Abstract

Purpose of review

Preeclampsia remains a major health concern in the United States and worldwide. Recent research has begun to shed light on the underlying mechanisms responsible for the symptoms of preeclampsia, and may provide new avenues for therapy for the preeclamptic patient.

Recent findings

The central role of placental ischemia in the manifestation of preeclampsia has provided new understanding for the origin of pathogenic factors in the preeclamptic patient. The release of soluble factors into the maternal blood stream from the ischemic placenta is now recognized as a central mechanism in disease manifestation. Specifically, the importance of the vascular endothelial growth factor antagonist soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase and immune factors as factors regulating maternal endothelial dysfunction has become widely acknowledged. Furthermore, mounting evidence implicates the signaling protein endothelin-1 as the final converging factor in the multifaceted cascades that are responsible for the symptomatic manifestation of preeclampsia. Endothelin-1, as a final common pathway in the pathogenic cascade of preeclampsia presents an intriguing new therapeutic approach for preeclamptic patients.

Summary

Identification of antiangiogenic, autoimmune, and inflammatory factors produced in response to placental ischemia have provided potential new avenues for future research into novel therapies for the preeclamptic patient, and suggest new therapeutic avenues for the treatment of preeclampsia.

Keywords: angiotensin type 1 receptor agonistic autoantibody, placental ischemia, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1, tumor necrosis factor-α, vascular endothelial growth factor

INTRODUCTION

Despite increased awareness and more aggressive management, preeclampsia remains a major health concern, affecting approximately 8% of all pregnancies in the nation and is a major risk factor for perinatal mortality [1]. Classically, preeclampsia has been defined by new-onset hypertension, proteinuria, and edema. Edema, however, is no longer considered a necessary finding for diagnosis. Further, recent discussion has questioned whether the measurement of absolute proteinuria is truly diagnostic, or whether other measures of renal function should be included in future guidelines [2▪].

Previous incidence of preeclampsia, high prepregnancy BMI, underlying medical conditions, primiparity, ethnicity, and smoking are recognized maternal risk factors for preeclampsia [3▪,4▪]. A systematic review in risk factors for preeclampsia reported an approximately seven-fold increased risk of preeclampsia in women who had previously exhibited the disorder compared with women with no history of preeclampsia [5]. In addition, several studies have shown that high BMI before pregnancy more than doubles preeclampsia risk and that the degree of obesity directly correlates with the increased risk of developing preeclampsia [5,6▪▪]. Recent studies have suggested that the functional link between maternal obesity and preeclampsia might be through mechanisms involving oxidative stress, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction [7]. The prevalence of underlying medical conditions such as preexisting high blood pressure (BP) (approximately two-fold for systolic ≥130 mmHg), preexisting diabetes (approximately four-fold), and antiphospholipid syndrome (approximately 10-fold), is elevated in women who develop preeclampsia compared with women who did not [5]. Preeclampsia is three times more likely to develop in primiparous compared with multiparous women [5], possibly due to a decrease in circulating soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1) from first to second pregnancy [8]. There also appears to be a disparity in incidence in ethnic subgroups, as among primiparous women, the risk of preeclampsia is doubled in black mothers compared with white mothers [9]. Supporting this, there is also an increased risk in women of Indian and Pakistani origin [3▪]. These observed differences between ethnic subgroups strongly suggest that genetic components play a role in the risk of developing preeclampsia.

Multiple gestation is a well established risk factor for the development of preeclampsia [4▪]. The incidence of preeclampsia in twin pregnancies is approximately three-fold higher than that seen in single pregnancies [5], probably due to an increased release of sFlt-1 into the maternal circulation by the greater placental mass-associated twins [10]. Some risk factors for preeclampsia that currently lack clear mechanistic links are maternal age, previous miscarriages, induced abortions, interpregnancy interval, primipaternity, familial aggregation, and environmental factors, such as exercise, infections, seasonal variation, and socioeconomic factors [4▪].

Although a number of risk factors have been implicated in preeclampsia, their exact role in the pathophysiology of this disease remains unclear. In this brief review, we have sought to highlight some of the recent work that has begun to shed light on the molecular mechanisms of preeclampsia, and which present new potential research and therapeutic opportunities. In particular, we will highlight recent work looking at the role of antiangiogenic and inflammatory factors produced in response to placental ischemia and demonstrate their link to maternal endothelial dysfunction. We also emphasize research that suggests a final common pathway in the symptomatic manifestations of preeclampsia, the endothelin-1 system.

ROLE OF PLACENTAL ISCHEMIA IN THE PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF PREECLAMPSIA

Although the underlying mechanisms which initiate preeclampsia are not clear, it is known that the symptomatic phase of the disease originates with the placenta, as delivery of the fetus alone is not palliative, and only removal of the entire placenta will cause the condition to remit [11,12]. Once common finding is a failure to adequately remodel the maternal vasculature during placental development to allow adequate oxygenation of the uteroplacental unit [13]. This, in turn, results in chronic placental ischemia and hypoxia and leads to the release of soluble factors into the maternal bloodstream, which act as pathological agents. Recent work has implicated a number of pathways that link the ischemic placenta to the maternal symptomatic phase of the disorder. In particular, the release of the antiangiogenic factor sFlt-1, and the induction of the maternal innate and adaptive immune responses.

ALTERED ANGIOGENIC BALANCE IN PREECLAMPSIA

Perhaps the most intriguing avenue of research to emerge in the study of preeclampsia in recent years is the link between placental ischemia and the soluble vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor sFlt-1. sFlt-1 is an alternatively spliced form of the VEGF receptor Flt-1 which lacks the anchoring transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains, making it soluble. When secreted extracellularly, it acts as a decoy receptor, binding VEGF and making it unavailable for normal signaling activity. This is likely to be a major source of the maternal endothelial dysfunction as VEGF signaling is important for the maintenance and propagation of endothelial cells [14▪▪]. During pregnancy, sFlt-1 and VEGF are both produced in abundance from the placenta, and one of the seminal findings in preeclampsia research has been that sFlt-1 is elevated significantly in response to placental ischemia. This leads to a relative increase in the levels of sFlt-1 in the maternal circulation, which may in fact precede the symptomatic phase of the disorder [15].

A number of experimental observations have supported the pathogenic role of sFlt-1 in the symptomatic manifestation of preeclampsia. Pregnant rodents that are administered exogenous sFlt-1 directly or through retroviral delivery exhibit hypertension and proteinuria that are characteristics of the preeclamptic patient [16,17]. Interestingly, similar observations have been made in human trials of the VEGF antibody bevacizumab, an adjunct therapy for certain cancers, which presumably operates mechanistically in a manner similar to sFlt-1 [18]. Most intriguingly, several studies have suggested that inhibition of sFlt-1 by decoy-binding peptides can attenuate many the symptoms of preeclampsia in animal models [19▪▪,20]. Most recently, a small pilot study demonstrated that removal of sFlt-1 by aphoresis could improve BP and proteinuria in patients suffering from early-onset preeclampsia [21▪]. Taken together, these data suggest that sFlt-1 is a major component of the maternal symptoms shown during preeclampsia, and that targeting sFlt-1 in preeclamptic patients may be a useful strategy for the treatment of the disorder.

THE MATERNAL IMMUNE RESPONSE

One other major pathway that has been implicated in the progression from placental ischemia to the maternal symptoms of preeclampsia is the activation of the maternal innate and adaptive to immune response. During pregnancy the maternal inflammatory response is heightened even under normal conditions. In the preeclamptic patient, however, the activation of the innate immune response is heightened, which results in elevated circulating levels of inflammatory cytokines. Specifically, the cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 are significantly elevated in preeclamptic patients [22,23]. TNF-α has been shown to be elevated in response to placental ischemia in a rodent model. Interestingly, administration of the soluble TNF-α receptor etanercept significantly blunted the hypertension that is characteristic of this model, pointing to the importance of TNF-α in the path from placental ischemia to hypertension [24]. These studies have recently been confirmed in the baboon, as infusion of TNF-α to pregnant dams resulted in hypertension and proteinuria. This study also demonstrated that TNF-α in a nonhuman primate model induced the expression of sFlt-1, hinting at a role for inflammation in the overexpression of sFlt-1 during preeclampsia [25▪]. This is not the only study suggesting a functional link between sFlt-1 and TNF-α, as a recent study has shown that TNF-α dependent endothelial cell activation can be significantly enhanced by preincubations with sFlt-1 [26▪]. Further work elucidating the role of TNF-α in pregnancy and its interaction with sFlt-1 should prove elucidating.

In addition to the innate immune response, there is growing evidence for a role of the adaptive immune response in the development of preeclampsia. One factor that has received a lot of attention in recent studies is the angiotensin type 1 receptor agonistic autoantibody (AT1-AA), which has been identified in the circulation of patients diagnosed with preeclampsia [27]. This antibody has been shown to induce nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase activity in vitro, increasing oxidative stress, another potential mediator of endothelial dysfunction [28]. The AT1-AA has also been shown to be produced in experimental animal models of placental ischemia and TNF-α infusion. Interestingly, blockade of the AT1 receptor in both models resulted in a significant decrease in mean arterial pressure [29]. Intriguingly, there also appears to be a role for AT1-AA in the regulation of sFlt-1, as the AT1-AA appears to directly upregulate sFlt-1 production through the AT1 receptor [30]. One particularly interesting study has demonstrated that blockade of the AT1-AA by a synthetic decoy peptide corresponding to the antibody’s epitope can completely negate the hypertension induced by the antibody. This suggests an interesting potential therapy for the treatment of preeclamptic women [31].

ENDOTHELIN-1: A CENTRAL FACTOR IN PREECLAMPSIA?

There is growing evidence to suggest an important role for endothelin-1 in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. Endothelin-1 is one of the most powerful vasoconstrictors produced by the human body. Multiple studies have examined circulating levels of endothelin-1 in normal pregnant and preeclamptic women, and found elevated levels of plasma endothelin-1 in the preeclamptic group, with some studies indicating that the level of circulating endothelin-1 correlates with the severity of the disease symptoms, although this is not a universal finding [32–34]. As endothelin-1 mainly serves as a paracrine or autocrine factor and plasma levels of endothelin-1 do not necessarily reflect local tissue production, the role of endothelin-1 in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia has been underestimated.

In recent years, several excellent animal models of experimental preeclampsia have been developed to obtain a better understanding of the pathophysiology of preeclampsia and to better establish cause and effect relationships of factors that have been postulated to be involve in human preeclampsia. One model that has proven to mimic many of the hallmarks of preeclampsia is the reduced uterine perfusion pressure (RUPP) model. In this model, blood flow to the uterus is partially occluded during the later stages of gestation, resulting in severe placental hypoxia and ischemia. This model has been recapitulated in rodent, canine, and nonhuman primates, with hypertension, elevated sFlt-1, endothelial dysfunction, renal injury, and resulting proteinuria being common findings [35–37]. Initial findings in the rodent RUPP model demonstrated that cortical concentrations of preproendothelin mRNA were significantly elevated when compared with healthy pregnant controls, as assayed by RNAse protection assays. Moreover, although administration of an endothelin type A receptor (ETA) specific antagonist had no effect on normal pregnant animals, in the RUPP treated animals, the associated hypertension was completely normalized by ETA antagonism [38]. Follow-up studies utilizing human umbilical vein endothelial cells and sera from RUPP treated rats demonstrated that ET-1 release was stimulated by RUPP serum when compared with serum obtained from normal pregnant rats [39]. It is clear then that the hypertension seen in the RUPP placental ischemia model is heavily dependent on increased ET-1 production and signaling through the ETA receptor.

As previously mentioned, a number of clinical and experimental studies have supported an important role of sFlt-1 in the symptomatic manifestation of preeclampsia. Thus, another important animal model that has been established is the sFlt-1 excess model in which animals that are administered exogenous sFlt-1 directly or through retroviral delivery exhibit hypertension, proteinuria, and other characteristics of the preeclampsia [16,17, 40▪]. A recent study demonstrated that the administration of sFlt-1 to pregnant rats also significantly increases BP and the production of preproendothelin message levels in the renal cortex. With co-administration of an ETA antagonist, however, this hypertensive response was completely abolished, suggesting a critical role for ET-1 in sFlt-1-induced hypertension [40▪]. Thus, the hypertension produced by sFlt-1 excess appears to be dependent on activation of the endothelin system.

There also appears to be an important interaction between endothelin-1 and immune factors such as inflammatory cytokines and AT1-AA. In response to TNF-α infusion, pregnant rats demonstrate an approximately 20 mmHg increase in mean arterial pressure and a concomitant increase in the expression of preproendothelin expression in the aorta, placenta, and renal tissue from TNF-α-infused rats. Moreover, administration of an ETA specific antagonist completely abolished the hypertension in response to TNF-α. Interestingly, administration of the soluble TNF-α receptor etanercept resulted in the partial abrogation of RUPP-induced hypertension and reduced tissue expression of preproendothelin, suggesting that ET-1 expression is at least partially driven by increases in TNF-α [24]. Thus, it appears that endothelin signaling plays an important role in the symptomatic consequences of this pathway.

Further evidence for an important interaction between immune factors and endothelin-1 is the findings that infusion of the purified AT1-AA into pregnant rats resulted in an approximate 20% increase in the mean arterial pressure. Analysis of tissue expression of preproendothelin levels showed a dramatic increase in expression, showing that AT1 receptor activation by AT1-AA could play a critical role in ET-1 production during preeclampsia. Again, pharmacologic blockade of the ETA receptor completely abolished the hypertensive response to AT1-AA infusion, demonstrating yet again that endothelin-1 is a central agent in the disease of hypertension in response to placental ischemia [41].

SUMMARY

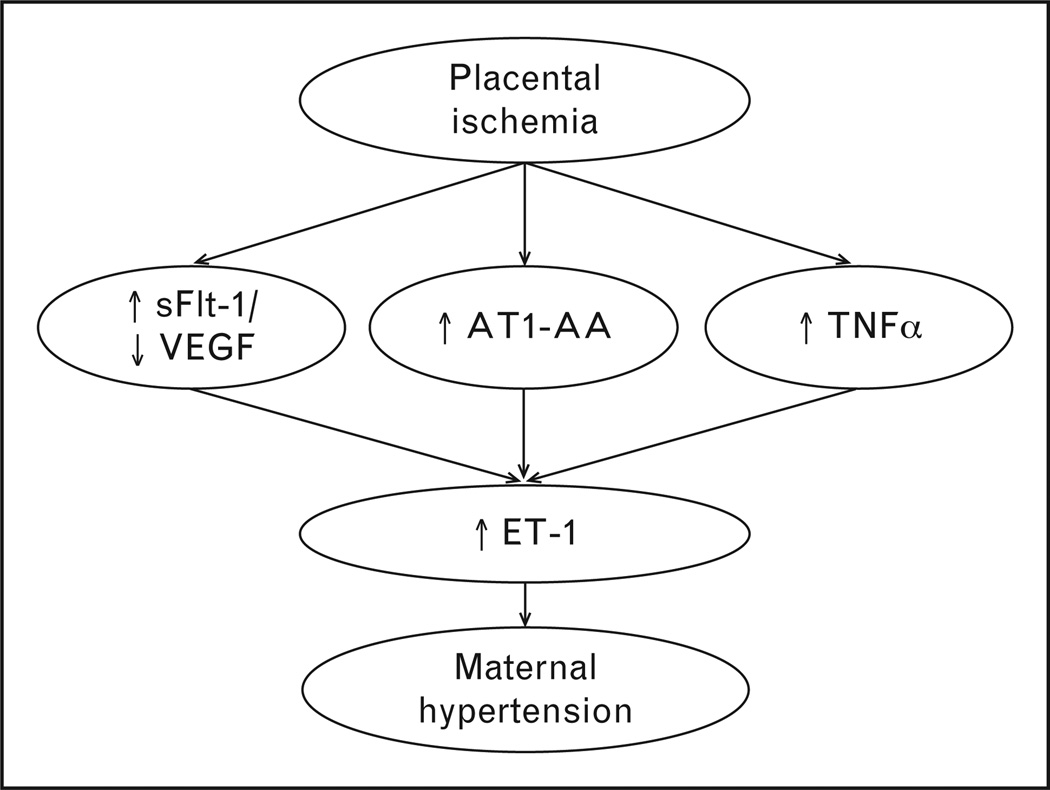

The release of soluble factors into the maternal blood stream from the ischemic placenta is now recognized as a key event in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Specifically, the importance of the VEGF antagonist sFlt-1 and immune factors as factors regulating maternal endothelial dysfunction has become widely acknowledged. There is also growing evidence to suggest that endothelin-1 may be a final common pathway that links these soluble factors in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. As seen in Fig. 1, multiple mechanisms, all mediated by placental ischemia, induce ET-1 expression. Experimentally, ETA receptor antagonism abolishes the hypertension produced by each of these mediators. Is this then a potential target for therapeutic intervention? A great deal of anxiety has surrounded ETA blockade during pregnancy because of the fact that ETA receptor deletion in mice has proven to cause birth defects and embryonic lethality [42], and subsequently the administration of endothelin receptor antagonists is contraindicated during pregnancy. However, succeeding studies have demonstrated that there are specific temporal windows during gestation in which pharmacological blockade of the receptor mimics the effects of the constitutive knockout. ETA blockade during midgestation was implicated as the pivotal window for the previously characterized birth defects, as administration of the antagonist before and after midgestation resulted in differential effects [43]. Other studies have demonstrated that administration of a selective ETA antagonist only in late gestation has no teratogenic effect in either mice or rats [44,45]. The possibility remains that ETA receptor antagonists might be successfully administered in late gestation to control the most severe symptoms of preeclampsia. Further, it is not known whether all of the available specific ETA receptor antagonists cross the placental barrier. It is possible that one of the existing antagonists may prove well tolerated by being unable to cross the placenta into the developing fetus. Alternatively, development of new antagonists which do not cross the placental barrier may provide a new therapeutic approach. Continued research into the safety and efficacy of ETA receptor blockade during pregnancy and preeclampsia is warranted, and may provide an effective target for this complicated and difficult to treat disorder.

FIGURE 1.

Placental ischemia is a central causative agent in the development of preeclampsia. In response to chronic hypoxia/ischemia, multiple pathogenic agents are released into the maternal circulation. Among the most prominent is the antiangiogenic protein soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1), which decreases free VEGF in the maternal circulation. Also inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and agonistic antibodies to the angiotensin type 1 receptor (AT1-AA). Each of these factors has been shown experimentally to act through the activation of the endothelin-1 (ET-1) system, leading to maternal hypertension, and indicating that the ET-1 system might be a logical target for the management of hypertension in the preeclamptic patient.

CONCLUSION

Recent research has begun to elucidate the link between placental ischemia and hypertension in the preeclamptic patient. Although there are numerous pathways involved, including altered angiogenic factor balance and the maternal immune response, a common end pathways appears to be the endothelin-1 system. Therapies directly increasing uteroplacental perfusion to reduce the placental ischemia, or targeting of the endothelin-1 system are intriguing new potential interventions in the management of the preeclamptic patient.

KEY POINTS.

Placental ischemia is a common central agent in the development of preeclampsia.

In response to chronic ischemia in the placenta, the levels of circulating antiangiogenic factors is increased, which have been shown to be important agents in the development of maternal hypertension.

The maternal innate and adaptive immune responses are also induced by placental ischemia, which contribute significantly to the maternal symptoms.

The endothelin-1 system is a common final pathway by which the antiangiogenic factors and autoimmune response lead to maternal hypertension.

Future therapies targeting increased placental perfusion, or the endothelin-1 system directly, may provide new interventions for the preeclamptic patient.

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of interest

This work was supported by NIH grants HL108618-01, HL105324–01, HL51971, 1T32HL105324–01, and a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association (11POST7840039).

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

Additional references related to this topic can also be found in the Current World Literature section in this issue (pp. 000–000).

- 1.Roberts JM, Pearson G, Cutler J, Lindheimer M. Summary of the NHLBI Working Group on research on hypertension during pregnancy. Hypertension. 2003;41:437–445. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000054981.03589.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lindheimer MD, Kanter D. Interpreting abnormal proteinuria in pregnancy: the need for a more pathophysiological approach. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 Pt 1):365–375. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cb9644. This article highlights the limitations of proteinuria as a diagnostic in the preeclamptic patient, and highlights the need for new criteria to assess renal function in these patients.

- 3. Poon LC, Kametas NA, Chelemen T, et al. Maternal risk factors for hypertensive disorders in pregnancy: a multivariate approach. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:104–110. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2009.45. This study performs statistical analysis of a host of risk factors for preeclampsia to assemble a predictive model for preeclampsia screening.

- 4. Trogstad L, Magnus P, Stoltenberg C. Preeclampsia: risk factors and causal models. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;25:329–342. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2011.01.007. This article reviews the current literature and thoroughly examines the current evidence for statistically significant risk factors for the development of preeclampsia.

- 5.Duckitt K, Harrington D. Risk factors for preeclampsia at antenatal booking: systematic review of controlled studies. BMJ. 2005;330:565. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38380.674340.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gaillard R, Steegers EA, Hofman A, Jaddoe VW. Associations of maternal obesity with blood pressure and the risks of gestational hypertensive disorders. The Generation R Study. J Hypertens. 2011;29:937–944. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328345500c. This study examined the correlation between maternal obesity and the risk of developing preeclampsia and gestational hypertension in a large cohort. Significant effects of high BMI were found for both disorders, highlighting the importance of maternal adiposity in the development of preeclampsia and gestational hypertension.

- 7.Walsh SW. Obesity: a risk factor for preeclampsia. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2007;18:365–370. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolf M, Shah A, Lam C, et al. Circulating levels of the antiangiogenic marker sFLT-1 are increased in first versus second pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knuist M, Bonsel GJ, Zondervan HA, Treffers PE. Risk factors for preeclampsia in nulliparous women in distinct ethnic groups: a prospective cohort study. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:174–178. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bdolah Y, Lam C, Rajakumar A, et al. Twin pregnancy and the risk of preeclampsia: bigger placenta or relative ischemia? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:428e1–428e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.10.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shembrey MA, Noble AD. An instructive case of abdominal pregnancy. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;35:220–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1995.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hladunewich M, Karumanchi SA, Lafayette R. Pathophysiology of the clinical manifestations of preeclampsia. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:543–549. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03761106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brosens IA, Robertson WB, Dixon HG. The role of the spiral arteries in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol Annu. 1972;1:177–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wu FT, Stefanini MO, Mac Gabhann F, et al. A systems biology perspective on sVEGFR1: its biological function, pathogenic role and therapeutic use. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:528–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00941.x. This study exhaustively examines the available literature concerning the molecular mechanisms of sFlt-1 and makes a strong case for its importance in several disease states, including preeclampsia.

- 15.Levine RJ, Lam C, Qian C, et al. Soluble endoglin and other circulating antiangiogenic factors in preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:992–1005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J, et al. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:649–658. doi: 10.1172/JCI17189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bridges JP, Gilbert JS, Colson D, et al. Oxidative stress contributes to soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 induced vascular dysfunction in pregnant rats. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:564–568. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang JC, Haworth L, Sherry RM, et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab, an antivascular endothelial growth factor antibody, for metastatic renal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:427–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gilbert JS, Verzwyvelt J, Colson D, et al. Recombinant vascular endothelial growth factor 121 infusion lowers blood pressure and improves renal function in rats with placentalischemia-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2010;55:380–385. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.141937. This study demonstrated that restoration of circulating free VEGF levels in rodents significantly improved renal function and hypertension in rats with placental ischemia. This highlights the importance of sFlt-1 in the disorder of placental ischemia, and suggests that restoration of VEGF might be a potential therapeutic in preeclampsia.

- 20.Bergmann A, Ahmad S, Cudmore M, et al. Reduction of circulating soluble Flt-1 alleviates preeclampsia-like symptoms in a mouse model. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:1857–1867. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00820.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thadhani R, Kisner T, Hagmann H, et al. Pilot study of extracorporeal removal of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 in preeclampsia. Circulation. 2011;124:940–950. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.034793. In this promising pilot study, Thadhani et al. removed circulating sFlt-1 from preeclamptic women by apheresis, resulting in improvements in hypertension, proteinuria, and time to delivery. This is the first study of sFlt-1 neutralization in humans and is a potentially powerful approach for the management of severe preeclampsia.

- 22.Conrad KP, Miles TM, Benyo DF. Circulating levels of immunoreactive cytokines in women with preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1998;40:102–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1998.tb00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greer IA, Lyall F, Perera T, et al. Increased concentrations of cytokines interleukin-6 and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in plasma of women with preeclampsia: a mechanism for endothelial dysfunction? Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:937–940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LaMarca B, Speed J, Fournier L, et al. Hypertension in response to chronic reductions in uterine perfusion in pregnant rats: effect of tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockade. Hypertension. 2008;52:1161–1167. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.120881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sunderland NS, Thomson SE, Heffernan SJ, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha induces a model of preeclampsia in pregnant baboons (Papio hamadryas) Cytokine. 2011;56:192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.06.003. In this study, previous work in rodent and mouse models was verified in a nonhuman primate model. TNF-α infusion in baboons induced a preeclampsia-like phenotype with endothelial dysfunction and maternal hypertension.

- 26. Cindrova-Davies T, Sanders DA, Burton GJ, Charnock-Jones DS. Soluble FLT1 sensitizes endothelial cells to inflammatory cytokines by antagonizing VEGF receptor-mediated signalling. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;89:671–679. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq346. Here an interesting study demonstrates a new link between sFlt-1 and the maternal immune response, showing that sFlt-1 hightens the endothelial dysfunction brought about inflammatory cytokines.

- 27.Wallukat G, Homuth V, Fischer T, et al. Patients with preeclampsia develop agonistic autoantibodies against the angiotensin AT1 receptor. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:945–952. doi: 10.1172/JCI4106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dechend R, Viedt C, Muller DN, et al. AT1 receptor agonistic antibodies from preeclamptic patients stimulate NADPH oxidase. Circulation. 2003;107:1632–1639. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000058200.90059.B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LaMarca B, Wallukat G, Llinas M, et al. Autoantibodies to the angiotensin type I receptor in response to placental ischemia and tumor necrosis factor alpha in pregnant rats. Hypertension. 2008;52:1168–1172. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.120576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou CC, Ahmad S, Mi T, et al. Autoantibody from women with preeclampsia induces soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 production via angiotensin type 1 receptor and calcineurin/nuclear factor of activated T-cells signaling. Hypertension. 2008;51:1010–1019. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.097790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou CC, Zhang Y, Irani RA, et al. Angiotensin receptor agonistic autoantibodies induce preeclampsia in pregnant mice. Nat Med. 2008;14:855–862. doi: 10.1038/nm.1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor RN, Varma M, Teng NN, Roberts JM. Women with preeclampsia have higher plasma endothelin levels than women with normal pregnancies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;71:1675–1677. doi: 10.1210/jcem-71-6-1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baksu B, Davas I, Baksu A, et al. Plasma nitric oxide, endothelin-1 and urinary nitric oxide and cyclic guanosine monophosphate levels in hypertensive pregnant women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;90:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishikawa S, Miyamoto A, Yamamoto H, et al. The relationship between serum nitrate and endothelin-1 concentrations in preeclampsia. Life Sci. 2000;67:1447–1454. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00736-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alexander BT, Kassab SE, Miller MT, et al. Reduced uterine perfusion pressure during pregnancy in the rat is associated with increases in arterial pressure and changes in renal nitric oxide. Hypertension. 2001;37:1191–1195. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.4.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Makris A, Thornton C, Thompson J, et al. Uteroplacental ischemia results in proteinuric hypertension and elevated sFLT-1. Kidney Int. 2007;71:977–984. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abitbol MM, Ober MB, Gallo GR, et al. Experimental toxemia of pregnancy in the monkey, with a preliminary report on renin and aldosterone. Am J Pathol. 1977;86:573–590. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alexander BT, Rinewalt AN, Cockrell KL, et al. Endothelin type a receptor blockade attenuates the hypertension in response to chronic reductions in uterine perfusion pressure. Hypertension. 2001;37(2 Part 2):485–489. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberts L, LaMarca BB, Fournier L, et al. Enhanced endothelin synthesis by endothelial cells exposed to sera from pregnant rats with decreased uterine perfusion. Hypertension. 2006;47:615–618. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000197950.42301.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Murphy SR, LaMarca BB, Cockrell K, Granger JP. Role of endothelin in mediating soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1-induced hypertension in pregnant rats. Hypertension. 2010;55:394–398. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.141473. This study demonstrates the importance of the endothelin-1 as a link between increased sFlt-1 and maternal hypertension. Indeed, the hypertensive response brought about by increased sFlt-1 was completely blocked by an ETA antagonist, suggesting a possible therapeutic approach for the management of hypertension during preeclampsia.

- 41.LaMarca B, Parrish M, Ray LF, et al. Hypertension in response to autoantibodies to the angiotensin II type I receptor (AT1-AA) in pregnant rats: role of endothelin-1. Hypertension. 2009;54:905–909. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.137935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clouthier DE, Hosoda K, Richardson JA, et al. Cranial and cardiac neural crest defects in endothelin-A receptor-deficient mice. Development. 1998;125:813–824. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.5.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taniguchi T, Muramatsu I. Pharmacological knockout of endothelin ET(A) receptors. Life Sci. 2003;74:405–409. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olgun N, Patel HJ, Stephani R, et al. Effect of the putative novel selective ETA-receptor antagonist HJP272, a 1,3,6-trisubstituted-2-carboxy-quinol-4-one, on infection-mediated premature delivery. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;86:571–575. doi: 10.1139/Y08-057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thaete LG, Neerhof MG, Silver RK. Differential effects of endothelin A and B receptor antagonism on fetal growth in normal and nitric oxide-deficient rats. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2001;8:18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]