Abstract

Objective: Despite an increasing movement toward shared decision making and the incorporation of patients' preferences into health care decision making, little research has been done on the development and evaluation of support systems that help clinicians elicit and integrate patients' preferences into patient care. This study evaluates nurses' use of choice, a handheld-computer–based support system for preference-based care planning, which assists nurses in eliciting patients' preferences for functional performance at the bedside. Specifically, it evaluates the effects of system use on nurses' care priorities, preference achievement, and patients' satisfaction.

Design: Three-group sequential design with one intervention and two control groups (N=155). In the intervention group, nurses elicited patients' preferences for functional performance with the handheld-computer–based choice application as part of their regular admission interview; preference information was added to patients' charts and used in subsequent care planning.

Results: Nurses' use of choice made nursing care more consistent with patient preferences (F=11.4; P<0.001) and improved patients' preference achievement (F=4.9; P<0.05). Furthermore, higher consistency between patients' preferences and nurses' care priorities was associated with higher preference achievement (r=0.49; P<0.001).

Conclusion: In this study, the use of a handheld-computer–based support system for preference-based care planning improved patient-centered care and patient outcomes. The technique has potential to be included in clinical practice as part of nurses' routine care planning.

With the recent movement toward shared decision making in health care, a number of models, methods, and evaluative strategies to foster shared decision making have been developed. In the clinical, health services, and methodological literature, shared decision making refers to the concept of involving patients and their health care providers in making treatment decisions that are informed by the best available evidence about treatment options and that consider patients' preferences.

Devices to assist patients in shared decision making have been called “decision aids,”1 and cumulative evidence supports their effectiveness. Studies evaluating decision aids for patients have reported higher scores on cognitive functioning and social support,2 more active and satisfying participation in decision making,3 better scores on general health perceptions and physical functioning,4 improved knowledge,5 and reduced decisional conflict.1 However, decision aids have so far been confined to the relatively narrow segment of decisions about single episodes of screening or treatment choices. Little attention has been given to the development of systems that help clinicians elicit and integrate patients' preferences into the ongoing processes of care over time and as part of clinical practice.

Although decision aids have been shown to be helpful to patients, it has been argued that decision support systems for eliciting patients' preferences could also support clinicians in making care decisions consistent with patients' preferences, and that successful efforts in this direction would lead to better patient outcomes.6,7 However, the development of decision support systems designed to support clinicians in eliciting and integrating patients' preferences into their clinical practice has received little attention. Developments of decision support systems for clinicians have mainly been devoted to knowledge-based systems designed to produce patient-specific options and recommendations, such as computer-based clinical guidelines. Other examples of clinical decision support systems include systems that apply rules to detect undesirable trends and events during treatment, offer reminders and messages about diagnostic and therapeutic possibilities, and alert clinicians to potential serious situations.8

Evidence shows that clinical decision support systems can enhance clinicians' compliance with system recommendations and to some degree improve clinical patient outcomes.9,10 Yet such systems rarely offer systematic methods for eliciting patients' preferences or incorporate algorithms for the integration of patients' preferences into care planning. Furthermore, there has been only limited research addressing 1) whether the use of computer-based decision support systems to assist in the elicitation of patients' preferences would in fact prompt clinicians to make care decisions consistent with patients' preferences, and 2) whether decisions based on the use of such tools would improve patient outcomes. Developing and testing the effects of clinical support systems for preference elicitation and care planning on clinical decisions and patient outcomes can, therefore, make an important contribution to research in this area and, ultimately, to patient-centered care.

This paper reports the results of nurses' use of Choice (Creating better Health Outcomes by Improving Communication about Patients' Expectations), a handheld-computer–based support system for preference-based care planning, which helps nurses elicit patients' preferences for functional performance at the bedside—specifically, the effects of its use on nurses' care priorities and patient outcomes of preference achievement and satisfaction.

Choice

Choice was designed to include tailored information about dimensions of functional performance; assist nurses in the clarification of patients' values and the relative importance they place on functional performance dimensions; process and display structured information about patients' preferences in a format that is useful for care planning; provide guidance in setting care priorities that are consistent with patients' preferences; and, finally, provide a benchmark for evaluating the congruence between patients' preferred and achieved functional performance as outcomes of care. Choice was purposely designed in a way that the elicitation of patients' preferences is integrated in the regular care process as part of nurses' routine patient admission interview.

Choice was developed on a PalmPilot handheld computer (Palm, Inc., Santa Clara, California), using a Microsoft Access database and Pendragon developing software. Handheld computer technology was chosen as platform because the device has the advantage of low weight (less than 1 lb), fits in the palm of the hand, and is, therefore, unobtrusive. Handheld computers are small enough to be carried in the pocket of a laboratory coat, and information can be easily exchanged with other clinical applications.

Using the Choice application for preference elicitation, nurses move successively through a series of screens that contain 14 dimensions of functional performance. System use involves selecting pre-defined dimensions and importance-weights on the screen; it requires little additional data entry and only limited computer skills.

Following the elicitation interview procedure in this study, which is described below, nurses ticked with a pen the importance-weights that patients assigned to each dimension, which were displayed on a scale on the screen, and selected the relevant descriptors that further specified each dimension. Choice also allows more detailed individualized descriptions to be added to each dimension as free text. In addition, it contains five free fields so that patients can include other, individually selected dimensions, without being constrained by the pre-defined dimensions of Choice. The PalmPilot also displays a keyboard that nurses can use for additional data entry.

Data on patients' preferences that were entered into the PalmPilot computer during the elicitation interview were transferred to a desktop computer through a cradle, and then were processed and printed. Transferring and printing information about a patient's preferences required the push of a button.

Previous Studies ofC hoice

Choice builds on several previous studies by the author. After the feasibility of the preference elicitation technique and algorithm in Choice was refined and tested,11 the effect of a paper-based version on nursing care and patient outcomes was tested in a sample of 151 elderly patients.12 When nurses in the intervention group were provided with information about patients' preferences, there was a significant increase in congruence between patients' preferences and nursing care priorities, better patient outcomes in improved preference achievement and physical functioning at discharge, and, indirectly, increased patients' satisfaction in comparison with that of control groups.12

After refining the dimensions of functional performance and again using Choice successfully in a new sample of 55 patients,13 it was timely to evaluate Choice with the addition of two new elements—as a computer-based application, and as an integrated part of nurses' clinical practice. In previous studies, Choice had been evaluated in a paper-based and investigator-administered form.

Purpose

The ultimate value of a clinical support system is determined by the degree to which it repeatedly can demonstrate positive results in clinical practice settings. Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to replicate elements of the previous evaluation study to determine whether the same, or similar, results would occur if nurses in clinical practice used the handheld-computer–based Choice application.

This study evaluated the effects of nurses' use of the handheld-computer–based Choice for preference-based care planning—specifically, effects on congruence between patients' preferences and nurses' care priorities as reflected in the nursing documentation, and patients' preference achievement and patients' satisfaction as outcomes of care.

Using a three-group sequential design with one intervention and two control groups, the following three hypotheses were tested:

Nurses' care priorities addressed in the nursing documentation are more congruent with patients' preferences for functional performance.

Patients' preference achievement at discharge is greater.

Patients are more satisfied with their care when nurses use choice for preference elicitation and care planning than when Choice is not used.

Because the health status of patients normally influences the amount and type of nursing care they receive and the outcomes of care, these hypotheses were controlled for patients' physical functioning and signs and symptoms at baseline.

Methods

Design

Patients were enrolled consecutively over a period of 8 months. Consenting patients were interviewed twice at their bedsides, the first time within 24 hours of admission and the second time at discharge or, alternatively, after 12 days if they stayed longer, to avoid large variability in the time period between interviews. To be included, patients had to be 64 years of age or older, alert, and oriented and had to have been admitted for a minimum of 3 days.

To avoid contamination of treatment, patients were enrolled in tandem, whereby data collection for control group C was completed first, followed by data collection for control group B and, finally, intervention group A. Baseline characteristics of patients' physical functioning, signs and symptoms, and demographic variables were collected to control for potentially confounding effects of patients' health status and to ensure equivalence among groups, since randomization was not possible.

Control group C, in which patients received the usual care, was added to this study to control for a possible effect of increased attention from health professionals when patients were asked about their preferences, as in groups A and B. This may have induced expectations in patients that could have influenced results in both groups. Including control group C also ensured that demographic and control variables were stable patient characteristics at the study site over time.

Preference elicitation in groups A and B followed the same procedures, except that the interviews were conducted by the admitting registered nurse for intervention group A but by a research assistant for control group B. Research assistants were also experienced registered nurses, and their training in preference elicitation was identical to that of staff nurses. Thus, the preference elicitation procedures were, from the patients' viewpoints, very similar in both groups. The group differences were in the clinical involvement of nurses in obtaining those preferences, and the addition of preference information to patients' care plans for subsequent care planning, which both occurred only in group A.

Measurement

Preference Elicitation

Choice captures 14 dimensions of functional performance that are necessary for patients to perform physical, psychological, social and occupational activities in the normal course of their lives to meet basic needs, fulfill usual roles, and maintain their health and well-being.14 Examples include mobility, rest and activity, pain management, management of medications and treatments, and adjustments to changes in lifestyle.

Choice uses a non–utility-based psychometric approach to eliciting patients' preferences. At the beginning of the elicitation interview, patients were asked to identify two or three self-selected functional performance dimensions that they particularly wanted to improve, and that they consequently wished to be a focus of care. Next, patients were asked to examine carefully each of the Choice dimensions and select importance weights on five-point rating scales adjacent to each dimension, ranging from "not important" to "very important." Patients were given a paper copy of the Choice preference assessment form, so they could see the same information that the interviewer was seeing on the screen. The interviewer entered patients' responses into the handheld computer simultaneously during the interview.

Preference elicitations in this and previous studies11–13 showed that Choice discriminates between the importance of different dimensions to patients. For data analysis, importance weights for all dimensions were added to a total preference score for each patient, providing interval level data with possible ranges of 0 to 76. These total scores were used in the subsequent analyses of patients' perceived preference achievement at discharge, as discussed later.

Preference Achievement

Patients were asked at discharge to review those dimensions of functional performance that they had identified during the admission interview by assigning them importance-weights greater than 0, and to rate the degree of their perceived achievement in each of these dimensions. Rating scales adjacent to each functional performance dimension ranged from 0 to 10, where 0 indicated no improvement and 10 indicated complete achievement.

For data analysis, two measures of preference achievement were computed. First, the achievement values for each dimension were multiplied by the importance-weights assigned by patients during the admission interview. These products were then added to a total score, providing a measure of preference-weighted achievement for each patient. Second, to estimate preference achievement in another, simpler way, the (unweighted) achievement values for all dimensions were summed and then divided by patients' preference scores. This provided a measure of patients' overall achievement on those functional performance dimensions that they had selected at admission, called “overall achievement” in the Results section, below.

Nurses' Care Priorities

Nurses' care priorities for the patients' first three admission days were abstracted from patients' charts according to a specially developed abstraction scheme described in more detail elsewhere.12,15 The two research assistants were thoroughly trained in abstraction rules. Based on the amount, type, frequency, and location of documentation of nursing care aspects in patients' charts, a priority rating ranging from 1 to 5 (with 1 as the highest priority rating) was assigned to each nursing care aspect using the heuristics and detailed decision rules developed in a separate, previous study.15

To confirm the validity of the rating method of nurses' care priorities from patients' charts in this study, the research staff's priority ratings for a sample of 15 patients were first compared with priority ratings of two or three nurses who had cared for the same patient prior to study enrollment. The same procedure was then repeated regularly throughout the study for 20 percent of the sample. The mean overall consistency score between the research staff's and nurses' care priorities remained between 0.71 and 0.75. This was higher than the mean consistency score of 0.71 for priority ratings among nurses only, which was used as the gold standard for acceptable validity of chart abstractions as measure of nurses' care priorities.

To ensure reliability and to avoid a potential bias from raters' knowledge of patients' group assignments or from slightly altered abstractions with increasing experience, all patient charts were again rated after completion of the study. The copies of charts that were used were stripped of all information from which raters could have inferred patients' identities or group assignments. The numbers and types of functional performance dimensions and priority ratings abstracted by the two raters were compared. The few discrepancies that were found were resolved through discussion. Data analysis of nursing care priorities was based on these final chart abstractions.

Patient Satisfaction

Patient satisfaction with nursing care was measured with the LaMonica-Oberst Patient Satisfaction Scale (LOPSS).16 This 41-item instrument is an indirect measure of patients' satisfaction, in which the level of satisfaction is inferred from respondents' judgments about the extent to which specific nurse behaviors did or did not occur. Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Patient satisfaction is conceptualized as the degree of congruence between patients' expectations of nursing care and their perceptions of the care actually received.16

Control Variables

Physical functioning and signs and symptoms were measured with five subscales of the Sickness Impact Profile (SIP)17 and the Signs and Symptoms Checklist (SSC),18 which were used as covariates to control for potential effects of patients' baseline functional status and symptoms on nurses' care priorities and patient outcomes. Descriptive statistics and reliability coefficients are displayed in Table 1▶. There were no significant differences in these variables between groups, ensuring group equivalence at baseline.

Table 1 .

Descriptive Statistics, Group Differences, and Reliability Coefficients for Control Variables at Baseline: Signs and Symptoms Checklist (SSC) and Sickness Impact Profile (SIP)

| Control Variable | Experimental Group A (n=52) |

Control Group B (n=52) |

Control Group C (n=51) |

F | df | Cronbach Alpha | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Signs and Symptoms Checklist | 10.14 | 5.68 | 10.43 | 6.77 | 9.07 | 5.63 | 0.70 | 152 (2) | 0.72 |

| Sickness Impact Profile | 38.49 | 9.32 | 38.13 | 9.91 | 35.34 | 9.83 | 1.63 | 152 (2) | 0.78 |

Procedures

At admission, consenting patients in all three groups were asked demographic questions, and the SIP and the SSC, administered by the research staff, were completed both at admission and at discharge. At discharge, all patients also completed the patients' satisfaction questionnaire (LOPSS). Prior to data collection in intervention group A, all 34 registered nurses who were employed at that time in the study units completed a 1.5- to 2-hour-long session (with two or three registered nurses per session) in which they were instructed in the use of Choice.

In intervention group A, nurses used Choice to elicit patients' preferences for functional performance as part of their admission interview, as described above; afterward, they transferred the information collected on the PalmPilot to the desktop computer, and the patients' preference form was processed and printed in the order of the importance patients had assigned to functional performance dimensions. The nurse then placed the preference form in the patient's care plan.

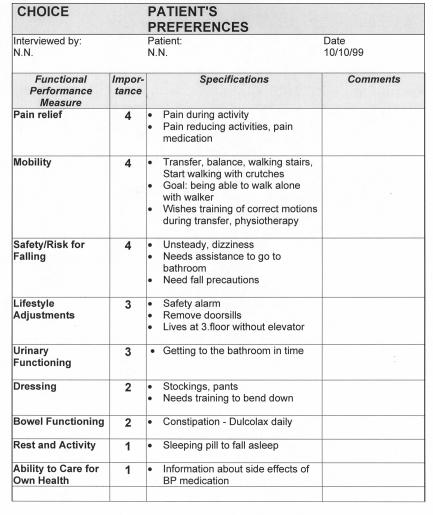

Each preference form reflected the patient's individually selected dimensions of functional performance with their specifications and priority. With a glance at this form, nurses could find concise information about dimensions of functional performance that it was more or less important to the patient to improve, denoting priorities for care. Figure 1▶ shows a sample preference form.

Figure 1 .

Sample of patient preference form

In control group B, patients' preferences were elicited similarly by the research staff, but this information was not provided to nurses at the unit. In control group C, patients received the usual care. The evaluation of patients' preference achievement was completed by the research staff in intervention group A and control group B at discharge. Preference elicitations at admission lasted 10 to 25 minutes. The evaluation of patients' perceived preference achievement at discharge took about 10 to 15 minutes.

Results

Sample

The patient sample in this study consisted of 155 patients (51 or 52 per group) admitted to a medical care unit for the elderly and a rehabilitation unit at a university hospital in Oslo, Norway. Of these, 78.7 percent were women and 21.3 percent were men. The mean age was 80.8 years (SD 5.9 years; range, 64 to 94 years); the mean years of formal education was 8.8 (SD 2.7 years; range, 5 to 18 years). Fifty percent were admitted for medical reasons, and 50 percent were admitted for surgical rehabilitation. The mean length of stay was 16 days (SD 13.5 days; range, 4 to 85 days).

A total of 28 nurses (mean age, 35 years; range, 23 to 63 years), or 82 percent of those who were trained in the use of Choice, admitted patients on their shifts during the data collection period for group A and thus had the opportunity to use Choice between one and seven times (mean number of uses, 2.96).

Group Differences in Nurses' Care Priorities

The first hypothesis tested was that nurses' care priorities addressed in the nursing documentation were more congruent with patients' preferences for functional performance when nurses used Choice for preference elicitation and care planning than when they did not use Choice. Intervention group A and control group B and two variables were used for testing this hypothesis, controlling for physical functioning (SIP) and signs and symptoms (SSC).

In the first ANCOVA model, the “match” variable was computed as dependent variable, reflecting the proportion of care priorities in the nursing documentation that addressed at least once functional performance dimensions selected by patients at admission. In other words, the greater the proportion, or “match,” between documented nursing care and patients' preferences, the higher the degree of congruence between patients' preferences for functional performance and nurses' care priorities.

In the second ANCOVA model, summed discrepancy scores were used as the dependent variable, measuring discrepancies between the importance-weights patients had assigned to functional performance dimensions and ratings of nurses' care priorities. For example, if a patient had indicated that a particular functional performance dimension was very important and this dimension was also a high priority for nurses, then discrepancy on this dimension was low. The lower the total discrepancy scores for all dimensions, the higher the congruence between patients' preferences and nurses care priorities.

Physical functioning had a significant correlation with the match variable (r=0.40, P<0.001), whereas the summed discrepancy scores were significantly associated with signs and symptoms (r=0.22, P<0.05). Therefore, SIP scores and SSC scores were kept as covariates in the ANCOVA models that were used for hypothesis testing.

The means and standard deviations (Table 2▶) show that mean matches were significantly higher in the intervention group than in the control group. This supported the first hypothesis, that nurses' care priorities were more congruent with patients' preferences when nurses used Choice than when they did not. However, there were no significant group differences in the discrepancy variable. This suggests that when nurses used Choice, they more often included those dimensions of functional performance that patients had selected in their care planning, but the nursing documentation did not reflect that they also took into account the relative importance patients had placed on these dimensions.

Table 2 .

Group Differences in Congruence Between Patient Preferences and Nurses' Care Priorities

| Dependent Variable | Control Group B (n=52) |

Experimental Group A (n=52) |

F | df | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Match | 0.32 | 0.17 | 0.44 | 0.19 | 11.4* | 103 (1) |

| Discrepancy | 4.7 | 1.3 | 4.7 | 0.11 | 0.89 | 103 (1) |

*p=0.001

Group Differences in Preference Achievement

The second hypothesis was that patients' preference achievement was greater when nurses used Choice for preference elicitation and care planning than when nurses did not use Choice. The preference-weighted and overall achievement scores were used in these analyses, as described above. Only physical functioning had a significant correlation with the dependent variable of preference achievement (r=0.27, P<0.05) but not signs and symptoms (SSC). Therefore, only SIP scores were kept as covariate in the ANCOVA models.

Table 3 ▶shows that adjusted group means for preference-weighted and overall achievement scores were significantly higher for patients in the intervention group, thus supporting the second hypothesis. Using Choice resulted in greater preference achievement.

Table 3 .

Group Differences in Preference Achievement

| Dependent Variable | Control Group B (n=52) |

Experimental Group A (n=52) |

F | df | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Preference-weighted achievement | 22.2 | 14.7 | 28.9 | 16.4 | 4.87* | 103 (1) |

| Overall achievement | 5.8 | 3.2 | 7.9 | 4.9 | 6.87* | 103 (1) |

*p<0.05

Patient Satisfaction

The third hypothesis was that patients' satisfaction was greater when nurses were provided with information about patients' preferences than when nurses were not provided with this information. All three groups were used for this analysis. Cronbach's alpha as a measure of reliability of the LOPSS in this study was 0.89. Table 4▶ shows that adjusted group means for patients' satisfaction were not significantly different across groups, and the third hypothesis was not supported. Nurses' use of Choice did not result in greater patients' satisfaction.

Table 4 .

Group Differences in Patient Satisfaction

| Control Variable | Control Group C (n=50) |

Control Group B (n=46) |

Experimental Group A (n=49) |

F | df | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Patient satisfaction | 238.6 | 30.9 | 239.7 | 26.3 | 232.4 | 27.9 | 0.92 | 103 (2) |

Additional Results

Relationship Between Nurses' Care Priorities and Preference Achievement

This study investigated not only the effects of the intervention on nurses' care priorities and patient outcomes of preference achievement and patients' satisfaction, but also how they occurred. Therefore, the relationship between patients' preference achievement and congruence between patients' preferences and nurses' care priorities was also investigated.

Zero-order correlations showed a significant relationship between preference achievement and the match variable (r=0.49, P<0.001), the variable that indicated whether functional performance dimensions selected by patients where addressed in the nursing documentation at least once. This finding supports the possibility that better preference achievement in the intervention group could indeed be attributed to nursing care that was more consistent with patients' preferences. This relationship was evident only in the match variable; there was no significant correlation between preference achievement and discrepancy scores.

Group Differences in Number of Documented Nursing Interventions

Another finding was not hypothesized but supported the positive relationship between nursing care priorities and preference achievement—namely, that significantly more nursing interventions per patient in relation to their selected functional performance dimensions were documented in the nursing documentation in intervention group A, as shown in Table 5▶. This suggests that nurses indeed used the information about patients' preferences actively in their care planning.

Table 5 .

Group Differences in Number of Documented Nursing Interventions

| Dependent Variable | Control Group B (n=52) |

Experimental Group A (n=52) |

F | df | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Number of interventions | 9.5 | 6.5 | 12.1 | 6.7 | 4.6* | 103 |

*p<0.05

Discussion and Conclusion

This study showed that using handheld-computer support for preference-based care planning can be a feasible strategy to influence nursing care to be more consistent with patients' preferences and to improve patients' preference achievement. The evaluation of patients' perceived preference achievement facilitated immediate feedback about the effect of nursing care on patient outcomes from the perspective of the patient. The validity of these findings is supported by the fact that this study replicated results from a previous study in which the preference elicitation technique of Choice was tested in a paper-based and investigator-administered form.12 That similar results also appeared when Choice was used by nurses as part of their clinical practice is encouraging. It suggests that the elicitation and care-planning methods of Choice have the potential to be included in clinical practice as a part of nurses' routine admission assessment.

A limitation of this study, compared with the previous study, was that complete data sets on physical functioning (SIP) at discharge were difficult to obtain. Although physical functioning at baseline was conceptualized as a control variable in both studies, additional data were collected at discharge in the first study, in which a significant positive effect of the intervention on physical functioning was found. Therefore, the SIP was also part of the discharge data collection protocol in this study.

Unfortunately, and for reasons that are not quite clear, a number of patients had incomplete sets of SIP discharge data, leaving us with insufficient data for an adequate analysis. Since it was most important to obtain discharge data from patients on the study's main outcome measures (preference achievement and patients' satisfaction), the SIP questionnaire was administered as the last of three questionnaires. Obtaining complete data sets had not been a notable problem in the first study, and this difficulty had not been detected during pilot testing.

Although this study repeated the positive effects of Choice on nursing care priorities and preference achievement, a demonstration of similar effects on physical functioning, as in the previous study, would have strengthened its results. Conclusions should, therefore, be made with caution.

A deviation from results in the previous study12 was found in the relationship between patients' preferences and nursing care priorities as reflected in the nursing documentation. In this study, there were significant group differences only in the proportion of patient-selected functional performance dimensions that were addressed in the nursing documentation at least once (the match variable). There were no significant group differences, as in the previous study, in the relationship between the strength of importance patients had placed on functional performance dimensions and the degree of priority with which these dimensions were addressed in the nursing documentation (the discrepancy variable). However, this finding may be attributed to differences in nursing documentation practices rather than to a true inattentiveness, among nurses in this study, to the importance patients place on functional performance dimensions.

While the first study was conducted in a special care unit for the elderly at University Hospitals in Cleveland, an American hospital in which structured and comprehensive documentation routines were well established, this study was conducted in a Norwegian university hospital, where the requirements for nursing documentation are different and where a larger part of nursing care is probably taking place without ever being documented. Therefore, it may have been more difficult in this study to detect differences in the strength of nurses' care priorities from the nursing documentation.

At first glance, it may seem somewhat surprising that there was no direct effect of the intervention on patients' satisfaction in this study or the initial one. Several reasons are possible. One might be that the LOPSS lacked the sensitivity to measure the effect of the intervention on patients' satisfaction. LOPSS includes only a few items that are related to patients' preferences or aspects of individualized care. Another possible reason may be the influence of other factors unrelated to the effect of the intervention on patients' satisfaction. Variables found in the literature to be associated with patients' satisfaction are continuity of care, age, education, patients' expectations, illness status, treatment outcome, health providers' behaviors, their interpersonal relationships with patients,19,20 and the acquisition of knowledge and experience by a patient over repeated visits. These possible sources of variation in patients' satisfaction in combination with the use of an instrument that may not have been particularly sensitive to the intervention may explain why there were no significant differences among the study groups on total patients' satisfaction scores.

Choice is the first computer-based support system for preference-based care planning used by nurses in clinical practice that has shown applicability and indications of effectiveness for improving nursing care and patient outcomes consistent with patients' preferences. Because of the novelty of these types of systems, however, the field requires considerably more research. A worthwhile route for further inquiry would be to explore the mechanisms by which these effects occurred.

Possible explanations of the effects of Choice may be an increased awareness by nurses of patients' preferences and thus a shift in the focus of care planning; the interaction that takes place when Choice is used during the patient assessment interview, which fosters shared decision making; the way information about patients' preferences is conveyed and integrated into care planning; and other changes in nursing practice initiated by Choice. A more in-depth exploration of these aspects would make an important contribution to the further development of Choice and other similar support systems.

Future evaluation studies should also add outcome measures other than nurses' care priorities and preference achievement. Patients' personal values and experiences are at the heart of research on patients' preferences, and variables that tap these personal, subjective experiences are, therefore, important. However, the clinical value of support systems for preference-based patient care would be considerably greater if the systems could be shown to improve a wider range of patient and provider outcomes, such as functional status, symptom relief, health-related quality of life, and provider satisfaction.

Furthermore, studies are needed that begin to test support systems for preference-based care planning for patient populations other than elderly patients with impaired functional performance, which so far have been the target group for Choice. Also, little is known about the range of clinical decision situations and settings in which these systems may be applicable, e.g., whether they are suited only to planning care for patients with chronic, but not acute, conditions.

While the Choice approach to preference elicitation is meant to be generic for decision problems with certain characteristics, there may be alternative approaches to preference-based care planning; and different techniques may need to be tailored to different health problems and populations. Furthermore, studies that systematically collect data about patients' preferences for different patient populations, settings, and health states would help researchers gain a better understanding of the patients' perspectives, and thus support the clarification of variables and knowledge necessary for developing support systems for preference-based care. Long-term development should also aim to integrate information about patients' preferences directly into the computer-based patient record, and provide mechanisms by which information about patients' preferences is automatically shared with the interdisciplinary care team.

This study was supported by grant 130007/320 from the Norwegian Research Council.

References

- 1.O'Connor AM, Rostrom A, Fiset V, et al. Decision aids for patients facing health treatment or screening decisions: systematic review. BMJ. 1999;319:731–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boberg EW, Gustafson DH, Hawkins RP, et al. CHESS: the comprehensive health enhancement support system. In: Brennan PF, Schneider SJ, Tornquist E (eds). Information Networks for Community Health. New York: Springer; 1997:171–88.

- 3.Molenaar S, Sprangers MA, Postma-Schuit FC, et al. Feasibility and effects of decision aids. Med Decis Making. 2000;20: 112–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldstein MK, Clarke AE, Michelson D, Garber AM, Bergen MR, Lenert LA. Developing and testing a multimedia presentation of a health-state description. Med Decis Making. 1994; 14:336–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Connor AM, Tugwell P, Wells GA, et al. Randomized trial of a portable, self-administered decision aid for postmenopausal women considering long-term preventive hormone therapy. Med Decis Making. 1998;18:295303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fowler FJ, Cleary PD, Magaziner J, Patrick DL, Benjamin K. Methodological issues in measuring patient reported outcomes: the agenda of the work group on outcome assessment. Med Care. 1994;32(suppl):JS65–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasper JF, Mulley AG, Wennberg JE. Developing shared decision making programs to improve the quality of health care. Qual Rev Bull. 1992;18:183–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Metzger JB. The potential contributions of patient care information systems. In: Drazen EL, Metzger JB, Ritter JL, Schneider MK (ed). Patient Care Information Systems: Successful Design and Implementation. New York: Springer, 1995:1–30.

- 9.Hunt DL, Haynes RB, Hanna SE, Smith K. Effects of computer-based clinical decision support systems on physician performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA. 1998; 280:1339–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shiffman RN, Liaw Y, Brandt CA, Corb GJ. Computer-based guideline implementation systems: a systematic review of functionality and effectiveness. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1999; 6:104–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruland CM, Kresevic D, Lorensen M. Including patients' preferences in nurses' assessment of older patients. J Clin Nurs. 1997;6:495–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruland CM. Decision support for patient preference-based care planning: effects on nursing care and patient outcomes. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1999;6:304–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruland CM. Do patient preferences change during the course of their hospitalization and recovery? Med Decis Making. 2000;20:482. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leidy NK. Functional status and the forward progress of merry-go-rounds: towards a coherent analytical framework. Nurs Res. 1994;43:196–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruland CM. Integrating patient preferences for self-care capability in nursing care: effects on nurses' care priorities and patient outcomes [doctoral dissertation]. Cleveland, Ohio: Case Western Reserve University; 1998:198.

- 16.La Monica EL, Oberst MT, Madea AR, Wolf R. Development of a patient satisfaction scale. Res Nurs Health. 1986;9:43–50 (used with permission). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergner M, Bobbitt R, Carter W, Gilson B. The Sickness Impact Profile: development and final revision of a health status measure. Med Care. 1981;19:787–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holzemer WL, Henry SB, Nokes KM, et al. Validation of the Sign and Symptom Checklist for Persons with HIV Disease (SSC-HIV). J Adv Nurs. 1999;30:1041–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis JR. Patient views on quality care in general practice: literature review. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:655–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall JA, Dorman MC. Meta-analysis of satisfaction with medical care: description of research domain and analysis of overall satisfaction levels. Soc Sci Med. 1988;27:637–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]