Abstract

The abnormally high cation permeability in red blood cells (RBCs) from patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) occupies a central role in pathogenesis. Sickle RBC properties are notably heterogeneous, however, thus limiting conventional flux techniques that necessarily average out the behaviour of millions of cells. Here we use the whole-cell patch configuration to characterise the permeability of single RBCs from patients with SCD in more detail. A non-specific cation conductance was reversibly induced upon deoxygenation and was permeable to both univalent (Na+, K+, Rb+) and also divalent (Ca2+, Mg2+) cations. It was sensitive to the tarantula spider toxin GsMTx-4. Mn2+ caused partial, reversible inhibition. The aromatic aldehyde o-vanillin also irreversibly inhibited the deoxygenation-induced conductance, partially at 1 mm and almost completely at 5 mm. Nifedipine, amiloride and ethylisopropylamiloride were ineffective. In oxygenated RBCs, the current was pH sensitive showing a marked increase as pH fell from 7.4 to 6, with no change apparent when pH was raised from 7.4 to 8. The effects of acidification and deoxygenation together were not additive. Many features of this deoxygenation-induced conductance (non-specificity for cations, permeability to Ca2+ and Mg2+, pH sensitivity, reversibility, partial inhibition by DIDS and Mn2+) are shared with the flux pathway sometimes referred to as Psickle. Sensitivity to GsMTx-4 indicates its possible identity as a stretch-activated channel. Sensitivity to o-vanillin implies that activation requires HbS polymerisation but since the conductance was observed in whole-cell patches, results suggest that bulk intracellular Hb is not involved; rather a membrane-bound subfraction is responsible for channel activation. The ability to record Psickle-like activity in single RBCs will facilitate further studies and eventual molecular identification of the pathway involved.

Key points

The high cation permeability in red blood cells (RBCs) from patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) is central to pathogenesis and includes a deoxygenation-induced pathway termed Psickle.

Here whole-cell patch clamp configuration was used to record from RBCs of SCD patients and showed a conductance reversibly induced upon deoxygenation, permeable to univalent (Na+, K+, Rb+) and divalent (Ca2+, Mg2+) cations, and sensitive to tarantula spider toxin GsMTx-4, Mn2+ and o-vanillin.

Divalent cation permeability is particularly important as entry of Ca2+ stimulates the Gardos channel whilst Mg2+ loss will stimulate KCl cotransport.

In oxygenated RBCs, the conductance was pH sensitive, increasing as pH fell from 7.4 to 6, but unaffected when pH was raised from 7.4 to 8.

Results show a conductance that shares many features with the Psickle flux pathway, and indicating its possible identity as a stretch-activated channel with activation requiring sickle cell haemoglobin (HbS) polymerisation.

Introduction

Unlike most mammalian cell types, human red blood cells (RBCs) do not respond to solute loss with a regulatory volume increase (RVI) (Ellory et al. 1985). Hence, decreased volume on shrinkage is largely irreversible, and RBCs in the circulation become smaller and denser with age (Hall & Ellory, 1986). This is critical for erythrocytes from patients with sickle cell disease (SCD), where decreased cell volume and hence increased haemoglobin concentration promotes HbS polymerization under deoxygenated conditions, leading eventually to irreversible sickling (Eaton & Hofrichter, 1987). In RBCs from SCD patients, two main routes for solute loss, represented by K+ and Cl− efflux, reduce cell volume (Joiner, 1993; Gibson & Ellory, 2002; Lew & Bookchin, 2005). One pathway is mediated via the K+–Cl− cotransporters (KCC, probably KCC3 and KCC1: Gamba, 2005) which are abnormally active in red cells from SCD patients (Brugnara et al. 1986; Crable et al. 2005). Another involves a non-selective ion and small solute permeability pathway, often termed Psickle, which acts as a direct efflux pathway for K+ loss (although balanced to a large extent by Na+ entry) but which also promotes Ca2+ entry and hence activation of the Gardos (Ca2+-activated K+ channel: Gardos, 1958; Hoffman et al. 2003) pathway (Joiner et al. 1988; Joiner, 1993; Lew et al. 1997). The consequence is rapid K+ loss with Cl− following via a separate conductive pathway. Psickle also promotes Mg2+ depletion (Ortiz et al. 1990; Willcocks et al. 2002), which also promotes KCl loss through elevated KCC activity, probably via inhibition of regulatory protein kinases (Gibson & Ellory, 2003). Subsequent intracellular acidification following KCl loss represents a positive feedback path which may have considerable importance (Lew & Bookchin, 2005).

Psickle remains ill-defined but is often referred to as a non-selective cation conductance activated by deoxygenation, HbS polymerisation and red cell shape change (Mohandas et al. 1986; Joiner, 1993). An obvious question that has prompted considerable discussion is its molecular identity. Psickle is not active in red cells from normal (HbAA) individuals. Since the aetiology of SCD is that of a simple single gene mutation, the Psickle pathway is probably derived from membrane components present in normal HbAA red cells, but which either develop or function abnormally when HbS is present. A variety of studies has used either conventional tracer fluxes or haemolysis (Joiner et al. 1988, 1993; Lew et al. 1997), and more recently patch clamp methodology (Browning et al. 2007; Dalibalta et al. 2010; Vandorpe et al. 2010), in attempts to elucidate the identity of Psickle. Speculations to link its identity with the Band 3 anion transporter (AE1), the Gardos channel, stretch-activated cation channels or Ca2+ channels have been made, principally based on inhibitor profiles (Gibson & Ellory, 2002; Bruce et al. 2005; Lew & Bookchin, 2005). In fact, to date, effective specific inhibitors are lacking, though partial Psickle inhibitors have been described (Joiner, 1990; Joiner et al. 2001; Browning et al. 2007).

The present work develops findings from previous patch clamp studies (Browning et al. 2007; Dalibalta et al. 2010; Vandorpe et al. 2010) with the aim of confirming and extending the ion specificity and inhibitor profile, and of defining the pH sensitivity, of the conductance measured in deoxygenated sickle cells. We show a significant Ca2+ transport via this pathway (in contrast with an earlier criticism), but conclude that Psickle is unlikely to involve a classical Ca2+ channel per se. Significant Mg2+ conductance is observed for the first time. Non-selective cation channel blockers, amiloride and ethylisopropylamiloride, were ineffective. A further association with HbS polymerisation is suggested by the irreversible inhibitory effects of the aromatic aldehyde o-vanillin (Zaugg et al. 1977; Abraham et al. 1991). The activation by low pH is not additive with deoxygenation, and indicates another stress to which HbS cells may be subjected physiologically.

Methods

Human red blood cells (RBCs)

HbSS and HbAA blood samples were obtained from volunteers with full ethical consent (NHS REC reference number 11/LO/0065). The method of handling the blood has been described in detail previously (Browning et al. 2007). In brief, the samples were collected into tubes containing EDTA as anticoagulant and were kept refrigerated until use. The cells used for experimental recordings were prepared by washing the blood three times by centrifugation (1000 g, 1 min) using Mops-buffered saline solution comprising (mm): NaCl 145, Mops 10 and glucose 5, pH 7.4. The buffy coat was removed and the washed cells were then diluted into the appropriate recording solution at approximately 0.01% haematocrit.

Electrophysiological recording and perfusion system

RBCs were placed in a recording chamber with a volume of approximately 2 ml, and whole-cell currents were recorded using the whole-cell configuration of the patch clamp technique at room temperature (22–24°C), using an Axopatch 200B patch clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA). Recording pipettes, made from borosilicate glass using an electrode puller (DMZ-Universal Puller, Zeitz-Instrumente GmbH, Germany), had resistances between 10 and 15 MΩ when filled with the pipette solution. Voltage commands were generated and currents were recorded with pCLAMP data acquisition software (Version 9.2. Axon Instruments). Current–voltage (I–V) relationships were obtained by applying a series of 300 ms test potentials from −100 mV to +100 mV in 10 mV increments, from a holding potential of 0 mV. Data for the construction of I–V curves were obtained by averaging the final 50 ms of the current. Data are presented without correcting for the background seal conductance. Full details have been described previously (Browning et al. 2007).

A ValveLink 8 (AutoMate Scientific, Inc.) perfusion system was used for drug delivery or changing of experimental conditions. The perfusion speed was adjusted to ∼5 ml min−1. Deoxygenation was achieved by bubbling the solution using 100% nitrogen for at least 20 min prior to switching on the perfusion. In order to maintain the perfusion chamber deoxygenated, a PDMI-2 perfusion chamber holding system (Harvard Apparatus) was used to deliver nitrogen above the chamber continually. The oxygen level in this system was measured with an ISO2 oxygen meter (World Precision Instrument) and was less than 1% compared with the atmospheric oxygen level of about 20%.

Experimental solutions and drugs

The normal extracellular solution contained (mm): NaCl 115; KCl 5; MgCl2 10; CaCl2 5; Hepes 10; glucose 10, pH 7.4. Unless otherwise stated, the pipette solution contained (mm): KCl 130; MgCl2 1; EGTA 1; Hepes 10.0; glucose 10; Mg-ATP 1.0, pH 7.4. To record Ca2+ conductance, a high-Ca2+ extracellular solution was used comprising (mm): CaCl2 82; MgCl2 10; Hepes 10, pH 7.4, with a pipette solution containing CaCl2 80; Hepes 5; Mg-ATP 1, pH 7.4. To record Mg2+ conductance, a high-Mg2+ extracellular solution was used comprising (mm): MgCl2 82; CaCl2 5; Hepes 10, pH 7.4, with a pipette solution containing MgCl2 80; Hepes 5; EGTA 1; Mg-ATP 1, pH 7.4. In the experiments described in Fig. 9, where extracellular pH was changed during the recording, the same Hepes-buffered saline was used (as above), with pH adjusted to that indicated. In these experiments, the low haematocrit together with absence of other pH disturbances meant that Hepes was adequate to hold the pH at the required value, but this was also checked during the experiment.

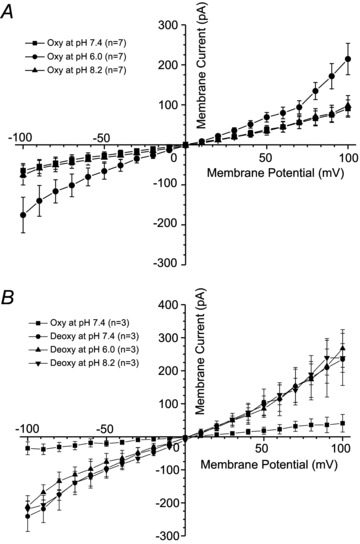

Figure 9. The effect of pH and oxygen tension on whole whole-cell currents recorded in red blood cells (RBCs) from patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Currents were measured in RBCs from homozygous (HbSS) SCD patients at holding potentials −100 to +100 mV, as described in the Methods. The main cations in pipette and extracellular solutions were K+ and Na+, respectively. Solutions were nominally Ca2+ free and any contaminant Ca2+ was removed by inclusion of EGTA (2 mm). A, in the same RBC, currents were recorded under oxygenated conditions (20% O2) sequentially at 3 different extracellular pHs: pH 7.4, 6 and 8.2 (n = 7). B, in the same RBC, currents were recorded first under oxygenated conditions (20% O2), pH 7.4, after which the cell was deoxygenated (O2 <1%), and measurements repeated sequentially at pH 7.4, 6.0 and 8.2 (n = 3).

Drugs/reagents used were: Grammastola spatulata mechanotoxin IV (GsMTx-4; Peptides International Inc., USA), streptomycin sulphate, gentamicin sulphate, o-vanillin, clotrimazole, amiloride, EIPA and GdCl3. All reagents were obtained from Sigma (Poole, Dorset, UK) unless otherwise stated.

Data analysis

The data are usually presented as means ± SEM for n experiments although representative traces from a single RBC are shown in Fig. 3B. The differences between control levels and the changes caused by alteration of experimental conditions were used as a measure of the outcome of the experiment. Data analysis was carried out using pClampfit software (Axon Instruments) and Origin software (Microcal software, Inc., Northampton, MA, USA). Drugs or deoxygenation were applied at least 3 min after the current records had stabilised. The results were tested using Student's t test.

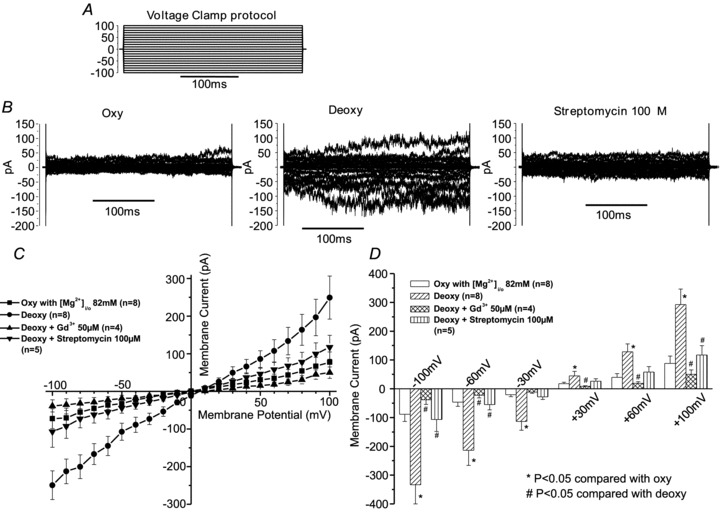

Figure 3. The effect of oxygen tension and inhibitors on whole-cell Mg2+ currents recorded in red blood cells (RBCs) from patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Currents were measured in RBCs from homozygous (HbSS) SCD patients at holding potentials −100 to +100 mV, as described in the Methods. In this case, the main cation in both pipette and extracellular solutions was Mg2+ (82 mm). The absence of K+ prevented any current passing through the Gardos channel. Measurements were carried out in the same RBC first under oxygenated conditions (20% O2), after which the perfusate was switched to deoxygenated saline (O2 <1%), in the absence and then presence of Gd3+ (50 μm) or streptomycin (100 μm). A, voltage clamp protocol; B, single representative experiment showing currents from a single RBC; C and D, means ± SEM for 4–8 RBCs.

Results

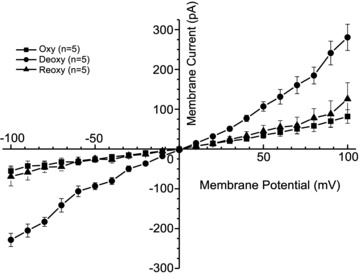

Reversible effects of oxygen tension

In our previous studies (Browning et al. 2007; Dalibalta et al. 2010), we have investigated deoxygenation-induced whole-cell current in HbS-containing RBCs in separate batches of oxygenated and deoxygenated cells. We showed that currents were markedly higher in deoxygenated conditions. In the first series of the present experiments, we confirmed the effect of deoxygenation using a perfusion system to enable current measurements in the same RBC in response to deoxygenation and then subsequent reoxygenation (Fig. 1). For a mean of 27 RBCs, the deoxygenation-induced current increased by 4.7-, 2.6-, 2.0- and 2.4-fold at holding potentials of −100, −80, +80 and +100 mV, respectively. In these experiments, the main cations in the bath and pipette were Na+ and K+, respectively. That deoxygenation increased univalent cation currents was confirmed, with values returning to low levels on reoxygenation (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The effect of oxygen tension on whole-cell currents recorded in red blood cells (RBCs) from patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Currents were measured in RBCs from homozygous (HbSS) SCD patients at holding potentials −100 to +100 mV, as described in the Methods. The main cations in pipette and extracellular solutions were K+ and Na+, respectively. Solutions were nominally Ca2+ free and any contaminant Ca2+ was removed by inclusion of EGTA (2 mm). Measurements were carried out in the same RBC first under oxygenated conditions (20% O2), then when deoxygenated (O2 <1%), after which the cell was subsequently reoxygenated (20%). Traces represent means ± SEM for 5 RBCs.

Ion selectivity of the deoxygenation-induced currents

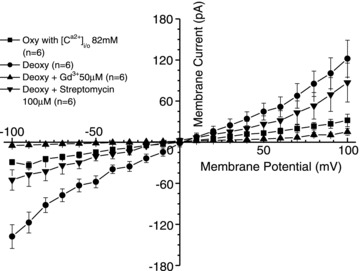

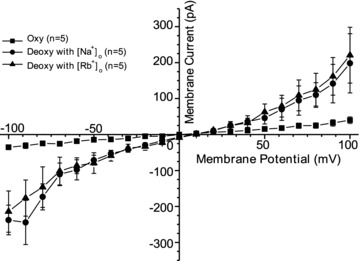

Transport of divalent cations through Psickle is considered to be particularly significant in the pathogenesis of SCD (Joiner, 1993; Lew & Bookchin, 2005). Deoxygenation-induced Ca2+ entry contributes to activation of the Gardos channel whilst Mg2+ loss would stimulate KCC, probably acting via altered activity of the regulatory protein kinases. In the next series of experiments, therefore, we looked at currents in symmetrical solutions high in either Ca2+ or Mg2+. Results are shown in Figs 2 and 3. In both cases, large inward and outward currents were observed with values again stimulated by deoxygenation. These were also reversible on reoxygenation. The dexoygenation-induced current increased by 4.7-, 3.8-, 3.7- and 3.8-fold for Ca2+ (n = 6), and 3.8-, 4.0-, 3.3- and 3.3-fold for Mg2+ (n = 10) at holding potentials of −100, −80, +80 and +100 mV, respectively. As for currents recorded with univalent cations, Gd3+ reduced currents to slightly less than values under oxygenated conditions in both Ca2+ and Mg2+ solutions (Figs 2 and 3). Streptomycin also inhibited but was more effective for Mg2+ than for Ca2+ (Figs 2 and 3). Membrane permeability for the major divalent cations therefore appears to behave similarly to that with univalent cations. Psickle is also permeable to smaller cations, such as Rb+, but not organic cations (like NMDG+) or anions (like Cl−) (Browning et al. 2007; Joiner, 1993). Figure 4 shows that with Rb+ as the main cation substantial deoxygenation-induced currents were also observed. Substitution of Cl− with gluconate, however, was without effect on the current, consistent with a deoxygenation-induced permeability to Cl− being unlikely (data not shown). Ion selectivity of the deoxygenation-induced conductance therefore appears similar to that of Psickle as a flux pathway.

Figure 2. The effect of oxygen tension and inhibitors on whole-cell Ca2+ currents recorded in red blood cells (RBCs) from patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Currents were measured in RBCs from homozygous (HbSS) SCD patients at holding potentials −100 to +100 mV, as described in the Methods. In this case, the main cation in both pipette and extracellular solutions was Ca2+ (82 mm). The absence of K+ prevented any current passing through the Gardos channel. Measurements were carried out in the same RBC first under oxygenated conditions (20% O2), after which the perfusate was switched to deoxygenated saline (O2 <1%), in the absence and then presence of Gd3+ (50 μm) or streptomycin (100 μm). Traces represent means ± SEM for 6 RBCs.

Figure 4. The effect of extracellular cation substitution on whole-cell currents recorded in red blood cells (RBCs) from patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Currents were measured in RBCs from homozygous (HbSS) SCD patients at holding potentials −100 to +100 mV, as described in the Methods. The main cation in the pipette was K+, with contaminant Ca2+ removed by inclusion of EGTA (2 mm). The initial extracellular cation was Na+. Measurements were carried out in the same RBC first under oxygenated conditions (20% O2), after which the cell was deoxygenated (O2 <1%). Na+ was then substituted with Rb+ whilst maintaining deoxygenated conditions. Traces represent means ± SEM for 5 RBCs.

Inhibitors of the deoxygenation-induced cation currents

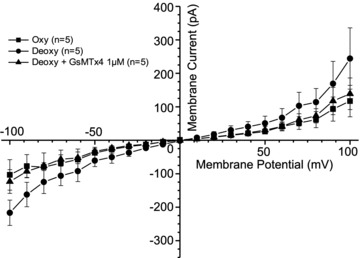

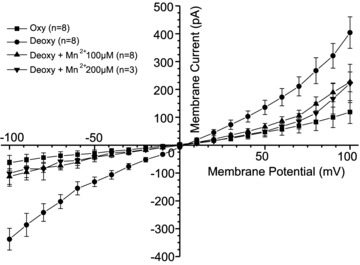

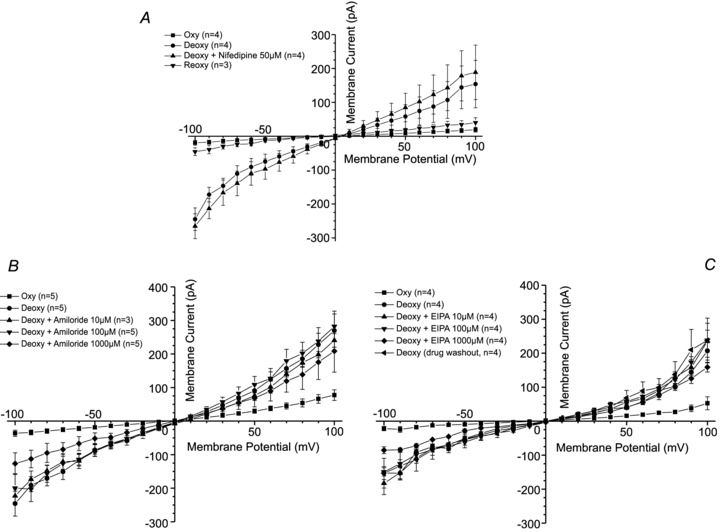

We have previously described whole-cell currents in HbS-containing RBCs which were partially inhibited by DIDS and Zn2+ (by about 25% and 40%, respectively), and sensitive to promiscuous stretch-activated channel blockers represented by streptomycin and Gd3+ (by about 50% and 90%, respectively) (Browning et al. 2007; Dalibalta et al. 2010). Here we extended our study to examine the effects of four different classes of inhibitors: to a more specific stretch-activated channel blocker, the tarantula spider toxin GsMTx-4 (which has been reported to inhibit currents in RBCs from sickle cell patients –Vandorpe et al. 2010); Mn2+ (which amongst inhibitory divalent cations has the maximum effect against Psickle–Joiner et al. 1995); nifedipine (a classic Ca2+ channel blocker –Ellory et al. 1992b) and amiloride and its analogue ethylisopropylamiloride (EIPA) (inhibitors of voltage-activated non-selective cation channels and also the Na+(K+)/H+ exchanger in RBCs –Kaestner & Bernhardt, 2002; Lang et al. 2003; Weiss et al. 2004). In these experiments, the main cations in the pipette and bath were again K+ and Na+, respectively. GsMTx-4 largely abolished the deoxygenation-induced conductance (Fig. 5), confirming the findings of Vandorpe et al. (2010). Mn2+ also substantially inhibited both inward and outward currents (Fig. 6). Effects were apparent at 100 μm. They did not show increased inhibition on doubling the concentration but were reversible on washing out Mn2+ (Fig. 6, and data not shown). As Ca2+ is a permeant of the deoxygenation-induced pathway, in the final experiment of this series, the effect of the classic Ca2+ channel blocker nifedipine was also tested but no inhibition was observed (Fig. 7A). Inhibitors of the non-selective cation conductance of RBCs activated by depolarisation (and also of Na+(K+)/H+ exchange), amiloride and EIPA, also had no effect at moderate concentrations (100 μm and lower) although a modest reduction was observed at 1 mm (Fig. 7B and C).

Figure 5. The effect of tarantula spider toxin (GsMTx-4) on deoxygenation-induced whole-cell currents recorded in red blood cells (RBCs) from patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Currents were measured in RBCs from homozygous (HbSS) SCD patients at holding potentials −100 to +100 mV, as described in the Methods. The main cations in pipette and extracellular solutions were K+ and Na+, respectively. Solutions were nominally Ca2+ free and any contaminant Ca2+ was removed by inclusion of EGTA (2 mm). Measurements were carried out in the same RBC first under oxygenated conditions (20% O2), after which the cell was deoxygenated (O2 <1%), first in the absence and then the presence of GsMTx-4 (1 μm). Traces represent means ± SEM for 5 RBCs.

Figure 6. The effect of Mn2+ on deoxygenation-induced whole-cell currents recorded in red blood cells (RBCs) from patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Currents were measured in RBCs from homozygous (HbSS) SCD patients at holding potentials −100 to +100 mV, as described in the Methods. The main cations in pipette and extracellular solutions were K+ and Na+, respectively. Solutions were nominally Ca2+ free and any contaminant Ca2+ was removed by inclusion of EGTA (2 mm). Measurements were carried out in the same RBC first under oxygenated conditions (20% O2), after which the cell was deoxygenated (O2 <1%), first in the absence and then the presence of Mn2+ (100 or 200 μm). Traces represent means ± SEM for 3–8 RBCs.

Figure 7. The effect of cation channel blockers on deoxygenation-induced whole-cell currents recorded in red blood cells (RBCs) from patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Currents were measured in RBCs from homozygous (HbSS) SCD patients at holding potentials −100 to +100 mV, as described in the Methods. The main cations in pipette and extracellular solutions were K+ and Na+, respectively. Solutions were nominally Ca2+ free and any contaminant Ca2+ was removed by inclusion of EGTA (2 mm). Measurements were carried out in the same RBC first under oxygenated conditions (20% O2), after which the cell was deoxygenated (O2 <1%), first in the absence and then the presence of inhibitors: A, nifedipine (50 μm), n = 4; B, amiloride (10, 100 and 1000 μm), n = 3–5; C, ethylisopropylamiloride (EIPA; 10, 100 and 1000 μm), n = 4. All traces represent means ± SEM for 3–5 RBCs.

The effect of aromatic aldehydes

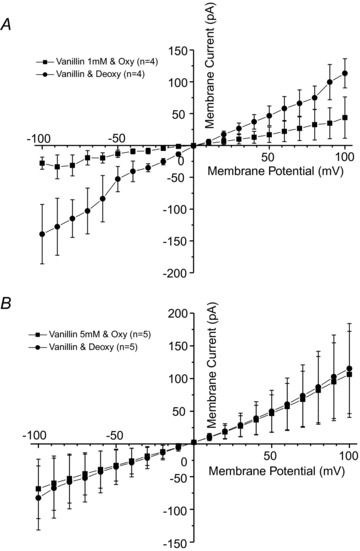

Psickle is probably activated by HbS polymerisation. Aromatic aldehydes form Schiff bases with haemoglobin and were designed as potential anti-sickling agents as they reduce the ability of HbS to polymerise on deoxygenation (Zaugg et al. 1977; Abraham et al. 1991). One of these is o-vanillin and its effects were therefore tested on the deoxygenation-induced conductance (Fig. 8). Pre-treatment of RBCs with 1 mm had little effect on the deoxygenation-induced currents (Fig. 8A). By contrast, 5 mmo-vanillin largely removed any increase in currents on deoxygenation (Fig. 8B). At this high concentration, it was possible the o-vanillin was partitioning into the RBC membrane and producing a non-specific effect on membrane channels. This was tested by examining its effect on Gardos channel activity in the presence of [Ca2+]i to activate the Gardos channel. No inhibition was observed on addition of 5 mmo-vanillin whilst, by contrast, clotrimazole, a known inhibitor of Ca2+-activated K+ channels (Alvarez et al. 1992; Ellory et al. 1992a; Brugnara et al. 1993) abolished the currents (data not shown).

Figure 8. The effect of o-vanillin on deoxygenation-induced whole-cell currents recorded in red blood cells (RBCs) from patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Currents were measured in RBCs from homozygous (HbSS) SCD patients at holding potentials −100 to +100 mV, as described in the Methods. The main cations in pipette and extracellular solutions were K+ and Na+, respectively. Solutions were nominally Ca2+ free and any contaminant Ca2+ was removed by inclusion of EGTA (2 mm). RBCs were pre-incubated for 30 min in the absence or presence if o-vanillin after which currents were recorded first in oxygenated cells (20% O2) and then under deoxygenated conditions (O2 <1%): A, 1 mm and (B) 5 mmo-vanillin. Traces represent means ± SEM for 4 or 5 RBCs.

Effect of pH on deoxygenation-induced currents

Psickle is described as pH sensitive (Joiner et al. 1993). We therefore went on to investigate the effect of pH on whole-cell currents with the main cations in the pipette and bath again being K+ and Na+, respectively. In these experiments, currents were first measured in oxygenated RBCs at pH 7.4. They were then taken to pH 6.0 when currents increased to a similar magnitude as that seen during deoxygenation (Fig. 9A). The stimulatory effect of low pH was reversible on restoring pH to 7.4. Higher pH, 8.2, had no effect. Finally, under deoxygenated conditions, altering pH had no further stimulatory effect (Fig. 9B).

Discussion

The present findings further characterise significant electrophysiological features of RBCs from SCD patients. Results demonstrate a reversible increase in whole-cell cation currents upon deoxygenation. The deoxygenation-induced cation conductance demonstrated considerable permeability to both Ca2+ and Mg2+, and also Rb+, but not to Cl− or NMDG+. It was insensitive to the classical Ca2+ channel blocker nifedipine as well as to the non-selective RBC cation channel blockers amiloride and ethylisopropylamiloride (EIPA), but was fully inhibited by the mechanotoxin GsMTx-4, consistent with its possible mediation via stretch-activated channels. It was substantially inhibited by both the partial Psickle inhibitor Mn2+ and by the anti-sickling reagent o-vanillin. Finally, low pH mimicked the effect of deoxygenation, but at low pH the conductance became oxygen insensitive.

Under our standard conditions using the whole-cell patch clamp configuration with asymmetrical K+-rich pipette solution and Na+-rich bath (Browning et al. 2007), it was routinely possible to obtain high-resistance seals (with a success rate of about 15%). Currents in normal (HbAA) RBCs were small, as were those recorded in oxygenated HbS cells, albeit slightly larger in the latter case (Browning et al. 2007). On deoxygenation, currents in RBCs from SCD patients were increased by about 3- to 5-fold. Using a flow perfusion apparatus, we show also here that currents were fully reversible on reoxygenation. Similar results were also obtained when the major cation current carriers were Ca2+ and Mg2+, again with a similar-fold increase on deoxygenation, showing that the pathway was permeable to these physiologically important divalent cations. A permeability with these characteristics would have the potential to raise intracellular Ca2+ concentration with concomitant stimulation of the Gardos channel (Rhoda et al. 1990; Etzion et al. 1993; Lew et al. 2002), and lower that of Mg2+ with subsequent elevation of KCC activity (Ortiz et al. 1990; Gibson & Ellory, 2002; Willcocks et al. 2002), both important features of deoxygenated RBCs from SCD patients.

Possible permeability of the conductance to anions, particularly the main univalent anion Cl−, is an important issue. Previously we presented evidence that currents in univalent cation solutions (Na+ or K+) were unlikely to be mediated by Cl− (Browning et al. 2007). In the present work, we show that currents were also recorded in Mg2+ gluconate solutions and that they were also stimulated about 3-fold by deoxygenation. These observations make a significant Cl− conductance unlikely.

An obvious next question is the identity of Psickle in terms of a specific ion channel(s). RBCs are thought to show a number of different cation channels which may represent potential candidates (Bennekou & Christophersen, 2003; Kaestner, 2011). Resolving the identity of Psickle, however, is hindered by lack of true specificity of most inhibitors. Here we demonstrate that nifedipine was ineffective at inhibiting the deoxygenation-induced current, which implies that it is not a true Ca2+ channel. Inhibitors of the non-selective RBC cation channel activated by depolarisation were also without effect. In addition, whilst some divalent cations (Ca2+, Mg2+) permeate, others (notably Zn2+ and Mn2+) inhibit, whilst low concentrations of Cd2+ and Co2+ were without effect (see Results and Browning et al. 2007). We also show that several promiscuous stretch-activated channel blockers were partially effective in reducing the deoxygenation-induced pathways for both monovalent (Dalibalta et al. 2010) and divalent cations, including Gd3+ and streptomycin. As described for cell-attached patches (Vandorpe et al. 2010), tarantula spider toxin GsMTx-4 also substantially inhibited the deoxygenation-induced whole-cell cation currents. These findings suggest a possible identity for Psickle as a stretch-activated channel. In this context, it is interesting that several members of the TRPC family are found in erythroid cells (Hirshler-Laszkiewicz et al. 2009). Their expression is increased by erythropoietin (Hirshler-Laszkiewicz et al. 2009), which would be elevated in chronic anaemia like that observed in SCD. Some of these channels are sensitive to GsMTx-4 (Bowman et al. 2007).

As noted previously, in our whole-cell recordings, DIDS and dipyridamole inhibit partially (Browning et al. 2007), as described for the Psickle flux pathway. This is in contrast to their effect on deoxygenation-induced Na+ currents in single channel experiments with sickle cells (Vandorpe et al. 2010), where inhibition is complete. These observations may be reconciled if these deoxygenation-induced permeabilities are mediated by more than one pathway, or that a single pathway may exist with different activation states. This possibility has been discussed with respect to RBC anion channels, of variable ion selectivity and activity, perhaps corresponding to permeability through peripheral benzodiazepine receptors (Bouyer et al. 2011).

In our whole-cell experiments, the intracellular contents will exchange with pipette solution so that soluble components, including Hb, would no longer be present. These findings imply therefore that the regulatory apparatus remains functional and membrane-attached, which is relevant to its mechanism of activation. Microscopic visualisation of the RBCs showed that on patching, cells assumed a spherical morphology and this was not altered on deoxygenation; thus, it is unlikely that the higher currents on deoxygenation were artefactual resulting from membrane distortion mediating a reduction in seal resistance, as suggested by Vandorpe et al. (2010). Results also showed that o-vanillin, an aromatic benzaldehyde that forms Schiff bases with haemoglobin (Zaugg et al. 1977; Abraham et al. 1991), substantially reduced the deoxygenation-induced currents. This reagent increases oxygen affinity, but not sufficiently to prevent deoxygenation of Hb. It also reduces the ability of HbS to polymerise and we hypothesise that it is this which reduces conductance. Interestingly, inhibition with o-vanillin was also observed if currents were first increased by deoxygenation prior to addition of the aldehyde. The inability of o-vanillin to affect currents through clotrimazole-sensitive Gardos channels suggests that its effects are specific to particular conductance pathways. Taken together, we suggest that these findings may be explained by a subfraction of HbS that remains membrane-bound after breaking the patch, and assuming the whole-cell configuration, and that remains able to affect membrane conductance. A role for membrane-bound Hb has also been proposed for the abnormal KCC activity in intact SCD RBCs and which is retained in pink ghosts (Drew et al. 2004).

We went on to study pH dependence, a feature of Psickle with potential pathophysiological significance (Joiner et al. 1993). We found that deoxygenation-induced whole-cell currents were markedly stimulated as pH was lowered from 7.4 to 6, but were largely unaffected by a rise in pH from 7.4 to 8. This pH dependence may be particularly relevant to RBCs circulating through areas such as hypoxic muscle beds where the blood is also likely to be acidotic. A number of differences are found comparing the pH dependence of Psickle with the currents described here. In the case of Psickle, the deoxygenation-induced cation flux has a bell-shaped response to altered pH (Joiner et al. 1993), with fluxes maximal at about pH 6. Flux studies require prolonged deoxygenation (60 min) whilst, in addition, altering pH may affect membrane potential. Any depolarisation would reduce cation influx. It is also possible that prolonged acidification and deoxygenation may alter the polymerisation of HbS, cell shape and cell volume. On the other hand, the whole-cell configuration may lead to the loss of the inhibitory regulatory apparatus responsible for the reduction in influx at lower pH values observed in flux studies. Interestingly, in white ghosts to which HbS is re-added, pH sensitivity is restored but the bell-shaped response is also lost (Vitoux et al. 1999). These possibilities are under investigation.

In conclusion, the experiments described here present further evidence that the whole-cell patch clamp recordings show the electrical manifestation of Psickle, consistent with mediation by stretch-activated channels. Permeability to Ca2+ and Mg2+ would increase dehydration of RBCs from SCD patients by promoting activation of the Gardos channels and also stimulation of KCC.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Wellcome Trust and Medical Research Council for financial support.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- HbAA

red cells from normal individuals

- HbS

sickle cell haemoglobin

- RBC

red blood cell

- RVI

regulatory volume increase

- SCD

sickle cell disease

Author contributions

Y-LM carried out the experiments and analysed the data; DCR, JSG and JCE designed the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version for publication. Experiments were carried out in Oxford.

References

- Abraham DJ, Mehanna AS, Wireko FC, Whitney J, Thomas RP, Orringer EP. Vanillin, a potential agent for the treatment of sickle cell anemia. Blood. 1991;77:1334–1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez J, Montero M, Garcia-Sanchez J. High affinity inhibition of Ca2+-dependent K+ channels by cytochrome P-450 inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:11789–11793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennekou P, Christophersen P. Ion channels. In: Bernhardt I, Ellory JC, editors. Red Cell Membrane in Health and Disease. Berlin: Springer; 2003. pp. 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Bouyer G, Cueff A, Egée S, Kmiecik J, Maksimova Y, Glogowska E, Gallagher PG, Thomas SL. Erythrocyte peripheral benzodiazepine receptor/voltage-dependent anion channels are upregulated by Plasmodium falciparum. Blood. 2011;118:2305–2312. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-329300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman CL, Gottlieb PA, Suchyna TM, Murphy YK, Sachs F. Mechanosensitive ion channels and the peptide inhibitor GsMTx-4: history, properties, mechanisms and pharmacology. Toxicon. 2007;49:249–270. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning JA, Staines HM, Robinson HC, Powell T, Ellory JC, Gibson JS. The effect of deoxygenation on whole-cell conductance of red blood cells from healthy individuals and patients with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2007;109:2622–2629. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-001404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce LJ, Robinson HC, Guizouarn H, Borgese F, Harrison P, King MJ, et al. Monovalent cation leaks in human red cells caused by single amino-acid substitutions in the transport domain of the band 3 chloride-bicarbonate exchanger, AE1. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1258–1263. doi: 10.1038/ng1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugnara C, Bunn HF, Tosteson DC. Regulation of erythrocyte cation and water content in sickle cell anemia. Science. 1986;232:388–390. doi: 10.1126/science.3961486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugnara C, de Franceschi L, Alper SL. Inhibition of Ca2+-dependent K+ transport and cell dehydration in sickle erythrocytes by clotrimazole and other imidazole derivatives. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:520–526. doi: 10.1172/JCI116597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crable SC, Hammond SM, Papes R, Rettig RK, Zhou G-P, Gallagher PG, Joiner CH, Anderson KP. Multiple isoforms of the KCl cotransporter are expressed in sickle and normal erythroid cells. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:624–631. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalibalta S, Ellory JC, Browning JA, Wilkins RJ, Rees DC, Gibson JS. Novel permeability characteristics of red blood cells from sickle cell patients. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2010;45:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew C, Ball V, Robinson H, Ellory JC, Gibson JS. Oxygen sensitivity of red cell membrane transporters revisited. Bioelectrochemistry. 2004;62:153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton WA, Hofrichter J. Hemoglobin S gelation and sickle cell disease. Blood. 1987;70:1245–1266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellory JC, Culliford S, Stone PCW, Stuart J. Clotrimazole, a potent Gardos channel inhibitor, protects sickle cells from K loss and dehydration. J Physiol. 1992a;458:159P. [Google Scholar]

- Ellory JC, Hall AC, Stewart GW. Volume-sensitive cation fluxes in mammalian red cells. Mol Physiol. 1985;8:235–246. [Google Scholar]

- Ellory JC, Kirk K, Culliford SJ, Nash GB, Stuart J. Nitrendipine is a potent inhibitor of the Ca2+-activated K+ channel of human erythrocytes. FEBS Lett. 1992b;296:219–221. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80383-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etzion Z, Tiffert T, Bookchin RM, Lew VL. Effects of deoxygenation on active and passive Ca2+ transport and on the cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels of sickle cell anemia red cells. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2489–2498. doi: 10.1172/JCI116857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamba G. Molecular physiology and pathophysiology of electroneutral cation-chloride cotransporters. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:423–493. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardos G. The function of calcium and potassium permeability of human erythrocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1958;30:653–654. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(58)90124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson JS, Ellory JC. Membrane transport in sickle cell disease. Blood Cell Mol Dis. 2002;28:1–12. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2002.0515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson JS, Ellory JC. K+-Cl– cotransport in vertebrate red cells. In: Bernhardt I, Ellory JC, editors. Red Cell Membrane Transport in Health and Disease. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 2003. pp. 197–220. [Google Scholar]

- Hall AC, Ellory JC. Evidence for the presence of volume-sensitive KCl transport in ‘young’ human red cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;858:317–320. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(86)90338-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshler-Laszkiewicz I, Tong Q, Conrad K, Flint WW, Barber AJ, Barber DL, Cheung JT, Miller BA. TRPC3 activation by erythropoietin is modulated by TRPC6. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4567–4581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804734200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman JF, Joiner W, Nehrke K, Potapova O, Foye K, Wickrema A. The hSK4 (KCNN4) isoform is the Ca2+-activated K+ channel (Gardos channel) in human red blood cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7366–7371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232342100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner CH. Deoxygenation-induced cation fluxes in sickle cells: II. Inhibition by stilbene disulfonates. Blood. 1990;76:212–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner CH. Cation transport and volume regulation in sickle red blood cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1993;264:C251–C270. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.2.C251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner CH, Dew A, Ge DL. Deoxygenation-induced fluxes in sickle cells. I. Relationship between net potassium efflux and net sodium influx. Blood Cells. 1988;13:339–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner CH, Jiang M, Claussen WJ, Roszell NJ, Yasin Z, Franco RS. Dipyridamole inhibits sickling-induced cation fluxes in sickle red blood cells. Blood. 2001;97:3976–3983. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.12.3976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner CH, Jiang M, Franco RS. Deoxygenation-induced cation fluxes in sickle cells IV. Modulation by external calcium. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1995;269:C403–C409. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.2.C403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner CH, Morris CL, Cooper ES. Deoxygenation-induced cation fluxes in sickle cells. III. Cation selectivity and response to pH and membrane potential. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1993;264:C734–C744. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.3.C734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaestner L. Cation channels in erythrocytes – historical and future persepective. Open Biol. 2011;4:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kaestner L, Bernhardt I. Ion channels in the human red blood cell membrane: their further investigation and physiological relevance. Bioelectrochemistry. 2002;55:71–74. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5394(01)00164-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang KS, Myssina S, Tanneur V, Wieder T, Huber SM, Lang F, Duranton C. Inhibition of erythrocyte cation channels and apoptosis by ethylisopropylamiloride. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2003;367:391–396. doi: 10.1007/s00210-003-0701-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew VL, Bookchin RM. Ion transport pathology in the mechanism of sickle cell dehydration. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:179–200. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00052.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew VL, Etzion Z, Bookchin RM. Dehydration response of sickle cells to sickling-induced Ca2+ permeabilization. Blood. 2002;99:2578–2585. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.7.2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew VL, Ortiz OE, Bookchin RM. Stochastic nature and red cell population distribution of the sickling-induced Ca2+ permeability. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2727–2735. doi: 10.1172/JCI119462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohandas N, Rossi ME, Clark MR. Association between morphologic distortion of sickle cells and deoxygenation-induced cation permeability increases. Blood. 1986;68:450–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz OE, Lew VL, Bookchin RM. Deoxygenation permeabilizes sickle cell anaemia red cells to magnesium and reverses its gradient in the dense cells. J Physiol. 1990;427:211–226. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoda MD, Apovo M, Beuzard Y, Giraud F. Ca2+ permeability in deoxygenated sickle cells. Blood. 1990;75:2453–2458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandorpe DH, Xu C, Shmukler BE, Otterbein LE, Trudel M, Sachs F, Gottlieb PA, Brugnara C, Alper SL. Hypoxia activates a Ca2+-permeable cation conductance sensitive to carbon monoxide and to GsMTx-4 in human and mouse sickle erythrocytes. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitoux D, Beuzard Y, Brugnara C. The effect of hemoglobin A and S on the volume- and pH-dependence of K-Cl cotransport in human erythrocyte ghosts. J Membr Biol. 1999;167:233–240. doi: 10.1007/s002329900487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss E, Lang HJ, Bernhardt I. Inhibitors of the K+(Na+)/H+ exchanger of human red blood cells. Bioelectrochemistry. 2004;62:135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willcocks JP, Mulquiney PJ, Ellory JC, Veech RL, Radda GK, Clarke K. Simultaneous determination of low free Mg2+ and pH in human sickle cells using 31P NMR spectroscopy. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49911–49920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207551200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaugg RH, Walder JA, Klotz IM. Schiff base adducts of hemoglobin. Modifications that inhibit erythrocyte sickling. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:8542–8548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]