Abstract

To examine whether communication between the amygdala and gustatory insular cortex (GC) is required for normal performance of taste neophobia, three experiments were conducted. In Experiment 1, rats with asymmetric unilateral lesions of the basolateral amygdala (BLA) and the GC displayed elevated intake of a novel saccharin solution relative to control subjects. However, an attenuation of neophobia was not found following asymmetric unilateral lesions of the GC and medial amygdala (MeA; Experiment 2) or of the MeA and BLA (Experiment 3). This pattern of results indicates that the BLA and GC functionally interact during expression of taste neophobia and that the MeA functionally interacts with neither the BLA nor the GC. Research is needed to further characterize the nature of the involvement of the MeA in taste neophobia and to determine the function of the BLA-GC interaction during exposure to a new taste.

Keywords: Taste neophobia, Gustatory insular cortex, Basolateral amygdala, Medial amygdala, Rat

1. Introduction

Rats are reluctant to consume a novel tastant because they lack knowledge about the subsequent postingestive consequences, which could be fatal [6,7, 10,11,12,15,23,25]). This reaction is termed taste neophobia. If no aversive post-ingestive consequences ensue, consumption of the tastant increases and eventually reaches asymptote (i.e., recovery from neophobia occurs). Thus, taste neophobia prevents animals from over-consuming a possibly toxic tastant and, as such, functions as a first line defense mechanism that increases the probability of survival.

With regard to the neurocircuitry underpinning taste neophobia, the amygdala has been implicated in a number of lesion studies [1,19,22,27,29,31,35,49,74]. However, shortcomings in the experimental designs of much of the work in this literature [see 59], many of which were primarily focused on conditioned taste aversion [CTA] acquisition, preclude confident assessment of the nature of the neophobia deficit. For example, Nachman and Ashe [49] found that bilateral electrolytic lesions of the amygdala (centered in the basolateral amygdala [BLA] but also extending into adjacent regions such as the central, cortical and medial [MeA] nuclei) diminished the neophobic reaction to a novel tastant. These amygdala-lesioned animals, however, also showed lower intake of the tastant at asymptote than non-lesioned (SHAM) control subjects. Therefore, it is difficult to determine the nature of the deficit in these rats with widespread, multi-nuclei damage of the amygdala. A more recent study using bilateral, excitotoxic lesions found that BLA-lesioned (BLAX) rats drank significantly more novel saccharin (0.5%) on Trial 1 than the SHAM subjects and, importantly, that the BLAX rats showed comparable intake at asymptote as the SHAM group [40]. These results, while replicating the initial deficit of the amygdala-lesioned rats of Nachman and Ashe, indicate that intake deficits at asymptote are not found in rats with discrete, axon-sparing lesions of the BLA. The BLA is not the only area involved in taste neophobia. Lin et al. found that the same pattern of performance (elevated initial intake of the tastant and normal asymptote levels) in rats with bilateral NMDA lesions of the gustatory insular cortex (GC; see also, e.g., [16,28,30]). It is important to note that neither BLA nor GC lesions had any influence on neophobia elicited by consumption of either a novel aqueous odor (0.1% amyl acetate) or a novel trigeminal stimulus (0.01 mM capsaicin solution). Thus, the deficits shown in rats after each type of bilateral brain lesion cannot be attributed to a general insensitivity to novelty-induced fear. Rather, it would appear that the lesions selectively affected the processes underlying the detection and/or expression of taste neophobia.

Although the results of Lin et al. [40] might suggest that the BLA and GC share the same function, this analysis seems improbable because if it were the case then no taste neophobia deficit should be evident following bilateral lesions of either structure alone since the other area continues to serve the same function. Alternatively, the absence of behavioral compensation would seem to suggest that the BLA and GC operate in a functionally integrated way (i.e., they are different components in the same functional circuit). The present research was intended to further our understanding of the functional neurocircuitry that underlies taste neophobia by determining whether the BLA and GC contribute to the same process during taste neophobia or if they perform different processes, each of which is necessary for the neophobic response to a novel, potentially dangerous taste stimulus. Our experimental approach was predicated upon neuroanatomy showing that the BLA and GC have strong reciprocal connections that are primarily ipsilateral (e.g. [34,45,56,57,67,69]). Thus, we employed a crossed-disconnection strategy that prevents direct, serial communication between the two structures without destroying either structure bilaterally (e.g. [14,20,21,24,53]). If the BLA and GC functionally and serially interact then unilateral asymmetric lesions (e.g., BLA in one hemisphere and GC in the contralateral hemisphere) should cause deficits comparable to bilateral lesions of each structure alone whereas no deficit would be expected following unilateral lesions of the two structures in the same hemisphere. To the best of our knowledge, we are aware of no published work that has directly investigated the functional reliance of BLA-GC connections in taste neophobia using the cross-disconnection strategy, although the approach has been used to examine other forms of taste-related learning (e.g. [8,73]).

In addition to the BLA and GC, Lin et al. [40] also reported that bilateral lesions of the MeA attenuated taste, but not odor or trigeminal, neophobia. Given that the MeA is better known for its role in olfactory processing than taste processing (e.g. [3,36,45,55,65,68,71]), this finding was surprising. Nonetheless, it prompts questions of the same type discussed above concerning whether the BLA or GC functionally interacts with the MeA during taste neophobia. Accordingly, a total of three experiments were conducted involving asymmetric unilateral lesions of the BLA and GC (Experiment 1), the GC and MeA (Experiment 2), and the MeA and BLA (Experiment 3). To maintain comparability with our previous research, the experiments in the present study employed the same taste neophobia procedure used in Lin et al ([40]; also see [37,39]) that involved repeated exposures to a 0.5% saccharin solution in water deprived rats.

2. Material and methods

2.1 Subjects

The subjects were 114 experimentally naïve, male Sprague-Dawley rats obtained from Charles River Laboratory (Wilmington, MA). They were housed individually in steel hanging cages in a vivarium maintained with an ambient temperature of 21°C and a 12:12 light-dark cycle (light on at 0700 h). The rats had ad libitum access to food and water until the experiment started when they were deprived of water as described below. Behavioral procedures and animal care were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the University of Illinois at Chicago and conformed to the regulations of the American Psychological Association [2] and the National Institutes of Health [50].

2.2. Surgery

2.2.1. Experiment 1: BLA-GC lesions

Subjects were randomly assigned into three groups: 13 rats received unilateral lesions of the BLA in one hemisphere and GC in the other hemisphere (Group Contralateral); 13 rats received unilateral lesions of the BLA and GC in the same hemisphere (Group Ipsilateral); 11 rats served as the surgical control animals (Group SHAM). At the time of surgery, the rats were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (65–70 mg/kg; i.p.) and fixed in a stereotaxic instrument (ASI, Warren, MI) with blunt ear bars and tooth holder. After the midline incision was made, two trephine holes (~3 mm diameter) were drilled in the skull above the target areas (i.e., BLA or GC). Lesions were induced by iontophoretically infusing N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA; 0.15 M; St Louis, MO) via a glass micropipette (~70 μm tip diameter). Each neurotoxin infusion was made using a Midgard precision current source (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL) at the following coordinates (in mm): for the BLA, 5-min infusion at site 1: AP −2.0, ML ±4.8, DV −6.9 and site 2: AP −2.8, ML ±5.0, DV −7.2 [70]; for the GC, site 1, 10-min infusion at AP +1.2, ML ±5.2, DV −5.0 and site 2, 6-min infusion at AP +1.2, ML ±5.2, DV −4.3 [64]. In the Contralateral Group, a unilateral BLA lesion was made in the right hemisphere and a unilateral GC lesion in the left hemisphere of 6 rats and vice versa for the other 7 rats. In the Ipsilateral Group, 7 rats received unilateral BLA and GC lesions in the left hemisphere whereas the other 6 rats had the same lesions in the right hemisphere. Rats in the SHAM Group received similar surgical procedures to the Contralateral (n = 6) or the Ipsilateral Group (n = 5) with the exception that no NMDA was infused. Throughout the surgical procedure, body temperature was monitored with a rectal thermometer and maintained at ~36.5°C with a heating pad (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). All rats were returned to their home cages after recovering from anesthesia.

2.2.2. Experiment 2: GC-MeA lesions

Employing the same surgical procedures as those described in Experiment 1, three groups of subjects were prepared. Rats in Group Contralateral (n = 14) received unilateral lesions of the GC and MeA in opposite hemispheres; rats in Group Ipsilateral (n = 13) received unilateral lesions of the GC and MeA in the same hemisphere; rats in Group SHAM (n = 11) served as the surgical control subjects. Using the parameters of Lin et al. [40], MeA lesions were placed using stereotaxically-guided iontophoresis applications of NMDA at the following coordinates (in mm): 6-min infusions at site 1: AP −2.0, ML ±3.1, DV −8.3 and site 2: AP −3.0, ML ±3.4, DV −8.5.

2.2.3. Experiment 3: MeA-BLA lesions

Using the surgical techniques describe above, excitotoxic lesions were made in the MeA and BLA in Group Contralateral (n = 14) and Group Ipsilateral (n = 14); SHAM (n = 11) subjects were prepared as in Experiment 1.

2.3. Apparatus

All experimental manipulations occurred in the home cages. Fluids were presented in inverted 100-ml Nalgene graduated cylinders with silicone stoppers and steel drinking tubes. Fluid consumption was recorded to the nearest 0.5 ml.

2.4. Procedure

2.4.1 Experiment 1

Following recovery from surgery, the rats were acclimated to a deprivation schedule that permitted 15 min access to water each day during the light cycle. When intake stabilized (~10 days), neophobia trials began. Each trial involved 15-min access to 0.5% saccharin (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) and occurred every third day. A 15-min water trial was given on each of the two intervening days. Volume of fluid consumed served as the dependent measure.

2.4.2 Experiment 2

As described above for Experiment 1.

2.4.3 Experiment 3

As described above for Experiment 1.

2.5. Histology

Once the experimental procedures were completed, the lesioned rats were injected with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (~100 mg/kg) and perfused transcardially with physiological saline and 4% buffered formalin. The brains were extracted and stored in 4% formalin for at least two days and then switched to 20% sucrose for an additional two days. Thereafter, the brains were frozen, sliced at 50 μm on a cryostat (Microm, Inc. MN), and stained with crystal violet. Photographs were taken using a light microscope (Zeiss Axioskop 40) connected to a computer running Q-capture software (Quantitative Imaging Corporation, Burnaby, BC, Canada).

2.6 Statistics

For each experiment, fluid intake was analyzed with a mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Group (SHAM, Contralateral, Ipsilateral) as the between-subject factor and Trial (1 – 5) as the within-subject variable. To further characterize any obtained significant main effect or interaction, post hoc analysis (simple main effect with adjusted error term taken from the overall ANOVA) were conducted. All analyses were conducted with the help of the software of Statistica (6.0; StatSoft, Tulsa, OK), and the significant p value was set at 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Anatomical

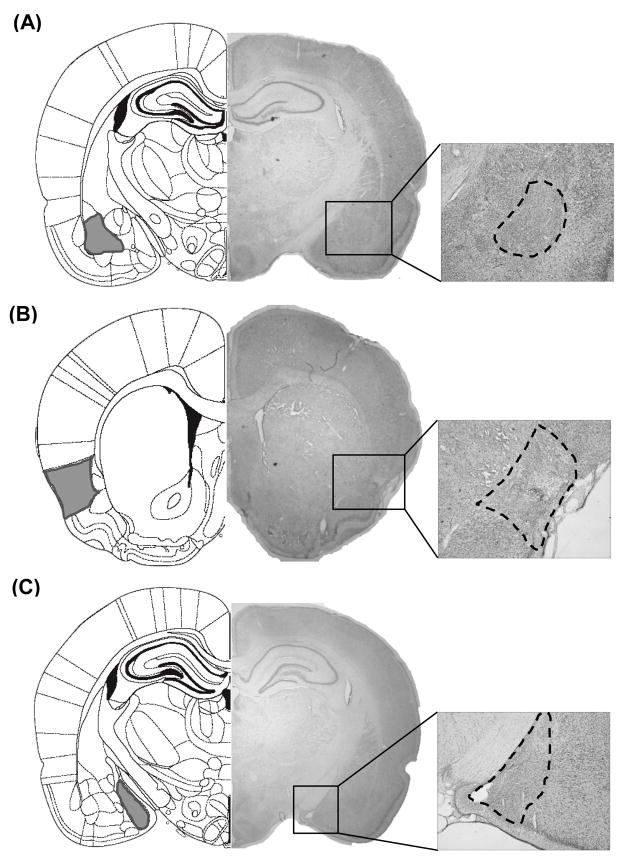

Representative NMDA lesions in the BLA, GC, and MeA are shown in Figure 1. To determine the location and size of lesions in each area, histological analyses were conducted by examining for the presence of gliosis and the absence of cell. As inspection of Figure 1A shows, the lesions were centered in the BLA and extended dorsally into the lateral amygdala. In some rats, some minor damage was found in the lateral portion of the central nucleus of the amygdala as well as the dorsal endopiriform nucleus, but these encroachments were minor and not consistently found. Panel 1B shows a representative GC lesion. In most case, these lesions were primarily located in the gustatory portion of the cortex, which is dorsal to the rhinal fissure and runs ~0.5 mm dorsoventrally and ~2.5 mm anteroposterially [33]. In some rats, lesions encroached into the surrounding areas, such as somatosensory cortex, claustrum, and piriform cortex. For MeA lesions (see Figure 1C), damage encompassed both the dorsal and ventral sub-nuclei of the MeA with minimal encroachment into the anterior portion of the basomedial amygdala and anterior cortical amygdala. Rats with subtotal lesions were excluded from further analyses. After histological examination, the final numbers of rats in each experiment were as follows. In Experiment 1, Group SHAM: n = 11, Group Ipsilateral: n = 10, Group contralateral: n = 9; In Experiment 2, Group SHAM: n = 11, Group Ipsilateral: n = 9, Group contralateral: n = 11; In Experiment 3, Group SHAM: n = 11, Group Ipsilateral: n = 13, Group contralateral: n = 10.

Fig. 1.

Photomicrographs of cresyl violet-stained sections of representative NMDA lesions in the basolateral amygdala (BLA; Panel A), gustatory insular cortex (GC; Panel B), and medial amygdala (MeA; Panel C). The area surrounded by dashed line indicates the extent of the lesion. On the left side of each panel are the correspondent schematic figures adapted from Paxinos and Watson [54] with the area of interest highlighted in gray.

3.2. Behavioral

3.2.1. Experiment 1: BLA-GC lesions

Baseline water data (averaged across the three water trials prior to the first neophobia trial) are summarized in Table 1. A two-way ANOVA found no significant main effects of Lesion (p > 0.25) or Day (F < 1) and no significant Lesion x Day interaction (p > 0.25). Thus, neither ipsilateral nor contralateral lesions of the BLA and GC had any influence on water intake.

Table 1.

Baseline water consumption (ml) from Experiments 1, 2 and 3. Data are the mean (±SE) intakes from the final three water days before the first taste trial for the neurologically intact rats (Group SHAM) and for subjects with either ipsilateral (Group Ipsilateral) or contralateral (Group Contralateral) lesions.

| Group | Experiment 1 | Experiment 2 | Experiment 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHAM | 21.52 (0.82) | 18.08 (0.49) | 17.94 (0.83) |

| Ipsilateral | 19.63 (0.65) | 20.02 (0.74) | 17.94 (0.76) |

| Contralateral | 20.35 (0.93) | 20.24 (1.03) | 18.83 (0.55) |

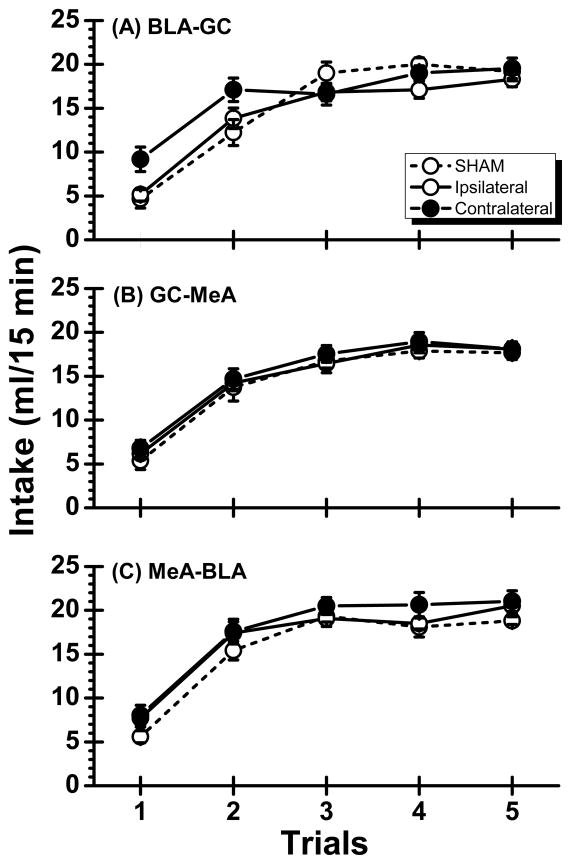

Figure 2A summarizes the saccharin intake of Experiment 1. Inspection of the figure suggests that the neurologically intact subjects and the rats with ipsilateral BLA-GC lesions consumed low amounts of saccharin on Trial 1 (i.e., taste neophobia) and gradually increased their intake of the tastant on Trials 2 and 3 (i.e., habituation of neophobia). However, the neophobic reaction was attenuated, but clearly not eliminated, in rats with contralateral BLA-GC lesions that also showed normal levels of tastant intake at asymptote. In confirmation of these observations, a two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Trial, F(4,108) = 105.05, p < 0.001, and more importantly, a significant Trial x Lesion interaction, F(8,108) = 3.56, p < 0.01; the main effect of Lesion was not significant (p > 0.20). Post hoc comparisons (simple main effects) further revealed that Group Contralateral consumed significantly more on Trials 1 and 2 than Group SHAM or Group Ipsilateral (ps < 0.05) and that all three groups reached the same asymptote on Trials 3 – 5 (ps > 0.05). This pattern of results indicates that the BLA-GC work as a functional unit in processing new taste information.

Fig. 2.

Mean (±SE) saccharin intake across the 5 taste trials for neurologically intact (SHAM) subjects and rats with either ipsilateral or contralateral lesions in Experiment 1 (BLA-GC; Panel A), Experiment 2 (GC-MeA; Panel B) and Experiment 3 (MeA-BLA; Panel C).

3.2.2. Experiment 2: GC-MeA lesions

Baseline water data (collapsed across the final 3 days) from Experiment 2 are shown in Table 1. A two-way ANOVA revealed that there was no main effect of Lesion (p > 0.10) or Day (p = 0.20) and no lesion X day interaction (F < 1). Thus, whether ipsilateral or contralateral, lesions of the GC and MeA did not affect water consumption.

The saccharin intake of Experiment 2 is summarized in Figure 2B. As shown in the figure, asymmetric GC-MeA lesions had no discernible influence on taste neophobia or on the level of tastant intake at asymptote. A Lesion × Trial ANOVA found no significant main effect of Lesion (F < 1) or Lesion × Trial interaction (F < 1). There was, however, a significant main effect of Trial, F(4,112) = 163.04, p < 0.001. Post hoc comparisons confirmed that the rats consumed significantly less on Trial 1 than on Trial 2 and less on Trial 2 than on Trial 3 (ps < 0.05). Maximal consumption of saccharin was achieved on Trial 3 and did not differ across Trials 3 – 5 (ps > 0.05). These results demonstrate that the GC and MeA work independently in modulating taste neophobia.

3.2.3. Experiment 3: MeA-BLA lesions

Table 1 shows the baseline water data collapsed over the final three days before the first neophobia trial. An ANOVA conducted on these data found no significant main effect of Lesion (F < 1) and no significant lesion X day interaction (p > 0.10). However, the main effect of Day was significant, F(2,62) = 9.56, p < 0.05. Post hoc analysis revealed that rats consumed comparable amount of water on the last two water days (p > 0.05) and that intake on each of these days was significantly higher than that on the first water baseline day (ps < 0.05). Thus, neither ipsilateral nor contralateral lesions of the MeA and BLA influenced water intake.

Saccharin consumption levels in all three groups (SHAM, Ipsilateral, and Contralateral) are depicted in Figure 2C. Inspection of the figure suggests that MeA-BLA lesions affected neither taste neophobia nor the habituation of neophobia. This view was confirmed with a two-way mixed ANOVA, which found no significant main effect of Lesion (p > 0.20) and no significant Lesion × Trial interaction (p > 0.40). There was, however, a significant main effect of Trial, F(4,124) = 245.12, p < 0.001. Post hoc comparisons indicated that intake increased from Trial 1 to Trial 2 to Trial 3 (ps < 0.05) and thereafter was constant at the same level (i.e., asymptote; ps > 0.05). The absence of a behavioral deficit in rats with asymmetric MeA-BLA lesions indicates that these two amygdala sub-nuclei do not functionally interact to modulate taste neophobia.

4. Discussion

Using asymmetric unilateral lesions, the current study examined whether the amygdala and GC function independently or interdependently during the occurrence of taste neophobia. The results revealed that rats with asymmetric BLA-GC lesions consumed more of the novel saccharin solution relative to both neurologically intact rats and animals with ipsilateral lesions of the two brain areas. That is, contralateral lesions of the BLA and GC attenuated the magnitude of the neophobic reaction. On the other hand, neither GC-MeA nor MeA-BLA asymmetric lesions had any influence on the consumption of the novel tastant. One may argue that the deficits caused by BLA-GC asymmetric lesions are due to the summation of the two sub-threshold effects from each unilateral lesion. However, this seems unlikely given the null effect of ipsilateral lesions. Overall, the obtained pattern of results suggests that the neophobic reaction to a new tastant depends, in part, upon an interaction between the BLA and GC whereas the MeA works independently of the BLA or GC. Furthermore, the impairment found in rats with BLA-GC asymmetric lesions explains why similar deficits (rather than null effects due to behavioral compensation) are found in rats with bilateral lesions of either the BLA or GC.

The view that a functional BLA-GC loop is involved in the expression of taste neophobia has relevance to the interpretation of another taste-guided deficit consequent to lesions of either structure. That is, it may explain why lesions of the BLA or GC have a similar influence on the acquisition of CTAs. CTA is a learned behavior that prevents the repeated ingestion of a toxic tastant (for reviews see [5,9,47,60]). It is, moreover, well established that the rate of CTA acquisition varies as a function of the novelty of the tastant. Specifically, CTAs are acquired more readily when a novel tastant is used rather than a familiar and safe tastant [26,61], a phenomenon termed latent inhibition [41,42]. We suggest that an intact BLA-GC loop is important for the processing of, or responsivity to, taste novelty such that disruption of the circuit causes the animal to treat the new taste as if it were less novel (i.e., as a more familiar taste). If this hypothesis is correct then lesions of components of this amygdalocortical loop should not only result in an attenuation of taste neophobia they should also produce a selective deficit in CTA acquisition. That is, because of a latent inhibition-like effect, BLA or GC lesions would be expected to delay (but not prevent) acquisition of CTA when the taste is novel and to have no influence on learning when the taste is familiar and safe. As the literature shows, this pattern of CTA performance is found in rats with bilateral lesions of the BLA (e.g., [48,67]) or with bilateral lesions of the GC (e.g., [28,63,64]). Indeed, this analysis suggests that the BLA and GC have no role in the CTA mechanism – the obtained deficits are understood as the expected consequence of a disruption in taste novelty.

The finding that asymmetric lesions of the GC-MeA and MeA-BLA produced no impairment in taste neophobia was not expected on the basis that bilateral lesions of this sub-nucleus of the amygdala attenuate taste neophobia [40]. This null result implies that the MeA has a different role in taste neophobia than the BLA and GC, even though similar behavioral deficits are found in rats with bilateral lesions of any one of these three areas. What, then, is the role of the MeA in taste neophobia? The answer to this question is not immediately clear but any interpretation will need to explain the following two facts. First, the literature shows that MeA lesions have little or no influence on CTA acquisition [1,46,62,66,74]. Second, unlike the BLA and GC, c-Fos expression is not elevated in the MeA consequent to intake of a novel tastant (0.5% saccharin [39]). Stated in this way, one may doubt whether the MeA has a role in taste neophobia per se. Indeed, an explanation for the overconsumption on first exposure to a taste stimulus (but not to an aqueous odor or an oral trigeminal stimulus [40]) might simply appeal to a lesion-induced deficit in taste detection such as, for example, a reduction in perceived taste intensity or concentration. That said, to the best of our knowledge there is no evidence that taste information reaches the MeA. The central nucleus of the amygdala is a major recipient of ascending taste afferents and the BLA also receives taste information (for reviews of the central gustatory system see [18,43,52,72]). However, whether either or both of these two sub-regions of the amygdala relays taste information to the MeA remains a matter of speculation. An alternative interpretation of MeA function focuses on the role of the area in the unconditioned response to acute stress of various types (including restraint, social interactions and novel environment [13,17,32,44]). But, this analysis runs into the immediate difficulty that it cannot explain the selective nature of the neophobia deficit (disrupting taste but sparing odor and trigeminal neophobia tested in an identical procedure). Thus, we return to the basic fact that MeA lesions attenuate taste neophobia but we have no ready explanation for this deficit.

The way forward is to better define the nature of the taste neophobia deficit in rats with BLA, GC, and MeA lesions. This leads to the realization that little is known about the processes involved in the normal occurrence of taste neophobia. We have recently approached this latter issue by asking whether neophobia influences taste palatability. Our initial attempt to investigate this question, using taste reactivity methodology, yielded null results: brief exposure to the tastant did not modify the frequency of hedonic orofacial responses across trials [51]. However, our second attempt, using an alternative methodology to assess palatability, was more successful. That is, analyzing the microstructure of lick patterns, we ([37] see also [4,38]) have recently established that the recovery from taste neophobia does, indeed, involve an increase in taste palatability. In other words, a taste is perceived as less pleasurable when it is novel than when it is familiar. If our hypothesis (that BLA and GC lesions cause rats to treat a new tastant as if it was familiar and safe) is correct then we should expect that lesions of either structure would result in elevated palatability on first encounter with a new tastant. To our knowledge, only one study [58] has provided data relevant to this issue in rats with bilateral BLA lesions. Unfortunately, that study employed taste reactivity methodology which, as noted above, is not sensitive to neophobia-induced changes in taste palatability. With regard to the MeA, because lesions of this structure do not appear to produce a latent inhibition-like delay in CTA acquisition, then the clear prediction would be that MeA lesions should have no influence on taste palatability despite the established over-consumption on first exposure to the new tastant. The direction for future research, then, is to investigate the influence of BLA, GC and MeA lesions on taste palatability to test the merits of our interpretation of the present results.

Research Highlights.

We examined whether amygdala and gustatory insular cortex connections are required for taste neophobia.

Asymmetric unilateral lesions of the BLA and GC attenuated taste neophobia.

Asymmetric unilateral lesions of the GC-MeA or MeA-BLA had no influence on taste neophobia.

We conclude that the BLA and GC operate as a unit whereas the MeA function independently in processing a novel tastant.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant DC06456 from the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Portions of the data in this article were presented at the 41st Annual Convention of the Society for Neuroscience in Washington, DC, in November 2011.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Aggleton JP, Petrides M, Iversen SD. Differential effects of amygdaloid lesions on conditioned taste aversion learning by rats. Physiol Behav. 1981;27:397–400. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(81)90322-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychological Association. Guidelines for Ethical Conduct in the Care and Use of Animals. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arakawa H, Arakawa K, Deak T. Oxytocin and vasopressin in the medial amygdala differentially modulate approach and avoidance behavior toward illness-related social odor. Neurosci. 2010;171:1141–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arthurs J, Lin J-Y, Amodeo LR, Reilly S. Reduced palatability in drug-induced taste aversion: II. Aversive and rewarding unconditioned stimuli. Behav Neurosci. 2012;126:423–432. doi: 10.1037/a0027676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barker LM, Best M, Domjan M, editors. Learning Mechanisms in Food Selection. Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnett SA. Experiments on “neophobia” in wild and laboratory rats. Brit J Psychol. 1958;49:195–201. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1958.tb00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Best MR, Barker LM. The nature of “learned safety” and its role in the delay of reinforcement gradient. In: Barker LM, Best M, Domjan M, editors. Learning Mechanisms in Food Selection. Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press; 1977. pp. 295–317. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bielavska E, Roldan G. Ipsilateral connections between the gustatory cortex, amygdala and parabrachial nucleus are necessary for acquisition and retrieval of conditioned taste aversion in rats. Behav Brain Res. 1996;81:25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(96)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braveman NS, Bronstein P, editors. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1985. Experimental assessments and clinical applications of conditioned food aversions; p. 443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brigham AJ, Sibly RM. A review of the phenomenon of neophobia. In: Cowan DP, Feare CJ, editors. Advances in Vertebrate Pest Management. Furth (Germany): Filander Verlag; 1999. pp. 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carroll ME, Dinc HI, Levy CJ, Smith JC. Demonstrations of neophobia and enhanced neophobia in the albino rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1975;89:457–467. doi: 10.1037/h0077041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corey DT. The determinants of exploration and neophobia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1978;2:235–253. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cullinan WE, Herman JP, Battaglia DF, Akil H, Watson SJ. Pattern and time course of immediate early gene expression in rat brain following acute stress. Neurosci. 1995;64:477–505. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devan BD, White NM. Parallel information processing in the dorsal striatum: Relation to hippocampal function. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2789–2798. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-07-02789.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Domjan M. Attenuation and enhancement of neophobia for edible substances. In: Barker LM, Best M, Domjan M, editors. Learning Mechanisms in Food Selection. Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press; 1977. pp. 151–179. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunn LT, Everitt BJ. Double dissociations of the effects of amygdala and insular cortex lesions on conditioned taste aversion, passive avoidance, and neophobia in the rat using the excitotoxin ibotenic acid. Behav Neurosci. 1988;102:3–23. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.102.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emmert MH, Herman JP. Differential forebrain c-fos mRNA induction by ether inhalation and novelty: evidence for distinctive stress pathways. Brain Res. 1999;845:60–67. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01931-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finger TE. Gustatory nuclei and pathways in the central nervous system. In: Finger TE, Silver WL, editors. Neurobiology of Taste and Smell. New York: Wiley; 1987. pp. 331–353. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitzgerald RE, Burton MJ. Neophobia and conditioned taste aversion deficits in the rat produced by undercutting temporal cortex. Physiol Behav. 1983;30:203–206. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(83)90006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Floresco SB, Seamans JK, Phillips AG. Selective roles for hippocampal, prefrontal cortical, and ventral striatal circuits in radial-arm maze tasks with or without delay. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1880–1890. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-05-01880.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaffan D, Harrison S. Amygdelectomy and disconnection in visual learning for auditory secondary reinforcement by monkeys. J Neurosci. 1987;7:2285–2292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gomez-Chacon B, Gamiz F, Gallo M. Basolateral amygdala lesions attenuate safe taste memory-related c-fos expression in the rat perirhinal cortex. Behav Brain Res. 2012;230:418–422. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green KF, Parker LA. Gustatory memory: Incubation and interference. Behav Biol. 1975;13:359–367. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6773(75)91416-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han JS, McMahan RW, Holland P, Gallagher M. The role of an amygdalo-nigrostriatal pathway in associative learning. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3913–3919. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03913.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalat JW. Status of “learned safety” or “learned noncorrelation” as a mechanism in taste-aversion learning. In: Barker LM, Best M, Domjan M, editors. Learning Mechanisms in Food Selection. Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press; 1977. pp. 273–293. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalat JW, Rozin P. “Learned safety” as a mechanism in long-delay taste aversion learning in rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1973;83:198–207. doi: 10.1037/h0034424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kesner RP, Berman RF, Tardif R. Place and taste aversion learning: Role of basal forebrain, parietal cortex, and amygdala. Brain Res Bull. 1992;29:345–353. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(92)90066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiefer SW, Braun JJ. Absence of differential associative responses to novel and familiar taste stimuli in rats lacking gustatory neocortex. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1977;91:498–507. doi: 10.1037/h0077347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiefer SW, Grijalva CV. Taste reactivity in rats following lesions of the zona incerta or amygdala. Behav. 1980;25:549–554. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(80)90120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kiefer SW, Rusiniak KW, Garcia J. Flavor-illness aversions: gustatory neocortex ablations disrupt taste but not taste-potentiated odor cues. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1982;96:540–548. doi: 10.1037/h0077910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolakowska L, Larue-Achagiotis C, Le Magnen J. Comparative effects of lesions of the basolateral and lateral nuclei of the amygdala on neophobia and conditioned taste aversion in rats. Physiol Behav. 1984;32:647–651. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(84)90320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kollack-Walker S, Watson SJ, Akil H. Social stress in hamsters: defeat activates specific neurocircuits within the brain. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8842–8855. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-22-08842.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kosar E, Grill HJ, Norgren R. Gustatory cortex in the rat. I. Physiological properties and cytoarchitecture. Brain Res. 1986;379:329–341. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90787-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krettek JE, Price JL. Projections from the amygdaloid complex to the cerebral cortex and thalamus in the rat and cat. J Comp Neurol. 1977;172:687–722. doi: 10.1002/cne.901720408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lasiter PS. Cortical substrates of taste aversion learning: Direct amygdalocortical projections to the gustatory neocortex do not mediate conditioned taste aversion learning. Physiol Psychol. 1982;10:377–383. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li C-I, Maglinao TL, Takahashi LK. Medial amygdala modulation of predator odor-induced unconditioned fear in the rat. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118:324–332. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin J-Y, Amodeo LR, Arthurs J, Reilly S. Taste neophobia and palatability: The pleasure of drinking. Physiol Behav. 2012;106:515–519. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin J-Y, Arthurs J, Amodeo LR, Reilly S. Reduced palatability in drug-induced taste aversion: I. Variations in the initial value of the conditioned stimulus. Behav Neurosci. 2012;126:433–444. doi: 10.1037/a0027674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin J-Y, Roman C, Arthurs J, Reilly S. Taste neophobia and c-Fos expression in the rat brain. Brain Res. 2012;1448:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin J-Y, Roman C, St Andre J, Reilly S. Taste, olfactory and trigeminal neophobia in rats with forebrain lesions. Brain Res. 2009;1251:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lubow RE. Latent Inhibition and Conditioned Attention Theory. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lubow RE. Conditioned taste aversion and latent inhibition: A review. In: Reilly S, Schachtman TR, editors. Conditioned Taste Aversion: Behavioral and Neural Processes. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 37–57. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lundy RF, Jr, Norgren R. The rat nervous system. In: Paxinos G, editor. Gustatory system. 3. San Diego: Academic Press; 2004. pp. 891–921. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martinez M, Phillips PJ, Herbert J. Adaptation in patterns of c-fos expression in the brain associated with exposure to either single or repeated social stress in male rats. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:20–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McDonald AJ. Cortical pathways to the mammalian amygdala. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;55:257–332. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meliza LL, Leung PMB, Rogers QR. Effect of anterior prepyriform and medial amygdaloid lesions on acquisition of taste-avoidance and response to dietary amino acid balance. Physiol Behav. 1981;26:1031–1035. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(81)90205-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Milgram NW, Krames L, Alloway TM, editors. Food Aversion Learning. New York: Plenum Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morris R, Frey S, Kasambira T, Petrides M. Ibotenic acid lesions of the basolateral, but not central, amygdala interfere with conditioned taste aversion: evidence from a combined behavioral and anatomical tract-tracing investigation. Behav Neurosci. 1999;113:291–302. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.113.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nachman M, Ashe JH. Effects of basolateral amygdala lesions on neophobia, learned taste aversions, and sodium appetite in rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1974;87:622–643. doi: 10.1037/h0036973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.National Institutes of Health. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neath KN, Limebeer CL, Reilly S, Parker LA. Increased liking for a solution is not necessary for the attenuation of neophobia in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2010;124:398–404. doi: 10.1037/a0019505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Norgren R. Central neural mechanisms of taste. In: Darien-Smith I, editor. Handbook of physiology: The nervous system III. Sensory processes. Bethesda, MD: American Physiological Society; 1984. pp. 1087–1128. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Olton DS. The function of septo-hippocampal connections in spatially organized behaviour. Functions of the Septo-hippocampal System; Ciba Foundation Symposium; New York: Elsevier/Excerpta; 1978. pp. 58pp. 327–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 5. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petrulis A, Johnston RE. Lesions centered on the medial amygdala impair scent-marking and sex–odor recognition but spare discrimination of individual odors in female golden hamsters. Behav Neurosci. 1999;113:345–357. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.113.2.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pitkanen A. Connectivity of the rat amygdaloid complex. In: Aggleton JP, editor. The Amygdala: A Functional Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 31–116. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Price JL. Comparative aspects of amygdala connectivity. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;985:50–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rana SA, Parker LA. Differential effects of neurotoxininduced lesions of the basolateral amygdala and central nucleus of the amygdala on lithium-induced conditioned disgust reactions and conditioned taste avoidance. Behav Brain Res. 2008;189:284–297. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reilly S, Bornovalova MA. Conditioned taste aversion and amygdala lesions in the rat: a critical review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:1067–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reilly S, Schachtman TR, editors. Conditioned Taste Aversion: Behavioral and Neural Processes. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Revusky S, Bedarf EW. Association of illness with the prior ingestion of novel foods. Science. 1967;155:219–220. doi: 10.1126/science.155.3759.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rollins BL, Stines SG, McGuire HB, King BM. Effects of amygdala lesions on body weight, conditioned taste aversion, and neophobia. Physiol Behav. 2001;72:735–742. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00433-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roman C, Lin J-Y, Reilly S. Conditioned taste aversion and latent inhibition following extensive taste preexposure in rats with insular cortex lesions. Brain Res. 2009;1259:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.12.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roman C, Reilly S. Effects of insular cortex lesions on conditioned taste aversion and latent inhibition. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:2627–2632. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rosen JB, Pagani JH, Rolla KLG, Davis C. Analysis of behavioral constraints and the neuroanatomy of fear to the predator odor trimethylthiazoline: a model for animal phobias. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:1267–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schoenfeld TA, Hamilton LW. Disruption of appetite but not hunger or satiety following small lesions in the amygdala of rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1981;95:565–587. doi: 10.1037/h0077801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shi CJ, Cassell MD. Cortical, thalamic, and amygdaloid connections of the anterior and posterior insular cortices. J Comp Neurol. 1998;399:440–468. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19981005)399:4<440::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shipley MT, McLean JH, Ennis M. The olfactory system. In: Paxinos G, editor. The Rat Nervous System. 2. San Diego: Academic Press; 1995. pp. 899–926. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sripanidkulchai K, Sripanidkulchai B, Wyss JM. The cortical projection of the basolateral amygdaloid nucleus in the rat: a retrograde fluorescent dye study. J Comp Neurol. 1984;229:419–431. doi: 10.1002/cne.902290310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.St Andre J, Reilly S. Effects of central and basolateral amygdala lesions on conditioned taste aversion and latent inhibition. Behav Neurosci. 2007;121:90–99. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Takahashi LK, Hubbard DT, Lee I, Dar Y, Sipes SM. Predator odor-induced conditioned fear involves the basolateral and medial amygdala. Behav Neurosci. 2007;121:100–110. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Travers SP. Orosensory processing in neural systems of the nucleus of the solitary tract. In: Simon SA, Roper SD, editors. Mechanisms of taste transduction. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1993. pp. 339–394. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yamamoto T, Azuma S, Kawamura Y. Functional relations between the cortical gustatory area and the amygdala: electrophysiological and behavioral studies in rats. Exp Brain Res. 1984;56:23–31. doi: 10.1007/BF00237438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yamamoto T, Fujimoto Y, Shimura T, Sakai N. Conditioned taste aversion in rats with excitotoxic brain lesions. Neurosci Res. 1995;22:31–49. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(95)00875-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]