Abstract

Background. When schizophrenia patients have insufficient response to clozapine, pharmacological augmentation is often applied. This meta-analysis summarizes available evidence on efficacy of pharmacological augmentation of clozapine treatment in schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Methods. Only double-blind randomized controlled studies were included. Primary outcome measure was total symptom severity, and secondary outcome measures were subscores for positive and negative symptoms. Effect sizes were calculated from individual studies and combined to standardized mean differences (Hedges's g). Results. Twenty-nine studies reporting on 15 different augmentations were included. Significant better efficacy than placebo on total symptom severity was observed for lamotrigine, citalopram, sulpiride, and CX516 (a glutamatergic agonist). The positive effect of lamotrigine disappeared after outlier removal. The other positive findings were based on single studies. Significantly better efficacy on positive symptom severity was observed for topiramate and sulpiride. The effect of topiramate disappeared after outlier removal. Results for sulpiride were based on a single randomized controlled trial. Citalopram, sulpiride, and CX516 showed better efficacy for negative symptoms than placebo, all based on single studies. Conclusions. Evidence for efficacy of clozapine augmentation is currently scarce. Efficacy of lamotrigine and topiramate were both dependent on single studies with deviating findings. The effect of citalopram, sulpiride, and CX516 were based on single studies. Thus, despite their popularity, pharmacological augmentations of clozapine are not (yet) demonstrated to be superior to placebo.

Keywords: schizophrenia, augmentation, clozapine, resistant

Introduction

Although antipsychotic agents are effective in the majority of patients with schizophrenia, between one-fifth and one-third of patients have little, if any, benefit from them.1 Treatment of these patients has remained a persistent public health problem as medication-resistant patients are often highly symptomatic,2 have a severely reduced quality of life, and need extensive periods of hospital care.2 They also require a disproportionately high amount of the total health costs for schizophrenia.3,4

The landmark trial of Kane et al5 demonstrated superior efficacy for clozapine over other antipsychotic agents for this subgroup of medication-resistant patients, a finding that has now consistently been replicated.6–8 In order to optimize clozapine therapy, several studies have evaluated the relationship between clozapine blood levels and therapeutic response. Clozapine levels above 350–450 μg/ml are shown to be associated with superior treatment response than lower levels (reviewed by Schulte9). Although clozapine is considered the most efficient antipsychotic agent in refractory patients, as many as 40%–70% of these patients achieve only poor or partial response with it, even with adequate blood levels of clozapine.5,10–12 For these ultra-resistant patients, several treatment strategies can be followed, including psychotherapy,13 pharmacological augmentation,14 repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation,15 or electroconvulsive therapy.16 Augmentation of clozapine with another pharmacological substance is used frequently in clinical practice, despite the paucity of evidence that adding a second drug will enhance antipsychotic properties.17–20 Some of the most frequently prescribed augmentation components are lithium, sodium valproate, benzodiazepines, various selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), risperidone, haloperidol, and aripiprazole.21 Since clinicians quite routinely turn to pharmacological augmentation strategies when facing clozapine-resistant schizophrenia patients, a critical evaluation of the efficacy of pharmacological agents in augmenting clozapine treatment response is warranted.

There are numerous reports available regarding augmentation strategies in patients with poor or partial response to clozapine. Augmentation with conventional or atypical antipsychotics,22,23 various antidepressants,24,25 lithium,26 sodium valproate,27 carbamazepine,28 novel anticonvulsants,29 dopamine agonists,30 glutamate receptor agonists,31 mazindol,32 and omega-3 fatty acids33 have all been described as clozapine adjuncts in the treatment of resistant symptoms. The available literature addressing different augmentation strategies in clozapine-resistant patients seems promising at first glance because most reports suggest that therapeutic benefits can be gained.14,34–36 However, most studies are case reports, retrospective chart reviews, and small sampled uncontrolled trials. Such studies tend to produce a strong bias for positive results because negative reports in a case or a small sample are unlikely to be reported and/or published.37,38 In addition, the specific therapeutic response cannot be distinguished from placebo effects in uncontrolled studies. Meanwhile, there are only few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) available.

Perhaps as a result of the paucity of well-designed studies, expert guidelines have generally been reticent about augmentation strategies for clozapine-resistant patients.38,39 For example, the 2009 Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team has discussed adjunctive treatment strategies but argued that studies have failed to document sufficient efficacy to support a recommendation in patients with clozapine-resistant schizophrenia.40

Therefore, this study aims to review all double-blind randomized controlled studies available regarding the efficacy of pharmacological augmentation in clozapine-resistant patients, and perform meta-analyses on the efficacy of individual clozapine adjuncts when sufficient studies are available. By quantitatively summarizing the literature on clozapine augmentation strategies, this review aims to assess the efficacy of the different clozapine augmentation strategies in reducing persistent positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia.

Methods

Literature Search

This meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) Statement.41 The protocol of the search strategy can be viewed online (http://www.stemmenpoliumcutrecht.nl/). An electronic search was performed using Medline, Embase, PsychInfo, National Institutes of Health, ClinicalTrials.gov, Cochrane Schizophrenia Group entries in PsiTri (http://psitri.stakes.fi), and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

There were no year or language restrictions. The following basic search terms were used, both alone and in combinations: ‘schizophrenia,’ ‘clozapine,’ ‘resistant,’ ‘refractory,’ and the names of the particular pharmacological components used for augmentation. Additionally, the reference lists of the retrieved articles and relevant review articles were examined for cross-references. When necessary, corresponding authors were contacted to provide full details of study outcomes or scores for subgroups of patients treated with clozapine.

Inclusion

Consensus on the studies included was reached on the basis of the following criteria:

Randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled studies of at least 2 weeks duration regarding clozapine augmentation by a second drug.

Patients included had a diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or psychotic disorder not otherwise specified), according to the diagnostic criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 42 (DSM-III, DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, DSM-IV-TR, or International Classification of Diseases-9 or 10).

Patients were treated with a stable dose of clozapine for a minimum of 4 weeks before the study started. The use of comedication was permitted if dosage had been without changes for 4 weeks prior to study onset and during the study.

Studies reported sufficient information to compute common effect size statistics, ie, means and SDs, exact P, t, or z values (cf. Lipsey and Wilson43) or corresponding authors could supply these data upon request.

Crossover studies were not excluded in order to obtain as much information as possible.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was the mean change in total score on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale44 (PANSS) or the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale45 (BPRS). Secondary outcome measures included positive and negative symptom subscores of the PANSS or the BPRS or scores on the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms46 and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms47. Patient data of the last observation carried forward were used for analysis. If studies did not provide these data and they could not be received from the corresponding authors, only the data of completers were used. Where possible, side effects were evaluated by comparing scores on the various side effects scales, weight, body mass index, hypersalivation, and prolactin blood levels between the augmentation and the placebo group.

Statistical Analyses

Two reviewers independently extracted data from the articles, any disagreements were resolved by consensus. Effect sizes were calculated for the mean differences (placebo vs augmentation) of the change score (end of treatment minus baseline) means and SDs. Change scores were used instead of pretreatment and posttreatment scores in order to avoid overestimation of the true effect size because of the pre-post treatment correlation.48 All effect sizes were calculated twice independently from the original articles to check for errors. When more than 1 RCT on a particular augmentation strategy was present, effect sizes of studies were pooled in meta-analyses to obtain a combined weighted effect size for primary and secondary outcome measures. Hedges's g was used to quantify the mean weighted effect sizes of combined studies using a random model.49 A homogeneity statistic, I 2, was calculated to test whether the studies could be taken together to share a common population effect size.50 High heterogeneity (ie, I 2 50% or higher) indicates heterogeneity of the individual study effect sizes, which poses a limitation to a reliable interpretation of the results. Values of I 2 between 30% and 50% were considered moderate. Outliers, defined as effect sizes that deviate more than 2 SDs from the mean weighted effect size, were removed from analyses. Effect sizes with a P < .05 were considered significant. All effect sizes were computed using Comprehensive Meta Analysis Version 2.0.51

Results

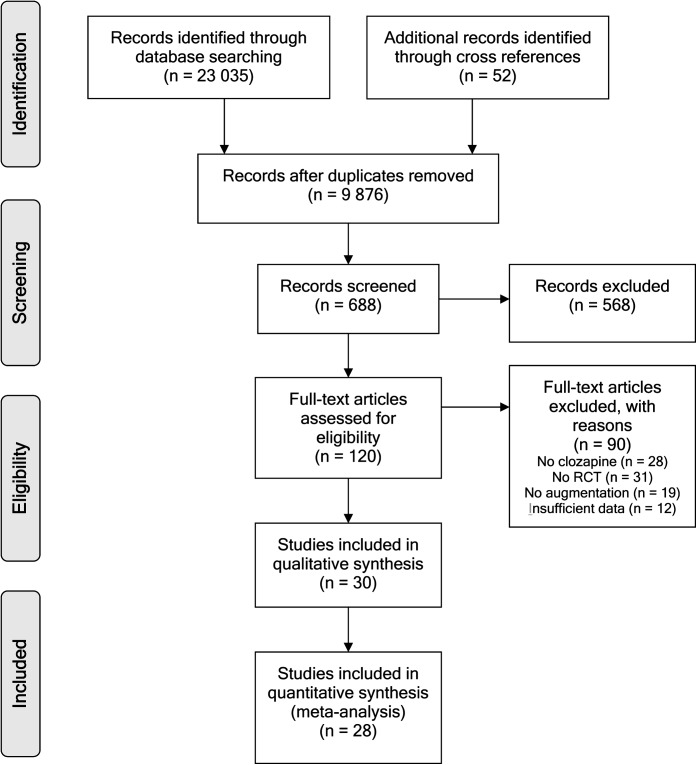

Figure 1 reflects the literature search that resulted in 29 included RCTs.18,19,23,24,29,31,52–73 Data of a total of 1066 schizophrenia and schizoaffective patients were analyzed. Of the 29 included studies, 5 studies29,52–55 had a crossover design. Double-blind RCTs that could not be included are listed in online supplementary material (table 1) with the reason for exclusion.

Fig. 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flow diagram of the literature search.

Table 1.

Summary of Augmentation Strategies and Their (Mean) Standardized Differences.

| Augmentation Strategy | Studies (N) | Subjects (N) | PANSS/BPRS Total | Positive Subscores | Negative Subscores | ||||||

| Hedges’s g | 95% CI | I 2 (%) | Hedges’s g | 95% CI | I 2 (%) | Hedges’s g | 95% CI | I 2 (%) | |||

| Antiepileptics | 7 | 189 | |||||||||

| Lamotrigine | 5 | 143 | 0.53 | 0.03–1.04 | 60 | 0.38 | −0.02 to 0.78 | 39 | 0.41 | −0.13 to 0.94 | 64 |

| Minus outlier | 4 | 92 | 0.27 | −0.10 to 0.65 | 0 | 0.15 | −0.22 to 0.52 | 0 | 0.12 | −0.25 to 0.49 | 0 |

| Topiramate | 3 | 89 | 0.75 | −0.05 to 1.56 | 69 | 0.63 | 0.03–1.23 | 47 | 0.66 | −0.17 to 1.5 | 71 |

| Minus outlier | 2 | 57 | 0.38 | −0.13 to 0.89 | 0 | 0.39 | −0.24 to 1.01 | 25 | |||

| Antidepressants | 4 | 129 | |||||||||

| Citalopram | 1 | 61 | 0.81 | 0.30–1.33 | 0.28 | −0.22 to 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.30–1.33 | |||

| Fluoxetine | 1 | 33 | No data | 0.12 | −0.55 to 0.79 | 0.19 | −0.48 to 0.86 | ||||

| Mirtazapine | 2 | 35 | 2.91 | −2.69 to 8.51 | 96 | 0.04 | −0.59 to 0.67 | 0 | 1.20 | −0.25 to 2.66 | 76 |

| Antipsychotics | 10 | 548 | |||||||||

| Amisulpride | 1 | 20 | 0.13 | −0.48 to 0.74 | 0.11 | −0.50 to 0.72 | 0.21 | −0.40 to 0.82 | |||

| Aripiprazole | 2 | 268 | 0.12 | −0.12 to 0.36 | 0 | 0.22 | −0.02 to 0.46 | 0 | 0.37 | −0.19 to 0.93 | 74 |

| Haloperidol | 1 | 6 | −0.15 | −1.51 to 1.21 | 0.26 | −1.11 to 1.62 | −0.31 | −1.68 to 1.06 | |||

| Risperidone | 5 | 226 | 0.18 | −0.21 to 0.57 | 53 | 0.09 | −0.24 to 0.74 | 56 | 0.22 | −0.14 to 0.57 | 43 |

| Sulpiride | 1 | 28 | 0.83 | 0.07–1.59 | 0.77 | 0.02–1.52 | 0.76 | 0.01–1.51 | |||

| Glutamatergics | 7 | 137 | |||||||||

| CX516 | 1 | 18 | 1.35 | 0.32–2.38 | 0.20 | −0.74 to 1.14 | 1.43 | 0.38–2.46 | |||

| D-cycloserine | 1 | 11 | No data | No data | −0.76 | −1.59 to 0.08 | |||||

| D-serine | 1 | 20 | No data | 0.40 | −0.45 to 1.24 | 0.33 | −0.52 to 1.17 | ||||

| Glycine | 3 | 68 | −0.16 | −0.62 to 0.30 | 0 | −0.36 | −1.19 to 0.46 | 67 | −0.14 | −0.60 to 0.32 | 0 |

| Sarcosine | 1 | 20 | −0.21 | −1.06 to 0.63 | −0.07 | −0.91 to 0.77 | −0.07 | −0.91 to 0.77 | |||

Note: Significant effects are indicated in bold. PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale.

Antiepileptic Medication

Eight studies applying antiepileptic drugs as clozapine augmentation were included, which are summarized in online supplementary material, for table 2.

Lamotrigine.

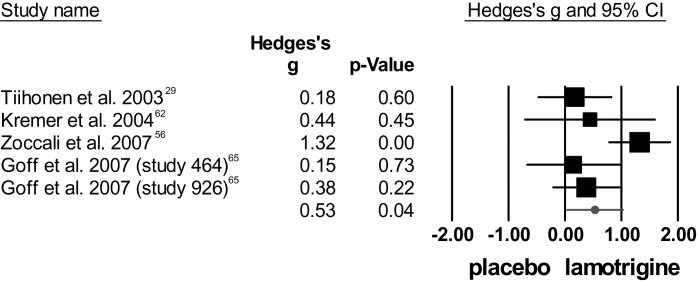

For total symptom severity, lamotrigine showed superior efficacy to placebo, but heterogeneity was high. Figure 2 plots the individual effect sizes per study regarding total symptom score from the PANSS or BPRS rating scales. The study by Zoccali et al56 was considered an outlier and therefore excluded from analysis. After exclusion, the mean weighted effect size was no longer significant and studies were homogeneous.

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis of lamotrigine augmentation for total symptom score [positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS)/brief psychiatric rating scale (BPRS)] including outlier.56

Concerning positive symptom severity, the meta-analysis showed a trend toward superiority of lamotrigine over placebo in reducing positive symptoms, and heterogeneity was moderate. Again, the study by Zoccali et al56 was an outlier. After exclusion, the trend disappeared and heterogeneity was zero.

Regarding negative symptom scores, the meta-analysis showed no significant difference between lamotrigine and placebo, and heterogeneity was high. Again, Zoccali et al56 was an outlier. After exclusion, Hedges's g decreased and heterogeneity disappeared.

Topiramate.

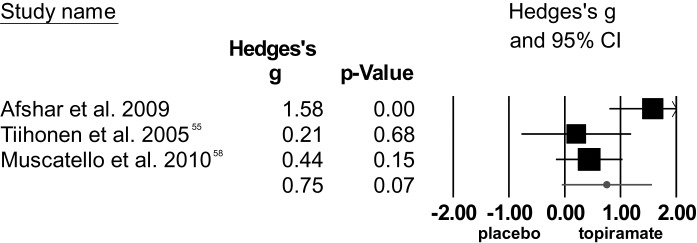

The 3 RCTs55,57,58 on topiramate as clozapine augmentation strategy, including 89 patients, showed a trend toward superior effect over placebo in reducing total symptom severity, but the data were heterogeneous. The study by Afshar et al57 was considered an outlier. After removal, the trend disappeared.

Fig. 3.

Effect sizes of studies comparing topiramate augmentation to placebo (total positive and negative syndrome scale scores) including outlier.57

Regarding positive symptoms as measured by the subscale of the PANSS, topiramate was superior to placebo, but studies were heterogeneous. The study by Afshar et al57 was considered an outlier. After exclusion, the significant effect disappeared and heterogeneity decreased. The effect of topiramate on severity of negative symptoms was not significant and studies were heterogeneous. However, the study by Afshar was not considered an outlier for this analysis. Statistical findings of these meta-analyses are summarized in table 1.

Antidepressants

Four studies concerning the efficacy of antidepressants as clozapine augmentation strategy were included. These studies are summarized in online supplementary material , table 3.

Citalopram.

One RCT59 showed significantly superior efficacy of citalopram to placebo on total symptom severity. No significant difference was found between citalopram and placebo for positive PANSS subscores. However, citalopram was found to be superior to placebo regarding negative symptoms.

Fluoxetine.

The RCT24 examining the efficacy of fluoxetine did not report PANSS total score. No significant differences were found between fluoxetine and placebo for positive symptom severity nor for negative symptoms.

Mirtazapine.

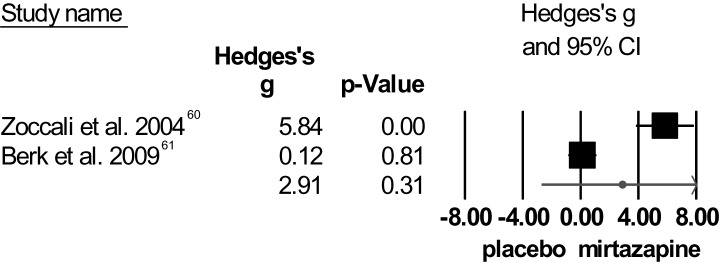

A high mean weighted effect size was obtained regarding total symptom severity for mirtazapine; yet, significance was not reached (figure 4). There was very high heterogeneity among these studies for total symptom score as well as for negative symptoms. On both measures, Zoccali et al60 showed large effect sizes, while Berk et al61 did not. Detailed inspection of the methods applied in the 2 RCTs could not identify a reason for this extreme discrepancy.

Fig. 4.

Individual effect sizes of mirtazapine augmentation for total symptom severity (positive and negative syndrome scale/brief psychiatric rating scale).

No significant difference was found between mirtazapine and placebo for PANSS-positive score nor for negative symptom score. Heterogeneity for the positive symptoms was low. Statistical findings of these meta-analyses are summarized in table 1.

Antipsychotics

We included 10 studies concerning the efficacy of antipsychotic drugs as clozapine augmentation strategy, summarized in online supplementary material, table 4.

Amisulpride.

One study62 on the efficacy of amisulpride in augmenting clozapine yielded no significant difference between amisulpride and placebo regarding total symptom severity. Amisulpride did not differ from placebo for positive symptoms nor for negative symptoms.

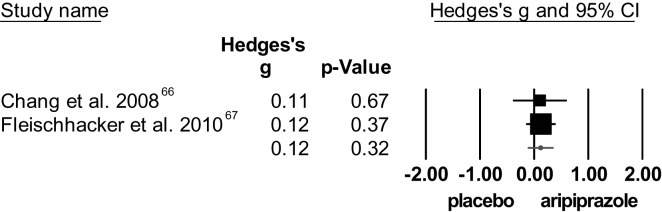

Aripiprazole.

The 2 RCTs66,67 yielded no significant difference between aripiprazole and placebo for total symptom score (see figure 5). The degree of heterogeneity was low. In addition, no significant difference was found between aripiprazole and placebo for both the PANSS-positive and -negative scores. Concerning positive symptoms, studies were homogeneous. However, the degree of heterogeneity for the negative symptoms was high.

Fig. 5.

Effect of aripiprazole on symptom severity (total positive and negative syndrome scale/brief psychiatric rating scale scores).

Haloperidol.

No significant difference was observed between haloperidol and placebo regarding change in total symptom severity. In addition, haloperidol did not differ from placebo for positive nor for negative symptoms.

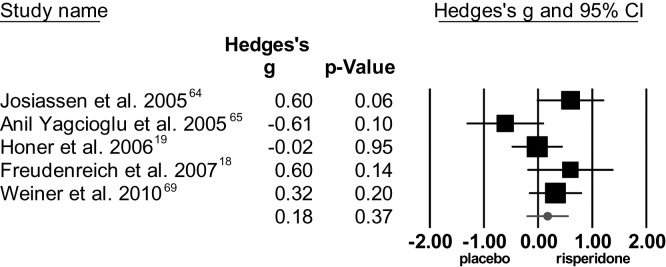

Risperidone.

The overall effect size showed no significant difference between risperidone and placebo for total symptom score, with moderate to high heterogeneity, see figure 6. For positive symptoms, the meta-analysis showed no significant difference between risperidone and placebo. Heterogeneity among studies was high. The standardized mean difference regarding negative symptoms was not significant, with moderate heterogeneity among studies.

Fig. 6.

Meta-analysis of risperidone augmentation for total symptom severity (positive and negative syndrome scale/brief psychiatric rating scale).

Sulpiride.

Sulpiride was superior to placebo in reducing total symptom severity. Regarding positive and negative symptoms, sulpiride was also superior to placebo. Statistical findings of these meta-analyses are summarized in table 1.

Glutamatergic Drugs

Seven studies concerning the efficacy of glutamatergic drugs in augmenting clozapine were included, summarized in online supplementary material, table 5.

CX516.

CX516 was superior to placebo on total symptom severity. Regarding positive symptom severity, no difference was found between CX516 and placebo. The effect on negative symptom severity was superior for CX516.

d-cycloserine.

Only the scores on the negative subscales were provided, which yielded no significant difference.

d-serine.

PANSS total scores were not provided. d-serine was not superior to placebo for positive symptoms nor for negative symptoms.

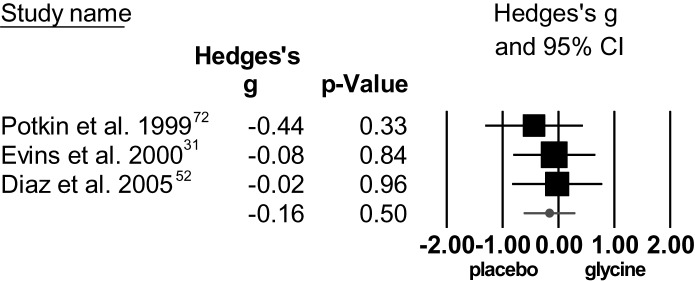

Glycine.

The standardized mean difference for total symptom severity was not significant and studies were homogeneous (figure 7). The standardized mean difference for positive symptoms was not significant, with a high degree of heterogeneity. For negative symptom severity, the standardized mean difference was not significant, with low heterogeneity.

Fig. 7.

Individual effect sizes of glycine augmentation for total symptom score (positive and negative syndrome scale/brief psychiatric rating scale).

Sarcosine.

No significant difference was observed between sarcosine and placebo regarding change in total symptom severity. Concerning positive symptoms, sarcosine did not differ from placebo, nor for negative symptoms. Statistical findings of these meta-analyses are summarized in table 1.

Side Effects

Quantitative measures of side effects are listed in the online supplementary material, table 6. These data were too diverse to perform a meta-analysis. Qualitative inspection did not show consistently higher or lower side effects in the augmentation group.

Discussion

This study aimed to systematically review all available double-blind RCTs on pharmacological additions for clozapine-resistant patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. We meta-analyzed 29 RCTs reporting on 15 different augmentation strategies that included 1066 patients in total. Better improvement of total symptom severity than placebo was found for lamotrigine, sulpiride, citalopram, and CX516 (a glutamatergic agonist). The superior efficacy of lamotrigine was only present if an outlier remained included in the meta-analysis. For sulpiride, citalopram, and CX516 results were retrieved from single RCTs. Significant better efficacy on positive symptom severity was found for topiramate and sulpiride. After outlier removal the significant effect for topiramate disappeared. Citalopram, sulpiride, and CX516 showed better efficacy for negative symptoms than placebo, all based on single studies.

Regarding clozapine augmentation with mood stabilizers, the significant effect size for lamotrigine was based on one study that deviated strongly from the others. The remaining 4 RCTs consistently showed no superior efficacy of lamotrigine than placebo. In a similar vein, the significant effect of topiramate on positive symptom severity depended on a single study with a strongly deviating finding. After exclusion of that study, topiramate was no longer superior to placebo. Thus, for both lamotrigine and topiramate, there is currently not enough evidence to regard these components as effective augmentation strategies for patients with insufficient response to clozapine. It is uncertain if this finding can be extrapolated to other mood stabilizing drugs. Small et al26 compared addition of lithium with placebo in a double-blind study and observed improvement with lithium only for schizoaffective patients but not for patients with schizophrenia.

Augmentation with antidepressants did not improve total symptom severity, except for citalopram. While citalopram caused a larger decrease in negative symptom severity than placebo, this effect was not present for fluoxetine or mirtazapine. None of the three antidepressants showed a greater improvement of positive symptoms than placebo. The addition of a second antipsychotic drug to clozapine yielded negative results, with one exception. Aripiprazole was not better than placebo in decreasing total, positive, or negative symptoms nor was risperidone. Effects of amisulpride on all measurements were comparable to placebo, while sulpiride, a substance of pharmacological similarity, showed better improvement than placebo on total symptom severity and both positive and negative subscores. A possible explanation for this difference could be the short duration of the amisulpride trial. Another RCT on amisulpride augmentation, which did not meet inclusion criteria for this study, measured effects of 6 treatment weeks but also found no improvement in total symptom severity74. Wang et al75 reviewed 3 trials adding sulpiride to clozapine, finding a subtle benefit of sulpiride over placebo. Two of the included studies were open label, and therefore not included in the current study. These open-label studies did not replicate the efficacy of sulpiride reported by Shiloh et al.23 Clearly, the positive effect of sulpiride on total, positive, and negative symptom severity needs replication before augmentation with this drug should be recommended.

When the effects of glutamatergic drugs are summarized, the general picture shows similar effects than placebo on total symptom severity and on positive and negative subscores; CX516 being the only positive exception, with superior improvement on total symptom severity and negative symptom severity. However, as glutamatergic drugs are experimental, CX516 may not be a first choice in clinical practice.

Several other authors have reviewed augmentation strategies for clozapine, the majority of them concentrated on adding a second antipsychotic drug. Taylor and Smith76 meta-analyzed augmentation of clozapine with any second antipsychotic agents. They included 10 RCTs that showed marginally superior effect compared with placebo for total symptom severity. Barbui et al77 reviewed antipsychotic addition to clozapine, which also included open-label studies. Congruent to our results, they found only modest or absent efficacy of augmentation. Kontaxakis et al78 qualitatively reviewed all studies on risperidone addition to clozapine. Their results suggested that risperidone augmentation is an effective strategy for clozapine-resistant patients. However, their positive conclusion may result from the inclusion of case reports and open case series. Tiihonen79 quantitatively summarized the effect of lamotrigine addition, including the same studies as in this review. As they did not identify Zoccali et al56 as an outlier, they arrived to a slightly more positive conclusion.

Limitations

The major limitation of this study is the relative small numbers of RCTs that could be included per drug. For some pharmacological substances, we could include single studies. This makes our database not robust against both type I and type II errors. The magnitude of the effect sizes of therapeutic interventions in mental health can change considerably with the accumulation of new data,80 and some pharmacological augmentations may yield significant effect sizes on the appearance of new RCTs, while other (perhaps sulpiride) may decrease in effect size when more studies become available. A possibility to decrease the chance for type II errors would have been to pool studies on drugs with similar pharmacological mechanisms, such as SSRIs or amino acids that stimulate the N-methyl D-aspartate receptors. In this article, we decided to present results on single drugs, as findings from pooled meta-analyses are difficult to translate into clinical practice. In addition, many vaguely acquainted agents, such as topiramate and lamotrigine, differ to such a large extent in their mechanism of action that pooling would not lead to meaningful results.

In conclusion, the general picture emerges that there is currently no replicated evidence for any pharmacological augmentation strategy to combat resistant total, positive, or negative symptoms in clozapine-treated patients. All positive effects were either based on one outlying study or derived from a single RCT.

Funding

De Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NWO)/ZonMW (Dutch Scientific Research Organization) Clinical Fellowship 2009 (4000703-97-270) and NWO/ZonMW (Dutch Scientific Research Organization) Innovation Impulse (Vidi) 2009 (017.106.301) to Dr Sommer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Zhida Xu for extracting the correct data from the Chinese publications. In addition, we would like to thank the contacted authors for their time and energy to provide additional data to enable this meta-analysis. The authors Iris Sommer, Marieke Begemann, and Anke Temmerman have no conflicts of interest relating to this article. Stefan Leucht received speaker/consultancy/advisory board honoraria from SanofiAventis, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Actelion, EliLilly, Essex Pharma, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen/Johnson and Johnson, Lundbeck and Pfizer. SanofiAventis and EliLilly supported research projects by Stefan Leucht.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org.

References

- 1.Conley RR, Buchanan RW. Evaluation of treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23:663–674. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.4.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGlashan TH. A selective review of recent North American long-term followup studies of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1988;14:515–542. doi: 10.1093/schbul/14.4.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Revicki DA, Luce BR, Weschler JM, Brown RE, Adler MA. Economic grand rounds: cost-effectiveness of clozapine for treatment-resistant schizophrenic patients. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1990;41:850–854. doi: 10.1176/ps.41.8.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies LM, Drummond MF. Economics and schizophrenia: the real cost. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1994;25:18–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H. Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic. A double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;5:789–796. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800330013001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chakos M, Lieberman J, Hoffman E, Bradford D, Sheitman B. Effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotics in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:518–526. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis SW, Barnes TRE, Davies L, et al. Randomized controlled trial of effect of prescription of clozapine versus other second-generation antipsychotic drugs in resistant schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:715–723. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, et al. Effectiveness of clozapine versus olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia who did not respond to prior atypical antipsychotic treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:600–610. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulte PFJ. What is an adequate trial with clozapine? Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:607–618. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342070-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ, Pollack S, et al. Clinical effects of clozapine in chronic schizophrenia: response to treatment and predictors of outcome. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1744–1752. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.12.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meltzer HY, Bastani B, Kwon KY, Ramirez LF, Burnett S, Sharpe J. A prospective study of clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenic patients: i: Preliminary report. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1989;99:S68–S72. doi: 10.1007/BF00442563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tollefson GD, Birkett MA, Kiesler GM, Wood AJ. Lilly Resistant Schizophrenia Study Group. Double-blind comparison of olanzapine versus clozapine in schizophrenic patients eligible for treatment with clozapine. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:59–60. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickerson FB. Cognitive behavioural psychotherapy for schizophrenia: a review of recent empirical studies. Schizophr Res. 2000;43:71–90. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00153-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buckley P, Miller A, Olsen J, Garver D, Miller DD, Csernansky J. When symptoms persist: clozapine augmentation strategies. Schizophr Bull. 2001;27:615–628. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slotema CW, Blom JD, Hoek HW, Sommer IE. Should we expand the toolbox of psychiatric treatment methods to include Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS)? A meta-analysis of the efficacy of rTMS in psychiatric disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:873–884. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04872gre. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Havaki-Kontaxaki BJ, Ferentinos PP, Kontaxakis VP, Paplos KG, Soldatos CR. Concurrent administration of clozapine and electroconvulsive therapy in clozapine-resistant schizophrenia. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2006;29:52–56. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200601000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis JM. The choice of drugs for schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:518–520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freudenreich O, Henderson DC, Walsh JP, Culhane MA, Goff DC. Risperidone augmentation for schizophrenia partially responsive to clozapine: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Schizophr Res. 2007;92:90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honer WG, Thornton AE, Chen EY, et al. Clozapine alone versus clozapine and risperidone with refractory schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:472–482. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paton C, Whittington C, Barnes TR. Augmentation with a second antipsychotic in patients with schizophrenia who partially respond to clozapine: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27:198–204. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318036bfbb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrato EH, Dodd S, Oderda G, Haxby DG, Allen R, Valuck RJ. Prevalence, utilization patterns, and predictors of antipsychotic polypharmacy: experience in a multistate Medicaid population, 1998-2003. Clin Ther. 2007;29:183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henderson DC, Goff DC. Risperidone as an adjunct to clozapine therapy in chronic schizophrenics. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57:395–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shiloh R, Zemishlany Z, Aizenberg D, et al. Sulpiride augmentation in people with schizophrenia partially responsive to clozapine. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:569–573. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.6.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buchanan RW, Kirkpatrick B, Bryant N, Ball P, Breier A. Fluoxetine augmentation of clozapine treatment in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1625–1627. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.12.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silver H, Kushnir M, Kaplan A. Fluvoxamine augmentation in clozapine-resistant schizophrenia: an open pilot study. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40:671–674. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(96)00170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Small JG, Klapper MH, Malloy FW, Steadman TM. Tolerability and efficacy of clozapine combined with lithium in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23:223–228. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000084026.22282.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kando JC, Tohen M, Castillo J, Centorrino F. Concurrent use of clozapine and valproate in affective and psychotic disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55:255–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simhandl C, Meszaros K. The use of carbamazepine in the treatment of schizophrenic and schizoaffective psychosis: a review. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1992;17:1–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tiihonen J, Hallikainen T, Ryynanen OP, et al. Lamotrigine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a randomized placebo-controlled crossover trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:1241–1248. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00524-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Semaan Y. Bromocriptine as adjunctive therapy to clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 1996;41:484–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evins AE, Fitzgerald SM, Wine L, Rosselli R, Goff DC. Placebo-controlled trial of glycine added to clozapine in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:826–828. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carpenter WT, Breier A, Buchanan RW, Kirkpatrick B, Shepard P, Weiner E. Mazindol treatment of negative symptoms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:365–374. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peet M, Horrobin DF. E-E Multicentre Study Group. A dose-ranging exploratory study of the effects of ethyl-eicosapentaenoate in patients with persistent schizophrenic symptoms. J Psychiatr Res. 2002;36:7–18. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(01)00048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chong SA, Remington G. Clozapine augmentation: safety and efficacy. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:421–440. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lerner V, Libov I, Kotler M, Strous RD. Combination of ‘atypical’ antipsychotic medication in the management of treatment-resistant schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams L, Newton G, Roberts K, Finlayson S, Brabbins C. Clozapine-resistant schizophrenia: a positive approach. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:184–187. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.3.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crawford JM, Briggs CL, Engeland CG. Publication bias and its implications for evidence-based clinical decision making. J Dent Educ. 2010;74:593–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Remington G, Saha A, Chong S, Shammi C. Augmentation strategies in clozapine-resistant schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2005;19:843–872. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200519100-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frances A, Docherty JP, Kahn DA. The expert consensus guideline series: treatment of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57:1–50. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, Noel JM, Boggs DL, Fischer BA. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2009;36:71–93. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Organisation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical Meta-Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Overall JE, Gorham DR. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10:790–812. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SANS) Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dunlap WP, Cortina JM, Vaslow JB, Burke MJ. Meta-analysis of experiments with matched groups or repeated measures designs. Psychol Methods. 1996;1:170–177. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shadish WR, Haddock CK. Combining estimates of effect size. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, editors. The Handbook of Research Synthesis. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1994. pp. 261–281. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H. Comprehensive Meta Analysis Version 2. Engelwood, NJ: Biostat Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Diaz P, Bhaskara S, Dursun SM, Deakin B. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial of clozapine plus glycine in refractory schizophrenia negative results. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25:277–278. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000165740.22377.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goff DC, Henderson DC, Evins AE, Amico E. A placebo-controlled crossover trial of D-cycloserine added to clozapine in patients with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:512–514. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kreinin A, Novitski D, Weizman A. Amisulpride treatment of clozapine-induced hypersalivation in schizophrenia patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;21:99–103. doi: 10.1097/01.yic.0000188216.92408.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tiihonen J, Halonen P, Wahlbeck K. Topiramate add-on in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1012–1015. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zoccali R, Muscatello MR, Bruno A, et al. The effect of lamotrigine augmentation of clozapine in a sample of treatment-resistant schizophrenic patients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2007;93:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Afshar H, Roohafza H, Mousavi G, et al. Topiramate add-on treatment in schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23:157–162. doi: 10.1177/0269881108089816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Muscatello MRA, Bruno A, Pandolfo G. Topiramate augmentation of clozapine in schizophrenia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Psychopharmacol. doi: 10.1177/0269881110372548. July 8, 2010; doi:10.117/0269881110372548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lan GX, Li ZC, Li L. A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of combined citalopram and clozapine in the treatment of negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Chin Ment Health J. 2006;20:696–698. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zoccali R, Muscatello MR, Cedro C, et al. The effect of mirtazapine augmentation of clozapine in the treatment of negative symptoms of schizophrenia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;19:71–76. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200403000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Berk M, Gama CS, Sundram S, et al. Mirtazapine add-on therapy in the treatment of schizophrenia with atypical antipsychotics: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2009;24:233–238. doi: 10.1002/hup.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kremer I, Vass A, Gorelik I, et al. Placebo- controlled trial of lamotrigine added to conventional and atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:441–446. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anil Yagcioglu AE, Kiviricik Akdede BB, Turgut TI, et al. A Double-Blind Controlled Study of Adjunctive Treatment With Risperidone in Schizophrenic Patients Partially Responsive to Clozapine: efficacy and Safety. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:63–72. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Josiassen RC, Joseph A, Kohegyi E, et al. A Clozapine Augmented With Risperidone in the Treatment of Schizophrenia: a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:130–136. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goff DC, Keefe R, Citrome L, et al. Lamotrigine as add-on therapy in schizophrenia: results of 2 placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27:582–589. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e31815abf34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chang JS, Ahn YM, Park HJ, et al. Aripiprazole augmentation in clozapine-treated patients with refractory schizophrenia: An 8-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(5):720–731. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fleischhacker WW, Heikkinen ME, Olié JP, et al. Effects of adjunctive treatment with aripiprazole on body weight and clinical efficacy in schizophrenia patients treated with clozapine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13(8):1115–1125. doi: 10.1017/S1461145710000490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mossaheb N, Sacher J, Wiesegger G, et al. Haloperidol in combination with clozapine in treatment-refractory patients with schizophrenia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;16(suppl. 4):416. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weiner E, Conley RR, Ball MP, et al. July 21, 2010. Adjunctive risperidone for partially responsive people with schizophrenia treated with clozapine. Neuropsychopharmacol. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.101. doi:10.1038/npp.2010.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Goff DC, Leahy L, Berman I, et al. A placebo-controlled pilot study of the ampakine CX516 added to clozapine in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21:484–487. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200110000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tsai GE, Yang P, Chung LC, Tsai IC, Tsai CW, Coyle JT. D-serine added to clozapine for the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1822–1825. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.11.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Potkin SG, Jin Y, Bunney BG, Costa J, Gulasekaram B. Effect of clozapine and adjunctive high-dose glycine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:145–147. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lane HY, Huang CL, Wu PL, et al. Glycine transporter I inhibitor, N-methylglycine (sarcosine), added to clozapine for the treatment of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:645–649. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Assion HJ, Reinbold H, Lemanski S, Basilowski M, Juckel G. Amisulpride augmentation in patients with schizophrenia partially responsive or unresponsive to clozapine. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2008;41:24–28. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-993209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang J, Omori IM, Fenton M, Soares B. Sulpiride augmentation for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:229–230. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Taylor DM, Smith L. Augmentation of clozapine with a second antipsychotic—a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119:419–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Barbui C, Signoretti A, Mulè S, Boso M, Cipriani A. Does the addition of a second antipsychotic drug improve clozapine treatment? Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:458–468. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kontaxakis VP, Ferentinos PP, Havaki-Kontaxaki BJ, Paplos KG, Pappa DA, Christodoulou GN. Risperidone augmentation of clozapine: a critical review. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256:350–355. doi: 10.1007/s00406-006-0643-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tiihonen J, Wahlbeck K, Kiviniemi V. The efficacy of lamotrigine in clozapine-resistant schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2009;109:10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Trikalinos TA, Churchill R, Ferri M, et al. EU-PSI project. Effect sizes in cumulative meta-analyses of mental health randomized trials evolved over time. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:1124–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.