Abstract

In 2011, research educators face significant challenges. Training programs in Clinical and Translational Research need to develop or enhance their curriculum to comply with new scientific trends and government policies. Curricula must impart the skills and competencies needed to help facilitate the dissemination and transfer of scientific advances at a faster pace than current health policy and practice. Clinical and translational researchers are facing also the need of new paradigms for effective collaboration, and resource sharing while using the best educational models. Both government and public policy makers emphasize addressing the goals of improving health quality and elimination of health disparities. To help achieve this goal, our academic institution is taking an active role and striving to develop an environment that fosters the career development of clinical and translational researchers. Consonant with this vision, in 2002 the University of Puerto Rico, Medical Sciences Campus School of Health Professions and School of Medicine initiated a multidisciplinary post-doctoral Master of Science in Clinical Research focused in training Hispanics who will address minority health and health disparities research. Recently, we proposed a curriculum revision to enhance this commitment in promoting competency-based curricula for clinician-scientists in clinical and translational sciences. The revised program will be a post-doctoral Master of Science in Clinical and Translational Research (MCTR), expanding its outreach by actively engaging in establishing new collaborations and partnerships that will increase our capability to diversify our educational efforts and make significant contributions to help reduce and eliminate the gap in health disparities.

Indexing terms: Research career development, clinical and translational research, minority health, health disparities, Hispanic researchers

INTRODUCTION

A decade ago, two basic science researchers of the University of Puerto Rico, Medical Sciences Campus (UPR-MSC), one from the School of Health Professions (SoHP) and one from the School of Medicine (SoM), invited well known physician-scientists and health professionals to join them in creating an academic program to develop clinicians, basic scientists and physicians interested in pursuing a clinical research career (1). As an outcome of this initiative, the post-doctoral Master of Science in Clinical Research (MSc) program was established with the support of a one-year planning grant awarded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) R21AR48043. The MSc program’s benchmark for its development was the clinical research program established at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine at Minnesota, with whom UPR-MSC leadership maintains a close partnership. From its beginning, the MSc program has been visionary in its formulation: To implement an accredited post-doctoral Master of Science in Clinical Research program. The two-year curriculum will combine intensive didactic and mentored clinical research training that will produce well-trained researchers who can lead clinical research studies addressing health disparities among American people, mainly the Hispanic population (2).

Several published studies have shown that integration of basic and clinical research is needed to effectively use the knowledge acquired through scientific discoveries to the advantage of population health (3–5). Thus, the term translational research was coined to express the concept or process that facilitates the transfer of scientific discoveries into practical applications for the benefit of population health (6–9). It is commonly thought that discoveries typically begin with basic (bench) research and then progress to the clinical level. However, translational research is bidirectional, where basic scientists provide clinicians with new concepts to apply while treating patients and assess their effectiveness; clinicians make novel observations generating new avenues of research that are answered through basic research (10). For this communication to occur effectively, new opportunities for education, training and interaction among individuals from multiple disciplines to answer complex research questions must be created. The creation of clinical and translational research academic programs responds to this need, increasing effective communication, respect and trust between clinical and basic researchers, establishing cooperative work environments, facilitating the translation of new knowledge (11, 12).

After having met with representatives of the research community, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) established a mechanism that is expected to catalyze the development of clinical and translational sciences. The outcome was the launching of the Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) Consortium in October 2006. To assist existing clinical research academic programs, the NIH National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) asked a group of experts to work in the development of the core competencies that define a Clinical and Translational Researcher. This multidisciplinary and multi-institutional working group, which included the active participation of Dr. Estape, identified 14 core areas and 101 competencies that define the basic knowledge, skills, and attributes that a master’s-level candidate should attain while training to become a clinical and translational researcher (13).

As a result of this NIH-NCRR initiative, the leading research academic institutions have been revising their curricula to incorporate translational competencies into their clinical research programs. Great efforts are directed to maximize the use of resources to develop, advance, and nurture a cadre of well-trained multi- and inter-disciplinary investigators (14, 15). Key to the success of these investigators is the development of collaborations with effective communication.

AIMS

The University of Puerto Rico, Medical Sciences Campus (UPR-MSC) post-doctoral Master of Science in Clinical Research (MSc) program has been supported by two five-year grant awards of NIH Clinical Research Education and Career Development (CRECD) in Minority Institutions (R25 RR17589; 2002–2012). The goals of the MSc program are consonant with NIH intended goals to facilitate multidisciplinary research teams that will collaborate in the translation of research findings to improve individual quality of life. The goals of the MSc program are to:

Prepare independent and committed clinical investigators

Develop multidisciplinary scientific teams

Reduce health disparities

Improve quality of life

The MSc program leadership revised the present curriculum to reflect the most recent trends that define clinical and translational science as a new discipline in the offering of a post-doctoral Master of Science in Clinical and Translational Research (MCTR) in the near future. This program will remain as a joint degree program between the Schools of Health Professions and Medicine and will maintain the same goals. The scope of research sponsored by the MCTR program will continue to address minority health and health disparities research through basic, clinical, and behavioral approaches. The revised competency-based curriculum will continue to be aimed at the development of six competency domains with the incorporation of translational research in the graduates’ profile (Table 1). This program will continue to focus on training investigators who will be able to lead and expand clinical research in Puerto Rico targeting specific health conditions of high priority to the Hispanic population and the mortality and morbidity trends in Puerto Rico. In addition, the MCTR program will continue its commitment to education and training of faculty from different disciplines focused on relevant and critical health issues. This will allow more interaction among disciplines, enhance team approach to problem solving and foster interdisciplinary collaboration.

Table 1.

Clinical and Translational Researcher Competencies

| MCTR program |

|---|

| 1.0) Be able to develop and implement ethnically and culturally appropriate clinical and translational research aimed at reducing health disparities in Hispanic populations; |

| 2.0) Conduct ethically responsible clinical and translational research; |

| 3.0) Build and lead effective collaborative networks in one’s area(s) of clinical and translational research interest; |

| 4.0) Communicate effectively orally and in writing; |

| 5.0) Be able to work collaboratively, interdependently, and effectively with individuals from other disciplines on the clinical and translational research team; and |

| 6.0) become a lifelong self-sufficient learner. |

SCIENTIFIC ACCOMPLISHMENTS

At present, the post-doctoral Master of Science in Clinical Research (MSc) is the only multidisciplinary NIH supported academic degree offering training and career development in clinical research in Puerto Rico. The program is open to qualified candidates from universities, industry, government and private organizations. Since 2002 the MSc program has achieved many goals including: 1) developing a solid clinical research curriculum; 2) increasing the number and diversity of Hispanic clinical researchers; 3) sponsoring research addressing health disparities such as cancer, HIV, diabetes, respiratory, cardiovascular diseases, oral health and mental health; 4) establishing local and external collaborations; and 5) developing a strong research component with an innovative mentor–mentee program.

The post-doctoral MSc program is designed to provide a two-year competency-based curriculum that consists of teaching strategies that includes: didactics, a mentoring system, a research project, and a seminar series. The curriculum is integrated effectively into a program of study designed to prepare well-trained researchers competent in clinical and translational research. The activities are designed to foster interdisciplinary collaboration and promote teamwork in problem solving. The format of the academic program addresses the needs of practicing health professionals by providing components of the courses by Internet and videoconferencing, as well as non-traditional scheduling (evenings and Saturdays). Most importantly, the MSc curriculum is consonant with NIH intended goals to facilitate multidisciplinary research teams that will collaborate in the translation of research findings. The program emphasizes opportunities that allows interaction of individuals from multiple disciplines to engage in networking activities that will result in better communication, respect and trust between clinical and basic researchers. Since 2003 to 2011, the MSc program has admitted 55 Scholars from multiple disciplines and specialties, with 53% of them medical doctors (Table 2).

Table 2.

MSc discipline diversity in Scholars admitted from 2003–2011

| Discipline | Specialty | Total # Scholars |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Doctor (MD’s) | General Practice (5), Emergency Medicine. (3), Pediatrics (3), Ob/Gyn (3), Gastroenterology (3), Orthopedic Surgery (2), Internal Medicine (2), Pediatric Surgery (1), Urology (1) Neonatology (1), Immunology (1), Gerontology (1), Family Medicine (1), Psychiatry (1) Neurology (1)* | 29 |

| Dental Medicine | Dentistry (3), Prosthodontics (2), Oral Implantology (1), Orthodontics (1), Pediatrics (1) | 8 |

| PhD’s Clinical and Basic Sciences | Clinical Psychology (5), Exercise Physiology (1), Physiology (1), Chemistry (1) | 8 |

| Allied Health | Speech Pathology, EdD (1), Occupational Therapy, PhD (1) Nutrition, EdD (1), Physical Therapy, PhD (1) * | 4 |

| Public Health | Environmental Health (2) | 2 |

| Pharmacy | Pharmacology (1), Pharm D(1) | 2 |

| Nursing | MD with Nursing degree* | 1 |

| Other | Veterinary medicine (1) | 1 |

| Total | 55 |

Three Scholars left the MSc program after admission due to personal reasons.

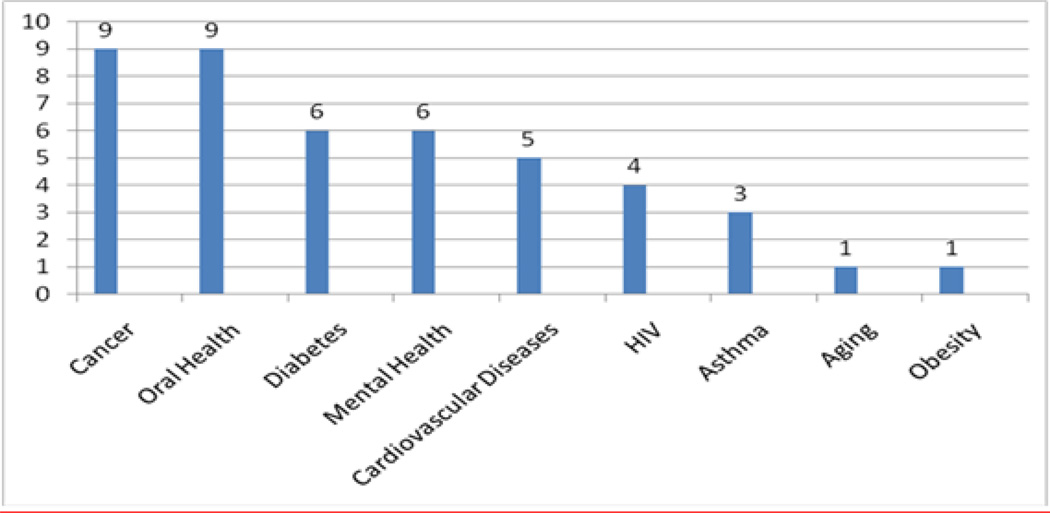

The first year curriculum is designed to provide the MSc Scholar with the knowledge and experience to develop an individualized research project under the supervision of a Mentor and Research Committee. The second year is mainly devoted to research activities to allow the Scholar to develop the skills necessary to carry out their original research protocol. Table 3 shows the research career development process that the program has designed for MSc graduates to be qualified to plan sound clinical investigations focused on health disparities. Throughout the training program, particular attention is devoted to societal and global issues associated with health disparities and underserved populations. The areas targeted for research have been: cardiovascular, cancer, HIV, respiratory diseases, diabetes, aging, mental health/psychiatric disorders and oral health. The main research areas selected by the Scholars 2003–2010 are shown in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Validation of Scholar’s competencies: To demonstrate that the Scholar is competent (having theoretical knowledge and understanding and practical experience of a topic, s(he) will be able to complete/carry out the task concerned independently).

| YEAR 1 | |

| Certificates of HIPPA & Human Subjects Courses | |

| Research Committee Formed | |

| Research Question Presentation | |

| Research Design Presentation | |

| Research Proposal Approval by Research Committee | |

| Presentation of Research Proposal | |

| IRB Submission | |

| Submission of Budget with Justification to program | |

| YEAR 2 | |

| Progress Reports | |

| Presentation at a local, national or international meeting | |

| Final Oral presentation | |

| Manuscript Submission as first Author to a peer review journal | |

| Publication of manuscript | |

Figure 1.

Postdoctoral Master of Science in Clinical Research Scholars 2003–2010 Research Area of Interest

The Scholar is evaluated on the traditional dimensional changes of knowledge, skills, and attitudes, and on outcomes related to becoming an independent clinical researcher. The Scholar’s outcome evaluation determines the extent to which the MSc competency-based curriculum, the mentoring system, and the overall program enable the Scholars to achieve the outcomes such as:

Knowledge, skills, and attitudes identified by each course faculty, mentor, and research committee.

Research outcomes including scientific presentations, peer–reviewed publications, public domain publications, recognitions and honors, externally funded clinical research projects.

Career outcomes such as the percentage of Scholars occupying academic positions with research release time.

According to recent NIH-NCRR guidelines to determine the effectiveness of research career development and the extent to which program goals are achieved, evaluation outcomes must include specific milestones in terms of the career outcomes of participating scholars. The evaluation of success of a career development program is recommended to be carried out after seven years after the Scholar’s completion of the program and includes:

Career outcomes of participants in terms of publications that impact health disparities; and securing external grant support;

Contributions made in the field of clinical research impacting health disparities

Diversity of participants

Capacity to create a stable environment for training clinical researchers who can address health disparities experienced by underrepresented minorities

Impact of the program in the career outcomes of participants – do they pursue research?

Dissemination of best practices and noteworthy outcomes in educating and mentoring participating scholars to become clinical investigators

Mentorship is a difficult process to achieve, even in the most advantaged institutional settings. The strength of the relationship between the mentor-mentee is crucial for the success of the Scholar’s research career development. The conceptualization of a mentoring team of local researchers with national/international researchers has been key in the successful development of the Scholar as clinical researcher. Table 4 presents a brief summary of the contributions of MSc graduates with their mentors’ affiliations during the 3–5 years after graduation in terms of publications, honors and awards and grants funded. This last measure is a challenge to be addressed. The interaction with mentors and faculty from other institutions enhances our research and academic capabilities. The program has expanded the number of faculty members using the team teaching approach in many of its didactic courses. In addition to the faculty that participate in the offering of the didactic courses, the program sponsors and helps develop educational activities with other programs and invites recognized clinical researchers to share their experiences with the faculty and Scholars.

Table 4.

MSc Graduates from 2006 to 2008 and their achievements.

| Graduates /year |

Disciplines | Mentors’ Affiliations | Publications | Honors and Awards |

Grants Obtained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9/2006 | 3MD, 1EdD, 3PhD, 2DM | UPR-MSC (2), Mayo Clinic (2), Center of Disease Control, University of Maryland, University of Utah, University of Venezuela | 20 | 15 | 7 |

| 6/2007 | 4MD, 1EdD, 1DM | UPR-MSC (4), Center of Disease Control, PR Diabetes Center | 16 | 15 | 0 |

| 7/2008 | 1MD, 2PhD, 4DM | UPR-MSC (6), New York University | 14 | 5 | 1 |

Last Update: June 2010

The UPR Program has been successful in developing a strong partnership with the graduate clinical research program at Mayo Clinic College of Medicine (Rochester, MN.). Mayo Clinic’s Clinical Research program’s leadership has been an active partner in writing the proposal to create, develop and establish the UPR Master of Science in Clinical Research. Their program was used as benchmark for our grant and the partnership with Mayo Clinic has continued succesfully. This strong partnership includes activities such as their leaders’ participation in the program’s Executive and Curriculum Advisory Committees, participation of their faculty as mentors and lecturers, and the UPR MSc graduates have been included as candidates to obtain the support and inter-institutional collaboration provided by Mayo Clinic. This partnership has played a leading role in increasing the minority leaders of the multidisciplinary clinical research teams of the future that will translate biomedical discoveries into improved health for the nation and help decrease health disparities.

Another initiative that has developed into a strong collaboration is the participation of faculty and Scholars of the University of Vermont, School of Medicine in the MSc program Fridays’ Multi-institutional Video Conference Seminars (16). These seminars allow the Scholars to enhance their communication skills and receive critiques for their research projects. Both partnerships have provided us the opportunity to increase the depth and breadth of training and improve the overall quality of the educational experience. The MSc program is strongly supported by the UPR institutional research centers, UPR-MSC Schools and Departments. As an example, the Assistant Deanship of Research of the UPR School of Dental Medicine has been instrumental in the admission of two international Scholars supported by a Fellowship from the School of Dentistry, University of Costa Rica at San Jose. MSc Scholars are also supported by funds from the NIH-National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD): the SoM Health Services Research and the SoHP and SoM Hispanics in Research Capability (HiREC) Endowment programs.

The program’s administrative infrastructure consists of several committees. The Executive Committee is composed of: Dr. Estela S. Estape (Director) ; Dr. Walter Frontera (Co-Director) ; Dr. Clemente Díaz (Associate Director); Dr. Barbara Segarra (Academic Coordinator) ; Mrs. Rafaela Berrios (Administrative Coordinator) and Dr. Ruben Garcia, Dr. Adriana Baez, Dr. Ruth Rios, and Dr. Margarita Irizarry. The Executive Committee continuously monitors and evaluates the overall effectiveness of the MSc program through the input from the Evaluation Committee and External Advisory Committee. Other committees such as Admissions, Curriculum, and Research are activated as needed and provide their input to the Executive Committee as well.

The MSc program was successful in obtaining an ARRA administrative supplement for the CRECD grant R25 RR017589. Through this supplement, we developed tutorials in areas of need and workshops, provided faculty training and the necessary support to integrate web-based technologies to their course content and recorded Scholars ‘presentations as a personal evaluation tool for discussion with their mentors. In 2008, the Schools of Health Professions and Medicine were awarded a 15 million dollar NIMHD Endowment under the Program “Hispanics-In-Research Capability: SoHP & SoM Partnership (HiREC)” The HiREC Endowment is helping to expand the research capability of the UPR-MSC, enabling us to extend the program to two partner institutions, Ponce School of Medicine and Health Sciences (PSM/HS) and Universidad Central del Caribe (UCC) at Bayamon, increasing our scope of addressing research in health disparities in Puerto Rico. This last effort has been done in collaboration with an NIH-NCRR award received in 2010 to strengthen clinical research infrastructure in the island. Dr. Walter Frontera is the PI of this initiative and with this funding, the Puerto Rico Clinical and Translational Research Consortium (PRCTRC) was created. One of the fundamentals for an academic institution to receive this award is the requisite of having an accredited clinical research training program, such as the MSc. The PRCTRC represents consortia including the UPR-MSC and the PSM/HS and UCC, private academic institutions which also have NIH-NCRR Research Centers for Minority Institutions (RCMI) awards. Dr. Estela S. Estape is the leader of the PRCTRC key function Multidisciplinary Training and Career Development, which facilitated the creation of two HiREC/PRCTRC Clinical and Translational Scholar Research Awards to support one candidate from each of each consortium member institutions to be part of the MSc program. These new awards will help us to expand our outreach activities to other parts of the island.

PRESENT STUDIES AND PRELIMINARY RESULTS

The MSc curriculum had experienced minor changes since its implementation in 2003. However, last year a curricular revision was done following NIH recommendations for competencies that define the basic knowledge, skills, and attributes that a master’s-level candidate should attain while training to become a clinical and translational researcher. The curriculum sequence for the MCTR program will continue as a 30 semester credit academic program, designed to be completed in two years, including two summers. The didactic core component has 24 semester credits with the research component equivalent to a one-year research project and 6 semester credits. The proposed curriculum includes the creation of three new courses:

Scientific Communication in Clinical and Translational Research,

Introduction to Biomedical Informatics

Translational Research in Health Disparities.

This last course was developed using a multi-institutional and multidisciplinary approach. This experience was chronicled in a scientific manuscript, entitled “A Multi-Institutional, Multi-disciplinary Model for Developing and Teaching Translational Research in Health Disparities”, accepted for publication in the Journal of Clinical and Translational Science (in press).

The curriculum of the MCTR program is based on the NIH’s set of 14 core thematic areas. The general educational objectives are designed to support and enable scholars to acquire the skills, knowledge and attitudes required to address clinical and translational research. The general educational objectives are:

Clinical and Translational Research Questions: Be aware of clinical and translational research questions and gaps in health care to advance the application of basic science to clinical practice and create scientific questions through clinical observation.

Literature Critique: Critically evaluate and interpret clinical and translational literature for the preparation of grants, research proposals, articles, manuscripts, abstracts and presentations.

Study Design: Demonstrate the skills of problem solving, analysis, evaluation and critical thinking strategies in the design of clinical and translational research projects.

Research Implementation: Devise feasible and testable hypothesis to implement clinical and translational research project designs that are planned to be efficient and incorporate validity assessments and regulatory precepts.

Sources of error: Recognize sources of error that could impact reliability and validity in a study design.

Statistical Approaches: Understand basic principles of statistical methods and procedures to be able to work in collaboration with a biostatistician for the analysis of research findings and data management.

Biomedical Informatics: Understand the use of technology, informatics and electronic health record for seeking information; data processing, study design and analyses of high dimensional data.

- Responsible Conduct of research

- Clinical Research Ethics: Apply the basic principles of Bioethics in research: respect for autonomy, justice, beneficence and non-maleficence to assure the need for privacy protection throughout all phases of a study, maintain the decision-making capacity of participants, and ensure that there is a risk-benefit ratio that achieves a positive balance towards patient/subject benefit with the outcomes in clinical and translational research.

- Responsible Conduct of Research: Apply the rules and professional standards that govern human subject research including: Internal Review Board application processes, procedures and approval; voluntary informed consent; confidentiality and security in data collection, analyses and sharing; and protection of the patient/subject throughout all phases of clinical and translational research.

Scientific Communication: Master scientific writing and public speaking skills in order to effectively communicate research findings to the general public and scientific community and understand the importance of patents, patent applications, entrepreneurial innovations and technology transfer to the general public and the scientific community.

Cultural Diversity: Develop ethnically and culturally appropriate clinical and translational research aimed at reducing health disparities

Translational Teamwork: Build and lead effective collaborative networks among different disciplines to address together an important and challenging health issue.

Leadership: Recognize the importance of collaborative work between peers, mentors and mentees to foster innovation, creativity and willingness to be an independent/self-learner in clinical and translational research

Cross Disciplinary Training: Incorporate adult learning principles, mentoring strategies and competency-based instruction to the planning of educational activities in multidisciplinary clinical and translational research.

Community Engagement: Value the role of community engagement research, cultural and linguistic competence and health literacy as strategies for translating health research to communities and reducing health disparities.

SIGNIFICANCE

As an academic health center, the Medical Sciences Campus of the University of Puerto Rico is the academic leader in the development of Hispanic health professionals in Puerto Rico, the Caribbean, Latin America and the USA. The UPR-MSC comprises the six major health disciplines: medicine, allied health, dental medicine, public health, nursing and pharmacy. The Campus is within the Puerto Rico Medical Center, which includes the University District Hospital, Caribbean Cardiovascular Center, the Municipal Hospital, Psychiatric Hospital, Puerto Rico Cancer Center, Pediatric Hospital, VA Medical Center general and other specialty hospitals, ambulatory clinics and health facilities. The close proximity of these resources provides a unique opportunity for the integration of clinical and translational research with delivery of health services and health professions education. As educators, we are committed to maintaining our curricula in compliance with new scientific trends, professional standards as well as government policies and procedures. As proactive leaders, the MSc program is committed to continuing to develop an environment that fosters the career development of clinical and translational researchers. These investigators will make a significant contribution in areas such as the delivery of health services, early detection of disease, prevention of diseases, rehabilitation and the reduction and elimination of health disparities.

The MSc respond to the need to maintain an academic program of excellence in clinical and translational research that will foster collaborative educational efforts and research projects aimed at strengthening laboratory, patient-oriented, epidemiologic and outcomes research. Our present MSc program, and in the near future, the MCTR program, heighten the visibility of research in the University of Puerto Rico supporting the institutional efforts to enhance the training, educational, mentoring, and career development opportunities to individuals from underrepresented populations. More importantly, the program facilitates the development of a multi-disciplinary pool of clinical and translational Hispanic investigators with the skills to conduct health disparities research.

FUTURE PLANS

Creating a research program that fosters multidisciplinary collaboration and provides the competencies and skills in clinical and translational research is required not only for doctoral-level scholars in medicine and the health related disciplines, but also to candidates with non-health related doctorates, such as education, chemistry, physics, exercise physiology and others. This remains as one of our goals and we look forward to developing significant multidisciplinary collaborative initiatives. These efforts will help us achieve our program’s mission to improve the public’s health by increasing the quality and quantity of clinical and translational research. The Program will continue its efforts to establish collaboration with the pharmaceutical industry to provide training for personnel involved in clinical trials and with health care organizations, industry and other private academic institutions interested in expanding knowledge through partnerships in clinical and translational research (17). We expect that the successful outcomes of this program will motivate allied health, nursing, pharmacy and public health professionals to become interested in advancement of their research career, to serve as facilitators for the translation of basic and clinical research findings into better health care.

Diversity in the clinical/translational research team remains an important gap. An approach to address this need can be through increasing the participation of clinicians and other health professionals as partners in research with basic and applied scientists, as well as other disciplines. Academic institutions can help reduce this gap by supporting training, educational, mentoring, and career development programs in clinical and translational research for underrepresented individuals from health professions such as Allied Health, Nursing, Pharmacy and Public Health. As shown in Table 2, 67% of the 55 candidates admitted to the MSc program during 2003–2011 were from the Schools of Medicine (29) and Dental Medicine (8). This local trend in admissions is similar to the participation reported in Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) programs created by NIH-NCRR, where 66% of the participants are from medicine. Table 4 shows the approximate participation (%) of Allied Health, Nursing and Pharmacology (Pharmacy) and Public Health in the national pool of CTSA Investigators. In addition, this report also indicates that all CTSA’s Directors are MD’s or MD/PhDs. This analysis showing the underrepresentation of the health professions in the health research workforce was done by Dr. Estape using data published in the NCRR Annual Progress Report 2006–2008 including the first 38 CTSA institutions (18).

Taking into consideration the emphasis on improving health quality for all, with the need to transfer knowledge and scientific findings into population-based health benefits, and the need to reduce the economic burden of health care, we plan to:

Actively engage in the training and education of Hispanic health professionals to become part of the next generation of clinical and translational researchers.

Motivate Hispanic health professionals in becoming active partners in the clinical and translational research enterprise.

Continue to submit competitive applications to support training and career development activities.

Secure external funds, matched with institutional support, to provide research release time for young faculty.

Create venues for collaboration and partnerships in research education and training.

Provide scientific leadership, administrative management and coordination of efforts to maximize the productivity and outcomes of the clinical and translational research training activities in Puerto Rico.

CONCLUSION

As leaders of this Hispanic clinical and translational research enterprise, we recognize that promoting diversity in the biomedical, behavioral, clinical and social sciences research workforce is a key factor to improve our capacity to address and eliminate health disparities. As the only academic health center in Puerto Rico, we are responsible for the enhancing the research environment where scholars, faculty and investigators can interact as essential partners in healthcare teams with a common goal of improving human health.

The MSc program’s ultimate mission is to promote the development of multidisciplinary scientific teams working toward the attainment of two common goals:

Improvement in quality of life and

decrease and eliminate health disparities.

This program will serve as a significant tool in the translation of basic and clinical research findings into better health care and lifestyle. More recently, with the proposed curriculum revision (MCTR), we will expand its outreach by establishing new collaborations and partnerships. This will increase our capability to diversify our educational efforts. “Thus, we support the creation of partnerships of non-physician clinician-scientists, practicing physicians and basic scientists as an effective way to increase clinical research productivity at an academic health center” (1). We firmly believe that sharing resources and best models among institutions will accelerate the changes needed to address the complexities of a multidisciplinary curriculum addressing translational research and health disparities.

We thank all our dedicated mentors, co-mentors, faculty and administrators who have supported the program and especially to our Scholars, for their achievements are our outcomes: “Once a Scholar, always a Scholar!”

Table 5.

Interdisciplinary Representation of CTSA Investigators

| Disciplines | Total Number |

% of total |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical disciplines | 6,339 | 58 |

| Pediatric disciplines | 873 | 8 |

| Public health | 555 | 5.1 |

| Genetics | 270 | |

| Neuroscience | 243 | |

| Allied Health | 213 | 1.95 |

| Nursing | 172 | 1.58 |

| Pharmacology | 129 | 1.18 |

| Other | 2,083 | |

| Total | 10,877 |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the participation of the following faculty and personnel from the Medical Sciences Campus, University of Puerto Rico in the development of the MSc and MCTR programs: Mrs Rafaela Berrios (Administrative Coordinator), Dr. Ruben Garcia, Dr. Margarita Irizarry, Prof. Carlos Ortiz, Dr. Delia Camacho, Dr. Rosa Janet Rodriguez, Dr. Lourdes Soto de Laurido, Ms. Lizbelle de Jesus and Prof. Maria San Martin from the School of Health Professions; Dr. Pedro Juan Santiago Borrero, Dr. Jose Rodriguez-Orengo, Dr. Enid Garcia, Dr. Ricardo Gonzalez, Dr. Valerie Wojna, Dr. Raul Bernabe and Dr. Mary Helen Mays from the School of Medicine; Dr. Ruth Rios from the Graduate School of Public Health.

We also acknowledge the support of our committed collaborators: Dr. Augusto Elias Boneta from the School of Dental Medicine and Dr. Juan Carlos Zevallos from the School of Medicine; Dr. Richard McGee from Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine; Dr. Sherine Gabriel and Mrs. Karen Weaver from Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota; Dr. Ben Littenberg and Dr. Alan S. Rubin from University of Vermont; our CRECD partners, Dr. Alexander Quarshie from Morehouse School of Medicine, Dr. Magda Shaheen from Charles Drew School of Medicine, Dr. Rosanne Harrigan from University of Hawaii at Manoa, School of Medicine, and Dr. John Murray from Meharry School of Medicine; our NIH-NCRR program Health Scientist Administrator, Dr. Krishan K. Arora; and the NIH co-funders of the CRECD program for their support: National Center for Research Resources (NCRR); National Institute on Aging (NIA); National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS); National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI); National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

Funding sources of support for this work:

This work was supported in part by the following Public Health Service Grants from the National Institutes of Health: R21AR48043, R25RR17589, S21MD001830 and U54RR026139 at University of Puerto Rico.

Footnotes

“The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose”

Contributor Information

Estela S. Estape, School of Health Professions, Medical Sciences Campus, University of Puerto Rico

Barbara Segarra, School of Health Professions, Medical Sciences Campus, University of Puerto Rico

Adriana Baez, School of Medicine, Medical Sciences Campus, University of Puerto Rico

Aracelis Huertas, School of Health Professions and School of Medicine, Medical Sciences Campus, University of Puerto Rico.

Clemente Diaz, School of Medicine, Medical Sciences Campus, University of Puerto Rico.

Walter Frontera, School of Medicine, Medical Sciences Campus, University of Puerto Rico

REFERENCES

- 1.Estapé ES, Rodriguez-Orengo JF. Creation of two multidisciplinary clinical research academic programs at a minority academic health center. Clinical Research Perspectives, Association of Clinical Research Training Program Directors. 2004:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Estapé ES, Rodríguez-Orengo JF, Scott VJ. Development of Multidisciplinary Academic Programs for Clinical Research Education. Journal of Allied Health. 2005;34(2):55–70. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Association of American Medical Colleges. Clinical Research: a national call to action. Washington, D.C.: AAMC; 2000. Breaking the Scientific bottle neck. ( http://www.aamc.org/newroom/clinres/start.htm) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moskowitz J, Thomson JN. Enhancing the clinical research pipeline: training approaches for a new century. Academic Medicine. 2001;76:307–315. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200104000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woolf SH. The meaning of translational research and why it matters. JAMA. 2008;299(2):211–213. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pober JS, Newhouser CS, Pober JM. Obstacles facing translational research in academic medical centers. FASEB. 2001;15(13):2303–2313. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0540lsf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rustgi AK. Translational research: what is it? Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1285. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70488-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waldman SA, Terzic A. Clinical translational science 2020: innovation redefines the discovery-application enterprise. Clinical and Translational Science. 2011;4(1):69–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2011.00261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laure MS, Collins FS. Using science to improve the nation's health system: NIH's commitment to comparative effectiveness research. JAMA. 2010;303(21):2182–2183. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selker HP. Beyond Translational Research from T1 to T4: Beyond “Separate but Equal” to Integration (Ti) Clinical and Translational Science. 2011;3(6):270–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2010.00247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubio DM, Schoenbaum EE, Lee LS, Schteingart DE, Marantz PR, Anderson KE, Dewey-Platt L, Báez A, Esposito K. Defining Translational Research: Implications for Training. Academic Medicine. 2010;85(3):470–475. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ccd618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiner RS. Finding the path back to patient-oriented research in American medical academia. Clinical and Translational Science. 2011;4(1):7. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2011.00260.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Core Competencies in Clinical and Translational Research. CTSA website available at http://www.ctsaweb.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=home.showCoreComp.

- 14.Jackson RD, Gabriel S, Pariser A, Feig P. Training the translational scientist. Science Translational Med. 2010;2(63) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001632. 63mr2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borner F, Contractor N, Falk-Krzesinski HJ, Fiore SM, Hall KL, Keyton J, et al. A Multi-Level Systems Perspective for the Science of Team Science. Science Translational Med. 2010;2(49) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001399. 49cm24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Segarra B, Estape E. Multi-institutional Video Conference Seminars – University of Puerto Rico Perspective. Clinical Research Perspective, Association for Clinical Research Training. 2008;5(Issue 1):2. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Estape E, Frontera W. MEMO. 10. Vol. 12. Pharmaceutical Industrial Association (PIA); 2008. Clinical Research Degree Programs–UPR Medical Sciences Campus; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 18.NCRR Progress Report 2006–2008. http://ncrr.nih.gov/clinical_research_resources/clinical_and_translational_science_awards/publications/2008_ctsa_progress_report.pdf.