Abstract

It has been well established that chemical mutagenesis has adverse fitness effects in RNA viruses, often leading to population extinction. This is mainly a consequence of the high RNA virus spontaneous mutation rates, which situate them close to the extinction threshold. Single-stranded DNA viruses are the fastest-mutating DNA-based systems, with per-nucleotide mutation rates close to those of some RNA viruses, but chemical mutagenesis has been much less studied in this type of viruses. Here, we serially passaged bacteriophage ϕX174 in the presence of the nucleoside analogue 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). We found that 5-FU was unable to trigger population extinction for the range of concentrations tested, but it negatively affected viral adaptability. The phage evolved partial drug resistance, and parallel nucleotide substitutions appearing in independently evolved lines were identified as candidate resistance mutations. Using site-directed mutagenesis, two single-nucleotide substitutions in the lysis protein E (T572C and A781G) were shown to be selectively advantageous in the presence of 5-FU. In RNA viruses, base analogue resistance is often mediated by changes in the viral polymerase, but this mechanism is not possible for ϕX174 and other single-stranded DNA viruses because they do not encode their own polymerase. In addition to increasing mutation rates, 5-FU produces a wide variety of cytotoxic effects at the levels of replication, transcription, and translation. We found that substitutions T572C and A781G lost their ability to confer 5-FU resistance after cells were supplemented with deoxythymidine, suggesting that their mechanism of action is at the DNA level. We hypothesize that regulation of lysis time may allow the virus to optimize progeny size in cells showing defects in DNA synthesis.

INTRODUCTION

Viruses account for most of the variability in mutation rates in nature, ranging from 10−8 to 10−4 substitutions per nucleotide per round of copying (s/n/r) (52). RNA viruses are situated at the top of this range, and it is commonly accepted that their mutation rates cannot be increased further without compromising viral fitness. Supporting this view, serial passages in the presence of nucleoside analogues or other mutagens have been shown to produce drastic fitness losses or even population extinction through lethal mutagenesis in a variety of RNA viruses including enteroviruses (11, 30), aphthoviruses (55), hantaviruses (9), arenaviruses (31), lentiviruses (15, 39), and leviviruses (5, 8). This has led to the suggestion that lethal mutagenesis could be used as a therapeutic strategy against RNA viruses (19, 43) although several resistance mechanisms have already been described, such as the ability to selectively exclude nucleoside analogues from the polymerase active site, an overall increase in replication fidelity, or increased tolerance to mutation (2, 4, 10, 29, 45, 51, 54).

The effects of chemical mutagenesis have been less extensively investigated in DNA viruses. Serial passages of the bacteriophage T7 in the presence of a nucleoside analogue resulted in substantial adaptive evolution, in contrast to the typical fitness losses observed in RNA viruses, although the interpretation of these results was complicated by the lack of control lines without mutagen (57). Single-stranded DNA bacteriophages are interesting candidates for studying mutagenesis because their mutation rates are highest among DNA viruses (52), yet these viruses depend on a host polymerase for replication. The mutation rate of bacteriophage ϕX174 is on the order of 10−6 s/n/r, which is approximately 1,000-fold higher than that of Escherichia coli but close to the mutation rates of some RNA viruses (12, 46, 61). The lack of a polymerase implies that the virus must use other mechanisms for modulating its mutation rate. For instance, the ϕX174 genome lacks GATC sequence motifs required for methyl-directed mismatch repair (MMR) in E. coli (16, 41), and the experimental addition of these motifs produces a significant increase in the phage replication fidelity, indicating that avoidance of MMR is one such mechanism (14).

Here, we experimentally evolved bacteriophage ϕX174 in the presence of the nucleoside analogue 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). In addition to its mutagenic effect, 5-FU interferes with bacterial metabolism, severely altering replication, transcription, and translation. At the DNA level, 5-FU inhibits thymidylate synthase, thus blocking the synthesis of deoxythymidine monophosphate. As a result, in the absence of externally supplied thymidine, the cell undergoes thymidineless death, a complex process involving single- and double-strand DNA breaks, induction of the SOS DNA damage response, activation of DNA repair, loss of plasmids and transforming ability, inefficient assembly of Okazaki fragments, or filamentation, among other effects (3, 27). Importantly, thymidine deprivation is also mutagenic (1, 22) because it leads to uracil incorporation into DNA in place of thymidine, uracil excision, and DNA repair mediated by error-prone polymerases. Additionally, 5-FU massively incorporates into mRNA, rRNA, and tRNA (36), thus interfering with translation at several levels, including abnormal rRNA assembly (35), tRNA misfolding (40), and mRNA misreading (50).We found that, despite producing an up to 10-fold increase in the mutation rate of the phage, 5-FU failed to induce lethal mutagenesis. However, the drug had a negative impact on viral fitness and adaptability. The phage evolved partial resistance to 5-FU, and we identified at least two single amino acid substitutions responsible for this phenotype, both mapping to the lysis gene E. The mechanism of resistance appears to be related to the ability of these mutants to grow under conditions of thymidine starvation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteriophage and cells.

Bacteriophage ϕX174 and the E. coli C strain IJ1862 (6) were obtained from James J. Bull (University of Texas). The E. coli gro89 strain was obtained from Bentley A. Fane. In a previous work, we obtained a low-fitness clone by subjecting it to serial plaque-to-plaque passages and nitrous acid mutagenesis (mutation accumulation line 2 in reference 20). This clone was used to initiate the evolution experiments and is here denoted the founder clone.

Experimental evolution.

Phage were propagated in liquid cultures in the presence of 0, 2, 5, or 10 ng/μl 5-FU. Each passage was performed by inoculating 0.5 ml of exponentially growing IJ1862 cells in LB medium with ∼104 PFU of phage, as detailed in previous work (20). Viruses were harvested at their late-exponential growth phase, when the titer reached ∼108 PFU/ml. Harvest times varied between 1 h 15 min and 3 h 50 min depending on the 5-FU concentration and passage number. By keeping the initial and final titers similar across different treatments, we ensured that all lines underwent a similar number of generations. At each passage, cells were removed by centrifugation, and supernatants were aliquoted, stored at −70°C, and titrated. These titers were used to adjust sampling times for the following passage.

Determination of mutation rates and frequencies.

Mutation rates were determined using the Luria-Delbrück fluctuation test null-class method as described previously (12, 14). For each test, 24 independent cultures of E. coli C IJ1862 were infected with an Ni of ∼300 PFU, incubated until an Nf of ∼106 to 107 PFU was produced, and plated (in the absence of 5-FU) on the nonpermissive strain gro89 in which only viruses carrying well-defined mutations at the N-terminal region of protein A can form plaques (12, 25, 46, 58). Mutation rates to gro89 resistance (m) were determined by the null-class method, which consists of counting the fraction of cultures with zero resistant mutants (P0). Since mutation is a rare event, the number of mutations per culture can be assumed to follow a Poisson distribution with the parameter λ = m(Nf − Ni), and therefore m can be estimated from the following equation: P0 = exp(−m(Nf − Ni)). Mutation rates per round of copying (μ) were calculated as μ = 3m/T (52), where T = 7 is the number of possible different mutations leading to gro89 resistance, as determined previously (12). Mutation frequencies were determined at passages 5, 10, 20, 35, and 50 by directly plating the virus on gro89 cells and calculated as the ratio of gro-resistant to total viruses. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with 5-FU concentration and evolution line as main factors and passage number as a covariate was used to test for changes in mutation frequency.

Sequencing.

PCR products were obtained directly from viral supernatants, column purified, and sequenced by the Sanger method. FASTA sequences were obtained from chromatograms using the Staden package (http://staden.sourceforge.net) and analyzed with MEGA (http://www.megasoftware.net) and GeneDoc (http://www.psc.edu/biomed/genedoc).

Site-directed mutagenesis.

Phage replicative double-stranded DNA was isolated from infected cultures using a standard miniprep kit and used as the template for PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis, as described previously (20). Briefly, full-length amplicons were obtained from 500 pg of template using Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs) and a pair of adjacent, divergent, 5′ phosphorylated primers, one of which carried the desired nucleotide substitution. PCR products were circularized by self-ligation and used to transfect competent cells by the heat shock method. Individual plaques were picked after 5 to 9 h of incubation at 37°C, resuspended in LB medium, and stored at −70°C. To verify that the desired mutation had been introduced and that no additional changes were present in the region flanking the target site, PCR and sequencing were performed directly from resuspended plaques.

Fitness assays.

Liquid IJ1862 cultures were inoculated with ∼104 PFU and harvested at the late-exponential growth phase of the phage, with the sampling time varying according to the 5-FU concentration (1 h 18 min, 1 h 35 min, 2 h, and 2 h 45 min for 0, 2, 5, and 10 ng/μl 5-FU, respectively). The founder clone was included in the same experimental block as the assayed phage (evolved or site-directed mutants), and at least three independent blocks were performed. We calculated growth rates (r) as the change in natural log titer per hour for each assayed virus and used this rate as a dependent variable for statistical analysis. To test for adaptation, for each 5-FU dose, a two-way nested ANOVA was done with the following factors: founder versus evolved viruses, evolved line nested within founder/evolved, and experimental block. For each individual substitution introduced by site-directed mutagenesis, the factors included in the ANOVA were the presence/absence of the substitution, the genetic background, and the experimental block.

RESULTS

Experimental evolution in the presence of 5-FU.

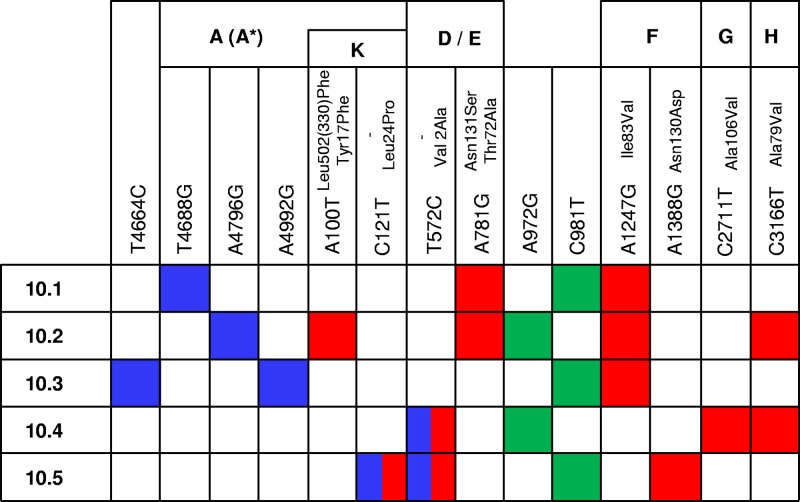

As shown in a previous work, serial passaging of a low-fitness clone of bacteriophage ϕX174 in E. coli C produced a significant increase in viral fitness after 50 passages (21). Here, we evolved this same clone at different doses of 5-FU to study the effects of the drug on viral fitness and adaptability. First, to calibrate the inhibitory effects of 5-FU, we determined viral fitness as the growth rate in the presence 0, 2, 5, and 10 ng/μl of the drug (Fig. 1). A dose-dependent inhibitory effect was observed (Pearson r = −0.901, P < 0.001), with a roughly 10-fold reduction in viral fitness at 10 ng/μl (from 6.5 to 0.60 h−1). We also quantified the mutagenic effects of 5-FU under the same range of drug concentrations by the Luria-Delbrück fluctuation test, using the nonpermissive strain gro89 to score mutants (12). Based on this, 5-FU showed a dose-dependent mutagenic effect on the phage (r = 0.740, P = 0.036), leading to a 10-fold increase in the mutation rate at 10 ng/μl (from 1.5 × 10−7 to 1.5 × 10−6 s/s/r).

Fig 1.

Inhibitory and mutagenic effects of 5-FU in the bacteriophage ϕX174. Growth rates (red) and mutation rates (blue) are shown for each 5-FU concentration. Values are means ± standard errors of the means.

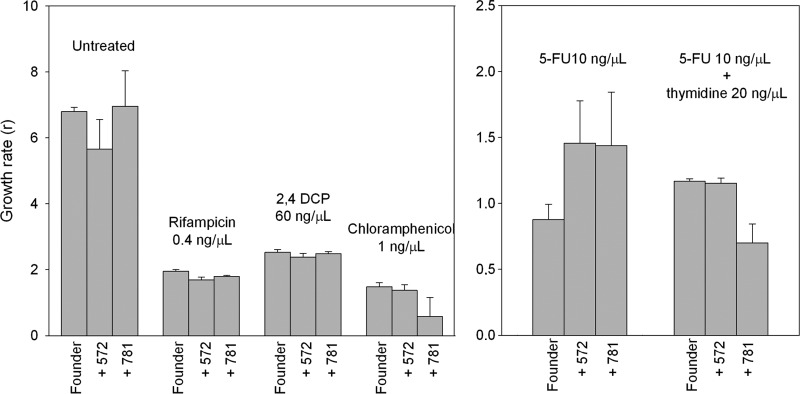

The low-fitness founder clone was serially passaged 50 times in E. coli C at 0, 2, 5, and 10 ng/μl of 5-FU, carrying out five replicate lines per treatment (thus making 20 lines in total). Viruses from passage 50 were assayed for fitness in the absence of 5-FU. Confirming previous results (21), the five lines evolved in the absence of 5-FU had significantly higher fitness than the founder clone (two-way nested ANOVA, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2A). Similar results were obtained for lines evolved at 2 ng/μl 5-FU (P = 0.002) and 5 ng/μl 5-FU (P < 0.001). In contrast, lines evolved at 10 ng/μl 5-FU showed no evidence of adaptation (P = 0.959). These results suggest that increasing the mutation rate of bacteriophage ϕX174 does not produce a benefit to the virus in terms of adaptability.

Fig 2.

Changes in viral fitness after 50 passages at different concentrations of 5-FU. The fitness of each line was expressed relative to that of the founder clone as the growth rate ratio. The dotted line indicates relative fitness of W = 1 (founder clone), and each data point corresponds to one evolution line. In panel A fitness was measured in the absence of 5-FU. In panel B each line was assayed at the same concentration of 5-FU used during the evolution experiment.

Serial passaging in the presence of 5-FU might have promoted the emergence of resistant viruses with an increased ability to tolerate mutagenesis or other physiological alterations produced by the drug. To test this, we performed fitness assays in the presence of the same 5-FU concentrations used during the evolution experiment. Under these conditions, the 20 evolved lines were significantly fitter than the founder clone (two-way nested ANOVA, P < 0.001) for each 5-FU dose, and the magnitude of the fitness gain correlated positively with the 5-FU concentration used (Pearson r = 0.979, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2B). We therefore conclude that the phage evolved partial 5-FU resistance.

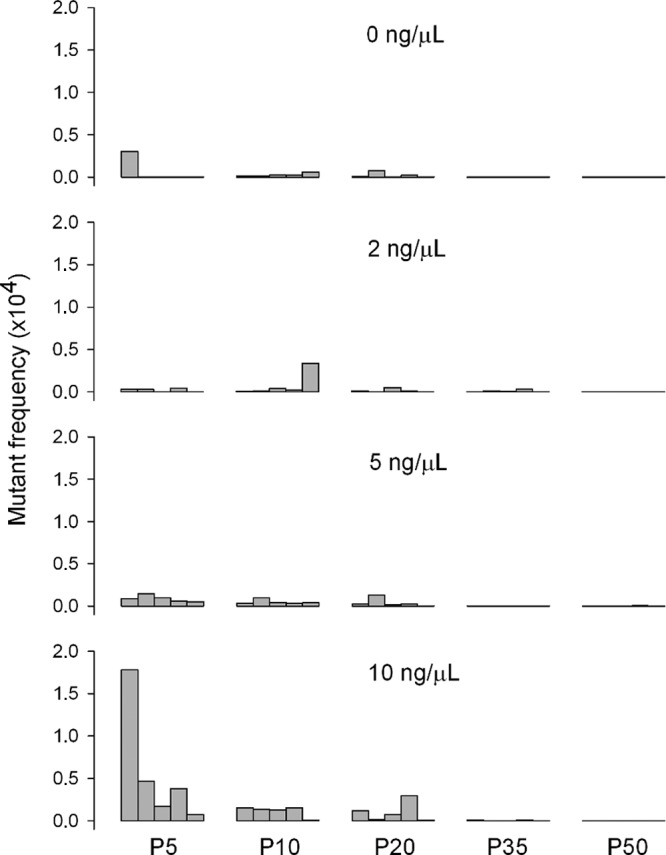

To track the mutagenic effect of 5-FU during the course of the evolution experiment, we scored mutants by plating supernatants from passages 5, 10, 20, 35, and 50 on the nonpermissive gro89 strain (Fig. 3). Mutant frequency depended on 5-FU concentration (two-way ANOVA, P = 0.024) and passage number (P = 0.003). Whereas there were few or no differences in mutant frequencies among lines evolved at 0, 2, and 5 ng/μl 5-FU, lines evolved at 10 ng/μl 5-FU initially showed a 10-fold increase in average frequency (from 6.1 × 10−6 to 5.7 × 10−5 at passage 5), which was consistent with the mutagenic effect of 5-FU quantified above. However, mutation frequency dropped in later passages. This suggests that the phage evolved resistance to 5-FU mutagenesis. Alternatively, genotypes with increased fitness under the physiological alterations produced by 5-FU might have emerged, and their fixation in the population might have produced selective sweeps that removed genetic variation.

Fig 3.

Frequency of gro89-resistant mutants as a function of passage (P) number (5, 10, 20, 35, and 50) for different 5-FU concentrations (0, 2, 5, and 10 ng/μl). Each bar corresponds to one evolution line.

Genetic basis and putative mechanism of 5-FU resistance.

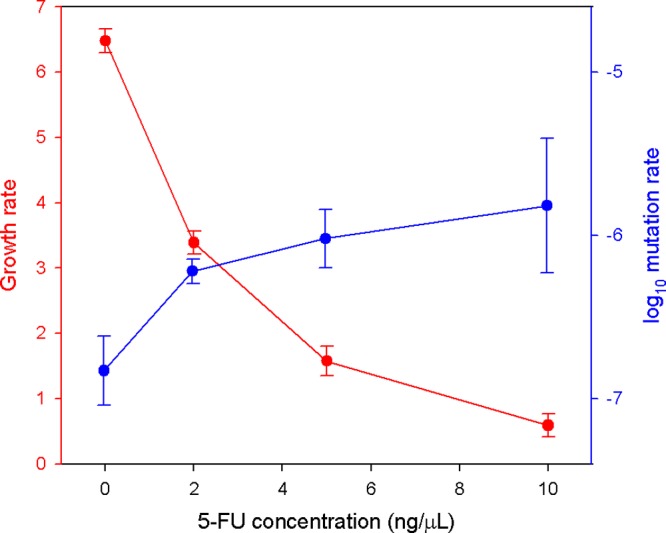

To explore the genetic basis of 5-FU resistance, we obtained the full-length sequences of the five lines (10.1 to 10.5) evolved at 10 ng/μl 5-FU (Fig. 4). After 50 passages, each line fixed between four and six mutations, and parallel evolution occurred at genome positions 572, 781, 972, 981, 1247, and 3166 (reference sequence AF176034). Parallel evolution is pervasive among microviruses and is a good indicator of adaptation (62). However, given the low fitness of the starting clone, some of these substitutions might not correspond to 5-FU-specific adaptations but might instead be generally advantageous mutations. This seems to be the case with regard to sites 972 and 981, which establish a DNA base pair in a hairpin-like secondary structure mapping to the intercistronic region between genes J and F. This structure is functionally important because it is known to act as a transcription termination signal and to influence ribosome binding in the downstream gene F (33, 47, 49). In microvirus sequences, positions 972 and 981 establish a G·C base pair (48), but our founder clone had a G972A substitution which disrupts this pair and probably contributes to its low fitness. Lines 10.2 and 10.4 reverted to the wild-type sequence, whereas lines 10.1, 10.3, and 10.5 fixed the compensatory mutation C981T which restores base pairing in the hairpin stem. Therefore, parallel evolution at genome positions 972 and 981 was unrelated to 5-FU. Indeed, the C981T substitution also occurred in four of the five lines evolved in the absence of the drug, and this same change was reported in a previous work (21). We also note that genome position 121 is a T in most ϕX174 sequences but was a C in our founder clone. Therefore, the C121T substitution represents another reversion to the wild type and is unlikely to be related to 5-FU resistance.

Fig 4.

Nucleotide substitutions fixed after 50 passages in the presence of 10 ng/μl 5-FU in each of the five evolution lines. Genes, genome positions in sequence AF176034, and amino acid replacements are indicated. Nonsynonymous substitutions are shown in red, synonymous substitutions are in blue, and intergenic substitutions are in green. Notice that some substitutions map to overlapping genes with different reading frames.

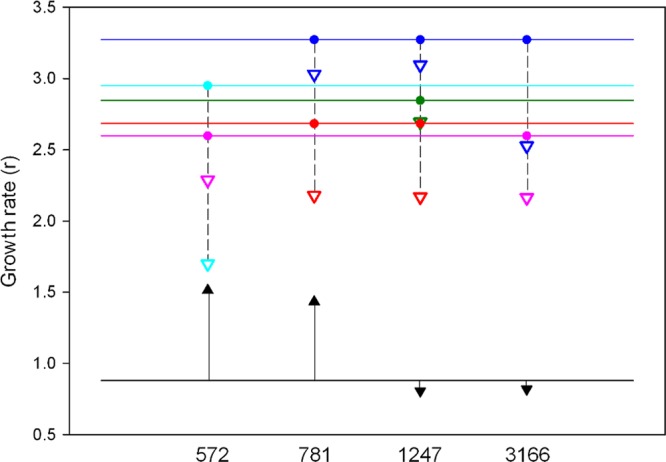

To explore whether the remaining parallel substitutions T572C, A781G, A1247G, and C3166T conferred 5-FU resistance, we introduced each individually in the genome of the founder clone by site-directed mutagenesis and assayed these mutants for fitness in the presence of 10 ng/μl 5-FU. The single substitution T572C produced a 69% increase in relative fitness, defined as the growth rate ratio to the founder clone (W), in the presence of the drug (W = 1.693 ± 0.092; two-way ANOVA, P < 0.001), and a similar increase (W = 1.626 ± 0.116; P < 0.001) was observed for substitution A781G (Fig. 5). In contrast, substitutions A1247G and C3166T showed no significant effects on viral fitness (P > 0.3). We then followed the reverse strategy, which consists of individually removing each of the above substitutions from the evolved lines in which they were present. As expected, this tended to negatively impact fitness for the 12 possible reversions (Fig. 5) although the effect was statistically significant only for C572T (three-way ANOVA, P = 0.013). This reversion reduced relative fitness from 2.930 ± 0.296 to 2.526 ± 0.486 in line 10.4 and from 3.308 ± 0.191 to 1.883 ± 0.219 in line 10.5. Finally, the single mutants T572C, A781G, A1247G, and C3166T constructed in the genetic background of the founder clone were assayed for fitness in the absence of 5-FU to determine whether they incurred in any fitness cost. We found that substitution T572C produced a 17% drop in fitness (W = 0.831 ± 0.129; two-way ANOVA, P < 0.001), A781G and A1247G had no significant effects (P > 0.1), and A3166G produced a 6% fitness increase (P = 0.015) in the absence of 5-FU.

Fig 5.

Fitness effects of single-nucleotide substitutions in the presence of 10 ng/μl 5-FU, as determined by site-directed mutagenesis. The black horizontal line indicates the growth rate of the founder clone, and black arrows indicate the effect of each of the substitutions T572C, A781G, A1247G, and C3166T in this genetic background. The colored horizontal lines indicate the growth rates of lines 1 (red), 2 (dark blue), 3 (green), 4 (pink), and 5 (light blue). In each line, the presence or absence of each mutation is indicated with dots, and the downward, dashed arrows indicate the effect of reverting each substitution in each evolved line.

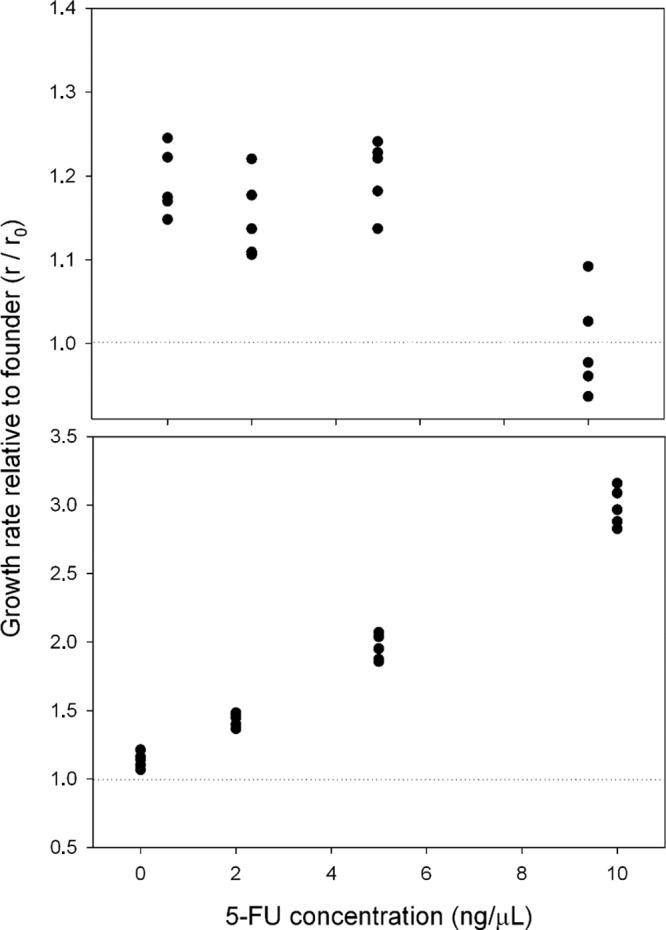

The above data indicate that substitutions T572C and A781G confer partial resistance to 5-FU. As indicated above, in addition to being a mutagen, 5-FU produces a variety of toxic effects in the cell, including thymidine starvation and abnormal ribosome assembly, among others. To try to shed light on the 5-FU resistance mechanisms associated with substitutions T572C and A781G, we determined their fitness effects in the presence of 60 ng/μl 2,4-dichlorophenol (2,4-DCP), 0.4 ng/μl rifampin, or 1 ng/μl chloramphenicol. 2,4-Dichlorophenol is a DNA-damaging but nonmutagenic compound (26, 34), rifampin blocks bacterial transcription by inhibiting DNA-dependent RNA polymerases (7), and chloramphenicol blocks translation by inhibiting the peptidyl transferase activity of the bacterial ribosome (37). Doses were chosen such that they produced toxic effects on the bacteria similar to 10 ng/μl of 5-FU, as determined by standard growth assays (data not shown). The three drugs had a negative impact on the viral growth rate (Fig. 6) (three-way ANOVA, P < 0.001), but mutants T572C and A781G showed no fitness advantage over the founder clone in the presence of any of these drugs. In contrast, the fitness effect of substitution T572C tended to be deleterious (average over the three treatments, W = 0.917 ± 0.058; P = 0.009), reproducing the fitness cost experienced by this mutation in the absence of 5-FU. Substitution A781G had no significant fitness effect, and, although it appeared to be deleterious in the presence of chloramphenicol, the estimation error was too large to reach statistical significance (three-way ANOVA, P = 0.645). We then measured viral fitness in cultures containing 20 ng/μl 5-FU supplemented with 20 ng/μl of 2′-deoxythymidine, which should partially reverse thymidine starvation and 5-FU effects at the DNA level, including mutagenesis (3). Whereas, as shown above, the single mutants T572C and A781G had a significant fitness advantage over the founder clone in the presence of 10 ng/μl 5-FU, such advantage was lost after the addition of 2′-deoxythymidine (Fig. 6). Substitution T572C became selectively neutral (W = 0.987 ± 0.034; two-way ANOVA, P = 0.723), whereas A781G was deleterious (W = 0.598 ± 0.124; P = 0.002).

Fig 6.

Inhibitory effects of several compounds for the founder clone and single mutants T572C and A781G. The viral growth rate is shown for each virus and treatment. Values are means ± standard errors of the means.

The ability of 2′-deoxythymidine to offset the growth advantage shown by mutants T572C and A781G in the presence of 5-FU suggests that their mechanism of action is at the DNA level and related to thymidine starvation, mutagenesis, or both. We quantified the effects of these two substitutions on the viral mutation rate using the Luria-Delbrück fluctuation test, as above (Table 1). Whereas the mutation rate estimate for the founder clone ranged between 9.1 × 10−8 and 2.4 × 10−7 s/n/r, introducing substitution T572C reduced the estimate by more than two orders of magnitude (6.1 × 10−10 s/n/r), and substitution A781G had no effect (1.2 × 10−7 s/n/r). However, we also noticed that the estimate for the founder clone is in turn 10-fold lower than that previously reported for bacteriophage ϕX174 using the same method (12). It is thus possible that our estimates were biased, such that low-fitness viruses produced lower estimates, probably due to a lower plating efficiency in nonpermissive cells.

Table 1.

Luria-Delbrück fluctuation tests for the founder clone and single mutants T572C and A781G

| Virus | Ni | Nf | No. of cultures with mutants | No. of cultures with no mutants | P0 | m | μ (s/n/r)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Founder | 676 | 2.8 × 106 | 19 | 5 | 0.208 | 5.6 × 10−7 | 2.4 × 10−7 |

| Founder | 407 | 8.5 × 106 | 20 | 4 | 0.167 | 2.1 × 10−7 | 9.1 × 10−8 |

| T572C mutant | 235 | 9.5 × 107 | 3 | 21 | 0.875 | 1.4 × 10−9 | 6. 1 × 10−10 |

| A781G mutant | 225 | 3.9 × 106 | 16 | 8 | 0.333 | 2.8 × 10−7 | 1.2 × 10−7 |

The phenotype can be conferred by each of seven different single-nucleotide substitutions.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that the mutation rate of bacteriophage ϕX174 can be increased up to 10-fold using 5-FU and that this appears to have a negative impact on viral adaptability. This result is similar to previous findings with a variety RNA viruses exposed to nucleoside analogues (5, 8, 9, 11, 15, 30, 31, 39, 55) although here we failed to trigger lethal mutagenesis. Higher efficiency of 5-FU incorporation into RNA than into DNA may offer an explanation. Up to 47% of the uracil of tobacco mosaic virus (28) and 36% of the uracil of poliovirus (44) can be replaced by 5-FU, and although we did not determine this percentage in ϕX174, it is probably lower. Also, lethal mutagenesis of mammalian RNA viruses has been achieved at much higher 5-FU concentrations (up to 2,000 ng/μl) than those used here (32, 55). The severe inhibition of ϕX174 growth at 10 ng/μl of 5-FU could be because bacterial cells have greater sensitivity to the drug than mammal cells and also to the fact that ϕX174 replicates efficiently only in dividing cells, which are more severely affected by nucleoside analogues than nondividing cells. Another possible explanation for our inability to sufficiently debilitate the virus is that the founder clone was highly nonadapted. Work with ϕX174 and other viruses has shown that serial passaging at low population sizes tends to favor the accumulation of deleterious mutations but fails to reduce fitness in already debilitated viruses because beneficial mutations are more frequent in low-fitness genetic backgrounds and can offset the effects of deleterious mutation accumulation (8, 38, 56).

After 50 passages in the presence of 10 ng/μl 5-FU, the phage became partially resistant to the drug. Work with several viruses has shown that adaptation to one environment may come at the cost of reduced fitness in alternative environments (13, 23, 24, 38, 60), and this also applies to drug resistance. It is possible, thus, that the inability of ϕX174 lines treated with 10 ng/μl of 5-FU to increase fitness in the absence of the drug could be due to the costs associated with 5-FU resistance. Indeed, one of the resistance mutations (T572C) had a clearly negative impact on fitness in the absence of 5-FU. Given the extensive changes in cellular physiology produced by 5-FU, the mechanisms of resistance are difficult to elucidate. In RNA viruses, nucleoside analogue resistance often involves changes in the viral replicase (2, 4, 10, 29, 45, 54; for a contrasting view see reference 5), but this is not possible in ϕX174 because it does not encode its own polymerase. Therefore, 5-FU resistance, whether or not related to the mutagenic effects of the drug, has to be achieved through other mechanisms.

Since 5-FU reduces translation efficiency, some of the observed substitutions may lower the critical concentrations of proteins needed to nucleate capsid assembly. For instance, substitution A781G maps to Asn131 in loop 6 of external scaffolding protein D. This protein folds into four structurally nonidentical monomers (D1 to D4), and, in monomer D4, residues immediately adjacent to Asn131 are known to interact with the F coat protein (17). Loop 6 is flanked by α-helices 6 and 7. The latter establishes extensive contacts with protein F, whereas the former mediates 2-fold contacts among D monomers (17, 18). Residues in the α-helix 6 of the D1 subunit have also been shown to establish contacts with the spike protein G (17). Therefore, substitution A781G may alter the efficiency of capsid assembly. Another interesting substitution is A1247G, which modifies residue 83 in the highly conserved α-helix 1 of the F protein. Several residues in this helix establish 2-fold F-F interactions with residues in α-helices 4 and 5 (42), and, despite the fact that this residue has not been shown to participate directly in these interactions, it may somehow influence capsid stability. The independent appearance of substitution A1247G in three of five lines suggests that it confers some degree of resistance to 5-FU. However, its putative effect appears to be dependent on the presence of other substitutions in the genome since the single mutant was not selectively advantageous. Finally, another substitution that may deserve further study is A1388G. This substitution maps to α-helix 2 of the coat protein F which, together with a β-barrel region of this same protein, forms a cleft to which the internal scaffolding protein B binds (17).

Treatment with chloramphenicol did not reproduce the effects of the two clearest 5-FU resistance mutations (T572C and A781G), suggesting that their mechanism of action might not be related to protein synthesis and capsid assembly. Alternatively, chloramphenicol may not adequately mimic the effects of 5-FU on protein synthesis. However, the fact that this advantage was reversed by the addition of thymidine in the presence of 5-FU argues in favor of a DNA-level mechanism. It is also noteworthy that although both T572C and A781G map to an overlap region between genes D and E, T572C is synonymous in the D reading frame and thus modifies only the lysis protein E. It is thus possible that both substitutions share a resistance mechanism which would be exerted through changes in lysis time or efficiency. The relationship between this putative mechanism and DNA metabolism is unclear, but we can speculate that by reducing the synthesis rate of progeny genomes, 5-FU may modify the optimal lysis time (i.e., the lysis time that maximizes burst size). In turn, changes in burst size or replication modes may modify the rate at which mutations accumulate in the population (53, 59). Luria-Delbrück fluctuation tests suggested that substitution T572C had a strong impact on the viral mutation rate. Although the null-class method we used for calculating these estimates should be insensitive to burst size and replication mode, this may not hold true at low plating efficiencies. In any case, however, these mutation rate estimates have to be used with caution because they may have been biased by differences in fitness and plating efficiencies across viruses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jim Bull and Bentley A. Fane for supplying the viruses and the cells and Ester Lázaro for useful comments.

R.S. was financially supported by grant BFU2011-25271 and the Ramón y Cajal Research Program from the Spanish MICINN and by Starting Grant 2011-281191 from the European Research Council. P.D-C. was supported by a fellowship from the Spanish Generalitat Valenciana. M.P.-G. was supported by a fellowship from the Spanish Ministerio de Educación y Cultura (MEC).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 June 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Adelberg EA, Coughlin CA. 1956. Bacterial mutation induced by thymine starvation. Nature 178:531–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Agudo R, et al. 2010. A multi-step process of viral adaptation to a mutagenic nucleoside analogue by modulation of transition types leads to extinction-escape. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001072 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ahmad SI, Kirk SH, Eisenstark A. 1998. Thymine metabolism and thymineless death in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52:591–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arias A, et al. 2008. Determinants of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (in)fidelity revealed by kinetic analysis of the polymerase encoded by a foot-and-mouth disease virus mutant with reduced sensitivity to ribavirin. J. Virol. 82:12346–12355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arribas M, Cabanillas L, Lázaro E. 2011. Identification of mutations conferring 5-azacytidine resistance in bacteriophage Qbeta. Virology 417:343–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bull JJ, Badgett MR, Springman R, Molineux IJ. 2004. Genome properties and the limits of adaptation in bacteriophages. Evolution 58:692–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Calvori C, Frontali L, Leoni L, Tecce G. 1965. Effect of rifamycin on protein synthesis. Nature 207:417–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cases-González C, Arribas M, Domingo E, Lázaro E. 2008. Beneficial effects of population bottlenecks in an RNA virus evolving at increased error rate. J. Mol. Biol. 384:1120–1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chung DH, et al. 2007. Ribavirin reveals a lethal threshold of allowable mutation frequency for Hantaan virus. J. Virol. 81:11722–11729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Coffey LL, Beeharry Y, Borderia AV, Blanc H, Vignuzzi M. 2011. Arbovirus high fidelity variant loses fitness in mosquitoes and mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:16038–16043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Crotty S, Cameron CE, Andino R. 2001. RNA virus error catastrophe: direct molecular test by using ribavirin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:6895–6900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cuevas JM, Duffy S, Sanjuán R. 2009. Point mutation rate of bacteriophage ΦX174. Genetics 183:747–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cuevas JM, Moya A, Elena SF. 2003. Evolution of RNA virus in spatially structured heterogeneous environments. J. Evol. Biol. 16:456–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cuevas JM, Pereira-Gómez M, Sanjuan R. 2011. Mutation rate of bacteriophage ΦX174 modified through changes in GATC sequence context. Infect. Genet. Evol. 11:1820–1822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dapp MJ, Clouser CL, Patterson S, Mansky LM. 2009. 5-Azacytidine can induce lethal mutagenesis in human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 83:11950–11958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deschavanne P, Radman M. 1991. Counterselection of GATC sequences in enterobacteriophages by the components of the methyl-directed mismatch repair system. J. Mol. Evol. 33:125–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dokland T, et al. 1999. The role of scaffolding proteins in the assembly of the small, single-stranded DNA virus ΦX174. J. Mol. Biol. 288:595–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dokland T, et al. 1997. Structure of a viral procapsid with molecular scaffolding. Nature 389:308–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Domingo E, Grande-Pérez A, Martín V. 2008. Future prospects for the treatment of rapidly evolving viral pathogens: insights from evolutionary biology. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 8:1455–1460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Domingo-Calap P, Cuevas JM, Sanjuán R. 2009. The fitness effects of random mutations in single-stranded DNA and RNA bacteriophages. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000742 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Domingo-Calap P, Sanjuán R. 2011. Experimental evolution of RNA versus DNA viruses. Evolution 65:2987–2994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Drake JW, Greening EO. 1970. Suppression of chemical mutagenesis in bacteriophage T4 by genetically modified DNA polymerases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 66:823–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Duffy S, Burch CL, Turner PE. 2007. Evolution of host specificity drives reproductive isolation among RNA viruses. Evolution 61:2614–2622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Duffy S, Turner PE, Burch CL. 2006. Pleiotropic costs of niche expansion in the RNA bacteriophage Φ6. Genetics 172:751–757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ekechukwu MC, Oberste DJ, Fane BA. 1995. Host and ΦX 174 mutations affecting the morphogenesis or stabilization of the 50S complex, a single-stranded DNA synthesizing intermediate. Genetics 140:1167–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Espigares M, Mariscal A. 1989. The effect of 2,4-dichlorophenol on growth and plasmidic beta-lactamase activity in Escherichia coli. J. Appl. Toxicol. 9:427–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fonville NC, Bates D, Hastings PJ, Hanawalt PC, Rosenberg SM. 2010. Role of RecA and the SOS response in thymineless death in Escherichia coli. PLoS Genet. 6:e1000865 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gordon MP, Staehelin M. 1959. Studies on the incorporation of 5-fluorouracil into a virus nucleic acid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 36:351–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Graci JD, et al. 2012. Mutational robustness of an RNA virus influences sensitivity to lethal mutagenesis. J. Virol. 86:2869–2873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Graci JD, et al. 2007. Lethal mutagenesis of poliovirus mediated by a mutagenic pyrimidine analogue. J. Virol. 81:11256–11266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Grande-Pérez A, Lazaro E, Lowenstein P, Domingo E, Manrubia SC. 2005. Suppression of viral infectivity through lethal defection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:4448–4452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Grande-Pérez A, Sierra S, Castro MG, Domingo E, Lowenstein PR. 2002. Molecular indetermination in the transition to error catastrophe: systematic elimination of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus through mutagenesis does not correlate linearly with large increases in mutant spectrum complexity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:12938–12943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hayashi MN, Hayashi M, Muller UR. 1983. Role for the J-F intercistronic region of bacteriophages ϕX174 and G4 in stability of mRNA. J. Virol. 48:186–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hilliard CA, et al. 1998. Chromosome aberrations in vitro related to cytotoxicity of nonmutagenic chemicals and metabolic poisons. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 31:316–326 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hills DC, Horowitz J. 1966. Ribosome synthesis in Escherichia coli treated with 5-fluorouracil. Biochemistry 5:1625–1632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Horowitz J, Cargaff E. 1959. Massive incorporation of 5-fluorouracil into a bacterial ribonucleic acid. Nature 184:1213–1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jardetzky O. 1963. Studies on the mechanism of action of chloramphenicol. I. The conformation of chloramphenicol in solution. J. Biol. Chem. 238:2498–2508 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lázaro E, Escarmís C, Pérez-Mercader J, Manrubia SC, Domingo E. 2003. Resistance of virus to extinction on bottleneck passages: study of a decaying and fluctuating pattern of fitness loss. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:10830–10835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Loeb LA, et al. 1999. Lethal mutagenesis of HIV with mutagenic nucleoside analogs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:1492–1497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lowrie RJ, Bergquist PL. 1968. Transfer ribonucleic acids from Escherichia coli treated with 5-fluorouracil. Biochemistry 7:1761–1770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McClelland M. 1984. Selection against dam methylation sites in the genomes of DNA of enterobacteriophages. J. Mol. Evol. 21:317–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McKenna R, Ilag LL, Rossmann MG. 1994. Analysis of the single-stranded DNA bacteriophage ΦX174, refined at a resolution of 3.0 A. J. Mol. Biol. 237:517–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mullins JI, et al. 2011. Mutation of HIV-1 genomes in a clinical population treated with the mutagenic nucleoside KP1461. PLoS One 6:e15135 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Munyon W, Salzman NP. 1962. The incorporation of 5-fluoro-uracil into poliovirus. Virology 18:95–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pfeiffer JK, Kirkegaard K. 2003. A single mutation in poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase confers resistance to mutagenic nucleotide analogs via increased fidelity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:7289–7294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Raney JL, Delongchamp RR, Valentine CR. 2004. Spontaneous mutant frequency and mutation spectrum for gene A of ΦX174 grown in E. coli. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 44:119–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ravetch JV, Model P, Robertson HD. 1977. Isolation and characterisation of the ΦX174 ribosome binding sites. Nature 265:698–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rokyta DR, Burch CL, Caudle SB, Wichman HA. 2006. Horizontal gene transfer and the evolution of microvirid coliphage genomes. J. Bacteriol. 188:1134–1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Romantschuk ML, Muller UR. 1983. Mutations in the J-F intercistronic region of bacteriophages ϕX174 and G4 affect the regulation of gene expression. J. Virol. 48:180–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rosen B, Rothman F, Weigert MG. 1969. Miscoding caused by 5-fluorouracil. J. Mol. Biol. 44:363–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sanjuán R, Cuevas JM, Furió V, Holmes EC, Moya A. 2007. Selection for robustness in mutagenized RNA viruses. PLoS Genet. 3:e93 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sanjuán R, Nebot MR, Chirico N, Mansky LM, Belshaw R. 2010. Viral mutation rates. J. Virol. 84:9733–9748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sardanyés J, Solé RV, Elena SF. 2009. Replication mode and landscape topology differentially affect RNA virus mutational load and robustness. J. Virol. 83:12579–12589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sierra M, et al. 2007. Foot-and-mouth disease virus mutant with decreased sensitivity to ribavirin: implications for error catastrophe. J. Virol. 81:2012–2024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sierra S, Dávila M, Lowenstein PR, Domingo E. 2000. Response of foot-and-mouth disease virus to increased mutagenesis: influence of viral load and fitness in loss of infectivity. J. Virol. 74:8316–8323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Silander OK, Tenaillon O, Chao L. 2007. Understanding the evolutionary fate of finite populations: the dynamics of mutational effects. PLoS Biol. 5:e94 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Springman R, Keller T, Molineux I, Bull JJ. 2010. Evolution at a high imposed mutation rate: adaptation obscures the load in phage T7. Genetics 184:221–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tessman ES, Peterson PK. 1976. Bacterial rep− mutations that block development of small DNA bacteriophages late in infection. J. Virol. 20:400–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Thebaud G, Chadoeuf J, Morelli MJ, McCauley JW, Haydon DT. 2010. The relationship between mutation frequency and replication strategy in positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses. Proc. Biol. Sci. 277:809–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Turner PE, Elena SF. 2000. Cost of host radiation in an RNA virus. Genetics 156:1465–1470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Valentine CR, et al. 2010. In vivo mutation analysis using the ΦX174 transgenic mouse and comparisons with other transgenes and endogenous genes. Mutat. Res. 705:205–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wichman HA, Brown CJ. 2010. Experimental evolution of viruses: Microviridae as a model system. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 365:2495–2501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]