Abstract

Background

Vitamin D insufficiency is associated with suboptimal health. The prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency may be rising, but population-based trends are uncertain. We sought to evaluate US population trends in vitamin D insufficiency.

Methods

We compared serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) levels from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), collected during 1988 through 1994, with NHANES data collected from 2001 through 2004 (NHANES 2001–2004). Complete data were available for 18 883 participants in NHANES III and 13 369 participants in NHANES 2001–2004.

Results

The mean serum 25(OH)D level was 30 (95% confidence interval [CI], 29–30) ng/mL during NHANES III and decreased to 24 (23–25) ng/mL during NHANES 2001–2004. Accordingly, the prevalence of 25(OH)D levels of less than 10 ng/mL increased from 2% (95% CI, 2%–2%) to 6% (5%–8%), and 25(OH)D levels of 30 ng/mL or more decreased from 45% (43%–47%) to 23% (20%–26%). The prevalence of 25(OH)D levels of less than 10 ng/mL in non-Hispanic blacks rose from 9% during NHANES III to 29% during NHANES 2001–2004, with a corresponding decrease in the prevalence of levels of 30 ng/mL or more from 12% to 3%. Differences by age strata (mean serum 25[OH]D levels ranging from 28–32 ng/mL) and sex (28 ng/mL for women and 32 ng/mL for men) during NHANES III equalized during NHANES 2001–2004 (24 vs 24 ng/mL for age and 24 vs 24 ng/mL for sex).

Conclusions

National data demonstrate a marked decrease in serum 25(OH)D levels from the 1988–1994 to the 2001–2004 NHANES data collections. Racial/ethnic differences have persisted and may have important implications for known health disparities. Current recommendations for vitamin D supplementation are inadequate to address the growing epidemic of vitamin D insufficiency.

In the past, many health care professionals believed that the major health problems resulting from vitamin D deficiency were rickets in children1 and osteomalacia in adults,2 which were greatly reduced by the fortification of foods with vitamin D. Recently, there has been intense interest in the role of vitamin D in a variety of nonskeletal medical conditions. Indeed, vitamin D insufficiency has been associated with increases in cardiovascular disease,3–5 cancer,6–9 and infection.10–13 Vitamin D supplementation appears to mitigate the incidence and adverse outcomes of these diseases and may reduce all-cause mortality.14–17

The Institute of Medicine currently recommends vitamin D supplementation of 200 IU/d from birth to 50 years of age, 400 IU/d for adults aged 51 to 70 years, and 600 IU/d for adults 71 years or older.18 However, these recommendations appear limited by the goals of treatment, which focus primarily on bone health. Until recently, serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) levels of 20 ng/mL or more (to convert to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 2.496) appeared adequate based on improved skeletal outcomes, but increasing evidence suggests that 30 ng/mL or even 40 ng/mL may be required for optimum health.19–25 Indeed, several authors argue that current recommended doses of vitamin D supplementation are woefully inadequate to meet higher serum 25(OH)D levels on a population level.22,26–28

Sunlight exposure is the primary determinant of vitamin D status in humans and, particularly in northern latitudes from November to March, there are insufficient UV-B rays to produce vitamin D.29 Successful campaigns to control sun exposure through avoidance and sun protection, coupled with decreases in outdoor physical activity, may have increased the prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency.29,30 In addition, because many studies of vitamin D have focused on particular subgroups (ie, older adults, women, and racial subgroups), the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) has served as the primary source of population-based prevalence data for vitamin D status in the United States.31,32 Because these data were collected from 1988 to 1994, changes in prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency during the past decade could affect national recommendations about vitamin D status.

Trends of serum 25(OH)D levels in the US population, particularly for direct comparison with older data, have not been previously reported. In this study, we sought to compare the prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency in 1988 through 1994 with that in 2001 through 2004, using NHANES data. In addition, we evaluated changes in known demographic disparities in vitamin D insufficiency, with particular emphasis on populations at increased risk, including older adults, women, and individuals of non-white race/ethnicity.

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN AND PARTICIPANTS

Every year, the National Center for Health Statistics conducts the NHANES, a nationally representative probability sample of the noninstitutionalized US civilian population. Initially, NHANES data were released in large blocks of 6 to 7 years; the most recent of these releases was NHANES III, collected from 1988 to 1994. Starting in January 1999, NHANES data were released in 2-year cycles. We received a waiver from our institutional review board to analyze NHANES III and the 2 most recent cycles of released NHANES data (ie, data collected from January 2001 through December 2004, hereinafter referred to as NHANES 2001–2004).

Details of survey methods are described elsewhere.33 Briefly, the sample is obtained by using a complex, stratified, multistage probability study design with unequal probabilities of selection. Certain subgroups of people are oversampled in NHANES, including low-income persons, adolescents aged 12 to 17 years, adults 60 years or older, African Americans, and Mexican Americans. The NHANES sampling strategy uses 4 stages covering geographic primary sampling units, which are counties or small groups of contiguous counties, segments within primary sampling units (a block or group of blocks), households within segments, and 1 or more participants within households.

From 1988 to 1994, NHANES III collected household interview data, including demographic characteristics and data on health and nutrition for 22 266 of 27 145 invited participants aged 12 or older (82%). Of these, most (19 784 [89%]) subsequently received physical and laboratory examinations in a mobile examination center or at a home visit. We limited our analysis to these 18 883 participants with reported serum 25(OH)D values (901 missing), who represented 195 million Americans. During 2001 to 2004, NHANES collected household interview data for 15 242 of 19 275 invited participants 12 years or older (79%). Subsequently, 14 435 of these (95%) received physical and laboratory examinations in a mobile examination center, and 13 369 participants (88%) underwent measurement of serum 25(OH)D levels (1066 missing), which represented 221 million Americans.

Strategies for sampling and methods of data collection were very similar to maintain consistency and facilitate comparisons throughout the NHANES years. In particular, because physical and laboratory examinations occurred in mobile examination centers, inclement weather was an issue during data collection. To avoid these issues and improve response, the NHANES mobile examination centers preferentially scheduled data collection in the lower latitudes (further south) during the winter months and in higher latitudes (further north) during the summer months, a strategy that was used consistently in all years of NHANES data collection.

DATA COLLECTION

Blood samples for serum 25(OH)D testing collected during the examination were centrifuged, divided into aliquots, and frozen to −70°C on site and then shipped on dry ice to central laboratories, where they were stored at −70°C until analysis. Serum 25 (OH)D levels were measured by a radioimmunoassay kit after extraction with acetonitrile (DiaSorin, Stillwater, Minnesota) by the National Center for Environmental Health (Atlanta, Georgia). Because risk factors for vitamin D insufficiency have been extensively explored in previous NHANES analyses,30 we focused the current analysis on self-reported age, sex, and race/ethnicity collected during the household interview to evaluate changes in previously documented demographic disparities in vitamin D insufficiency.31,32 Because the month of data collection was not publicly reported in NHANES 2001–2004 (owing to protection of confidentiality), we did not record or control for season.

ANALYSIS

We performed statistical analyses using commercially available software (Stata, version 9.0; StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Using survey commands, we applied the recommended sub-sample weights for the interview plus examination data to account for unequal probabilities of selection and to represent accurate estimates for the US population. All results are presented as weighted values. We calculated variance on the basis of NHANES-provided masked variance units, using the Taylor series linearization method. We categorized serum 25(OH)D levels as less than 10 ng/mL and 30 ng/mL or more.22,26 Primary analysis is descriptive, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical comparisons used difference of means or proportions of 25 (OH)D levels with 95% CIs to facilitate interpretation of clinically and statistically significant differences.

RESULTS

Table 1 displays major demographic characteristics and serum 25(OH)D levels from the NHANES III and NHANES 2001–2004 samples. Overall, the mean serum 25(OH)D level in the US population was 30 (95% CI, 29–30) ng/mL during the 1988–1994 collection and deceased to 24 (23–25) ng/mL during the 2001–2004 collection.

Table 1.

Description of Demographics and Serum 25(OH)D Levels in NHANES III and NHANES 2001–2004

| NHANES III (1988–1994)a |

NHANES 2001–2004a |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Participants | Estimated US Population, Millions | % of Participants (95% CI)b | No. of Participants | Estimated US Population, Millions | % of Participants (95% CI)b | |

| Total | 18 883 | 195 | 100 | 13 369 | 221 | 100 |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 12–19 | 2937 | 26 | 13 (13–14) | 4224 | 29 | 13 (12–14) |

| 20–39 | 6455 | 77 | 40 (38–42) | 3249 | 75 | 34 (32–36) |

| 40–59 | 4293 | 54 | 28 (27–29) | 2726 | 74 | 34 (32–35) |

| ≥60 | 5198 | 37 | 19 (17–21) | 3170 | 41 | 19 (18–20) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 8840 | 94 | 48 (48–49) | 6512 | 107 | 49 (48–49) |

| Female | 10 043 | 101 | 52 (51–52) | 6856 | 114 | 51 (51–52) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| NH white | 7428 | 146 | 75 (72–78) | 6131 | 158 | 72 (67–76) |

| NH black | 5362 | 22 | 11 (10–13) | 3149 | 25 | 11 (9–14) |

| Mexican American | 5305 | 11 | 6 (5–7) | 3211 | 18 | 8 (6–11) |

| Other | 788 | 16 | 8 (7–10) | 878 | 20 | 9 (7–12) |

| 25(OH)D level, ng/mL | ||||||

| <10 | 684 | 4 | 2 (2–2) | 1321 | 14 | 6 (5–8) |

| 10 to <30 | 12 302 | 104 | 53 (51–55) | 9843 | 157 | 71 (68–73) |

| ≥30 | 5897 | 87 | 45 (43–47) | 2205 | 50 | 23 (20–26) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NH, non-Hispanic; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

SI conversion factor: To convert 25(OH)D to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 2.496.

Some columns do not add to the totals because of missing data or rounding.

Estimated percentages of the US population, based on application of NHANES-provided survey weights.

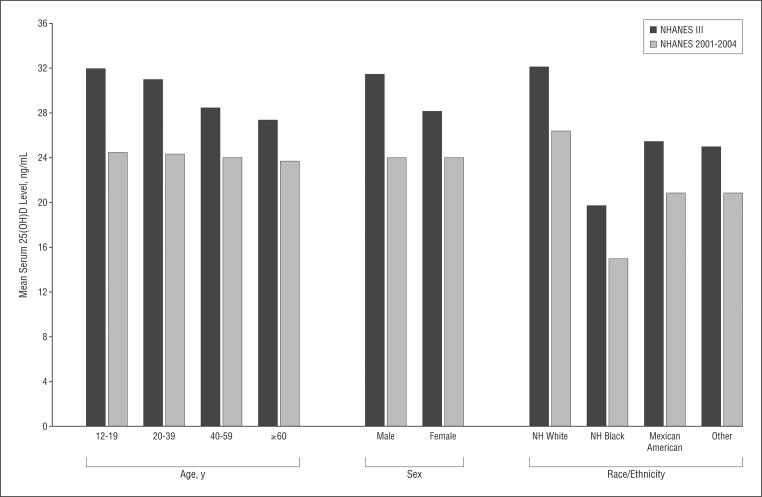

Figure 1 illustrates the changes in mean serum 25 (OH)D levels from NHANES III to NHANES 2001–2004. Differences in mean serum 25(OH)D levels by age that were present in 1988 to 1994 nearly equalized by 2001 to 2004. Specifically, mean levels in NHANES III ranged from 28 ng/mL for subjects 60 years or older to 32 ng/mL for those aged 12 to 19 years (difference, 4 [95% CI, 3–6] ng/mL). However, by NHANES 2001–2004, these mean levels were similar, ranging from 24 ng/mL for subjects 60 years or older to 24 ng/mL for those aged 12 to 19 years (difference, 1 [95% CI, 0–2] ng/mL). Likewise, the lower mean serum 25(OH)D level for females in NHANES III (32 vs 28 ng/mL for males and females, respectively; difference, 4 [95% CI, 3–4] ng/mL) equalized in NHANES 2001–2004 (24 vs 24 ng/mL, respectively; difference, 0 [95% CI, 0–1] ng/mL). By contrast, vitamin D-level differences by race/ethnicity (ie, the lower mean serum 25[OH]D levels in non-Hispanic blacks and to a lesser extent Mexican-Americans and those of other race/ethnicity, compared with non-Hispanic whites) have persisted over time (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) levels in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) (1988–1994) and in NHANES 2001–2004, stratified by demographic characteristics. NH indicates non-Hispanic. To convert 25(OH)D levels to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 2.496.

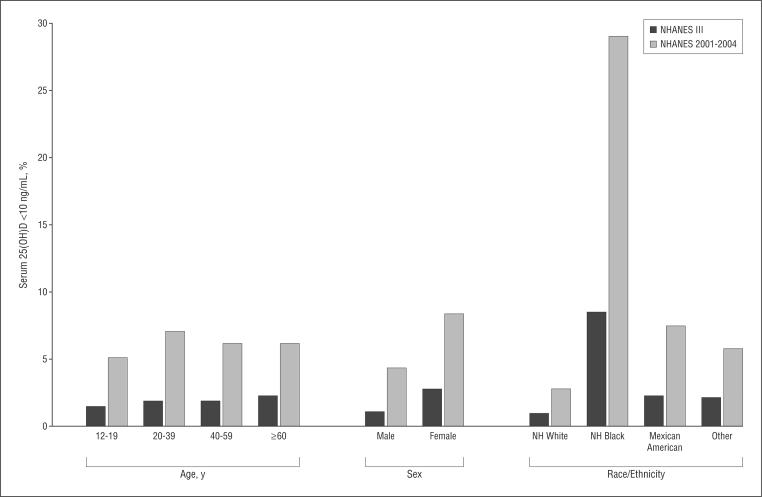

Figure 2 demonstrates the increasing prevalence of serum 25(OH)D levels of less than 10 ng/mL in the US population. Overall, the prevalence of 25(OH)D of less than 10 ng/mL increased 3-fold, from 2% in NHANES III to 6% in NHANES 2001–2004 (difference, 4% [95% CI, 3%–6%]). In addition, the prevalence of 25(OH)D of less than 20 ng/mL increased from 22% to 36% (difference, 14% [95% CI, 10%–18%]). Although all demographic sub-groups had increases in 25(OH)D levels of less than 10 ng/mL, existing disparities by older age essentially disappeared, whereas those by female sex and nonwhite race/ethnicity persisted. Notably, the prevalence of 25(OH)D levels of less than 10 ng/mL in non-Hispanic blacks rose from 9% in NHANES III to 29% in NHANES 2001–2004 (difference, 20% [95% CI, 16%–24%]).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) level of less than 10 ng/mL in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) (1988–1994) and in NHANES 2001–2004, stratified by demographic characteristics. NH indicates non-Hispanic. To convert 25(OH)D levels to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 2.496.

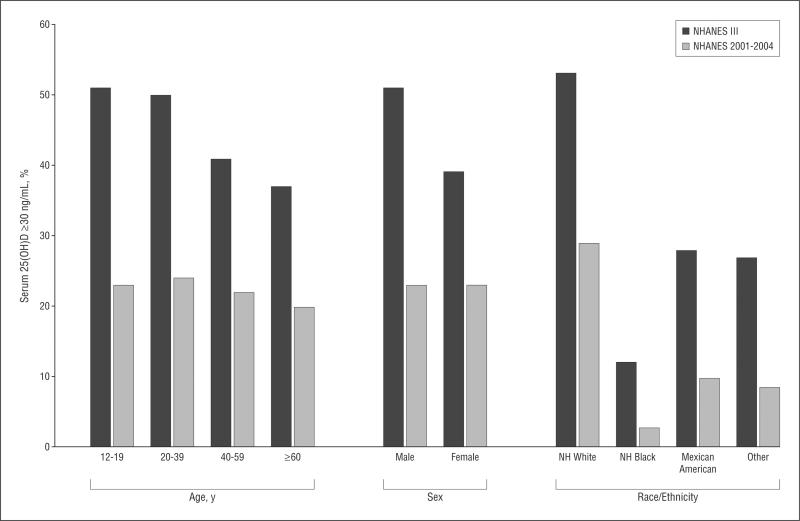

Figure 3 illustrates the marked decrease in serum 25 (OH)D levels of 30 ng/mL or more. Overall, the prevalence of 25(OH)D levels of 30 ng/mL or more decreased by approximately half from 45% in NHANES III to 23% in NHANES 2001–2004 (difference, 22% [95% CI, 19%–26%]). Disparities by age and sex leveled, as illustrated in Figure 3, but again, the disparities by race/ethnicity persisted. Of particular note, the prevalence of 25(OH)D levels of 30 ng/mL or more among non-Hispanic blacks decreased, from 12% in NHANES III to 3% in NHANES 2001–2004 (difference, 9% [95% CI, 7%–11%]).

Figure 3.

Prevalence of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) level of 30 ng/mL or more in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) (1988–1994) and in NHANES 2001–2004, stratified by demographic characteristics. NH indicates non-Hispanic. To convert 25(OH)D levels to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 2.496.

A detailed stratification of serum 25(OH)D levels by demographic characteristics is presented in Table 2 (stratification by alternate 25[OH]D thresholds is available on request from the authors). There was a trend toward lower serum 25(OH)D levels with increasing age for non-Hispanic whites and Mexican-Americans. This trend appeared stronger in NHANES III compared with NHANES 2001–2004. Non-Hispanic blacks did not have this inverse association between age and serum 25(OH)D levels. In addition, serum 25(OH)D levels were lowest for those aged 20 to 39 years among non-Hispanic blacks.

Table 2.

Mean 25(OH)D Levels and Prevalence of Levels of Less Than 10 ng/mL and of 30 ng/mL or More in NHANES III vs NHANES 2001–2004 by Age, Sex, and Race/Ethnicity

| NHANES III (1988–1994) |

NHANES 2001–2004 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean 25(OH)D Level, ng/mL (95% CI) | Percentage of Participants (95% CI) |

Mean 25(OH)D Level, ng/mL (95% CI) | Percentage of Participants (95% CI) |

|||

| <10 ng/mL | ≥30 ng/mL | <10 ng/mL | ≥30 ng/mL | |||

| NH white males, age, y | ||||||

| 12–19 | 38 (36–40) | 0 | 71 (62–78) | 28 (27–29) | <1 (NC) | 33 (28–39) |

| 20–39 | 35 (34–36) | <1 (NC) | 63 (59–67) | 26 (25–27) | 2 (NC) | 29 (24–35) |

| 40–59 | 32 (31–33) | <1 (NC) | 54 (49–59) | 26 (25–28) | 1 (NC) | 29 (23–36) |

| ≥60 | 31 (30–32) | <1 (NC) | 49 (46–53) | 25 (24–26) | 2 (NC) | 23 (19–27) |

| NH white females, age, y | ||||||

| 12–19 | 34 (32–36) | <1 (NC) | 61 (54–67) | 28 (26–29) | <1 (NC) | 32 (27–38) |

| 20–39 | 34 (32–36) | <1 (NC) | 59 (53–64) | 28 (27–30) | 3 (NC) | 37 (33–41) |

| 40–59 | 29 (28–30) | 1 (NC) | 41 (37–45) | 25 (24–26) | 5 (4–7) | 26 (21–31) |

| ≥60 | 26 (26–27) | 3 (2–4) | 32 (29–35) | 25 (24–25) | 6 (4–8) | 24 (21–28) |

| NH black males, age, y | ||||||

| 12–19 | 24 (22–25) | 4 (NC) | 25 (19–31) | 17 (16–18) | 19 (14–24) | 4 (NC) |

| 20–39 | 20 (19–22) | 6 (4–8) | 13 (10–18) | 15 (14–16) | 27 (21–35) | 2 (NC) |

| 40–59 | 21 (20–22) | 6 (NC) | 13 (10–16) | 16 (16–18) | 18 (14–23) | 4 (NC) |

| ≥60 | 22 (21–23) | 5 (NC) | 19 (15–25) | 17 (16–18) | 20 (15–27) | 3 (NC) |

| NH black females, age, y | ||||||

| 12–19 | 18 (17–20) | 10 (7–15) | 8 (5–11) | 14 (14–15) | 30 (25–43) | 2 (NC) |

| 20–39 | 18 (17–19) | 12 (9–16) | 7 (6–10) | 14 (13–14) | 37 (31–43) | 2 (NC) |

| 40–59 | 18 (17–19) | 10 (8–14) | 8 (6–11) | 14 (13–15) | 38 (32–44) | 2 (NC) |

| ≥60 | 20 (18–21) | 11 (7–16) | 11 (9–14) | 16 (15–18) | 26 (21–31) | 6 (NC) |

| Mexican American males, age, y | ||||||

| 12–19 | 29 (28–30) | <1 (NC) | 41 (32–51) | 23 (22–24) | 3 (NC) | 11 (8–16) |

| 20–39 | 28 (27–29) | 2 (NC) | 38 (33–43) | 22 (21–23) | 4 (NC) | 11 (7–17) |

| 40–59 | 26 (25–27) | 2 (NC) | 32 (27–38) | 22 (20–23) | 4 (NC) | 9 (NC) |

| ≥60 | 26 (25–27) | 1 (NC) | 30 (25–36) | 21 (19–22) | 9 (NC) | 11 (NC) |

| Mexican American females, age, y | ||||||

| 12–19 | 26 (25–26) | 2 (NC) | 24 (21–27) | 20 (19–21) | 7 (4–11) | 6 (4–8) |

| 20–39 | 24 (22–24) | 3 (2–5) | 20 (16–24) | 20 (19–21) | 9 (7–12) | 11 (8–14) |

| 40–59 | 21 (20–22) | 4 (NC) | 14 (11–18) | 18 (17–20) | 16 (12–22) | 8 (NC) |

| ≥60 | 22 (21–23) | 6 (NC) | 18 (13–23) | 19 (17–20) | 16 (10–25) | 5 (NC) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NC, not calculable owing to fewer than 30 observations (point estimates may also be unstable); NH, non-Hispanic; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

SI conversion factor: To convert 25(OH)D to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 2.496.

COMMENT

To our knowledge, we report the first evaluation of temporal trends in vitamin D status in the US population. The NHANES data demonstrate a marked decrease in mean serum 25(OH)D levels from the 1988–1994 to the 2001–2004 collections and a corresponding increase in vitamin D insufficiency across all demographic strata. These findings have important implications for health disparities and public health.

During 2001 to 2004, only 23% of US adolescents and adults had serum 25(OH)D levels of 30 ng/mL or more, the minimum level that appears necessary for general health benefits.22,26 In particular, these higher 25(OH)D levels have been associated with reduced incidence and improved outcomes in cardiovascular disease,3–5 cancer,6–9 and infection.10–13 Furthermore, supplementation appears to mitigate the risk associated with vitamin D insufficiency.14–17

The current analysis describes a much higher prevalence (77% during NHANES 2001–2004) of vitamin D insufficiency in the US population than previously reported.31,32 Changes in population demographics were limited and do not appear to explain the observed increase in prevalence. In addition, NHANES preferentially avoided sampling in northern latitudes during the winter; thus, the true prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency in the US population is likely even higher than we have reported.

Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) is derived from skin exposure to UV-B rays and dietary intake (including supplements). Few foods contain vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol) or vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol),26 and recommended doses of vitamin D supplementation have not changed significantly in the past 2 decades.18Therefore,ingestion is,at most, a small component of the marked change in prevalence.

Because exposure to UV-B rays is the primary determinant of vitamin D status in humans, this is more likely the primary cause of the increasing prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency.29 Although widespread campaigns for sunscreen use and sun avoidance, including Healthy People 2010, have reduced the incidence of skin cancers,34 sunscreen with a sun protection factor of 15 also decreases the synthesis of vitamin D3 by 99%.35 Increased sunscreen use with a higher sun protection factor likely contributed to the reported trend of lower 25(OH)D levels. In addition, decreased outdoor activity and obesity have been associated with vitamin D insufficiency.30,36 The increased inactivity and obesity in the US population has likely contributed to the observed rise in vitamin D insufficiency.37

Previously published data suggested that vitamin D insufficiency was more prevalent among older adults (owing to reduction of 7-dehydrocholesterol levels in skin), women (owing to lower outdoor activity), and individuals with darker skin (owing to increased melanin).26,30,32 We found that previous differences by age and sex have equalized, but those by race/ethnicity have remained. The loss of age- and sex-related differences may be secondary to disproportionately greater time indoors (eg, with television, computers, and video games) and less time outdoors among younger compared with older individuals and males compared with females.

Although socioeconomic status, health care access, lifestyle, and cultural factors contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in disease incidence and outcomes,38 vitamin D insufficiency may provide a plausible biological explanation for health differences. In particular, black and, to a lesser extent, Hispanic Americans have a markedly higher prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency and higher incidence and worse outcomes for cardiovascular disease, certain cancers, diabetes mellitus, and renal disease, all of which have been linked to vitamin D insufficiency.22,26,38 Indeed, Wolf et al39 recently reported that, compared with white patients undergoing dialysis, mortality was 16% lower in black patients receiving vitamin D supplements but 35% higher in black patients not receiving supplements. Randomized trials of vitamin D supplementation in diverse cohorts of patients will help to further evaluate this hypothesis.

As recently suggested,22,26–28 our data provide additional evidence that current recommendations18 for vitamin D supplementation (200–600 IU/d) are inadequate to achieve optimal serum 25(OH)D levels in most of the US population. These recommendations were based on older prevalence data, which had a lower prevalence of suboptimal serum 25(OH)D levels, and were focused on skeletal outcomes, which target lower overall levels than are required for optimal general health.19–25 For instance, 400 or 800 IU/d would raise serum 25(OH)D levels by only approximately 4 or 9 ng/mL, respectively,40 which would be inadequate for many Americans based on the present analysis. Furthermore, current recommendations are stratified by age; however, our data suggest that current serum 25(OH)D levels are similar across the age spectrum.

Recommendations based on race/ethnicity (ie, higher levels of supplementation for blacks) would be more consistent with current population-based data. In addition, although not specifically evaluated in this analysis, recommendations by season and latitude (ie, higher supplementation in the winter and at higher latitudes) would likely be more effective.

This study has some potential limitations. First, methodologic explanations for the increased prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency should be considered. However, data were collected by the same group (the National Center for Health Statistics) using similar methods, a similar sampling technique, and the same 25(OH)D assay, which make this unlikely. In addition, nonresponse bias could have some effect on the results, although the survey weights provided by the National Center for Health Statistics attempt to control for this. We have based our serum 25(OH)D thresholds on previous outcome studies; no outcomes were assessed in this analysis. Serum was collected at only 1 point and preferentially collected in northern states in the summer and southern states in the winter. As a result, the data presented most likely represent the best-case scenario; random sampling across all seasons should yield an even higher prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency. Additional potential limitations are that the demographic information was self-reported and that other factors associated with vitamin D insufficiency were not analyzed (eg, season, latitude, estimated sunlight exposure, and diet). However, because determinants of vitamin D insufficiency have been well described, the purpose of our analysis was to examine the prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency in the US population.

CONCLUSIONS

We found that the mean serum 25(OH)D level in the US population dropped by 6 ng/mL from the 1988–1994 to the 2001–2004 data collections. This drop was associated with an overall increase in vitamin D insufficiency to nearly 3 of every 4 adolescent and adult Americans. Although differences by age and sex have equalized, racial/ethnic differences have persisted and may help to explain known racial/ethnic disparities in cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other major health conditions. Nearly all non-Hispanic blacks (97%) and most Mexican-Americans (90%) now have vitamin D insufficiency.

Current recommendations for dosage of vitamin D supplements are inadequate to address this growing epidemic of vitamin D insufficiency. Increased intake of vitamin D (≥1000 IU/d)—particularly during the winter months and at higher latitudes—and judicious sun exposure would improve vitamin D status and likely improve the overall health of the US population. Large randomized controlled trials of these higher doses of vitamin D supplementation are needed to evaluate their effect on general health and mortality.

Acknowledgments

Role of the Sponsors: The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Funding/Support: Dr Camargo was supported by the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for D-receptor Activation Research and grants R01 HL84401, and Dr Liu was supported by grant R01 AI63184 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Ginde had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Ginde, Liu, and Camargo. Acquisition of data: Ginde. Analysis and interpretation of data: Ginde, Liu, and Camargo. Drafting of the manuscript: Ginde. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Ginde, Liu, and Camargo. Statistical analysis: Ginde. Study supervision: Camargo.

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hess AF, Unger LF. The cure of infantile rickets by sunlight. JAMA. 1921;77(1):39–41. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalmers J, Conacher WDH, Garnder DL, Scott PJ. Osteomalacia: a common disease in elderly women. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1967;49(3):403–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poole KE, Loveridge N, Barker PJ, et al. Reduced vitamin D in acute stroke. Stroke. 2006;37(1):243–245. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000195184.24297.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Hollis BW, Rimm EB. 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of myocardial infarction in men. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(11):1174–1180. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.11.1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dobnig H, Pilz S, Scharnagl H, et al. Independent association of low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(12):1340–1349. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.12.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garland CF, Comstock GW, Garland FC, Helsing KJ, Shaw EK, Gorham ED. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and colon cancer. Lancet. 1989;2(8673):1176–1178. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91789-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Rimm EB, et al. Prospective study of predictors of vitamin D status and cancer incidence and mortality in men. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(7):451–459. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garland CF, Garland FC, Gorham ED, et al. The role of vitamin D in cancer prevention. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(2):252–261. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.045260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin J, Manson JE, Lee IM, Cook NR, Buring JE, Zhang SM. Intakes of calcium and vitamin D and breast cancer risk in women. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(10):1050–1059. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.10.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilkinson RJ, Llewelyn M, Toossi Z, et al. Influence of vitamin D deficiency and vitamin D receptor polymorphisms on tuberculosis among Gujarati Asians in west London: a case-control study. Lancet. 2000;355(9204):618–621. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02301-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cannell JJ, Vieth R, Umhau JC, et al. Epidemic influenza and vitamin D. Epidemiol Infect. 2006;134(6):1129–1140. doi: 10.1017/S0950268806007175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laaksi I, Ruohola JP, Tuohimaa P, et al. An association of serum vitamin D concentrations <40 nmol/L with acute respiratory tract infection in young Finnish men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(3):714–717. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.3.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Camargo CA, Jr, Ingham T, Wickens K, et al. Cord blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and risk of childhood wheeze in New Zealand [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(suppl):A993. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lappe JM, Travers-Gustafson D, Davies KM, Recker RR, Heaney RP. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation reduces cancer risk: results of a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(6):1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.6.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Autier P, Gandini S. Vitamin D supplementation and total mortality: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(16):1730–1737. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Avenell A, Cook JA, Maclennan GS, Macpherson GC. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent infections. Age Ageing. 2007;36(5):574–577. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martineau AR, Wilkinson RJ, Wilkinson KA, et al. A single dose of vitamin D enhances immunity to mycobacteria. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(2):208–213. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200701-007OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine . Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium, Phosphorus, Magnesium, Vitamin D, and Fluoride. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1999. pp. 250–287. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scragg R, Jackson R, Holdaway IM, Lim T, Beaglehole R. Myocardial infarction is inversely associated with plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 levels: a community-based study. Int J Epidemiol. 1990;19(3):559–563. doi: 10.1093/ije/19.3.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scragg R, Sowers M, Bell C. Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, diabetes, and ethnicity in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(12):2813–2818. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.2813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Black PN, Scragg R. Relationship between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and pulmonary function in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Chest. 2005;128(6):3792–3798. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.3792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, Dietrich T, Dawson-Hughes B. Estimation of optimal serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D for multiple health outcomes [published corrections appear in Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(5): 1253 and Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(3):809] Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(1):18–28. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forman JP, Giovannucci E, Holmes MD, et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and risk of incident hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49(5):1063–1069. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.087288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorham ED, Garland CF, Garland FC, et al. Optimal vitamin D status for colorectal cancer prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(3):210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garland CF, Gorham ED, Mohr SB, et al. Vitamin D and prevention of breast cancer: pooled analysis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103(3–5):708–711. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(3):266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vieth R, Bischoff-Ferrari H, Boucher BJ, et al. The urgent need to recommend an intake of vitamin D that is effective. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(3):649–650. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.3.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holick MF, Chen TC. Vitamin D deficiency: a worldwide problem with health consequences. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(4):1080S–1086S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.4.1080S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holick MF. Resurrection of vitamin D deficiency and rickets. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(8):2062–2072. doi: 10.1172/JCI29449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scragg R, Camargo CA., Jr. Frequency of leisure time physical activity and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in the US population: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(6):577–586. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Looker AC, Dawson-Hughes B, Calvo MS, Gunter EW, Sahyoun NR. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status of adolescents and adults in two seasonal subpopulations from NHANES III. Bone. 2002;30(5):771–777. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00692-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zadshir A, Tareen N, Pan D, Norris K, Martins D. The prevalence of hypovitaminosis D among US adults. Ethn Dis. 2005;15((4)(suppl 5)):S5-97–S5-101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. US Dept of Health and Human Services; Hyattsville, MD: [Accessed June 26, 2008]. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs /about/major/nhanes/datalink.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 34.US Department of Health and Human Services . Healthy People 2010: With Understanding and Improving Health and Objectives for Improving Health: Section 3: Cancer. 2nd ed. US Dept of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: Nov, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuoka LY, Ide L, Wortsman J, MacLaughlin JA, Holick MF. Sunscreens suppress cutaneous vitamin D3 synthesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;64(6):1165–1168. doi: 10.1210/jcem-64-6-1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wortsman J, Matsuoka LY, Chen TC, Lu Z, Holick MF. Decreased bioavailability of vitamin D in obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(3):690–693. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.3.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. JAMA. 2006;295(13):1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Institute of Medicine . Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolf M, Betancourt J, Chang Y, et al. Impact of activated vitamin D and race on survival among hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(7):1379–1388. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007091002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barger-Lux MJ, Heaney RP, Dowell S, Chen TC, Holick MF. Vitamin D and its major metabolites. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8(3):222–230. doi: 10.1007/s001980050058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]