Abstract

Here, we present a case of post-operative liver metastases from pancreatic head cancer in a patient with leukocytopenia, who was safely treated by hepatic arterial infusion (HAI) chemotherapy consisting of gemcitabine and 5-FU. The patient was a 61-year-old woman who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic head cancer, but was found to be an unsuitable candidate for adjuvant systemic chemotherapy due to the presence of leukocytopenia. Five months after surgery, a follow-up CT revealed two liver metastases. Intravenous systemic chemotherapy was also contraindicated due to the leukocytopenia. In the apparent absence of recurrence, excepting the liver metastases, we decided to administer HAI chemotherapy, which had already been administered following the curative surgery. HAI chemotherapy has been shown to be associated with a lower incidence of systemic side effects. Gemcitabine at a dose of 400 mg was administered via a bedside pump and infused over 30 min. After gemcitabine infusion, 250 mg of 5-FU was infused continuously over 24 h from days 1 to 5. This comprised 1 cycle of therapy. The treatment cycles were continued biweekly. After 10 cycles without severe side effects, it was found that though the size of the metastatic tumors was not reduced, tumor vascularity was. However, after the 13th treatment cycle, local recurrence and lymph node metastases were detected. By this time, the patient had recovered from the leukocytopenia, and could thus be administered systemic chemotherapy. In conclusion, HAI chemotherapy is useful and safe for the treatment of malignancies confined to the liver, even in cases where the patient is in a reduced physical condition.

Keywords: pancreatic cancer, liver metastases, hepatic arterial infusion, chemotherapy, gemcitabine, leukocytopenia

Introduction

Pancreatic carcinoma causes more than 20,000 deaths every year in Japan, with an overall 5-year survival rate of less than 5% (1,2). For patients with localized disease, radical surgery may afford long-term benefits. However, even in patients who undergo resection, the reported 5-year survival rate remains in the range of 7–24%, and in most series the median survival is only approximately 1 year, indicating that surgery alone is usually inadequate. Even after curative resection, patients with pancreatic cancer face a 50–80% local recurrence rate and a 25–50% chance of developing distant metastases (3).

Gemcitabine, a deoxycytidine analogue that competes for incorporation into DNA, thereby inhibiting its synthesis, is the key drug for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Compared to resection alone, adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine improves, although to a limited degree, survival in patients with resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma (4). However, a major drawback of adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer is the impossibility of administering the designated therapy to 20–30% of patients as a result of post-operative complications, delayed surgical recovery or early disease recurrence (5,6).

Hepatic arterial infusion (HAI) of chemotherapeutic agents is a treatment option for patients with primary or metastatic hepatic malignancies confined to the liver. The use of HAI chemotherapy is based on sound physiology and pharmacology. First, liver metastases that grow beyond 2–3 mm depend on the hepatic artery for vascularization, whereas normal liver tissues are perfused by the portal vein (7,8). Second, HAI therapy allows drug delivery to hepatic metastases not achievable by systemic administration, especially drugs with a high systemic clearance (9). Third, first-pass hepatic extraction of certain drugs results in lower systemic concentrations, and hence less systemic toxicities (10). Phase I studies of HAI chemotherapy with gemcitabine in patients with liver malignancies were recently reported (11–13).

Herein, we report a case of a patient with pancreatic head cancer and post-operative liver metastases, determined to be an unsuitable candidate for systemic chemotherapy due to leukocytopenia. The patient was treated safely by HAI consisting of gemcitabine and 5-FU.

Case report

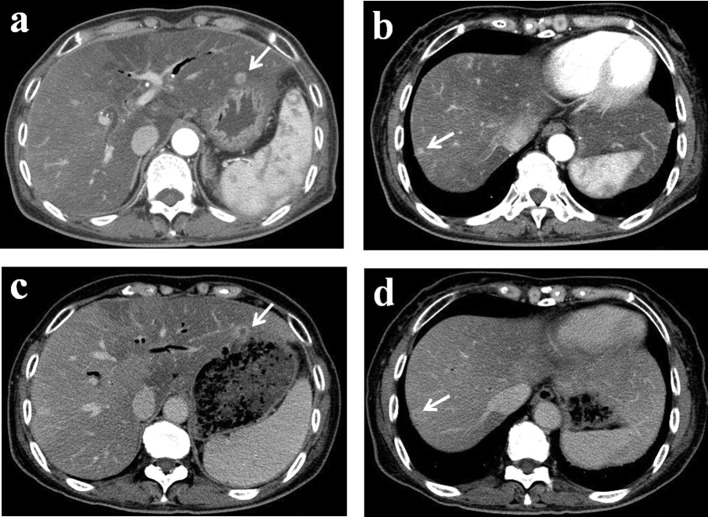

In May 2008, a 61-year-old woman underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic head cancer. Pathological examination revealed invasive ductal carcinoma of the pancreas head with three metastatic regional lymph nodes. Tumor stage was found to be T1,-N1b,-M0, stage III according to the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) classification. The patient received pre-operative chemotherapy with gemcitabine and oral S-1. Although two cycles of chemotherapy were originally planned, the second cycle was not administered because the patient developed leukocytopenia. The leukocyte count returned to within the normal range pre-operatively, and the post-operative course was uneventful. However, adjuvant systemic chemotherapy could not be administered as the patient again developed leukocytopenia (Fig. 1). Five months after surgery, a follow-up computed tomography (CT) scan revealed two liver metastases (Fig. 2a and b). Due to the leukocytopenia, intravenous systemic chemotherapy was contraindicated. In the apparent absence of recurrence, excepting the liver metastases, we decided to administer HAI chemotherapy, which had already been administered following the curative surgery and has been shown to be associated with a lower incidence of systemic side effects. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient, and the treatment was undertaken with the approval of the Medical Ethics Committee of Kanazawa University Hospital.

Figure 1.

Clinical course and changes in white blood cell (WBC) count. At the time of presentation of liver metastases, systemic chemotherapy could not be administered due to the patient’s leukocytopenia. After 13 cycles of the treatment, the HAI catheter and subcutaneous implantable port system were removed due to tube trouble. However, by this time the patient had recovered from the leukocytopenia and was treated with systemic chemotherapy.

Figure 2.

Abdominal computed tomography (CT). Two regions of liver metastases were detected in a follow up CT 5 months after surgery (a and b, arrows). After 10 cycles of HAI chemotherapy, the vascularity of the tumors was reduced (c and d, arrows).

An intrahepatic arterial catheter was percutaneously implanted after hepatic arteriography performed by right femoral puncture. The catheter was then connected to a subcutaneous implantable port system, located in the lower right abdominal area. Gemcitabine (400 mg) was dissolved in 50 ml of saline for administration by bedside pump over 30 min. After gemcitabine infusion, 250 mg of 5-FU dissolved in 50 ml of saline was infused continuously over 24 h from days 1 to 5. This comprised 1 cycle of therapy. Each treatment cycle was continued biweekly from hospital days 1 to 6.

After 10 cycles, a follow-up contrast-enhanced CT revealed no decrease in the size of the metastatic tumors [stable disease according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) guidelines]; however, tumor vascularity was reduced (Fig. 2c and d). HAI treatment was continued up to the 13th cycle without any severe side effects. However, after the 10th treatment cycle (5 months from the start of HAI chemotherapy), local recurrence was detected. Moreover, due to partial thrombosis of the hepatic artery, it was necessary to remove the HAI catheter and subcutaneous implantable port system after the 13th cycle. At this time, the leukocyte count had returned to within the normal range, and the patient was administered systemic chemotherapy (Fig. 1). Systemic chemotherapy was continued at an outpatient clinic for 22 months after the institution of HAI treatment.

Discussion

Pancreatic cancer is a fatal disease, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 5%. Surgery remains the only curative option. Therefore, in order to improve the prognosis for patients with carcinoma of the pancreatic head, we usually perform radical pancreatic resection, including wide lymph node dissection and complete removal of the extra pancreatic nerve plexus of the superior mesenteric artery or celiac axis (14–16). Compared to resection alone, adjuvant chemotherapy improves, although to a limited degree, survival in patients with resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma (4). However, a major drawback of adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer is the impossibility of administering the designated therapy to 20–30% of patients as a result of post-operative complications, delayed surgical recovery or early disease recurrence (5,6). Theoretically, these issues may be addressed by the use of neoadjuvant therapy, in order to ensure that more patients are able to receive potentially beneficial adjuvant treatment. Recently, several clinical studies of neoadjuvant chemo-(radio)-therapy in pancreatic cancer have been reported (20–24). In this case, we attempted two pre-operative cycles of chemotherapy with gemcitabine and oral S-1. However, only 1 cycle of chemotherapy was administered due to the development of leukocytopenia.

HAI chemotherapy has been studied most extensively in patients with liver metastases from colorectal cancer treated using fluorodeoxyuridine or 5-FU. Despite the significantly higher response rates to HAI than to intravenous infusion, most of these studies did not report a significant prolongation of survival; nonetheless, meta-analyses were performed (25,26). Arterial infusion chemotherapy with gemcitabine and 5-FU has previously been reported for locally advanced pancreatic cancer and liver metastases from pancreatic cancer (10,27,28). Moreover, in certain Phase I studies, HAI chemotherapy with gemcitabine was well tolerated when administered at doses of up to 1,000 mg/m2 infused over 400 min (8,9). Super-selective HAI delivers high doses of chemotherapeutic agents into the tumor vessels, producing increased regional levels with greater effectiveness and a lower incidence/severity of systemic side effects. Thus, as in the presented case, HAI chemotherapy may be indicated for liver-directed treatment.

According to the pharmacokinetics of gemcitabine, when 1,000 mg/m2 of gemcitabine is injected by intravenous infusion over 30 min, the average maximum plasma concentrations is 21,865±4,165 ng/ml by 15 min. It is reported that the flow volume of the proper hepatic artery is approximately 330 ml/ min (25). When 400 mg of gemcitabine is infused into the proper hepatic artery over 30 min, the local plasma concentration in the liver is approximately 40,000 ng/ml by 30 min. On the other hand, the plasma concentration of 250 mg of 5-FU infused into the proper hepatic artery over 24 h has been shown to be 0.5 μg/ml. This concentration is equal to the concentration obtained following administration of 30 mg/kg (1,350 mg for this patient) of 5-FU over 24 h (26). Vogl et al reported that the maximum tolerated dose of hepatic intraarterial chemotherapy with gemcitabine was 1,400 mg/m2 (8). Maruyama et al reported that when 1,000–1,500 mg of 5-FU was infused into the hepatic artery over 5 h, the maximum plasma concentration was 0.48 μg/ml, on average, and no grade 3 adverse effects were noted. In this case, gemcitabine was infused at 400 mg due to the presense of leukocytopenia (27).

At the time of presentation of liver metastases, systemic chemotherapy could not be administered to our patient due to the presence of leukocytopenia. After the 13th treatment cycle, the HAI catheter and subcutaneous implantable port system were removed due totube trouble. However, the leukocyte count had been restored to normal range by this time, and the patient was administered systemic chemotherapy.

In conclusion, HAI chemotherapy is useful and safe for the treatment of malignant tumors confined to the liver, even in patients in a poor general condition. A Phase I study of HAI chemotherapy with gemcitabine and 5-FU is underway in patients with pancreatic cancer with post-operative metastases confined to the liver.

References

- 1.Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare The Dynamic Statistics of the Population in 2005. http//www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/jinkou/kakutei05/hyo7/html.

- 2.Ishii H, Furuse J, Boku N, et al. Phase II study of gemcitabine chemotherapy alone for locally advanced pancreatic carcinoma: JCOG0506. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:573–579. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans DB, Abbruzzese JL, Willett CG. Cancer of the pancreas. In: De Vita VT Jr, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer: Priciples and Practice of Oncology. 6th edition. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2001. pp. 1126–1161. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs. observation in patients undergo curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297:267–277. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aloia TE, Lee JE, Vauthey JN, et al. Delayed recovery after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a major factor impairing the delivery of adjuvant chemotherapy? J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:347–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandy H, Bruckner H, Cooperman A, et al. Survival advantage of combined chemoradiotherapy compared with resection as the initial treatment of patients with regional pancreatic carcinoma. An outcomes trial. Cancer. 2000;89:314–327. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000715)89:2<314::aid-cncr16>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ensminger WD, Rosowsky A, Raso V. A clinical pharmacological evaluation of hepatic arterial infusions of 5-fluoro-2-deoxyuridine and 5-fluoroufacil. Cancer Res. 1978;38:3789–3792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vogl TJ, Schwarz W, Eichler K, et al. Hepatic intraarterial chemotherapy with gemcitabine in patients with unresectable cholangiocarcinoma and liver metastases of pancreatic cancer: a clinical study on maximum tolerable dose and treatment efficacy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2006;132:745–755. doi: 10.1007/s00432-006-0138-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tse AN, Wu N, Patel D, et al. A phase I study of gemcitabine given via intrahepatic pump for primary or metastatic hepatic malignancies. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;64:935–944. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-0945-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Riel JM, Peters GJ, Mammatas LH, et al. A phase I and pharmacokinetic study of gemcitabine given by 24-h hepatic arterial infusion. Euro J Cancer. 2009;45:2519–2527. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagakawa T, Nagamori M, Futakami F, et al. Result of extensive surgery for pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer. 1996;77:640–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noto M, Miwa K, Kitagawa H, et al. Pancreas head carcinoma. Frequency of invasion to soft tissue adherent to the superior mesenteric artery. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1056–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Traverso LW. Pancreatic cancer: surgery alone is not sufficient. Surg Endosc. 2006;20(Suppl 2):446–449. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-0052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spitz FR, Abbruzzese JL, Lee JE, et al. Preoperative and postoperative chemoradiation strategies in patients treated with pancreaticoduodenectomy for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:928–937. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffman JP, Lipsitz S, Pisansky T, et al. Phase II trial of preoperative radiation therapy and chemotherapy for patients with localized, resectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:317–323. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palmer DH, Stocken DD, Hewitt H, et al. A randomized phase 2 trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in resectable pancreatic cancer: gemicitabine alone versus gemcitabine combined with cisplatin. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2088–2096. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9384-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golcher H, Brunner T, Grabenbauer G, et al. Preoperative chemoradiation in adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. A single centre experience advocating a new treatment strategy. EJSO. 2008;34:756–764. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turrini O, Viret F, Zabotto LM, et al. Neoadjuvant 5 fluorouracilcisplatin chemoradiation effect on survival in patients with resectable pancreatic head adenocarcinoma: a ten-year single institution experience. Oncology. 2009;76:413–419. doi: 10.1159/000215928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takai S, Satoi S, Yanagimoto H, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation in patients with potentially resectable pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2008;36:26–32. doi: 10.1097/mpa.0b013e31814b229a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Satoi S, Yanaagimoto H, Toyokawa H, et al. Surgical results after prepoerative chemoradiation therapy for patienes with pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2009;38:282–288. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31819438c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen AD, Kemeny NE. An update on hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy for colorectal cancer. Oncologist. 2003;8:553–566. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.8-6-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mocellin S, Pilati P, Lise M, et al. Meta-analysis of hepatic arterial infusion for unresectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer: the end of an era? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5649–5654. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Homma H, Akiyama T, Mezawa S, et al. Advanced pancreatic carcinoma showing a complete response to arterial infusion chemotherapy. Int J Clin Oncol. 2004;9:197–201. doi: 10.1007/s10147-004-0388-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyanishi K, Ishiwatari H, Hayashi T. A phase I trial lf arterial infusion chemotherapy with gemcitabine and 5-fluorouracil for unresectable advanced pancreatic cancer after vascular supply distribution via superselective embolization. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38:268–274. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyn015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mogami K, Ichihara T, Sato T, et al. A case of the papilla lf vater accompanied witn a stricture of the celiac artery by the median arcuate ligament. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2008;41:1588–1593. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kikuchi K, Kanno H. Comparison for blood levels and clinical effects between tablet and other dosage forms of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) Gan To Kagaku Ryouho. 1979;6:559–565. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maruyama S, Ando M, Watayo T. Concentration of 5-FU after hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy for liver metastases of colorectal cancer. Gan To Kagaku Ryouho. 2003;30:1635–1638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]