Abstract

Objective

Acute Poisoning in children is still an important public health problem and represents a frequent cause of admission in emergency units. The epidemiological surveillance specific for each country is necessary to determine the extent and characteristics of the problem, according to which related preventive measures can be taken.

Methods

The present retrospective study describes the epidemiology of accidental and suicidal poisonings in a pediatric population admitted to the Pediatric Emergency Department of Eskisehir Osmangazi University Hospital during the year 2009.

Findings

Two hundred eighteen children were reffered to the emergency department due to acute poisoning. 48.4% of patients were boys and 51.6% were girls. The majority of cases were due to accidental poisoning (73.3% of all patients). Drugs were the most common agent causing the poisoning (48.3%), followed by ingestion of corrosive substance (23.1%) and carbon monoxide (CO) intoxication (12.5%). Tricyclic antidepressant was the most common drug (11.7%). Methylphenidate poisoning, the second common drug. 262 patients were discharged from hospital within 48 hours.

Conclusion

Preventable accidental poisonings are still a significant cause of morbidity among children in developing countries. Drugs and corrosive agents are the most frequent agents causing poisoning.

Keywords: Poisoning, Emergency, Children, Intoxication

Introduction

Acute Poisoning in children is still an important public health problem and represents a frequent cause of admission in emergency units. The incidence of childhood poisoning in various studies ranges from 0.33% to 7.6% [1, 2]. Poisoning is most commonly observed at 1–5 years of age and these children constitute 80% of all poisoning cases [3, 4]. In the first year of life, the main causes of poisoning are medications given by parents. At 2–3 years of age, house cleaning products cause most cases of poisoning, at 3–5 years of age, the medications kept in the cupboard or left open are the main causes of poisoning, and at school age and during adolescence, medications used for committing suicide are the main cause of poisoning [4].

The mortality rate due to poisoning is 3–5%[1, 2, 4]. The pattern and main risks of acute poisoning change with time according to age, and they differ from country to country. Thus epidemiological surveillance specific for each country is necessary to determine the extent and characteristics of the problem, according to which related preventive measures can be taken.

The purpose of this study was to describe the epidemiology, pattern, duration and the results of treatment of poisoned patients who were admitted to a pediatric referral hospital.

Subjects and Methods

The present retrospective study describes the epidemiology of a pediatric population with accidental and suicidal poisonings admitted to the Pediatric Emergency Department of Eskisehir Osmangazi University Hospital, which is a tertiary hospital in central Anatolia providing health care for at least 4 cities, during the year 2009. All pediatric patients under 17 years of age presenting to the emergency department from January to December 2009 were investigated retrospectively. Acute food poisoning patients were excluded from research group. Data were obtained by individual examination of the files, transferred to standard forms and submitted to statistical analysis.

The age and sex of the patients, duration between ingestion of poison and admission to hospital, manner of poisoning, poison agents, and duration of hospitalization are evaluated. In statistical evaluation, SPSS 15.0 Windows program was used. Chi square, Pearson correlation analysis and variance analysis were employed in the analysis of the data. Approval of local ethical was obtained related with this research.

Findings

Three hundred and twenty one children visited the emergency department due to acute poisoning. Complete clinical data were obtainable only for 281 patients. The poisoned patients represented 2.31% (281/12150) of overall emergency unit visits during the year 2009.

Age and Sex

The patients consisted of 136 (48.4%) boys and 145 (51.6%) girls. The mean age of all patients was 5.35±3.1. One hundred and thirty eight children, forming 49.1% of all patients, were under four years of age. Ninety nine patients were over 10 years of age (35.2% of all patients). According to age groups, 66.6% of cases older than 10 years of age were girls. In the poisoned patients under 4 years of age, male to female ratio was significantly higher when compared with the other age groups (χ2=21.6, P<0.001).

Mode of Poisoning

The majority (73.3%) of cases were accidental poisonings. Seventy two cases of poisoning occurred as suicide attempts and 73.6% (n=50) of those patients were girls.

The age of 97.2% (n=70) of patients attempting suicide was over 9 years. Only two patients were poisoned due to therapeutical error (Table 1). One case was poisoned due to overdose of chloral hydarte used for sedation during magnetic resonance imaging and the other case by pseudoephedrine overdose.

Table 1.

Manner of poisoning according to age groups

| Age Groups | Accidental n (%) | Suicide attempts n (%) | Therapeutical n (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–4 | 135 (65.2) | 0 | 1 (50) | 136 (48.4) |

| 5–9 | 42 (20.3) | 2 (2.8) | 0 | 44 (15.6) |

| >10 | 30 (14.5) | 70 (97.2) | 1 (50) | 101 (36) |

| Total | 207 (100) | 72 (100) | 2 (100 | 281 (100) |

Route of Poisoning and Monthly Distribution

The most common route of poisoning was the ingestion of poison in 243 (86.5%) patients. The remaining was poisoned by respiratory route (13.35%, n=38).

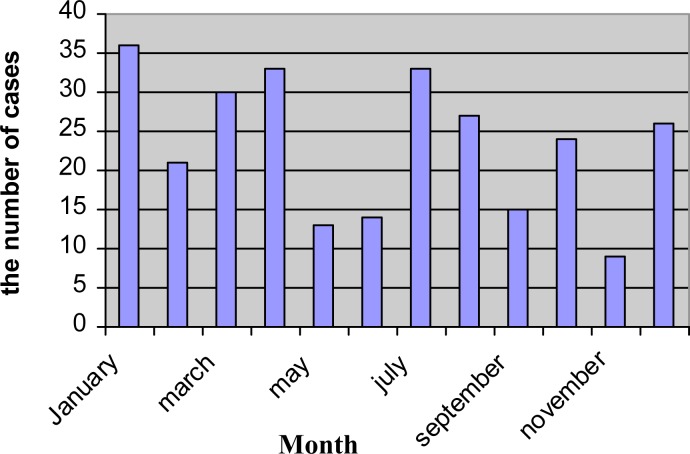

Poisoning occurred mostly in winter and peak (12.8%) of poisoning was observed in January. November was the month of the lowest rate of poisoning (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Monthly distribution of acute poisoning

Time Elapsed Before Admission

Of all cases referred to emergency unit 70.8% arrived within the first two hours and 95.7% in the first six hours following poisoning. Parents of only 95 (33.3%) children were aware that their children were poisoned because they had been witnesses of the event.

Nausea and vomiting was the most common complaint of cases at presentation to hospital (42.3%, n=119), followed by unconsciousness (18.1%, n=51). After stabilization of patient's condition a detailed history was obtained. If parents stated that the child had been poisoned, medical treatment was initiated immediately. If the child had no poisoning history, or signs and symptoms of other diseases were present, toxicological studies were undertaken including blood and urine panels.

Agents Involved

Drugs were the most common agents causing poisoning (48.4%, n=136), followed by ingestion of corrosive substances (23.1%, n=65), carbon monoxide (CO) intoxication (12.5%, n=35), hydrocarbons (5.7%, n=16), insecticides (3.9%, n=11), plants (3.9% n=11) and alcohol (2.5%, n=7). Among poisonings caused by drugs 38.9% (n=53) of cases were due to multiple medications. Tricyclic antidepressant was the most common drug (11.7%, n=33) causing poisoning. Methylphenidate (17.6% n=24) and analgesics (14.7%, n=20) were other common medications (Table 2). None of poisonings was due to opioid medications. Poisoning caused by corrosive substances was more common in children under 4 years of age (72.3%, n=47) than in other age groups.

Table 2.

Agents causing poisoning

| Agent | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Drugs | 136 (48.4) |

| Corrosive substances | 65 (23.1) |

| Carbon monoxide | 35 (12.5) |

| Hydrocarbons | 16 (5.7) |

| Plants | 11 (3.9) |

| Insecticides | 11 (3.9) |

| Alcohol | 7 (2.5) |

Treatment and Duration of Hospital Stay

In most of cases, treatment was non-specific, including general decontamination and supportive-symptomatic therapy. Gastric lavage was performed in 116 children who had ingested poison. Esophagoscopy was performed in 65 patients who had ingested corrosive substances. Two patients developed esophageal stricture. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy was the treatment modality for twelve CO poisoned cases. Two hundred and sixty two patients were discharged from hospital within 48 hours. Only 10 children stayed in hospital more than 72 hours. None of our patients died as a result of poisoning. All were well except for two patients who developed esophageal stricture.

Discussion

Acute poisoning is one of the important causes of emergency unit admissions. Identification and documentation of epidemiological aspects and other variables in childhood poisoning are of great importance for treatment plan and determination of proper preventive measures. Eskisehir Osmangazi University Hospital is the biggest referral hospital for children in central Anatolia, Turkey. Acute poisoning accounted for 2.31% of the cases referred to pediatric emergency unit. Poisoning has been reported to range from 0.21–6.2% in Turkey[4]. In western countries, the percentage of pediatric emergency service admission for poisoning was 0.28% to 0.66%[6–7]. According to these findings it is suggested that poisonings are still an important issue in Turkey.

In this study the male/female ratio was 1.06. Female predominance was present after ten years of age. Andiran and Sarikayalar found that in 489 poisoning cases poisonings <10 years of age were more frequent in males whereas poisonings >10 years of age were more common in females [8].

In several studies, it has been reported that 51.4%–73.3% of all poisoning cases observed in Turkey involved children <5 years of age [4, 5, 8, 9]. Similar findings have been reported from developed and developing countries [10]. The present study showed that approximately half of the patients were less than four years old. In this age group, males were predominant. Ozdogan et al found that the highest incidence of poisoning was in age group 13 months to 4 years [9].

In this age group, putting small foreign objects like drugs into mouth by children can cause poisoning. As in the literature, our research revealed that the most common (86.5%) route of poisoning was the ingestion of poison; drugs are the most common agent of poisoning in all ages.

Medications are the most common poisonous agent in children [1–5]. In our study 48.4% of all poisonings were due to drugs. Tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline were the most common drugs. This may be due to placing the drug in easily accessible places.

Methylphenidate, one of the first treatment modalities used in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, was the second common cause of drug related poisonings. This might be related with relatively high prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, with an estimated rate of 3% to 6% of school-aged children [11]. With increasing therapeutic use of methylphenidate, the potential exists for an associated increase in its adverse effects and poisoning. According to our best knowledge this is the first report in which methylphenidate is found to be the second common drug responsible for poisoning in children.

Carbon monoxide intoxication was found in 12.5% of all cases. Carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning is one of the most common causes of morbidity and mortality due to poisoning in Turkey and all over the world. The frequency of CO poisoning has been reported between 3.6–13.2% among childhood poisonings and between 58.2–75% among fatal childhood poisonings. The major sources of CO are faulty furnaces, inadequate ventilation of heating sources, and exposure to engine exhaust gases.

The clinical presentation of CO poisoning may be various and nonspecific. Mild clinical signs and symptoms associated with CO poisoning are headache, dizziness, weakness, lethargy, and myalgia; however, severe signs and symptoms such as blurred vision, syncope, convulsion, coma, cardiopulmonary arrest and death can also accompany CO poisoning[12]. Because of these various signs and symptoms, blood gas analysis must be performed in every child presented with unconsciousness.

We retrospectively searched the emergency unit admissions during a year and found that most admissions were in January. Unlike our results, Andiran and Sarikayalar[8] reported that most poisonings occurred in May. We speculate that during winter children spent much more time in closed places where drugs are accessible. Most (95.7%) of our patients presented within six hours following poisoning. However, only 33.3% of parents were aware of poisoning.

Poisonings in children might be accidental or as suicide attempts. In general, it was reported that the incidence of adolescent suicides in Turkey was between 5.1% and 16.3% [4, 8]. Suicide is not only a problem in developing countries but more in developed countries. In USA, suicide is the third most common cause of death in adolescents [13]. It can also be associated with the strict forbiddance of suicide by Islam, the religious practice of the majority of our population. In Turkey, accidental usage of drugs constituted the majority (78.1–93.8%) of poisonings. The present study showed that 73.3% of all poisonings were accidental and only 25.6% occurred as suicide attempt.

Supportive-symptomatic therapy was applied to most of patients. Gastric lavage should not be employed routinely [14]. It should be considered only within the first 60 minutes of ingestion [15]. Gastric lavage was performed in 41.2% of the patients in this study, although 70.8% of all cases came to emergency unit within the first two hours. Hyperbaric oxygen was given to 12 children poisoned with CO who had carboxyl hemoglobin levels over 25%. No adverse effect of hyperbaric oxygen therapy developed in these patients.

The mortality rate due to acute poisoning ranges from 7.6% to 0.4% in literature[1, 2, 4]. Fortunately none of our patients died. Only two of our children developed esophageal sequel after poisoning. This relatively good prognosis might be attributed to the fact that 95.7% of our cases visited emergency unit within 2 to 6 hours following poisoning.

Our research has some limitations. It was done retrospectively. So, it is possible that not all medical data have been recorded into the files of patients in emergency unit.

Conclusion

Preventable accidental poisonings are still a significant cause of morbidity among children in developing countries. Drugs and corrosive agents are the most frequent agents causing poisoning.

Conflict of Interest

None

References

- 1.Agarwal V, Gupta A. Accidental poisoning in children. Indian Padiatr. 1984;11(9):617–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buch NA, Ahmed K, Sethi AS. Poisoning in children. Indian Padiatr. 1991;28(5):521–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petridou E, Kouri N, Ploychronopoulou A, et al. Risk factors for childhood poisoning: a case control study in Greece. Inj prv. 1996;2(3):208–11. doi: 10.1136/ip.2.3.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mutlu M, Cansu A, Karakas T, et al. Pattern of pediatric poisoning in the east Karadeniz region between 2002–2006: increased suicide poisoning. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2010;29(2):131. doi: 10.1177/0960327109357141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bicer S, Sezer S, Cetindag F, et al. Evaluation of acute intoxications in pediatric emergency clinic in 2005. Marmara Medical J. 2007;20(1):12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mintegi S, Fernández A, Alustiza J, et al. Emergency visits for childhood poisoning: a 2-year prospective multicenter survey in Spain. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22(5):334–8. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000215651.50008.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burillo-Putze G, Munne P, Dueñas A, et al. National multicentre study of acute intoxication in emergency departments of Spain. Eur J Emerg Med. 2003;10(2):101–4. doi: 10.1097/01.mej.0000072640.95490.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andiran N, Sarikayalar F. Pattern of acute poisonings in childhood in Ankara: what has changed in twenty years? Turk J Pediatr. 2004;46(2):147–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozdogan H, Davutoglu M, Bosnak M, et al. Pediatric poisonings in southeast of Turkey: epidemiological and clinical aspects. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2008;27(1):45–8. doi: 10.1177/0960327108088975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsalkidis A, Vaos G, Gardikis S, et al. Acute poisoning among children admitted to a regional university hospital in Northen Greece. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2010;18(4):219–23. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wigal SB, Chae S, Patel A, Steinberg-Epstein R. Advances in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a guide for pediatric neurologists. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2010;17(4):230–6. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yarar C. Neurological effects of acute carbon monoxide poisoning in children. J Pediatr Sci. 2009;1(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guavin F, Bailey B, Bratton Sl. Hospitalization for pediatric poisoning in Washington State, 1987–1997. Arch Pediatr Adolsc Med. 2001;155(10):1105–10. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.10.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krenzelok E, Vale A. Position statements: gut decontamination. American Academy of Clinical Toxicology; European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1997;35(7):695–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powers KS. Diagnosis and management of common toxic ingestions and inhalations. Pediatr Ann. 2000;29(6):330–42. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-20000601-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]