Abstract

Addiction is a disease that is characterized by compulsive drug-seeking and use despite negative health and social consequences. One obstacle in treating addiction is a high susceptibility for relapse which persists despite prolonged periods of abstinence. Relapse can be triggered by drug predictive stimuli such as environmental context and drug associated cues, as well as the addictive drug itself. The conditioned place preference (CPP) behavioral model is a useful paradigm for studying the ability of these drug predictive stimuli to reinstate drug-seeking behavior. The present study investigated the dose-dependent effects of D-serine (10 mg/kg, 30 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg) on extinction training and drug-primed reinstatement in cocaine-conditioned rats. In the first experiment, D-serine had no effect on the acquisition or development of cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization or CPP. In the second experiment, D-serine treatment resulted in significantly decreased time spent in the drug-paired compartment following completion of an extinction protocol. A cocaine-primed reinstatement test indicated that the combination of extinction training along with D-serine treatment resulted in a significant reduction of drug-seeking behavior. The third experiment assessed D-serine’s long-term effects to diminish drug-primed reinstatement. D-serine treatment given during extinction was effective in reducing drug-seeking for more than four weeks of abstinence after the last cocaine exposure. These findings demonstrate that D-serine may be an effective adjunct therapeutic agent along with cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of cocaine addiction.

Keywords: place preference, cocaine, D-serine, extinction, reinstatement

1. Introduction

Addiction can be defined as a psychological disease that is characterized by uncontrollable, compulsive drug seeking and drug use despite negative health and social consequences (Baler and Volkow, 2006). One obstacle for the treatment of addiction is the susceptibility to relapse which can persist several years despite prolonged periods of abstinence (O’Brien, 2003). The use of preclinical animal models such as self-administration, behavioral sensitization and conditioned place preference (O’Brien and Gardner, 2005) has allowed the mechanisms that underlie the priming of reinstatement behavior to be explored. The reinstatement of drug-seeking has been observed in rats exposed to addictive substances such as psychostimulants, nicotine, ethanol and opioids, and may be triggered by drug predictive stimuli such as environmental context, stress, drug-associated cues, as well as the addictive drug itself (Shaham and Miczek, 2003).

In the treatment of anxiety disorders, exposure therapy has been shown to be an effective treatment for reducing the frequency and intensity of episodes (Otto et al., 2004). The N-Methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor has been implicated as being involved in extinction learning (Falls et al., 1992), and several conditioned fear studies illustrate that antagonism of NMDA receptors during extinction impairs the effects of such training (Myers and Carlezon, 2010). In a complementary manner, enhancement of NMDA receptor activity with D-cycloserine, a partial agonist at the glycine site of the NMDA receptor, facilitates fear extinction (Walker et al., 2002). The translational success of this line of investigation from an understanding of preclinical mechanisms in animals to promising clinical results in humans has prompted a strong interest in using a similar rationale for the treatment of addiction, but the effectiveness of exposure therapy in this context has been unclear (Conklin and Tiffany, 2002).

Using a cocaine self-administration model, we have previously described a requirement for NMDA receptor activity during extinction training to reduce subsequent drug-primed reinstatement (Kelamangalath et al., 2007). In addition, we have examined the actions of D-serine, a full agonist at the glycine modulatory site of the NMDA receptor and its effects on cocaine-primed reinstatement. By employing sub-optimal extinction protocols in rats allowed either limited access (Kelamangalath et al., 2009) or extended access (Kelamangalath and Wagner, 2010a) to cocaine self-administration, the enhancing effects of D-serine treatment during or immediately following extinction training resulted in reduced drug-primed reinstatement. This only occurred when D-serine is given in conjunction with extinction training; a finding also reported using D-cycloserine (Dhonnchadha et al., 2010).

D-cycloserine is effective in facilitating cocaine-induced conditioned place preference (CPP) in both rats and mice (Botreau and Stewart, 2006; Thanos et al., 2009). As is the case for self-administration, CPP behavior can be extinguished and reinstated following drug-priming, stress, or conditioned cues (Tzschentke, 2007). A significant feature of the CPP protocol is the practical advantage of being able to test relatively large numbers of animals that allow dose-response studies to be efficiently conducted. The present study was designed to investigate the dose-dependent effects of D-serine (10 mg/kg, 30 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg) on extinction and drug-primed reinstatement in cocaine-conditioned rats. When combined with extinction training, D-serine was effective in facilitating extinction and in reducing cocaine-primed reinstatement; an effect that persisted for more than 4 weeks. These results suggest that D-serine is a promising adjunct treatment to be combined with exposure therapy for the treatment of cocaine addiction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Drugs

D-serine was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Cocaine hydrochloride was obtained from NIDA (RTI International, NC, USA).

2.2 Animal Maintenance

Sprague–Dawley male rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) were housed in pairs in clear plastic cages. They were maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle (0700 hr/1900 hr) with food and water available ad libitum. Animals were allowed to acclimate to their home cages for one week and were habituated to handling for 3 days before behavioral testing began. Sessions were conducted daily between 0900hr and 1500hr. These studies were approved by the University of Georgia Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.3 Apparatus

Gosnell (2005) gave a detailed account of the chambers and its dimensions. Behavioral testing was carried out in 43.2 × 43.2 cm chambers with clear plastic walls and a solid smooth floor (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT, USA). Each chamber was housed in a sound-attenuating box equipped with two house lights (20 lx) and a ventilation fan. Two banks of 16 infrared photo beams and detectors detected horizontal activity. Activity Monitor software (Med Associates) was used to count beam breaks.

Conditioned place preference (CPP) testing occurred in a two compartment insert (Med Associates) that modified the open field chamber. The modified chamber was divided into two identical compartments (42.8 × 21.3 cm) separated by a black partition containing a guillotine door. When the guillotine door was removed, the rat had access to the entire chamber and was put in place to confine the animal’s activity to one compartment during conditioning. The compartments differed by floor type (grid, wire mesh vs. rod, steel bars) and by ceiling color (transparent vs. black). The compartment with the rod-floor had the black ceiling which darkened that side of the chamber insert; preliminary studies indicated that this arrangement yielded an equal preference between compartments.

2.4 Experimental design

2.4.1 Experiment 1

Seymour and Wagner (2008) describe in detail the experimental design of our first set of experiments. Rats were tested in a Pretest session (protocol day 1) where each animal was placed in the light/grid compartment and allowed free access to both compartments of the CPP chamber for 15 min (Fig. 1A). The time spent in each compartment was analyzed to assure that none of the animals had a strong bias toward either side of the compartment. Any rat spending >65% of its time in either compartment was excluded from this unbiased CPP study. The following day the place preference inserts were removed and rats were placed in the center of the open field chamber for 30 minutes to monitor baseline activity (Activity, protocol day 2). An i.p. injection of either 0.9% saline (n=45) or cocaine (10 mg/kg, n=34) was given and the animal was placed back in the open field where activity was monitored for an additional 60 minutes.

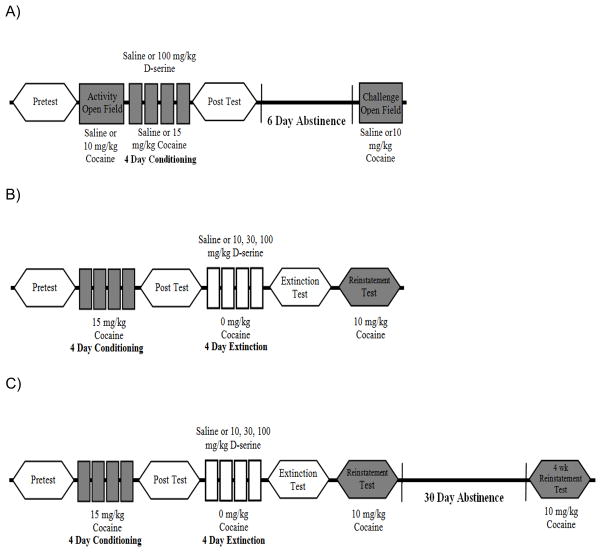

Figure 1. Experimental designs employed in this study.

Open polygons represent drug-free place preference testing, filled polygons represent cocaine-primed (10 mg/kg) reinstatement place preference testing. Squares represent open-field testing in a distinct chamber environment, during which either saline or cocaine (10 mg/kg) are administered. Filled rectangles represent conditioning sessions to either saline or cocaine (15 mg/kg), open rectangles represent extinction sessions (saline only). See Materials & Methods for additional details.

Conditioning sessions began the next day (protocol days 3–6). Saline-paired and cocaine-paired animals were given either an i.p. injection of saline or 100 mg/kg of D-serine 1–2 hours prior to conditioning sessions, in the home cage. In all, four groups were tested saline/saline (n=29), saline/cocaine (n=24), D-serine/saline (n=16), and D-serine/cocaine (n=10). Rats were placed in one of the two compartments for 15 minutes and then returned to their home cage. Four hours later, animals were injected with either saline or cocaine and confined to the opposite compartment for the second daily conditioning session. Following the completion of conditioning, a second drug-free place preference test was administered (Post Test, protocol day 7). One week later, the open field Challenge test (protocol day 13) was conducted in the same manner as the Activity test to assess sensitization.

2.4.2 Experiment 2

The protocol for Experiment 2 (Fig. 1B) did not include open field assessments of locomotor activity. Following the CPP Pretest, cocaine conditioning proceeded with saline and cocaine (15mg/kg) pairings as previously described, except no home cage pretreatments occurred. Following the CPP Post Test, a passive extinction protocol (days 7–10) was carried out in which groups received their respective treatments of saline (n=10), 10 mg/kg D-serine (n=6), 30 mg/kg D-serine (n=7), or 100 mg/kg of D-serine (n=14) immediately before being confined to their former cocaine-paired compartment. As with during the conditioning phase, animals were also confined to the opposite compartment and given the vehicle treatment (saline) immediately prior to the second extinction session. Following the end of extinction training, a third CPP test was conducted (Extinction Test, protocol Day 11). Animals were placed in their saline-paired compartment and explored the CPP chamber for 15 minutes. The next day, all rats were given an i.p. injection of 10 mg/kg cocaine and again placed in their saline-paired compartment to explore the CPP chamber for 15 minutes (Reinstatement Test, protocol day 12).

2.4.3 Experiment 3

Experiment 3 followed the exact procedures of experiment 2 except some of the former rats were held abstinent in their home cage environment for an additional 30 days following the Reinstatement Test. On protocol day 43, a second reinstatement test (4 wk Reinstatement Test) was conducted. Once again, all animals received an i.p. injection of 10 mg/kg of cocaine immediately prior to being placed into the saline-paired compartment of the CPP chamber and allowed free access for 15 minutes. Two combined groups were analyzed in this experiment, a saline & 10 mg/kg group, n = 11; and a 30 & 100 mg/kg group, n =16.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

Statistics were done using SigmaStat software, version 3.1. One-way repeated measures (RM) ANOVAs were used to analyze time spent in the drug-paired compartment across multiple CPP tests and one-way ANOVAs were used to analyze between groups for the shift in preference, locomotor activity, and locomotor sensitization results. Post-hoc analysis used in all cases was Holm-Sidak.

3. Results

3.1 Experiment 1 (Fig. 1A) The effects of pretreatment with systemic D-serine on locomotor activity and the development of conditioned place preference or locomotor sensitization

3.1.1 D-serine pretreatment does not affect the response to a novel environment or cocaine

D-serine has undergone substantial testing as an antipsychotic agent in human trials (Tsai et al., 1998) and investigated for activity in several preclinical rodent models of schizophrenia (reviewed by (Labrie et al., 2012). However in some respects, relatively little characterization of the behavioral effects of D-serine has been reported in preclinical studies. For example, the measurement of locomotor behavior is used extensively in the assessment of rewarding and sensitizing properties of drugs of abuse such as cocaine (Kalivas et al., 1993; Steketee and Kalivas, 2011). Although D-serine alone does not have obvious behavioral consequences when administered i.c.v. (Contreras, 1990) or systemically (Labrie et al., 2009), the potential interactive effects of systemic D-serine on measures such as the acquisition and development of cocaine-induced sensitization or CPP have not been described.

Following the protocol for the first experiment (Fig. 1A), 4 groups of rats were pretreated with either saline (n=29 saline group, n=24 cocaine group) or D-serine (100 mg/kg; n=16 saline group, n=10 cocaine group) in their home cage 1–2 hr prior to exposure to their first conditioning session on day 3. D-serine pretreatment had no effect on the locomotor responses of either saline- or cocaine-treated rats when they were introduced into the conditioning environment (Fig. 2A, gray bars vs. their corresponding white/black bars). As expected, cocaine (15 mg/kg)-induced a significant increase in locomotor activity that was evident in both treatment groups (saline vs cocaine, ** p < 0.01 and D-serine/saline vs. D-serine/cocaine, * p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak).

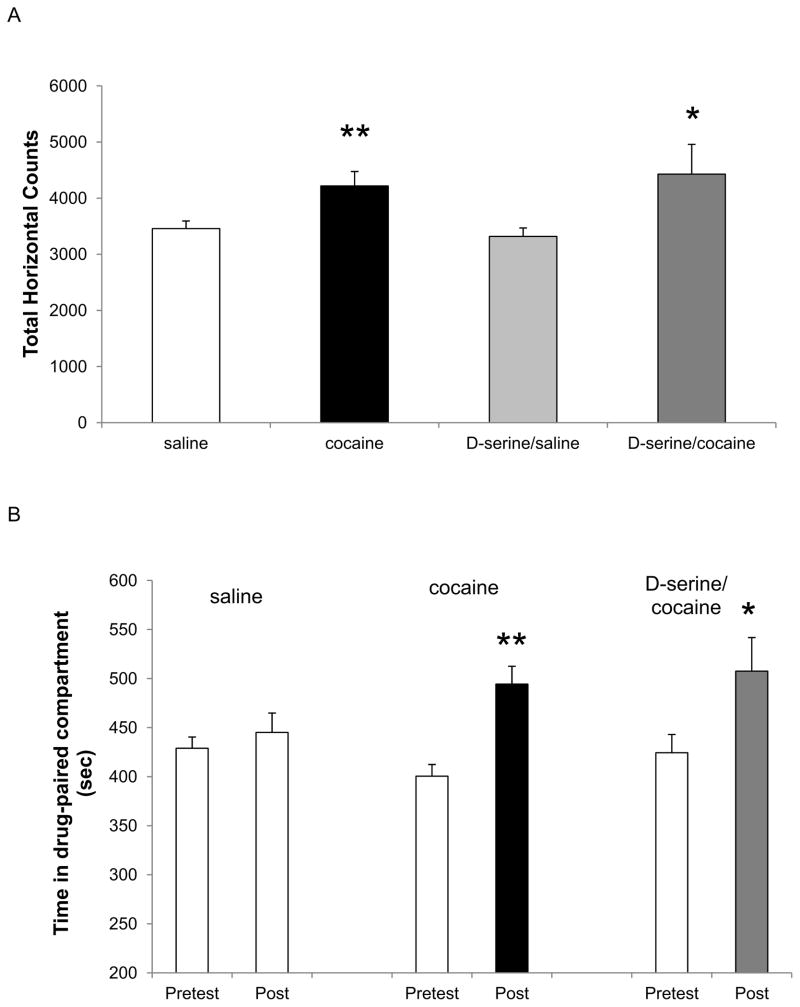

Figure 2. D-serine pretreatment does not affect the acquisition of cocaine-induced CPP.

A) On the first of day of cocaine conditioning, pretreatment with D-serine (100 mg/kg) does not affect either the baseline locomotor behaviour in the saline-paired compartment or the cocaine-induced increase in locomotor behaviour. Cocaine significantly increased activity in both saline and D-serine groups (** p<0.01 and * p<0.05, one-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak). B) Following the completion of the conditioning protocol, a significant increase in the time spent in the cocaine-paired compartment was evident during the CPP Post test as compared to the Pretest. Pretreatment with D-serine prior to the conditioning sessions did not significantly affect the acquisition of CPP expressed during the Post test (** p<0.01 and * p<0.05, one-way RM ANOVA/Holm-Sidak).

3.1.2 D-serine pretreatment does not affect the development of cocaine-induced place preference

Cocaine-induced CPP following a total of four such conditioning protocol days was assessed on protocol day 7 by allowing the animal free choice between the cocaine/saline conditioning environments while in a drug-free state. Under these conditions, cocaine-conditioned rats (middle pair of bars) exhibited the expected significant shift in time spent in the drug-paired compartment (** p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak), whereas saline-conditioning (left pair of bars) had no significant effect (Fig. 2B). Rats pretreated with D-serine prior to each conditioning session (protocol days 3–6) also exhibited a significant shift in time spent in the cocaine-paired environment during the post conditioning test (right pair of bars, * p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak).

3.1.3 D-serine pretreatment does not affect the development of cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization

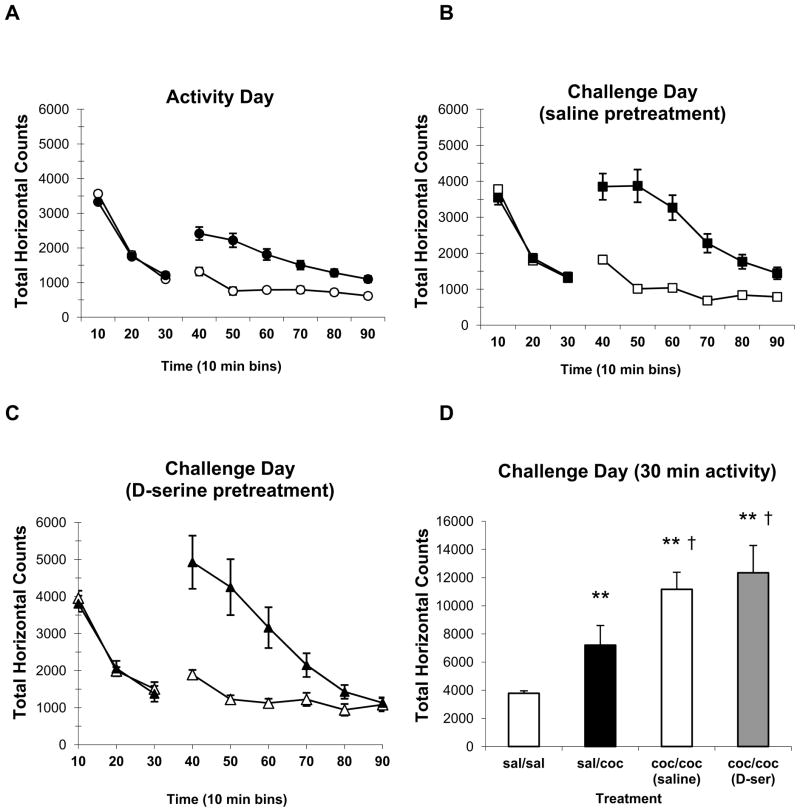

The effects of D-serine pretreatment on the acquisition and development of locomotor sensitization were assessed on protocol day 13, one-week following the last cocaine conditioning session. At this time, the cocaine-induced enhancement of locomotor activity was further increased in the cocaine-conditioned, saline pretreatment rats compared with the initial response to cocaine from the protocol day 2 activity test (Fig. 3A vs. 3B). Similarly, the cocaine-induced enhancement of locomotor activity was further increased in the cocaine-conditioned D-serine pretreated rats compared with the initial response to cocaine from the protocol day 2 activity test (Fig. 3A vs. 3C). A summary analysis from the Challenge day test groups (Fig. 3D) indicates that both saline and D-serine pretreatment cocaine groups were significantly sensitized as compared with the saline-conditioned group receiving cocaine for the first time on the Challenge Day († p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak). There was no significant difference between the cocaine-induced sensitization of the locomotor response observed between the saline or D-serine pretreatment groups.

Figure 3. D-serine pretreatment does not affect the acquisition of cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization.

A) Locomotor activity was increased following i.p. administration of cocaine (10 mg/kg) compared with saline injection at t=30 min of the 90 minute Activity Open Field session. The cocaine group (filled circles) was subsequently split into the saline (panel B, filled squares) and D-serine (panel C, filled triangles) pretreatment groups. B) Following four days of conditioning, saline pretreated rats exhibited the expected increase in locomotor response to cocaine when retested one week post conditioning during the Challenge Open Field session. C) The response to cocaine was similarly enhanced in the D-serine (100 mg/kg) group that was pretreated prior to each of the four condition sessions. D) Summary data from the Challenge Open Field test in which the first 30 minutes post injection locomotor activity is depicted from four test groups of rats: The saline conditioned, cocaine tested (sal/coc) group was conditioned with saline and received cocaine for the first time during the Challenge Open Field test. Cocaine induced a significant increase in activity as compared with the saline conditioned, saline tested (sal/sal) control group (** p<0.01, one-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak). Both of the cocaine conditioned groups (coc(saline)/coc & coc(D-ser)/coc) exhibited a significant increase in activity as compared with the sal/sal control group (** p<0.01, one-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak) and activity was also increased as compared to the sal/coc group († p<0.05, one-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak).

3.2 Experiment 2 (Fig. 1B) The influence of D-serine on the effectiveness of extinction and cocaine-primed reinstatement of CPP

3.2.1 Test groups exhibited similar conditioning chamber preference (Pretest) and response following cocaine conditioning (Post Test)

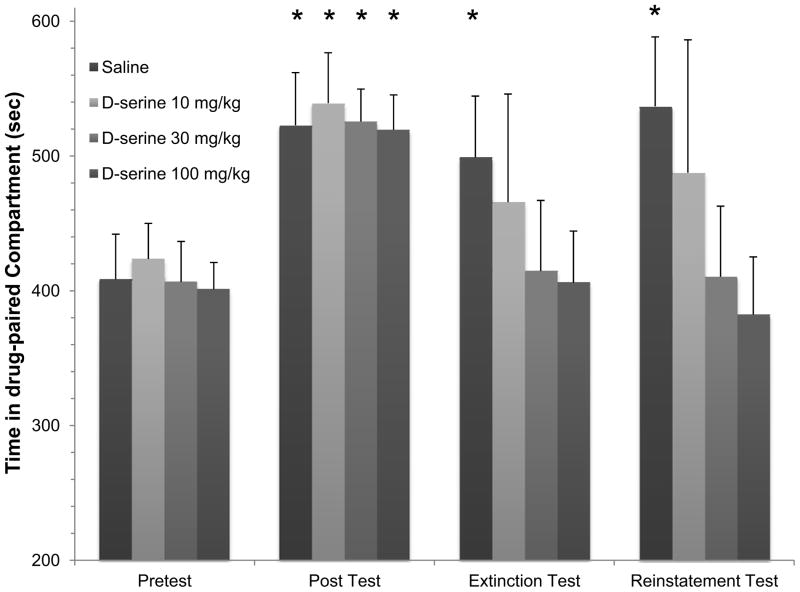

Rats were placed into the CPP chamber for the first time and time spent in each compartment was measured (Fig. 4, Pretest). After four days of conditioning with cocaine, time spent in the drug-paired compartment significantly increased (* Post Test, one-way RM ANOVA F(1, 59) = 187.846, * p < 0.01). The animals were then split into four treatment groups; Control (n=10), D-serine 10 mg/kg (n=6), D-serine 30 mg/kg (n=7), and D-serine 100 mg/kg (n=14) for extinction and reinstatement studies. In our previous reports describing the actions of D-serine to enhance the effectiveness of extinction training to reduce drug-primed reinstatement in self-administering rats, it was important to employ a modest extinction protocol that allowed the effects of D-serine to be evident (Kelamangalath et al., 2009; Kelamangalath and Wagner, 2010a). In the current saline group, one-way RM ANOVA analysis revealed that the cocaine-induced CPP was maintained throughout extinction training (Extinction Test, * p <0.01, one-way RM ANOVA/Holm-Sidak) as well as following drug-primed reinstatement (Reinstatement Test, p <0.01, one-way RM ANOVA/Holm-Sidak).

Figure 4. Illustration of time spent in drug-paired compartment between treatment groups and across tests.

Cocaine-conditioning increased time spent in the drug-paired compartment in all groups (* p<0.05 one-way RM ANOVA/Holm Sidak). The cocaine-induced CPP was maintained following extinction and during cocaine-primed reinstatement testing the in the saline group, demonstrating the sub optimal nature of the extinction training protocol alone.

3.2.2 D-serine dose-dependently enhanced extinction training, reducing the shift in preference for the cocaine-paired compartment (Extinction Test)

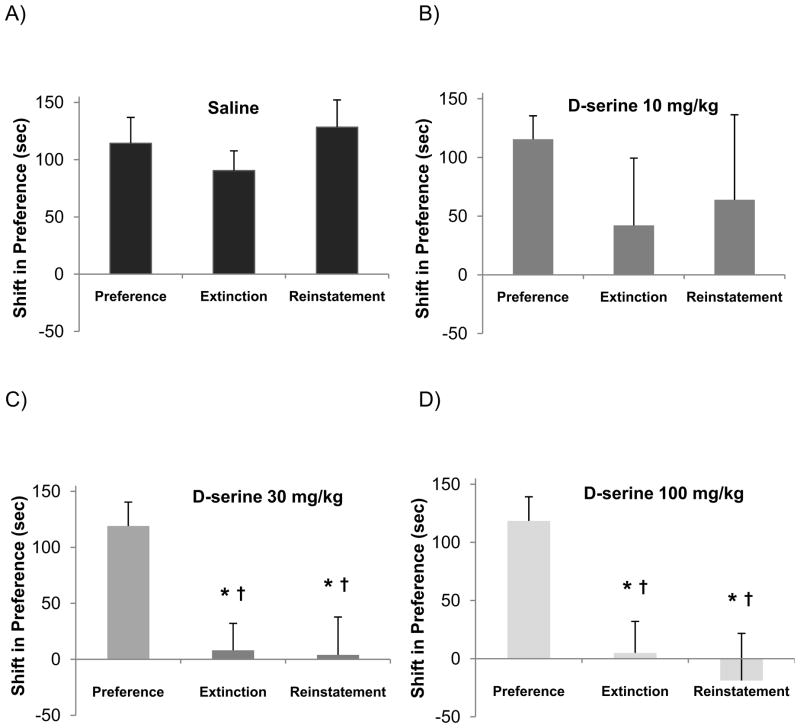

Rats were treated each day during the extinction phase of the protocol (days 7–10) with either saline or D-serine immediately before being placed into the former cocaine-paired compartment of the conditioning chamber. A dose-dependent decrease in time spent in the drug-paired compartment was evident that persisted during reinstatement testing (Fig. 4). In order to facilitate comparisons between treatment groups, the results were expressed as the cocaine-induced shift in time spent in the drug-paired compartment (Fig. 5). Following extinction training, a significant shift in preference was observed in the 30 mg/kg D-serine group (* p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak, Fig. 5C), and this effect was also significant in comparison to the saline group extinction results († p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak, Fig. 5A vs. 5C). Similarly, a significant shift in preference was observed following extinction training in the 100 mg/kg D-serine group (* p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak, Fig. 5D), and this effect was significant in comparison to the saline group extinction results († p <0.01, one-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak, Fig. 5A vs. 5D). In both the saline group and the 10 mg/kg D-serine group there was not a significant shift in preference after extinction training (e.g. Fig. 5A & 5B). Taken together, these results suggest that under conditions in which extinction alone is insufficient to reduce cocaine seeking, D-serine treatment was able to enhance extinction in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 5. D-serine decreases preference shift in a dose-dependent manner.

D-serine, when given at doses 30 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg significantly reduced the animals preference for their drug-paired compartment both after extinction training and following cocaine-primed reinstatement when compared to the preference test (* p<0.05, one-way ANOVA/Holm Sidak). Comparisons to the respective saline Extinction and Reinstatement group results were also significant († p<0.05, one-way ANOVA/Holm Sidak).

3.2.3 Cocaine-primed reinstatement was reduced in animals treated with either 30 mg/kg or 100 mg/kg of D-serine (Reinstatement Test)

A drug-primed Reinstatement Test (protocol day 12) was administered to assess the effects of D-serine treatment. Following cocaine-priming (10 mg/kg), a significant shift in preference was observed in the 30 mg/kg D-serine group (* p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak, Fig. 5C), and this effect was also significant in comparison to the saline group reinstatement results († p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak, Fig. 5A vs. 5C). Once again, a significant shift in preference was observed following reinstatement in the 100 mg/kg D-serine group (* p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak, Fig. 5D), and this effect was significant in comparison to the saline group reinstatement results († p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA/Holm-Sidak, Fig. 5A vs. 5D). In both the saline group and the 10 mg/kg D-serine group there was not a significant shift in preference (e.g. Fig. 5A & 5B). Altogether, D-serine treatment (either 30 mg/kg or 100 mg/kg) during extinction training was able to subsequently reduce drug-primed reinstatement.

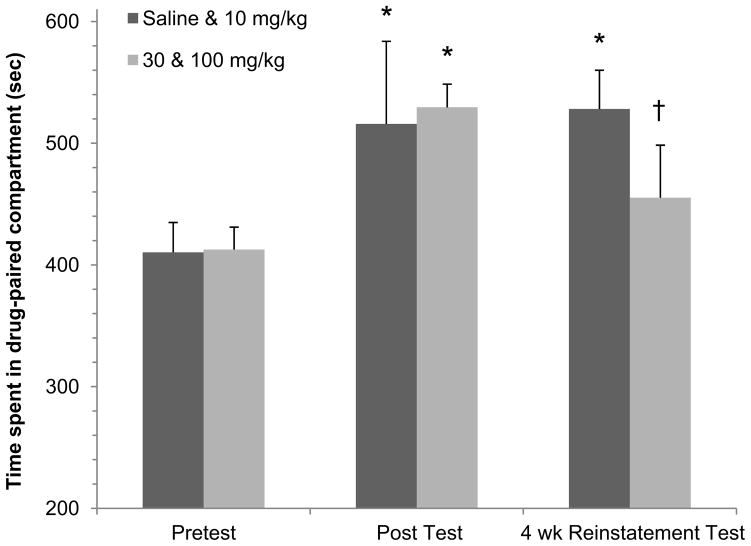

3.3 Experiment 3 (Fig. 1C) The effects of D-serine treatment 4 weeks after final cocaine exposure

D-serine’s effectiveness in reducing drug-primed reinstatement is persistent, lasting more than 4 weeks (Fig. 6). In a subset of animals, a second cocaine-primed reinstatement test was given approximately 4 weeks after the first reinstatement test (protocol day 12) on protocol day 43. During the abstinent period the rats remained in their home cage environment. In order to increase the overall statistical power, we collapsed the four treatment groups into two groups for analysis. Given that the saline and 10 mg/kg D-serine groups exhibited similar results in Experiment 2 (c.f. Fig. 5A & 5B); we collapsed these two groups into one analysis group (saline & 10 mg/kg D-serine, n=11). Similarly, as both the 30 mg/kg and the 100 mg/kg D-serine data were also comparable (c.f. Fig. 5C & 5D); we combined the 4 week reinstatement results of these two groups into a “30 & 100 mg/kg” analysis group (n=16).

Figure 6. 4-week Reinstatement in combined groups.

Cocaine-induce CPP for the drug-paired compartment was evident in both the saline & 10 mg/kg D-serine combined group as well as the 30 &100 mg/kg D-serine combined group (* p<0.05, Pretest vs. Post Test, one-way RM ANOVA/Holm-Sidak, respectively). This significant increase in time spent in the drug-paired compartment was maintained following the 4 week abstinent period in the saline & 10 mg/kg D-serine group as compared to the Pretest (* p < 0.05, one-way RM ANOVA/Holm-Sidak). In contrast, the increase in time spent of the combined 30 & 100 mg/kg D-serine group was no longer significant at the 4 wk Reinstatement Test, and the time spent in the drug-paired compartment was significantly decreased as compared to that of the saline & 10 mg/kg D-serine group († p<0.05, one-way ANOVA/Holm Sidak).

As expected from the results depicted in Fig. 4, cocaine-induce CPP for the drug-paired compartment was evident in both the saline & 10 mg/kg D-serine combined analysis group as well as the 30 &100 mg/kg D-serine combined analysis group after cocaine-priming (* p<0.05, Pretest vs. Post Test, one-way RM ANOVA/Holm-Sidak, respectively). For the saline & 10 mg/kg D-serine group, this significant shift in preference was maintained following the abstinent period in the 4 wk Reinstatement Test (* p < 0.05, one-way RM ANOVA/Holm-Sidak). In contrast, the combined 30 & 100 mg/kg D-serine group CPP was no longer maintained to a significant extent at the 4 wk Reinstatement Test. Furthermore, the time spent in the drug-paired compartment was significantly decreased in this analysis group as compared to that of the saline & 10 mg/kg D-serine group († p<0.05, one-way ANOVA/Holm Sidak). Together these findings indicate that the effects of D-serine treatment during extinction training to reduce drug-primed reinstatement can persist more than 4 weeks following the last extinction session or previous cocaine exposure.

4. Discussion

The primary result of the present study is that systemic administration of D-serine immediately prior to extinction sessions can subsequently facilitate the effects of such training to decrease drug-seeking during a cocaine-primed reinstatement test. D-serine exhibited dose-dependent effects, with the effective D-serine doses of 30 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg being quite modest relative to those used in other behavioral studies (Duffy et al., 2008; Karasawa et al., 2008), an important finding given the nephrotoxicity known to occur in rodents following exposure to doses in excess of 100/mg/kg (Williams et al., 2003). The extinction protocol used in our experiments was insufficient to significantly reduce cocaine-seeking, however in combination with 30 mg/kg or 100 mg/kg of D-serine the effects of the behavioral training were enhanced and a persisting reduction in drug-primed reinstatement was observed. Importantly, this effect of D-serine persisted for more than 4 weeks following the final treatment session. The potential importance of these findings with respect to the therapeutic potential of D-serine is discussed below.

Mechanisms involved in learning and memory of extinction training and the mechanisms involved in reinstatement have been extensively studied in paradigms such as fear conditioning, conditioned taste aversion, and inhibitory avoidance (Cammarota et al., 2005). For example, the partial NMDA receptor agonist D-cycloserine has been found to facilitate conditioned fear responses (Bouton et al., 2008; Ledgerwood et al., 2004; Walker et al., 2002). D-cycloserine has also been used in CPP models of cocaine-seeking to enhance extinction training (Botreau and Stewart, 2006; Thanos et al., 2009). Contrary to these results, other published work reports that D-cycloserine given 30 minutes prior to extinction training slowed the rate of extinction (Port and Seybold, 1998), and infusion of D-cycloserine in the basalateral amygdala increased cue-induced relapse (Lee et al., 2009) in cocaine-conditioned rats. In cocaine-conditioned mice a dose of 30 mg/kg D-cycloserine resulted in renewed CPP at 2 weeks (Thanos et al., 2009). Morphine-conditioned rats treated with D-cycloserine at doses of 7.5 mg/kg, 15 mg/kg and 30 mg/kg had no effects on extinction or the expression of morphine-induced CPP (Lu et al., 2011). In addition, the use of D-cycloserine as an adjunctive treatment for addiction has been tested in several clinical trials producing a wide range of conclusions, including that D-cycloserine facilitates extinction in nicotine-dependent smokers (Ana et al., 2009; Santa Ana et al., 2009). D-cycloserine increases craving in cocaine-dependent individuals (Hofmann SG, 2012; Price KL, 2012; Price et al., 2009) as well as in heavy alcohol drinkers (Hofmann SG, 2012) and D-cycloserine has no effect on cue-reactivity in alcohol-dependent individuals (Watson et al., 2011). Thus, the use of D-cycloserine has yielded mixed results with respect to its potential use for the treatment of addiction. Assuming that the positive influence of this agent on learning/memory performance is due to its enhancement of NMDA receptor activity and the associated NMDAR-dependent learning, the examples of a negative influence may also be derived from the inhibitory effects that a partial agonist at this modulatory site may have under certain circumstances.

D-serine is different from D-cycloserine in that it acts as a full agonist at the glycine modulatory site of the NMDA receptor (Furukawa and Gouaux, 2003). Krystal et al (2011) found that when D-cycloserine was given to healthy individuals in the presence of increased levels of glycine, it produced effects similar to those of NMDA receptor antagonists at low doses (Dickerson et al., 2010). Therefore, it is possible that in individuals with a relatively high basal level of glycine or D-serine activity, D-cycloserine may act in a competitively antagonistic manner rather than enhancing the activity of the NMDA receptor. This antagonism would not occur with the full agonist, D-serine. In addition, D-serine is an endogenously produced amino acid and the brain contains mechanisms for its degradation (Schell et al., 1995). Thus as a practical consideration for the therapeutic use of D-serine, these endogenous synthetic and degradative mechanisms and their regulation may help to protect against toxicity. For example, a high-dose D-serine regime of 60 mg/kg in a recent human trial has been described as being well tolerated (Kantrowitz et al., 2010). In the current study, we found that pretreatment with 100 mg/kg D-serine does not affect locomotor activity during cocaine conditioning, and it does not interfere with the acquisition or development of either cocaine-induced sensitization or CPP. Therefore, the described effects of D-serine in our studies are not consistent with any direct interaction with cocaine or its behavioral consequences, and are instead consistent with its activity as an agonist at the glycine modulatory site and the enhancement of NMDA receptor-dependent learning during extinction training.

When tested in cocaine self-administration reinstatement protocols, D-serine treatment along with extinction training results in a significant reduction of drug-primed reinstatement in rats with a history of either short or long access to drug (Kelamangalath and Wagner, 2009, 2010b). An important feature of these studies was that the effect of extinction training was suboptimal, meaning that a significant reduction in drug-primed reinstatement was not observed with extinction alone. This was also the circumstance in the current report, as extinction training in the saline-treated rats was not effective in significantly diminishing the cocaine-induced CPP. However, when D-serine was combined with such training, CPP was completely eliminated in either the 30 mg/kg or 100 mg/kg treatment doses. This demonstrates an important feature of this adjuvant pharmacotherapy-the capacity to enhance an otherwise weak or ineffective behavioral protocol without increasing the number of training sessions or their duration. This is a potentially significant therapeutic advantage, as it may not be practical for treatment seeking individuals to attend sessions at greater frequency or of longer duration. Thus promising cognitive behavioral therapy protocols may achieve clinical efficacy when combined with D-serine treatment.

Importantly, we found that D-serine pretreatment before extinction training not only facilitated extinction and reduced cocaine-primed reinstatement tested 2 days later, but it also exhibited much longer effects in reducing drug-primed reinstatement for more than 4 weeks. These results are in general agreement with the conclusions of Paolone et al (2009), as they found D-cycloserine reduced drug-primed reinstatement assessed 25 days after the last extinction training session. These observations highlight another feature of practical importance regarding the potential use of D-serine along with behavioral therapy, that the interval between the “booster” sessions required for the ongoing maintenance of the extinguished condition can be lengthened. For example, monthly treatments involving a day or two are more likely to be amenable for the typical patient than would ongoing weekly or multiple days/week session schedule.

5. Conclusion

D-serine, a full agonist of the NMDA receptor at the glycine co-agonist site, facilitated extinction and reduced drug-primed reinstatement of cocaine-induced CPP in rats following systemic administration. The effects of D-serine treatment during extinction resulted in a persisting reduction of cocaine-primed reinstatement for more than 4 wks. These effects were dose-dependent and the amount of D-serine effective in these studies has already been tested and well tolerated in humans for use as an antipsychotic agent. These results and observations demonstrate that D-serine could be an effective adjunct treatment along with cognitive behavioral therapy for cocaine addiction by reducing the number of initial therapy sessions and/or by increasing the interval between future maintenance therapy sessions.

Highlights.

D-serine dose-dependently facilitated the effectiveness of extinction training.

D-serine significantly reduced cocaine-primed reinstatement.

D-serine had a persisting effect (> 4wks) to reduce reinstatement.

Acknowledgments

This work supported by NIH (DA016302) to JJW, by Alfred P. Sloan Foundation to SH, and by the Georgia Veterinary Scholars Program to AB.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ana EJS, Rounsaville BJ, Frankforter TL, Nich C, Babuscio T, Poling J, Gonsai K, Hill KP, Carroll KM. D-Cycloserine attenuates reactivity to smoking cues in nicotine dependent smokers: A pilot investigation. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;104:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baler RD, Volkow ND. Drug addiction: the neurobiology of disrupted self-control. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2006;12:559–566. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botreau F, Stewart J. D-cycloserine, a NMDA agonist, facilitates extinction of a cocaine-induced conditioned place preference in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:S43–S43. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Vurbic D, Woods AM. D-cycloserine facilitates context-specific fear extinction learning. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2008;90:504–510. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammarota M, Bevilaqua LRM, Barros DM, Vianna MRM, Izquierdo LA, Medina JH, Izquierdo I. Retrieval and the extinction of memory. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology. 2005;25:465–474. doi: 10.1007/s10571-005-4009-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin CA, Tiffany ST. Applying extinction research and theory to cue-exposure addiction treatments. Addiction. 2002;97:155–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras PC. D-SERINE ANTAGONIZED PHENCYCLIDINE-INDUCED AND MK-801-INDUCED STEREOTYPED BEHAVIOR AND ATAXIA. Neuropharmacology. 1990;29:291–293. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(90)90015-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhonnchadha BAN, Szalay JJ, Achat-Mendes C, Platt DM, Otto MW, Spealman RD, Kantak KM. D-cycloserine Deters Reacquisition of Cocaine Self-Administration by Augmenting Extinction Learning. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:357–367. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson D, Pittman B, Ralevski E, Perrino A, Limoncelli D, Edgecombe J, Acampora G, Krystal JH, Petrakis I. Ethanol-like effects of thiopental and ketamine in healthy humans. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2010;24:203–211. doi: 10.1177/0269881108098612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy S, Labrie V, Roder JC. D-Serine augments NMDA-NR2B receptor-dependent hippocampal long-term depression and spatial reversal learning. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1004–1018. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falls WA, Miserendino MJD, Davis M. EXTINCTION OF FEAR-POTENTIATED STARTLE - BLOCKADE BY INFUSION OF AN NMDA ANTAGONIST INTO THE AMYGDALA. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12:854–863. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-00854.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa H, Gouaux E. Mechanisms of activation, inhibition and specificity: crystal structures of the NMDA receptor NR1 ligand-binding core. Embo Journal. 2003;22:2873–2885. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosnell BA. Sucrose intake enhances behavioral sensitization produced by cocaine. Brain Research. 2005;1031:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, HR, Mackillop J, Kantak KM. Effects of d-Cycloserine on Craving to Alcohol Cues in Problem Drinkers: Preliminary Findings. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012:101–107. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.600396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Sorg BA, Hooks MS. THE PHARMACOLOGY AND NEURAL CIRCUITRY OF SENSITIZATION TO PSYCHOSTIMULANTS. Behavioural Pharmacology. 1993;4:315–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantrowitz JT, Malhotra AK, Cornblatt B, Silipo G, Balla A, Suckow RF, D’Souza C, Saksa J, Woods SW, Javitt DC. High dose D-serine in the treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;121:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasawa JI, Hashimoto K, Chaki S. D-Serine and a glycine transporter inhibitor improve MK-801-induced cognitive deficits in a novel object recognition test in rats. Behavioural Brain Research. 2008;186:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelamangalath L, Seymour CM, Wagner JJ. D-Serine facilitates the effects of extinction to reduce cocaine-primed reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2009;92:544–551. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelamangalath L, Swant J, Stramiello M, Wagner JJ. The effects of extinction training in reducing the reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior: Involvement of NMDA receptors. Behavioural Brain Research. 2007;185:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelamangalath L, Wagner JJ. Effects of abstinence or extinction on cocaine seeking as a function of withdrawal duration. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2009;20:195–203. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32832a8f78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelamangalath L, Wagner JJ. D-SERINE TREATMENT REDUCES COCAINE-PRIMED REINSTATEMENT IN RATS FOLLOWING EXTENDED ACCESS TO COCAINE SELF-ADMINISTRATION. Neuroscience. 2010a;169:1127–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelamangalath L, Wagner JJ. D-Serine treatment reduces cocaine-primed reinstatement in rats following extended access to cocaine self-administration. Neuroscience. 2010b;169:1127–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal JH, Petrakis IL, Limoncelli D, Nappi SK, Trevisan L, Pittman B, D’Souza DC. Characterization of the Interactive Effects of Glycine and D-Cycloserine in Men: Further Evidence for Enhanced NMDA Receptor Function Associated with Human Alcohol Dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:701–710. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie V, Fukumura R, Rastogi A, Fick LJ, Wang W, Boutros PC, Kennedy JL, Semeralul MO, Lee FH, Baker GB, Belsham DD, Barger SW, Gondo Y, Wong AHC, Roder JC. Serine racemase is associated with schizophrenia susceptibility in humans and in a mouse model. Human Molecular Genetics. 2009;18:3227–3243. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie V, Wong AHC, Roder JC. Contributions of the D-serine pathway to schizophrenia. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:1484–1503. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledgerwood L, Richardson R, Cranney J. D-cycloserine and the facilitation of extinction of conditioned fear: Consequences for reinstatement. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2004;118:505–513. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JLC, Gardner RJ, Butler VJ, Everitt BJ. D-cycloserine potentiates the reconsolidation of cocaine-associated memories. Learning & Memory. 2009;16:82–85. doi: 10.1101/lm.1186609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu GY, Wu N, Zhang ZL, Ai J, Li J. Effects of D-cycloserine on extinction and reinstatement of morphine-induced conditioned place preference. Neuroscience Letters. 2011;503:196–199. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers KM, Carlezon WA. Extinction of drug- and withdrawal-paired cues in animal models: Relevance to the treatment of addiction. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2010;35:285–302. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien CP. Research advances in the understanding and treatment of addiction. American Journal on Addictions. 2003;12:S36–S47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien CP, Gardner EL. Critical assessment of how to study addiction and its treatment: Human and non-human animal models. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2005;108:18–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto MW, Smits JAJ, Reese HE. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:34–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolone G, Botreau F, Stewart J. The facilitative effects of d-cycloserine on extinction of a cocaine-induced conditioned place preference can be long lasting and resistant to reinstatement. Psychopharmacology. 2009;202:403–409. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1280-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Port RL, Seybold KS. Manipulation of NMDA-receptor activity alters extinction of an instrumental response in rats. Physiology & Behavior. 1998;64:391–393. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price KL, BN, McRae-Clark AL, Saladin ME, Desantis SM, Santa Ana EJ, Brady KT. A randomized, placebo-controlled laboratory study of the effects of D: -cycloserine on craving in cocaine-dependent individuals. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2592-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price KL, McRae-Clark AL, Saladin ME, Maria M, DeSantis SM, Back SE, Brady KT. DCycloserine and Cocaine Cue Reactivity: Preliminary Findings. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35:434–438. doi: 10.3109/00952990903384332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santa Ana EJ, Rounsaville BJ, Frankforter TL, Nich C, Babuscio T, Poling J, Gonsai K, Hill KP, Carroll KM. d-Cycloserine attenuates reactivity to smoking cues in nicotine dependent smokers: A pilot investigation. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell MJ, Molliver ME, Snyder SH. D-SERINE, AN ENDOGENOUS SYNAPTIC MODULATOR - LOCALIZATION TO ASTROCYTES AND GLUTAMATE-STIMULATED RELEASE. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:3948–3952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour CM, Wagner JJ. Simultaneous expression of cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization and conditioned place preference in individual rats. Brain Research. 2008;1213:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Miczek KA. Reinstatement - toward a model of relapse. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steketee JD, Kalivas PW. Drug Wanting: Behavioral Sensitization and Relapse to Drug-Seeking Behavior. Pharmacological Reviews. 2011;63:348–365. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanos PK, Bermeo C, Wang GJ, Volkow ND. D-Cycloserine accelerates the extinction of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference in C57bL/c mice. Behavioural Brain Research. 2009;199:345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai GC, Yang PC, Chung LC, Lange N, Coyle JT. D-serine added to antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 1998;44:1081–1089. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00279-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzschentke TM. Measuring reward with the conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm: update of the last decade. Addiction Biology. 2007;12:227–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DL, Ressler KJ, Lu KT, Davis M. Facilitation of conditioned fear extinction by systemic administration or intra-amygdala infusions of D-cycloserine as assessed with fear-potentiated startle in rats. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:2343–2351. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02343.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson BJ, Wilson S, Griffin L, Kalk NJ, Taylor LG, Munafo MR, Lingford-Hughes AR, Nutt DJ. A pilot study of the effectiveness of D-cycloserine during cue-exposure therapy in abstinent alcohol-dependent subjects. Psychopharmacology. 2011;216:121–129. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2199-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RE, Jacobsen M, Lock EA. H-1 NMR pattern recognition and P-31 NMR studies with D-serine in rat urine and kidney, time- and dose-related metabolic effects. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2003;16:1207–1216. doi: 10.1021/tx030019q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]