Abstract

The thermal transitions of fibrillar collagen are investigated with second-harmonic generation polarization anisotropy microscopy. Second-harmonic generation images and polarization anisotropy profiles of corneal stroma heated in the 35–80°C range are analyzed by means of a theoretical model that is suitable to probe principal intramolecular and interfibrillar parameters of immediate physiological interest. Our results depict the tissue modification with temperature as the interplay of three destructuration stages at different hierarchical levels of collagen assembly including its tertiary structure and interfibrillar alignment, thus supporting and extending previous findings. This method holds the promise of a quantitative inspection of fundamental biophysical and biochemical processes and may find future applications in real-time and postsurgical functional imaging of collagen-rich tissues subjected to thermal treatments.

Introduction

Collagen is the most abundant protein in the body and the main component of the extracellular matrix in connective tissue. Its tertiary structure involves three intertwined α-helices (triple helix) with the repetition of the peptide sequence lysine-proline-hydroxyproline, which is highly stabilized by interconnecting hydrogen bonds (1). Fibril-forming (fibrillar) collagen is the principal responsible for the structural and organizational framework of the skin dermis, blood vessels, bones, tendons, cornea, and other tissues. In this type of collagen, molecules are packed in a quarter-staggered array and connected by covalent cross-links to form fibrils that are a few to ∼100 nanometers in size (2,3). Some tissues are characterized by two or even three hierarchical levels of organization at progressively larger length scales beyond the fibril such as fibers and fascicles in tendons, and lamellae in corneal stroma.

Thermograms of tissue samples containing a collagen network and heated up to 90°C revealed a composite endothermic peak centered around 65°C, which portrays the denaturation of collagen as a sequence of concatenated subprocesses (4,5). Such a complexity calls for sensible and specific techniques to go deep into the fine dynamics of extracellular matrix disassembly. The pursuit of information down to the supramolecular scale has led various authors to use functional microscopic approaches. Relevant examples from the literature include polarized-light microscopy (6), atomic force microscopy (7), single- (8,9) and multiphoton (10) fluorescence microscopy, and second-harmonic generation (SHG) microscopy (11–14). Among others, the latter holds the promise of high contrast, collagen specificity, high resolution, and minimal invasiveness (15,16), which is drawing interest for the analysis of tissue disorders in basic investigations and clinical pathology (17–24). SHG is a frequency-doubling optical scattering process, which stems from coherent interaction of tightly focused ultrashort light pulses with organized ensembles of noncentrosymmetric targets with significant hyperpolarizability (25,26), including biological components such as myosin, cellulose, microtubules, and collagen (27–30).

Intense SHG signals are particularly associated with the regular arrangement of collagen superstructures, which may be exploited for functional imaging with high specificity and contrast for this protein without the need for dye labeling (31). The importance of the overall organization of collagen for its SHG conversion is typified in its dependence on temperature. When exceeding a loose temperature threshold, there begins a progressive decrease in the SHG intensity from collagen, which has been ascribed to the onset of degradation of its architecture with loss of scattering coherence (8,32,33). Proposals for using the modulation of SHG intensity to detect collagen denaturation have been reported in a number of publications on different tissues, including tendons (8,11), skin (13), and cornea (34).

Because the SHG intensity is governed by the mutual orientation between the exciting electric field and the orientational distribution of the emitters within the focal volume, the implementation of SHG microscopy with a polarization setup may provide unique morphofunctional details (35–42). The modulation of the laser polarization has already proven useful to investigate different biological phenomena such as fibrillogenesis (37) and muscle contraction (27), as well as pathological disorders such as osteogenesis imperfecta (43) and cancer (44). In a recent work, we have proposed an empirical analysis of both SHG micrographs and SHG polarization anisotropy (SPA) profiles to parameterize the damage induced by low-power continuous-wave diode laser treatment of corneal stroma (45). In this contribution, we aim to exploit the full power of the SPA approach to resolve the mechanism of thermal denaturation of fibrillar collagen into its fundamental molecular steps. We implement a theoretical model based on the simulation of the SHG signal from three-dimensional constructs of emitters to retrieve principal parameters of the molecular and supramolecular assembly of collagen.

Materials and Methods

Sample treatment

The investigation of collagen transitions was carried out on corneal stroma, which was taken as a convenient model of collagenous tissue due to its regular distribution of parallel collagen fibrils and scarce presence of cellular components (46,47). Forty corneal buttons were excised from freshly enucleated (4 h postmortem) eyes of pigs aged 9–11 months. Transparency and integrity of the corneal specimens were inspected under a stereomicroscope before utilization. Samples were then immersed in a water bath for 4 min to reach thermal equilibrium (48). Temperature values were 35 (control), 40, 45, 50, 55, 60, 65, 70, 75, and 80°C. Immediately after the thermal treatment, samples were sliced in 1-mm-thick cross sections with a razor blade and stored under formalin for no longer than 52 h until acquisition of the SHG images. Three samples per temperature were analyzed.

Portions of thermally treated corneal slices were then processed for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) measurements (49). In brief, samples were fixed in 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline and cut into 1 mm2 pieces, which were postfixed in 1% (w/v) osmium tetroxide and, after sequential dehydration, infiltrated in epoxy resin. Ultrathin (60–90-nm thick) sections were cut, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined with an electron microscope (CM-12; Philips Industries, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). Representative micrographs of stromal regions were taken from each specimen.

SHG microscopy system

SHG images were acquired with an inverted laser scanning microscope equipped with a mode-locked femtosecond Ti:Sapphire laser (Mira 900; Coherent, Santa Clara, CA) emitting at 880 nm, as described in detail in Nucciotti et al. (27) and Cicchi et al. (50). The beam was focused onto the sample by a 50× 0.95 NA oil immersion objective (Plan-Apo, 0.35 mm WD; Nikon Instruments, Tokyo, Japan), and the forward-scattered light was collected using a 60× 1.00 NA-long-working-distance water immersion objective (Plan-Fluor, 2 mm WD; Nikon Instruments). SHG light was filtered by a narrow band-pass optical filter centered at one-half the excitation wavelength (440 ± 5 nm, Z440BP; Chroma Technology, Rockingham, VT) placed in front of a photomultiplier tube (H7713; Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan).

A variable linear polarization of the excitation light was accomplished through a rotating polarization system, comprising a fixed linear polarizer and quarter-wave plate to achieve circular polarization and correct polarization ellipticity, and a linear polarizer mounted on a motorized rotation stage to modulate the alignment between the exciting field and biological sample (45). The measured polarization ellipticity after the objective (without rotating polarizer and sample) introduced by optical components was within 3%. To minimize detrimental effects of the tissue anisotropy on the polarization of the excitation beam such as collagen birefringence, the imaging depth from the tissue surface was set to ∼5 μm. In this connection, we note that the peculiar morphology of corneal stroma with its stack of lamellae of different orientation is known to relieve the tissue birefringence (51). In addition, the loss of interfibrillar alignment at high temperatures is expected to mitigate these effects in the regime of our principal interest. For all imaging not intended for the polarization analysis, the excitation light was circularly polarized. Image areas of 60 × 60 μm2 (0.12 μm/pixel) were scanned for the analysis.

Theoretical and analytical background

The dependence of the SHG signal on the polarization of the exciting light was exploited to achieve information on the architecture of the collagen network. For each temperature and field of view, images were acquired at different polarization angles through the turn at steps of 10°. Then SPA profiles were reconstructed by retrieving the SHG intensity from specific points as a function of polarization angle. Here we imagine that the laser focal volume encloses a statistical ensemble of thousands of fibrils, which consist of stacks of parallel collagen molecules with their individual axes aligned along their fibrillar axis (3,52).

Before reconstruction of the SPA profiles, data were filtered to select those points with the average axes of the collagen molecules in the plane orthogonal to the optical axis of the microscope (termed the polarization plane hereafter). This filtration was implemented by noting that the SHG intensity undergoes a monotonic decrease with the altitude angle of the molecular axes from the polarization plane, as it is implied in the model below (see Fig. 1 B) and in Ratto et al. (53). Thus by assuming all possible orientations of the molecular axes to be represented in every 3600 μm2 field of view and after de-spiking, we took those pixels (∼5000 per image, see the Supporting Material for additional detail) with highest intensity and achieved the due filtration with an estimated tolerance on the altitude angle of ∼1°. Then the corresponding SPA profiles were processed and realigned to begin with the average molecular axes orthogonal to the drive field at α = 0°, where the angle α is taken to describe the polarization direction in the lab frame. This condition was fulfilled after rephasing the polarization profiles to set their absolute minima at α = 0° in agreement with the model below and with Reiser et al. (40) and Matteini et al. (45). These preliminary steps were performed to simplify the data analysis, as it shall be mentioned, by application of a model that combines geometrical and physical concepts from the literature (37,54–59).

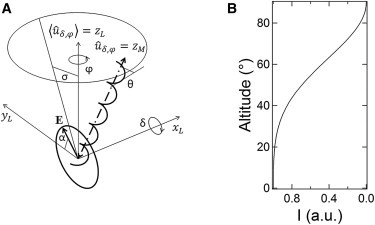

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic representation of the geometrical framework behind the model formulation. A collagen molecule is represented as a helix for simplicity. (B) Plot of the altitude angle from the polarization plane (i.e., inclination δ with azimuth φ = 90°) of a collagen molecule versus forward-scattered SHG intensity averaged over α, as it follows from the model in the text.

Briefly, let us start with a description of the geometrical framework behind this model (Fig. 1 A). In the lab frame, light is taken to propagate along (optical axis, L for lab) and the average orientation of the molecular axes to be along (the realization of this configuration is enabled by the preliminary filtration and realignment). However, the individual molecules within the laser focal volume are allowed to be misaligned from . This misalignment is described by a first rotation by the angle δ about and then φ about , which are inclination and azimuth in a spherical coordinate system with zenith . These angles are assumed to be distributed with a certain probability ℘(δ,φ) such that . In the lab frame, the incident electric field is described by .

To exploit the formalism in common use for the SHG from collagen molecules, we resort to another frame integral with their principal axes. Therefore, we need to start with the individual molecule with its particular misalignment given by δ and φ, and then integrate over all molecules that contribute to the SHG signal. In the individual molecule frame, the incident electric field reads (M for molecule), with the rotation matrix

This electric field generates a second-harmonic polarization, which is

The polarization

originates the SHG signal, which may be gauged along any direction in the lab frame. Now we integrate over all individual molecules inside the laser focal volume to obtain a coherent dipole moment as

Finally, the SHG intensity in the forward direction, i.e., along , is given by

(55,58). The expansion of this framework allows us to describe the SHG intensity as an explicit function of the interfibrillar disorganization and intramolecular configuration, which are the parameters of our principal interest. Indeed the probability ℘(δ,φ) represents the distribution of molecular axes, which relates to the interfibrillar disorganization because of the alignment of molecules in fibrils (3,52). The tensor χ(2)M encodes the intramolecular configuration of SHG emitters, as it is extensively discussed in Plotnikov et al. (54), Tiaho et al. (55), and Su et al. (58).

Without pretension to devise an accurate portrayal of interfibrillar relations, we take the angles δ and φ to follow a uniform distribution within a spread σ. In practice, the angle σ provides an effective parameterization of the fibrils misalignment. Thus,

and H is the Heaviside step function (see the Supporting Material for a brief discussion of relevance and rationale behind this choice). Next, we take inspiration from Su et al. (58) to write the second-order susceptibility tensor for collagen molecules in their frame, i.e., with their principal axes along . According to the literature (54,58), the symmetry of these molecules leaves four independent tensor elements only, i.e.,

and

whereas the others are null. In turn, these elements may be devised in terms of the internal structure of the collagen molecules as

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

(58). Here A comprises the density and hyperpolarizability of peptide bonds, which are the main molecular SHG emitters, and θ is a pitch angle that describes the inclination of these peptide bonds in their α-helix with respect to the principal axis of the collagen molecule (55). The small contribution from methylene groups of proline and hydroxyproline is overlooked. Here we focus on possible transformations of the tertiary structure and disregard alterations of the primary structure of collagen up to the late steps of its denaturation. Therefore we neglect the dependence of A on temperature (we note that according to Sun et al. (10) the molecular density keeps constant with temperature) and take θ to measure the structural conformation and extent of thermal modification of the collagen molecule.

Once these notions are implemented in the model, happens to depend on α as well as σ, A, and θ, with the exact value also scaling with various factors such as fundamental constants and experimental parameters (distances, detection efficiencies, etc.). For the sake of convenience, these factors may be incorporated into A. With all these precepts, is written as an explicit function of α, which may be used to fit the experimental data with one temperature-independent parameter, i.e., A, and only another two temperature-dependent parameters, i.e., σ and θ (see the Appendix for details).

For each temperature, we defined an experimental polarization profile as the average of 100 polarization profiles taken from individual points after filtration and rephasing. These experimental data at different temperatures were fitted with a fixed value for A and variable values for σ and θ.

We note that this overall framework does not inherently require the function ℘(δ,φ) to be compliant with , which reflects our preliminary filtration and realignment. Conversely may be used as another two fit parameters for a complete three-dimensional mapping of the fibril orientations without any preliminary operation. However, this approach prevents the treatment of average polarization profiles. Here we declined this choice, which would have entailed too-low signal/noise ratio and too many fit parameters at the expense of a poor determination of the angles σ and θ of our principal interest.

Results and Discussion

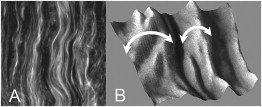

SHG images of control samples (Fig. 2) reveal waving superstructures 1 ÷ 4.5-μm large composed of ∼0.5-μm collagen bundles. The former are ascribed to corneal lamellae with fibrils that lay in and out of the image plane, which coincides with the polarization plane and originates the characteristic pattern of light and dark stripes respectively, whereas the latter corresponds to the minimum resolvable distance of the microscope as it is discussed in Matteini et al. (45).

Figure 2.

(A) Example SHG image of a control corneal sample (50 × 50 μm2) showing 0.5-μm collagen bundles running parallel within superstructures, which are ascribed to stromal lamellae with fibrils laying in and out of the image plane, as further evidenced in (B) the three-dimensional rendering of a selected 5 × 5 μm2 area.

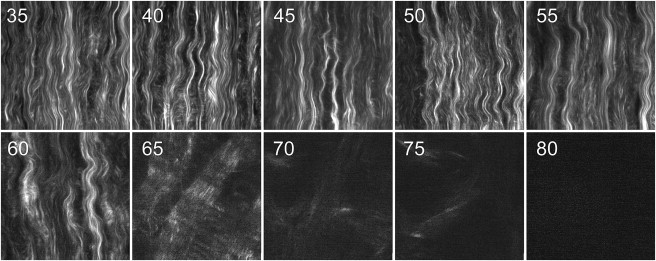

This arrangement does not undergo substantial changes up to 50°C despite a modest decrease of SHG signal. Instead significant modifications of the collagen network emerge from above 55°C, accompanied by a sudden reduction of SHG intensity, which amounts to as much as two orders of magnitude at 80°C (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4 A and see the Supporting Material for a brief discussion of signal/noise ratios). These results agree with previous studies in which a similar signal drop was observed and taken as evidence of some collagen network destructuration (8,13,32).

Figure 3.

SHG micrographs of corneal samples heated in a water-bath at different temperatures (reported in °C in the top-left corner of each image). Each image corresponds to an area of 60 × 60 μm2.

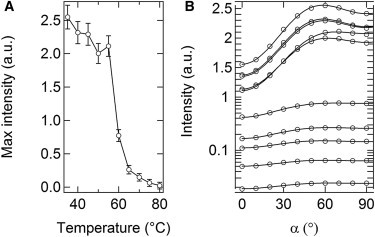

Figure 4.

(A) Modulation of SHG intensities at increasing temperatures. (B) SPA profiles (average of n = 100 profiles from single image pixels): experimental data (circles) and analytical fits (lines) in the control, 40, 45, 50, 55, 60, 65, 70, 75 and 80°C samples (in the order which may be inferred from panel A, note that the intensity axis is linear above and logarithmic below unity).

To gain further detail on these changes, we compared SPA profiles as a function of polarization angle of the exciting light over a 0 ÷ 180° range. The variation of SHG intensity exhibits a typical pattern of alternating minima and maxima (Fig. 4 B, where data were folded into one quadrant). Absolute minima correspond to a condition of orthogonality between linear polarization of the exciting field and average principal axis of the collagen fibrils. The modulation of these profiles reflects the anisotropy content of the sample and may be exploited to derive relevant parameters of physiological interest. Here we implemented the theoretical model described above to fit the polarization data and quantify the rate of organization at different hierarchical levels of fibrillar collagen. The fit of the data at 35°C was performed with three free parameters, i.e., A, σ, and θ. Instead, A was kept constant for the successive analysis, and so the data at temperatures exceeding 35°C were fitted with two free parameters only, i.e., σ and θ. Despite the strictness of these constraints, the experimental and theoretical profiles are in excellent agreement (Fig. 4 B), which provides a validation of our analytical method.

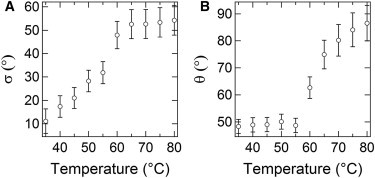

An evaluation of the angular misalignment of collagen fibrils (σ) at successive stages of thermal treatment is displayed in Fig. 5 A. The angular spread is found to progressively increase between 35 and 60°C and then take a constant value of ∼52°, which denotes the coexistence of orthogonal fibrils. We note that the modification of fibrillar misalignment develops well below 65°C, which is the threshold for collagen denaturation (60), and thus requires another interpretation. Although a complete description of this phenomenon goes beyond the scope of this study, we propose that an increase of the angular spread may correlate with structural modifications of interfibrillar proteoglycan bridges that underpin the connective network.

Figure 5.

(A) Values of the angular spread among collagen fibrils (σ) and (B) orientation of the α-chains within the triple-helix envelope (θ) versus temperature.

These glycoproteins feature long glycosaminoglycan filaments that, under homeostatic conditions, secure the mutual positions of adjacent collagen fibrils by interchain interactions (61). These interactions were shown to weaken already below 60°C by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (62) and nuclear magnetic resonance (61) under in vitro conditions, which may play a principal role in the loss of regularity of the interfibrillar disposition. Indeed this picture is coherent with the increase in angular spread shown in Fig. 5 A. The possibility of low-temperature modifications of noncollagenous species impairing the regular architecture of the native collagen network is in agreement with our previous observation of a tissue transformation without loss of integrity of individual collagen fibrils, which was induced by laser surgery at temperatures not exceeding 65°C (49,63).

The dependence of the SHG intensity on the polarization angle also gives insight into subtle modifications occurring below the fibrillar level. In particular, we investigated the angle that represents the average orientation of the peptide groups of collagen molecules in their α-helix envelopes. The plot of θ versus temperature (Fig. 5 B) shows values around (48 ± 3)° for temperatures up to 55°C, which is in agreement with the native helical pitch of collagen as found by x-ray diffraction (64) and former SHG analysis (55,58). At higher temperatures, we estimated a larger variance, which may reflect the incidence of molecular disorder and progressive deterioration of the triple helices. Above all θ is found to gradually increase up to (87 ± 7)° at 80°C. This substantial increase in pitch angle may account for a collapse of the triple-helix structure (including a longitudinal shortening and a consequent lateral swelling), which characterizes the fibrillar protein unfolding in denaturation events featuring a helix-to-coil transformation (60,65–67).

The variation of θ from 48 to 87° corresponds to a lateral swelling that may be roughly quantified at ∼30%, in qualitative agreement with previous reports (68). The observed variation of θ may find its biochemical basis in the breakage of intramolecular hydrogen bonds (69), which keep the triple helix of collagen together, eventually leading to a contraction along the fibril axis (70,71). On the other hand, the complete loss of SHG signal above 80°C may be contributed by the breakdown of the regular peptide assembly and substantial loss of fibrillar integrity. The latter fits well into the last step of collagen denaturation, which was already hypothesized to result from hydrolysis of mostly covalent cross-links between and within collagen molecules, ultimately leading to a complete disintegration of the collagen fibrils at a microscale and full homogenization of the connective tissue, as it becomes observable over a macroscale (72–74).

Conclusions

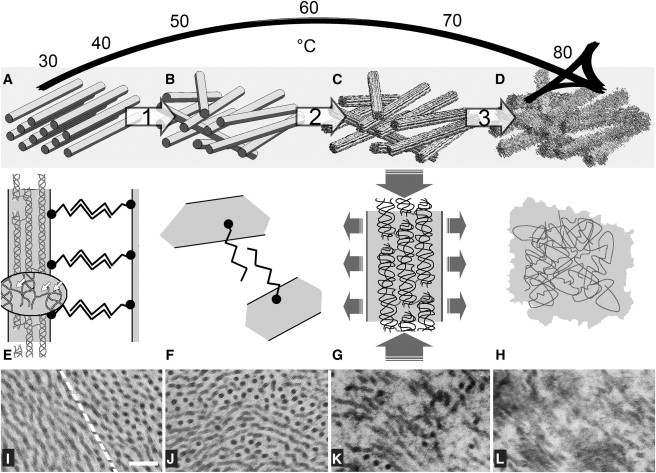

A careful analysis of SPA profiles depicted the thermal denaturation of fibrillar corneal collagen as the interplay of three main events at different hierarchical levels of the collagen architecture as summarized in Fig. 6, A–D, and detailed in Fig. 6, E–H. A TEM check at different stages of thermal treatment was carried out to support the SHG investigation as reported in Fig. 6, I–L:

Step 1. The observation of a progressive variation in the interfibrillar misalignment suggested a first low-temperature transition, probably affecting noncollagenous species and impairing the supramolecular assembly of collagen from just above physiological temperature.

Step 2. A significant variation in the triple-helix pitch angle beyond 55°C was found to be in good agreement with the onset of molecular unfolding and fibrillar contraction. This came with a substantial decrease in SHG intensity.

Step 3. The SHG intensity progressively reduced to background levels upon loss of the cross-linking network at temperatures exceeding 80°C.

Figure 6.

Proposed three-step model of collagen denaturation as deduced by SPA analysis (A–H) and supported by TEM (I–L). (A) At control temperature, collagen fibrils are regularly organized in a parallel arrangement with similar interfibrillar spacing provided by proteoglycan bridges between fibrils (E). Each fibril features a regular quarter-staggered packing of collagen molecules built up by intramolecular and intermolecular covalent bonds (indicated in the magnification by arrows). (I) Typical appearance of control corneal stroma at the border (dashed line) between two orthogonal lamellae. (B, F, and J) As temperature rises, the regular fibrillar arrangement is impaired (step 1) as suggested by the increase of the angular spread among fibrils, which is ascribed to the breaking of interfibrillar bridges. (G) Starting from 60°C, higher values of the triple-helix pitch-angle fit with a progressive collapse of the collagen molecule (step 2) due to the hydrolysis of the intramolecular H-bonds and responsible for a shrinkage parallel to the axis of the fibril. (C and K) As a consequence, fibrillar edges appear frayed and the average fibrillar diameter increases. (H) The substantial loss of SHG signal beyond 80°C suggests a full breakdown of the regular peptide assembly (step 3) due to the hydrolysis of covalent cross-links between and within collagen molecules, causing full denaturation of collagen and homogenization of the tissue (D and L). Panels E–H are not to scale; panels I–L: bar = 200 nm.

Our theoretical and analytical framework proved effective to identify multistep thermal transitions of fibrillar collagen in a model connective tissue. This study suggests that the SPA analysis may provide crucial and quantitative information about the collagen network, which is not available from mere intensity measurements. The possibility to track molecular and supramolecular collagen modifications without the need for invasive and time-consuming histological and labeling procedures adds interest for this approach in fundamental research, as a complementary method with respect to conventional ultrastructural techniques such as electron microscopy and x-ray diffraction. Moreover, this analysis may hold the promise of future applications in the clinical context such as to monitor the heat damage induced in connective tissues during thermal surgeries with high sensitivity and to follow the restoration of the collagen architecture during the postoperative healing period. We anticipate that a minimally invasive measurement of collagen modifications may become relevant well beyond thermal surgeries for a broad variety of pathological and accidental conditions.

Acknowledgments

This work has been partially supported by the FP7 NoE Photonics 4 Life and by the NANO-CHROM Project of the Health Board of Tuscany.

Appendix

In this Appendix, we give the explicit formulation of the analytical function that was used to fit the experimental data,

with

The value ε is a constant background and accounts for diffuse light intensity. The dependence on the fit parameter σ is explicitly stated in these equations. Instead, the fit parameters A and θ are embedded in the various second-order susceptibility tensor elements as in Eqs. 1–4. We note that, as σ tends to zero, these equations turn into to the two-dimensional model in common use to describe fibrils with their axes flat in the polarization plane (37,55,57,59,75).

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Brodsky B., Persikov A.V. Molecular structure of the collagen triple helix. Adv. Protein Chem. 2005;70:301–339. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)70009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ottani V., Martini D., Raspanti M. Hierarchical structures in fibrillar collagens. Micron. 2002;33:587–596. doi: 10.1016/s0968-4328(02)00033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gautieri A., Vesentini S., Buehler M.J. Hierarchical structure and nanomechanics of collagen microfibrils from the atomistic scale up. Nano Lett. 2011;11:757–766. doi: 10.1021/nl103943u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kampmeier J., Radt B., Brinkmann R. Thermal and biomechanical parameters of porcine cornea. Cornea. 2000;19:355–363. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200005000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flandin F., Buffevant C., Herbage D. A differential scanning calorimetry analysis of the age-related changes in the thermal stability of rat skin collagen. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1984;791:205–211. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(84)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maitland D.J., Walsh J.T.J., Jr. Quantitative measurements of linear birefringence during heating of native collagen. Lasers Surg. Med. 1997;20:310–318. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9101(1997)20:3<310::aid-lsm10>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bozec L., Odlyha M. Thermal denaturation studies of collagen by microthermal analysis and atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 2011;101:228–236. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Theodossiou T., Rapti G.S., Yova D. Thermally induced irreversible conformational changes in collagen probed by optical second harmonic generation and laser-induced fluorescence. Lasers Med. Sci. 2002;17:34–41. doi: 10.1007/s10103-002-8264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossi F., Matteini P., Pini R. Monitoring thermally-induced phase transitions in porcine cornea with the use of fluorescence micro-imaging analysis. Opt. Express. 2007;15:11178–11184. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.011178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun Y., Chen W.L., Dong C.Y. Investigating mechanisms of collagen thermal denaturation by high resolution second-harmonic generation imaging. Biophys. J. 2006;91:2620–2625. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.085902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin S.J., Hsiao C.Y., Dong C.Y. Monitoring the thermally induced structural transitions of collagen by use of second-harmonic generation microscopy. Opt. Lett. 2005;30:622–624. doi: 10.1364/ol.30.000622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Theodossiou T.A., Thrasivoulou C., Becker D.L. Second harmonic generation confocal microscopy of collagen type I from rat tendon cryosections. Biophys. J. 2006;91:4665–4677. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.093740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin M.G., Yang T.L., Lin S.J. Evaluation of dermal thermal damage by multiphoton autofluorescence and second-harmonic-generation microscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 2006;11:064006. doi: 10.1117/1.2405347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hovhannisyan V.A., Su P.J., Dong C.Y. Quantifying thermodynamics of collagen thermal denaturation by second harmonic generation imaging. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009;94:233902. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zipfel W.R., Williams R.M., Webb W.W. Live tissue intrinsic emission microscopy using multiphoton-excited native fluorescence and second harmonic generation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:7075–7080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0832308100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zoumi A., Yeh A., Tromberg B.J. Imaging cells and extracellular matrix in vivo by using second-harmonic generation and two-photon excited fluorescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:11014–11019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172368799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campagnola P.J., Dong C.Y. Second harmonic generation microscopy: principles and applications to disease diagnosis. Laser Photon. Rev. 2011;5:13–26. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strupler M., Hernest M., Schanne-Klein M.C. Second harmonic microscopy to quantify renal interstitial fibrosis and arterial remodeling. J. Biomed. Opt. 2008;13:054041. doi: 10.1117/1.2981830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morishige N., Wahlert A.J., Jester J.V. Second-harmonic imaging microscopy of normal human and keratoconus cornea. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007;48:1087–1094. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cicchi R., Crisci A., Pavone F.S. Time- and spectral-resolved two-photon imaging of healthy bladder mucosa and carcinoma in situ. Opt. Express. 2010;18:3840–3849. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.003840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeh A.T., Kao B., Tromberg B.J. Imaging wound healing using optical coherence tomography and multiphoton microscopy in an in vitro skin-equivalent tissue model. J. Biomed. Opt. 2004;9:248–253. doi: 10.1117/1.1648646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strupler M., Pena A.M., Schanne-Klein M.C. Second harmonic imaging and scoring of collagen in fibrotic tissues. Opt. Express. 2007;15:4054–4065. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.004054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cicchi R., Kapsokalyvas D., Pavone F.S. Scoring of collagen organization in healthy and diseased human dermis by multiphoton microscopy. J. Biophoton. 2010;3:34–43. doi: 10.1002/jbio.200910062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cicchi R., Vogler N., Pavone F.S. From molecular structure to tissue architecture: collagen organization probed by SHG microscopy. J. Biophoton. 2012 doi: 10.1002/jbio.201200092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moreaux L., Sandre O., Mertz J. Coherent scattering in multi-harmonic light microscopy. Biophys. J. 2001;80:1568–1574. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76129-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gauderon R., Lukins P.B., Sheppard C.J. Optimization of second-harmonic generation microscopy. Micron. 2001;32:691–700. doi: 10.1016/s0968-4328(00)00066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nucciotti V., Stringari C., Pavone F.S. Probing myosin structural conformation in vivo by second-harmonic generation microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:7763–7768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914782107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Psilodimitrakopoulos S., Petegnief V., Loza-Alvarez P. Estimation of the effective orientation of the SHG source in primary cortical neurons. Opt. Express. 2009;17:14418–14425. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.014418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Recher G., Rouède D., Tiaho F. Three distinct sarcomeric patterns of skeletal muscle revealed by SHG and TPEF microscopy. Opt. Express. 2009;17:19763–19777. doi: 10.1364/OE.17.019763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campagnola P.J., Millard A.C., Mohler W.A. Three-dimensional high-resolution second-harmonic generation imaging of endogenous structural proteins in biological tissues. Biophys. J. 2002;82:493–508. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75414-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams R.M., Zipfel W.R., Webb W.W. Interpreting second-harmonic generation images of collagen I fibrils. Biophys. J. 2005;88:1377–1386. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.047308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim B.M., Eichler J., Da Silva L.B. Collagen structure and nonlinear susceptibility: effects of heat, glycation, and enzymatic cleavage on second harmonic signal intensity. Lasers Surg. Med. 2000;27:329–335. doi: 10.1002/1096-9101(2000)27:4<329::aid-lsm5>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lo W., Chang Y.L., Dong C.Y. Multimodal, multiphoton microscopy and image correlation analysis for characterizing corneal thermal damage. J. Biomed. Opt. 2009;14:054003. doi: 10.1117/1.3213602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tan H.Y., Teng S.W., Dong C.Y. Characterizing the thermally induced structural changes to intact porcine eye, part 1: second harmonic generation imaging of cornea stroma. J. Biomed. Opt. 2005;10:054019. doi: 10.1117/1.2012987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yasui T., Tohno Y., Araki T. Determination of collagen fiber orientation in human tissue by use of polarization measurement of molecular second-harmonic-generation light. Appl. Opt. 2004;43:2861–2867. doi: 10.1364/ao.43.002861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stoller P., Celliers P.M., Rubenchik A.M. Quantitative second-harmonic generation microscopy in collagen. Appl. Opt. 2003;42:5209–5219. doi: 10.1364/ao.42.005209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stoller P., Reiser K.M., Rubenchik A.M. Polarization-modulated second harmonic generation in collagen. Biophys. J. 2002;82:3330–3342. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75673-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plotnikov S., Juneja V., Campagnola P.J. Optical clearing for improved contrast in second harmonic generation imaging of skeletal muscle. Biophys. J. 2006;90:328–339. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.066944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chu S.W., Chen S.Y., Sun C.K. Studies of χ2/χ3 tensors in submicron-scaled bio-tissues by polarization harmonics optical microscopy. Biophys. J. 2004;86:3914–3922. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.034595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reiser K.M., Bratton C., Lotz J. Quantitative analysis of structural disorder in intervertebral disks using second harmonic generation imaging: comparison with morphometric analysis. J. Biomed. Opt. 2007;12:064019. doi: 10.1117/1.2812631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Psilodimitrakopoulos S., Artigas D., Loza-Alvarez P. Quantitative discrimination between endogenous SHG sources in mammalian tissue, based on their polarization response. Opt. Express. 2009;17:10168–10176. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.010168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vanzi F., Sacconi L., Pavone F.S. Protein conformation and molecular order probed by second-harmonic-generation microscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 2012;17:060901. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.17.6.060901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nadiarnykh O., Plotnikov S., Campagnola P.J. Second harmonic generation imaging microscopy studies of osteogenesis imperfecta. J. Biomed. Opt. 2007;12:051805. doi: 10.1117/1.2799538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han X., Burke R.M., Brown E.B. Second harmonic properties of tumor collagen: determining the structural relationship between reactive stroma and healthy stroma. Opt. Express. 2008;16:1846–1859. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.001846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matteini P., Ratto F., Pini R. Photothermally-induced disordered patterns of corneal collagen revealed by SHG imaging. Opt. Express. 2009;17:4868–4878. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.004868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han M., Giese G., Bille J. Second harmonic generation imaging of collagen fibrils in cornea and sclera. Opt. Express. 2005;13:5791–5797. doi: 10.1364/opex.13.005791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olivier N., Aptel F., Beaurepaire E. Harmonic microscopy of isotropic and anisotropic microstructure of the human cornea. Opt. Express. 2010;18:5028–5040. doi: 10.1364/OE.18.005028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Welch A.J., van Gemert M.J.C. Plenum Press; New York: 1995. Optical-Thermal Response of Laser-Irradiated Tissue. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matteini P., Rossi F., Pini R. Microscopic characterization of collagen modifications induced by low-temperature diode-laser welding of corneal tissue. Lasers Surg. Med. 2007;39:597–604. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cicchi R., Sacconi L., Pavone F.S. Multidimensional custom-made non-linear microscope: from ex-vivo to in-vivo imaging. Appl. Phys. B. 2008;92:359–365. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Knighton R.W., Huang X.R. Linear birefringence of the central human cornea. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002;43:82–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fratzl P. Springer; New York: 2008. Collagen: Structure and Mechanics. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ratto F., Matteini P., Pini R. Analysis of second-harmonic generation polarization profiles: an attempt to devise a complete three-dimensional model. CNR Tech. Scient. Res. Rep. 2009;1:113–120. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Plotnikov S.V., Millard A.C., Mohler W.A. Characterization of the myosin-based source for second-harmonic generation from muscle sarcomeres. Biophys. J. 2006;90:693–703. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.071555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tiaho F., Recher G., Rouède D. Estimation of helical angles of myosin and collagen by second harmonic generation imaging microscopy. Opt. Express. 2007;15:12286–12295. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.012286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Odin C., Le Grand Y., Baffet G. Orientation fields of nonlinear biological fibrils by second harmonic generation microscopy. J. Microsc. 2008;229:32–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2007.01868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Psilodimitrakopoulos S., Santos S.I., Loza-Alvarez P. In vivo, pixel-resolution mapping of thick filaments' orientation in nonfibrillar muscle using polarization-sensitive second harmonic generation microscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 2009;14:014001. doi: 10.1117/1.3059627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Su P.J., Chen W.L., Dong C.Y. Determination of collagen nanostructure from second-order susceptibility tensor analysis. Biophys. J. 2011;100:2053–2062. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moreaux L., Sandre O., Mertz J. Membrane imaging by second-harmonic generation microscopy. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B. 2000;17:1685–1694. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wright N.T., Humphrey J.D. Denaturation of collagen via heating: an irreversible rate process. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2002;4:109–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.4.101001.131546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scott J.E., Heatley F. Biological properties of hyaluronan in aqueous solution are controlled and sequestered by reversible tertiary structures, defined by NMR spectroscopy. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3:547–553. doi: 10.1021/bm010170j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matteini P., Dei L., Pini R. Structural behavior of highly concentrated hyaluronan. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:1516–1522. doi: 10.1021/bm900108z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Matteini P., Sbrana F., Pini R. Atomic force microscopy and transmission electron microscopy analyses of low-temperature laser welding of the cornea. Lasers Med. Sci. 2009;24:667–671. doi: 10.1007/s10103-008-0617-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Beck K., Brodsky B. Supercoiled protein motifs: the collagen triple-helix and the α-helical coiled coil. J. Struct. Biol. 1998;122:17–29. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1998.3965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Asiyo-Vogel M.N., Brinkmann R., Vogel A. Histologic analysis of thermal effects of laser thermokeratoplasty and corneal ablation using Sirius-red polarization microscopy. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 1997;23:515–526. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(97)80208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McClain P.E., Wiley E.R. Differential scanning calorimeter studies of the thermal transitions of collagen. Implications on structure and stability. J. Biol. Chem. 1972;247:692–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Harris J.L., Humphrey J.D. Kinetics of thermal damage to a collagenous membrane under biaxial isotonic loading. IEEE T. Biomed. Eng. (NY) 2004;51:371–379. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2003.820375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Timberlake G., Patmore A., Marshall J. Thermal and infrared diode-laser effects on indocyanine green treated corneal collagen. Proc. SPIE. 1993;1882:244–253. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miles C.A., Bailey A.J. Thermally labile domains in the collagen molecule. Micron. 2001;32:325–332. doi: 10.1016/s0968-4328(00)00034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miles C.A., Burjanadze T.V., Bailey A.J. The kinetics of the thermal denaturation of collagen in unrestrained rat tail tendon determined by differential scanning calorimetry. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;245:437–446. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Allain J.C., Le Lous M., Maroteaux P. Isometric tensions developed during the hydrothermal swelling of rat skin. Connect. Tissue Res. 1980;7:127–133. doi: 10.3109/03008208009152104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Miles C.A., Bailey A.J. Thermal denaturation of collagen revisited. Proc. Indian Acad. Sci. (Chem. Sci.). 1999;111:71–80. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thomsen S. Pathologic analysis of photothermal and photomechanical effects of laser-tissue interactions. Photochem. Photobiol. 1991;53:825–835. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1991.tb09897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.le Lous M., Flandin F., Allain J.C. Influence of collagen denaturation on the chemorheological properties of skin, assessed by differential scanning calorimetry and hydrothermal isometric tension measurement. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1982;717:295–300. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(82)90182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moreaux L., Sandre O., Mertz J. Membrane imaging by simultaneous second-harmonic generation and two-photon microscopy. Opt. Lett. 2000;25:320–322. doi: 10.1364/ol.25.000320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.