Abstract

Genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation assays indicate that the promoter-proximal pausing of RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) is an important postinitiation step for gene regulation. During latent infection, the majority of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) genes is silenced via repressive histone marks on their promoters. Despite the absence of their expression during latency, however, several lytic promoters are enriched with activating histone marks, suggesting that mechanisms other than heterochromatin-mediated suppression contribute to preventing lytic gene expression. Here, we show that the RNAPII-mediated transcription of the KSHV OriLytL, K5, K6, and K7 (OriLytL-K7) lytic genes is paused at the elongation step during latency. Specifically, the RNAPII-mediated transcription is stalled by the host's negative elongation factor (NELF) at the promoter regions of OriLytL-K7 lytic genes during latency, leading to the hyperphosphorylation of the serine 5 residue and the hypophosphorylation of the serine 2 of the C-terminal domain of the RNAPII large subunit, a hallmark of stalled RNAPII. Consequently, depletion of NELF expression induced transition of stalled RNAPII into a productive transcription elongation at the promoter-proximal regions of OriLytL-K7 lytic genes, leading to their RTA-independent expression. Using an RTA-deficient recombinant KSHV, we also showed that expression of the K5, K6, and K7 lytic genes was highly inducible upon external stimuli compared to other lytic genes that lack RNAPII on their promoters during latency. These results indicate that the transcription elongation of KSHV OriLytL-K7 lytic genes is inhibited by NELF during latency, but can also be promptly reactivated in an RTA-independent manner upon external stimuli.

INTRODUCTION

Recent global analyses of the human and Drosophila genomes have revealed activating histone marks and transcriptionally engaged but paused RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) on the promoters of numerous repressed genes, indicating additional regulatory mechanisms after the transcriptional initiation (11, 22). At this postinitiation step, the modulation of transcriptional elongation has a pivotal role in the regulation of gene expression, as the interplay between positive and negative transcription elongation factors recruited to RNAPII can ultimately determine the rate of productive transcription (20, 64). The major factors involved in the regulation of transcription elongation are the negative elongation factor (NELF) complex, composed of 4 subunits (NELF-A, -B, -C/D, and -E), and DRB (5,6-dichloro-1-β-d-ribofuranosylbenzimidazole) sensitivity-inducing factor (DSIF) containing Spt4 and Spt5, as well as the positive transcription elongation factor (P-TEFb), which consists of cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (CDK9) and cyclin T1 (38, 44, 55, 63). Based on the current model, after RNAPII clears the promoter, NELF and DSIF cooperatively bind to RNAPII in the promoter-proximal region of target genes, resulting in RNAPII pausing (55, 63). The switch to robust elongation is mediated by P-TEFb, which can be recruited to the paused RNAPII by various transcription activators (e.g., c-myc, NF-κB, Brd4, and HIV-1 Tat) (3, 27, 28, 45, 59, 66). CDK9, the kinase subunit of P-TEFb, subsequently phosphorylates Spt5, NELF-E, and serine 2 of the C-terminal domain (CTD) of RNAPII, converting the preinitiated paused transcription elongation complex to an active elongation complex (56). In vitro data indicate that the phosphorylation of NELF-E dissociates NELF complex from RNAPII, while the phosphorylation of Spt5 converts it from a negative to a positive transcription elongation factor that travels with RNAPII along the target gene body (61, 62). A number of in vivo studies also showed that NELF regulates the RNAPII elongation step of several inducible genes involved in stress and immune responses or the regulation of development in various organisms (1, 2, 10, 60).

Transcription elongation has also emerged as a critical regulatory step of viral gene expression in viruses pathogenic to humans. P-TEFb was found to be essential for the transcription of HIV-1, human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1), and human papillomavirus (HPV) genes (9, 42, 59, 65, 70). In addition, P-TEFb has been shown to be involved in the induction of lytic genes of herpes simplex virus 1 (alphaherpesvirus subfamily) and human cytomegalovirus (betaherpesvirus subfamily) (15, 17, 30, 32). Transcription elongation factors are also involved in modulating the latent gene expression of two oncogenic herpesviruses belonging to the gammaherpesvirus subfamily, Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) and Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) (29, 43).

KSHV is a ubiquitous human pathogen that establishes a persistent infection and is involved in the pathogenesis of Kaposi's sarcoma (KS), primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), and multicentric Castleman's disease (MCD) (6). The KSHV life cycle consists of two different phases: latent and lytic. While KSHV constitutively expresses a few viral genes during latency, the expression of lytic genes is temporally regulated and primarily dependent on the immediate-early (IE) gene product R transactivator (RTA), an essential viral transcription factor (33, 51). KSHV stays in latency in the majority of infected tumor cells, and thus the activity of latent viral proteins is thought to be the primary mediator of KSHV tumorigenesis. However, a small percentage of KSHV-infected cells express specific lytic genes in PEL cells and KS biopsy specimens, suggesting that lytic gene products may also play crucial roles in the development of KSHV malignancies (6). Indeed, several lytic proteins (e.g., K2, K5, K7, vGPCR, viral RNA interferon 1 [vIRF1], and vBcl2) involved in antiapoptosis, immune evasion, and signal transduction modulation are strikingly associated with KSHV pathogenesis (8, 21, 31, 69). In fact, these lytic gene products are crucial for KSHV tumorigenesis either directly or indirectly by modulating viral persistency in the tumor cells (35). Since the induction of viral lytic replication by RTA ultimately leads to virus production accompanied by cell death, it is a long-standing enigma how the expression of lytic genes can be involved in the development of KSHV-associated cancer (69). Deregulated lytic gene expression or aborted lytic replication has been proposed as a mechanism of the lytic gene product-mediated tumorigenesis, but the molecular details driving deregulated lytic gene expression or aborted lytic replication are still poorly understood.

Recently, we and others described for the first time a comprehensive genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation with microarray technology (ChIP-chip) analysis of histone modifications associated with the KSHV genome during latency and lytic reactivation (23, 53). The results show that the chromatin of the latent KSHV genome is enriched with H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 repressive histone marks as well as acetylated histone H3 and H3K4me3 activating histone marks during latency. Interestingly, the enrichment of activating histone marks is detected at the promoters of several immediate-early (IE) and early (E) genes during latency, while the expression of these lytic genes is silenced. This observation raises the question of whether the RNAPII transcription complex is already assembled on these lytic promoters as an initiation cluster but blocked at the transcription elongation step, thereby repressing these lytic genes during latency. To test this hypothesis, we first determined the RNAPII binding sites on the KSHV genome during latency and after reactivation. While RNAPII was enriched at the promoter-proximal regions of a group of the KSHV lytic genes (OriLytL, K5, K6, and K7) during latency, their expression was specifically repressed by the NELF complex at the step of RNAPII-mediated transcriptional elongation. On the other hand, these viral lytic genes could be more robustly induced upon external stimuli in an RTA-independent manner compared to those lytic genes that did not have RNAPII on their promoters during latency. This indicates that, besides a general heterochromatin-mediated repression, the control of the transcriptional elongation step is an additional regulatory mechanism of viral lytic gene expression during latent herpesviral infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell cultures.

BCBL-1, BC1, and VG1 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (P/S). The TREXBCBL1-Rta cell line was cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% tetracycline (Tet)-free FBS, P/S, and 20 μg/ml hygromycin B. The iSLK cell line was a generous gift from Don Ganem (UCSF, San Francisco) (36). 293TBAC16 and 293TBAC16-RTAstop cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS, P/S, and 200 μg/ml hygromycin B. The iSLKBAC16 and iSLKBAC16-RTAstop cell lines were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, P/S, 1 μg/ml puromycin, 250 μg/ml G418, and 1.2 mg/ml hygromycin B.

Antibodies for ChIP assays and immunoblots.

Anti-Spt5, anti-cyclin T1, anti-RNAPII (total), and anti-NELF antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-pS5 RNAPII was from Millipore, and anti-pS2 RNAPII was from Abcam. Anti-RTA rabbit polyclonal antibody was a generous gift from Yoshihiro Izumiya and Hsing-Jien Kung (Univerisity of California, Davis, Sacramento, CA). LANA and K2, K3, and K5 KSHV protein-specific antibodies have been described previously (53).

ChIP-chip and ChIP assays.

Detailed descriptions of the ChIP-chip and ChIP assays have been published previously (53). Briefly, the 15-bp-tiling KSHV microarray used for the ChIP-chip assay included 60-mer overlapping probes, which cover the entire KSHV genome (U75698 and U75699 at GenBank), and was manufactured by Agilent Technologies. For the ChIP-chip assay, 20 μg of chromatin and 1 μg of RNAPII antibody (H-224) were used for each reaction. ChIP and DNA purification were performed as described previously (53). ChIP DNAs were amplified by Complete whole-genome amplification (Sigma-Aldrich) and purified with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) following the protocol provided by the manufacturer. Labeling, hybridization, and scanning of microarrays were performed at the Functional Genomics Core, Microarray Facility at City of Hope (Duarte, CA). Probe signals were extracted by the Agilent Feature Extraction software (version 10.5.1.1). The log2 (Cy5/Cy3) ratios of the mean signals of probes were calculated and further analyzed by R software (version 2.9.0) (http://www.r-project.org). To correct for dye bias, we used the Bioconductor package “aroma.light” for lowess normalization. The log2 ratios of the 0-h-postinfection (0-hpi) (latency) and 8-hpi (reactivation) samples were scaled to have the same median absolute deviation (MAD) using the function “normalizeBetweenArrays” from the “limma” Bioconductor package. Genetrix software (Epicenter Software, University of Southern California) was applied for visualizing the enrichment of RNAPII across the KSHV genome as used previously (53).

Lentiviral shRNA knockdown.

The short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) were expressed from pLKO.1 lentiviral vectors. The production of lentiviruses and the transduction of cells were performed as described previously (53). The shRNA target sequences for NELF-A and NELF-E are 5′-GGAGCAGAATCCCAACGTTCA and 5′-GGTGTCAAACGCTCACTATCA, respectively.

RNA purification, RT-PCR, and real-time qPCR.

The purification of total RNA, cDNA synthesis, semiquantitative and real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) analyses of cDNAs and genomic DNAs were performed as described previously (53) The sequences of the primers used for real-time qPCR and reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used for real-time qPCR and RT-PCR

| Primer | Direction | 5′→3′ |

|---|---|---|

| ChIP | ||

| vIRF3 | Forward | GATAGTGATCCGAGTCATAT |

| Reverse | GCCACGAGATCCAACAAGCT | |

| OriLytR | Forward | TACGTGTAAATCCAAGAGAT |

| Reverse | TAGGTCCACGCTCACCTCTG | |

| LANApr | Forward | CTTAACACAAATCATGTACA |

| Reverse | GCAGCTTGGTCCGGCTGACT | |

| RTAup | Forward | CGGCTTACCGACAGTTCTTT |

| Reverse | GAGTATGGCGGACTGTCACC | |

| RTApr | Forward | AAAGTCAACCTTACTCCGCAAG |

| Reverse | GCTGCCTGGACAGTATTCTCAC | |

| RTAdw | Forward | TTGCCAAGTTTGTACAACTGCT |

| Reverse | ACCTTGCAAAGACCATTCAGAT | |

| ORF10pr | Forward | CTCTTGCGCTATGTGGGACAA |

| Reverse | GGCAGTTAGACACCGTTATCT | |

| ORF11pr | Forward | GGCACCCATACAGCTTCTACGA |

| Reverse | CGTTTACTACTGCACACTGCA | |

| K2pr | Forward | ATCCAATTGAGTCTCTGAATGA |

| Reverse | CCTTCAGTGAGACTTCGTAACT | |

| ORF2pr | Forward | ACACAGTAAAGTGTAGGATC |

| Reverse | TCTAGTTGATATCCTTCCACA | |

| K3pr | Forward | CTAGAGATAGTGAGCCAGGT |

| Reverse | CTGGTACGGTCACTTGTTGCA | |

| ORF70pr | Forward | AGTTACCTCATGCTGAATCGA |

| Reverse | ACAAACTTCCAGGATCTATCA | |

| OriLytpr | Forward | TCCTCGTTACGGGTAAATCCA |

| Reverse | ACCCCTTCGCCGGGAACGCTA | |

| K5pr | Forward | CTACATATCCAGCAGATGGGT |

| Reverse | GTGAATACGTTAGACATCTGT | |

| K6pr | Forward | ACCGCATGCGTTCCAGTCGGT |

| Reverse | TGGTACACTGATCGCCAGAT | |

| K7pr | Forward | TGAAGGATGATGTTAATGACA |

| Reverse | GAAGCGGCAGCCAAGGTGACT | |

| ORF25pr | Forward | AGTTGTCGGTGTCTATCTGT |

| Reverse | TGCAGAGCGATACGCAGACT | |

| PABPCpr | Forward | TCCGAAACGTGCGTAGATGGA |

| Reverse | CAGCCAGTTGGTGTCAGCGA | |

| ACTpr | Forward | CCACAGCCAGAGGTCCTCAG |

| Reverse | AGGAGCTCTTGGAGGGCATG | |

| JunBpr | Forward | GGCTGGGACCTTGAGAGC |

| Reverse | GTGCGCAAAAGCCCTGTC | |

| JunBdw | Forward | GACTACAAACTCCTGAAACCGAGC |

| Reverse | CGAGCTTGAGAGACGCGCCGGTGT | |

| LANAdw | Forward | GAGTCTGGTGACGACTTGGAG |

| Reverse | AGGAAGGCCAGACTCTTCAAC | |

| K5dw | Forward | GAGCAGTTAGGATGACCAGGAGCGT |

| Reverse | GTGGCGTAGTCGCCTTAACCTGTG | |

| K6dw | Forward | CTATTAGGCGTGTACGACACGAGT |

| Reverse | GGCGTTACATCTGACAGAACAGA | |

| K7dw | Forward | TCGGCTAGGTTTTCCGTCCTACT |

| Reverse | ATCCAATGCAATAACCCGCAAGG | |

| RT-PCR | ||

| LANA | Forward | GAGTCTGGTGACGACTTGGAG |

| Reverse | AGGAAGGCCAGACTCTTCAAC | |

| RTA | Forward | TTGCCAAGTTTGTACAACTGCT |

| Reverse | ACCTTGCAAAGACCATTCAGAT | |

| K8 | Forward | GGTCTGTGAAACGGTCATTGA |

| Reverse | TCTATGTAGTCGCCTCTTGGA | |

| ORF48 | Forward | CCACATCTTCATAGAGCACAT |

| Reverse | ATTGCATCACCAGGGTATCCA | |

| OriLyt | Forward | TCCTCGTTACGGGTAAATCCA |

| Reverse | ACCCCTTCGCCGGGAACGCTA | |

| K5 | Forward | TAAGCACTTGGCTAACAGTGT |

| Reverse | GGCCACAGGTTAAGGCGACT | |

| K6 | Forward | ATGCTGCGTTAGCGTACTGCT |

| Reverse | GAACCCGTAGCAGCAGCTAT | |

| K7 | Forward | TATGGGAACACTGGAGATAA |

| Reverse | AGCGGCAAGAAGGCAAGCAG | |

| K2 | Forward | TCACTGCGGGTTAATAGGATTT |

| Reverse | CATGACGTCCACGTTTATCACT | |

| ORF70 | Forward | ATGCAGGCCAGGTATAGTCT |

| Reverse | TCCCATATCTTGACTCCTGT | |

| ORF56 | Forward | CACAGATTCCCGTCAATACAAA |

| Reverse | GTATCTTCAGTAGGCGGCAGAG | |

| ORF57 | Forward | AGGGATATCACCGCTCTCATAAGA |

| Reverse | CTGCGGTTTCTCGACGGCAACTCA | |

| ORF59 | Forward | AACCGCAGTTCGTCAGGACCACCA |

| Reverse | CCTTAGCCACTTAAGTAGGAATG | |

| JunB | Forward | CACCAAGTGCCGGAAGCGGA |

| Reverse | AGGGGCAGGGGACGTTCAGA |

IF analysis.

BCBL-1 cells were fixed on a coverslip by 10% poly-l-lysine (Sigma, P8920) per immunofluorescence (IF). Immunofluorescent detection of KSHV proteins in BCBL-1 cells was performed after cross-linking the cells with 3% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, permeabilizing them with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min, and staining them with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)- or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-coupled secondary antibodies for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were washed with PBS, dried, fixed onto slides with Dako fluorescent mounting medium, and finally analyzed by confocal microscopy. Nuclei were also visualized with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). The cells with detectable lytic protein expression (RTA, open reading frame 59 [ORF59], K5, K2, K9, or K8.1) were further analyzed by manual classification. Based on their fluorescent signal(s), approximately 60 to 80 lytic protein-expressing cells/samples were assigned to one of three categories: RTA expression alone, lytic protein expression (ORF59, K5, K2, K9, or K8.1) in the absence of RTA, or coexpression of RTA with one of the lytic proteins. The proportion of cells in each category was calculated as a percentage of the total number of lytic protein-positive cells.

KSHV production, infection, and flow cytometry.

iSLKBAC16 and iSLKBAC16RTAstop cells were treated with 1 μg/ml of doxycycline (Dox) and 1 mM sodium butyrate (NaB) for 3 days. The virus-containing supernatant was cleared of cell debris by centrifugation at 2,000 rpm for 10 min, passed through a 0.45-μm-pore filter, and used to infect 293T cells by centrifugation (2,000 × g) for 45 min at 30°C. At 24 h postinfection, the numbers of infected cells (based on green fluorescent protein [GFP] signal) were determined by flow cytometry (FACS CantoII; BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA). Infectious units are expressed as the number of GFP-positive cells in each well that was calculated from the total cell number/well at the time of analysis.

Construction of an RTA-deficient KSHV (BAC16RTAstop).

The RTA-deficient KSHV was generated by changing the 16th and 17th amino acids of the coding sequence of RTA GAAAGC to GGCTAGC, resulting in a Stop codon and a new NheI restriction enzyme site in the second exon of the RTA gene in bacterial artificial chromosome 16 (BAC16). The mutagenesis was performed in the GS1783 Escherichia coli strain by using “en passant” mutagenesis, as described previously (52). The RTAstop mutant was generated by amplifying a Kanr/I-SceI cassette from the pEP-Kan-S plasmid using the following primers: forward primer 5′-CTCTCTCCTTAGGGTAAGAAGCTTCGGCGGTCCTGTGTGGGCTAGCTTCGTCGGCCTCTCaggatgacgacgataagtaggg and reverse primer 5′-GTAGAGTTGGGCCTTCAGTTCGTCCGAGAGGCCGACGAAGCTAGCCCACACAGGACCGCCaaccaattaaccaattctgattag. Uppercase letters indicate KSHV genomic sequences that were used for homologous recombination, whereas the sequences given in lowercase letters were used to PCR amplify the Kanr/I-SceI cassette from the pEP-Kan-S plasmid. AseI and NheI restriction enzyme digestions of BAC DNAs followed by either conventional agarose gel electrophoresis or pulsed-field gel electrophoresis were used to verify that there were no genetic rearrangements in the BAC16RTAstop mutant compared to wild-type (WT) BAC16. In addition, colony PCR and direct sequencing were also performed to verify the correct sequence of BAC16RTAstop mutants.

RESULTS

Stalled RNAPII at the promoters of a group of lytic genes during latency.

Given that the H3K4me3 and acetylated histone H3-activating histone modifications were found on the promoters of several repressed lytic genes during latency (23, 53), we determined the status of their transcription by detecting RNAPII occupancy. To perform RNAPII ChIP assays, we extracted chromatins from both uninduced (latency) and Dox-induced (8 h, reactivation) TREXBCBL1-Rta cells. DNAs purified from the RNAPII ChIPs were labeled and hybridized to our custom-designed KSHV-specific 15-bp-tiling microarray (53). In agreement with the constitutive expression of latent genes (vIRF3 and LANA), RNAPII was readily detected at their promoter regions during latency (Fig. 1A). Unexpectedly, the RNAPII occupancy was apparently present at the promoter regions of OriLytL (origin of lytic replication on the left side of the viral genome), K5, K6, and K7 lytic genes during latency, while it was nearly absent from the rest of the viral genome (Fig. 1A and B). Reactivation of the KSHV lytic program was triggered by Dox-inducible RTA for 8 h, enough time for the expression of immediate-early (IE) and early (E) but not late (L) genes (23, 53). Under these conditions, RNAPII was recruited to the genomic regions of the KSHV IE and E genes, whereas the L-gene-rich genomic regions of KSHV were devoid of RNAPII but associated with heterochromatin (Fig. 1A) (53). These results were further confirmed by independent RNAPII ChIP experiments using viral gene promoter-specific real-time qPCRs (Fig. 1C).

Fig 1.

Binding of RNA polymerase II on the KSHV genome. (A) Genome-wide mapping of RNAPII on the KSHV genome during latency and reactivation using the ChIP-chip assay. H-224 RNAPII antibody was used for chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with the lysates of uninduced (latency) and reactivated (by 8 h of stimulation with 1 μg/ml doxycycline) TRExBCBL1-Rta cells. Missing probes in specific genomic regions that contain highly repetitive sequences are shown below the graph of the KSHV genome (**). The alternating dark and light blue squares represent viral ORFs. (B) Schematic representation of the promoters of OriLytL-K7/PAN genes showing their known regulatory elements and the relative positions of RNAPII during latency. (C) RNAPII ChIPs. ChIP DNA was measured by real-time qPCRs using primers for the latent promoters (La) and the selected early or late (L) promoters. PABPC was used as a cellular control, representing a constitutively active cellular promoter. RTAup, RTApr, and RTAdw represent the upstream promoter region of RTA, the transcription start site of RTA, and the downstream portion of the RTA promoter within the gene body, respectively. (D) ChIP analysis of the serine 5 phosphorylated RNAPII (pS5 RNAPII) and (E) the serine 2 phosphorylated RNAPII (pS2 RNAPII) in latent and reactivated TRExBCBL1-Rta cells. (F and G) ChIP assays for the total RNAPII (F) and the serine 5 phosphorylated RNAPII (pS5 RNAPII) (G) using uninduced KSHV-infected BC1 and VG1 cells.

Next, we determined whether the RNAPII on the promoters of OriLytL, K5, K6, and K7 lytic genes was transcriptionally active or stalled. Hyperphosphorylation of the serine 5 residue (S5) and hypophosphorylation of the serine 2 (S2) at the C-terminal domain (CTD) of the large subunit of RNAPII are hallmarks of stalled RNAPII, whereas the hyperphosphorylation of S2 concomitantly with the hyperphosphorylated S5 is the marker for fully engaged RNAPII in transcription elongation (5). Our ChIP data showed that the hyperphosphorylation of S5, but not the hyperphosphorylation of S2, of RNAPII was detected at the promoters of K5, K6, and K7 lytic genes, suggesting stalled RNAPII, whereas the hyperphosphorylated S2 of RNAPII was enriched primarily at the active latent promoters during latency (Fig. 1D and E). In contrast, the lytic reactivation of KSHV increased the overall CTD phosphorylation of RNAPII at IE and E genes, but not at L genes such as ORF25 and ORF64 (Fig. 1A, D, and E). The similar levels of RNAPII binding on the cellular PABPC promoter indicated that the efficacies of ChIPs were similar between uninduced and Dox-induced samples and that the increase of RNAPII binding and its S2 or S5 hyperphosphorylations were specific for the KSHV genome under viral reactivation conditions (Fig. 1C to E). Finally, we further showed that the binding of hyperphosphorylated S5 RNAPII to the promoters of the OriLytL, K5, K6, and K7 genes during latency was not restricted to BCBL-1 as it was detected in BC1 and VG1 KSHV-positive PEL cells as well (Fig. 1F and G). In summary, these data demonstrate that while there is transcriptionally active RNAPII on the constitutively active promoters of latent genes, the promoters of a specific group of KSHV lytic genes are occupied with stalled RNAPII during latency.

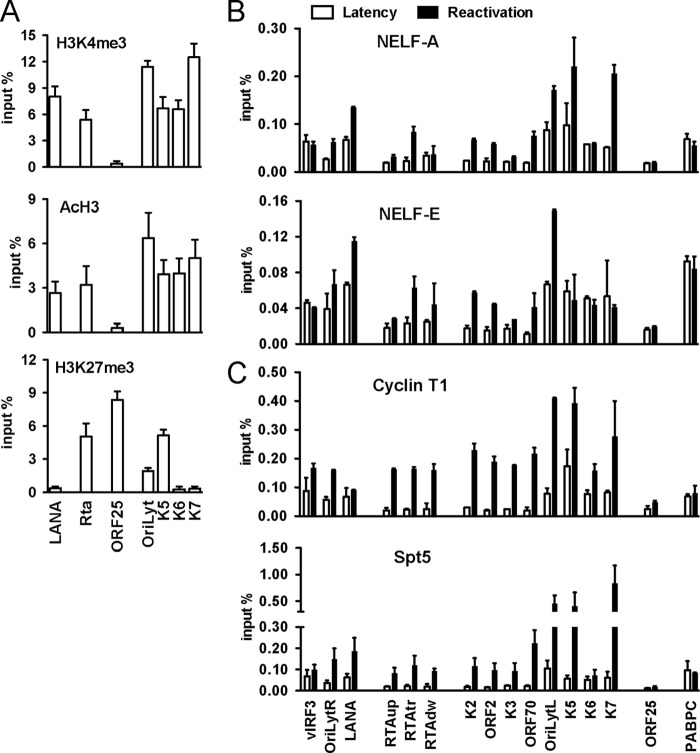

The promoters of OriLyt, K5, K6, and K7 are occupied by transcription elongation factors.

A number of studies showed that the transition from paused RNAPII to transcriptional elongation is controlled by the interactions of negative and positive transcription elongation factors with RNAPII at the promoter-proximal region (39). Given that RNAPII-mediated transcription was stalled at the activating histone mark-enriched promoter regions of OriLytL, K5, K6, and K7 (Fig. 2A), we tested whether transcription elongation factors such as NELF, DSIF, and P-TEFb were also recruited to these promoters. Using ChIP assays, we assessed the presence of the NELF complex (NELF-A and NELF-E subunits), Spt5 (DSIF), and cyclin T1 (P-TEFb) at these lytic promoters (Fig. 2B and C). This showed that both the negative (NELF and DSIF) and the positive (P-TEFb) transcription elongation factors were apparently present on the promoters of the OriLytL, K5, K6, and K7 lytic genes and the promoters of the latent genes (vIRF3 and LANA) during latency (Fig. 2B and C, white bars). Upon reactivation, however, their recruitment was readily increased in most of the tested viral promoters, which was coincident with the increased binding activity of hyperphosphorylated S2 RNAPII (Fig. 1D and 2B and C, black bars).

Fig 2.

Dynamic association of transcription elongation factors with viral promoters during latency and reactivation. ChIP experiments were done as described in the legend to Fig. 1. (A) The enrichment of activating (H3K4me3, AcH3) and repressive (H3K27me3) histone modifications on the promoters of the LANA latent gene, the RTA immediate-early (IE) gene, the OriLytL, K5, K6, and K7 early (E) genes, and the ORF25 late (L) gene during latency. (B) Recruitment of NELF-A and NELF-E on viral promoters during latency and upon lytic reactivation of KSHV. (B) Binding of cyclin T1 and Spt5 to viral promoters.

Depletion of the NELF genes preferentially induces expression of the viral lytic genes that have RNAPII on their promoters during latency.

The NELF complex has been shown to be a key factor in the inhibition of transcription at several cellular and viral genes, such as heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70), JunB, or HIV genes (20). Interestingly, RNAPII and NELF co-occupied the promoter regions of the OriLytL, K5, K6, and K7 lytic genes during latency (Fig. 1 and 2). To test the hypothesis that the OriLytL, K5, K6, and K7 lytic genes were repressed by the NELF complex, we performed specific shRNA-mediated depletion (shNELF) of NELF-A and NELF-E, subunits that are required for the stability of the NELF complex formation and essential for NELF/DSIF-mediated RNAPII pausing (38, 62). Immunoblot analysis indicated that the levels of all NELF subunits were efficiently reduced in shNELF-treated cells compared to scrambled shRNA-transduced cells (shcontrol), while the levels of Spt5, CDK9, and cyclin T1 were not affected (Fig. 3A). RT-PCR analysis revealed that NELF depletion resulted in the efficient induction of OriLytL, K5, K6, and K7 gene expression as well as cellular JunB gene expression, but not of immediate-early genes (RTA, ORF48 and ORF45) or the latent gene (LANA) (Fig. 3B). Increased K5 expression in shNELF-treated BCBL-1 cells was further confirmed by immunoblotting and immunofluorescence analyses (Fig. 3C and D). Furthermore, NELF expression was depleted in 293T cells carrying rKSHV.219, which contains a constitutively expressing GFP gene as an infection marker and an RTA-inducible-PAN promoter-controlled red fluorescent protein (RFP) gene as a reactivation marker (54). As seen in BCBL-1 cells, the K5 gene expression was robustly induced in shNELF-treated 293T-rKSHV.219 cells, whereas neither the LANA/RTA gene expression nor the RFP expression was increased under the same conditions (Fig. 3E and F). These results strongly indicate that the NELF complex is specifically involved in the repression of the OriLytL, K5, K6, and K7 lytic genes, whose promoters are heavily occupied by RNAPII during latency.

Fig 3.

Depletion of NELF genes induces the expression of viral lytic genes that possess RNAPII on their promoters during latency. (A) NELF gene depletion. BCBL-1 cells were transduced by lentiviruses carrying either scrambled shRNA (shcontrol) or NELF-A- and NELF-E-specific shRNAs (shNELF). At 3 days postinfection, whole-cell lysates were used for immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (B and C) RT-PCR (B) and immunoblotting (C) analysis of viral gene expression. Total RNAs were purified from mock-treated, shcontrol lentivirus-infected or shNELF lentivirus-infected BCBL-1 cells. TERxBCBL1-Rta cells induced with doxycycline for 24 h (TREX24) were included as controls. Semiquantitative RT-PCR analyses (B) and immunoblotting (C) were performed for the indicated viral genes. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and JunB (B) as well as actin (C) were included as cellular controls. (D) Immunofluorescent detection of K5 (green) and RTA (red) expression in lentiviral shcontrol or lentiviral shNELF-transduced BCBL-1 cells. The nucleus was counterstained with DAPI. (E) Immunoblotting analysis of viral protein expression. At 3 days postinfection with shcontrol or shNELF lentivirus, 293T-rKSHV.219 cell lysates were used for immunoblotting analysis. TREX24 cell lysates were used as controls for RTA expression. (F) RFP expression in lentiviral shcontrol- or lentiviral shNELF-transduced 293T-rKSHV.219 cells. The RFP expression of rKSHV.219 virus is controlled by the RTA-inducible PAN lytic promoter, whereas GFP is constitutively expressed from the EF-1 cellular promoter.

NELF depletion releases the transcriptional elongation block at the promoter-proximal regions of specific KSHV lytic genes.

To investigate whether the NELF complex indeed prevents the transition of RNAPII to transcriptional elongation at the OriLytL, K5, K6, and K7 lytic genes during latency, we performed a ChIP assay to measure the effect of NELF gene depletion on the levels of total RNAPII, phosphorylated S5 RNAPII, phosphorylated S2 RNAPII, and Spt5 at the OriLytL-K7 genes during latency (Fig. 4). The hyperphosphorylated S5 RNAPII is a marker of active RNAPII, the hyperphosphorylated S2 RNAPII is characteristic of the elongation-competent form, and Spt5 is a transcription elongation factor that remains associated with RNAPII as it transcribes target genes (48). ChIP signals were measured at the promoter-proximal regions (pr) and the downstream regions (dw) within the 5′ regions of viral LANA and OriLyt-K7 gene bodies. A cellular JunB gene whose expression is repressed by the NELF (20) was included as a positive control. These experiments revealed that depletion of the NELF expression led to the increases of the enrichment and phosphorylations of RNAPII at the viral OriLytL-K7 gene and cellular JunB gene, but not at the LANA gene (Fig. 4). In agreement with the role of the NELF complex in pausing RNAPII transcription activity, depletion of NELF expression resulted in the increased hyperphosphorylation of the CTD serine 5 of RNAPII (pS5 RNAPII) without significantly affecting the total level of RNAPII at the promoter-proximal region of OriLytL-K7 genes. On the other hand, the hyperphosphorylation of the CTD serine 2 of RNAPII (pS2 RNAPII) was increased within the OriLytL-K7 gene bodies (Fig. 4). In addition, the recruitment of Spt5 was concomitant with the increased level of pS2 RNAPII downstream of these genes (Fig. 4). Taken together, these results suggest that the host NELF complex inhibits transcription elongation at the OriLytL, K5, K6, and K7 lytic genes whose promoters are occupied by stalled RNAPII during latency, while NELF-specific gene knockdown releases its elongation block, allowing transcription of the OriLytL, K5, K6, and K7 lytic genes.

Fig 4.

NELF-mediated RNAPII stalling at the OriLyt-K7 lyitc promoters. ChIP assays were performed with lentiviral shcontrol- or lentiviral shNELF-infected BCBL-1 cells using antibodies of total RNAPII (N20), serine 5 phosphorylated RNAPII (pS5 RNAPII), serine 2 phosphorylated RNAPII (pS2 RNAPII), and the transcription elongation factor Spt5.

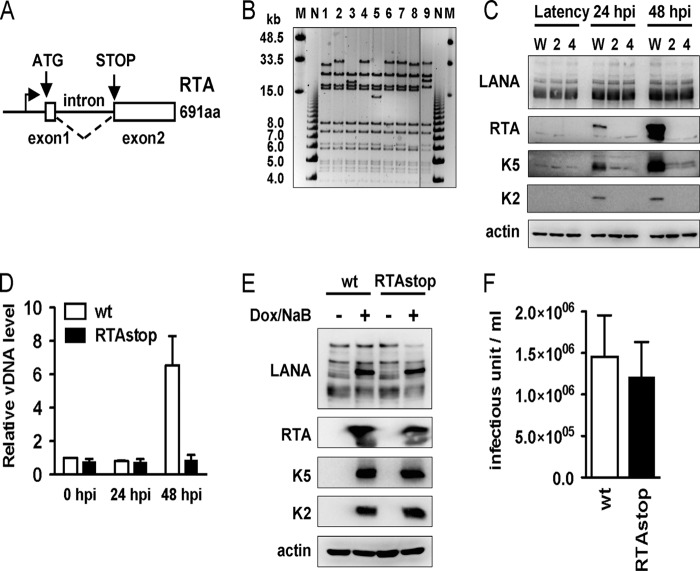

RTA-independent induction of KSHV lytic gene expression.

Since depletion of the negative elongation factor activity leads to the induction of OriLyt, K5, K6, and K7 lytic gene expression in an RTA-independent manner, we hypothesized that the promoters of the OriLyt, K5, K6, and K7 lytic genes with stalled RNAPII during latency were poised to be more robustly activated in response to external signaling pathways than those of other lytic genes without stalled RNAPII. To test this hypothesis and to exclude the effect of RTA on the induction of lytic gene expression, we constructed an RTA-deficient recombinant KSHV. Specifically, a frameshift mutation followed by a Stop codon was inserted into the beginning of the second exon of RTA to eliminate RTA protein expression (Fig. 5A). En passant mutagenesis was performed using a new GFP-expressing BAC clone of KSHV, called BAC16, that is capable of producing infectious recombinant viruses, as shown in the accompanying article by Brulois et al. (5a). Several mutant clones were isolated and tested by NheI restriction enzyme digestion, followed by DNA sequencing of the mutation sites. Figure 5B shows a representative NheI digestion of the mutant clones (lanes 1 to 8) compared to wild-type BAC16 (lane 9). The insertion of an additional NheI site overlapping with the Stop codon in BAC16 enabled us to distinguish the mutants from the wild-type BAC16. Based on the digestion patterns and DNA sequencing results, we chose clones 2 and 4 for further analysis to test the correct Stop codon insertion without any detectable genomic rearrangements (Fig. 5B). Next, the wild-type and RTAstop mutant (clones 2 and 4) BAC DNAs purified from E. coli were transfected into 293T cells, followed by selection for hygromycin resistance (Hygr). Then, Hygr cell lines were treated with 3 mM sodium-butyrate (NaB) for 24 and 48 h to induce viral lytic replication. Immunoblotting showed that despite the absence of other lytic gene expression and viral DNA replication, K5 expression was readily detected in the RTAstop KSHV-stable cells (Fig. 5C and D). In contrast, the levels of expression of the latent gene, coding for LANA, were comparable in both the wild-type and RTAstop KSHV-infected cells (Fig. 5D). To further demonstrate that the deficiency of lytic replication of the RTAstop KSHV was due to the lack of RTA expression and not any unintentional genetic defects that may have arisen during the construction of RTAstop KSHV, we introduced WT and RTAstop BAC16 (clone 4) into a recombinant SLK cell line, iSLK, which has been engineered to express RTA in a doxycycline (Dox)-inducible manner (36). Immunoblot analysis showed comparable levels of expression of the K5 and K2 lytic genes in the iSLK-BAC16 and iSLK-BAC16RTAstop cell lines upon Dox-induced lytic reactivation (Fig. 5E). The supernatants from iSLK-BAC16 and iSLK-BAC16RTAstop cell lines showed comparable virus titers (Fig. 5F), indicating that the complementation of RTA expression is sufficient to fully induce lytic reactivation of RTAstop KSHV.

Fig 5.

Construction of an RTA-deficient KSHV. (A) Schematic diagram of the RTA gene. The frameshift/Stop mutation was introduced into the second exon of RTA. (B) NheI restriction enzyme digestion of BAC16RTAstop mutant bacmids (lanes 1 to 8) and wild-type BAC16 (lane 9). Lanes M and N indicate the midrange PFGE DNA marker and the 1-kb DNA marker, respectively. (C) Expression of viral proteins in 293TBAC16 (W) and 293TBAC16-RTAstop (carrying either BAC16RTAstop bacmid clone 2 or 4) cell lines. Lysates of uninduced cells (Latency) or cells induced with 3 mM NaB for 24 or 48 h were used for the immunoblotting assay with antibodies to the indicated proteins. (D) Viral genomic DNA copy number. Genomic DNA was prepared from 293TBAC16 (wt) and 293TBAC16RTAstop (clone 4, RTAstop) either mock treated (0 hpi) or treated with 3 mM NaB (24 and 48 hpi). The levels of viral genomic DNA were determined by real-time qPCR and were calculated relative to the mock-treated samples (0 hpi). (E) Immunoblot analysis of viral protein expression. Lysates of iSLKBAC16 (wt) or iSLKBAC16RTAstop (clone 4) cells either mock treated (−) or treated with 1 μg/ml of doxycycline and 3 mM NaB (+) were used for immunoblotting assays with antibodies to the indicated proteins. (F) Comparison of infectious virus production. iSLKBAC16 (wt) and iSLKBAC16RTAstop (clone 4) cells were induced with 1 μg/ml of doxycycline and 3 mM NaB for 3 days. Virus titers were determined by infecting 293T cells and quantifying the numbers of GFP-expressing cells by flow cytometry at 24 h postinfection.

While K5 expression was readily detectable in 293T-BAC16RTAstop cells during latency, it was further enhanced by the shRNA-mediated depletion of NELF gene expression (Fig. 6A). This finding was additionally corroborated by immunofluorescence analysis of 293T cells infected by BAC16 or BAC16RTAstop (clone 4) (Fig. 6B). Strikingly, treatment of 293T-BAC16RTAstop with 3 mM NaB was still able to induce lytic gene expressions to certain extents; specifically, the levels of induction of immediate-early RTA, K8, and ORF48 gene expression were comparable between 293T-BAC16 and 293T-BAC16RTAstop cells (Fig. 6C). In contrast, the K5, K6, and K7 lytic genes carrying stalled RNAPII on their promoters during latency were induced more robustly than those lytic genes (RTA, K2, K8, ORF48, ORF57, and ORF70) lacking RNAPII on their promoters during latency (Fig. 6C). These results indicate that the promoters of OriLyt, K5, K6, and K7 lytic genes with stalled RNAPII during latency are poised for more robust induction in response to external signaling pathways than those of other lytic genes without stalled RNAPII.

Fig 6.

RTA-independent KSHV lytic gene expression. (A) Viral protein expression. At 72 h postinfection with shcontrol or shNELF lentivirus, the immunoblotting assay was performed using lysates from infected 293TBAC16RTAstop (clone 4) cells with the indicated antibodies. (B) Immunofluorescence analysis of the KSHV lytic protein K5 in lentivirus shcontrol- or shNELF-transduced 293TBAC16 and 293TBAC16RTAstop (clone 4) cells. DAPI staining shows the nuclei. (C) Real-time qPCR analysis of KSHV viral gene expression. At 8, 24, and 48 h poststimulation of 293TBAC16 or 293TBAC16RTAstop (clone 4) cells with 3 mM NaB, KSHV gene expression was determined by real-time qPCR. The induction levels of viral gene expression were calculated relative to that of mock-treated cells.

We also tested the unique characteristics of the K5 expression profile in KSHV-infected PEL cells using immunofluorescence analyses. As seen with a majority of latently infected PEL cells, of which a small population (less than 3 to 5%) shows spontaneous KSHV lytic gene expression (31), a few latently infected PEL cells showed the expression of RTA, K2, K5, K8, K8.1, K9, and/or ORF59 (Fig. 7). Intriguingly, a large portion of K5-positive PEL cells was RTA negative, whereas a majority of ORF59-postive PEL cells were RTA positive (Fig. 7A, B, and C). However, upon NaB stimulation, nearly all K5-positive or ORF59-positive PEL cells were RTA positive (Fig. 7A and B). When the proportion of lytic-protein-positive PEL cells showing RTA-positive and/or -negative expression was calculated as a percent distribution, it further confirmed that a larger portion of the K5-positive cells was RTA negative compared to other lytic-gene-expressing cells (Fig. 7C). These data showed that K5 gene expression is more frequently RTA independent than the expression of other lytic genes.

Fig 7.

Immunofluorescence analysis of lytic protein expression in BCBL-1 cells. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis of K5 and RTA expression. Mock-treated (latent cycle) or NaB-treated BCBL-1 (lytic cycle) cells were permeabilized and costained with anti-K5 mouse monoclonal and anti-RTA rabbit polyclonal antibodies, followed by staining with FITC-coupled anti-mouse and TRITC-coupled anti-rabbit secondary antibodies, respectively. (B) Immunofluorescence analysis of ORF59 and RTA expression. Mock-treated or NaB-treated BCBL-1 cells were permeabilized and costained with anti-ORF59 mouse monoclonal and anti-RTA rabbit polyclonal antibody, followed by staining with FITC-coupled anti-mouse and TRITC-coupled anti-rabbit secondary antibody. (C) Ratio of BCBL-1 cells expressing lytic protein alone (viral protein indicated below the graph), RTA alone, or both RTA and lytic protein. For details of the percent calculation, see Materials and Methods.

DISCUSSION

Transcription elongation has emerged as a critical regulatory step for both cellular and viral gene expression (9, 30, 48, 65, 70). In the present study, we showed that RNAPII transcription elongation was paused at the promoters of KSHV OriLytL, K5, K6, and K7 lytic genes (OriLytL-K7 genes) during latency and was regulated by the cellular negative elongation factor (NELF) complex. In addition, we found that the expression of K5, K6, and K7 lytic genes carrying paused RNAPII on their promoters during latency was induced more robustly upon external stimulus than that of other lytic genes without paused RNAPII. Furthermore, the depletion of NELF gene expression in PEL cells or in KSHV-infected 293T cells resulted in the upregulation of OriLytL-K7 gene expression in an RTA-independent manner. These data indicate that the RNAPII transcription elongation of the KSHV OriLytL-K7 lytic promoters is inhibited by NELF during latency, which can be resumed upon external stimuli in an RTA-independent manner.

Besides the promoters of LANA and vIRF3 latent genes as well as those of OriLytL-K7 lytic genes, the RTA promoter region was also enriched with activating histone marks but devoid of RNAPII during latency. RTA is the first viral gene to be activated during lytic reactivation, and its promoter is associated with bivalent chromatin (23, 53). Bivalent chromatin is frequently accompanied by stalled RNAPII on the promoters of highly inducible cellular genes whose transcription is poised in the basal state for rapid activation upon specific stimuli (4, 46). It is possible that the absence of RNAPII on the bivalent RTA promoter during latency may be critical to avoid the unwanted activation of RTA expression upon stochastic fluctuation in cell signaling, which potentially compromises the maintenance of latency. Upon adequate stimulation, however, RTA expression triggers a temporally ordered expression cascade of lytic genes (37). Our ChIP data also showed that at the early phase of KSHV reactivation, RNAPII was recruited primarily to the genomic regions mostly encoding immediate-early and early genes, while the late-gene-rich regions were essentially RNAPII free (Fig. 1A). This is consistent with our previous findings that heterochromatin is associated with most of the late genes during the early phase of reactivation, which is known to be unfavorable for RNAPII binding (53).

The OriLytL promoter seems to be unique among the repressed lytic promoters as the total RNAPII level was the highest at this promoter region on the KSHV genome during latency, which was also accompanied by higher RNAPII pS2 phosphorylation relative to other viral promoters. It is conceivable that transcription may be initiated from the OriLyt promoter but terminated shortly within the repetitive sequence of OriLytL. Since the specific OrLytL primers just downstream of this repetitive sequence were used for the RT-PCR assay, we could not detect short noncoding RNAs even if they were transcribed (Fig. 3B). Along with this, the recruitment of large amounts of RNAPII onto viral promoters during reactivation was also accompanied by the increased NELF complex on the KSHV genome. A number of studies have shown that NELF is involved in the regulation of the RNAPII-mediated transcription rate where NELF-mediated RNAPII pausing acts as a transient checkpoint during the transcription cycle. On the other hand, several studies have also shown the positive action of NELF such that binding of NELF to RNAPII enhances the induction of transcription on chromatinized DNA (2, 19). Thus, the dual functions of NELF-mediated regulation of RNAPII activity may potentially contribute to the increased recruitment of NELF during KSHV reactivation.

Although the promoter regions of both the OriLytL-K7 lytic genes and the LANA and vIRF3 latent genes possessed activating histone marks and RNAPII with transcription elongation factors (P-TEFb and DSIF), only the expression of OriLytL-K7 genes was repressed during latency. This may be due to the recruitment of enzymatically inactive P-TEFb to the promoters of the K5 to K7 genes, resulting in the hypophosphorylated S2 RNAPII at the K5 to K7 genes (Fig. 1D and E). In contrast, the promoters of LANA and vIRF3 latent genes were associated with the hyperphosphorylated S2 RNAPII, indicating the recruitment of active P-TEFb that allows the constitutive expression of latent genes (Fig. 1D and E). The transition of P-TEFb between enzymatically active and inactive forms is regulated by the dynamic association of cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (CDK9), the kinase subunit of P-TEFb, with nuclear repressors (40, 67, 68). CDK9 is released from its inactive complex when cells are exposed to hypertrophic or stress signals, and subsequently various transcription factors (e.g., Brd4, c-myc, NF-κB, Tat, and VP16) recruit P-TEFb to the target promoters (32, 34, 45, 47, 59, 66). Investigation of HIV-1 transcription has recently revealed that a catalytically inactive P-TEFb is recruited to the HIV-1 promoter during viral latency, which is incompatible with transcription elongation. However, subsequent binding of the HIV transcription factor Tat to the HIV-1 promoter disrupts the inactive P-TEFb and recruits an enzymatically active CDK9 to resume transcription (14). It is possible that RTA-independent KSHV gene expression may occur via specific cellular transcription factors involved in the host's signal-dependent gene expression regulation circuits that have been shown to be crucial for cellular gene expression in response to environmental stresses (1, 18, 25, 49).

Transcription factors that regulate the promoter activity of OriLytL-K7 lytic genes in the context of the chromatinized viral genome are largely unknown (16, 24, 50, 58). While RTA is the key viral transcription factor to activate these lytic promoters (37), the presence of latency-associated stalled RNAPII on their promoters implies that the OriLytL-K7 lytic genes may also be expressed independently of RTA upon external stimuli. In fact, consistent with previous studies (24, 41), the RTA-independent expression of the K5 gene was detected in a number of latently infected PEL cells and RTA-deficient KSHV-infected 293T cells. We also showed that the expression of K5, K6, and K7 lytic genes was highly inducible upon external stimuli compared to that of other lytic genes, which did not have RNAPII on their promoters during latency. Thus, we speculate that cellular signal transduction is not only partially exchangeable with RTA in regard to the activation of the OriLytL-K7 lytic gene expression but also provides a novel expression profile of KSHV immune deregulatory genes that is likely different from that of the RTA-dependent lytic reproduction program. Importantly, Notch signaling has been shown to be capable of inducing an RTA-independent expression of a set of lytic genes, including the K5, K6, and K7 genes, but the role of Notch signaling in relieving NELF-mediated RNAPII pausing has not been investigated (7).

Latency is a fundamental viral immune evasion strategy, which limits viral antigen expression and thereby prolongs the survival of infected cells. Several KSHV lytic proteins with immune regulatory functions or oncogenic potentials have also been implicated in regulation of viral persistency and pathogenesis (21, 35). It is worth noting that the K5, K6, and K7 lytic proteins have been shown to function in the degradation of surface immune-modulatory receptors, the downregulation of the T-cell response, and the suppression of apoptosis, respectively (12, 13, 26, 57). Therefore, the induction of these lytic genes outside the canonical RTA-mediated lytic reactivation would be beneficial for the protection of latently infected cells against host immune response and apoptosis. In summary, our findings provide new insights into how KSHV lytic genes associated with activating histone marks are repressed during the latent state of infection and how the modulation of RNAPII-mediated transcription elongation triggers the expression of these lytic genes even in the absence of RTA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partly supported by CA082057, CA31363, CA115284, DE019085, AI073099, the Hastings Foundation, and the Fletcher Jones Foundation (J.U.J.).

We thank Yoshihiro Izumiya and Hsing-Jien Kung (UC Davis, Sacramento) for providing the RTA antibody. We are also grateful to Greg Smith (Northwestern University) for the GS1783 E. coli strain. Finally, we thank J. Jung's lab members for discussions.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 June 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Adelman K, et al. 2009. Immediate mediators of the inflammatory response are poised for gene activation through RNA polymerase II stalling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:18207–18212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aida M, et al. 2006. Transcriptional pausing caused by NELF plays a dual role in regulating immediate-early expression of the junB gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:6094–6104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barboric M, Nissen RM, Kanazawa S, Jabrane-Ferrat N, Peterlin BM. 2001. NF-kappaB binds P-TEFb to stimulate transcriptional elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell 8:327–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bernstein BE, et al. 2006. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell 125:315–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brookes E, Pombo A. 2009. Modifications of RNA polymerase II are pivotal in regulating gene expression states. EMBO Rep. 10:1213–1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a. Brulois KF, et al. 2012. Construction and manipulation of a new Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus bacterial artificial chromosome clone. J. Virol. 86:9708–9720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cai Q, Verma SC, Lu J, Robertson ES. 2010. Molecular biology of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and related oncogenesis. Adv. Virus Res. 78:87–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chang H, Dittmer DP, Shin YC, Hong Y, Jung JU. 2005. Role of Notch signal transduction in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus gene expression. J. Virol. 79:14371–14382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chiou CJ, et al. 2002. Patterns of gene expression and a transactivation function exhibited by the vGCR (ORF74) chemokine receptor protein of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 76:3421–3439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cho WK, Jang MK, Huang K, Pise-Masison CA, Brady JN. 2010. Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 Tax protein complexes with P-TEFb and competes for Brd4 and 7SK snRNP/HEXIM1 binding. J. Virol. 84:12801–12809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chopra VS, Hong JW, Levine M. 2009. Regulation of Hox gene activity by transcriptional elongation in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 19:688–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Core LJ, Waterfall JJ, Lis JT. 2008. Nascent RNA sequencing reveals widespread pausing and divergent initiation at human promoters. Science 322:1845–1848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Coscoy L, Ganem D. 2001. A viral protein that selectively downregulates ICAM-1 and B7-2 and modulates T cell costimulation. J. Clin. Invest. 107:1599–1606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dairaghi DJ, Fan RA, McMaster BE, Hanley MR, Schall TJ. 1999. HHV8-encoded vMIP-I selectively engages chemokine receptor CCR8. Agonist and antagonist profiles of viral chemokines. J. Biol. Chem. 274:21569–21574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. D'Orso I, Frankel AD. 2010. RNA-mediated displacement of an inhibitory snRNP complex activates transcription elongation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17:815–821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Durand LO, Advani SJ, Poon AP, Roizman B. 2005. The carboxyl-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II is phosphorylated by a complex containing cdk9 and infected-cell protein 22 of herpes simplex virus 1. J. Virol. 79:6757–6762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ellison TJ, Izumiya Y, Izumiya C, Luciw PA, Kung HJ. 2009. A comprehensive analysis of recruitment and transactivation potential of K-Rta and K-bZIP during reactivation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Virology 387:76–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Feichtinger S, et al. 2011. Recruitment of cyclin-dependent kinase 9 to nuclear compartments during cytomegalovirus late replication: importance of an interaction between viral pUL69 and cyclin T1. J. Gen. Virol. 92:1519–1531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fowler T, Sen R, Roy AL. 2011. Regulation of primary response genes. Mol. Cell 44:348–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gilchrist DA, et al. 2008. NELF-mediated stalling of Pol II can enhance gene expression by blocking promoter-proximal nucleosome assembly. Genes Dev. 22:1921–1933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gilmour DS. 2009. Promoter proximal pausing on genes in metazoans. Chromosoma 118:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Greene W, et al. 2007. Molecular biology of KSHV in relation to AIDS-associated oncogenesis. Cancer Treat Res. 133:69–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guenther MG, Levine SS, Boyer LA, Jaenisch R, Young RA. 2007. A chromatin landmark and transcription initiation at most promoters in human cells. Cell 130:77–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gunther T, Grundhoff A. 2010. The epigenetic landscape of latent Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus genomes. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000935 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haque M, et al. 2000. Identification and analysis of the K5 gene of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 74:2867–2875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hargreaves DC, Horng T, Medzhitov R. 2009. Control of inducible gene expression by signal-dependent transcriptional elongation. Cell 138:129–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ishido S, Wang C, Lee BS, Cohen GB, Jung JU. 2000. Downregulation of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K3 and K5 proteins. J. Virol. 74:5300–5309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jang MK, et al. 2005. The bromodomain protein Brd4 is a positive regulatory component of P-TEFb and stimulates RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription. Mol. Cell 19:523–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kanazawa S, Soucek L, Evan G, Okamoto T, Peterlin BM. 2003. c-Myc recruits P-TEFb for transcription, cellular proliferation and apoptosis. Oncogene 22:5707–5711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kang H, Lieberman PM. 2011. Mechanism of glycyrrhizic acid inhibition of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus: disruption of CTCF-cohesin-mediated RNA polymerase II pausing and sister chromatid cohesion. J. Virol. 85:11159–11169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kapasi AJ, Clark CL, Tran K, Spector DH. 2009. Recruitment of cdk9 to the immediate-early viral transcriptosomes during human cytomegalovirus infection requires efficient binding to cyclin T1, a threshold level of IE2 86, and active transcription. J. Virol. 83:5904–5917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Katano H, Sato Y, Kurata T, Mori S, Sata T. 2000. Expression and localization of human herpesvirus 8-encoded proteins in primary effusion lymphoma, Kaposi's sarcoma, and multicentric Castleman's disease. Virology 269:335–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kurosu T, Peterlin BM. 2004. VP16 and ubiquitin; binding of P-TEFb via its activation domain and ubiquitin facilitates elongation of transcription of target genes. Curr. Biol. 14:1112–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lukac DM, Renne R, Kirshner JR, Ganem D. 1998. Reactivation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection from latency by expression of the ORF 50 transactivator, a homolog of the EBV R protein. Virology 252:304–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Michels AA, Bensaude O. 2008. RNA-driven cyclin-dependent kinase regulation: when CDK9/cyclin T subunits of P-TEFb meet their ribonucleoprotein partners. Biotechnol. J. 3:1022–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moore PS, Chang Y. 2003. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus immunoevasion and tumorigenesis: two sides of the same coin? Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:609–639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Myoung J, Ganem D. 2011. Generation of a doxycycline-inducible KSHV producer cell line of endothelial origin: maintenance of tight latency with efficient reactivation upon induction. J. Virol. Methods 174:12–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nakamura H, et al. 2003. Global changes in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated virus gene expression patterns following expression of a tetracycline-inducible Rta transactivator. J. Virol. 77:4205–4220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Narita T, et al. 2003. Human transcription elongation factor NELF: identification of novel subunits and reconstitution of the functionally active complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:1863–1873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nechaev S, Adelman K. 2011. Pol II waiting in the starting gates: regulating the transition from transcription initiation into productive elongation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1809:34–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nguyen VT, Kiss T, Michels AA, Bensaude O. 2001. 7SK small nuclear RNA binds to and inhibits the activity of CDK9/cyclin T complexes. Nature 414:322–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Okuno T, et al. 2002. Activation of human herpesvirus 8 open reading frame K5 independent of ORF50 expression. Virus Res. 90:77–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ott M, Geyer M, Zhou Q. 2011. The control of HIV transcription: keeping RNA polymerase II on track. Cell Host Microbe 10:426–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Palermo RD, Webb HM, West MJ. 2011. RNA polymerase II stalling promotes nucleosome occlusion and pTEFb recruitment to drive immortalization by Epstein-Barr virus. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002334 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Peng J, Zhu Y, Milton JT, Price DH. 1998. Identification of multiple cyclin subunits of human P-TEFb. Genes Dev. 12:755–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rahl PB, et al. 2010. c-Myc regulates transcriptional pause release. Cell 141:432–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Roh TY, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Zhao K. 2006. The genomic landscape of histone modifications in human T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:15782–15787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sano M, et al. 2002. Activation and function of cyclin T-Cdk9 (positive transcription elongation factor-b) in cardiac muscle-cell hypertrophy. Nat. Med. 8:1310–1317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Selth LA, Sigurdsson S, Svejstrup JQ. 2010. Transcript elongation by RNA polymerase II. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79:271–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Smale ST. 2010. Selective transcription in response to an inflammatory stimulus. Cell 140:833–844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Song MJ, Brown HJ, Wu TT, Sun R. 2001. Transcription activation of polyadenylated nuclear RNA by Rta in human herpesvirus 8/Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 75:3129–3140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sun R, et al. 1998. A viral gene that activates lytic cycle expression of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:10866–10871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tischer BK, Smith GA, Osterrieder N. 2010. En passant mutagenesis: a two step markerless red recombination system. Methods Mol. Biol. 634:421–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Toth Z, et al. 2010. Epigenetic analysis of KSHV latent and lytic genomes. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001013 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Vieira J, O'Hearn PM. 2004. Use of the red fluorescent protein as a marker of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus lytic gene expression. Virology 325:225–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wada T, et al. 1998. DSIF, a novel transcription elongation factor that regulates RNA polymerase II processivity, is composed of human Spt4 and Spt5 homologs. Genes Dev. 12:343–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wada T, Takagi T, Yamaguchi Y, Watanabe D, Handa H. 1998. Evidence that P-TEFb alleviates the negative effect of DSIF on RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription in vitro. EMBO J. 17:7395–7403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wang HW, Sharp TV, Koumi A, Koentges G, Boshoff C. 2002. Characterization of an anti-apoptotic glycoprotein encoded by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus which resembles a spliced variant of human survivin. EMBO J. 21:2602–2615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wang Y, et al. 2004. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus ori-Lyt-dependent DNA replication: cis-acting requirements for replication and ori-Lyt-associated RNA transcription. J. Virol. 78:8615–8629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wei P, Garber ME, Fang SM, Fischer WH, Jones KA. 1998. A novel CDK9-associated C-type cyclin interacts directly with HIV-1 Tat and mediates its high-affinity, loop-specific binding to TAR RNA. Cell 92:451–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wu CH, et al. 2003. NELF and DSIF cause promoter proximal pausing on the hsp70 promoter in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 17:1402–1414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yamada T, et al. 2006. P-TEFb-mediated phosphorylation of hSpt5 C-terminal repeats is critical for processive transcription elongation. Mol. Cell 21:227–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yamaguchi Y, Inukai N, Narita T, Wada T, Handa H. 2002. Evidence that negative elongation factor represses transcription elongation through binding to a DRB sensitivity-inducing factor/RNA polymerase II complex and RNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:2918–2927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yamaguchi Y, et al. 1999. NELF, a multisubunit complex containing RD, cooperates with DSIF to repress RNA polymerase II elongation. Cell 97:41–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yamaguchi Y, Wada T, Handa H. 1998. Interplay between positive and negative elongation factors: drawing a new view of DRB. Genes Cells 3:9–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Yan J, Li Q, Lievens S, Tavernier J, You J. 2010. Abrogation of the Brd4-positive transcription elongation factor B complex by papillomavirus E2 protein contributes to viral oncogene repression. J. Virol. 84:76–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Yang Z, et al. 2005. Recruitment of P-TEFb for stimulation of transcriptional elongation by the bromodomain protein Brd4. Mol. Cell 19:535–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yang Z, Zhu Q, Luo K, Zhou Q. 2001. The 7SK small nuclear RNA inhibits the CDK9/cyclin T1 kinase to control transcription. Nature 414:317–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yik JH, et al. 2003. Inhibition of P-TEFb (CDK9/cyclin T) kinase and RNA polymerase II transcription by the coordinated actions of HEXIM1 and 7SK snRNA. Mol. Cell 12:971–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zhao J, et al. 2007. K13 blocks KSHV lytic replication and deregulates vIL6 and hIL6 expression: a model of lytic replication induced clonal selection in viral oncogenesis. PLoS One 2:e1067 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhou M, et al. 2006. Tax interacts with P-TEFb in a novel manner to stimulate human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 transcription. J. Virol. 80:4781–4791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]