Abstract

Background

In the United States, the mortality rate from traffic injury is higher in rural and in southern regions, for reasons that are not well understood.

Methods

For 1754 (56%) of the 3142 US counties, we obtained data allowing for separation of the deaths/population (D/P) rate into deaths/injury (D/I), injuries/crash (I/C), crashes/exposure (C/E), and exposure/population (E/P), with exposure measured as vehicle miles traveled. A “decomposition method” proposed by Li and Baker was extended to study how the contributions of these components were affected by three measures of rural location, as well as southern location.

Results

The method of Li and Baker extended without difficulty to include non-binary effects and multiple exposures. D/I was by far the most important determinant in the county-to-county variation in D/P, and accounted for the greatest portion of the rural/urban disparity. After controlling for the rural effect, I/C accounted for most of the southern/northern disparity.

Conclusions

The increased mortality rate from traffic injury in rural areas can be attributed to the increased probability of death given that a person has been injured, possibly due to challenges faced by emergency medical response systems. In southern areas, there is an increased probability of injury given that a person has crashed, possibly due to differences in vehicle, road, or driving conditions.

Keywords: Traffic, mortality, decomposition, rural, south

INTRODUCTION

Residents of rural areas are more likely than residents of urban areas to die from motor vehicle crashes (MVC).[1] Many explanations have been proposed for this disparity, including variation in distance traveled (exposure), crash severity, and emergency medical care.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] However, the relative importance of these factors is not clear. Furthermore, there still appears to be an increased mortality rate in the southern United States even after accounting for the rural/urban disparity.[6, 7]

One potential method to study factor importance is through partitioning the traffic mortality rate using a form of “decomposition”. Li and Baker [8] investigated which component was most responsible for the male/female discrepancy in bicycle related mortality using the equation

This approach of separating the population death rate into components has been adapted by others to study how traffic mortality is affected by age and sex.[9, 10, 11, 12] Zwerling and colleagues[13] also used this method to study the effect of rural location on traffic mortality, stratified by age and sex. They concluded that the greatest rural-urban disparity was in the risk of death given that a person had been injured.

In this study we analyze US county-level data to gain further insight into the nature of the rural-urban and southern-northern MVC mortality rate disparities in order to better understand which factors are most influential. While Zwerling et al[13] dichotomously compared rural to urban areas, we use aggregated county data to compare rates across the rural-urban continuum. Furthermore, we extend the analytic methods of Li and colleagues[9, 14] beyond a simple dichotomous exposure and show how they can be used for ordinal or continuous exposures, as well as for multiple factors. Finally, we intend to add clarity to the somewhat confusing literature about how the decomposition of rates has been used in epidemiology.

METHODS

Data Sources

County-level data included the numbers of fatalities from MVC, numbers of non-fatal injuries from MVC, total number of MVC, population estimates, land area, Rural-Urban Continuum Codes (RUCC), and vehicle miles traveled (VMT). Data were collected and analyzed for both 2007 (the most recent year with available data) and 1999 (the earliest year with available data). A database of all the 3142 US counties was created for our analysis, and is provided as an on-line appendix to this manuscript.

The county-level data were obtained from multiple sources. Non-fatal injuries and total vehicle crashes by county were obtained from individual state websites (listed in the on-line appendix). MVC fatalities by county were obtained from the Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS). The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) produces FARS (http://www-fars.nhtsa.gov), which is a database of vehicle, person, and event characteristics from all fatal crashes on public roads. Population (P), land area in square miles (A), and RUCC values were obtained from the Area Resource File (ARF). The ARF database (http://arf.hrsa.gov/) contains geographic, demographic, and health resources data on each US county, compiled by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA).

RUCC are a classification that distinguishes metropolitan (metro) counties by the population size of their metro area, and nonmetropolitan (non-metro) counties by degree of urbanization and adjacency to another metro area. These codes are subdivided into nine groups, allowing researchers a measure of the rural-urban continuum for county data, and were developed by the Department of Agriculture's Economic Research Services (http://www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/Rurality/RuralUrbCon/). The most recent version of RUCC codes (from 2003) is shown in Table 1 -- values range from 1, indicating the most urban areas, up to 9, indicating the most rural areas.

Table 1.

2003 Rural-Urban Continuum Code (RUCC) definitions (http://arf.hrsa.gov).

| RUCC | Counties (N=3142) | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 414 | Counties in metro areas of 1 million population or more |

| 2 | 325 | Counties in metro areas of 250,000 to 1 million population |

| 3 | 351 | Counties in metro areas of fewer than 250,000 population |

| 4 | 218 | Urban population of 20,000 or more, adjacent to a metro area |

| 5 | 105 | Urban population of 20,000 or more, not adjacent to a metro area |

| 6 | 609 | Urban population of 2,500 to 19,999, adjacent to a metro area |

| 7 | 450 | Urban population of 2,500 to 19,999, not adjacent to a metro area |

| 8 | 235 | Completely rural or less than 2,500 urban population, adjacent to a metro area |

| 9 | 435 | Completely rural or less than 2,500 urban population, not adjacent to a metro area |

County-level VMT data were obtained from the National Mobile Inventory Model (NMIM) County Database (http://www.epa.gov/otaq/nmim.htm), managed by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). NMIM produces county-level vehicle emissions estimates, using state-level VMT data reported by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). NMIM applies a weighting algorithm to the state data based on miles of each of twelve road types in each county, resulting in an estimate of VMT for each county.

Analysis

Once the available data had been obtained and merged, we used the general methodology proposed by Li and Baker[14] to “decompose” the population-based mortality rate from crashes. We extended their original model to consider MVC data:

In order to evaluate this process of “decomposition”, it may be useful to explain this model in terms of conditionally independent probabilities. Explicitly, the probability of traffic death (D) for a given 1,000 members of some population (P) is equal to the probability of death given a traffic injury (I), times the probability of injury given a traffic crash (C), times the probability of a crash given a measure (million VMT) of exposure (E), times the probability that those 1,000 persons experience the specified number of VMT. We can express this symbolically as

| (Equation 1) |

In order to produce more symmetrical distributions, we can take the logarithm of both sides of the Equation 1 and produce the equivalent expression

| (Equation 2) |

In order to estimate the effect of some other factor among our units of observation (e.g., rural versus urban counties), we can modify the conditional probabilities from Equation 2 to include the marginal probabilities where a measure of “rurality” is included (R), that is,

| (Equation 3) |

For each measure of rurality in this study, each of the marginal probabilities above was estimated using linear regression:

| (Equation 4a) |

| (Equation 4b) |

| (Equation 4c) |

| (Equation 4d) |

| (Equation 4e) |

From Equation 3 and Equations 4a–4e,

The proportion of the rural effect on the left-hand relationship (traffic deaths per population) contributed by the rural effect on each of the right-hand factors, e.g. b1/b0, may then be used as a measure of the relative importance of each factor in producing the combined effect.

To measure rurality, we calculated population density (P/A) for each county. We also used the ordinal RUCC category for each county, and then created a binary indicator variable (1 if ”rural”, 0 otherwise) of rurality, by defining rural as RUCC of 4–9, and urban as RUCC of 1–3.

The model (Equation 3) was further extended by introducing a binary variable to indicate the southern states. We defined “southern” as a state mostly south of the 37th North Latitude, namely AL, AR, AZ, FL, GA, LA, MS, NM, NC, NV, OK, SC, TN, or TX. Terms c0…c4 were added to Equations 4a–4e to estimate the southern effect (S) and the relative contributions of the different components of P(D|P,R,S), that is the mortality rate from traffic crashes given both a measure of rural/urban area and southern/northern location.

As an alternative approach to comparing the relative importance of each right-hand factor on the left-hand effect in Equation 3, we constructed linear regression equations with one factor at a time, or leaving out one factor at a time, to demonstrate the proportion of the overall effect contributed by that factor. In either case, the adjusted coefficient of determination (r2) was compared to the r2 obtained when all the factors are included. This approach could be described as “decomposing” the sum of squared deviations from the model.

RESULTS

Out of the 3,142 counties in the United States, data for all six variables in the year 2007 were obtained for 1,754 counties (55.8%). No county data were available from seven southern states (GA, MS, NM, NV, OK, SC, NT) and nineteen other states (CO, CT, DE, HI, ID, IN, MA, ME, MO, ND, NH, NJ, NY, OR, PA, RI, VT, WV, WY). We report results only for the 2007 data, although the 1999 data produced similar results and are provided in an online appendix. Table 2 provides general characteristics of the county data collected for the year 2007. The number of MVC fatalities, injuries and total crashes varied widely by county. The average number of MVC fatalities per county in 2007 was 14, and ranged from 0 to 765. The average number of non-fatal injuries per county in 2007 was 943, and ranged from 0 to 82,480.

Table 2.

General characteristics of 2007 county data assembled for analysis.

| Factor | Source | N (counties with data) | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | ARF | 3,142 | 25,367 | 55 – 9,878,554 |

| Land area (mi2) | ARF | 3,142 | 617 | 2 – 145,900 |

|

| ||||

| MVC fatalities | FARS | 3,054 | 7 | 0 – 765 |

| MVC non-fatal injuries | State websites | 1,914 | 197 | 0 – 82,480 |

| Total MVC | State websites | 2,495 | 493 | 1 – 206,884 |

| VMT (in millions) | NMIM (EPA) | 3,138 | 321 | 2 – 85,463 |

MVC – Motor vehicle crash; FARS – Fatality Analysis Reporting System; ARF – Area Resource File; VMT – Vehicle miles traveled; NMIM – National Mobile Inventory Model; EPA – Environmental Protection Agency

The 1,754 counties for which complete data were available were 64.4% rural (RUCC 4–9), compared with 65.3% for all US counties. After excluding Alaska and Hawaii, 1151 of the remaining counties (37.0%) were classified as southern, whereas 606 (34.7%) of the counties with complete data were southern.

Logarithmic transformation of the population-based mortality (D/P) by county produced a generally symmetrical distribution, and graphical analysis of residuals after fitting models predicting Log[D/P] using different measures of rurality produced symmetrical distributions with a random pattern to the prediction errors.

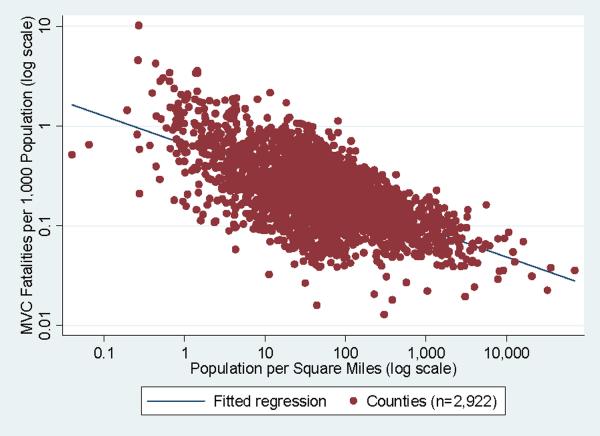

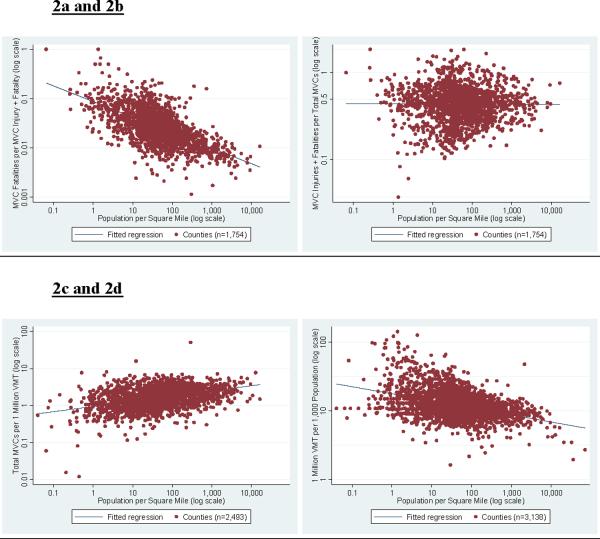

Figure 1 shows the inverse relationship (decreasing population, increasing death rate) between the logarithms of population density (X=Log[P/A]) and population MVC death rate (Y=Log[D/P]) which has been noted in previous studies.[1, 6] Figure 2(a.–d.) shows that the relationship to X=Log(P/A) is similarly negative in 2a: Y=Log(D/I), relatively constant in 2b: Y= Log(I/C), slightly positive in 2c: Y= Log (C/E), and slightly negative in 2d: Y= Log(E/P).

Figure 1.

Scatterplot of 2007 county data for the logarithm of overall county traffic deaths per population (D/P), plotted against the logarithm of population density (P/A).

Figure 2a–d.

Scatterplots of 2007 county data for the logarithms of the four ratios (D/I, I/C, C/E, E/P) in the decomposition formula, plotted against the logarithm of population density.

Model results from the linear regressions are displayed in Table 3, for each of three different measures of rurality on the logarithm of each ratio. The first column corresponds to the relationships depicted in Figures 1–2, using population density as a measure of rurality. The second column shows the β-coefficients from linear regressions of the RUCC classification of rurality, and the third column shows the β-coefficients from a simple regression of an indicator variable where urban is 0 and rural is 1. The strongest magnitude appears to be in Log(D/I) for any of the measures of rurality, compared to the relationships of Log(I/C), Log(C/E), or Log(E/P) to rurality. We interpret this to mean that the increased rate of traffic deaths in the rural population is most influenced by the increased probability of death given that a traffic injury has occurred in a rural area.

Table 3.

β-coefficients (±standard error) from univariate linear regressions using three different measures of rurality: Logarithm of population density, RUCC, and a binary rural/urban variable. The log-transformed ratios from our decomposition formula are the dependent variables and the measures of rurality are the independent variables in each regression.

| Dependent variables (Log-transformed) | N | Rural effect βr (±SE) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rurality = Log[P/A] | |||

| Deaths/Population (D/P) | 2925 | −0.282 (0.007)* | 0.38 |

| Deaths/Injuries (D/I) | 1757 | −0.315 (0.009)* | 0.40 |

| Injuries/Crashes (I/C) | 1878 | 0.004 (0.006) | 0.00 |

| Crashes/Exposure (C/E) | 2493 | 0.140 (0.006)* | 0.16 |

| Exposure/Population (E/P) | 3138 | −0.103 (0.004)* | 0.18 |

| Rurality = RUCC | |||

| Deaths/Population (D/P) | 2926 | 0.057 (0.002)* | 0.21 |

| Deaths/Injuries (D/I) | 1757 | 0.063 (0.003)* | 0.23 |

| Injuries/Crashes (I/C) | 1878 | −0.006 (0.002) | 0.01 |

| Crashes/Exposure (C/E) | 2493 | −0.024 (0.002)* | 0.06 |

| Exposure/Population (E/P) | 3138 | 0.019 (0.001)* | 0.07 |

| Rurality = 1 vs. 0 | |||

| Deaths/Population (D/P) | 2926 | 0.246 (0.012)* | 0.13 |

| Deaths/Injuries (D/I) | 1757 | 0.271 (0.016)* | 0.13 |

| Injuries/Crashes (I/C) | 1878 | −0.028 (0.010)* | 0.01 |

| Crashes/Exposure (C/E) | 2493 | −0.098(0.011)* | 0.03 |

| Exposure/Population (E/P) | 3138 | 0.076 (0.007)* | 0.04 |

p<.05

KEY: Deaths = MVC fatalities; Population = 1,000 persons; Injuries = MVC injuries including fatalities; Crashes = total MVCs; Exposure = million vehicle miles traveled; Population Density = population per square mile; RUCC = Rural-Urban Continuum Code; N = Observations in model; R2 = Coefficient of determination

The coefficient of determination (r2) for several linear regressions of Log(D/P) against the logarithms of the component ratios provided confirmation of the relative importance of the components. When all four rates from the decomposition are included as independent variables, r2 necessarily equals 1. The individual rate contributing most to the overall rate of deaths per population was the logarithm of deaths per injury. Alone, Log(D/I) accounted for 62% (r2=0.622) of the sum of the squared residuals in the regression; when only this term was excluded from the regression, r2=0.220. The logarithm of exposure per population was the next most influential variable. Alone, Log(E/P) accounted for 20% (r2=0.200) of the sum of the squared residuals in the regression; when only this term was excluded from the regression, r2=0.810.

Table 4 shows the results of linear regressions of the three measures of rurality, controlling for the southern versus northern effect, against the logarithms of each ratio. In this analysis, the effect of rurality on each ratio is similar to the result in the corresponding univariate regression. The β-coefficients from the regression for Log(D/P) show that there is an increased rate of traffic deaths per population in southern states. The strongest effect of southern (controlling for rurality) for the four ratios is with Log(I/C). That is, the increased southern rate of traffic deaths per population (after controlling for rural location) is most influenced by the increased probability of injury given that a traffic crash has occurred in one of the southern states.

Table 4.

β-coefficients (±standard error) from linear regressions using three different measures of rurality: Logarithm of population density, RUCC, and a binary rural/urban variable. The log-transformed ratios from our decomposition formula are the dependent variables and the measures of rurality and southern location are the independent variables in each regression.

| Dependent variables (Log-transformed) | N | Rural effect βr (±SE) | Southern effect βs (±SE) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rurality = Log[P/A] | ||||

| Deaths/Population (D/P) | 2907 | −0.288 (0.007)* | 0.142 (0.010)* | 0.43 |

| Deaths/Injuries (D/I) | 1749 | −0.314 (0.009)* | −0.033 (0.014)* | 0.40 |

| Injuries/Crashes (I/C) | 1863 | 0.004 (0.006) | 0.217 (0.009)* | 0.25 |

| Crashes/Exposure (C/E) | 2466 | 0.128 (0.006)* | −0.073 (0.010)* | 0.15 |

| Exposure/Population (E/P) | 3106 | −0.112 (0.004)* | 0.049 (0.006)* | 0.21 |

| Rurality = RUCC | ||||

| Deaths/Population (D/P) | 2908 | 0.058 (0.002)* | 0.153 (0.011)* | 0.26 |

| Deaths/Injuries (D/I) | 1749 | 0.063 (0.003)* | −0.009 (0.016) | 0.22 |

| Injuries/Crashes (I/C) | 1863 | −0.002 (0.002) | 0.215 (0.009)* | 0.25 |

| Crashes/Exposure (C/E) | 2466 | −0.023 (0.002)* | −0.080 (0.011)* | 0.08 |

| Exposure/Population (E/P) | 3106 | 0.019 (0.001)* | 0.052 (0.007) | 0.09 |

| Rurality = 1 vs. 0 | ||||

| Deaths/Population (D/P) | 2908 | 0.247 (0.012)* | 0.144 (0.012)* | 0.17 |

| Deaths/Injuries (D/I) | 1749 | 0.268 (0.016)* | −0.027 (0.016) | 0.14 |

| Injuries/Crashes (I/C) | 1863 | −0.018 (0.009)* | 0.216 (0.009)* | 0.25 |

| Crashes/Exposure (C/E) | 2466 | −0.091 (0.011)* | −0.074 (0.011)* | 0.05 |

| Exposure/Population (E/P) | 3106 | 0.078 (0.007)* | 0.048 (0.007)* | 0.05 |

p<.05

KEY: Southern state defined as lying mostly below 37° North latitude (AL, AR, AZ, FL, GA, LA, MS, NM, NC, NV, OK, SC, TN, TX); Pop. Dens = population per square mile; Deaths = MVC fatalities; Population = 1,000 persons; Injuries = MVC injuries including fatalities; Crashes = total MVCs; Exposure = million vehicle miles traveled; RUCC = Rural-Urban Continuum Code; N = Observations in model; R2 = Coefficient of determination

DISCUSSION

Our results show that of the four components in our decomposition formula, deaths per injury (D/I) has the strongest influence on the rural-urban difference in traffic deaths per population (D/P). The increased rates of deaths per injury (D/I) after vehicle crashes in rural areas has been recognized for many years.[2, 15] Beyond confirming the results of Zwerling and colleagues,[13] the strong dose-response effect from different measures of rurality in our study demonstrates that the rural effect on the mortality rate from MVC is not confined only to counties above a certain remote level, but is distributed across the rural-urban continuum.

Previous studies of the rural/urban difference in traffic mortality have noted that there is a further effect of residence in the southern part of the United States.[6, 7] Our analysis suggests that the “southern effect” is not due to differences in deaths per injury (D/I), but instead to an increased probability of injury when crashes occur (I/C), possibly from higher average speeds, less use of safety belts, more occupants per vehicle, or other factors. Further investigation of this regional disparity in injury rates is warranted.[7]

As Hemenway[16] has pointed out, there are many possible ways to decompose a rate or ratio. Similar ideas may also be expressed using other terms such as “disaggregation”[17], “disentangling”[18], or “partitioning”[19]. The method proposed by Li and Baker[14] might be distinguished as “sequential decomposition” or “conditional decomposition”, since it takes advantage of a situation where the explanatory factors constitute a sequence of conditional probabilities, which may be further conditioned upon additional factors.

The most frequent use of the term “decomposition” in the health care literature refers to analyzing an apparent rate ratio for some risk factor on two populations by separating the distribution of specified characteristics of the populations (e.g., standardization) from the estimated effect of the risk factor on specified subpopulations. Among demographers, decomposition of this sort is generally attributed to the initial ideas of Kitagawa[20] and DasGupta[21], while among economists it follows the formulations of Blinder[22] and Oaxaca[23]. The former approach has been used to study differences in population health,[24, 25, 26] and the latter to evaluate health services usage by insurance status[27] or rural/urban residence[28].

The purpose of any decomposition is to explain an overall rate in terms of multiple components, and further to explain how that rate may be affected by one or more other factors. If there are only two populations (e.g., rural versus urban), the equation we utilized reduces to

where RR is the risk ratio of the effect on each sequential component. This formula was used by Li and colleagues.[9]

Although our measurement of the relative effects of each component has some similarity to a calculation of population attributable fraction (PAF),[29] there are important differences. First, we are intentionally using counties as equally important units of observation regardless of their populations; second, we are comparing on a logarithmic scale, which will reduce the magnitude of the apparent differences; and third, we are assuming that there are no interactions between the rural effects on different conditional probabilities. Mason and Tu[30] have proposed a method for estimating the PAF when a sequence of probabilities is modeled, even if there are interactions. However, even if a PAF were calculated, there is considerable controversy about the best ways to interpret it, especially the admonition that attributable risk does not necessarily imply causation.[31]

Decomposition of traffic mortality into variables measuring exposure, crash risk, and crash severity has been employed by other traffic researchers in various forms. Smeed [32] appears to have been the first to consider this idea, decomposing the population-based traffic mortality (D/P) into deaths per vehicle (D/V) and vehicles per person (V/P) for several countries, and performing more limited analyses of other ratios. Zwerling and colleagues[13] disaggregated fatal crashes per VMT into three components using data from the National Automotive Sampling System - General Estimates System (NASS-GES), and dichotomously compared these rates on rural versus urban roads. Hermans and colleagues[33] have reported an interesting time-series analysis separating deaths per crash, crashes per vehicle, and number of vehicles, demonstrating which factors have most affected each of these components in Belgium over time.

Our small-area (county) analysis extends the approach of Li and Baker[14] in another direction. Because we have data from the majority of the U.S. counties for four components and the overall rate of traffic deaths per population, we were able to construct models that demonstrate “dose-response” curves for two measures of rurality (RUCC and population density). Our analysis of the rural-urban continuum strengthens the argument that some factor related to rurality is a direct cause of the increased rural rate of traffic deaths given a traffic injury, and thereby the increased overall rural rate of traffic deaths.

We have assumed that the rural-urban differences in D/I and D/P are at least partially due to geographic restrictions imposed by greater distances on the mobilization of emergency medical services and the transportation of seriously injured persons to hospitals and trauma centers. However, we recognize that the simple decomposition presented here does not account for possible differences in injury severity, or possible bias between rural and urban crashes in reporting injuries after MVC.

There are a number of other limitations to this study. Data on non-fatal injuries and total crashes, accumulated from multiple state websites, do not represent every US county, and omit several states completely, resulting in further possibilities for selection bias. Additionally, variables such as “non-fatal injury” may have been defined in different ways depending on the state. Vehicle miles traveled by county were not measured directly, but are estimates based on state level data and a county-weighting algorithm created by the EPA. Furthermore, VMT are not necessarily a consistent measure of exposure, since the risk may be different depending upon the driving conditions and other factors. Though these limitations in our data require caution in the interpretation of our results, we believe our large sample size (1,754 or more counties) make the data sufficiently reliable at least for this exploratory analysis.

The methodologic construct of decomposing the rate of deaths in the population into four components also has definite limitations. However, we only sought to make general observations about factors underlying the rural-urban and southern-northern disparities. Although traffic deaths are probably the most accurately measured variable in the data presented here, there may be less reliability in the measurement of non-fatal injuries, which could affect either D/I or I/C. Similarly, the measurement of exposure (VMT) might reflect the accumulation of highway miles by non-residents merely passing through a rural county, which could affect either C/E or E/P. Finally, the decomposition formula assumes that each conditional probability is independent of the others, whereas in actuality the effects are likely to overlap.

While county-level data are useful and easily understood, we are also well aware of the “ecologic fallacy”[34] and hesitate to pursue any further analysis based only on regionally aggregated data. Analysis of MVC mortality using a multilevel or hierarchical regression model combining person-level and/or event-level information with county-level and/or state-level information would appear to be a better way to proceed. This approach involves partitioning model variance between levels of analysis, essentially allowing for a more sophisticated type of “decomposition”.[35] While proceeding to apply these more detailed methods, we believe the simple regional analyses presented here and elsewhere may provide helpful guidance for the most productive areas of concentration.

KEY MESSAGES.

What is already known on this subject

-

--

The traffic crash mortality rate is greater in rural and southern areas of the US.

-

--

“Decomposing” the population-based rate into conditional probabilities may be a useful way to analyze such a disparity.

-

--

A previous study considering “rural” as a binary variable suggested that the rural disparity is principally due to the increased probability of death given an injury (D|I).

What this study adds

-

--

The methodology previously described for “decomposition” has been extended to include one or more continuous or ordinal variables.

-

--

When “rural” was defined as a continuous or ordinal variable, the rural disparity in D|I was still the most important determinant of the increased mortality rate.

-

--

The most important component of the southern disparity was not D|I but the increased probability of injury given a crash (I|C).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funded in part by US National Institutes of Health Award R21HD061318.

Footnotes

LICENSE AGREEMENT

“The [Corresponding Author] has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in IP and any other BMJPGL products to exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our licence.” http://injuryprevention.bmj.com/site/about/licence.pdf

COMPETING INTERESTS None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker SP, Whitfield RA, O'Neill B. Geographic variations in mortality from motor vehicle crashes. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1384–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198705283162206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brodsky H, Hakkert AS. Highway fatal accidents and accessibility of emergency medical services. Soc Sci Med. 1983;17:731–40. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maio RF, Green PE, Becker MP, et al. Rural motor vehicle crash mortality: the role of crash severity and medical resources. Accid Anal Prev. 1992;24:631–42. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(92)90015-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muelleman RL, Walker RA, Edney JA. Motor vehicle deaths: a rural epidemic. J Trauma. 1993;35:717–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esposito TJ, Sanddal ND, Hansen JD, et al. Analysis of preventable trauma deaths and inappropriate trauma care in a rural state. J Trauma. 1995;39:955–62. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199511000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark DE, Cushing BM. Predicting regional variations in mortality from motor vehicle crashes. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:125–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Washington S, Metarko J, Fomunung I, et al. An inter-regional comparison: fatal crashes in the southeastern and non-southeastern United States: preliminary findings. Accid Anal Prev. 1999;31:135–46. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(98)00055-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rating the severity of tissue damage. I. The abbreviated scale. JAMA. 1971;215:277–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.1971.03180150059012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li G, Baker SP, Langlois JA, et al. Are female drivers safer? An application of the decomposition method. Epidemiology. 1998;9:379–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dellinger AM, Langlois JA, Li G. Fatal Crashes among Older Drivers: Decomposition of Rates into Contributing Factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:234–41. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.3.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meuleners LB, Harding A, Lee AH, et al. Fragility and crash over-representation among older drivers in Western Australia. Accid Anal Prev. 2006;38:1006–10. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li G, Braver ER, Chen LH. Fragility versus excessive crash involvement as determinants of high death rates per vehicle-mile of travel among older drivers. Accid Anal Prev. 2003;35:227–35. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(01)00107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zwerling C, Peek-Asa C, Whitten PS, et al. Fatal motor vehicle crashes in rural and urban areas: decomposing rates into contributing factors. Inj Prev. 2005;11:24–8. doi: 10.1136/ip.2004.005959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li G, Baker SP. Exploring the male-female discrepancy in death rates from bicycling injury: the decomposition method. Accid Anal Prev. 1996;28:537–40. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(96)00015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark DE. Effect of population density on mortality after motor vehicle collisions. Accid Anal Prev. 2003;35:965–71. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(02)00104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hemenway D. The decomposition method. Epidemiology. 1998;9:369–70. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199807000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rennison CM, Planty M. Reassessing who contributed most to the decline in violence during the 1990s: a reminder that size does matter. Violence Vict. 2006;21:23–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldman N. Social inequalities in health disentangling the underlying mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;954:118–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Land M, Vogel C, Gefeller O. Partitioning methods for multifactorial risk attribution. Stat Methods Med Res. 2001;10:217–30. doi: 10.1177/096228020101000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitagawa E. Components of a difference between two rates. J Am Statist Assoc. 1955;50:1168–94. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das Gupta P. A general method of decomposing a difference between two rates into several components. Demography. 1978;15:99–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blinder AS. Wage discrimination: Reduced form and structural estimates. J Human Resources. 1973;8:436–55. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oaxaca RL. Male-female wage differentials in urban labor markets. Int Econ Review. 1973;14:693–709. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Rahman A, Siegal HA, et al. Standardization and decomposition of rates: useful analytic techniques for behavior and health studies. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2000;32:357–66. doi: 10.3758/bf03207806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nusselder WJ, Looman CW. Decomposition of differences in health expectancy by cause. Demography. 2004;41:315–34. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Q, Greenland S, Flanders WD. Associations of maternal age- and parity-related factors with trends in low-birthweight rates: United States, 1980 through 2000. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:856–61. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.049312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mortensen K, Song PH. Minding the gap: a decomposition of emergency department use by Medicaid enrollees and the uninsured. Med Care. 2008;46:1099–107. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318185c92d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vogel WB, Dwyer JW, Barton AJ. Decomposing area of residence differences in multiple regression studies: the relative contributions of independent variables and model coefficients. J Rural Health. 1994;10:258–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1994.tb00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kopjar B. Population preventable fraction of bicycle related head injuries. Inj Prev. 2000;6:235–8. doi: 10.1136/ip.6.3.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mason CA, Tu S. Partitioning the population attributable fraction for a sequential chain of effects. Epidemiol Perspect Innov. 2008;5:5. doi: 10.1186/1742-5573-5-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rockhill B, Newman B, Weinberg C. Use and misuse of population attributable fractions. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:15–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smeed RJ. Some statistical aspects of road safety research. J Royal Statist Soc A. 1949;112:1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hermans E, Wets G, Van den Bossche F. Describing the evolution in the number of highway deaths by decomposition in exposure, accident risk, and fatality risk. Transportation Research Record. 2006;1950:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piantadosi S, Byar DP, Green SB. The ecological fallacy. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;127:893–904. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel Analysis. Sage; London: 1999. [Google Scholar]