Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to evaluate the bilirubin albumin (B/A) ratio in comparison with total serum bilirubin (TSB) for predicting acute bilirubin-induced neurologic dysfunction (BIND).

Methods

Fifty two term and near term neonates requiring phototherapy and exchange transfusion for severe hyperbilirubinemia in Children's Medical Center, Tehran, Iran, during September 2007 to September 2008, were evaluated. Serum albumin and bilirubin were measured at admission. All neonates were evaluated for acute BIND based on clinical findings.

Findings

Acute BIND developed in 5 (3.8%) neonates. B/A ratio in patients with BIND was significantly higher than in patients without BIND (P<0.001). Receiver operation characteristics (ROC) analysis identified a TSB cut off value of 25 mg/dL [area under the curve (AUC) 0.945] with a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 85%. Also, according to the ROC curve, B/A ratio cut off value for predicting acute BIND was 8 (bil mg/al g) (AUC 0.957) with sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 94%.

Conclusion

Based on our results, we suggest using B/A ratio in conjunction with TSB. This can improve the specificity and prevent unnecessary invasive therapy such as exchange transfusion in icteric neonates.

Keywords: Neonatal Jaundice, Albumins, Neurologic Dysfunction, Hyperbilirubinemia, Neonates

Introduction

Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia is a common problem in neonates; it occurs in more than 60% of late preterm and term neonates, peaking at 3–5 days of life and usually resolving by 2 weeks of age[1, 2]. Pathologic neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, defined as total serum bilirubin (TSB) concentrations >12.9 mg/dL, has been estimated to occur in up to 10% of newborns[3, 4]. In this case, unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia is potentially harmful for the central nervous system and may cause severe and permanent neurological sequelae that it defined as bilirubin induced neurological dysfunction (BIND)[5].

BIND can be divided into characteristic signs and symptoms that appear in the early stages (acute) and those that evolve over a prolonged period (chronic). The pathogenesis of BIND is multifactorial and includes interaction between the level of unconjugated bilirubin, free bilirubin, bilirubin bound to albumin, bilirubin passed through brain blood barrier and nerves damage[6]. In addition, some conditions including familial history of neonatal jaundice, blood group incompatibility, early discharge of infant from maternity, hemolysis, glucose-6-phosphat dehydroganase deficiency, sepsis, urinary tract infection, hypothyroidism, metabolic disease, breast feeding, petechiae, cephalhematoma, Asian race, and maternal age above 25 years increase the risk of neurotoxicity of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia[7–10].

Although 99.9% of unconjugated bilirubin in the circulation is bound to albumin, a relatively small fraction (only less than 0.1%) remains unbound (free bilirubin) and it can go into the brain across an intact blood brain barrier (BBB). According to the experimental studies, the concentration of free bilirubin is believed to dictate the biologic effects of bilirubin in jaundiced newborns, including its neuro-toxicity[11–13]. Improving ability to predict bilirubin neurotoxicity requires recognizing the limitations of measuring free bilirubin. At present, there are no commercial assays available for free bilirubin or albumin binding reserve in the world.

Nowadays, total serum bilirubin (TSB) is an important criterion for making decision for phototherapy and exchange transfusion in icteric neonates[10, 14].

Measurements of albumin concentration and bilirubin/albumin (B/A) ratio may provide much more insight into the likelihood of BIND. The B/A ratio is considered a surrogate parameter for free bilirubin and an interesting additional parameter in the management of hyperbilirubin-emia[15, 16].

There is little data in the literature taking B/A ratio for decision making in treatment of the neonate with severe hyperbilirubinaemia. In this study, we compared B/A ratio with TSB and chance of developing acute BIND.

Subjects and Methods

Fifty two term and near term newborn infants (up to 28 days of life) requiring phototherapy and exchange transfusion for severe hyperbilirubinemia in Children's Medical Centre, Tehran, Iran, during September 2007 to September 2008, were studied. Inclusion criteria were admission in neonatal ward and severe hyperbilirubinemia (serum bilirubin more than 18 mg/dL). Hydrops fetalis, congenital nephritic syndrome, and other diseases that mimic BIND as well as death due to other reasons were excluded.

The bilirubin level for phototherapy and exchange transfusion was defined in individual studies[10]. All neonates were followed and examined clinically for acute BIND until discharge by a pediatrician.

Acute BIND was clinically defined as a neurological deficit including decreased alertness, hypotonia, poor feeding, seizure, hypertonia of the extensor muscles, retrocollis (backward arching of the neck), and opisthotonus (backward arching of the back). Blood samples were collected at admission and immediately sent to laboratory to measure the TSB and serum albumin and calculate B/A ratio. The neonates' demographic and clinical variables were recorded.

Analysis was performed using SPSS 17.5. Independent t-test, chi square and Receiver operation characteristics (ROC) curve analysis were used. P-value <0.05 indicated statistical significance. The ethics committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences approved the protocol.

Findings

Acute BIND developed in 5 (3.8%) neonates. Table 1 shows comparison of clinical variables between neonates with BIND and other neonates discharged without any neurological deficit. There is no significant association between acute BIND and weight, age of admission, blood group or Rh incompatibility, and type of delivery (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory characteristics of the study population

| BIND (−) (n=47) | BIND (+) (n=5) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of admission (day) (mean ±SD) | 6.6±3.8 | 7.1±2.2 | 0.8 | |

| Kind of delivery (%) | Normal Vaginal | 18 (38.3) | 3 (60) | |

| Cesarean | 29 (66.7) | 2 (40) | 0.4 | |

| Near term (%) | 8 (17) | 3 (60) | ||

| Weight (gram) (mean ±SD) | Birth weight | 3152±439 | 2960±610 | 0.05 |

| Admission weight | 2972±750 | 2706±618 | ||

| Blood group incompatibility (%) | ABO | 26 (55.3) | 1 (20) | 0.2 |

| Rh | 4 (8.5) | - | 0.9 | |

| Asphyxia | − | 1 | ||

| Blood Culture (+) No. | 1 | − | ||

| Urine Culture (+) No. | 3 | − | ||

| Bilirubin mg/dl (mean ±SD) | 21.4±4.1 | 31.2±6.6 | 0.001 | |

| Albumin g/dl (mean ±SD) | 3.7±0.6 | 3.1±0.2 | 0.04 | |

| Bil/Alb ratio (mean ±SD) | 6.1±2.4 | 10±1.6 | <0.001 | |

BIND: bilirubin induced neurological dysfunction/ Bil: Bilirobin / Alb: Albomin

From 5 neonates with BIND, 3 were born near term (one of them had birth asphyxia). Mean bilirubin level of BIND neonates was significantly higher and albumin level was lower than that of neonates without BIND (P<0.001 and P=0.04, respectively) (Table 1). Also, the B/A ratio in patients with BIND was significantly higher than in patients without BIND (P<0.001).

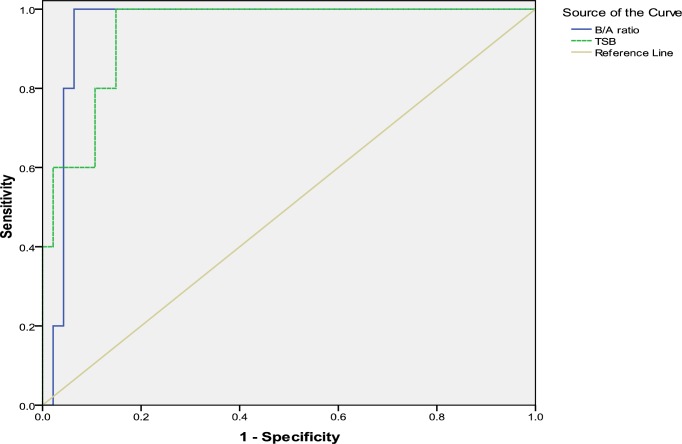

ROC analysis identified a TSB cut off value of 25 mg/dL [area under the curve (AUC) 0.945] with a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 85%. Also, according to the ROC curve, B/A ratio cut off value for predicting acute BIND was 8 mg/g (AUC 0.957) with a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 94% (Fig. 1). Statistically there was no difference between neonates with acute BIND and other neonates.

Fig. 1.

ROC curve for concentration of TSB and B/A ratio for predicting acute BIND

Discussion

In this study we compared accuracy of TSB with B/A ratio for detecting acute BIND in neonates with severe hyperbilirubinemia. Our finding showed that TSB and B/A ratio were significantly higher in patients with acute BIND than in others. The level of TSB and B/A ratio in our neonates with acute BIND were over 25 mg/dL and 8 mg/g respectively at admission. Based on the ROC curve, cutoff values of 25 mg/dL for TSB and 8 mg/g for B/A ratio were found for predicting acute BIND.

The basis of management of hyperbilirubinemia is prevention of neurotoxicity. In 2004, American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) conceded that there was no enough evidence to recommend a certain indication for photo-therapy and exchange transfusion[10]. However, indications for phototherapy and exchange transfusion in neonatal hyperbilirubinemia are based on clinical expertise and observing reduced incidences of BIND after treatment. Nowadays, the TSB is an important criterion of making decision for phototherapy and exchange transfusion in icteric neonates[14]. However, existing evidence has showed that TSB, beyond a threshold value of 20 mg/dL, is a poor discriminator of individual risk for BIND[6].

Studies showed that free bilirubin, and not TSB, is the principal determinant of bilirubin neurotoxicity[6, 13, 15]. Therefore, it seems that free bilirubin can be used as a better indicator for therapeutic purposes to decrease BIND incidence. There is presently no method available for measuring free bilirubin concentrations accurately in plasma or serum. Adjunct measurements such as albumin concentration and B/A ratio may provide more insight into the likelihood of bilirubin-induced encephalopathy[14, 16]. The B/A ratio is considered as a surrogate parameter for free bilirubin and an additional parameter in the management of hyperbilirubinemia.

Amin et al examined the usefulness of B/A ratio and free bilirubin (Bf) compared with TSB in predicting acute BIND in preterm neonates[17]. They showed that B/A ratio was significantly higher in the neonates with abnormal auditory brainstem responses (ABR) maturation. These finding was confirmed by Govaert et al[18].

Conversely, there are some published studies not showing a significant relation between B/A ratio and acute or chronic BIND[19, 20]. It seems that value of B/A ratio may be limited because many factors influence the intrinsic albumin–bilirubin binding constant in which it may be decreased by drugs (e.g. ceftriaxone) or by plasma constituents (e.g. free fatty acids) that interfere with albumin–bilirubin binding[16, 21, 22].

Although our finding showed that B/A ratio was higher in neonates with acute BIND, it seems that the cutoff point is not superior to the TSB level for predicting acute BIND. Comparing TSB and B/A ratio, the accuracy of these parameters is the same for predicting acute BIND. Experts suggested that in the absence of commercial assays for free bilirubin, the B/A ratio can be used in combination with TSB in the management of icteric neonates[14, 16]. Based on our results, we suppose that use of B/A ratio in conjunction with TSB can improve the specificity and prevent unnecessary invasive therapy such as exchange transfusion.

Present study has a few limitations. The main limitation was using clinical findings for diagnosis solely. Paramedical imaging studies such as MRA, MRI, and ABR would add more relevant data to brain anatomic changes.

We did not check albumin with bilirubin routinely, so gathering sufficient samples was difficult. Further studies with higher number of samples are recommended.

Conclusion

Using B/A ratio in conjunction with TSB can improve the accuracy of prediction of bilirubin-induced neurologic dysfunction and prevent unnecessary invasive therapy such as exchange transfusion in icteric neonates.

Acknowledgment

We thank greatly nurses of the neonatal unit in Children's Medical Center for their unreserved cooperation.

Conflict of Interest

None

References

- 1.el-Beshbishi SN, Shattuck KE, Mohammad AA, et al. Hyperbilirubinemia and transcutaneous bilirubinometry. Clin Chem. 2009;55(7):1280–7. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.121889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cabra MA, Whitfield JM. The challenge of preventing neonatal bilirubin encephalopathy: a new nursing protocol in the well newborn nursery. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2005;18(3):217–9. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2005.11928070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhutani VK, Johnson L, Sivieri EM. Predictive ability of a predischarge hour-specific serum bilirubin for subsequent significant hyperbilirubinemia in healthy term and near-term newborns. Pediatrics. 1999;103(1):6–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhutani VK, Gourley GR, Adler S, et al. Noninvasive measurement of total serum bilirubin in a multiracial predischarge newborn population to assess the risk of severe hyperbilirubinemia. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2):E17. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.2.e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro SM. Definition of the clinical spectrum of kernicterus and bilirubin-induced neurologic dysfunction (BIND) J Perinatol. 2005;25(1):54–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wennberg RP, Ahlfors CE, Bhutani VK, et al. Toward understanding kernicterus: a challenge to improve the management of jaundiced newborns. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):474–85. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw E, Grenier D. Prevention of kernicterus: new guidelines and the critical role of family physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(4):575–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarici SU, Saldir M. Genetic factors in neonatal hyperbilirubinemia and kernicterus. Turk J Pediatr. 2007;49(3):245–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shapiro SM, Bhutani VK, Johnson L. Hyperbilirubinemia and kernicterus. Clin Perinatol. 2006;33(2):387–410. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manning D. American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for detecting neonatal hyperbilirubinemia and preventing kernicterus. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005;90(6):F450–1. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.070375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhutani VK. Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia and the potential risk of subtle neurological dysfunction. Pediatr Res. 2001;50(6):679–80. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200112000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daood MJ, McDonagh AF, Watchko JF. Calculated free bilirubin levels and neurotoxicity. J Perinatol. 2009;29(Suppl 1):S14–9. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostrow JD, Pascolo L, Tiribelli C. Reassessment of the unbound concentrations of unconjugated bilirubin in relation to neurotoxicity in vitro. Pediatr Res. 2003;54(6):926. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000103388.01854.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smitherman H, Stark AR, Bhutani VK. Early recognition of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia and its emergent management. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;11(3):214–24. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahlfors CE. Criteria for exchange transfusion in jaundiced newborns. Pediatrics. 1994;93(3):488–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hulzebos CV, van Imhoff DE, Bos AF, et al. Usefulness of the bilirubin/albumin ratio for predicting bilirubin-induced neurotoxicity in premature infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2008;93(5):F384–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.134056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amin SB, Ahlfors C, Orlando MS, et al. Bilirubin and serial auditory brainstem responses in premature infants. Pediatrics. 2001;107(4):664–70. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Govaert P, Lequin M, Swarte R, et al. Changes in globus pallidus with (pre)term kernicterus. Pediatrics. 2003;112(6 Pt 1):1256–63. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheidt PC, Graubard BI, Nelson KB, et al. Intelligence at six years in relation to neonatal bilirubin levels: follow-up of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Clinical trial of phototherapy. Pediatrics. 1991;87(6):797–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim MH, Yoon JJ, Sher J, et al. Lack of predictive indices in kernicterus: a comparison of clinical and pathologic factors in infants with or without kernicterus. Pediatrics. 1980;66(6):852–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Odell GB, Cukier JO, Ostrea EM, et al. The influence of fatty acids on the binding of bilirubin to albumin. J Lab Clin Med. 1977;89(2):295–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robertson A, Karp W, Brodersen R. Bilirubin displacing effect of drugs used in neonatology. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1991;80(12):1119–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1991.tb11798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]