Abstract

Human papillomaviruses (HPV) are composed of the major and minor capsid proteins, L1 and L2, that encapsidate a chromatinized, circular double-stranded DNA genome. At the outset of infection, the interaction of HPV type 16 (HPV16) (pseudo)virions with heparan sulfate proteoglycans triggers a conformational change in L2 that is facilitated by the host cell chaperone cyclophilin B (CyPB). This conformational change results in exposure of the L2 N terminus, which is required for infectious internalization. Following internalization, L2 facilitates egress of the viral genome from acidified endosomes, and the L2/DNA complex accumulates at PML nuclear bodies. We recently described a mutant virus that bypasses the requirement for cell surface CyPB but remains sensitive to cyclosporine for infection, indicating an additional role for CyP following endocytic uptake of virions. We now report that the L1 protein dissociates from the L2/DNA complex following infectious internalization. Inhibition and small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated knockdown of CyPs blocked dissociation of L1 from the L2/DNA complex. In vitro, purified CyPs facilitated the dissociation of L1 pentamers from recombinant HPV11 L1/L2 complexes in a pH-dependent manner. Furthermore, CyPs released L1 capsomeres from partially disassembled HPV16 pseudovirions at slightly acidic pH. Taken together, these data suggest that CyPs mediate the dissociation of HPV L1 and L2 capsid proteins following acidification of endocytic vesicles.

INTRODUCTION

Human papillomaviruses (HPV) comprise a large family of nonenveloped epitheliotropic DNA viruses. Infection with high-risk HPV types, especially HPV type 16 (HPV16) and HPV18, may induce lesions that progress to malignancies, the most common of which is cervical cancer. The viral capsid is composed of 360 copies of the major capsid protein, L1, and up to 72 copies of the minor capsid protein, L2 (1, 4, 8). Seventy-two pentamers of L1, termed capsomeres, are the primary constituents of the outer capsid shell. Capsomeres are linked together by their carboxy-terminal domains and stabilized by intercapsomeric disulfide bonds between highly conserved cysteine residues (39, 53). The L2 protein is inaccessible within the capsid, with the exception of amino acid residues 60 to 120 located near the amino terminus (40). Association of L1 and L2 inside the capsid requires hydrophobic interactions between a small stretch of amino acids close to the carboxy terminus of L2 (residues 390 to 430 for HPV11) and the inner central core of capsomeres (17), similar to the structural interaction determined for VP1 capsomeres and the VP2/VP3 proteins of the related murine polyomavirus (9). In addition, a charge-dependent interaction with L1 has been suggested to require L2 residues 150 to 250 (47).

HPV16 attachment and entry comprise a slow process with half-times of up to 14 h. The prolonged residence of the virus on the cell surface is accompanied by conformational changes affecting both capsid proteins, allowing for sequential engagement of multiple receptors (52). The L1 protein mediates the primary attachment of viral particles to the cell surface (24, 32, 59) and/or extracellular matrix (ECM) of susceptible cells (12), most probably via heparan sulfate (HS) proteoglycans (HSPG) (31). The primary attachment of HPV16 to HS is mediated by surface-exposed lysine residues Lys278 and Lys361 located at the rim of capsomeres (13, 36). In addition to the primary HS attachment site, three additional putative receptor binding sites have been identified by the structural analysis, and two of these seem to be required at postattachment entry steps, possibly mediating multivalent interactions with HS (13). These and other observations (59, 60) suggest that secondary HSPG interactions may play a role in infection. An attachment-induced conformational change in both capsid proteins (15, 60, 69) seems to be required for transfer to a still elusive, putative secondary receptor and infectious internalization (59). HS binding-induced changes in the conformation of the L1 protein are not well defined as yet. However, it appears that HPV16 attachment results in the exposure of the N terminus of L2 protein (15, 49), which contains a neutralizing epitope that cross-reacts with multiple HPV serotypes (50). Accessibility of the L2 amino terminus allows subsequent cleavage of 12 N-terminal amino acids catalyzed by furin convertase on the cell surface, an essential step for infectious internalization (15, 49). HPV16 internalization occurs via a pathway that is independent of caveolin-1 and clathrin (57, 63). Acidification of endosomes (16, 61) as well as transport along microtubules (16, 19, 58, 61) is essential for intracellular trafficking and egress from endosomes of a complex composed of L2 protein and the viral genome. Accumulation of this complex near PML nuclear bodies (PML-NB) additionally requires mitosis (14, 48).

The fate of L1 protein after uncoating has not been studied in detail due to a lack of suitable reagents. However, it is assumed that L1 segregates from the L2/viral genome in an endocytic compartment and is targeted to lysosomes for degradation. Host cell factors involved in uncoating and segregation also have not been identified. We recently demonstrated that an L2 conformational change is mediated by the host cell chaperone cyclophilin B (CyPB) residing on the cell surface (3). CyPB is a member of the cyclophilin (CyP) family and functions as peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase, e.g., during nascent protein folding (18, 27). The requirement for cell surface-resident CyPB could be bypassed by mutating the putative CyPB binding site located near the L2 amino terminus. However, despite bypassing the requirement for cell surface-resident CyPB, HPV16 infectious entry remained sensitive to CyP inhibitors such as cyclosporine (CsA), indicating that CyPs are required at an additional step. Here, we provide cell-biological and -biochemical evidence that CyPs mediate the dissociation of L1 from the L2/viral genome complex during virus uncoating following acidification of endosomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

293TT cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), nonessential amino acids, and antibiotics. HaCaT cells were grown in low-glucose DMEM containing 5% FBS and antibiotics.

Antibodies.

HPV16 L1-specific mouse monoclonal antibody (MAb) H16.56E, 33L1-7, and 312F and HPV16 L2-specific mouse antibody 33L2-1 have been described previously (54, 59, 66). H16.E70, H16.U4, and H16.V5 were a kind gift from N. D. Christensen, Hershey Medical Center. PML protein- and CyPB-specific rabbit antibodies were obtained from Chemicon (ab1370) and Affinity BioReagents, Inc. (PA1-027), respectively. A Click-iT EdU (5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine) imaging kit, Alexa Fluor (AF)-labeled secondary antibodies, and phalloidin were purchased from Invitrogen. Peroxidase-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-mouse antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch.

Plasmids and pseudovirions (PsV).

Codon-optimized HPV16 L1 and L2 expression plasmids were a kind gift from Martin Müller, Heidelberg, Germany (37). Pseudoviruses harboring pEGFP (where EGFP is enhanced green fluorescent protein) were generated using the 293TT cell line as described previously (5). Pseudogenomes were labeled with EdU by supplementing the growth medium with 100 μM EdU at 6 h posttransfection as described previously (30). Particles were characterized by L1- and L2-specific Western blotting, and pseudovirus yield was determined by green fluorescent protein (GFP)-specific quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR).

Inhibitors and reagents.

Cyclosporine was obtained from Toronto Research Chemicals (C988900). Bafilomycin A1 (BafA1) was purchased from Alexis Biochemicals (ALX 380030).

Infection assay.

293TT cells were seeded into 24-well plates, and drugs diluted in complete DMEM were added 24 h later, together with an amount of pseudovirus yielding infection rates of between 5 and 10%. Infectivity was scored by counting GFP-expressing cells at 72 h postinfection (hpi) using flow cytometry.

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Pseudovirions from two preparations were diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), added to a 96-well plate (Nunc-Immuno Module; Nunc) in replicates, and bound for 1 h at 37°C. Subsequently, wells were washed with PBS–0.2% Tween 20 (PBST) and incubated with PBS or a Click-iT reaction cocktail without Alexa Fluor for 30 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the plate was washed with PBST and blocked with 0.01% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBST for 1 h at 37°C. Primary antibody solutions were added (mouse monoclonal 33L1-7, 312F, H16.56E, H16.E70, H16.U4, and H16.V5) for 1 h at 37°C. Bound primary antibody was detected by the addition of horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibody for 30 min at 37°C. The assays were developed with trimethylbenzidine (Promega) and stopped with 1 N HCl. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a FLUOstar-Omega plate reader (BMG Labtech).

Infection in the presence of drugs and immunofluorescence.

HaCaT cells were grown on coverslips at approximately 50% confluence and infected with HPV16 pseudovirus in the presence of 10 μM cyclosporine (CsA)or 100 nM bafilomycin A1 (BafA1). Approximately 5 × 105 to 10 × 105 viral genome equivalents per coverslip were used. EdU staining was performed according to the manufacturer's directions. In brief, at the indicated times postinfection (see below), cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min at room temperature, washed, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 or 0.1% digitonin in PBS for 10 min, washed, and blocked with 5% goat serum in PBS for 30 min, followed by a 30-min incubation with Click-iT reaction cocktail containing Alexa Fluor 555 for EdU-labeled pseudogenome detection. After extensive washing, cells were incubated for 30 min with primary antibodies at room temperature. After extensive washing, cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor-tagged secondary antibodies for 30 min. Phalloidin staining was not used for these samples because it is incompatible with the Click-iT detection reaction. After extensive washing with PBS, cells were mounted in Gold Antifade containing 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Invitrogen). For the colocalization analysis of PsV interactions with the ECM, particles were bound to ECM-coated coverslips (59) for 1 h at 37°C. After incubation, unbound PsV were removed by several washes with PBS. The ECM-bound pseudoviruses were then fixed and stained as described above using a Click-iT EdU imaging kit and 33L1-7 or 33L2-1 antibody. All immunofluorescence (IF) images were captured by confocal microscopy with a 63× objective (Leica TCS SP5 Spectral Confocal Microscope) and processed with Adobe Photoshop software.

The colocalization rate of 33L1-7 and DNA (33L1-1/DNA) or 33L2-1/DNA was determined using LAS AF Lite software. For quantification of ECM-bound PsV, regions of interest (ROIs) from four images were analyzed for each antibody (17 by 100.9 μm2 for 33L1-7 and 17 by 101.3 μm2 for 33L2-1) (Table 1). For quantification of the colocalization rate in HaCaT cells infected with wild-type (wt) HPV16 PsV in the presence or absence of BafA1, groups of 15 cells from three slides were analyzed for each condition. ROIs of cytoplasmic signals only were analyzed. Results are presented as average colocalization rates ± standard deviations (SD).

Table 1.

Results of colocalization analysis obtained using LAS AF software

| Antibody/DNA complex and sample type (n)a | Colocalization rate (avg ± SD [%]) | Pearson's correlation (avg ± SD) | Overlap coefficient (avg ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 33L1-7/DNA | |||

| ECM (17) | 87.9 ± 3.44 | 0.57 ± 0.08 | 0.84 ± 0.03 |

| Cells (15) | |||

| Control | 45.2 ± 6.6 | 0.24 ± 0.06 | 0.34 ± 0.05 |

| BafA1-treated | 91.6 ± 2.9 | 0.75 ± 0.06 | 0.79 ± 0.05 |

| P value | 2.72 × 10−19 | 7.15 × 10−19 | 5.79 × 10−19 |

| 33L2-1/DNA | |||

| ECM (17) | 75.1 ± 4.1 | 0.38 ± 0.02 | 0.54 ± 0.04) |

| Cells (15) | |||

| Control | 73.6 ± 5.7 | 0.39 ± 0.05 | 0.59 ± 0.04 |

| BafA1-treated | 92.6 ± 4.7 | 0.74 ± 0.08 | 0.80 ± 0.06 |

| P value | 6.17 × 10−11 | 2.04 × 10−14 | 5.6 × 10−12 |

n, number of samples.

Alternatively, colocalization of individual EdU-positive dots with capsid proteins was quantified manually. The intensity of each channel signal was measured using LAS AF Lite software for all individual cytoplasmic EdU-positive dots. The same thresholds were set, and 15 to 19 cells for each group from four images were analyzed (Table 2). Results are expressed as an average percentage of EdU-positive dots colocalizing with capsid protein as a function of the total number of EdU-positive dots ± SD.

Table 2.

Results of colocalization study of individual cytoplasmic EdU puncta with capsid proteins

| Antibody and DNA localization | Median no. of EdU puncta per cell (range) by treatment and virus |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (no drug) |

CsA treatment |

CyPB (16L2-GP-N) |

||||

| wt | 16L2-GP-N | wt | 16L2-GP-N | CyPB+ | CyPB− | |

| 33L1-7/DNA (n = 15)a | ||||||

| DNA only | 12 (4–25) | 14 (4–23) | 2 (0–9) | 4 (1–8) | 18 (7–29) | 7 (2–16) |

| L1/DNA | 16 (9–37) | 19 (10–29) | 28 (17–49) | 27 (16–61) | 27 (14–68) | 31 (9–64) |

| DNA total | 32 (15–62) | 33 (14–50) | 32 (17–50) | 32 (17–68) | 40 (31–86) | 41 (13–75) |

| 33L2-1/DNA (n = 19) | ||||||

| DNA only | 6 (0–15) | 5 (2–8) | 5 (2–12) | 5 (1–12) | ||

| L2/DNA | 24 (13–38) | 25 (9–38) | 24 (13–47) | 26 (9–39) | ||

| DNA total | 30 (17–47) | 31 (12–46) | 30 (16–56) | 30 (10–51) | ||

For the CyPB knockdown experiment, n = 17.

Infection and immunofluorescence assay after siRNA knockdown of CyP.

RNA interference was carried out using synthetic small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes with symmetric 3′-deoxythymidine overhangs as previously described (3). Briefly, HaCaT cells were transfected with 3 μg of CyP (broad) (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc.) siRNA duplexes in serum-free medium using MATra reagent (catalog number 7-2001-100; IBA Bio TAGnology, Goettingen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. At 48 h posttransfection, HaCaT cells were harvested with trypsin and reseeded onto coverslips. When cells had attached, they were infected with EdU-labeled 16L2-GP-N mutant pseudovirus. At 18 hpi samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained as described above for EdU and L1 using primary 33L1-7 antibody and anti-mouse AF-tagged secondary antibody. Next, samples were fixed with 70% ethanol (EtOH) containing 50 mM glycine, pH 2.0, for 20 min, washed with PBS, and incubated with CyPB rabbit polyclonal antibody for 30 min. After extensive washing with PBS, cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor-tagged secondary anti-rabbit antibodies for 30 min. Knockdown of CyPs was readily visible in IF staining by lack of reactivity with CyPB antibody.

Expression and purification of GST fusion proteins.

L1/L2 complexes were purified as previously described using the plasmid pET17b-HPV11 L1 cotransformed with a pXA/BN-HPV11 L2 (residues 1 to 455) plasmid into the BL21(DE3) bacterial host (17). Briefly, overnight cultures were used to inoculate 1-liter cultures that were grown to an optical density at 600 nm of ∼0.2 at 37°C. The cultures were then induced with 0.2 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and grown overnight (∼16 h) at 25°C. Cells were pelleted, resuspended in buffer L (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 0.2 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]), lysed using a French press operating at 1,000 lb/in2, and centrifuged to remove cell debris. The resulting lysate was chromatographed using a glutathione-Sepharose (4B GE Healthcare) column. CyPA and CyPB were amplified from HeLa cell cDNA and cloned into pGEX4T-1 using oligonucleotides GGTGAATTCATGGTCAACCCCACCGTG (PPIA-F) and ATTCCCGGGTTATTCGAGTTGTCCACA (PPIA-R) for CyPA and ATTAGAATTCCCTGCTGCCGGGACCTTCTGC (PPIB-F) and CCCGGGATCCACTCCTTGCGCATGGCAA (PPIB-R) for CyPB (restriction enzyme sites used for cloning are highlighted in bold). The pGEX-CyPA and pGEX-CyPB vectors were transformed into BL21 (Stratagene) Escherichia coli for fusion protein expression. The glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusions of CyPA and CyPB proteins were purified as described for the L1/L2 complexes. CyPA and CyPB were enzymatically cleaved from the GST moiety by overnight incubation with thrombin (10 units at 4°C). Before use, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) was added to a final concentration of 5 mM to inactivate residual thrombin.

L1 release assay.

Immobilized HPV 11 L1/L2 complexes (50 μl of glutathione-Sepharose beads) were resuspended in buffer R (50 mM sodium acetate, 0.2 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 5 mM DTT) having a pH of 5.5, 6.0, or 7.4 or in buffer L (pH 8.0) and washed three times to remove unbound protein. All subsequent steps were performed in the buffer of the indicated pH. After the final wash, bead complexes were resuspended in 50 μl of the same buffer. Purified CyPA or CyPB (20 μg) or a buffer control was then added to the GST-L2/L1 bead complexes, and the volume was adjusted to 100 μl. The samples were incubated with inversion at room temperature for 1 h. Beads were collected by centrifugation, and supernatants were saved. The beads were washed three times with buffer. Aliquots of the supernatants and beads were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with L1 antibodies (HPV11 R8363 anti-rabbit polyclonal recombinant L1).

Disassembly of pseudovirions and sucrose gradient sedimentation.

HPV16 pseudovirions were purified by OptiPrep gradient centrifugation as described previously (5). Peak fractions were combined, diluted 1:6 in H2O, and adjusted to 10 mM MgCl2 and 20 mM DTT. After addition of 6 units of DNase I, pseudovirions were incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Solution was adjusted to pH 6.0 by adding 1/10 volume of 0.5 M phosphate buffer, pH 6.0. Subsequently, 25 μg of purified GST-CyPA or GST was added and incubated for an additional 60 min at 37°C. Samples were put on ice; EDTA was added to a final concentration of 20 mM, and samples were loaded onto a 20 to 60% linear sucrose gradient in PBS supplemented with 10 μg of bovine serum albumin and 1 mM DTT. After centrifugation for 3.5 h at 40,000 rpm (SW40 rotor at 4°C), 750-μl fractions were collected from the top. Ten-microliter aliquots were removed for PCR amplification of the pseudogenome. The remainder was precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid as described previously (20). The resulting pellets were analyzed by Western blotting for L1 and L2 using mouse MAbs 16L2-312F and 33L2-1 as primary antibodies.

RESULTS

Binding, internalization, and uncoating of HPV16 L2-GP-N pseudovirus.

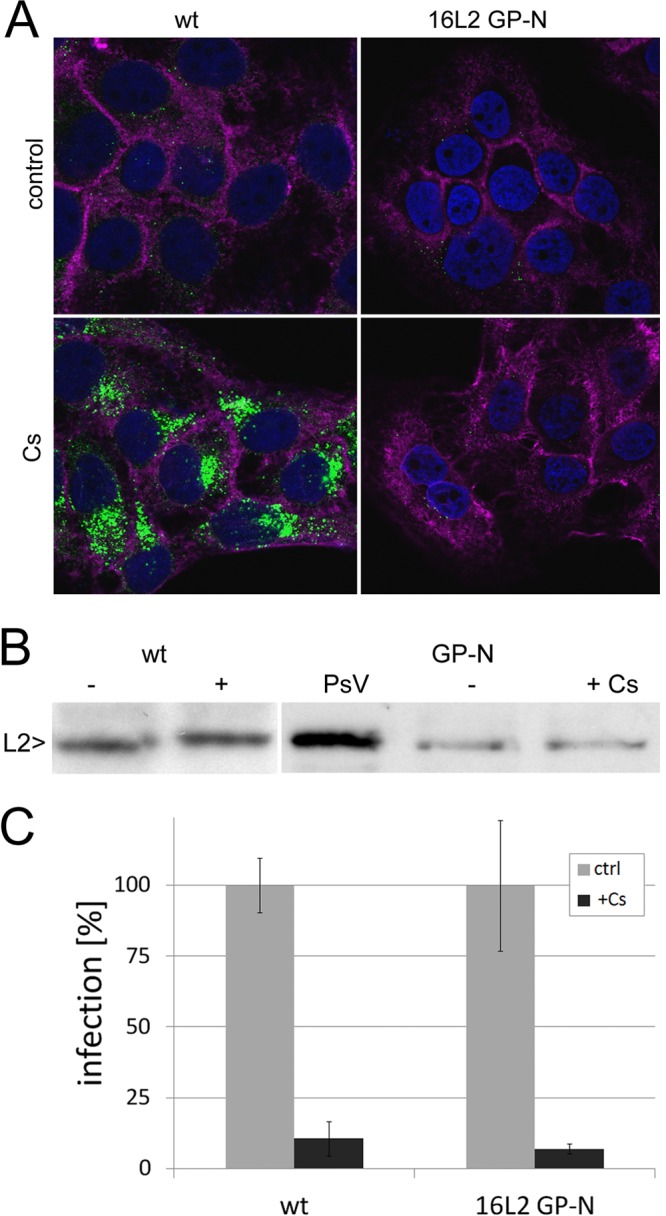

We recently showed that a mutant HPV16 pseudovirus with G99A and P100A amino acid changes in L2 (16L2-GP-N) bypasses the requirement for cell surface CyPB during infectious entry (3). We had found that the mutant 16L2-GP-N but not wt L2 protein exposes the amino terminus after CyP inhibition. This conclusion was further supported by the observation that internalized wt but not mutant HPV16 pseudovirus retained reactivity with the conformation-dependent mouse monoclonal antibody (MAb) H16.56E at 18 h postinfection (hpi) in the presence of the CyP inhibitor cyclosporine (CsA) and after CyPB knockdown (3). At this time point postinfection of the control cells, wt pseudovirus is no longer recognized by H16.56E (Fig. 1A) (59). To further corroborate this finding, we tested for proteolytic cleavage of the 12 amino-terminal residues of L2 protein following infection with wt and mutant pseudovirus. We found that, in contrast to the wt, 16L2-GP-N is cleaved in the presence of CsA, likely by furin convertase (15, 49), resulting in a protein with slightly higher mobility in SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1B). Even though 16L2-GP-N mutant pseudovirus was obviously processed normally on the cell surface in the presence of CyP inhibitors, it remained sensitive to CsA (Fig. 1C) and to CyP knockdown (3). These data suggested that CyP function is required for subsequent steps of infectious entry.

Fig 1.

Characterization of the HPV16 L2-GP-N mutant pseudovirus. (A) HaCaT cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for L1 (green) using MAb H16.56E at 18 hpi with wt and 16L2-GP-N mutant pseudovirus. Nuclei (blue) and filamentous actin (magenta) were stained in addition using DAPI and fluorescently labeled phalloidin, respectively. (B) L2-specific Western blotting of HaCaT cell lysate at 18 hpi with the wt and 16L2-GP-N mutant in the presence or absence of CsA. L2 protein was detected using a mix of RG-1 (22), anti-hemagglutinin, and 33L2-1 MAbs. (C) Sensitivity of wt and 16L2-GP-N mutant pseudovirus infection to 10 μM CsA.

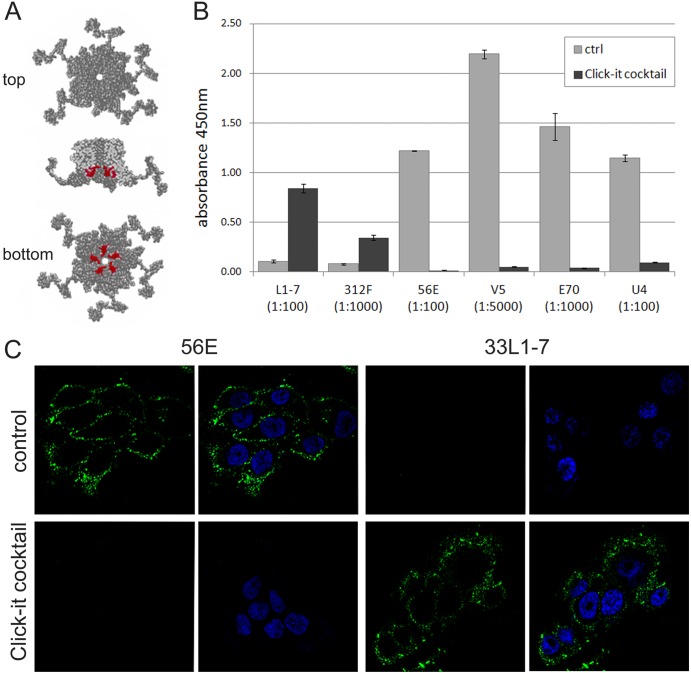

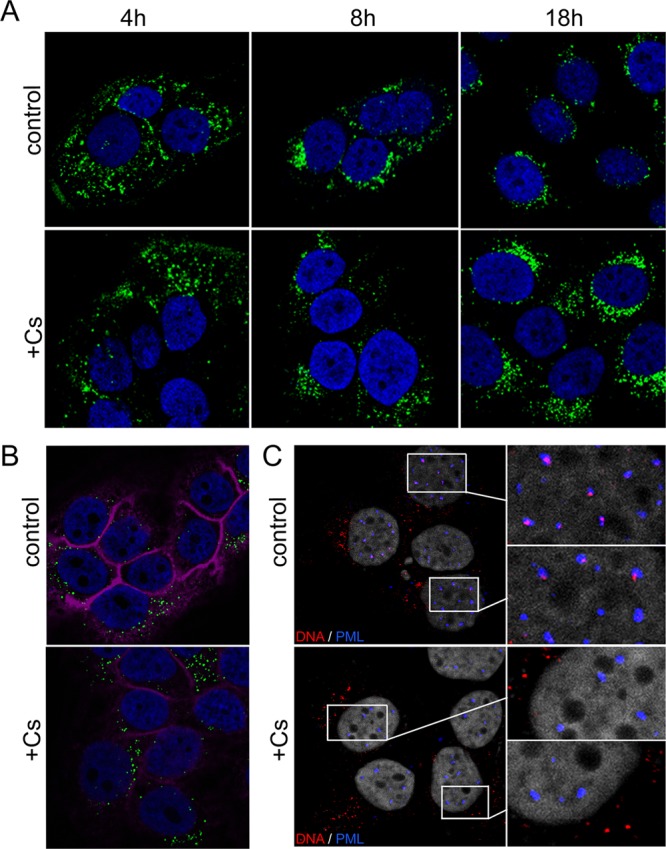

In order to exclude the possibility that virus is lost from the cell surface or not internalized in the presence of CyP inhibitors, we infected HaCaT cells with mutant pseudoviruses and fixed cells at 4, 8, and 18 hpi with paraformaldehyde (PFA). To detect the L1 protein, we denatured the viral capsid proteins by treatment with a Click-iT reaction cocktail prior to staining with MAb 33L1-7. This mouse monoclonal antibody recognizes a conserved linear epitope of the L1 protein (HPV16 L1 residues 303 to 313) that is inaccessible in intact virions, virus-like particles, or capsomeres (51, 54) (Fig. 2A). Under these conditions reactivity is lost with conformation-dependent, neutralizing MAbs but gained with linear epitope-specific MAbs in both ELISA (Fig. 2B) and IF assays (Fig. 2C). We used denaturation of capsid proteins coupled with the use of the linear epitope-specific antibody rather than direct labeling of particles with fluorescent dyes to avoid interference of dyes with binding and internalization events. We also wanted to exclude the possibility of labeling the L2 protein in addition to L1 (see below). As shown in Fig. 3A, CsA treatment did not significantly affect binding of the 16L2-GP-N mutant pseudovirus to the ECM and cell surface. Furthermore, internalization of viral particles was observed at similar levels, suggesting that neither differences in binding nor uptake could explain the 90% reduced infection in the presence of CsA. However, the L1-specific signal strength was reduced in control mutant pseudovirus infection at 18 hpi compared to infection in the presence of CsA, suggesting that degradation of L1 may be impaired in CsA-treated cells. Nonetheless, these data indicate that CsA blocks neither binding nor internalization of mutant virus and, taken together with results presented in Fig. 1, suggested that CyPs are required at a second, possibly intracellular, step during infectious entry of HPV16 pseudovirions.

Fig 2.

Treatment of HPV16 particles with the Click-iT reaction cocktail denatures capsid protein L1. (A) RasMol-generated model of HPV16 L1 capsomeres (Protein Data Bank code 1dzl) highlighting in red the 33L1-7 antibody's conserved linear epitope (residues 303 to 313). (B) HPV16 pseudovirions were bound to ELISA plates and left untreated or treated with the Click-iT reaction cocktail prior to detection with indicated MAbs. Note the gain of reactivity with linear epitope-specific 33L1-7 and 16L1-312F and loss of reactivity with the conformation-dependent MAbs H16.V5, H16.E70, H16.56E, and H16.U4. (C) HaCaT cells were fixed and permeabilized at 4 hpi with wt HPV16 pseudovirions. Samples were either directly stained for conformational or linear L1 epitopes using H16.56E or 33L1-7, respectively, or treated with the Click-iT reaction cocktail prior to incubation with L1-specific antibodies. Again, note the loss of reactivity with H16.56E and gain of reactivity with 33L1-7 after treatment with the Click-iT reaction cocktail. Nuclei are stained with DAPI.

Fig 3.

Binding, internalization, and nuclear transport of the 16L2-GP-N mutant pseudovirus. (A) HaCaT cells were fixed, permeabilized, and treated with a Click-iT reaction cocktail at the indicated times postinfection with mutant pseudovirus in the absence (control) or presence (+) of CsA prior to immunofluorescent staining using MAb 33L1-7. (B) HaCaT cells infected with mutant pseudovirus for 18 h in the absence or presence of CsA were stained for L1 using MAb 33L1-7 without prior denaturation as a measure for uncoating. (C) Delivery of viral pseudogenomes (red) was detected at 24 hpi of HaCaT cells infected with the EdU-labeled mutant pseudovirus. PML protein was stained in blue. Nuclei and filamentous actin were stained with DAPI (blue in panels A and B; gray in panel C) and phalloidin (magenta in panel B). Note the absence of the PML-NB-associated pseudogenome when infection was performed in the presence of CsA.

To resolve the step at which infectious entry of mutant pseudovirus was blocked, we next investigated the effect of CsA treatment on uncoating and nuclear delivery of viral pseudogenomes. To test for uncoating, HaCaT cells were fixed at 18 hpi with the 16L2-GP-N mutant pseudovirus and subsequently permeabilized and stained for L1 using 33L1-7 without prior denaturation. Under these conditions, only those L1 molecules were detected that had the 33L1-7 epitope exposed due to uncoating. Reactivity with MAb 33L1-7 following infectious entry is well established as a measure of uncoating (3, 34, 63). We observed equally strong 33L1-7-specific signals in control and CsA-treated cells, indicating that uncoating of mutant pseudovirus was not impaired by CsA (Fig. 3B). In contrast to this observation, we had previously shown that uncoating of the wt HPV16 pseudovirus was blocked either in the presence of CsA or after knockdown of CyPB (3). These data confirm that CsA blocks wt and mutant pseudovirus at different stages during viral entry.

We next tested for delivery of viral pseudogenomes to the subnuclear PML-NB. In order to follow viral DNA, the pseudogenomes were labeled in vivo using the nucleotide derivative 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) so that EdU-labeled viral pseudogenomes could be visualized using the Click-iT reaction cocktail (30). We also costained for PML protein to verify delivery of pseudogenomes to PML-NB (14). As shown in Fig. 3C, viral genomes were detected at PML-NB in untreated control cells. However, EdU staining was always restricted to the cytoplasm of CsA-treated cells, indicating that their nuclear delivery was blocked by CsA. Taken together, these data suggest that entry of the mutant 16L2-GP-N pseudovirus is blocked by CyP inhibitors between uncoating of the viral capsid and nuclear accumulation of the viral genome.

Dissociation of L1 and L2 in vitro.

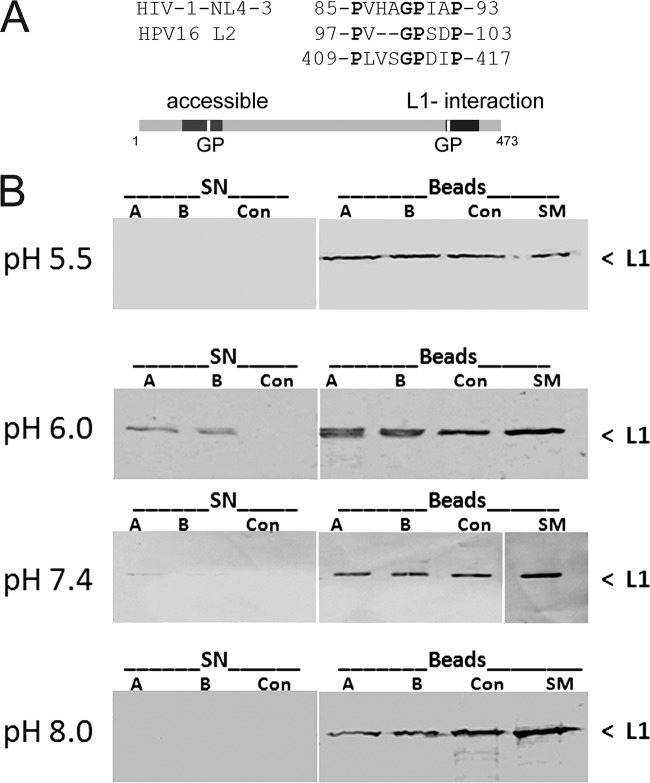

A putative CyP binding site can be identified adjacent to the peptide domain of L2 that mediates interaction with L1 capsomeres (Fig. 4A) (3, 17, 42), suggesting that CyPs mediate dissociation of the L1 and L2 capsid proteins. To test this hypothesis, we first investigated the dissociation of L1 and L2 in an in vitro assay format, which had previously been developed to identify HPV11 L2 amino acid residues interacting with HPV11 capsomeres. HPV11 L1 was coexpressed with GST-L2 in E. coli. The intracellular complexes between L1 capsomeres and the GST-L2 fusion protein were extracted and bound to glutathione-agarose beads as previously described (17). The beads were sequentially incubated with purified CyPA or CyPB at different pHs. We varied the pH in this release assay because acidification of endosomes is an essential step for infectious entry of HPV (16, 61). Dissociation of L1 and L2 was measured by the appearance of L1 protein in supernatants using L1-specific Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 4B, all beads loaded with the GST-L2 fusion protein had L1 protein bound in similar amounts. Incubation with both CyPA and CyPB but not with a buffer control induced the release of L1 from beads in a pH-dependent manner. L1 dissociation from L2 was most efficient at pH 6.0, less efficient at pH 7.4, and undetectable at pH 5.5 and 8.0. Since CyPA and CyPB differ in their intracellular localizations but not in their enzymatic activities, it was expected that they might behave similarly in vitro. These data support the hypothesis that CyPs can catalyze the dissociation of L1/L2 complexes and led us to further investigate the dissociation of capsid proteins during virus entry. Since acidification of endosomes increases during maturation, ranging from pH 6.1 to 6.8 in early endosomes to 6.0 to 4.8 in late endosomes, these results were a first indication that dissociation may occur in the early endosomal compartment (28, 44).

Fig 4.

In vitro dissociation of HPV11 L1 from complexes of L1 and GST-L2 by CyPs. (A) Sequence comparison of putative CyP binding sites. (B) Complexes of L1 and GST-L2 bound to glutathione Sepharose beads were incubated with CyPA, CyPB, or buffer control at the indicated pH. L1 released from the complex into the supernatant was assayed by Western blotting with anti-L1 antibody. SN supernatant; A, CyPA; B, CyPB; Con, buffer-alone control; SM, starting material bound to the beads.

HPV16 capsid protein dissociation during pseudovirus internalization.

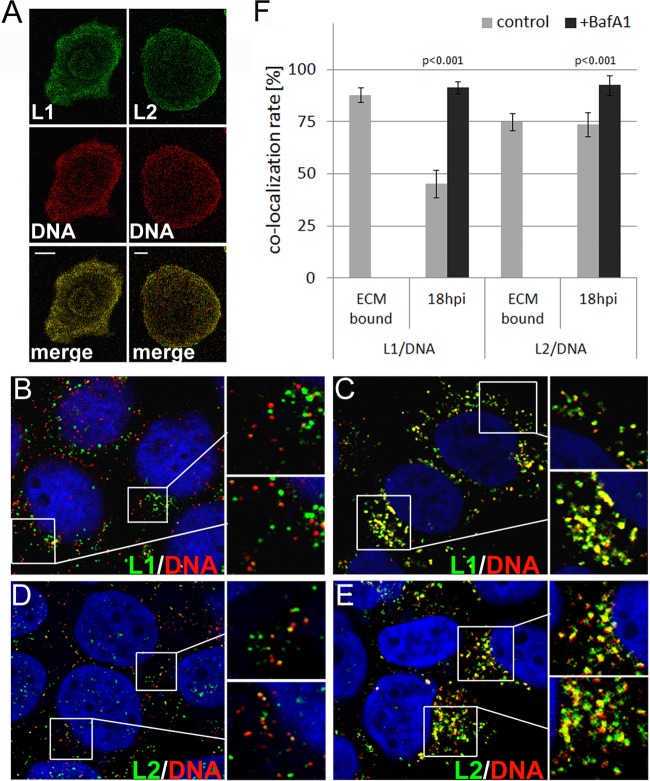

We next investigated the dissociation of capsid proteins following infection of HaCaT cells with wt and mutant pseudoviruses using IF. We quantified the extent of colocalization between pseudogenomes and capsid proteins using the colocalization module of the LAS AF software provided by Leica to enable a quantitative analysis and to address the inherent deficiencies of the IF analysis, such as nonspecific staining, differences in sensitivities, and presence of L1-only viral particles. EdU-labeled viral particles were bound to ECM-coated coverslips. Following fixation, capsid proteins were denatured by treatment with a Click-iT reaction cocktail and stained for L1 or L2 using 33L1-7 or 33L2-1, respectively (Fig. 5A). 33L2-1 binds to a linear epitope of the HPV16 and HPV33 L2 proteins spanning amino acid residues 163 to 170 and, similar to 33L1-7, recognizes only denatured L2 protein (66). The extent of colocalization reached 88% ± 3.4% and 75% ± 4.1% for L1/DNA and L2/DNA, respectively (Fig. 5F; Table 1). That the level of L2/DNA colocalization was lower than that of L1/DNA probably reflects the lower copy number of L2 in the viral capsid and the fact that L1 can form pseudoviral particles in the absence of L2.

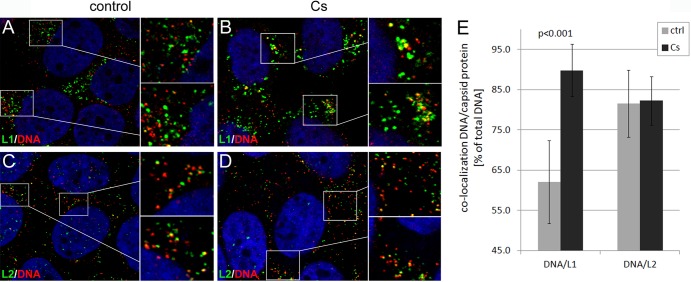

Fig 5.

Colocalization of pseudogenome with capsid proteins. (A) EdU-labeled wt pseudoparticles were bound to ECM-coated coverslips and stained for DNA (red) and capsid proteins (green) using 33L1-7 and 33L2-1 for L1 and L2, respectively. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B to E) HaCaT cells were infected with EdU-labeled wt pseudovirus in the absence (B and D) or presence of bafilomycin A1 (C and E). Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained as above for the pseudogenome (B to E) and L1 (B and C) or for the pseudogenome and L2 (D and E) at 18 hpi. Nuclei were stained using DAPI (in blue). Areas highlighted by rectangles are magnified in the smaller panels shown to the right. Merged images are shown. (F) Extent of L1/DNA and L2/DNA colocalization as determined by using LAS AF software.

To calibrate this assay and determine the maximal and minimal levels of colocalization achievable under the assay conditions, we measured the extent of colocalization of L1/DNA and L2/DNA in HaCaT cells at 18 hpi with wt pseudovirus in the absence or the presence of bafilomycin A1 (BafA1) (Fig. 5B to E). BafA1 blocks acidification of endosomes and is a well-established inhibitor of HPV16 infection that blocks uncoating (6). We reasoned that BafA1 treatment would block the dissociation of L1 from the pseudogenome and thus significantly change the extent of L1/DNA colocalization. Dissociation of L1 from the pseudogenome was readily detected by IF at 18 hpi of HaCaT cells with wt HPV16 pseudovirus, as evidenced by vesicles staining for either EdU or L1 alone (Fig. 5B). The extent of L1/DNA colocalization was increased from 45.2% ± 6.6% in a control infection to 91.6% ± 2.9% in cells treated with BafA1 (Fig. 5C and F; Table 1). In contrast, the L2/DNA colocalization in a control infection was similar to that of ECM-bound particles; however, it increased in cells treated with BafA1 (73.6% ± 5.7% versus 92.6% ± 4.7%) (Fig. 5D to F; Table 1). The increased extent of L2/DNA colocalization in BafA1-treated cells compared to ECM-resident particles may be due to endocytic vesicles that contain more than one viral particle, thus increasing the likelihood of detecting L2 capsid protein. Similar to CsA treatment, BafA1 treatment increases signal strength for L1, L2, and DNA, again indicating that this drug might interfere with the degradation of viral components. To restrict our quantitative analysis to pseudogenome-containing particles and exclude the analysis of DNA-free particles present in our pseudovirus preparations, we repeated the measurements by manually analyzing all individual EdU-positive cytoplasmic puncta for the presence of capsid proteins. For this, the intensity of each channel signal was measured for all individual cytoplasmic EdU-positive dots. In control infections, 62.1% ± 10.8% and 81.5% ± 8.3% of all EdU-positive puncta were also positive for L1 and L2 protein, respectively. From these observations we conclude that dissociation of L1 protein from the viral pseudogenome can be detected with this methodology. A probable reason for the low dissociation efficiency is the well-established slow internalization of HPV (half-times of up to 14 h have been reported) (10, 24, 60, 62).

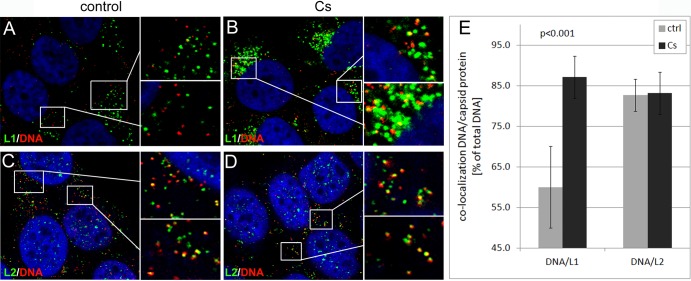

CyP inhibition and knockdown block dissociation of L1 from the L2/genome complex in vivo.

Using manual measurements, we studied the effect of CsA on the dissociation of the L1 protein from viral pseudogenomes. In contrast to results with control infections, we found that the majority of vesicles staining for DNA were also positive for the L1 protein at 18 hpi with mutant pseudovirus (Fig. 6A and B). However, many L1-positive vesicles appeared increased in size compared to those of the control infection, again indicating that CsA might have off-target effects. CsA treatment increased levels of L1/DNA colocalization from 60% ± 10.1% to 87.1% ± 5.2% (Fig. 6E; Table 2). In contrast, the rate of L2/DNA colocalization was not significantly altered by CsA treatment (Fig. 6C to E; Table 2). As a control, we infected HaCaT cells with the wt HPV16 pseudovirus in the presence of CsA. Similar to BafA1, CsA blocks uncoating of wt HPV16 pseudovirions due to the inhibition of L2 conformational changes occurring on the cell surface (3). Again, the level of L1/DNA colocalization was increased from 62.1% ± 10.3% to 89.8% ± 6.5% (Fig. 7 and Table 2). As expected, the L2/DNA colocalization was not changed by CsA treatment. This result is consistent with the hypothesis that the L1 but not the L2 protein dissociates from the viral genome and that its dissociation requires CyP activity.

Fig 6.

CsA interferes with dissociation of L1 from the L2/DNA complex during infectious entry of 16L2-GP-N mutant pseudovirus. (A to D) HaCaT cells were fixed, permeabilized, and sequentially stained for DNA (red) and L1 (green) (A and B) or DNA and L2 (green) (C and D) using a Click-iT reaction cocktail and MAbs 33L1-7 or 33L2-1 at 18 hpi with EdU-labeled 16L2-GP-N mutant pseudovirus in the absence (A and C) or presence (B and D) of CsA. Areas highlighted by rectangles are magnified in the smaller panels shown to the right. (E) L1/DNA and L2/DNA colocalizations were manually quantified as outlined in Materials and Methods. P values were determined by a Student's t test.

Fig 7.

CsA interferes with dissociation of L1 from the L2/DNA complex during infectious entry of wt pseudovirus. (A to D) HaCaT cells were fixed, permeabilized, and sequentially stained for DNA (red) and L1 (green) (A and B) or L2 (green) (C and D) using a Click-iT reaction cocktail and MAb 33L1-7 or 33L2-1 at 18 hpi with EdU-labeled wt pseudovirus in the absence (A and C) or presence (B and D) of CsA. Areas highlighted by rectangles are magnified in the smaller panels shown to the right. (E) L1/DNA and L2/DNA colocalizations were manually quantified as outlined in Materials and Methods. P values were determined by a Student's t test.

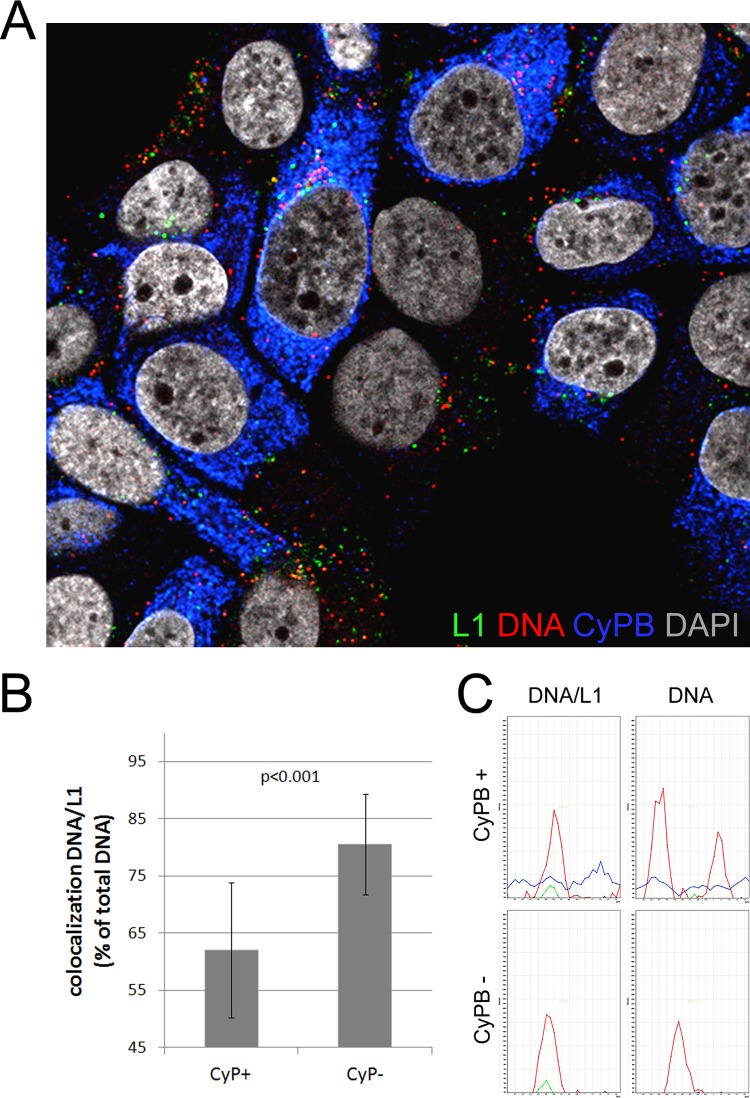

To confirm these findings and control for possible off-target effects of CsA, we knocked down CyPA and CyPB using an siRNA that targets both CyPs and efficiently inhibits wt as well as mutant HPV16 pseudoinfection (3). At 48 h posttransfection of the siRNA, HaCaT cells were infected with EdU-labeled 16L2-GP-N mutant pseudovirus. The immunofluorescent staining was modified to detect CyPB (see Materials and Methods). Cells knocked down for CyPB were readily identified (Fig. 8A). Compared to L1 levels after CsA treatment, the L1 protein levels in CyPB-deficient cells were reduced significantly, indicating that the previously observed increase in L1 levels (Fig. 3A) was likely due to off-target effects of CsA. Quantification of individual EdU-positive puncta revealed that the knockdown increased the extent of L1/DNA colocalization from 62.0% ± 11.8% to 80.5% ± 8.8% (Fig. 8B and C; Table 2), confirming the requirement of CyPs for efficient dissociation of L1 from the L2/DNA complex. Increased signal intensity of CyPB in EdU-positive puncta additionally indicates the presence of CyPB in viral genome-containing vesicles. Where CyPB is derived from is unclear at the moment. However, it could be cointernalized with viral particles or, alternatively, be present in intracellular vesicles fusing with the virus containing early endosomes.

Fig 8.

Cyclophilin knockdown interferes with dissociation of L1 from the pseudogenome. (A) HaCaT cells were transfected with CyP (broad) siRNA. At 48 h posttransfection, cells were infected with EdU-labeled 16L2-GP-N mutant pseudovirus for 18 h. Cells were sequentially stained for EdU-labeled DNA (red), L1 (green), and CyPB (blue) as described in Materials and Methods. DAPI-stained nuclei are depicted in gray. (B) L1/DNA colocalization was quantified in CyPB-positive and -negative cells. (C) Representative graphs of signal intensity in a single punctum in CyPB-positive and -negative cells. Note the increased CyPB signal in EdU-positive puncta. P values were determined by a Student's t test.

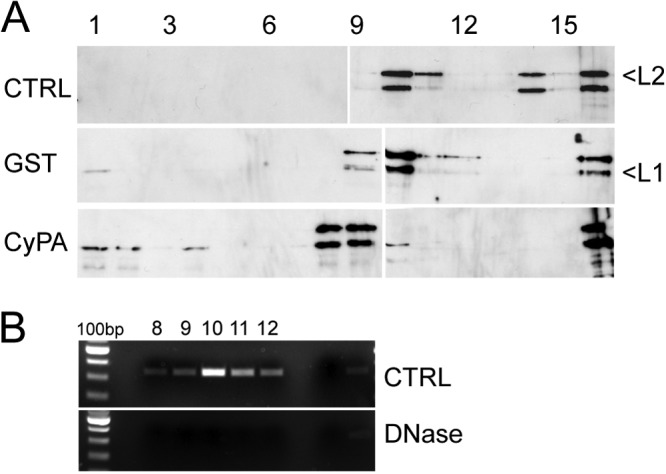

CyP facilitates partial release of L1 from HPV16 pseudovirus in vitro.

Finally, we investigated the effect of CyP on the L1-L2 interaction in HPV16 pseudoviral particles. Since no host cell factors required for uncoating have been identified as yet and since it is unknown how the critical disulfide bonds are reduced during viral entry, we treated purified pseudovirions with DTT to reduce intercapsomeric disulfide bonds prior to incubation with purified CyPA. We also incubated the reduced capsid with DNase I to restrict our analysis to protein-protein interactions and avoid possible interference by capsid protein interactions with encapsidated chromatin. These partially disassembled HPV16 pseudovirions were then incubated with a purified GST-CyPA fusion protein or GST at pH 6.0. Products were separated by sucrose gradient sedimentation, and fractions were analyzed by L1- and L2-specific Western blotting. Under these conditions, untreated pseudovirions were mainly detected in fraction 11 of the gradient as evidenced by the presence of L1, L2, and DNA (Fig. 9). Probably as the result of the slightly acidic pH, some aggregated pseudovirus was also found near the bottom of the tube. Treatment with DTT, DNase I, and GST only slightly changed the sedimentation of pseudovirions. DNA was no longer detectable by PCR, indicating that the DNase treatment was effective. However, incubation with a GST-CyPA fusion protein resulted in a partial release of L1 from HPV16 particles; L1 was found at the top of the gradient, where capsomeres are expected to migrate under these conditions (55). All of the L2 and some L1 protein were still present in large aggregates migrating into the 60% sucrose cushion. A weak L1 signal was also found at the top of gradient in the GST control. This is probably due to L1-only particles, which are always present at low levels in our pseudovirus preparations. This sedimentation profile suggests that CyPA can facilitate the dissociation of L1 protein from partially disassembled pseudovirions in vitro at slightly acidic pH.

Fig 9.

Partial dissociation of HPV16 L1 capsomeres from pseudovirions in vitro by CyPA. (A) HPV16 pseudovirus was treated with DNase I and DTT or left untreated. After adjustment to pH 6.0, samples were incubated with GST or CyPA and analyzed by sedimentation through sucrose gradients. Gradients were fractionated from the top, and fractions were assayed for the presence of L1 and L2 by Western blotting following concentration of proteins by trichloroacetic acid precipitation. (B) GFP-specific DNA fragments were amplified by PCR from the indicated fractions and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that the major capsid protein L1 of HPV16 dissociates from the viral pseudogenome and L2 protein following uncoating in acidified endosomes. Combining capsid protein denaturation with linear epitope-specific antibodies for detection of capsid proteins and EdU-labeled pseudogenomes, we were able to follow the three components of the HPV16 particles during infectious entry. Our quantitative analyses for measuring the level of colocalization yielded significant results despite the complexities and deficiencies of the assay system, including the asynchronous internalization of HPV16 pseudovirions and the different limits of detection for L1 and L2 protein, e.g., due to differences in copy numbers. We partially accounted for the different sensitivities by calibrating our system using ECM-bound viral particles and inhibitors of uncoating, which yielded the maximally achievable level of colocalization. Asynchronous internalization was evidenced by the observation that approximately 60% of all EdU-positive puncta were still positive for L1 at 18 hpi. We did not attempt to synchronize HPV16 entry to increase the impact of CsA treatment and CyP knockdown because this condition requires the use of additional drugs or antibodies that might have interfered with the analysis. The continued colocalization of L2 and viral pseudogenomes during infectious internalization served as an internal control for our treatments and measurements.

We utilized the 16L2-GP-N mutant pseudovirus that has been shown to bypass the requirement for cell surface CyPB (3) in order to investigate the role of CyPs in dissociating the L1 protein from the pseudoviral genome. The CyP inhibitor CsA and knockdown of CyPA and CyPB significantly increased colocalization of L1 and DNA without altering the L2/DNA colocalization, supporting the view that these host cell chaperones facilitate the release of L1 from the L2/DNA complex. Treatment with CsA yielded higher levels of L1/DNA colocalization than siRNA-mediated knockdown. The increased level of colocalization may partially be explained by the off-target effects of CsA that impair the degradation of L1 protein, thus increasing detection of L1 protein by IF, which is not seen after CyP knockdown. This may result in an underestimation of the levels of colocalization after knockdown. Furthermore, CyP family members that are not targeted by the siRNA may substitute for CyPA and CyPB.

The ability of purified CyPs to catalyze the release of L1 from the GST-L2 fusion protein and also from partially disassembled HPV16 pseudovirions in vitro provides additional support for a role of CyPs in the uncoating process of HPV16. We utilized HPV11 capsid proteins expressed in E. coli to investigate the effect of purified CyPA and CyPB on the integrity of L1/L2 complexes. Since HPV6 pseudoinfection is sensitive to CyP inhibitors (3) and since the CyP binding sites are conserved in HPV6, HPV11, and HPV16, the use of an alternative HPV type was thought to be valid, as well as extending the mechanism beyond HPV16. The CyP-mediated dissociation was equally efficient in the presence of either CyPA or CyPB, presumably because in vitro the specificity is lost. We also showed that CyPA induces the release of L1 capsomeres from HPV16 pseudovirions treated with reducing agents and DNase I prior to addition of CyPA. This reaction was less efficient than the release of L1 capsomeres from GST-L2 fusion proteins. Based on reports for other viruses, e.g., simian virus 40 (SV40) (23, 25), we must assume, however, that many factors are involved in uncoating and that our partial in vitro disassembly does not fully mimic the processes occurring in vivo. The dissociation of capsid proteins in vitro required slightly acidic pH, indicating that dissociation may also occur after acidification of endosomes in vivo. However, this possibility cannot be tested directly since the manipulation of endosomal acidification (e.g., by treatment with BafA1, chloroquine, or NH4Cl) itself interferes with the initial uncoating. Uncoating is likely a prerequisite allowing access of CyPs to the otherwise hidden internal carboxy terminus of L2.

The L2 protein of bovine papillomavirus type 1 (BPV-1) was shown to escape endosomes together with the viral genome prior to their accumulation at PML-NB (14, 33). However, the fate of the L1 protein was not studied due to a lack of suitable reagents. Our data indicate that the L1 protein of HPV16 dissociates from the L2/DNA complex prior to its egress from endosomes and is retained in the endocytic compartment, where it appears targeted for degradation. L1 degradation is suggested by the loss of the L1 signal in untreated cells compared to results in CsA- or BafA1-treated cells. The continued colocalization of viral pseudogenomes with the endosomal marker EEA-1 also suggests that dissociation of capsid proteins is associated with sorting into different vesicular compartments prior to endosomal egress rather than occurring during egress of the L2/DNA from endocytic vesicles. The driving force for sorting is unknown at present. However, the L1 and L2 proteins may interact with different uptake receptors, thus determining the subsequent intracellular trafficking of L1- and L2-containing vesicles. Evidence for L1 and L2 interactions with secondary non-HSPG uptake receptors has been reported (31, 69). Sorting nexin 17, a host cell factor involved in vesicular trafficking (11) and an interaction partner of HPV16 L2 (2), may also be involved in the sorting of L2/DNA- and L1 protein-containing vesicles.

In addition to HPV, many viruses, e.g., lentiviruses and hepatitis C virus (HCV), depend on cyclophilin function for completion of their life cycle. The interaction of CyPA and CyPB with nonstructural (NS) HCV proteins NS5A, NS5B, and NS2 is required for efficient RNA replication (21, 65, 67). However, CyPs are also important for establishing infection of other viruses by contributing to efficient entry into host cells. CyPA facilitates the entry of mouse cytomegalovirus into neural progenitor/stem cells by unknown mechanisms (35). Both CyPA and Pin1, the latter specific for proline residues that are preceded by a phosphorylated serine/threonine residue, have been implicated in the uncoating of the HIV capsid following infectious entry (41, 45). In addition, Pin1 has been shown to facilitate HIV capsid disassembly in vitro (45). However, the CyP-mediated dissociation of viral capsid proteins has not been observed as yet. We have not identified the specific CyP family member involved in HPV entry due in part to the lack of suitable reagents for immunofluorescent detection of CyPA. Also, CyPA and CyPB are both found on the cell surface (7, 64). Therefore, they may be coendocytosed with viral particle/receptor complexes and contribute to capsid protein dissociation. This scenario is supported by the finding that knockdown of both CyPs impairs infection to a much greater extent than individual knockdown of either CyPA or CyPB (3).

Nonenveloped viruses must shed their protein shells during infectious entry. Adenoviruses undergo a number of conformational changes that result in shedding of minor capsid components, like fiber, and exposure of membrane-penetrating protein domains, like pVI (26, 46, 68). However, the major capsid proteins reach the cytosol together with the viral genome. Complete disassembly occurs at nuclear pores, where the viral genome is injected into the nucleus and the capsid remains in the cytosol (38). Similarly, the small DNA tumor viruses SV40 and mouse polyomavirus escape the endoplasmic reticulum and reach the cytosol as conformationally modified but largely intact virions (29, 43). Our data suggest that HPV16, to gain access to the nucleus, has developed unique strategies that involve complete shedding of the major capsid protein in the endocytic compartment prior to egress from endosomes in addition to a slow half-time of internalization (60), the use of a novel endocytic pathway (56), the dependence on proteolytic cleavage of capsid proteins (49), and the requirement for nuclear envelope breakdown for establishing infection (48).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Jia Pang for excellent technical assistance, members of the Sapp lab for helpful discussions, and N.D. Christensen, M. Müller, R. B. Roden, and J. T. Schiller for providing reagents.

The project described was supported by R01AI081809 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to M.S. and by R01CA37667 from the National Cancer Institute to R.L.G. This project was also supported in part by grants from the National Center for Research Resources (5P20RR018724-10) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (8 P20 GM103433-10) from the National Institutes of Health.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 July 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Baker TS, et al. 1991. Structures of bovine and human papillomaviruses. Analysis by cryoelectron microscopy and three-dimensional image reconstruction. Biophys. J. 60:1445–1456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bergant Marusic M, Ozbun MA, Campos SK, Myers MP, Banks L. 2012. Human papillomavirus L2 facilitates viral escape from late endosomes via sorting nexin 17. Traffic 13:455–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bienkowska-Haba M, Patel HD, Sapp M. 2009. Target cell cyclophilins facilitate human papillomavirus type 16 infection. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000524 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Buck CB, et al. 2008. Arrangement of L2 within the papillomavirus capsid. J. Virol. 82:5190–5197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buck CB, Pastrana DV, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. 2004. Efficient intracellular assembly of papillomaviral vectors. J. Virol. 78:751–757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Campos SK, Chapman JA, Deymier MJ, Bronnimann MP, Ozbun MA. 2012. Opposing effects of bacitracin on human papillomavirus type 16 infection: enhancement of binding and entry and inhibition of endosomal penetration. J. Virol. 86:4169–4181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carpentier M, et al. 1999. Two distinct regions of cyclophilin B are involved in the recognition of a functional receptor and of glycosaminoglycans on T lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 274:10990–10998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen XS, Garcea RL, Goldberg I, Casini G, Harrison SC. 2000. Structure of small virus-like particles assembled from the L1 protein of human papillomavirus 16. Mol. Cell 5:557–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen XS, Stehle T, Harrison SC. 1998. Interaction of polyomavirus internal protein VP2 with the major capsid protein VP1 and implications for participation of VP2 in viral entry. EMBO J. 17:3233–3240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Christensen ND, Cladel NM, Reed CA. 1995. Postattachment neutralization of papillomaviruses by monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies. Virology 207:136–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cullen PJ, Korswagen HC. 2012. Sorting nexins provide diversity for retromer-dependent trafficking events. Nat. Cell Biol. 14:29–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Culp TD, Budgeon LR, Christensen ND. 2006. Human papillomaviruses bind a basal extracellular matrix component secreted by keratinocytes which is distinct from a membrane-associated receptor. Virology 347:147–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dasgupta J, et al. 2011. Structural basis of oligosaccharide receptor recognition by human papillomavirus. J. Biol. Chem. 286:2617–2624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Day PM, Baker CC, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. 2004. Establishment of papillomavirus infection is enhanced by promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML) expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:14252–14257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Day PM, Gambhira R, Roden RB, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. 2008. Mechanisms of human papillomavirus type 16 neutralization by L2 cross-neutralizing and L1 type-specific antibodies. J. Virol. 82:4638–4646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Day PM, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. 2003. Papillomaviruses infect cells via a clathrin-dependent pathway. Virology 307:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Finnen RL, Erickson KD, Chen XS, Garcea RL. 2003. Interactions between papillomavirus L1 and L2 capsid proteins. J. Virol. 77:4818–4826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fischer G, Wittmann-Liebold B, Lang K, Kiefhaber T, Schmid FX. 1989. Cyclophilin and peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase are probably identical proteins. Nature 337:476–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Florin L, et al. 2006. Identification of a dynein interacting domain in the papillomavirus minor capsid protein L2. J. Virol. 80:6691–6696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Florin L, et al. 2004. Nuclear translocation of papillomavirus minor capsid protein L2 requires Hsc70. J. Virol. 78:5546–5553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Foster TL, Gallay P, Stonehouse NJ, Harris M. 2011. Cyclophilin A interacts with domain II of hepatitis C virus NS5A and stimulates RNA binding in an isomerase-dependent manner. J. Virol. 85:7460–7464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gambhira R, et al. 2007. A Protective and broadly cross-neutralizing epitope of human papillomavirus L2. J. Virol. 81:13927–13931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Geiger R, et al. 2011. BAP31 and BiP are essential for dislocation of SV40 from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol. Nat. Cell Biol. 13:1305–1314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Giroglou T, Florin L, Schäfer F, Streeck RE, Sapp M. 2001. Human papillomavirus infection requires cell surface heparan sulfate. J. Virol. 75:1565–1570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Goodwin EC, et al. 2011. BiP and multiple DNAJ molecular chaperones in the endoplasmic reticulum are required for efficient simian virus 40 infection. mBio. 2:e00101–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Greber UF, Willetts M, Webster P, Helenius A. 1993. Stepwise dismantling of adenovirus 2 during entry into cells. Cell 75:477–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harding MW, Handschumacher RE, Speicher DW. 1986. Isolation and amino acid sequence of cyclophilin. J. Biol. Chem. 261:8547–8555 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huotari J, Helenius A. 2011. Endosome maturation. EMBO J. 30:3481–3500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Inoue T, Tsai B. 2011. A large and intact viral particle penetrates the endoplasmic reticulum membrane to reach the cytosol. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002037 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ishii Y, et al. 2010. Inhibition of nuclear entry of HPV16 pseudovirus-packaged DNA by an anti-HPV16 L2 neutralizing antibody. Virology 406:181–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Johnson KM, et al. 2009. Role of heparan sulfate in attachment to and infection of the murine female genital tract by human papillomavirus. J. Virol. 83:2067–2074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Joyce JG, et al. 1999. The L1 major capsid protein of human papillomavirus type 11 recombinant virus-like particles interacts with heparin and cell-surface glycosaminoglycans on human keratinocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 274:5810–5822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kämper N, et al. 2006. A membrane-destabilizing peptide in capsid protein L2 is required for egress of papillomavirus genomes from endosomes. J. Virol. 80:759–768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Karanam B, et al. 2010. Papillomavirus infection requires gamma secretase. J. Virol. 84:10661–10670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kawasaki H, Mocarski ES, Kosugi I, Tsutsui Y. 2007. Cyclosporine inhibits mouse cytomegalovirus infection via a cyclophilin-dependent pathway specifically in neural stem/progenitor cells. J. Virol. 81:9013–9023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Knappe M, et al. 2007. Surface-exposed amino acid residues of HPV16 L1 protein mediating interaction with cell surface heparan sulfate. J. Biol. Chem. 282:27913–27922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Leder C, Kleinschmidt JA, Wiethe C, Müller M. 2001. Enhancement of capsid gene expression: preparing the human papillomavirus type 16 major structural gene L1 for DNA vaccination purposes. J. Virol. 75:9201–9209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Leopold PL, Crystal RG. 2007. Intracellular trafficking of adenovirus: many means to many ends. Adv. Drug Deliv Rev. 59:810–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li M, Beard P, Estes PA, Lyon MK, Garcea RL. 1998. Intercapsomeric disulfide bonds in papillomavirus assembly and disassembly. J. Virol. 72:2160–2167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liu WJ, et al. 1997. Sequence close to the N terminus of L2 protein is displayed on the surface of bovine papillomavirus type 1 virions. Virology 227:474–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Luban J. 2007. Cyclophilin A, TRIM5, and resistance to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 81:1054–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Luban J, Bossolt KL, Franke EK, Kalpana GV, Goff SP. 1993. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein binds to cyclophilins A and B. Cell 73:1067–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Magnuson B, et al. 2005. ERp29 triggers a conformational change in polyomavirus to stimulate membrane binding. Mol. Cell 20:289–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mercer J, Schelhaas M, Helenius A. 2010. Virus entry by endocytosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79:803–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Misumi S, et al. 2010. Uncoating of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 requires prolyl isomerase Pin1. J. Biol. Chem. 285:25185–25195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nakano MY, Boucke K, Suomalainen M, Stidwill RP, Greber UF. 2000. The first step of adenovirus type 2 disassembly occurs at the cell surface, independently of endocytosis and escape to the cytosol. J. Virol. 74:7085–7095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Okun MM, et al. 2001. L1 interaction domains of papillomavirus L2 necessary for viral genome encapsidation. J. Virol. 75:4332–4342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pyeon D, Pearce SM, Lank SM, Ahlquist P, Lambert PF. 2009. Establishment of human papillomavirus infection requires cell cycle progression. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000318 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Richards RM, Lowy DR, Schiller JT, Day PM. 2006. Cleavage of the papillomavirus minor capsid protein, L2, at a furin consensus site is necessary for infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:1522–1527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Roden RB, et al. 2000. Minor capsid protein of human genital papillomaviruses contains subdominant, cross-neutralizing epitopes. Virology 270:254–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rommel O, et al. 2005. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans interact exclusively with conformationally intact HPV L1 assemblies: basis for a virus-like particle ELISA. J. Med. Virol. 75:114–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sapp M, Bienkowska-Haba M. 2009. Viral entry mechanisms: human papillomavirus and a long journey from extracellular matrix to the nucleus. FEBS J. 276:7206–7216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sapp M, Fligge C, Petzak I, Harris JR, Streeck RE. 1998. Papillomavirus assembly requires trimerization of the major capsid protein by disulfides between two highly conserved cysteines. J. Virol. 72:6186–6189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sapp M, et al. 1994. Analysis of type-restricted and cross-reactive epitopes on virus-like particles of human papillomavirus type 33 and in infected tissues using monoclonal antibodies to the major capsid protein. J. Gen. Virol. 75:3375–3383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sapp M, Volpers C, Müller M, Streeck RE. 1995. Organization of the major and minor capsid proteins in human papillomavirus type 33 virus-like particles. J. Gen. Virol. 76:2407–2412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Schelhaas M. 2010. Come in and take your coat off—how host cells provide endocytosis for virus entry. Cell Microbiol. 12:1378–1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Schelhaas M, et al. 2012. Entry of human papillomavirus type 16 by actin-dependent, clathrin- and lipid raft-independent endocytosis. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002657 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Schneider MA, Spoden GA, Florin L, Lambert C. 2011. Identification of the dynein light chains required for human papillomavirus infection. Cell Microbiol. 13:32–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Selinka HC, et al. 2007. Inhibition of transfer to secondary receptors by heparan sulfate-binding drug or antibody induces non-infectious uptake of human papillomavirus. J. Virol. 81:10970–10980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Selinka HC, Giroglou T, Nowak T, Christensen ND, Sapp M. 2003. Further evidence that papillomavirus particles exist in two distinct conformations. J. Virol. 77:12961–12967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Selinka HC, Giroglou T, Sapp M. 2002. Analysis of the infectious entry pathway of human papillomavirus type 33 pseudovirions. Virology 299:279–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Smith JL, Campos SK, Wandinger-Ness A, Ozbun MA. 2008. Caveolin-1 dependent infectious entry of human papillomavirus type 31 in human keratinocytes proceeds to the endosomal pathway for pH-dependent uncoating. J. Virol. 82:9505–9512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Spoden G, et al. 2008. Clathrin- and caveolin-independent entry of human papillomavirus type 16—involvement of tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (TEMs). PLoS One 3:e3313 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Suzuki J, Jin ZG, Meoli DF, Matoba T, Berk BC. 2006. Cyclophilin A is secreted by a vesicular pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 98:811–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Verdegem D, et al. 2011. Domain 3 of NS5A protein from the hepatitis C virus has intrinsic α-helical propensity and is a substrate of cyclophilin A. J. Biol. Chem. 286:20441–20454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Volpers C, Sapp M, Snijders PJ, Walboomers JM, Streeck RE. 1995. Conformational and linear epitopes on virus-like particles of human papillomavirus type 33 identified by monoclonal antibodies to the minor capsid protein L2. J. Gen. Virol. 76:2661–2667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Watashi K, et al. 2005. Cyclophilin B is a functional regulator of hepatitis C virus RNA polymerase. Mol. Cell 19:111–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wiethoff CM, Wodrich H, Gerace L, Nemerow GR. 2005. Adenovirus protein VI mediates membrane disruption following capsid disassembly. J. Virol. 79:1992–2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Yang R, et al. 2003. Cell surface-binding motifs of L2 that facilitate papillomavirus infection. J. Virol. 77:3531–3541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]