Abstract

Here, we report on a Consultation Clinic for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) which we established at Tokushima University Hospital in July of 2007 with the aim of providing person-to-person information on CAM, though not CAM therapy itself. In December of 2008, we received 55 applications for consultation, 37% concerning health foods, 37% Japanese herbal medicine (Kampo), and 26% various other topics. The consultants (nutritionists and pharmacists) communicated individually with 38 applicants; malignancies (26%) and cardiovascular disease (24%) were the main underlying concerns. To promote the quality of consultation, data was collected by means of focus group interviews concerning the perspective of the consultants. Safe and effective use of CAM requires a network of communication linking individuals, consultation teams, physicians, primary care institutions and university hospitals. To advance this goal, we plan to broaden the efforts described herein. Our findings indicate that the specific role of the consultation clinic in promoting the scientific use of CAM merits further study.

Keywords: complementary and alternative medicine, clinic, present status, university hospital

Introduction

The use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is increasing in Japan, as in other countries. To a greater degree than other forms of CAM, traditional Japanese herbal medicine (Kampo) has achieved recognition and integration into the Japanese healthcare system. Regarding the attitudes of Japanese doctors to CAM, Imanishi et al (1) reported that 267 (73%) of the responding physicians practiced some form of CAM, and that most doctors practicing CAM (96%) were Kampo practitioners. Kampo is the form of CAM that doctors themselves use most frequently, and many medical universities and organizations offer pre- and post-graduate programs in Kampo.

Many patients, on the other hand, seek specific outcomes and use other types of CAM, particularly health foods and dietary supplements. In a study of 3100 Japanese cancer patients, Hyodo et al (2) reported that 44.6% used some type of CAM, and that 96.2% of the uses were health foods including dietary supplements. In a survey of patients attending general outpatient clinics in Tokyo, Hori et al (3) reported that 50% of the 496 patients who responded were using or had used at least one CAM therapy within the previous 12 months. These patients most often used massage (43%), vitamins (35%) and health foods including dietary supplements (23%). Nevertheless, many Japanese physicians assign a limited role to CAM practices other than Kampo. Unfortunately, patients have limited access to scientific information concerning CAM, and only a few public university hospitals in Japan (e.g., Osaka University since 2002 and Kanazawa University since 2008) have a CAM clinic.

At Tokushima University Hospital, an academic hospital in Tokushima, Shikoku, we established a CAM consultation clinic in July of 2007 to provide reliable information on CAM directed to the specific needs of each applicant. Here, we report on the current activities of the CAM clinic.

Methods

CAM clinics at Tokushima University Hospital and other academic hospitals in Japan

According to our protocol, a nutritionist first accepts each application, and schedules an appointment with a suitable consultant. Application is not limited to patients treated at the Tokushima University Hospital. Each consultant provides information on the CAM topic relevant to the applicant’s query. No actual CAM treatment is provided; however, when appropriate, the patient is referred to clinical CAM trials (limited to health food trials at present) ongoing at the Tokushima University Hospital. The current consultants include two nutritionists and four pharmacists who are professors and associate professors at the University of Tokushima Graduate School, and two pharmacists employed by Tokushima University Hospital. We deal primarily with health foods, including dietary supplements and Kampo, and do not accept consultations for other types of CAM, such as acupuncture, Ayurveda, mind-body interventions or energy therapies. Currently, we do not charge a consulting fee. Although many hospitals in Japan, including public university hospitals, have clinics for Kampo consultation and treatment, only a few of these hospitals (Osaka University since 2002, and Kanazawa University since 2008) have CAM clinics.

Analysis of consultations and quality issues to be resolved at CAM clinics

To evaluate the quality of the CAM consultation at our clinic, data was collected in focus group interviews concerning the perspective of the consultants. All consultants contributed equally as investigators in this study. The director of the CAM clinic facilitated several group interviews in 2008. To avoid facilitator dependency and to respect the group dynamics, the facilitator introduced the major topics only briefly, without elaboration. The topics included i) how to communicate with physicians and collect information on the treatment itself, and ii) selection of the appropriate information source to answer each patient question. After recording the general remarks, group members were encouraged to express their views on how best to provide scientific information regarding CAM. In the subsequent discussion, possible measures were suggested. The data presented here include representative quotations and samples of dialogue between participants.

Results

Characteristics of the applicants

Of the 55 applicants, 6 requested treatment beyond what was offered at the clinic. In most cases, this was for a specific CAM; e.g., a health food for a chronic disease. Of the other 49 applicants, 11 requested general advice concerning CAM, and the first-contact nutritionist addressed their needs. The other 38 applicants worked individually with the consultants. Of the 55 applicants, 20 (37%) sought information on health foods including dietary supplements; 20 (37%) requested information on Kampo, and 15 (26%) sought advice on various other issues.

Characteristics of the consultations

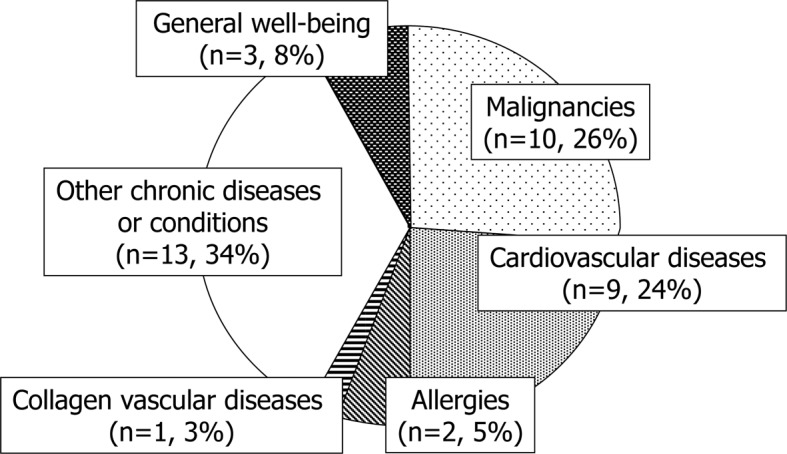

Of the 38 applicants who met with the consultants, 46% (n=18) were male and 54% (n=20) were female, with ages ranging from 34 to 83 years of age (30–39 years of age, n=5; 40–49, n=5; 50–59, n=4; 60–69, n=6; 70–79, n=11; 80–89, n=4; and undisclosed, n=3). Eighty-one percent (n=31) of these applicants were patients at medical institutions [Tokushima University Hospital, 25% (n=10); other medical institutions, 45% (n=17); or both, 11% (n=4)]. The principal concerns of these 38 individuals included malignancies (n=10, 26%), cardiovascular disease (n=9, 24%), allergies (n=2, 5%), collagen vascular diseases (n=1, 3%), other chronic diseases or conditions (n=13, 34%) and general well-being (n=3, 8%) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The health status or underlying disease of 38 patients who received consultation at the Consultation Clinic for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Tokushima University Hospital, between July 2007 and December 2008.

Quality issues to be resolved at the CAM clinic

Communication with physicians, including the acquisituin of information regarding prior/current treatment. In general, the consultants reported that most applicants had not discussed the use of CAM or their desire to use CAM with their personal physicians. One patient presented with a history of warfarin treatment. The consultant handling the case advised the patient regarding the use of certain health foods that may adversely interact with warfarin. However, he did not contact the patient’s physician directly to obtain information regarding the warfarin treatment; rather, he inferred the use of warfarin from a drug diary provided by the patient’s pharmacist. Another case concerned a patient taking supplemental iron in conjunction with iron-chelation therapy for liver disease. All of the consultants agreed that the the use of CAM by the applicants urgently needed to be assessed, and that this ought to be communicated to their physician(s). Although the drug diary proved useful here, a system or tool with universal access must be established to promote communication between physicians and CAM consultants. In addition, one consultant mentioned the need to better inform physicians as well as assisting medical personnel and patients regarding the activities of the CAM clinic.

Information sources for individual consultations. Evidence from clinical trials provided the basis for most answers given by the consultants to the patients regarding CAM. Therefore, consultants should be alert to recent publications on the subject of CAM, so as to best address each applicant’s concern. However, one consultant expressed concern at the difficulties in keeping abreast of the literature. By contrast, since information on the effects of health foods in humans is limited, another consultant expressed the opposite concern, having had to tell an applicant that “there is no positive scientific evidence regarding the health food you are interested in”. All agreed with a consultant who emphasized the need to provide information to patients on the possible adverse effects of CAM, used alone or in conjunction with standard treatments. Additionally, all consultants emphasized the need for clinical trials to establish the validity of CAM practices. It should also be noted that applicants often appealed to consultants to recommend a specific form of CAM, which could not credibly be done at our clinic.

Discussion

At the CAM clinic of the Tokushima University Hospital, we assumed the challenge to provide person-to-person, scientifically based information on CAM to regional consumers. Most of the 55 applicants to our clinic described herein expressed interest in health foods, including dietary supplements and Kampo practices. In a Japanese telephone survey with 1000 respondents, Yamashita et al (4) reported that 76.0% of those interviewed had used at least one CAM therapy in the past 12 months, and that the therapies primarily included nutritional and tonic drinks, dietary supplements, health-related appliances and herbs, and over-the-counter Kampo remedies. We began our services with consultation involving health foods, including dietary supplements and Kampo. This strategy meets our present needs, but we plan to extend our activities to other areas of CAM in the future.

As CAM use increases in Japan, Japanese physicians may feel pressed when patients ask them for advice on CAM, since there is little evidence regarding the efficacy or side effects of specific treatments, and no reliable guidelines are available to help them integrate CAM into conventional therapy (5). In a nationwide survey of cancer patients (2), 60.7% of those who used CAM products did so without consulting a doctor. As well as providing scientific information about CAM to applicants, we hope to establish channels of communication between physicians, patients and CAM practitioners (6,7). The main reasons patients provided for not disclosing their use of CAM to their physicians included concerns about a negative response from practitioners, the belief that the practitioner did not need to know about their CAM use, and the fact that the practitioner did not ask (8). If physicians increase their knowledge concerning CAM, they will find such conversations with patients less daunting. Shelly et al (9) suggested a different approach. They believe that clinicians must initiate the discussion, though they do not need to be experts in CAM to do so. They must simply show non-judgmental interest and candidly admit their limited knowledge of CAM. We plan to suggest this approach to physicians, with the applicants permission.

Consumers often use CAM on their own initiative, with little scientific knowledge. In a nationwide survey of cancer patients (2), 57.3% of those who used CAM products lacked the knowledge to do so safely and effectively. To partially address this issue, scientific leaflets or books are valuable. For example, a study group funded by a grant from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan and supervised by Dr Yoshimitsu Sumiyoshi of the National Shikoku Cancer Center published a patient-oriented guidebook for CAM in cancer therapy (first edition in 2006 and the second in 2008) [http://www.shikoku-cc.go.jp/kranke/cam/dl/index.html#DL02 (in Japanese)]. Reports of the adverse effects of some CAM remedies (10,11) highlight the need for an up-to-date knowledge of CAM development and application.

Recently, several societies and institutions in Japan have established courses of study in CAM for physicians, pharmacists, nutritionists and other specialists, leading to a degree and/or certified authorization to practice as a CAM specialist or advisor. The Japanese Society for Complementary and Alternative Medicine authorizes a CAM Scholarship for Physicians and Dentists. The National Institute of Health and Nutrition authorizes Nutrition Representatives. Two public university hospitals, Osaka University (since 2002) and Kanazawa University (since 2008) have CAM clinics in operation. As these clinics develop their services, it is important that they share their methodologies and evaluations of outcome. To foster this process, we held the First Meeting for Staffs of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Clinics of University Hospitals in July of 2008 (12), and plan to continue these conferences for university hospitals committed to this cause. In addition, we will work to inform physicians, other health care personnel and patients regarding the capacities of CAM clinics. The comprehensive role of the consultation clinic in the promotion of evidence-based CAM merits further study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Yoshimitsu Sumiyoshi of the National Shikoku Cancer Center Hospital for the valuable comments. We also thank Toshiko Miyamoto, Shigemi Takai, Akiyo Akaishi, Hiromi Inoue, Akiko Kume, Tomoko Saijo, Soichiro Tajima, Makiko Yamagami, Noriko Urakawa, Tomoko Shimomura, Junichiro Imoto and Akane Suzuki of the Clinical Trial Center for Developmental Therapeutics, Tokushima University Hospital for the encouragement and support.

References

- 1.Imanishi J, Watanabe S, Satoh M, Ozasa K. Japanese doctors’ attitudes to complementary medicine. Lancet. 1999;354:1735–1736. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)76729-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hyodo I, Amano N, Eguchi K, et al. Nationwide survey on complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients in Japan. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2645–2654. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hori S, Mihaylov I, Vasconcelos JC, McCoubrie M. Patterns of complementary and alternative medicine use amongst outpatients in Tokyo, Japan. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki N. Complementary and alternative medicine: a Japanese perspective. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2004;1:113–118. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamashita H, Tsukayama H, Sugishita C. Popularity of complementary and alternative medicine in Japan: a telephone survey. Complement Ther Med. 2002;10:84–93. doi: 10.1054/ctim.2002.0519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sirois FM. Motivations for consulting complementary and alternative medicine practitioners: a comparison of consumers from 1997-8 and 2005. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ben-Arye E, Frenkel M, Klein A, Scharf M. Attitudes toward integration of complementary and alternative medicine in primary care: perspectives of patients, physicians and complementary practitioners. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson A, McGrail MR. Disclosure of CAM use to medical practitioners: a review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Complement Ther Med. 2004;12:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shelley BM, Sussman AL, Williams RL, Segal AR, Crabtree BF, on behalf of the RIOS Net Clinicians ‘They don’t ask me so I don’t tell them’: patient-clinician communication about traditional, complementary, and alternative medicine. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:139–147. doi: 10.1370/afm.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giveon MG, Liberman N, Klang S, Kahan E. Are people who use natural drugs aware of their potentially harmful side effects and reporting to family physician? Patient Educ Couns. 2004;53:5–11. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ernst E. ‘First, do not harm’ with complementary and alternative medicine. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:48–50. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yanagawa H. The First Meeting for Staffs of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Clinics of University Hospitals (in Japanese, English abstract) Jpn J Complement Altern Med. 2008;5:247–250. [Google Scholar]