It would be somewhat of an understatement to assert that the notion of ars medicina has been substantially transformed from its classical definition as the art of healing. Practitioners of modern medicine would probably be more inclined to refer to themselves as practising the science of medicine, dispatching all other forms of treatment to the shamanistic margins where abide “traditional,” “alternative,” or “complementary” medicines such as acupuncture, homeopathy, naturopathy, herbalism and bush or tribal remedies.

Then there is Islamic medicine, an altogether tricky term to pin down. Some believe it to be a comprehensive form of medicine based on a complete system of theory and practice. Others say it’s largely a medieval notion that has been abandoned by all but the most tribal Muslims as the Arab World moves inexorably into the 21st century. Still others view it in prophetic terms, as having been crafted from the central religious text and core source of all knowledge in Islam, the Qur’an, with natural remedies for most ailments and specific prayers that must be recited for any disease to be conquered.

Historically, Islamic medicine is believed to be a body of knowledge cultivated largely from the first eight centuries and based primarily on Greek sources, Dr. Husain Nagamia, chairman of the Brandon, Florida–based International Institute of Islamic Medicine wrote in the Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine (www.ishim.net/ishimj/4/04.pdf). It was built incrementally into a type of medicine before being subsumed, as were most other forms of religious prescription, by the birth of modern medicine during the European renaissance.

But a form of Islamic medicine, known as unani tibb (from unani, the Arabic word for Ionian or Greek, and tibb, the Arabic word for medicine), continues to be practised to this day in countries such as India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, Nagamia wrote. Some medical schools in India offer degrees in unani medicine and several countries continue to license and regulate its practitioners. As part of an effort to benchmark training for traditional, complementary and alternative medicine, the World Health Organization has even issued guidelines to promote “safety, efficacy and quality” in unani medicine and support “national health authorities in the establishment of adequate laws, rules, and licensing practices” (http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s17558en/s17558en.pdf).

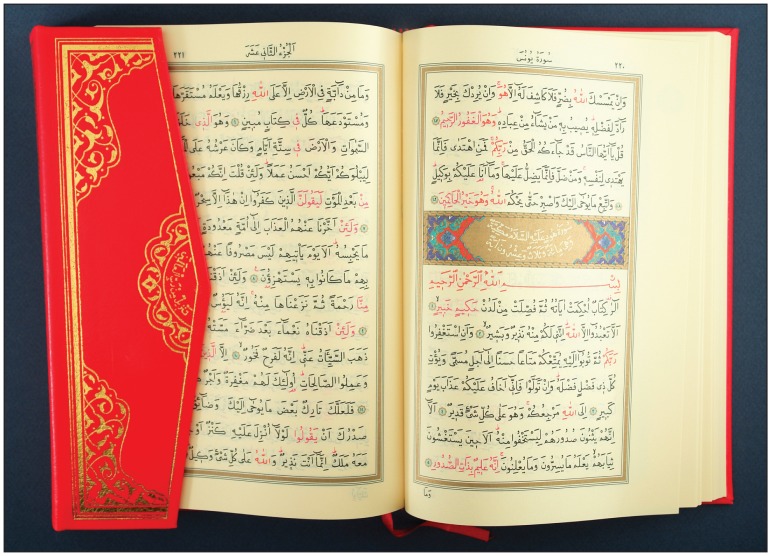

Some view Islamic medicine in prophetic terms, as having been crafted from the Qur’an, with natural remedies for most ailments and specific prayers to conquer disease.

Image courtesy of © 2012 Thinkstock

Although the practice of unani medicine has been largely relegated to rural communities in South Asia, Omar Hasan Kasule, Sr., professor of epidemiology and Islamic medicine at the University of Brunei Darussalam in Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei, writes in an email that a broader concept of Islamic medicine is enjoying a renaissance of its own.

Kasule defined that concept in a paper for the International Medical Journal (for which he was the founding chief editor) as being “medicine whose basic paradigms, concepts, values, and procedures conform to or do not contradict the Qur’an and Sunnah [clear and well-trodden path]. It is not specific medical procedures or therapeutic agents used in a particular place or a particular time. Islamic medicine is universal, all-embracing, flexible, and allows for growth and development of various methods of investigating and treating diseases within the frame-work described above” (www.eimjm.com/Vol4-No1/Vol4-No1-H2.htm).

Kasule also contended that any medical system that meets the moral criteria of Islam falls within the purview of Islamic medicine. Systems that don’t conform, he writes in an email, can be “Islamized” by requiring them to instill Islamic values and remove those aspects that don’t mesh with such values. In this sense, what distinguishes Islamic hospitals and medical schools from others is not necessarily the procedures and treatments being used, but “the ethical, social, and spiritual values that their physicians and nurses believe in and practice,” Kasule added.

Yet, while Kasule believes that Islamic medicine stands poised to make a splash, current practice of the primary extant variant, unani medicine, is largely confined to a few countries.

For the most part, it is a complementary form of practice used mainly in the treatment of common ailments, says Ibrahim Syed, president of the Islamic Research Foundation International, Inc., based in Louisville, Kentucky. Patients with more serious conditions are usually referred to advanced medical centres, he adds.

Unani medicine is primarily based on the Greek notion of the four humours, according to a paper on the history and practice of unani medicine by Helen Sheehan, an affiliated faculty member of the South Asia Center at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and Dr. S.J. Hussain, former director of the Central Research Institute of Unani Medicine in Hyderabad, India (Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 2002;583: 122-35). It posits that health and temperament are tied to four fluids in the human body: phlegm, blood, yellow bile and black bile. The manner in which the four substances balance within the body determine an individual’s temperament, with dominance of one substance manifesting itself in the form of a phlegmatic, sanguine, choleric or melancholic temperament, respectively.

An individual is in good health when the humours are in balance. Conversely, an excess or deficit of one or more fluids is the cause of sickness — the body’s struggle to return to a state of equilibrium, Sheehan and Hussain wrote. Treatment of the ill, therefore, involves measures intended to restore balance to the four humours. As diagnosis necessitates determining which humour is out of balance, assessment is accomplished by identifying a patient’s temperament, examining the pulses and conducting urine and stool analyses.

The external environment is also viewed as an important variable in the maintenance of equilibrium, so treatment typically involves an effort to “keep the human body attuned to the various changes in climate and geography by regulating diet, sleep, activity, bathing, and so forth,” Sheehan and Hussain added. Other treatment options include surgery or the use of herbal, mineral or other natural remedies.

Another set of treatments that falls under the rubric of unani therapy is detoxification of the body by removing waste materials through such procedures as venesection or phlebotomy, which involves surgical incision of a vein to remove small amounts of blood, which is believed to be effective in the treatment of conditions such as high blood pressure, hemorrhoids and scabies, according to the paper. Similarly, emetics are used to induce vomiting and treat headaches, tonsillitis, migraines and other ailments, while “cupping” uses a suction device to draw blood to the surface of the skin which can then be drained as part of treatment for infection.

Muslim historians and physicians draw a line between Islamic medicine and “prophetic” medicine, which they refer to as a collection of “hadiths” or accounts of the sayings and actions of the prophet Muhammad that are related to sickness, diet, hygiene and other aspects or determinants of health, wrote Nagamia in his paper on the history and current practice of Islamic medicine. For instance, several hadiths assert that there is a remedial value in honey. According to another hadith — “I heard Allah’s Apostle saying, ‘There is healing in black cumin for all diseases except death’” — nigella sativa, or black seed, is a cure-all (www.2muslims.com/directory/hadith/bukhari/7/592/).

Prophetic medicine is distinct from traditional Islamic medicine because it lacks a scientific basis, Nagamia says. In prophetic medicine, there’s no need to explain why or how remedies work because they are considered credible solely on the basis that they originated from Mohammad, he explains.

Although Islamic medicine may have been essentially ousted from most health care systems, it laid a foundation for many aspects of preventive medicine, Nagamia adds. “When you talk about modern medicine, it does not necessarily mean you shelf all of these other ideas. Ideas of diet, prevention, cessation of smoking, cessation of alcoholism — all of these are also very important in modern medicine, and this is inherited from the basis that was laid during the time of Islamic medicine.”