Abstract

Introduction

Extensive observational data suggest that HSV-2 infection may facilitate HIV acquisition, increase HIV viral load, and accelerate HIV progression and onward transmission. To explore these relationships, we examined the impact of pre-existing HSV-2 infection in an international HIV vaccine trial.

Methods

We analyzed the associations between prevalent HSV-2 infection and HIV-1 acquisition and progression among 1836 men who have sex with men (MSM). We used Cox proportional hazards regression models to estimate the association between HSV-2 infection and both HIV acquisition and ART initiation, and linear regression to explore the effect of HSV-2 on pre-ART viral load.

Results

HSV-2 infection increased risk of HIV-1 acquisition among all volunteers (adjusted hazard ratio 2.2; 95% CI, 1.4 to 3.5). Adjusting for demographic variables, circumcision, Ad5 titer and significant risk behaviors, the risk of HIV acquisition among HSV-2 infected placebo recipients was three fold higher than HSV-2 seronegatives (hazard ratio 3.3; 95% CI, 1.6 to 6.9). Past HSV-2 infection was associated with a 0.2 log10 copies/ml higher adjusted mean set point viral load (95% CI, 0.3 lower to 0.6 higher). HSV-2 infection was not associated with time to ART initiation.

Conclusions

Among MSM in an HIV-1 vaccine trial, pre-existing HSV-2 infection was a major risk factor for HIV acquisition. Past HSV-2 did not significantly increase HIV viral load or early disease progression. HSV-2 seropositive persons will likely prove more difficult than HSV-2 seronegative persons to protect against HIV infection using vaccines or other prevention strategies.

Keywords: Herpes Simplex Virus Type II, HIV incidence

Introduction

Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) is a common, persistent sexually transmitted infection (STI) and the leading cause of genital ulcer disease (GUD).1, 2 One in six adults worldwide are infected,1 with seroprevalence estimates ranging from 17% of adult Americans3 to as many as 30%–80% of women in sub-Saharan Africa2, and 40% of HIV-negative and 80% of HIV-positive men who have sex with men (MSM) in Latin America.4 The major burden of HSV-2 infection lies in frequent, recurrences - at least 80% of which are asymptomatic or present with atypical symptoms.5 Emerging data suggest that short bursts of subclinical viral shedding occur frequently, with higher levels of shedding as detected by DNA PCR on about 20% of days.6–9 These frequent shedding episodes facilitate HSV-2 transmission and may increase susceptibility to HIV infection in HSV-infected people by activating HIV target cells in the genital tract.10–13

The interactions between HIV and HSV-2 exemplify the epidemiologic synergy that creates a mutually reinforcing spiral of infection between HIV and other STIs.14 Numerous observational studies from four continents suggest a 2–3 fold increased risk of HIV acquisition associated with prevalent HSV-2 infection and an up to 7-fold increased risk with incident HSV-2 infection.15, 16 Conversely, HIV-1 infection increases acquisition of HSV-2 approximately 3–5-fold. 11, 17 Moreover, HIV-1/HSV-2 co-infected individuals may exhibit a 0.30–0.55 log10 copies/ml higher HIV viral load than those without HSV-2 co-infection, 18–21 which may translate to more rapid progression to AIDS and/or increased HIV infectiousness for sexual partners.22–24 Despite this synergy, two randomized controlled trials of suppressive HSV-2 therapy to prevent HIV acquisition and one to prevent transmission have not demonstrated a significant effect of HSV-2 therapy to reduce HIV acquisition.25–27 This may relate to the ineffectiveness of current antiviral regimens in preventing viral reactivation from sacral nerve root ganglia and the resultant persistence of HIV receptor positive cells in the genital mucosa even with prolonged acyclovir therapy.28

The Step Study was a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled test-of-concept trial to assess the efficacy of a cell-mediated HIV-1 adenovirus 5 vectored vaccine (MRKAd5).29 A key question that emerged from the trial was whether HSV-2 infection modified vaccine effect on acquisition, particularly among uncircumcised men who had preexisting immunity to the Ad5 vector. The Step Study also provided a unique opportunity to analyze the role of HSV-2 infection in HIV acquisition and disease progression and as a potential modifier of vaccine effect among MSM in the Americas and Australia. Therefore, we explored the epidemiology of HSV-2 infection and evaluated its impact on HIV incidence, viral load and time to ART initiation among Step Study participants.

Methods

Study design and population

We analyzed HSV-2 associations in the Step Study cohort, which has been described previously.29 Briefly, from December 2004, 3000 HIV-1 negative 18 to 45 year old volunteers at high risk for HIV-1 infection from 34 sites in the Americas, the Caribbean and Australia were randomized to receive either 3 doses of the MRKAd5 HIV-1 vaccine or placebo. Randomization was stratified by site, gender and baseline Ad5 titer. Volunteers had clinical evaluations and risk reduction counseling at each visit (day 1, weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 26, 30, 52, and every 26 weeks thereafter) with HIV-1 testing on day 1, week 12 and all subsequent visits (except week 26). Baseline HSV-2 testing was performed on day 1 or weeks 2 or 4 samples. Self-reported sexual risk behaviors, drug use and STIs were evaluated at screening and every 26 weeks thereafter using standardized interviewer-administered questionnaires. Vaccinations in the study were stopped early, in September 2007, and study volunteers were subsequently unblinded to their treatment assignment when pre-specified non-efficacy criteria were met at the first interim analysis. Analysis of the 1,836 male Step trial participants demonstrated that the vaccine did not prevent HIV acquisition or reduce early viral load.29 Exploratory analyses showed a trend towards higher HIV incidence in subgroups of the vaccinees: HIV incidence was higher among men with pre-existing immunity to Ad5 (hazard ratio comparing vaccine and placebo 2.3; 95% CI, 1.2 to 4.3) and among uncircumcised men (hazard ratio comparing vaccine and placebo, 3.8; 95% CI, 1.5 to 9.3) at 18 months – this trend waned over time 30. The current analysis also focuses on these 1,836 high risk men (there was one infection among women), of whom >96% reported sex with men. Of the 1,836 men, 922 received placebo and 914 received vaccine. Eighty-eight of the men (36 placebo and 52 vaccine recipients) acquired HIV prior to October 17 2007, after which trial volunteers were unblinded to the intervention. At the time of unblinding, the majority, 1704/1836 or 93% of male volunteers received all three vaccinations, 96 (5%) received two, and 36 (2%) received one vaccination. One volunteer initiated anti-retroviral therapy (ART) prior to HIV seroconversion and is excluded from the time to ART initiation and viral load analyses. Twenty eight (12 placebo and 16 vaccine recipients) of the remaining 87 men initiated ART by March 23, 2009. The protocol did not specify criteria for ART initiation. Primary care physicians initiated ART according to clinical judgment and local guidelines, with some clinicians treating acute HIV infection. Other clinicians followed ART guidelines from the United States Department of Health and Human Services31, the World Health Organization32 or the International AIDS Society-USA33.

Volunteers underwent a thorough written informed consent process. The study protocol was approved by the ethics review committee of each site and was conducted according to relevant local and national requirements. The Step Study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00095576.

Laboratory methods

Baseline HSV-2 was diagnosed by Western blot (WB) at the University of Washington Diagnostic Virology Laboratory. A gold standard HSV assay since the mid 1980s, WB can identify subtype-specific antibodies (HSV-1 only, HSV-2 only, and HSV-1 and HSV-2) in 95 to 98% of samples.34 We excluded from analysis 10 (0.3%) samples with an undetermined result that could not be resolved by a retest on a subsequent specimen collected less than 8 weeks after the first vaccination.

HIV was diagnosed by immunoassay, with WB and RNA (Amplicor Monitor version 1.5, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) assay confirmation on the original and confirmatory specimens.29 If HIV was diagnosed at any visit, stored plasma was tested from earlier time points to accurately time the onset of HIV-1 infection. All cases were unanimously confirmed by a blinded endpoint adjudication committee. Ad5 titers were measured by a dilution assay based on serum inhibition of adenovirus infection.

Statistical analysis

Both direction stepwise procedures were used to select risk behavior variables that contributed to improved model fitting in terms of the exact Akaike’s Information Criteria (AIC) 35 in the analysis of HSV-2 sero-positivity and HIV acquisition. Observations with missing information on HSV-2 (10 out of 1836) and other covariates were excluded in the model selection procedure and in the final reported models. A two-sided p-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

In the analysis of HSV-2 data, we used logistic regression models to assess the association of baseline HSV-2 sero-positivity with baseline demographic, clinical and behavioral factors. These factors included age (<=30 or >30), region (North America and Australia or Latin America and the Caribbean), race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, Mestizo, multi-racial or other), Ad5 titer (<=18 or >18), self-reported male circumcision (yes or no), and risk behaviors such as drug use (yes or no), number of sex partners in the last six months (<=4 or >4), unprotected receptive/insertive anal intercourse with partners of unknown, seropositive and seronegative HIV infection status (yes or no). Data were analyzed using Stata/SE 10.0.36

In the analysis of HIV acquisition data, the time-to-event variable in the survival analysis was defined as time from first vaccination to the midpoint between the date of the last visit with no evidence of HIV infection (HIV seronegative and HIV-1 plasma viral RNA negative) and the date of the first serologic evidence of HIV-1 infection. For subjects who never showed any evidence of HIV-1 infection before this dataset was closed, their time-to-event variable was right censored on October 17, 2007. We used Kaplan Meier curves and log-rank tests to display and assess the effect of HSV-2 univariately on the rate of HIV acquisition among placebo recipients, and among all trial participants.

We used Cox proportional hazards regression models to estimate the association of baseline HSV-2 seropositivity with HIV acquisition and ART initiation, with and without adjustment of the aforementioned baseline covariates in addition to intervention assignment (vaccine or placebo) and the interaction between intervention and male circumcision, when appropriate. In addition to the baseline risk behaviors, we explored the impact of risk behaviors within 6 months prior to HIV infection. Proportional hazard assumptions were assessed with the method described by Grambsch and Therneau.37

In the analysis of ART initiation, the time-to-event variable was defined as the time between HIV- 1 diagnosis and initiation of ART. Subjects who did not initiate therapy were censored at their last contact as of March, 2009. We used Kaplan Meier curves to display the effect of HSV-2 univariately on the rate of ART initiation among all HIV seroconverters.

Analyses of pre-ART viral load focused on viral load “set point”, which was the numeric average of week 8 and 12 post-infection values. Missing observations were imputed based on previous viral load and CD4 measures, treatment assignment, HSV-2 status at baseline and Ad5 seropositivity at baseline.38, 39 Associations between viral load set point and HSV-2 status were assessed using linear regression models, where inference accounted for the uncertainty in the imputed viral load values. Covariates plausibly associated with viral load, or shown to be associated with acquisition in the Step study, were included as covariates in the models for ART initiation and viral load.

Results

Risk factors for HSV-2 infection

Baseline prevalence of HSV-2 antibodies among the 1,836 volunteers was 30%. Most (418) HSV-2 infected individuals were both HSV-1 and HSV-2 seropositive, while 128 were HSV-2 positive only. In univariate analysis, HSV-2 prevalence was balanced between placebo and vaccine male recipients (31% and 29%, respectively). Regional variation was striking, with HSV-2 prevalence of 42% in Latin America and the Caribbean and 23% in North America and Australia. All of the 19 baseline factors that were examined exhibited a significant association with HSV-2 sero-positivity, except self reported STD and GUD which were rare in the cohort (Appendix Table 1). In multivariate analysis, HSV-2 infection at baseline was significantly more common among volunteers who were older (≥30 years), black, Hispanic, Mestizo or multi-racial (borderline significant), reported having more than 4 male partners, or reported unprotected insertive or receptive anal sex during the 6 months prior to vaccination (Table 1). Circumcision was associated with a borderline significant reduction (p value = 0.07) in HSV-2 infection among MSM in the Step Study (odds ratio 0.7; 95% CI, 0.5 to 1.0); the association was stronger (p = 0.003; odds ratio 0.63; 95% CI, 0.47 to 0.85) when region was not included in the multivariate model due to the high correlation between circumcision status and region in the study population.

Table 1.

Multivariate analysis of risk factors for HSV-2 seropositivity at baseline

| Baseline risk factor | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Male circumcision (circumcised) | 0.7 (0.5–1.0) | 0.070 |

| Race or ethnicity group | ||

| White | 1.0 | |

| Black | 2.0 (1.3–2.9) | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 1.7 (1.1–2.5) | 0.012 |

| Mestizo/Mestiza | 2.5 (1.6–4.0) | <0.001 |

| Multi-racial | 2.0 (1.0–3.9) | 0.052 |

| Other | 1.1 (0.6–2.2) | 0.718 |

| North America and Australia region | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 0.095 |

| Age younger than 30 years | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | <0.001 |

| Ad5 titer greater than 18 | 1.1 (0.9–1.5) | 0.233 |

| Risk behaviors (6 months prior to enrollment) | ||

| Number of male partners (>4) | 1.6 (1.2–2.1) | 0.001 |

| Unprotected insertive anal sex | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.038 |

| Unprotected receptive anal sex | 1.5 (1.1–2.0) | 0.005 |

Covariates were added sequentially and included in the multivariate analysis if they were selected in the stepwise model selection procedure, with HSV-2 seropositivity as the outcome of interest.

Effect of HSV-2 infection on HIV acquisition

Among the 88 men who acquired HIV prior to October 17, 2007, there were 33 HSV-2 seronegative vaccinees, 18 HSV-2 seronegative placebos, 19 HSV seropositive vaccines and 17 sero-positive placebos. For the cohort of 1,836 male volunteers, the median follow-up time before infection was 384 (range: 0 to 939) days overall, 386 (0 to 920) days for HSV-2 sero-negative vaccinees, 397 (0 to 915) days for HSV-2 sero-negative placebos, 379 (0 to 939) days for HSV-2 sero-positive vaccinees and 369 (0 to 919) days for HSV-2 sero-positive placebos.

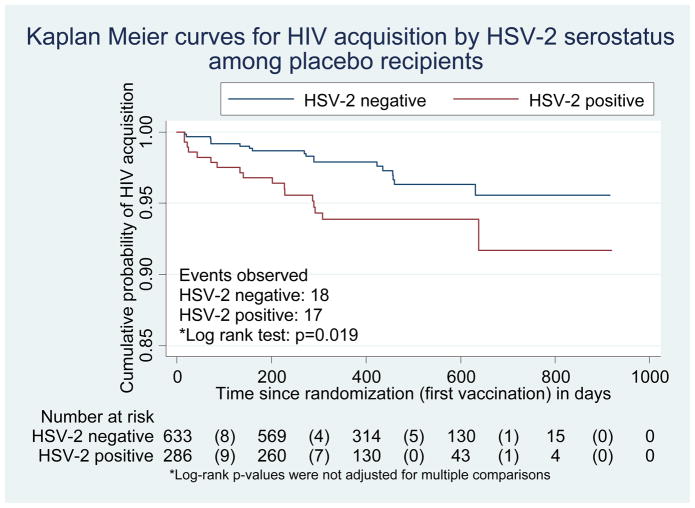

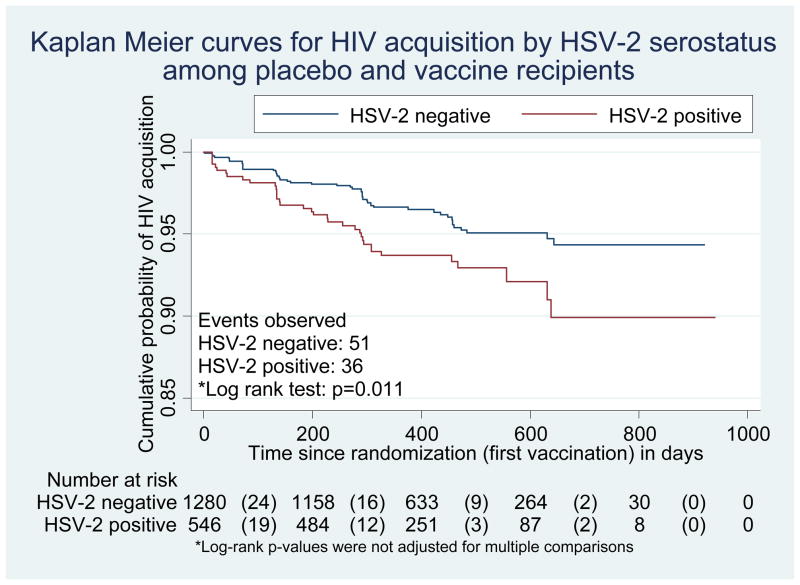

Pre-existing HSV-2 antibodies were associated with increased HIV-1 acquisition both among placebo recipients (log-rank p=0.019; Figure 1a) and among all trial participants (p=0.009; Figure 1b). Among placebo recipients, in the univariate Cox model, the hazard ratio of HIV acquisition for HSV-2 seropositive compared with HSV-2 seronegative volunteers was 2.2 (95% CI, 1.1 to 4.2). In multivariate Cox models, no significant interactions were found between HSV-2 infection and preexisting Ad5 immunity or circumcision. Adjusting for demographic variables, circumcision status, Ad5 titer and significant risk behaviors, the risk of HIV acquisition among placebo recipients with baseline HSV-2 infection was more than three times that observed among those without HSV-2 infection (hazard ratio 3.3; 95% CI, 1.6 to 6.9; Table 2a). Recent risk behaviors (in the 6 months prior to infection or the last visit) did not change the association between HSV-2 and HIV acquisition and were not included in the final model.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Kaplan Meier plot for HIV acquisition by baseline HSV-2 status among the placebo recipients

Numbers in parentheses represent number of HIV infections

Figure 1b. Kaplan Meier plot for HIV acquisition by baseline HSV-2 status among placebo and vaccine recipients

Numbers in parentheses represent number of HIV infections

Table 2a.

Multivariate analysis of risk factors for HIV acquisition among placebo recipients

| Baseline risk factors (6 months prior to enrollment)* | HR | 95% HR CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSV-2 (seropositive) | 3.3 | 1.6–6.9 | 0.001 |

| Age (<30 years) | 2.7 | 0.5–2.0 | 0.008 |

| Region (N. America & Australia) | 2.9 | 0.7–12.9 | 0.160 |

| Male circumcision (circumcised) | 2.5 | 0.7–8.7 | 0.150 |

| Ad5 titer (>18) | 1.0 | 0.5–2.0 | 0.920 |

| Unprotected insertive anal sex | 1.8 | 0.8–3.9 | 0.150 |

| Unprotected receptive anal sex | 2.1 | 1.0–4.6 | 0.060 |

In the model selection process, recent risk behaviors (measured in the 6 months prior to infection or last visit) did not change the model results and were not included in the final model.

When both placebo and vaccine recipients were considered in the univariate Cox model, HSV-2 infection had a similar impact on HIV acquisition (unadjusted hazard ratio 1.7; 95% CI, 1.1 to 2.7). No significant interactions between HSV-2 infection and Ad5 immunity, circumcision or exposure to the vaccine were observed, however, consistent with previously reported findings,29 a significant interaction was detected between circumcision and receipt of vaccine (p=0.013). After adjusting for all of these variables, the circumcision-vaccine interaction and risk behaviors selected from the stepwise model selection procedure, HSV-2 remained associated with an increased risk of HIV acquisition (adjusted hazard ratio 2.2; 95% CI, 1.4 to 3.5; Table 2b). In addition, young age (<30 years), location in North America or Australia, reporting unprotected insertive or receptive anal sex 6 months prior to vaccination (at baseline), speed use within 6 months prior to infection or last visit, and receiving vaccine if uncircumcised were independent predictors of HIV sero-conversion. Among recent risk behaviors, only speed use in the 6 months prior to infection or the last visit was significantly associated with HIV acquisition. However this risk behavior did not change the association between prevalent HSV-2 infection and HIV acquisition. In analyses of HIV acquisition among vaccinees compared with placebo recipients stratified by circumcision status and Ad5 sero-positivity, adjustment for baseline HSV-2 infection did not alter the risk of HIV acquisition associated with the vaccine.

Table 2b.

Multivariate analysis of risk factors for HIV acquisition among vaccine and placebo recipients

| Baseline risk factors (6 months prior to enrollment) | HR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSV-2 (seropositive) | 2.2 | 1.4–3.5 | <0.001 |

| Intervention (Vaccine)* | 0.003 | ||

| Vaccine HR among uncircumcised | 4.0 | 1.6–9.7 | |

| Vaccine HR among circumcised | 1.0 | 0.6–1.8 | |

| Male circumcision (circumcised)* | 0.140 | ||

| Circ HR among placebo recipients | 2.1 | 0.8–5.4 | |

| Circ HR among vaccinees | 0.5 | 0.3–1.1 | |

| Region (N. America & Australia) | 3.8 | 1.8–8.3 | <0.001 |

| Age (<30 years) | 2.2 | 1.3–3.5 | 0.002 |

| Ad5 titer (>18) | 1.2 | 0.8–2.0 | 0.380 |

| Unprotected insertive anal sex | 1.9 | 1.2–3.1 | 0.008 |

| Unprotected receptive anal sex | 1.8 | 1.1–3.0 | 0.016 |

| Recent risk behaviors (6 months prior to infection or last visit) | |||

| Speed use | 3.2 | 1.8–5.8 | <0.001 |

| Unprotected insertive anal sex with HIV negative partners | 0.6 | 0.3–1.0 | 0.064 |

|

| |||

| Unprotected receptive anal sex with HIV unknown partners | 1.6 | 0.9–2.6 | 0.100 |

The vaccine*circumcision interaction was significant (p=0.013)

Effect of HSV-2 infection on HIV viral load and time to ART initiation

Viral load set point was not significantly different between HSV-2 seropositive and HSV-2 seronegative HIV-1 seroconverters. Viral load measurements were missing at either week 8 or 12 for 47% of cases and were imputed. Of those missing values, 59% were due to missed visits, 17% to ART initiation, and 24% to study dropout. Using univariate linear regression models, mean set point viral load was 0.3 log10 copies/ml higher among HSV-2 seropositives than seronegatives (95% CI, 0.1 lower to 0.7 higher, Figure S1). Adjusting for study arm, region, circumcision status, age, race/ethnicity, Ad5 immunity, and HLA group reduced the effect (0.2 log10 copies/ml higher mean set point in HSV-2 seropositives; 95% CI, 0.3 lower to 0.6 higher). No significant interaction was identified between HSV-2 serostatus and vaccine exposure (p = 0.17). No difference in viral load trajectory was observed by HSV-2 serostatus in the placebo or vaccine groups (data not shown).

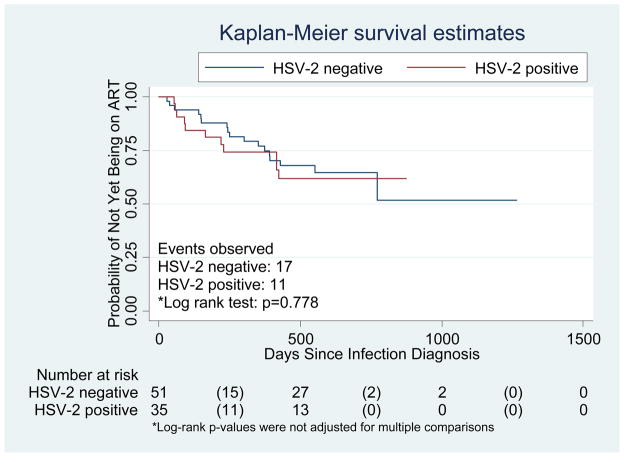

Of the 87 men studied in the post-infection analyses, 28 initiated ART (11 of 33 HSV2 negative vaccinees, 6 of 18 HSV2 negative placebos, 5 of 19 HSV2 positive vaccinees, and 6 of 16 HSV2 positive placebos). The median number of days between HIV diagnosis and ART initiation or censoring was 249 (range: 27 to 770) for HSV2 negative vaccinees; 315 (36 to 550) for HSV2 negative placebos; 61 (52 to 228) for HSV2 positive vaccinees; 289 (89 to 422) for HSV2 positive placebos. Of the 28 men who initiated ART, 24 were in the United States, 3 in Canada and 1 in Peru.

Pre-existing HSV-2 infection did not significantly alter time to ART initiation among HIV-1 infected participants by Kaplan Meier analysis in either arm of the trial (Figure 2). Similarly, using a Cox regression model, among all trial participants, HSV-2 infected volunteers were not significantly more likely than those who were HSV-2 uninfected to initiate ART (hazard ratio adjusted for Ad5 immunity, region, circumcision status, age, race, HLA group and treatment assignment 1.3; 95% CI, 0.5 to 3.2). There was no significant interaction between HSV-2 status and vaccine exposure (p = 0.47).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier plot for time to ART initiation by baseline HSV-2 serostatus among vaccine and placebo HIV seroconverters.

Numbers in parentheses represent number initiating ART

Discussion

We found that pre-existing HSV-2 infection was a frequent and important risk factor for HIV acquisition among MSM participating in a randomized controlled trial of the MRKAd5 HIV-1 vaccine from 34 sites in the Americas and Australia but did not significantly increase HIV viral load or early HIV disease progression (as measured by ART initiation) among seroconverters. Furthermore, HSV-2 infection did not alter the effect of the vaccine candidate on HIV acquisition, viral load or progression. These data suggest that future HIV vaccine trials or other HIV prevention trials associated with HIV prevention should take prior HSV-2 infection into account in study design and analysis.

Our findings support and extend data from prior studies of the epidemiology of HSV-2 among MSM. The 30% overall prevalence of HSV-2 infection in this cohort of high risk MSM reflects substantial regional heterogeneity, with HSV-2 prevalence in Latin America and the Caribbean being almost twice that in North America and Australia. These findings are consistent with previously documented HSV-2 prevalences among HIV negative MSM in the US and Peru.4, 40 Older age, non-white race/ethnicity, and risky sexual behavior are also well recognized HSV-2 risk factors in previous studies among MSM in the Americas.4, 41

This is the first study to our knowledge showing that circumcision is associated with a decreased risk of HSV-2 infection in a cross-sectional cohort of MSM. The 30% reduction in HSV-2 seropositivity among circumcised MSM is consistent with a meta-analysis and recent results from randomized controlled trials among heterosexual men which indicate that circumcision may reduce HSV-2 incidence by up to a third.16, 42, 43 Among MSM, a recent meta-analysis of observational circumcision studies showed no reduction in non-HIV STIs as a combined study outcome, and the three studies that specifically addressed HSV-2 infection also demonstrated no protective effect.44–47 However, of these previous studies, one study used history of genital ulcer disease as the indicator for herpes infection 45 and the other two studies that used HSV-2 serology involved small numbers of circumcised men (82/1306 or 6%)46 and did not adjust for potential confounders47 such as ethnicity, which may have reduced their power to demonstrate an effect.48 The effect of circumcision on HSV-2 acquisition among MSM is complex and further research is needed to verify our findings and estimate the level of protection conferred to insertive and receptive partners.

Preexisting HSV-2 infection was one of the strongest risk factors for HIV acquisition both alone and after accounting for other risk factors among placebo and vaccine recipients in the Step Study. This effect persisted after adjusting for baseline and recent risk behaviors. The 2 to 3-fold increase in HIV risk in this MSM cohort confirms previous observations with prevalent HSV-2 infection in MSM and heterosexuals.4, 11, 15, 41, 49 HSV-2 infection may increase HIV acquisition by genital mucosal disruption that creates a portal of entry for HIV, persistent HIV target cell recruitment, and/or activation and cytokine release which stimulates HIV replication. 8, 50, 51 While the other factors associated with HIV seroconversion in this cohort, young age and unprotected anal sex, are well established determinants of HIV risk, the 4-fold higher risk among MSM in North America and Australia was striking, particularly in light of the lower HSV-2 prevalence and higher male circumcision prevalence among Step volunteers in these regions compared with those in Latin America and the Caribbean. This increased risk appears to reflect differences in risk behaviors and HIV prevalence in the partner pool.

The impact of preexisting HSV-2 infection on HIV viral load, disease progression and transmission remains to be elucidated and could have profound implications for patient management and epidemic control. Meta-analyses suggest both a significantly higher HIV viral load among HIV-1/HSV-2 co-infected individuals than among those without HSV-2 infection52 and a significant survival benefit among HIV infected patients treated with acyclovir.53 Since the HSV-2 effects on HIV may be mediated by up-regulation of HIV due to viral trans-activation and/or increases in pro-inflammatory cytokines, we hypothesized that HSV-2 infection might alter the effect of the MRKAd5 cell mediated vaccine on viral dynamics and HIV disease progression. While not statistically significant, the mean increase in HIV viral load among HSV-2 seropositive compared to seronegative volunteers in this trial (0.2 log10 copies/ml) echoes the viral load meta-analysis results (0.23 log10; 95% CI 0.03 to 0. 44).52 While we found no difference in viral load or time to ART initiation associated with HSV-2 seropositivity among vaccine or placebo recipients, this may be an effect that increases over time with chronic immune activation.

With its rigorous assessment of cofactors for HIV acquisition, including baseline and recent risk behavior, type-specific HSV testing, and on-going longitudinal follow-up of large numbers of volunteers from 34 international sites, the Step Study has not only offered new insights into HIV immunity and cell mediated vaccines, but has expanded our understanding of the epidemiology of HSV-2 infection and its potential role in HIV acquisition and disease progression among MSM. The dynamic nature of HSV-2 and the synergistic role it plays in HIV-1 acquisition and disease make it an ongoing compelling focus in HIV prevention research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Step Study site volunteers and staff whose valuable and heartfelt participation in the MRKAd5 vaccine trial made this study possible. RVB is grateful for funding from the NCRR/NIH (5 KL2 RR025015) and the Qatar National Research Fund (NPRP 08-068-3-024).

We thank the outstanding statistical support staff at SCHARP particularly Maggie Wang, Alicia Sato, Janne Abullarade and Liza Noonan. For assistance with manuscript preparation we are grateful to Rachel Tompa and Aleta Elliot.

Role of the funding sources

The sponsors of the study were involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the report, and in the decision to submit for publication.

Sources of support: Merck Research Laboratories; the Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, in the US National Institutes of Health (NIH); and the NIH-sponsored HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN).

Footnotes

Meetings at which parts of the data were presented:

1. IAS, July 2009, Cape Town, South Africa

2. HVTN, Full Group Meeting, November 2008, Seattle

Registered on Clinical Trials.gov - Identifier : NCT00095576 http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00095576?term=merck+and+hiv+vaccine+v520&rank=2

Authors and contributions

JNW and LC conceived the hypothesis and oversaw the project. RVB, JNW and LC led data interpretation and manuscript writing. YH and HJ led the statistical analysis. RM led the laboratory analysis. JF, KEM, MC, DVM and SPB contributed to the data interpretation and manuscript writing. SPB is a co-chair of the Step Study and led the presentation of the analysis and results to the study site staff and volunteers.

References

- 1.Looker KJ, Garnett GP, Schmid GP. An estimate of the global prevalence and incidence of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. Bull World Health Organ. 2008 Oct;86(10):805–812, A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.046128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss H. Epidemiology of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in the developing world. Herpes. 2004 Apr;11(Suppl 1):24A–35A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu F, Sternberg MR, Kottiri BJ, et al. Trends in herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 seroprevalence in the United States. Jama. 2006 Aug 23;296(8):964–973. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.8.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lama JR, Lucchetti A, Suarez L, et al. Association of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection and syphilis with human immunodeficiency virus infection among men who have sex with men in Peru. J Infect Dis. 2006 Nov 15;194(10):1459–1466. doi: 10.1086/508548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corey L, Wald A. Genital Herpes. In: Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Stamm WE, et al., editors. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 4. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wald A, Zeh J, Selke S, et al. Reactivation of genital herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in asymptomatic seropositive persons. N Engl J Med. 2000 Mar 23;342(12):844–850. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003233421203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mark KE, Wald A, Magaret AS, et al. Rapidly cleared episodes of herpes simplex virus reactivation in immunocompetent adults. J Infect Dis. 2008 Oct 15;198(8):1141–1149. doi: 10.1086/591913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corey L, Woodward A, Klock A, et al. Genital HSV-2 Infection Imprints a Marked Enrichment and Long Term Persistence of HIV Receptor Positive Cells in the Genital Tract: Implications for Microbicide and Vaccine Studies. Paper presented at: Keystone Symposia: Prevention of HIV/AIDS; March 22–March 27, 2009; Keystone, Colorado: Keystone Resort; 2009. Plenary presentation. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schiffer JT, Abu-Raddad L, Mark EK, et al. Frequent Release of Low Amounts of Herpes Simplex Virus from Neurons: Results of a Mathematical Model. Sci Transl Med. 2009 Nov 18;1(7):7ra 16. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mertz GJ, Benedetti J, Ashley R, Selke SA, Corey L. Risk factors for the sexual transmission of genital herpes. Ann Intern Med. 1992 Feb 1;116(3):197–202. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-3-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corey L, Wald A, Celum CL, Quinn TC. The effects of herpes simplex virus-2 on HIV-1 acquisition and transmission: a review of two overlapping epidemics. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004 Apr 15;35(5):435–445. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200404150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wald A, Corey L. How does herpes simplex virus type 2 influence human immunodeficiency virus infection and pathogenesis? J Infect Dis. 2003 May 15;187(10):1509–1512. doi: 10.1086/374976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Celum C, Levine R, Weaver M, Wald A. Genital herpes and human immunodeficiency virus: Double trouble. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2004 Jun;82(6):447–453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wasserheit JN. Epidemiological synergy. Interrelationships between human immunodeficiency virus infection and other sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. 1992 Mar-Apr;19(2):61–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freeman EE, Weiss HA, Glynn JR, Cross PL, Whitworth JA, Hayes RJ. Herpes simplex virus 2 infection increases HIV acquisition in men and women: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Aids. 2006 Jan 2;20(1):73–83. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000198081.09337.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Taljaard D, Lissouba P, et al. Effect of HSV-2 serostatus on acquisition of HIV by young men: results of a longitudinal study in Orange Farm, South Africa. J Infect Dis. 2009 Apr 1;199(7):958–964. doi: 10.1086/597208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahiane SG, Legeai C, Taljaard D, et al. Transmission probabilities of HIV and herpes simplex virus type 2, effect of male circumcision and interaction: a longitudinal study in a township of South Africa. Aids. 2009 Jan 28;23(3):377–383. doi: 10.1097/qad.0b013e32831c5497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duffus WA, Mermin J, Bunnell R, et al. Chronic herpes simplex virus type-2 infection and HIV viral load. Int J STD AIDS. 2005 Nov;16(11):733–735. doi: 10.1258/095646205774763298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray RH, Li X, Wawer MJ, et al. Determinants of HIV-1 load in subjects with early and later HIV infections, in a general-population cohort of Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2004 Apr 1;189(7):1209–1215. doi: 10.1086/382750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mole L, Ripich S, Margolis D, Holodniy M. The impact of active herpes simplex virus infection on human immunodeficiency virus load. J Infect Dis. 1997 Sep;176(3):766–770. doi: 10.1086/517297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serwadda D, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus acquisition associated with genital ulcer disease and herpes simplex virus type 2 infection: a nested case-control study in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2003 Nov 15;188(10):1492–1497. doi: 10.1086/379333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schacker T, Zeh J, Hu H, Shaughnessy M, Corey L. Changes in plasma human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA associated with herpes simplex virus reactivation and suppression. J Infect Dis. 2002 Dec 15;186(12):1718–1725. doi: 10.1086/345771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mellors JW, Kingsley LA, Rinaldo CR, Jr, et al. Quantitation of HIV-1 RNA in plasma predicts outcome after seroconversion. Ann Intern Med. 1995 Apr 15;122(8):573–579. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-8-199504150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Sewankambo N, et al. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000 Mar 30;342(13):921–929. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Celum C, Wald A, Hughes J, et al. Effect of aciclovir on HIV-1 acquisition in herpes simplex virus 2 seropositive women and men who have sex with men: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008 Jun 21;371(9630):2109–2119. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60920-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Celum C, Wald A, Lingappa JR, et al. Acyclovir and Transmission of HIV-1 from Persons Infected with HIV-1 and HSV-2. N Engl J Med. 2010 Feb 4;362(5):427–439. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watson-Jones D, Weiss HA, Rusizoka M, et al. Effect of herpes simplex suppression on incidence of HIV among women in Tanzania. N Engl J Med. 2008 Apr 10;358(15):1560–1571. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu J, Hladik F, Woodward A, et al. Persistence of HIV-1 receptor-positive cells after HSV-2 reactivation is a potential mechanism for increased HIV-1 acquisition. Nat Med. 2009 Aug;15(8):886–892. doi: 10.1038/nm.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buchbinder SP, Mehrotra DV, Duerr A, et al. Efficacy assessment of a cell-mediated immunity HIV-1 vaccine (the Step Study): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, test-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2008 Nov 29;372(9653):1881–1893. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61591-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duerr A, Huang Y, Buchbinder S, et al. Extended follow-up of participants in a cell-mediated immunity HIV vaccine trial (Step study) suggests that the vaccine-associated increased risk of HIV acquisition wanes over time. 2011. In preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. [Accessed 2/15/11, 2011];Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. 2011 http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf.

- 32.World Health Organization. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents: recommendations for a public health approach. Geneva, Switzerland: 2010. – 2010 rev. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599764_eng.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hammer SM, Eron JJ, Jr, Reiss P, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2008 recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA panel. JAMA. 2008 Aug 6;300(5):555–570. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashley RL, Militoni J, Lee F, Nahmias A, Corey L. Comparison of Western blot (immunoblot) and glycoprotein G-specific immunodot enzyme assay for detecting antibodies to herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in human sera. J Clin Microbiol. 1988 Apr;26(4):662–667. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.4.662-667.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venables WN, Ripley BD. Modern Applied Statistics with S. 4. Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stata/SE 10.0 [computer program] College Station, TX, USA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grambsch P, Therneau T. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81:515–526. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res. 2007 Jun;16(3):219–242. doi: 10.1177/0962280206074463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tabet SR, Krone MR, Paradise MA, Corey L, Stamm WE, Celum CL. Incidence of HIV and sexually transmitted diseases (STD) in a cohort of HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM) Aids. 1998;12(15):2041–2048. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199815000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Renzi C, Douglas JM, Jr, Foster M, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 2 infection as a risk factor for human immunodeficiency virus acquisition in men who have sex with men. J Infect Dis. 2003 Jan 1;187(1):19–25. doi: 10.1086/345867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weiss HA, Thomas SL, Munabi SK, Hayes RJ. Male circumcision and risk of syphilis, chancroid, and genital herpes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2006 Apr;82(2):101–109. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.017442. discussion 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tobian AA, Serwadda D, Quinn TC, et al. Male circumcision for the prevention of HSV-2 and HPV infections and syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2009 Mar 26;360(13):1298–1309. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Millett GA, Flores SA, Marks G, Reed JB, Herbst JH. Circumcision status and risk of HIV and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis. Jama. 2008 Oct 8;300(14):1674–1684. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kreiss JK, Hopkins SG. The association between circumcision status and human immunodeficiency virus infection among homosexual men. J Infect Dis. 1993;168(6):1404–1408. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.6.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanchez J. The Cener for HIV Identification, PRevention and Treatment Services (CHIPTS) The Future Direction of MAle Circumcision in HIV Prevention working ocnference. Vol Los Angeles, CA: 2007. Cutting the edge of the HIV epidemic among MSM. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Templeton DJ, Jin F, Prestage GP, et al. The International Society for Sexually Transmitted Disease Research. Vol Seattle, WA: 2007. Circumcision and risk of sexually transmitted diseases in the HIM cohort of homosexual men in Sydney, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Templeton DJ, Mao L, Prestage G, Kaldor JM, Kippax S, Grulich AE. Demographic predictors of circumcision status in a community-based sample of homosexual men in Sydney, Australia. Sex Health. 2006 Sep;3(3):191–193. doi: 10.1071/sh06009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown EL, Wald A, Hughes JP, et al. High risk of human immunodeficiency virus in men who have sex with men with herpes simplex virus type 2 in the EXPLORE study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006 Oct 15;164(8):733–741. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Celum CL. The interaction between herpes simplex virus and human immunodeficiency virus. Herpes. 2004 Apr;11(Suppl 1):36A–45A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Palu G, Benetti L, Calistri A. Molecular basis of the interactions between herpes simplex viruses and HIV-1. Herpes. 2001 Jul;8(2):50–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barnabas RV, Weiss HA, Wasserheit JN. ISSTDR. Vol London, UK: 2009. Role of Co-infections in HIV epidemic trajectory and positive prevention: A systematic review and meta-analysis of malaria, HSV-2 and TB co-infections. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ioannidis JP, Collier AC, Cooper DA, et al. Clinical efficacy of high-dose acyclovir in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: a meta-analysis of randomized individual patient data. J Infect Dis. 1998 Aug;178(2):349–359. doi: 10.1086/515621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.