hemorrhage, was appreciated early on in the development of VEGF targeted therapy including the neutralizing antibody bevacizumab,17 and while infrequent, the association of this toxicity with VEGF inhibitors is supported by a recent meta-analysis.18 While the precise mechanism remains unknown, it is understood that the VEGF pathway plays an important role in maintaining endothelial – vascular mural cell homeostasis, both under normal physiologic and pathologic conditions. Potent VEGF blockade with aflibercept was demonstrated to induce concurrent tumor endothelial and perivascular cell apoptosis, associated with rapid and dramatic reductions in vessel number, branching and perfusion in an orthotopic model of established tumors from the Ewing sarcoma family.4 Such changes may lead to endothelial dysfunction, a loss of vascular integrity and subsequent vascular collapse or bleeding.19 In the setting of progressive disease, it would be difficult to definitively conclude these toxicities were due to these “on target” effects of aflibercept, but the hypothesis is intriguing.

Although the tumor types were various (adrenal cortical carcinoma, epithelioid sarcoma, synovial sarcoma), it has also been found that certain tumors histologies have increased propensity for necrosis and associated hemorrhage after treatment with VEGF blockade (e.g. non-small cell lung cancer of squamous cell histology with bevacizumab).20 Notably, the index case of subcutaneous tumor necrosis, hemorrhage and rupture during adult phase I testing of bevacizumab also occurred in a patient with epithelioid sarcoma, similar to the patient in our trial.17 Whether pediatric tumors in general, or even limited histologies have an increased susceptibility to VEGF inhibition remains to be determined. Asymptomatic pneumothorax was previously seen in pediatric sarcoma patients with pulmonary metastases receiving cediranib, a potent VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, but these were manageable and were not considered dose-limiting. The pneumothoraces in this setting were appreciated only in the presence of tumor response, and were postulated to be due to either necrosis of a pleural based or peripherally located nodule, bronchopleural fistula, or alveolar rupture.12 In the cediranib pediatric phase I trial, and that of bevacizumab13, the maximum tolerated dose for children was approximately equivalent to the adult recommended dosing.

Another potential contributing factor to the tumor associated DLT seen in this study may relate to tumor size: 2 tumors were >10 cm in diameter, and the 3rd >6 cm in diameter. Prior exposure to a VEGF inhibitor and/or radiation to the area of tumor recurrence may have also been predisposing factors. Bulky disease, previous anti-VEGF therapy and prior tumor radiation were not exclusionary and may have compromised our ability to escalate to higher doses.

The presence of DLTs at lower doses of aflibercept than those given in adult clinical trials does not appear to be due to differences in pharmacokinetics. In our pediatric study, we found mean half-life, clearance and volume of distribution at steady state (Vss) values of free aflibercept of 4.5 days, 18.4 mL/kg/day and 101 mL/kg, respectively, which are similar to values reported in adults.7,9 Due to the limited dose range no meaningful difference in Cmax and AUC could be detected between doses of 2.0 and the MTD of 2.5 mg/kg, which was comparable to the adult experience at 2.0 mg/kg, but only a third of the exposure seen at the recommended adult dose of 4.0mg/kg. It is therefore possible, that our MTD is too low to achieve effective concentrations of aflibercept, however, in the presence of severe dose-limiting side effects that might be related to the mechanism of the agent, and may actually be an indication of drug activity, further dose escalation was not felt to be justified.

Preclinical studies have demonstrated that the biologic effects of aflibercept correlate with free aflibercept levels in excess of bound and that the level of bound aflibercept is associated with VEGF production due to the stability of VEGF:aflibercept complex.21 At the MTD of 2.5 mg/kg, free in excess of complexed aflibercept was sustained for 8 days (ratio 2.10), but free aflibercept fell below bound aflibercept by day 15 (ratio 0.44). Free in excess of bound aflibercept was also not sustainable at 3 mg/kg. By contrast, in adults doses of 2 mg/kg and greater were adequate to maintain free in excess of complexed aflibercept.7 However, levels of bound aflibercept in children (3.4 μg/ml) were overall higher than levels observed in adults (1.6 μg/ml, see reference (7)). While it is understood that children with cancer have higher VEGF levels than normal age matched controls, and that circulating VEGF levels decline with tumor remission22–23, it is unknown whether children without cancer have higher circulating endogenous VEGF when compared to healthy adults, or whether pediatric tumor VEGF production, or simply bulk disease, make a greater contribution to systemic levels in patients with cancer. Nonetheless, in our study, the mean baseline plasma VEGF level was 112 pg/ml [n=9; median (range): 114 pg/ml (48–153)] which is more than twice that noted in a cohort of adults with metastatic renal carcinoma of 45.8 [n=69; median (range): 18.6 pg/ml (0.3–855)].24 Bound VEGF concentrations continued to increase in the few children who remained on study for up to 5 courses, suggesting an ongoing compensatory rise in VEGF production. Whether sustained aflibercept excess throughout treatment is required for optimal, durable biological effect in human cancer therapy, or whether short-term excess, but persistent measurable levels of free aflibercept will be sufficient, remains to be determined in adult clinical trials.

As yet there are no accepted or proven biomarkers of angiogenic inhibition. However, rapid changes in the exploratory markers of activity described here are similar to findings in adults, where changes in VEGF and PlGF concentrations have been correlated with decreased vascular permeability on dynamic imaging.25 The incidence of hypertension in children in this trial also appears to be similar to that at the adult recommended phase 2 dose, supporting the biologic activity of aflibercept over the dose range (2.0–3.0 mg/kg) studied. Identifying biomarkers which can indicate adequate exposure and predict which patients might benefit from anti-VEGF therapy, especially given their potential for rare but serious side effects, remains crucial. Measurement of circulating endothelial and progenitor cells is complicated, costly and has not yielded consistent results. Future considerations for trials of antiangiogenic agents in pediatrics should consider incorporating studies of VEGF single nucleotide polymorphisms, dynamic imaging endpoints and an assessment of a broader base of serum markers including the CXCL12 (SDF-1)/CXCR4 axis.26

In summary, the recommended pediatric MTD for aflibercept is 2.5 mg/kg/dose every 14 days, which is lower that the adult recommended dose of 4.0 mg/kg. The occurrence of tumor associated toxicity in the setting of massive disease burden is a strong argument in favor of biologic activity at the dose range tested. While, there were no objective responses to aflibercept, 3 patients did have stable disease, for >12 weeks, suggesting that some pediatric non-bulky tumors may benefit from potent VEGF inhibition therapy.

STATEMENT OF TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

Aflibercept is novel decoy receptor which potently binds VEGF, causing striking inhibition of angiogenesis and tumor regression in pediatric preclinical models. We conducted a phase I and pharmacokinetic study of aflibercept in children with refractory cancer to determine the maximum tolerated dose (MTD). Despite similar pharmacokinetic parameters, children tolerated lower doses of aflibercept than adults, due to dose-limiting tumor pain, necrosis and hemorrhage. Possible explanations for increased tumor-related toxicity include tumor bulk, tumor histology and the relative contribution of VEGF to pediatric tumor growth. At the MTD, children achieved, but did not sustain, free in excess of bound aflibercept. Nonetheless, presumed effects on tumor vasculature and modulation of plasma biomarkers imply biologic activity. The results of this trial suggest that both tumor and host factors may determine susceptibility to aflibercept and highlight the need to identify biomarkers able to predict which patients will benefit from anti-VEGF therapy.

Acknowledgments

Support: Supported by Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation, tay-bandz, Sanofi-Aventis and the Phase I/Pilot Consortium Grant U01 CA97452 of the Children’s Oncology Group from the NCI, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA.

We thank Elizabeth O’Connor, Biljana Georgievska, and Nicole Stewart from the COG Phase1/Pilot Consortium Operations Center for outstanding data management and administrative support throughout the development and conduct of this trial, and Bing Wu for her diligence in carrying out the biomarker analysis.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Prior Presentations: Presented in part at the 2010 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting (Chicago, IL).

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00622414

References

- 1.Ferrara N, Kerbel RS. Angiogenesis as a therapeutic target. Nature. 2005;438:967–74. doi: 10.1038/nature04483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature. 2011;473:298–307. doi: 10.1038/nature10144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holash J, Davis S, Papadopoulos N, et al. VEGF-Trap: a VEGF blocker with potent antitumor effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11393–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172398299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang J, Frischer JS, Serur A, et al. Regression of established tumors and metastases by potent vascular endothelial growth factor blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7785–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432908100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kadenhe-Chiweshe A, Papa J, McCrudden KW, et al. Sustained VEGF blockade results in microenvironmental sequestration of VEGF by tumors and persistent VEGF receptor-2 activation. Molecular cancer research : MCR. 2008;6:1–9. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim ES, Serur A, Huang J, et al. Potent VEGF blockade causes regression of coopted vessels in a model of neuroblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11399–404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172398399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lockhart AC, Rothenberg ML, Dupont J, et al. Phase I study of intravenous vascular endothelial growth factor trap, aflibercept, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:207–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.9237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cutsem E, Tabernero J, Lakomy R, et al. Intravenous (iv) aflibercept versus placebo in combination with irinotecan/5-FU (FOLFIRI) for secondline treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (mcrc):results of a multinational phase III trial (efc10262-VELOUR) Annals of Oncology. 2011;22 (suppl 5):v18. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coleman RL, Duska LR, Ramirez PT, et al. Phase 1–2 study of docetaxel plus aflibercept in patients with recurrent ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:1109–17. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70244-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:555–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0 (CTCAE) 2006 http://ctep.info.nih.gov.

- 12.Fox E, Aplenc R, Bagatell R, et al. A phase 1 trial and pharmacokinetic study of cediranib, an orally bioavailable pan-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor, in children and adolescents with refractory solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:5174–81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.9674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glade Bender JL, Adamson PC, Reid JM, et al. Phase I trial and pharmacokinetic study of bevacizumab in pediatric patients with refractory solid tumors. a Children’s Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:399–405. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.9230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mancuso P, Burlini A, Pruneri G, et al. Resting and activated endothelial cells are increased in the peripheral blood of cancer patients. Blood. 2001;97:3658–61. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Groot JF, Piao Y, Tran H, et al. Myeloid biomarkers associated with glioblastoma response to anti-VEGF therapy with aflibercept. Clinical cancer research an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17:4872–81. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Batchelor TT, Sorensen AG, di Tomaso E, et al. AZD2171, a pan-VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, normalizes tumor vasculature and alleviates edema in glioblastoma patients. Cancer cell. 2007;11:83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon MS, Margolin K, Talpaz M, et al. Phase I safety and pharmacokinetic study of recombinant human anti-vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:843–50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sonpavde G, Bellmunt J, Schutz F, et al. The Double Edged Sword of Bleeding and Clotting from VEGF Inhibition in Renal Cancer Patients. Curr Oncol Rep. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11912-012-0237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamba T, McDonald DM. Mechanisms of adverse effects of anti-VEGF therapy for cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:1788–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson DH, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny WF, et al. Randomized phase II trial comparing bevacizumab plus carboplatin and paclitaxel with carboplatin and paclitaxel alone in previously untreated locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22:2184–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rudge JS, Holash J, Hylton D, et al. VEGF Trap complex formation measures production rates of VEGF, providing a biomarker for predicting efficacious angiogenic blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18363–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708865104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okur FV, Karadeniz C, Buyukpamukcu M, et al. Clinical significance of serum vascular endothelial growth factor, endostatin, and leptin levels in children with lymphoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;55:1272–7. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pavlakovic H, Von Schutz V, Rossler J, et al. Quantification of angiogenesis stimulators in children with solid malignancies. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:756–60. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20010601)92:5<756::aid-ijc1253>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zurita AJ, Jonasch E, Wang X, et al. A cytokine and angiogenic factor (CAF) analysis in plasma for selection of sorafenib therapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:46–52. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Groot JF, Piao Y, Tran H, et al. Myeloid Biomarkers Associated with Glioblastoma Response to Anti-VEGF Therapy with Aflibercept. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:4872–4881. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jain RK, Duda DG, Willett CG, et al. Biomarkers of response and resistance to antiangiogenic therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6:327–38. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]