The segmental pattern of cardiac sympathetic denervation involves the proximal lateral left ventricular wall most severely, with relative sparing of the anterior and proximal septal walls; this suggests a characteristic pattern of neuronal degeneration in idiopathic Parkinson disease.

Abstract

Purpose:

To determine whether cardiac sympathetic denervation in idiopathic Parkinson disease (IPD) affects the left ventricle in a distinct regional pattern versus a more global pattern with use of carbon 11 (11C) meta-hydroxyephedrine (HED) positron emission tomography (PET).

Materials and Methods:

This prospective study was approved by the institutional review board and was compliant with HIPAA. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Cardiac PET was performed with 11C HED in 27 patients with IPD (20 men and seven women aged 50–74 years; mean age, 62 years ± 6 [standard deviation]). 11C HED retention indexes (RIs), which reflect nerve density and integrity, were determined. RIs for 33 healthy control subjects (15 men and 18 women aged 20–78 years; mean age, 47 years ± 17) were used as a control database. Patients with IPD were compared with control subjects by using z score analysis. Global and segmental measurements of sympathetic denervation were expressed as percentage extent, z score severity, and severity-extent product (SEP). Group comparisons were performed with the Student t test.

Results:

The mean 11C HED RI was 0.086 mL of blood per minuteper milliliter tissue ± 0.015 for control subjects and 0.043 mL of blood per minute per milliliter tissue ± 0.016 for patients with IPD (P < 0001). When compared with normative data from the control database, profound cardiac denervation (global extent >50%) was seen in most patients (19 of 27 patients, 70%). Four patients had normal 11C HED studies and four had mild denervation (global extent <25%). The mean global denervation extent was 62% ± 38, the mean severity z score was -2.7 ± 1.2, and the mean SEP was −202 ± 131 (range, −358 to 0). Segmental analysis revealed relative sparing of anterior and proximal septal segments (mean extent, 48%–51%; mean severity z score, −2.47 to −2.0; mean SEP, −167 to −139), with lateral and proximal inferior segments more severely affected (mean extent, 68%–73%; mean severity z score, -2.8 to -2.62; mean SEP, -271 to -230). Patients with normal findings or preserved denervation did not significantly differ in mean age (t = 1.09) or disease duration (t = 0.44) compared to patients with severe sympathetic denervation.

Conclusion:

Cardiac sympathetic denervation in IPD is extensive, with a segmental pattern that involves the proximal lateral left ventricular wall most severely, with relative sparing of the anterior and proximal septal walls.

© RSNA, 2012

Supplemental material: http://radiology.rsna.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1148/radiol.12112723/-/DC1

Introduction

Idiopathic Parkinson disease (IPD) is associated with multiple autonomic comorbidities, including cardiac postganglionic, presynaptic sympathetic denervation (1). Previous studies of IPD with iodine 123 (123I) metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG), a false neurotransmitter with affinity for the presynaptic norepinephrine transporter of postganglionic sympathetic neurons, have demonstrated extensive reductions in cardiac 123I MIBG uptake indicative of cardiac sympathetic neuronal loss (2–22). The pathobiologic mechanism appears to be neurodegenerative, associated with α-synuclein accumulation in the autonomic cardiac plexus and distal axons (6,13,23–25).

Cardiac scintigraphy with 123I MIBG has been proposed as a diagnostic test with which to differentiate IPD with postganglionic autonomic dysfunction from other Parkinsonian syndromes such as multiple system atrophy with central and preganglionic sympathethic dysfunction (3,4,15,18,20). However, much of the sequence and process of cardiac sympathetic denervation in IPD remains poorly understood. Most studies using 123I MIBG have relied on heart-to-mediastinal ratios derived from early and delayed planar imaging. Cardiac sympathetic imaging with carbon 11 (11C) meta-hydroxyephedrine (HED) positron emission tomography (PET) has been reported in small numbers of patients with IPD (26,27). Cardiac PET has advantages of increased sensitivity and more accurate measurements of tissue radioactivity concentrations as compared with planar single-photon scintigraphy. 11C HED PET provides quantitative measurements of cardiac radiotracer retention, which reflects sympathetic nerve density, enabling global and segmental analysis of cardiac sympathetic denervation (1,28–30).

The purpose of the current study was to determine whether cardiac sympathetic denervation in IPD affects the left ventricle in a distinct regional pattern versus a more global pattern with use of 11C HED PET.

Materials and Methods

This study was not funded by industrial or commercial sources nor did it evaluate products for commercial purposes.

Study Population

The institutional review board of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, approved this investigation of patients with IPD and healthy control subjects. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. This prospective study was compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT01565473). We studied 27 patients with mild to moderate IPD (20 men and seven women aged 50–74 years; mean age ± standard deviation, 62 years ± 6). The diagnosis of IPD was established by means of published research criteria (31) on the basis of clinical neurologic examination (conducted by N.I.B., a neurologist with 20 years of experience) and confirmed by the presence of nigrostriatal dopaminergic denervation at dihydrotetrabenazine (DTBZ) vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 (VMAT2) PET based on putaminal dopaminergic losses greater than caudate nucleus that are often asymmetric (32). Each DTBZ scan was reviewed and confirmed to be consistent with IPD by PET neuroimaging experts (N.I.B., K.A.F., S.G.) at monthly consensus meetings.

Cardiac sympathetic denervation has been reported to occur as a result of a range of cardiac diseases, including diabetic cardiac autonomic neuropathy (33), after myocardial infarction, owing to congestive cardiac failure, and in cardiac transplant recipients (28). Therefore, patients with IPD were screened to exclude those with a history of cardiac disease or diabetes as well as those with abnormal Q waves at echocardiography. Nine patients with IPD were taking a combination of a dopamine agonist and carbidopa-levodopa, 14 patients were taking carbidopa-levodopa alone, one patient was taking a dopamine agonist alone, and three patients were not taking dopaminergic drugs. Patients taking tricyclic antidepressants, bupropion, calcium channel blockers, or β-blockers were not eligible for the study because these drugs may interfere with HED metabolism.

Radiochemistry

11C HED was prepared by 11C methylation of (−)-metaraminol as the free base and purified by means of high-performance liquid chromatography (34). This procedure provided 11C HED at specific activities of 18.5–55.5 TBq/mmol and radiochemical purities of greater than 98%.

11C HED PET Cardiac Imaging

With the patient lying comfortably in the PET scanner, a mean of 740 MBq ± 74 of 11C HED was injected intravenously and a dynamic sequence of cardiac scans was acquired over 40 minutes (framing rates = 12 × 10 seconds, 2 × 30 seconds, 2 × 60 seconds, 2 × 150 seconds, 2 × 300 seconds, and 2 × 600 seconds). A low-dose (74 MBq) nitrogen 13 ammonia cardiac localizer scan was obtained before administration of HED to position the heart in the center of the scanner field of view. All scans were obtained with an ECAT Exact HR+ PET scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Hoffman Estates, Ill), which has an intrinsic resolution of approximately 4.6 mm full width at half maximum. Sixty-three planes with a 2.425-mm center-to-center separation were imaged simultaneously. Attenuation correction using three germanium 68 line sources was applied to the measured transmission scan data, which were then segmented and reprojected into sinogram space. The resolution of the reconstructed images was approximately 8–9 mm at full width at half maximum based on the PET camera resolution and the selected matrix size. The cardiac images were resectioned into short-axis images for further quantitative analysis as previously described (35). A region of interest was placed over the left ventricular chamber in a short-axis section near the base of the heart (performed by D.M.R., a physicist with 20 years of experience), and a time-activity curve for total activity in blood was generated. Next, the left ventricular wall in each of the eight short-axis sections from the apex to the base was automatically subdivided into 60 angular sectors to generate a total of 480 sectors. The apical sections had at least four pixels per sector, whereas the basal section had at most 14 pixels per sector. The time-activity curve for tissue 11C HED concentration was determined for each sector. As a semiquantitative measure of nerve density and neuronal integrity, tissue 11C HED concentrations in the final image frame (30–40 minutes after injection) were normalized by dividing them by the integral of the blood time-activity curve over the 40-minute scan, as has been previously described (30). This procedure provided a 11C HED retention index (RI, in milliliters of blood per minute per milliliter of tissue) for each myocardial region. The RI reflects the ability of the sympathetic neurons to take up and store norepinephrine.

Healthy control subjects who did not have a history of cardiac or neurologic disease, diabetes mellitus, or other chronic medical conditions were recruited for this study. None of the control subjects were taking any medications that could have an effect on cardiac sympathetic neurons. The RIs for 33 healthy control subjects (15 men and 18 women aged 20–78 years; mean age, 47 years ± 17) were used to define a normal HED retention database in which the means and standard deviations for each myocardial sector were calculated. Measured RI data for each patient with IPD were compared with the healthy control database by means of z score analysis. For this analysis, a z score was calculated for each sector in a patient’s polar map, as follows: zi = (μi − qi)/σI, where qi is the patient’s RI for the ith sector of the polar map, μi the healthy population mean RI for that sector, and si the corresponding across-subject standard deviation of the healthy population for that sector. Left ventricular sectors with z scores of less than 2.5 (ie, their 11C HED RI values were more than 2.5 standard deviations below the healthy population mean) were considered to have abnormal 11C HED retention. An age-adjustment factor was applied to the HED RI values of the patients with IPD, normalizing to an age of 50 years. The control group had a very modest decline of the HED RI with age (1.3% decline per decade). The effect of age adjustment was considered minimal because the largest age correction performed in any one sector’s RI was an increase of 3% in one of the oldest patients with IPD.

We calculated the fraction of 480 sectors in each patient’s polar map that was abnormal as a measure of the extent of abnormal 11C HED retention in the left ventricle. Regional extent measures were generated for the left ventricle on the basis of perfusion territories of the three main coronary arteries: the left circumflex, left anterior descending, and right coronary arteries. In addition, the basal-to-apical gradient of sympathetic innervation was assessed with a nine-segment model on the polar map as previously described (30). Global, regional, and segmental measurements of abnormal cardiac sympathetic denervation were expressed as percentage extent, z score severity, and severity-extent product (SEP), which was obtained by multiplying the percentage extent and the z score severity integers. The SEP measurement combines percentage extent and severity of sympathetic denervation into a single product in a manner akin to the summed stress score used in routine myocardial perfusion imaging.

11C DTBZ PET Neuroimaging

All subjects with IPD also underwent brain magnetic resonance (MR) imaging and (+)-11C DTBZ VMAT2 PET for confirmation of nigrostriatal dopaminergic denervation consistent with Parkinson disease diagnosis. DTBZ PET was performed in three-dimensional imaging mode by using an ECAT HR+ tomograph (Siemens Molecular Imaging, Knoxville, Tenn). No-carrier-added (+)-11C DTBZ (9.25–37.0 TBq/mmol at the time of injection) was prepared as reported previously (36). Dynamic PET was performed for 60 minutes immediately after injection of a bolus of 55% of 555 MBq of (+)-11C DTBZ dose over the first 15–30 seconds of the study, whereas the remaining 45% of the dose was continuously infused over the next 60 minutes, resulting in stable arterial tracer levels and equilibrium with brain tracer levels after 30 minutes (37). All subjects underwent imaging while supine, with eyes and ears unoccluded, resting quietly in a dimly lit room.

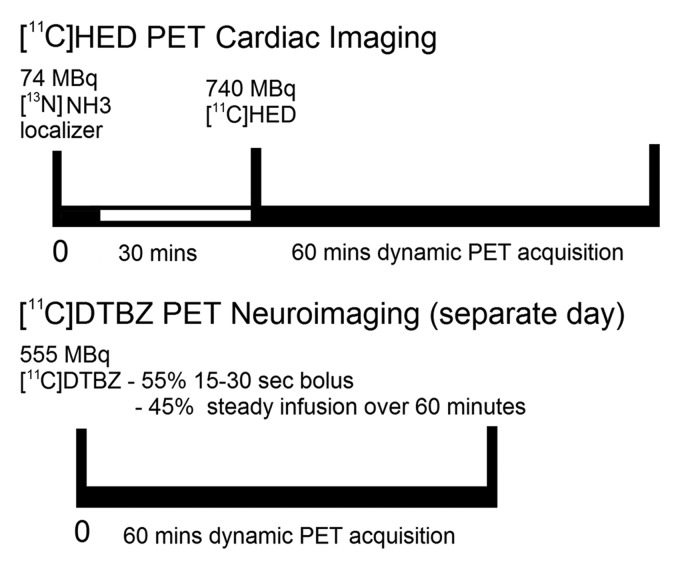

All dynamic PET imaging frames were spatially coregistered within subjects with a rigid body transformation to reduce the effects of subject motion during the imaging session. These motion-corrected PET frames were spatially coregistered to the MR images by using SPM8b software (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, England). Interactive Data Language image analysis software (Research Systems, Boulder, Colo) was used to manually trace volumes of interest on the MR image, including the striatum (caudate and putamen). Time-activity curves for each volume of interest were generated from the spatially aligned PET frames. DTBZ distribution volume ratio was then estimated by using the Logan plot graphical analysis method (38) with the time-activity curves as the input function and the neocortex as reference tissue for DTBZ, a reference region very low in VMAT2 binding sites, with the assumption that the nondisplaceable distribution is uniform across the brain at equilibrium (39). The imaging protocols are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Summary of functional sympathetic cardiac PET and nigrostriatal PET neuroimaging protocols.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with software (version 9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC; STATA, version 11.1, StataCorp, College Station, Tex). Group comparisons between two subgroups of IPD patients, those with normal findings or mild cardiac sympathetic denervation and those with severe cardiac sympathetic denervation, were performed by using the Student t test.

Results

Patient Characteristics

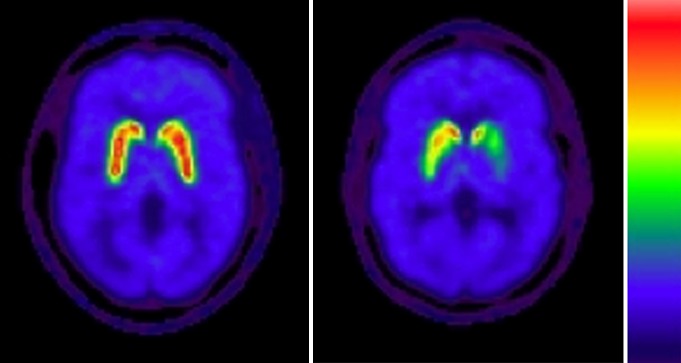

Disease severity in patients with IPD was classified as mild to moderate, with a mean disease duration of 5.4 years ± 3.4 (range, 1–14 years) and mean Hoehn and Yahr score of 2.2 ± 0.4 (range, 1–2.5). An IPD nigrostriatal denervation pattern typically consisted of asymmetric dopaminergic losses that were greater in the putamen than in the caudate nucleus. An example is shown in Figure 2. Patients had a mean Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale motor score of 28.6 ± 10.9 (range, 7–52).

Figure 2:

Transaxial parametric DTBZ PET VMAT2 binding images at level of striatum show normal intense uptake in control subject (left) and asymmetric predominant putaminal losses in patient with IPD (right).

Cardiac 11C HED Retention

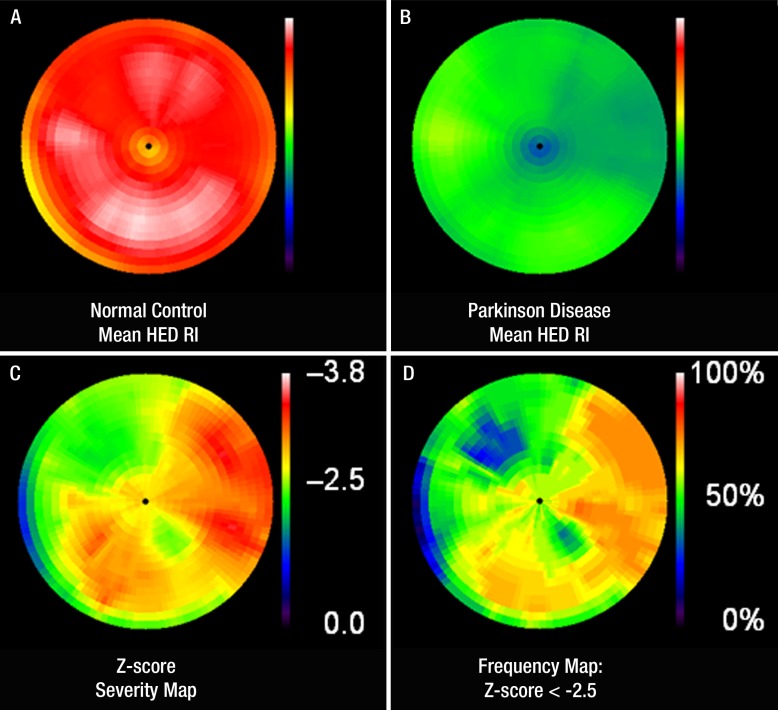

In the 33 control subjects, the mean 11C HED RI was 0.086 mL of blood per minute per milliliter of tissue ± 0.015. Table E1 (online) summarizes the demographic and clinical features and the global and regional 11C HED retention measurements in the 27 patients with IPD. The mean 11C HED RI in patients with IPD was 0.043 mL of blood per minute per milliliter of tissue ± 0.016 (P < .0001 vs control subjects). For the cohort of patients with IPD, the mean global denervation extent was 62% 6 38 (range, 0%–100%), the mean severity z score was -2.7 ± 1.2 (range, -3.6 to -2.63), and the mean SEP was -202 ± 131 (range, -358 to 0). As expected, profound cardiac denervation (global extent .50%) was seen in most patients (19 of 27 patients, 70%). Four patients had normal 11C HED studies (global extent = 0%) and four had partial, mild cardiac denervation (global extent ,25%). Figure 3 displays polar maps illustrating the mean 11C HED retention in the left ventricle of healthy control subjects and patients with IPD, the z score severity, and the frequency distributions of abnormal sympathetic innervation in these patients.

Figure 3:

A, B, Comparison polar maps of mean HED RI in, A, control subjects and, B, patients with IPD demonstrate severe global cardiac sympathetic denervation in patients with IPD. C, Segmental z score severity polar map generated by means of sector-to-sector comparison of HED RI in patients with IPD and control subjects shows the “characteristic” regional pattern of sympathetic denervation in IPD. Proximal lateral wall is most severely affected, with relative sparing of anterior and proximal septal walls. There is concordance in segmental distribution on both the z score severity polar map and, D, the frequency polar map representing the percentage of patients with IPD with an abnormal sector z score of 2.5 or less (ie, number of patients/27 3 100) displayed on a color scale of 0%–100%.

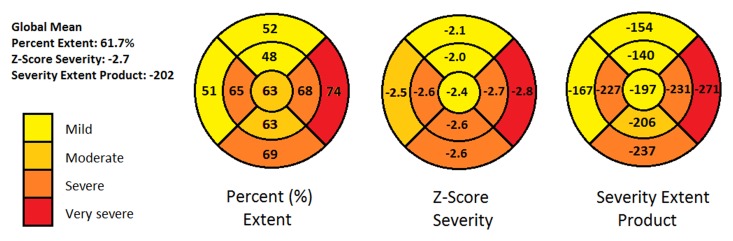

We performed a segmental analysis comparing mean global extent, severity, and SEP to the mean values in each of the nine segments. This analysis revealed relative sparing of proximal and distal anterior septal segments and proximal septal segments (mean extent, 48%–51%; severity z score, -2.47 to -2.0; SEP, -167 to -139). The proximal and distal lateral segments and proximal inferior segments were more severely affected (mean extent, 68%–73%; severity z score, -2.8 to -2.62; SEP, -271 to -230). Figure 4 presents a bull’s-eye representation of the segmental mean extent, severity, and SEP measurements.

Figure 4:

Bull’s-eye plots obtained with nine-segment model summarize segmental distribution of sympathetic denervation with respect to mean percentage extent, z score severity, and SEP in comparison to global mean measurements. Mean global denervation extent was 62% 6 38 (range, 0%–100%), mean severity z score was −2.7 ± 1.2 (range, −3.6 to −2.5), and mean SEP was −202 ± 131 (range, −358 to 0). Lateral wall displays greater extent and more severe reduction of 11C HED retention compared with anterior and proximal septal walls.

Figure E1 (online) shows the global and segmental distributions of SEP. The SEPs were used to divide patients into three categories: (a) those with normal findings (SEP = 0), (b) those with mild to moderate denervation (SEP ,0 to greater than −200), and (c) those with severe denervation (SEP less than or equal to −200). This distribution is summarized for the nine segments in Table E2 (online). Using these categories, we compared sympathetic denervation of the proximal lateral segment (normal findings = 6, severe denervation = 21) to that of the proximal anterior segment (normal findings = 9, mild to moderate denervation = 6, severe denervation = 12), finding that the proximal lateral segment is affected more severely and more frequently than other segments.

Relationship with Clinical and Nigrostriatal DTBZ PET Variables

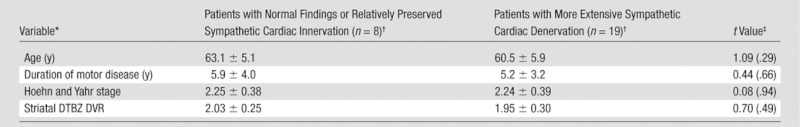

The Table shows the results of the group comparison of the clinical and DTBZ PET measures in the eight patients with either normal findings or partial mild cardiac denervation (global extent <25%) versus the 19 patients with more extensive cardiac denervation. There were no significant differences in age or duration of disease between the two groups. There were no significant differences in the extent of nigrostriatal denervation between the two groups.

Comparison of Clinical and DTBZ PET Variables in Patients with Normal Findings or Partial Mild Cardiac Denervation (Global Extent <25%) versus Patients with More Extensive Cardiac Denervation

DVR = distribution volume ratio.

Data are means ± standard deviations.

Data were determined with the Student t test. Numbers in parentheses are P values.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this investigation reports on the largest number of IPD patients studied with 11C HED PET imaging thus far. We have previously reported our initial experience in a mixed group of Parkinsonian subjects, including nine patients with IPD (27). Our current study confirms previous findings of extensive cardiac sympathetic denervation documented by using 123I MIBG imaging, supporting the notion that cardiac sympathetic imaging might be used as a relatively sensitive diagnostic test for IPD. Many authors have endorsed the potential of cardiac sympathetic imaging to differentiate IPD from other Parkinsonian disorders (3,12,15,18,20,26,40). Nevertheless, we and others have reported that cardiac sympathetic neuronal loss also occurs in multiple system atrophy (4,13,25,27).

We did not find significant differences in the degree of nigrostriatal denervation between the patients with normal findings or relatively preserved cardiac sympathetic innervation and those with more severe cardiac sympathetic denervation. Furthermore, we did not find differences in mean age or duration of motor disease between those groups. Reductions in 123I MIBG uptake in IPD have been previously reported to correlate with Hoehn and Yahr severity scores (7,15,17,40), the presence of visual hallucinations (10), midline symptoms of speech, posture, and gait dysfunction (8), and deficits in olfactory testing (8,11). There is currently no consensus regarding a relationship between MIBG uptake and patient outcome measurements in IPD, and no studies comparing 11C HED PET and 123I MIBG imaging have been reported to date.

Histopathologic studies of degeneration of cardiac sympathetic nerves in IPD, using paravertebral sympathetic ganglia tissue and cardiac tissue derived from anterior left ventricular walls, stained with tyrosine hydroxylase and neurofilament antibodies to confirm sympathetic nervous tissue, demonstrated α-synuclein aggregates in the neuronal somata with absent tyrosine hydroxylase and neurofilament immunoreactivity in the distal sympathetic axons (13,23,25). Fluorine 18 (18F) fluorodopamine PET studies in patients with IPD have shown relatively lower sympathetic innervation in the lateral wall, with sparing of the septum, which was attributed to loss of functional cardiac sympathetic nerve terminals (41,42). Furthermore, in patients who underwent serial 18F fluorodopamine PET imaging with a mean interval of 2 years from the first scan, radioactivity on the second study was decreased by 31% in the left ventricle free wall compared with only 16% in the septum (42). Therefore, the segmental patterns of left ventricular sympathetic denervation in IPD appear comparable between 11C HED PET and previous 18F fluorodopamine PET imaging studies.

Cardiac sympathetic neurons within the right coronary, left coronary, and left lateral cardiac nerves travel with the coronary arteries in the subepicardial layer before penetrating the myocardium. The segmental pattern we observed is not explained by either greater susceptibility to injury of the neurons supplying the lateral left ventricular wall or regional differences in neuronal density. First, the 11C HED distribution in the hearts of healthy subjects has been described as homogeneous (28,30). Second, z score analysis would correct for any regional differences in 11C HED distribution.

Autonomous cardiac sympathetic innervation in humans is complex, with efferent cardiopulmonary and more distal cardiac nerves demonstrating overlapping segmental territories in the left ventricle. A plausible explanation for the observed pattern, based on human anatomy and experiments in nonhuman species, is that the lateral wall and, to a lesser extent, posterior (inferior) wall supplied by the left lateral cardiac nerve has the least amount of overlapping innervation (43). Conversely, the anterior and septal walls are innervated by the left coronary cardiac nerve, which derives branches from right and left dorsal mediastinal (medial and lateral) cardiopulmonary nerves that contain axonal projections from the right and left stellate and middle cervical ganglia, respectively (43). In a canine model, sectioning of the left lateral cardiac nerve led to decreased inotropic responses in the lateral and posterior walls following left middle cervical ganglion stimulation (44). However, sectioning of individual major sympathetic cardiopulmonary nerves failed to abolish left ventricular inotropic responses after ipsilateral middle cervical ganglion stimulation, suggesting possible redundant innervation from contralateral cervical ganglia (44).

A limitation of this study was that concurrent myocardial perfusion imaging was not performed in our patient cohort, unlike for studies investigating 11C HED PET in patients with congestive cardiac failure, diabetic autonomic neuropathy, or myocardial infarction. Despite this, we do not believe that undiagnosed coronary artery disease could have contributed to our observed findings. None of the patients with IPD had angina-like symptoms, a history of cardiac disease, or abnormal electrocardiographs. In addition, none of the patients was taking antianginal medications. Furthermore, the pattern of more severe proximal lateral left ventricle involvement is not typical for coronary artery disease. Early 11C HED PET images at 5 minutes after injection during the “perfusion” phase were inspected for the four patients with IPD and mild denervation and did not reveal any defects. Another limitation of our study was that we were unable to perform any comparison between 11C HED PET and 123I MIBG. To more fully understand the process of cardiac denervation in IPD, it may be necessary to evaluate patients at even earlier stages of disease with short-interval serial studies and to perform comparative studies between 11C HED PET and 123I MIBG imaging to determine which radiotracer more closely correlates with clinical parameters.

In conclusion, cardiac sympathetic denervation is extensive in IPD and affects most patients at an early stage in the disease course. The segmental pattern of cardiac sympathetic denervation involves the proximal lateral left ventricular wall most severely, with relative sparing of the anterior and proximal septal walls. This suggests a characteristic pattern of neuronal sympathetic degeneration in IPD.

Advances in Knowledge.

• Most patients with Parkinson disease have severe cardiac sympathetic denervation.

• With three-dimensional tomographic analysis of carbon 11 (11C) hydroxyephedrine (HED) retention in the left ventricle, it was demonstrated that the cardiac sympathetic denervation in Parkinson disease follows a distinct regional pattern.

• The lateral wall of the left ventricle is affected most severely and frequently, whereas the anterior and septal walls are relatively spared in comparison.

• Knowledge of the regional pattern of cardiac sympathetic denervation contributes to our understanding of Parkinson disease as a degenerative disease of autonomic neurons.

Implication for Patient Care.

• 11C HED PET provides three-dimensional tomographic data demonstrating severe cardiac sympathetic denervation in most patients with Parkinson disease and may have a role as a diagnostic test.

Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: K.K.W. No potential conflicts of interest to disclose. D.M.R. No potential conflicts of interest to disclose. R.A.K. Financial activities related to the present article: none to disclose. Financial activities not related to the present article: is a paid consultant for Johnson & Johnson, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. Other relationships: none to disclose. K.A.F. Financial activities related to the present article: none to disclose. Financial activities not related to the present article: is a paid consultant for MIMvista, GE Healthcare, Bayer-Schering Pharma, and Avid Radiopharmaceuticals; institution has a grant or grant pending from GE Healthcare, Siemens, and Avid Radiopharmaceuticals; owns stock or stock options in GE Healthcare, Novo-Nordisc, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Medtronic. Other relationships: none to disclose. N.I.B. No potential conflicts of interest to disclose. S.G. Financial activities related to the present article: none to disclose. Financial activities not related to the present article: has a grant or grant pending from GE Healthcare. Other relationships: none to disclose.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Arijit Bhaumik, BA, Kris Wernette, RN, and Christine Minderovic, BA, for assistance with the study.

Received December 21, 2011; revision requested January 31, 2012; revision received March 23; accepted April 2; final version accepted April 13.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants P01 NS015655 and R01-HL079540).

Abbreviations:

- DTBZ

- dihydrotetrabenazine

- HED

- hydroxyephedrine

- IPD

- idiopathic Parkinson disease

- MIBG

- metaiodobenzylguanidine

- RI

- retention index

- SEP

- severity-extent product

- VMAT2

- vesicular monoamine transporter type 2

References

- 1.Goldstein DS. Imaging of the autonomic nervous system: focus on cardiac sympathetic innervation. Semin Neurol 2003;23(4):423–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akincioglu C, Unlu M, Tunc T. Cardiac innervation and clinical correlates in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Nucl Med Commun 2003;24(3):267–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braune S, Reinhardt M, Schnitzer R, Riedel A, Lücking CH. Cardiac uptake of [123I]MIBG separates Parkinson’s disease from multiple system atrophy. Neurology 1999;53(5):1020–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Druschky A, Hilz MJ, Platsch G, et al. Differentiation of Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy in early disease stages by means of I-123-MIBG-SPECT. J Neurol Sci 2000;175(1):3–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein DS, Holmes C, Cannon RO, III, Eisenhofer G, Kopin IJ. Sympathetic cardioneuropathy in dysautonomias. N Engl J Med 1997;336(10):696–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldstein DS, Holmes CS, Dendi R, Bruce SR, Li ST. Orthostatic hypotension from sympathetic denervation in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 2002;58(8):1247–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamada K, Hirayama M, Watanabe H, et al. Onset age and severity of motor impairment are associated with reduction of myocardial 123I-MIBG uptake in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74(4):423–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JS, Lee KS, Song IU, et al. Cardiac sympathetic denervation is correlated with Parkinsonian midline motor symptoms. J Neurol Sci 2008;270(1-2):122–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JS, Lee PH, Lee KS, et al. Cardiac [123I]metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy for vascular Parkinsonism. Mov Disord 2006;21(11):1990–1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitayama M, Wada-Isoe K, Irizawa Y, Nakashima K. Association of visual hallucinations with reduction of MIBG cardiac uptake in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci 2008;264(1-2):22–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee PH, Yeo SH, Kim HJ, Youm HY. Correlation between cardiac 123I-MIBG and odor identification in patients with Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy. Mov Disord 2006;21(11):1975–1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsui H, Udaka F, Oda M, Kubori T, Nishinaka K, Kameyama M. Metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy at various parts of the body in Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy. Auton Neurosci 2005;119(1):56–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orimo S, Amino T, Itoh Y, et al. Cardiac sympathetic denervation precedes neuronal loss in the sympathetic ganglia in Lewy body disease. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2005;109(6):583–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orimo S, Oka T, Miura H, et al. Sympathetic cardiac denervation in Parkinson’s disease and pure autonomic failure but not in multiple system atrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;73(6):776–777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saiki S, Hirose G, Sakai K, et al. Cardiac 123I-MIBG scintigraphy can assess the disease severity and phenotype of PD. J Neurol Sci 2004;220(1-2):105–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Satoh A, Serita T, Seto M, et al. Loss of 123I-MIBG uptake by the heart in Parkinson’s disease: assessment of cardiac sympathetic denervation and diagnostic value. J Nucl Med 1999;40(3):371–375 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spiegel J, Hellwig D, Farmakis G, et al. Myocardial sympathetic degeneration correlates with clinical phenotype of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2007;22(7):1004–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takatsu H, Nagashima K, Murase M, et al. Differentiating Parkinson disease from multiple-system atrophy by measuring cardiac iodine-123 metaiodobenzylguanidine accumulation. JAMA 2000;284(1):44–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takatsu H, Nishida H, Matsuo H, et al. Cardiac sympathetic denervation from the early stage of Parkinson’s disease: clinical and experimental studies with radiolabeled MIBG. J Nucl Med 2000;41(1):71–77 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taki J, Nakajima K, Hwang EH, et al. Peripheral sympathetic dysfunction in patients with Parkinson’s disease without autonomic failure is heart selective and disease specific. Eur J Nucl Med 2000;27(5):566–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshita M, Hayashi M, Hirai S. Iodine 123–labeled meta-iodobenzylguanidine myocardial scintigraphy in the cases of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, multiple system atrophy, and progressive supranuclear palsy [in Japanese]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 1997;37(6):476–482 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshita M, Taki J, Yokoyama K, et al. Value of 123I-MIBG radioactivity in the differential diagnosis of DLB from AD. Neurology 2006;66(12):1850–1854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amino T, Orimo S, Itoh Y, Takahashi A, Uchihara T, Mizusawa H. Profound cardiac sympathetic denervation occurs in Parkinson disease. Brain Pathol 2005;15(1):29–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orimo S, Kanazawa T, Nakamura A, et al. Degeneration of cardiac sympathetic nerve can occur in multiple system atrophy. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2007;113(1):81–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orimo S, Uchihara T, Nakamura A, et al. Axonal α-synuclein aggregates herald centripetal degeneration of cardiac sympathetic nerve in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2008;131(Pt 3):642–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berding G, Schrader CH, Peschel T, et al. [N-methyl 11C]meta-hydroxyephedrine positron emission tomography in Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2003;30(1):127–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raffel DM, Koeppe RA, Little R, et al. PET measurement of cardiac and nigrostriatal denervation in Parkinsonian syndromes. J Nucl Med 2006;47(11):1769–1777 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bengel FM, Schwaiger M. Assessment of cardiac sympathetic neuronal function using PET imaging. J Nucl Cardiol 2004;11(5):603–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Münch G, Ziegler S, Nguyen N, Hartmann F, Watzlowik P, Schwaiger M. Scintigraphic evaluation of cardiac autonomic innervation. J Nucl Cardiol 1996;3(3):265–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwaiger M, Kalff V, Rosenspire K, et al. Noninvasive evaluation of sympathetic nervous system in human heart by positron emission tomography. Circulation 1990;82(2):457–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gelb DJ, Oliver E, Gilman S. Diagnostic criteria for Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol 1999;56(1):33–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bohnen NI, Albin RL, Koeppe RA, et al. Positron emission tomography of monoaminergic vesicular binding in aging and Parkinson disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2006;26(9):1198–1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pop-Busui R. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy in diabetes: a clinical perspective. Diabetes Care 2010;33(2):434–441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenspire KC, Haka MS, Van Dort ME, et al. Synthesis and preliminary evaluation of carbon-11-meta-hydroxyephedrine: a false transmitter agent for heart neuronal imaging. J Nucl Med 1990;31(8):1328–1334 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raffel DM, Corbett JR, del Rosario RB, et al. Clinical evaluation of carbon-11-phenylephrine: MAO-sensitive marker of cardiac sympathetic neurons. J Nucl Med 1996;37(12):1923–1931 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jewett DM, Kilbourn MR, Lee LC. A simple synthesis of [11C]dihydrotetrabenazine (DTBZ). Nucl Med Biol 1997;24(2):197–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koeppe RA, Frey KA, Kume A, Albin R, Kilbourn MR, Kuhl DE. Equilibrium versus compartmental analysis for assessment of the vesicular monoamine transporter using (+)-α-[11C]dihydrotetrabenazine (DTBZ) and positron emission tomography. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1997;17(9):919–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Ding YS, Alexoff DL. Distribution volume ratios without blood sampling from graphical analysis of PET data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1996;16(5):834–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koeppe RA, Frey KA, Kuhl DE, Kilbourn MR. Assessment of extrastriatal vesicular monoamine transporter binding site density using stereoisomers of [11C]dihydrotetrabenazine. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1999;19(12):1376–1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kashihara K, Ohno M, Kawada S, Okumura Y. Reduced cardiac uptake and enhanced washout of 123I-MIBG in pure autonomic failure occurs conjointly with Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. J Nucl Med 2006;47(7):1099–1101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldstein DS, Holmes C, Li ST, Bruce S, Metman LV, Cannon RO., III Cardiac sympathetic denervation in Parkinson disease. Ann Intern Med 2000;133(5):338–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li ST, Dendi R, Holmes C, Goldstein DS. Progressive loss of cardiac sympathetic innervation in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 2002;52(2):220–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Janes RD, Brandys JC, Hopkins DA, Johnstone DE, Murphy DA, Armour JA. Anatomy of human extrinsic cardiac nerves and ganglia. Am J Cardiol 1986;57(4):299–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Janes RD, Johnstone DE, Brandys JC, Armour JA. Functional and anatomical variability of canine cardiac sympathetic efferent pathways: implications for regional denervation of the left ventricle. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 1986;64(7):958–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.