Abstract

The tautomerism and corresponding transition states of four authentic HIV-1 integrase (IN) inhibitor prototype structures, α,γ-diketo acid, α,γ-diketotriazole, dihydroxypyrimidine carboxamide, and 4-quinolone-3-carboxylic acid were investigated at the B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level in vacuum and in aqueous solvent model. To study the possible chelating modes of these tautomers with two magnesium ions, a process important for inhibition, we modeled an assembly of three formic acids, four water molecules, and two Mg2+ as a template mimicking the binding site of IN. The DFT calculation results show that deprotonated enolized or phenolic hydroxyl groups of specific tautomers in water lead to the most stable complexes, with the two magnesium ions separated by a distance of approximately 3.70 to 3.74 Å, and with each magnesium ion at the center of an octahedron. The drug candidate GS-9137 (Gilead), based on the 4-quinolone-3-carboxylic acid scaffold, and its analogues form similar but different chelating modes. When one water molecule in the complex is replaced by a methanol molecule, which mimics the terminal 3'-OH of viral DNA, a good chelating complex is retained. This supports the hypothesis that in the binding site of IN after 3'-processing, the terminal 3'-OH of viral DNA interacts with one Mg2+ by chelation.

Keywords: chelates, density functional calculations, HIV-1 integrase, inhibitors, tautomerism

Introduction

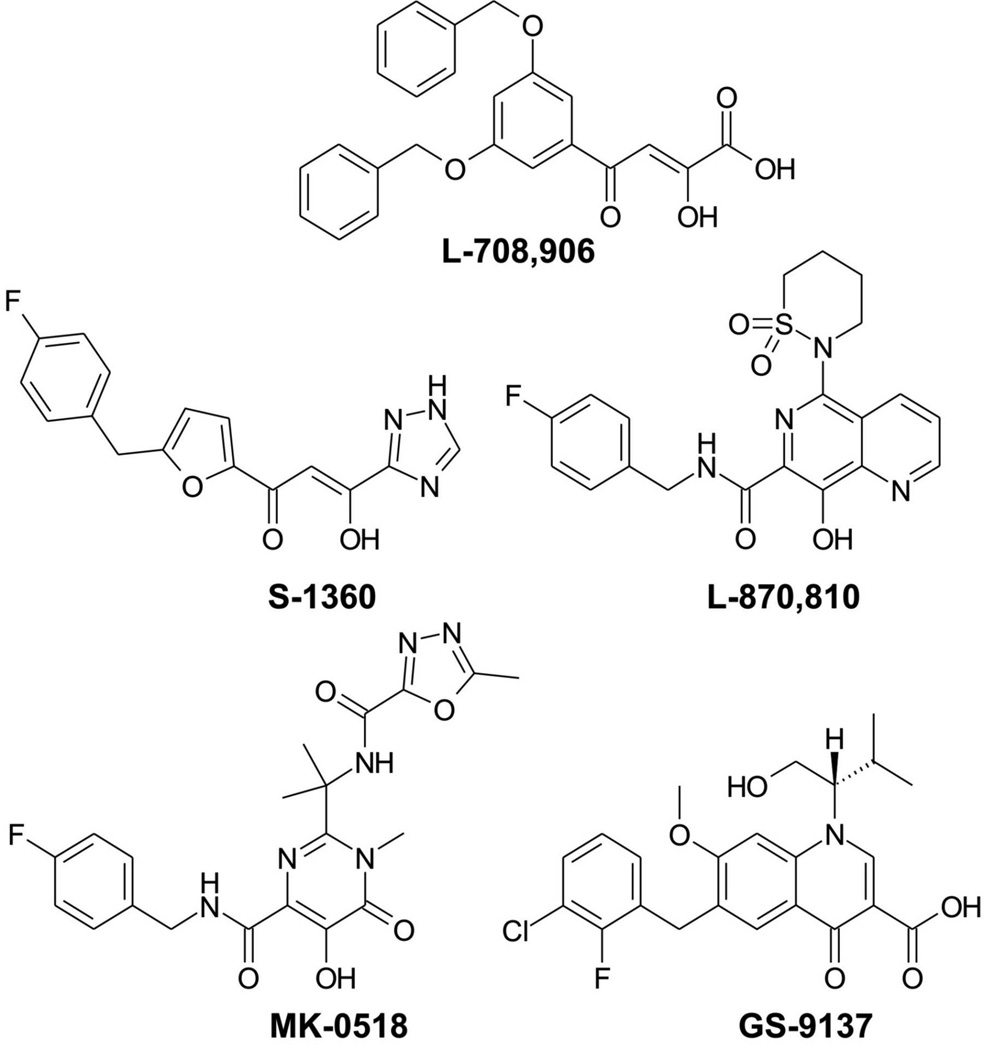

It took almost twenty years of development of HIV-1 IN inhibitors to proceed through the identification of the first “authentic” class of IN inhibitors, the diketo acids,[1] to the approval in 2007 of the first IN-inhibition based anti-HIV agent, compound MK-0518 by Merck (raltegravir, marketed as ISENTRESS®), a bioisostere of diketo acid.[2–4] In this sense, we call “authentic” those HIV-1 IN inhibitors that revealed good anti-viral activity. Figure 1 shows the structures of MK-0518 and four other typical authentic HIV-1 IN inhibitors. (For various identifiers for these compounds, including InChIKey, FICuS,[5] and SMILES, see Table S1 in Supporting Information.) Among those, L-708,906 (Merck) was one of the first compounds discovered that potently inhibited IN strand transfer; S-1360 (Shionogi) and L-870,810 (Merck) went as far as phase II in clinical trials but further development was halted; GS-9137 (elvitegravir, Gilead) is in phase III evaluation at the time of writing.

Figure 1.

Typical authentic HIV-1 IN inhibitors.

All these authentic HIV-1 IN inhibitors share the property that they selectively inhibit the strand transfer (ST) reaction more potently than the 3'-end processing (3'-P) reaction. ST and 3'-P are two distinct reactions involving phosphate ester modifications catalyzed by IN:[6] HIV-1 IN first assembles on the newly synthesized transcript and removes two bases from both 3'-ends of the double-stranded viral DNA (the 3'-P reaction); subsequently, after transport of the pre-integration complex into the nucleus, IN catalyzes the joining of these 3'-ends to opposite strands of the host DNA, offset by five base pairs (the ST reaction). It has been observed that for the two catalytic functions of the enzyme, there is the prerequisite for divalent metal to be present such as Mn2+ or Mg2+, the latter being assumed to be the physiologically relevant species.[7]

Regarding chemical structure characteristics of the authentic IN inhibitors, all these compounds possess at least two distinct regions: an aromatic hydrophobic region, and a chelating region. Except for GS-9137, the chelating region of all these compounds is represented by a diketo acid motif or a bioisostere of diketo acid. In structural terms, this means they have three functional groups in a coplanar conformation, which are assumed to chelate two magnesium ions in the so-called two-metal-ion mechanism.[8]

Although the coming on the market of raltegravir testifies to the advances the development of HIV-1 IN inhibitors as anti-AIDS agents has made, we still do not know exactly how the inhibitors bind to either the enzyme or its substrate, the viral DNA. The reason for this is the lack of experimental structures of the full-length protein complexed with the viral DNA. The verdict is still out on how useful very recently published crystal structures of full-length IN of the prototype foamy virus (PFV) complexed with its cognate DNA plus authentic HIV-1 IN inhibitors truly will be for anti-HIV-1 drug development given the low sequence similarity of PVF IN compared with HIV-1 IN and the marginal crystallographic resolution (around 3Å) of these structures.[9] In previous work, we have tried to develop IN-DNA models to probe the enzyme-DNA binding in a general manner,[10] and subsequently used these models for drug discovery.[11] In this study, we attempt to drill down to the binding of inhibitors in great detail.

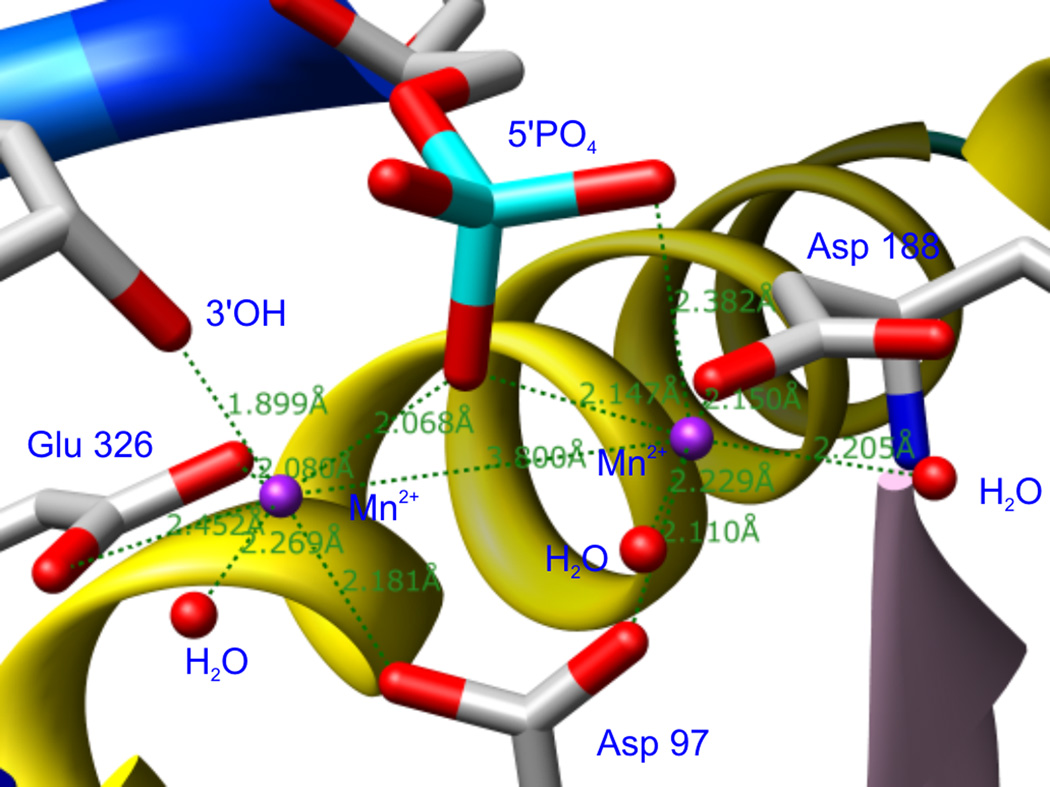

The Tn5 transposase (Tnp), like IN a member of the family of polynucleotidyl transferases, can be considered an excellent surrogate model for IN,[12] not only because some compounds can inhibit both Tn5 Tnp and HIV-1 IN in vitro,[13] but because there are many similarities between the catalytic mechanism and the active site architecture of these two enzymes. Both of them, in particular, share a high degree of structural similarity of the catalytic triad of acidic residues, which chelate divalent metal ions required for catalysis. An X-ray cocrystal structure of Tn5 Tnp-DNA-metal ternary complex has been solved.[14] Two Mn2+ ions are present in the active site at a mutual distance of 3.80 Å. One Mn2+ is coordinated by the two oxygen atoms of Glu 326, one oxygen atom of Asp 97, the terminal deoxyribose 3’-OH of the transferred strand and a water molecule. The other one is coordinated by one oxygen atom of Asp 97, one oxygen atom of Asp 188, two oxygen atoms of the non-transferred strand 5’-phosphate and two water molecules (Figure 2). The catalytic triad residues, i.e., Asp 97, Asp 188 and Glu 326, are referred to as the DDE motif and are conserved among Tnps and retroviral INs. For HIV-1 IN, the DDE motif is comprised of Asp 64, Asp 116 and Glu 152. It is believed that these three residues would assume a similar spatial arrangement as the corresponding ones in Tn5 Tnp. As revealed from available X-ray structures of the HIV-1 IN core domain, Asp 64 and Asp 116 form a coordination complex with one Mg2+.[15] It has been proposed that a second Mg2+ can be most likely chelated by Glu 152 and Asp 64 once HIV-1 IN binds its DNA substrate.[7] As to the metal ions, it is commonly accepted that Mg2+ is a more reasonable cofactor for integration in cells.[8, 16]

Figure 2.

The DDE motif in the Tn5 Tnp active site.

Based on these facts, we decided to use the DDE motif of Tn5 Tnp as the template to partly mimic the binding site of IN and then explore how the IN inhibitors chelate the Mg2+ through use of B3LYP density functional theory (DFT) calculations both in vacuum and in aqueous solution. The purpose of this effort is to offer theoretical results to help design moieties capable of chelating two Mg2+ and aid in the future development of inhibitors with novel scaffolds.

A serious complication for predicting molecular recognition and therefore drug discovery arises, however, from the fact that some of the authentic IN inhibitors have multiple tautomers.[17] Questions in this context are: Which tautomer(s) of a specific inhibitor exist in vacuum vs. aqueous solution? How do they convert into each other? Does a molecule bind preferably in one distinct tautomer or is tautomeric heterogeneity of binding possible? Is the most stable tautomeric form in aqueous solution also the most stable form in the active site of a protein? Would the binding environment affect the existing states of various tautomers? Before investigating the chelating modes of the IN inhibitors, it therefore seemed appropriate to us to attempt to provide answers to these questions.

The common view is that the binding environment within a protein is a very specific one: Apolar, polar, acidic or basic side chains create local pHs, alter side chain pKa values and consequently influence the functional groups of the ligand. In addition to these factors, the presence of metal ions and water can influence the tautomeric states of a ligand, and in such a context, ligands may be ionized or assume an excited tautomeric state.[18]

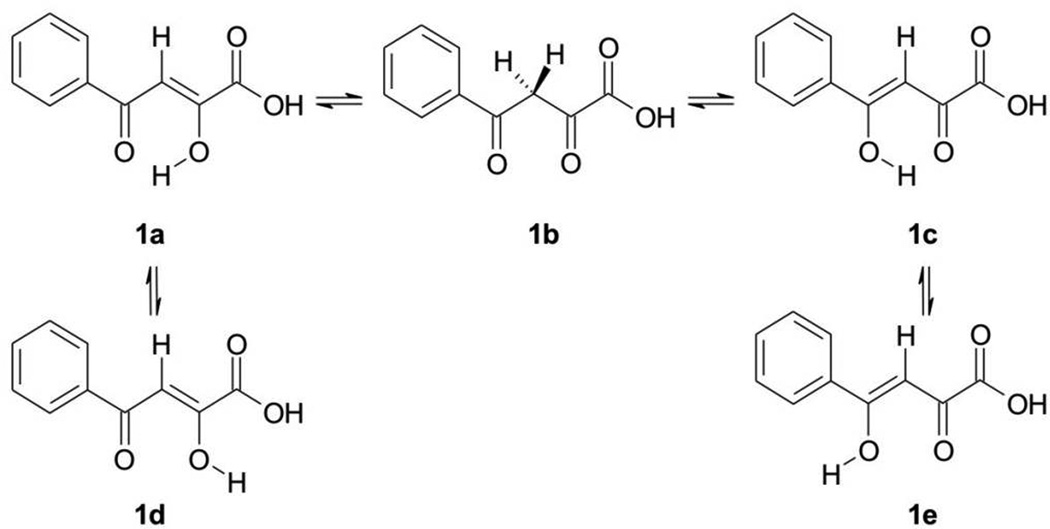

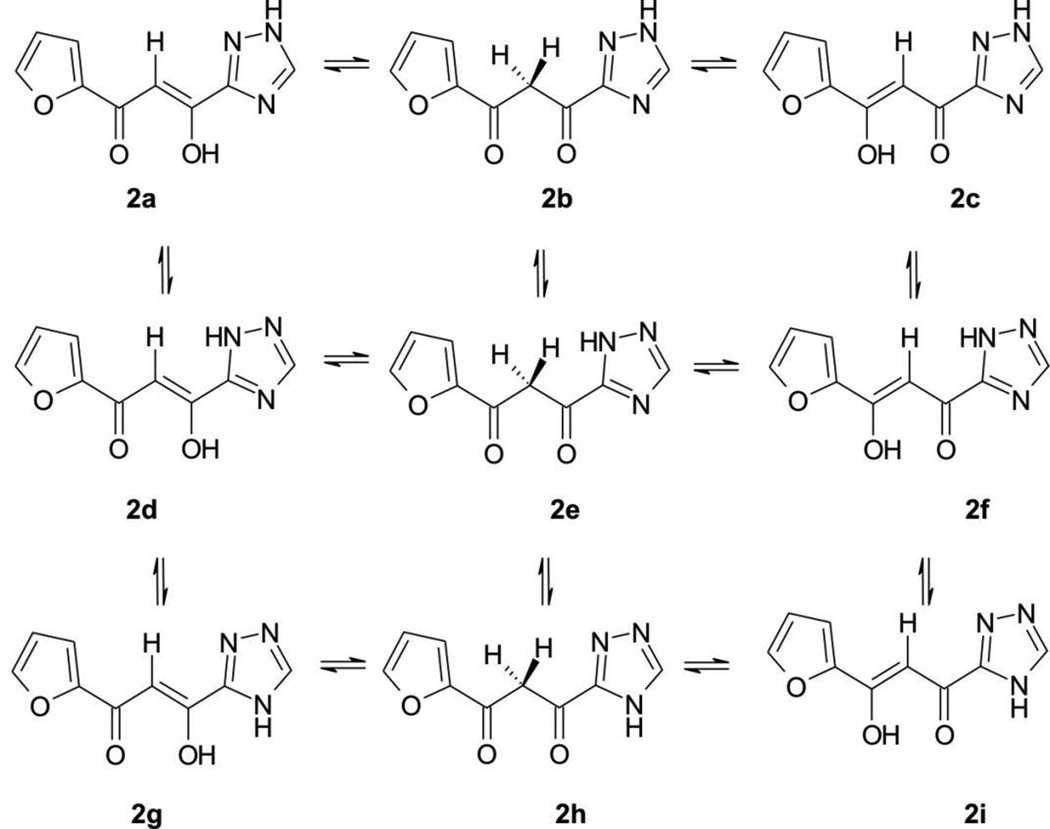

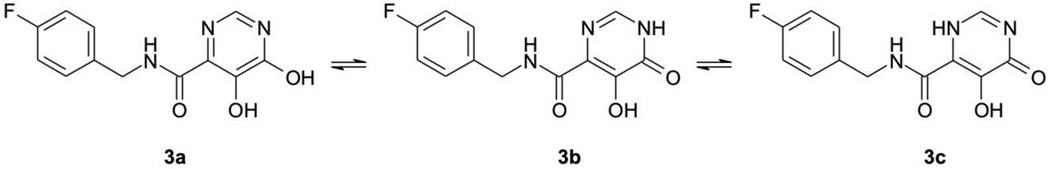

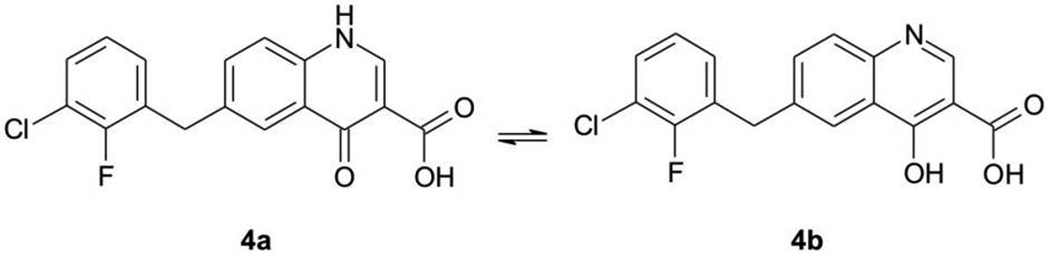

For example, the chelating moiety of L-708,906 has at least three tautomers (Figure 3); the chelating moiety of S-1360 has at least nine tautomers (Figure 4). The chelating moieties of L-870,810, MK-0518 and GS-9137 do not have tautomers. However, some analogues of MK-0518 do (e.g., 3a,[19] with three possible tautomers, Figure 5), as do some analogues of GS-9137 (e.g., 4a,[20] with two possible tautomers, Figure 6).

Figure 3.

Possible tautomers (1a – 1c) and rotamers (1d – 1e) of α,γ-diketo acid.

Figure 4.

Possible tautomers (2a – 2i) of α,γ-diketotriazole.

Figure 5.

Possible tautomers (3a – 3c) of dihydroxypyrimidine carboxamide. The compound with an IC50 = 0.06 µM for ST inhibition is shown as an example.

Figure 6.

Possible tautomers (4a – 4b) of 4-quinolone-3-carboxylic acid. The compound with an IC50 = 0.0435 µM for ST inhibition is shown as an example.

Very few theoretical studies have been reported, to our knowledge, on such tautomers.[21,22] Even less appears to be known about tautomerism of ligands in the binding site of proteins. We therefore felt that it would be useful and appropriate to perform B3LYP DFT calculations on the tautomers mentioned above and their chelating modes with two Mg2+, the DDE motif, and several water molecules.

Computational Methods

Conformational Search

To obtain global energy minima, all structures (1a – 1e, 2a – 2i, 3a – 3c, 4a – 4b) were subject to conformational search using MOE (version 2007.09)[23] or MarcoModel 9.6[24] depending on whether the structures were intended for DFT calculation in vacuum or in aqueous solution. The search methods employed in MOE and MacroModel were systematic search and torsional sampling, respectively. Both employed MMFF94s as the force field. For the searches in MacroModel, water was chosen as solvent. The three lowest energy conformations of each tautomer or rotamer were optimized by DFT calculations performed as follows. The calculated lowest energy conformations were taken as the global minima and then used in the further DFT calculations.

Quantum Chemical Calculations

The quantum chemical calculations were performed utilizing DFT with the Gaussian 03[25] suite of programs. For the tautomers and complexes, DFT was employed using the B3LYP functional and the 6-311++G(d,p) basis set for geometric optimizations without any geometrical restrictions. Harmonic vibrational frequencies were computed at the same level of theory to verify the nature of minima.

To estimate the effect of the solvent, here water, on the geometries and relative stabilities of all tautomers, rotamers, transition states and complexes, we employed the self-consistent reaction field theory (SCRF) polarizable continuum model (PCM) with a dielectric constant ε= 78.39 as implemented in Gaussian, again at the B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level of theory.

To study the modes in which the tautomers chelate two magnesium ions, we modeled an assembly of three formic acids, which take the places of the residues Asp 64, Asp 116 and Glu 152, four water molecules, and two magnesium ions. These components of the chelation complexes were arranged according to the DDE coordinates of Tn5 Tnp (PDB ID 1MUS)[14] to partly mimic the binding site of IN. These calculations also employed B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) both in vacuum and in aqueous solvent model.

Results and Discussion

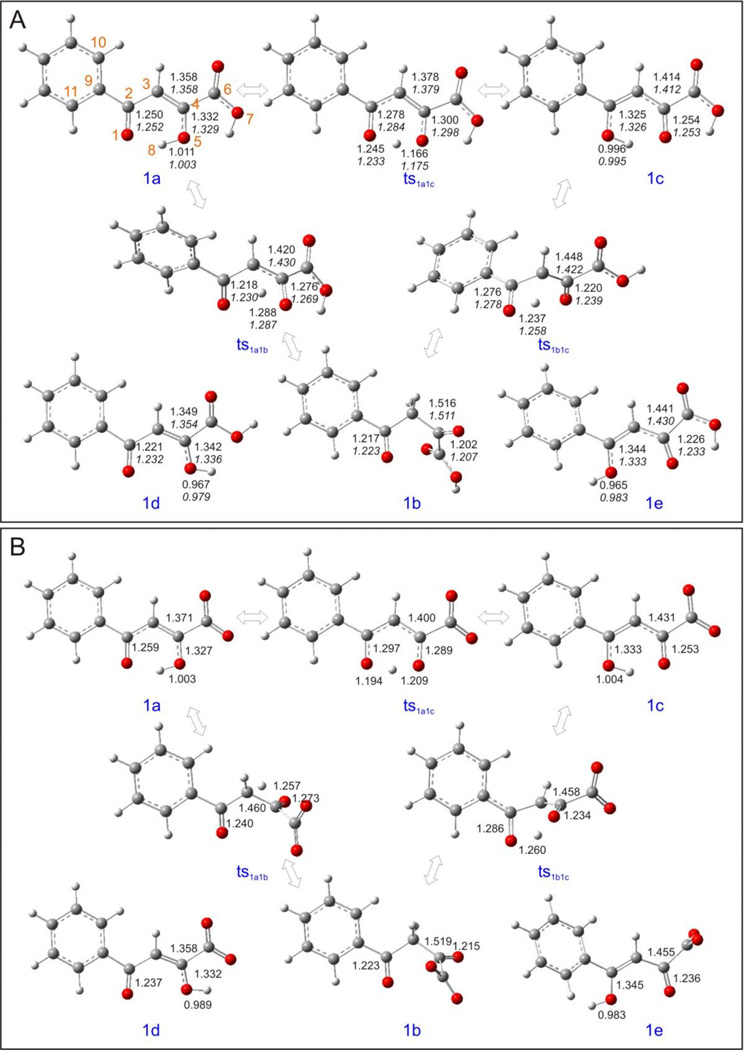

DFT calculations for tautomers and rotamers of α,γ-diketo acid

The results of the vacuum calculation of the relative stability of the structures 1a – 1e are shown in Table S2 and Figure 7. The most stable tautomer is 1c, an enol tautomer; the second most stable tautomer is 1a, another enol tautomer, with a slightly higher energy than 1c by 2.476 kcal/mol. As shown in Figure 8, the two optimized structures of 1a and 1c are planar, indicating there is no conflict between the two hydrogen atoms connected to carbon atoms 3 and 10, respectively. In contrast, 1d and 1e have very high energies relative to the lowest tautomer, 1c, and minimized structures of both are not planar. In general, the chelating moieties are still in plane, but they are twisted away from the benzene rings because of the repulsion between the two hydrogen atoms mentioned above. Tautomer 1b, the real diketo form, is 10.241 kcal/mol less stable than 1c. Neither the chelating moiety nor the whole structure of 1b is planar. All these effects are brought about by the intramolecular hydrogen bonds that only exist in 1a and 1c.

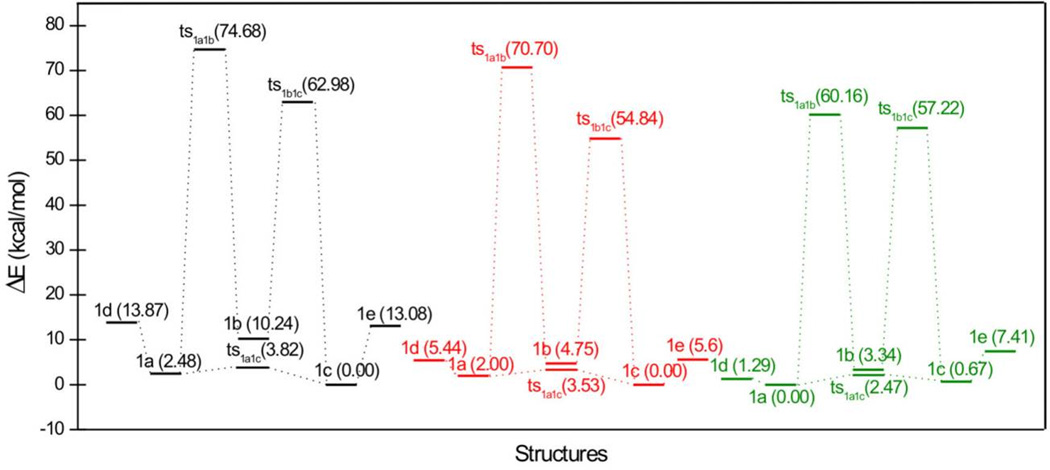

Figure 7.

Relative energies (in kcal/mol) of tautomers (1a – 1c), rotamers (1d – 1e) and their associated transition states. Black: vacuum; red: aqueous solvent without deprotonation; green: aqueous solvent with deprotonation.

Figure 8.

Optimized geometries of 1a – 1e and their associated transition states calculated at the B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level. (A) Upper values are the parameters in vacuum, lower values in italic are the parameters in aqueous solution; (B) parameters in aqueous solution with deprotonated acid groups.

In vacuum, three transition states of 1a – 1c were found (Figure 7). The interconversion barriers between 1a and 1b, and between 1b and 1c are almost insurmountable. In contrast, the one between 1a and 1c is totally achievable since the energy barrier is only 3.816 kcal/mol. It is believed that in “real”, i.e. non-vacuum, environments, a tautomer can be converted into another one directly or indirectly in various ways, but in vacuum, tautomers can be converted only by proton transfer. Thus with no other medium present, our results indicate that in vacuum, benzoylpyruvic acid exists predominantly in the two forms 1a and 1c.

In aqueous solution, four of these tautomers and rotamers (1b being the exception) have two ionizable groups, therefore these species can assume several different forms depending on whether the ionizable groups are deprotonated or not. Williams et al. measured the two ionizable groups’ pKa values, and found them to be 3 – 4 for the carboxylic acid group and 8 – 10 for the enolized hydroxyl group.[26] The ionization of the enolized hydroxyl group is not facile, not only because of its weak acidity, but also because of another stronger acid group being present in the same molecule, so the two predominant species in aqueous solution are the one without deprotonation and one with the deprotonated acid group, although some measurable quantities of the dianionic species derived from the keto-enol form have been reported to exist in equilibrium at physiological conditions (pH = 7.4).[27–29]

For the protonated species, the tautomeric preference is the same as in vacuum: the order of stability is still 1c > 1a > 1b > 1d > 1e. However, aqueous solvent increases the stability of all tautomers and rotamers by about 13 ~ 21 kcal/mol. The calculated interconversion barriers between 1a and 1b and between 1b and 1c are still effectively insurmountable, although the values have decreased. The relative energy of transition state ts1a1c also decreases, making it much easier for 1a and 1c to convert into each other in aqueous solution than in vacuum. For the species with deprotonated acid groups, the situation changes somewhat. The order of stability is now 1a > 1c > 1d > 1b > 1e. The energy differences are considerably reduced except for tautomer 1e.

We need to stress, however, that the PCM method we employed here does not consider the presence of explicit solvent molecules, consequently specific solute-solvent interactions are not described and the calculated solvation effects arise only from reciprocal solute-solvent electrostatic polarization. Additionally, the tautomeric equilibria are heavily affected by the existence of acid or base. We therefore assume that in real aqueous solution, tautomeric conversion would be considerably more facile than calculated, whether the carboxylic acid groups lose their proton or not. From this would follow that several kinds of species exist in aqueous solution.

Aliev et al. performed X-ray diffraction analysis on benzoylpyruvic acid,[30] which in the solid state exists in the 1a form with the carboxylic acid group adopting a different orientation from the one having been calculated here, caused by the formation of hydrogen-bonded dimeric associates. The main points here that are consistent with our calculation results are: (1) the molecule is planar; (2) some structural parameters are close to those we calculated (Figure S1).

DFT calculations for tautomers of α,γ-diketotriazole

The gas-phase calculated order of stability for 2a – 2i is 2f > 2d > 2a > 2c > 2i > 2e > 2g > 2b > 2h (Table S3 and Figure 9). For the three subgroups 2a – 2c, 2d – 2f, and 2g – 2i, in which the tautomerism is caused by the hydrogen shift in the diketo group, the order of stability is: α-keto/γ-enol form > γ-keto/α-enol form > diketo form. For the other three subgroups (2a, 2d, 2g), (2b, 2e, 2h), and (2c, 2f, 2i), classified by the hydrogen shift in the triazole group, the tautomers in which the hydrogen atoms are attached to the nitrogen atom 2 were found as the most stable species. All global minima geometries of the keto-enol forms are absolutely planar, even though the triazole ring may be completely flipped one vs. the other. Still, intramolecular hydrogen bonds exist in all keto-enol species (Figure 10).

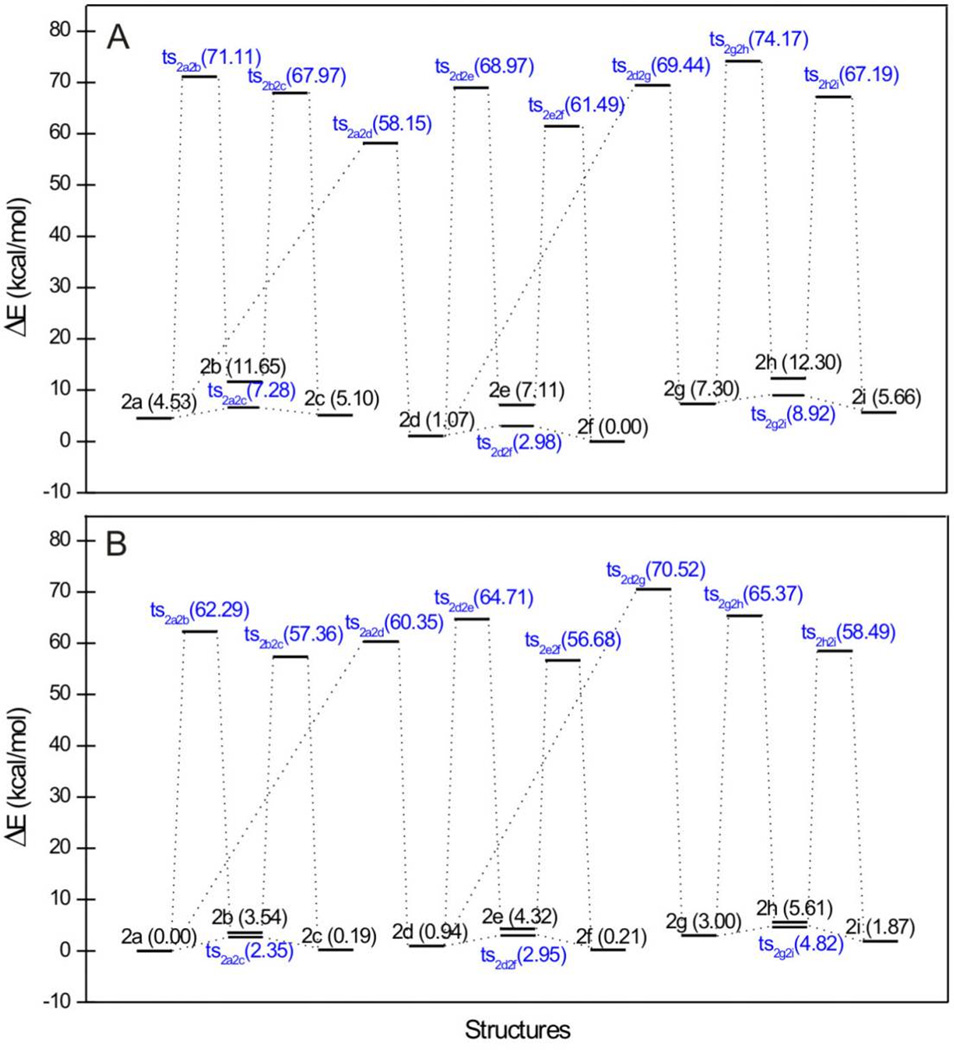

Figure 9.

Relative energies (in kcal/mol) of tautomers and their associated transition states of 2a – 2i. (A) in vacuum; (B) in aqueous solution. Values in blue are for transition structures.

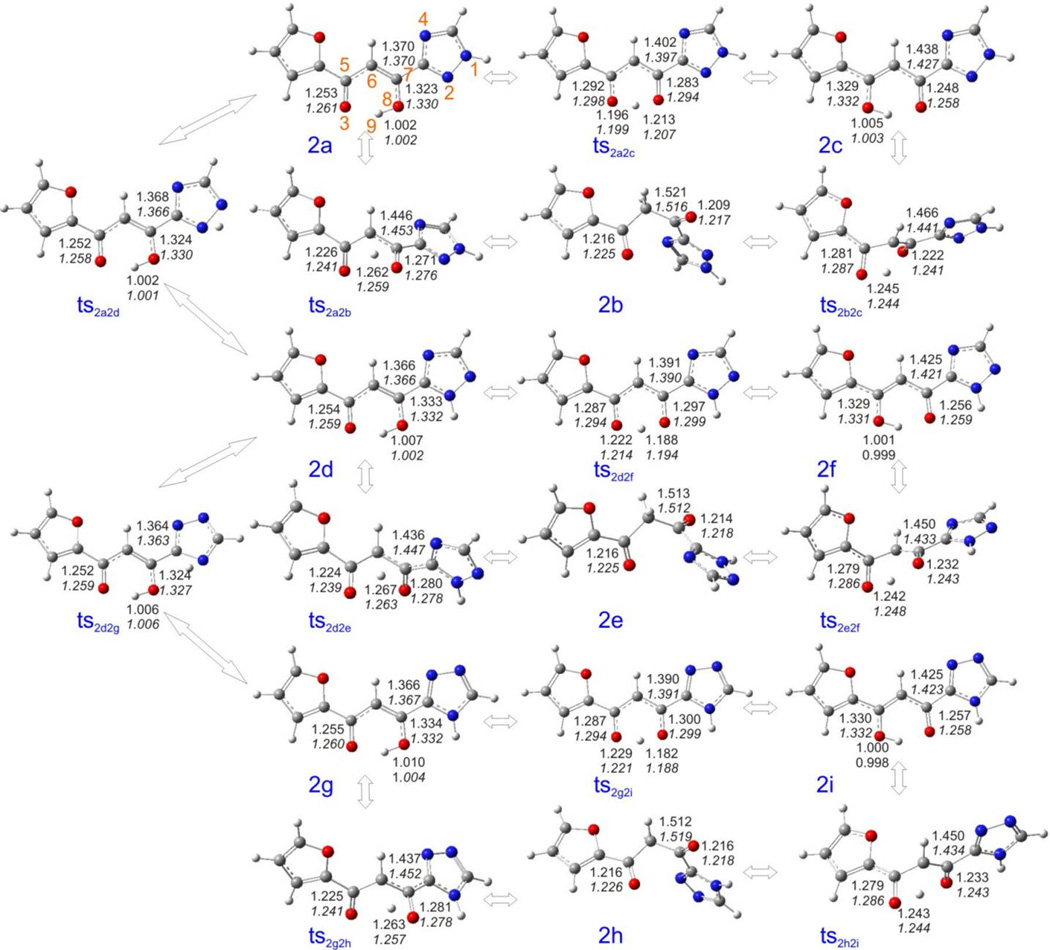

Figure 10.

Optimized geometries of 2a – 2i and their associated transition states calculated at the B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level. Upper values are the parameters in vacuum, lower values in italics are the parameters in aqueous solution.

In vacuum, we obtained eleven transition states, of which nine and two originate from the hydrogen shifts in the diketo groups and the triazole groups, respectively (Figure 9). The interconversion barriers are quite different in this group: Interconversion between the α-keto/γ-enol and α-enol/γ-keto forms are completely achievable since the energy barriers are in the range of 2.744 – 3.261 kcal/mol, whereas for those that are caused by the hydrogen shift in the diketo groups or in the triazole rings, much higher energy barriers render interconversion impossible. In the aqueous solvent model, the keto-enol species have two ionizable groups: one is the enolized hydroxyl group, which we have already discussed; the other is the triazole group, whose pKa value is about 10.[31] Based on the low acidities of these two groups, at physiological condition, the main forms of 2a – 2i are the ones without deprotonation, which therefore became the objects of our calculations. In aqueous solution, the calculated order of stability of 2a – 2i is 2a > 2c > 2f > 2d > 2i > 2g > 2b > 2e > 2h, which is different from the order in vacuum.

DFT calculations for tautomers of dihydroxypyrimidine carboxamide

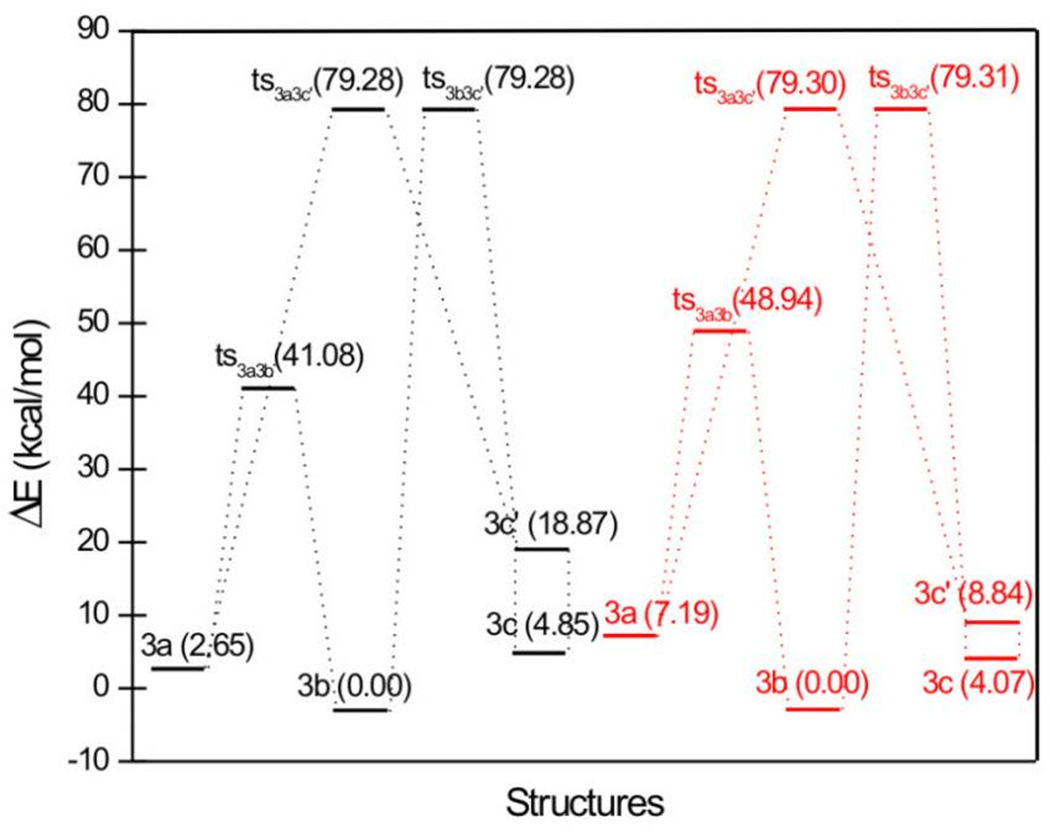

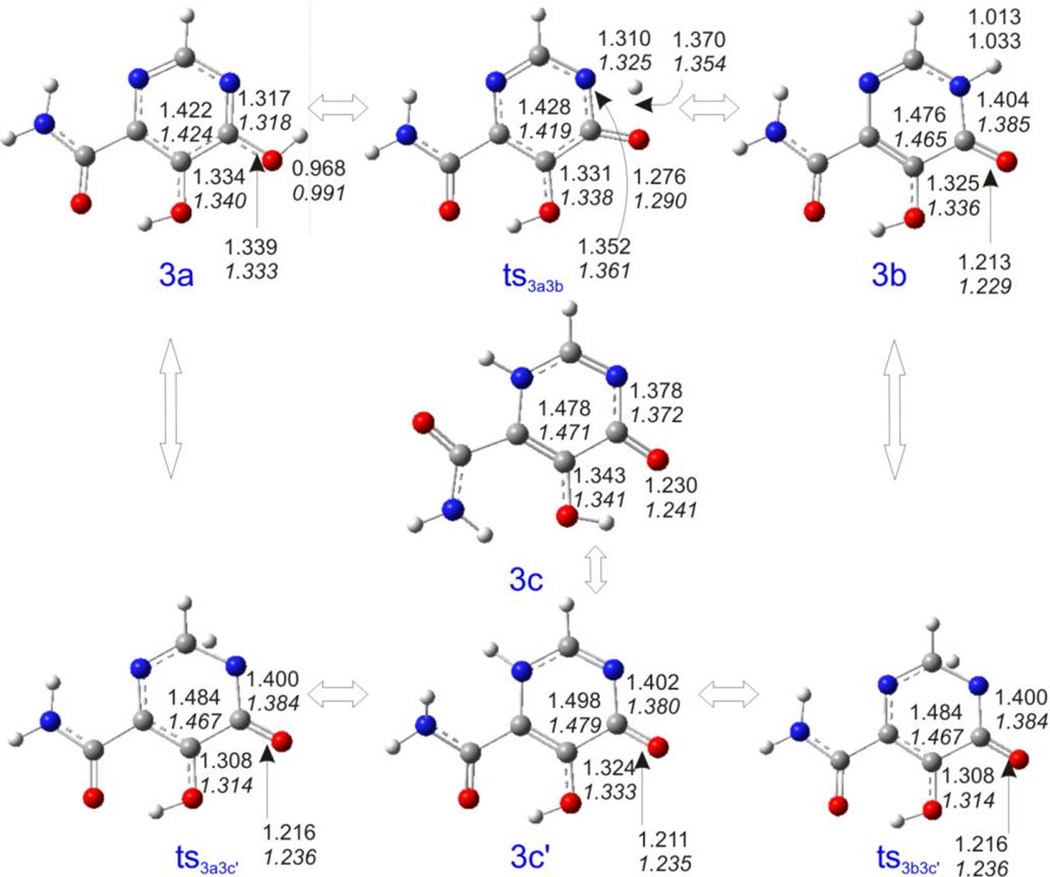

Because we did not obtain the associated transition states of 3a – 3c, we decided to use just the chelating moieties of 3a – 3c to perform the DFT calculations. To keep the nomenclature simple, we will still designate the species without the p-fluoro-benzene ring as 3a – 3c in the following. The calculated relative stability in vacuum is 3b > 3a > 3c (Table S4 and Figure 11). All global minimum structures of 3a – 3c are planar, but the one of 3c differs from the ones of 3a and 3b in the orientation of the three assumed chelating oxygen atoms (Figure 12). To more easily calculate the transition states, we used the local optimum structure 3c’, which is 14.025 kcal/mol higher in energy than 3c. It is distorted from planarity because of the intramolecular repulsion between two hydrogen atoms. Three transition states of 3a – 3c’ were obtained. It was somewhat of a surprise to find that the transition states of 3a and 3c’ and the transition states of 3b and 3c’ are totally identical to each other in each case, from both a geometric and energetic point of view. For the species calculated in aqueous solution, the order of stability is 3b > 3c > 3a > 3c’, which is different from the results in vacuum. Although the aqueous solvent increases the stability of all tautomers, the energy difference between 3a and 3b is increased nearly threefold when compared to the value in vacuum, making 3a the most unstable species in aqueous solution.

Figure 11.

Relative energies (in kcal/mol) of tautomers and their associated transition states of 3a – 3c. Black: vacuum; red: aqueous solution.

Figure 12.

Optimized geometries of 3a – 3c and their associated transition states calculated at the B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level. Upper values are the parameters in vacuum, lower values in italics are the parameters in aqueous solution.

DFT calculations for tautomers of 4-quinolone-3-carboxylic acid

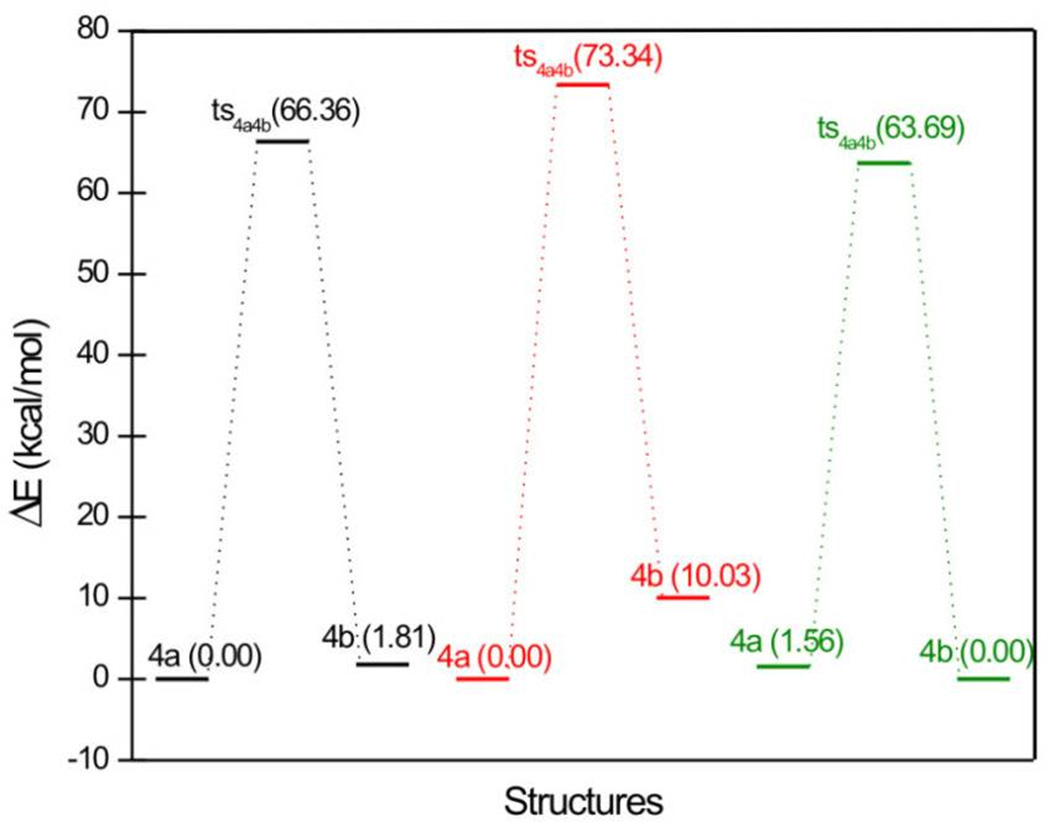

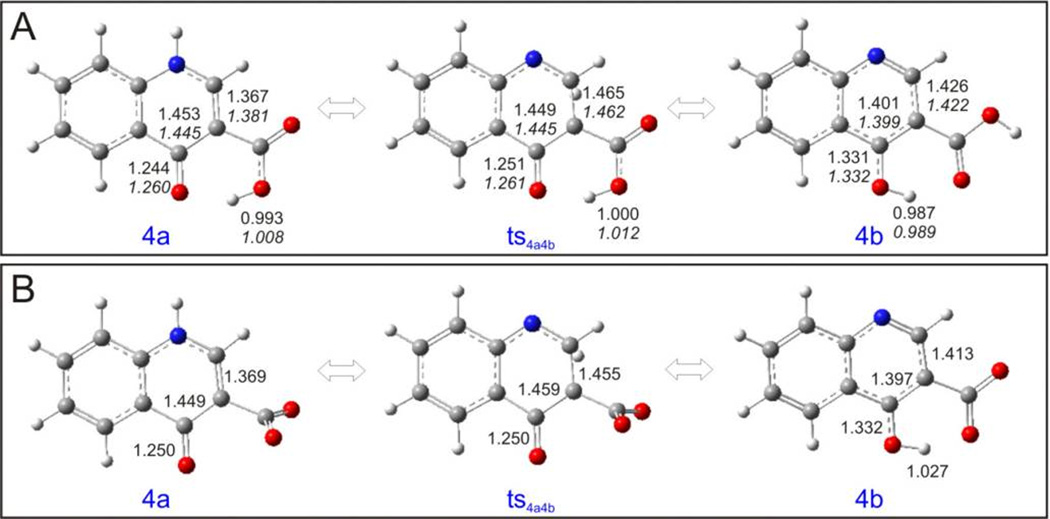

As we did not obtain the transition states of 4a and 4b, neither in vacuum nor in aqueous solution, we used the chelating moieties instead here, too. In vacuum, the more stable species is the quinolone form 4a, which has an energy only 1.809 kcal/mol lower than the quinoline form 4b, (Table S5 and Figure 13). Because of the intramolecular hydrogen bonds, involving either the hydrogen atom in the carboxylic group or the hydrogen atom in the pyridin-4-ol, both of the optimized geometries of 4a and 4b are planar (Figure 14). In aqueous solution, the order of stability of the species without deprotonation is the same as in vacuum, but the energy difference between 4a and 4b is much larger, with the result that, in aqueous solution, the main existing species would be 4a. When the carboxylic acid group is deprotonated, the situation changes: The more stable species is 4b, with a slightly lower energy than 4a (ΔE = 1.556 kcal/mol), mainly because of the formation of the intramolecular hydrogen bond in 4b.

Figure 13.

Relative energies (in kcal/mol) of tautomers and their associated transition states of 4a – 4b. Black: vacuum; red: aqueous solvent without deprotonation; green: aqueous solvent with deprotonation.

Figure 14.

Optimized geometries of 4a – 4b and their associated transition states calculated at the B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level. (A) Upper values are the parameters in vacuum, lower values in italics are the parameters in aqueous solution; (B) values in aqueous solution with deprotonated acid groups.

DFT calculation of chelation modes of α,γ-diketo acid with two magnesium ions

First, the chelating modes of the species of 1a – 1c were calculated at the B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level with only the carboxylic acid group being deprotonated. Some resulting geometric parameters of the optimized complexes are shown in Table 1 (numbering shown in Figure 15) and Figure S2. For 1a, whether in vacuum or in aqueous solution, the coordination number of either one of the two Mg2+ ions is five: In both cases, water 2 and the enolized hydroxyl group of 1a do not chelate the Mg2+ ion. The initial distances of 3.800 Å between the two Mg2+ ions shortened during the optimization to 3.495 and 3.453 Å in vacuum and in aqueous solution, respectively. Furthermore, the geometries of 1a were distorted quite heavily relative to our calculated global minima. For 1b, the coordination number for each of the two Mg2+ was six, which is the preferred number for divalent magnesium.[32] Still, the geometries of 1b were also distorted relative to the calculated global minima. For this tautomer, the distances between the two metal ions increased to more than 3.92 Å. For 1c, the chelation complex geometries seem reasonable, however 1c adopts energetically unfavorable conformations. Additionally, the optimized 1c-complex has a higher energy than either one of the 1a- and 1b-complexes. All of these findings indicate that if only the carboxylic acid group is deprotonated, the three species (1a – 1c) are not able to form good chelating complexes.

Table 1.

Absolute (in au) and relative (in kcal/mol) energies, calculated geometric parameters (in Å) for the complexes of 1a – 1c at the B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level of theory in vacuum and aqueous solution

| Complex | Energy | ΔEa | r(Mg1 – Mg2) | r(Mg1 – O1) | r(Mg1 – O2) | r(Mg2 – O2) | r(Mg2 – O3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vacuum, with both the carboxylic acid and enolized hydroxyl deprotonated | |||||||

| 1a-complex | −1960.07109 | 0.000 | 3.709 | 2.058 | 2.093 | 2.163 | 2.037 |

| 1c-complex | −1960.07109 | 0.000 | 3.709 | 2.058 | 2.094 | 2.163 | 2.037 |

| 1a-complex b | −1999.37614 | – | 3.739 | 2.066 | 2.090 | 2.208 | 2.043 |

| In vacuum, with only the carboxylic acid deprotonated | |||||||

| 1a-complex | −1960.54570 | 2.465 | 3.495 | 2.072 | 2.583 | 2.510 | 1.995 |

| 1b-complex | −1960.54963 | 0.000 | 3.936 | 2.212 | 2.213 | 2.260 | 2.093 |

| 1c-complex | −1960.53758 | 7.563 | 3.730 | 2.233 | 2.117 | 2.278 | 2.065 |

| In aqueous solution, with both the carboxylic acid and enolized hydroxyl deprotonated | |||||||

| 1a-complex | −1960.19652 | 0.000 | 3.716 | 2.068 | 2.111 | 2.165 | 2.054 |

| 1c-complex | −1960.19652 | 0.000 | 3.716 | 2.068 | 2.111 | 2.165 | 2.054 |

| 1a-complex b | −1999.49689 | – | 3.728 | 2.057 | 2.117 | 2.161 | 2.057 |

| In aqueous solution, with only the carboxylic acid deprotonated | |||||||

| 1a-complex | −1960.61471 | 8.917 | 3.453 | 2.082 | 2.491 | 2.369 | 2.024 |

| 1b-complex | −1960.62849 | 0.270 | 3.923 | 2.142 | 2.227 | 2.297 | 2.071 |

| 1c-complex | −1960.62892 | 0.000 | 3.738 | 2.222 | 2.128 | 2.259 | 2.055 |

Only systems with equal numbers of atoms are compared here;

Water molecule 3 replaced by a methanol molecule.

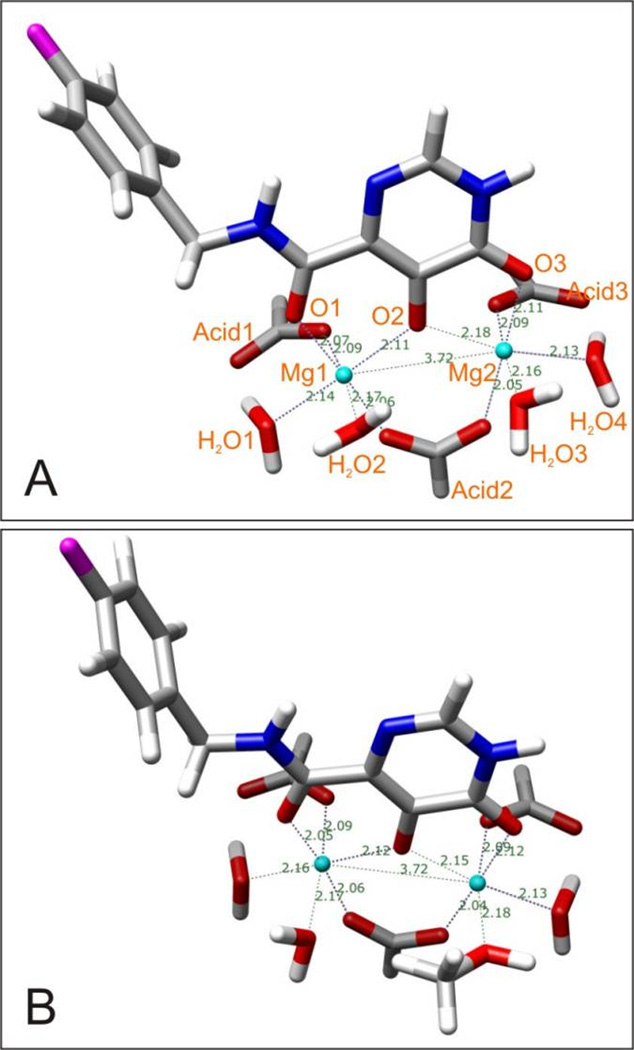

Figure 15.

Optimized geometries of 1a-complexes in aqueous solution. (A) Two Mg2+, three formic acids, four water molecules are used to partly mimic the IN binding site; (B) water molecule 3 is replaced by a methanol molecule.

As discussed above, for 1a and 1c, at physiological conditions, there are measurable quantities of the dianionic species. The presence of Mg2+ would additionally increase the probability of deprotonation of an enolized –OH group, which is corroborated by numerous X-ray crystal structures. Also, the solvent, here water, can be of fundamental importance for the deprotonation steps: several water clusters could function as proton shuttles helping in removing the protons of the –COOH and –OH groups. Based on these considerations, we assume the enolized hydroxyl groups and the carboxylic acid groups in 1a and 1c could both be easily deprotonated simultaneously when they chelate Mg2+. Our calculation results clearly support this assumption: the 1a- and 1c-complexes exhibited good chelation geometries especially in aqueous solution with an ideal coordination number of six. After optimization, the 1a-complex and 1c-complex became completely indistinguishable (Table 1). The distances between the two Mg2+ ions has shortened a little from the 3.800 Å specified in the input, to 3.709 Å (in vacuum) and 3.716 Å (in aqueous solution), maybe caused by the fact that the cationic radius for Mg2+ (0.65 Å) is less than that of Mn2+ (0.75 Å).[32] The two magnesium ions were chelated well by the three oxygen atoms in the benzoylpyruvic acid, indicated by the distances between the metal ions and the oxygen atoms, which are in the range of 2.037 ~ 2.163 Å and 2.054 ~ 2.165 Å in vacuum and in aqueous solution, respectively. However, in vacuum, the two metal ions chelated the four water molecules not so well, suggested by the calculated distances of 2.208 ~ 2.350 Å, which are larger than expected. In contrast, the PCM solvation model gave more reasonable chelating distances (2.140 ~ 2.172 Å, see Figure 15A).

Similar to the situation with Tn5 Tnp, for the IN-DNA-divalent metal complex it is generally assumed that the processed viral 3’-DNA end is bound to IN by chelation of one magnesium ion, ready to attack a host DNA phosphodiester bond.[33, 34] To simulate such a situation while keeping the resulting system tractable, we used a methanol molecule to replace water number 3. The results show that metal chelation in this complex is still well established, particularly in aqueous solution (Figure 15B): The distance between the two metal ions, each of which is at the center of an octahedron, remains at 3.728 Å; the distances between the two metal ions and their chelating oxygen atoms fall in the range of 2.057 ~ 2.170 Å. It is worthwhile to point out that the chelating conformation of 1a is planar in this environment, a geometry that is also adopted by the global energy minimum of 1a.

The experimental data show that the minimum metal-oxygen distance involving Mg2+ ions is 1.95 Å; when the coordination number is six, the average bond length is 2.08 Å.[32, 35] The crystal structure of diaquobis(acetylacetonato)-Mg2+ (Cambridge Structural Database (CSD)[36] entry ID: DACAMG; see Figure S4)[37] shows that this diketo compound is deprotonated and adopts a planar conformation when it chelates a Mg2+ ion. Comparing the geometric parameters depicted in Figure S4 with our calculated chelating distances shows that the latter are consistent with the experimental data.

DFT calculations of chelation modes of α,γ-diketotriazole with two magnesium ions

While the aforementioned considerations lead us to believe that, for the tautomers of 2a – 2i, the enolized hydroxyl groups would be deprotonated in a chelation complex with Mg2+ too, the additional question arises here about the triazole groups. From the CSD, one finds that in most cases, a 1,2,4-triazole group is not deprotonated when it chelates metal ion(s), and the preferred chelating atom is nitrogen 4 (numbering shown in Figure 10). Based on these experimental facts, complexes for 2a – 2i were submitted to DFT calculations with only the hydroxyl group being deprotonated. For the tautomers of 2a – 2c, both of the nitrogen atoms 2 and 4 of the triazole group can chelate Mg2+ ion although the preferred one is atom 4. We therefore ran calculations for both these situations. The results of the calculations are shown in Table 2 (numbering is in Figure 16), Figure S5 and Figure 16.

Table 2.

Absolute (in au) and relative (in kcal/mol) energies, calculated geometric parameters (in Å) for the complexes of 2a – 2i at the B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level of theory in vacuum and aqueous solution

| Complex | Energy | ΔE | r(Mg1 – Mg2) | r(Mg1 – O1) | r(Mg1 – O2) | r(Mg2 – O2) | r(Mg2 – N1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vacuum | |||||||

| 2a-complex | −2010.84947 | 1.113 | 3.686 | 2.081 | 2.117 | 2.189 | 2.205 |

| 2a-complexa | −2010.85124 | 0.000 | 3.695 | 2.081 | 2.108 | 2.206 | 2.190 |

| 2a-complexb | −2050.15238 | – | 3.684 | 2.084 | 2.138 | 2.164 | 2.202 |

| 2b-complex | −2011.22017 | – | 4.070 | 2.154 | 2.299 | 2.413 | 2.250 |

| 2c-complex | −2010.84947 | 1.113 | 3.686 | 2.081 | 2.117 | 2.190 | 2.206 |

| 2d-complex | −2010.84707 | 2.619 | 3.721 | 2.092 | 2.119 | 2.210 | 2.217 |

| 2e-complex | −2011.20750 | – | 4.157 | 2.174 | 2.293 | 2.500 | 2.247 |

| 2f-complex | −2010.84707 | 2.619 | 3.721 | 2.092 | 2.119 | 2.210 | 2.217 |

| 2g-complex | −2010.83328 | 11.271 | 3.728 | 2.095 | 2.133 | 2.203 | 2.206 |

| 2h-complex | −2011.20132 | – | 4.509 | 2.201 | 2.172 | 3.146 | 2.246 |

| 2i-complex | −2010.83328 | 11.271 | 3.727 | 2.095 | 2.134 | 2.202 | 2.206 |

| In aqueous solution | |||||||

| 2a-complex | −2010.92921 | 0.000 | 3.735 | 2.067 | 2.139 | 2.216 | 2.178 |

| 2a-complexa | −2010.92634 | 1.826 | 3.725 | 2.069 | 2.141 | 2.209 | 2.193 |

| 2a-complexb | −2050.23038 | – | 3.718 | 2.048 | 2.149 | 2.176 | 2.192 |

| 2b-complex | −2011.35569 | – | 4.071 | 2.136 | 2.151 | 2.596 | 2.203 |

| 2c-complex | −2010.92921 | 0.000 | 3.735 | 2.067 | 2.139 | 2.215 | 2.179 |

| 2d-complex | −2010.92636 | 1.811 | 3.746 | 2.077 | 2.145 | 2.219 | 2.180 |

| 2e-complex | −2011.33768 | – | 3.830 | 2.090 | 2.248 | 2.332 | 2.216 |

| 2f-complex | −2010.92636 | 1.811 | 3.746 | 2.077 | 2.145 | 2.219 | 2.180 |

| 2g-complex | −2010.92284 | 4.023 | 3.749 | 2.072 | 2.143 | 2.221 | 2.183 |

| 2h-complex | −2011.34232 | – | 4.041 | 2.104 | 2.193 | 2.560 | 2.195 |

| 2i-complex | −2010.92284 | 4.023 | 3.749 | 2.072 | 2.143 | 2.222 | 2.184 |

Triazole ring flipped by 180°;

Water molecule 3 replaced by a methanol molecule.

Figure 16.

Optimized geometries of 2a-complexes in aqueous solution. (A) Two Mg2+, three formic acids, four water molecules are used to partly mimic the IN binding site; (B) water molecule 3 is replaced by a methanol molecule.

The tautomers of 2b, 2e, and 2h did not form reasonable chelation complexes. The 2a-complex is impossible to tell apart from the 2c-complex after optimization. Similar situations were observed for the 2d- and 2f-complexes and the 2g-,and 2i-complexes, respectively. All of the tautomers 2a, 2c, 2d, 2f, 2g, and 2i can form plausible chelation complexes. However in terms of energy, the most stable complex in vacuum is the 2a-complex with the chelating position being nitrogen number 2 in the 1,2,4-triazole ring, whereas, in aqueous solution, the most stable one is the 2a-complex with the chelating position being 4 (Figure 16A). For the latter complex, the distance between the two magnesium ions is 3.725 Å; the distances between the two magnesium ions and the chelated oxygen atoms fall in the range of 2.069 ~ 2.174 Å; the distance between magnesium 2 and the nitrogen atom is 2.193 Å, which is consistent with the chelating distances (2.07 ~ 2.39 Å) of nitrogen atoms to magnesium found in the CSD. When water 3 was replaced with a methanol molecule, the chelation complex of 2a remained essentially intact (Figure 16B). The optimized most stable chelating conformation of 2a is planar in aqueous solution, just like the global energy minimum conformation, but the triazole ring is flipped by 180°.

DFT calculations of chelation modes of dihydroxypyrimidine carboxylate with two magnesium ions

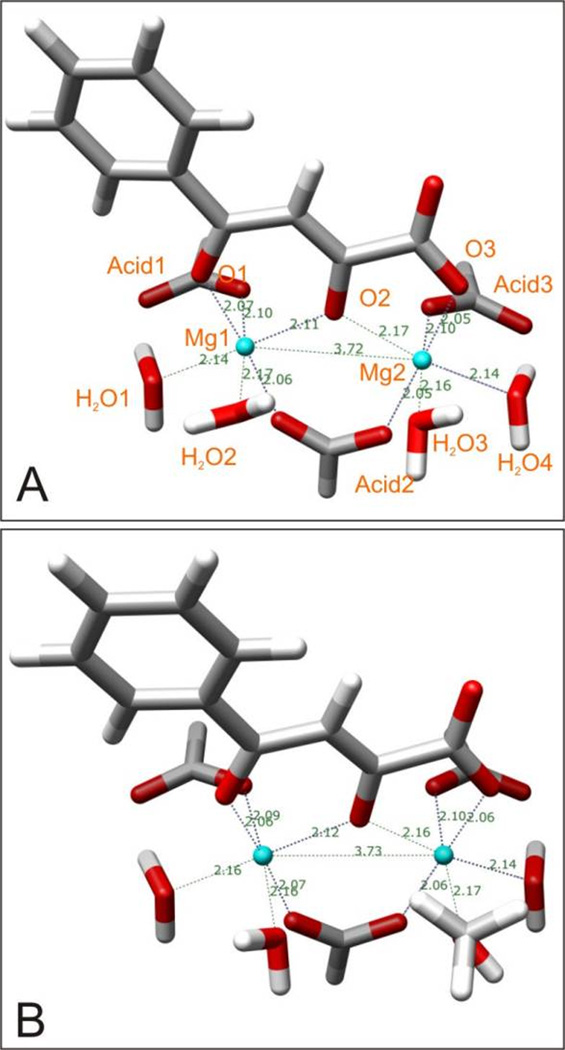

As discussed before, a phenolic hydroxyl group would most likely be deprotonated when it chelates a magnesium ion. For 3a, which has two such groups, the question arises: which one is deprotonated first? In a publication about a 5,6-dihydroxy-4-carboxypyrimidine series as inhibitors of hepatitis C virus,[38] it was reported that the phenolic hydroxyl at the C5 position has a lower pKa value (less than 7), which would lead it to be deprotonated first at physiological condition. We did not consider the possible dianionic species, therefore only the 3a-complex with one deprotonated hydroxyl group – the one at the C5 position – was submitted to the DFT calculation. The results of the calculations, both for vacuum and for aqueous solvent, are shown in Table 3 (numbering is in Figure 17), Figure S6 and Figure 17.

Table 3.

Absolute (in au) and relative (in kcal/mol) energies, calculated geometric parameters (in Å) for the complexes of 3a – 3c at the B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level of theory in vacuum and aqueous solution

| Complex | Energy | ΔE | r(Mg1 – Mg2) | r(Mg1 – O1) | r(Mg1 – O2) | r(Mg2 – O2) | r(Mg2 – O3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vacuum | |||||||

| 3a-complex | −2226.94805 | 8.734 | 3.587 | 2.109 | 2.073 | 2.107 | 2.204 |

| 3b-complex | −2226.96196 | 0.000 | 3.675 | 2.107 | 2.079 | 2.153 | 2.143 |

| 3c-complex | −2226.93512 | 16.844 | 3.667 | 2.157 | 2.084 | 2.159 | 2.098 |

| In aqueous solution | |||||||

| 3a-complex | −2227.02715 | 12.327 | 3.653 | 2.067 | 2.112 | 2.144 | 2.167 |

| 3b-complex | −2227.04680 | 0.000 | 3.715 | 2.071 | 2.107 | 2.175 | 2.109 |

| 3c-complex | −2227.03523 | 7.262 | 3.702 | 2.067 | 2.112 | 2.178 | 2.076 |

| 3b-complex a | −2266.34801 | – | 3.720 | 2.046 | 2.122 | 2.147 | 2.121 |

Water molecule 3 replaced by a methanol molecule.

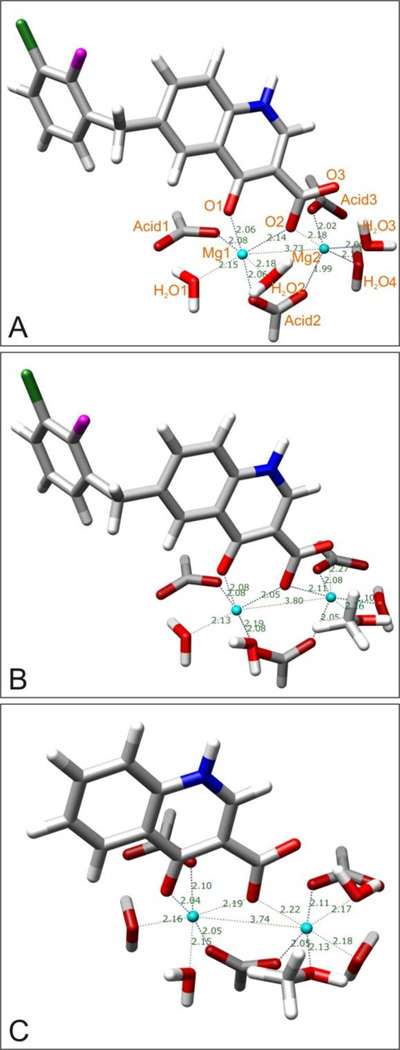

Figure 17.

Optimized geometries of 3b-complexes in aqueous solution. (A) Two Mg2+, three formic acids, four water molecules are used to partly mimic the IN binding site; (B) water molecule 3 is replaced by a methanol molecule.

Both in vacuum and in aqueous solution, these three tautomers were able to form plausible chelation complexes. In vacuum, the order of stability was 3b-complex > 3a-complex > 3c-complex, whereas in aqueous solution the order was 3b-complex > 3c-complex > 3a-complex. As for the two cases discussed above, the calculated systems in aqueous solution showed better chelating parameters than in vacuum. For the most stable complex in aqueous solution, the 3b-complex, the distance between the two magnesium ions, each of which is in the center of an octahedron, remained around 3.72 Å; the distances between the two metal ions and their chelating oxygen atoms was in the range of 2.071 ~ 2.170 Å; the chelating moiety is in a plane. When water 3 was replaced with a methanol molecule, the resulting chelating geometries showed practically no change (Figure 17).

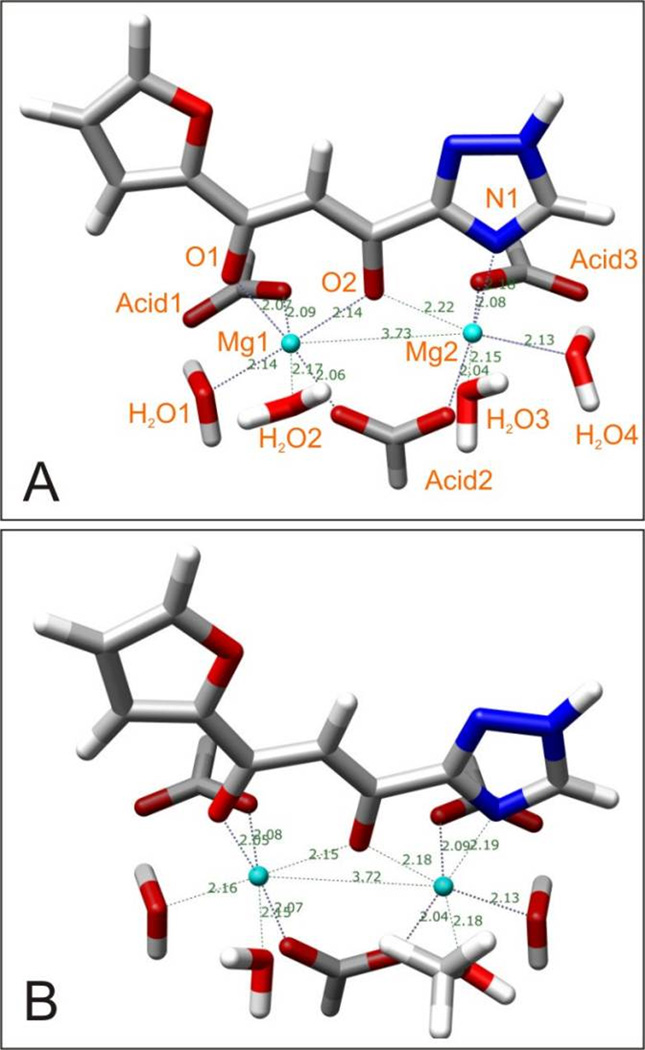

DFT calculations of chelation modes of 4-quinolone-3-carboxylic acid with two magnesium ions

The compound 4-quinolone-3-carboxylic acid would not typically be thought of as a diketo acid bioisostere, however, the 4a-complex and 4b-complex were submitted to the calculations with initial geometries in which the three oxygen atoms were placed in such a way that all of them chelated two magnesium ions each. However, the calculations did not preserve this geometry (see Table 4 (numbering is in Figure 18), Figure S7 and Figure 18).

Table 4.

Absolute (in au) and relative (in kcal/mol) energies, calculated geometric parameters (in Å) for the complexes of 4a – 4b at the B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level of theory in vacuum and aqueous solution

| Complex | Energy | ΔE | r(Mg1 – Mg2) | r(Mg1 – O1) | r(Mg1 – O2) | r(Mg2 – O2) | r(Mg2 – O3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vacuum | |||||||

| 4a-complex | −2768.83192 | 0.000 | 3.663 | 2.070 | 2.136 | 2.169 | 3.170 |

| 4b-complex | −2768.81162 | 12.743 | 3.642 | 2.167 | 2.022 | 2.115 | 2.283 |

| 4a-complex a | −2808.13441 | 0.000 | 3.748 | 2.085 | 2.049 | 2.100 | 2.368 |

| 4b-complex a | −2808.11048 | 15.015 | 3.676 | 2.185 | 2.004 | 2.130 | 2.312 |

| In aqueous solution | |||||||

| 4a-complex | −2768.90692 | 0.000 | 3.735 | 2.056 | 2.140 | 2.183 | 3.093 |

| 4b-complex | −2768.87762 | 18.387 | 3.660 | 2.193 | 2.040 | 2.118 | 2.268 |

| 4a-complex a | −2808.21882 | 0.000 | 3.799 | 2.079 | 2.049 | 2.114 | 2.274 |

| 4b-complex a | −2808.17551 | 27.175 | 3.709 | 2.204 | 2.007 | 2.138 | 2.284 |

| 4a-complex b | −2055.36305 | – | 3.744 | 2.040 | 2.187 | 2.220 | 3.164 |

Water molecule 3 replaced by a methanol molecule;

Extra water molecule added to the system, full structure of 4a replaced by only its chelating moiety (see text).

Figure 18.

Optimized geometries of 4a-complexes in aqueous solution. (A) Two Mg2+, three formic acids, four water molecules are used to partly mimic the IN binding site; (B) water molecule 3 is replaced by a methanol molecule; (C) extra water molecule added to the system, full 4a replaced by only its chelating moiety, and water molecule 3 replaced by a methanol molecule.

From an energetic point of view, the 4a-complex is more stable. In all computational environments, the coordination numbers of magnesium ion 1 stayed at six; however, for magnesium ion 2, this number changed to five: One oxygen atom of the carboxylic acid did not chelate the magnesium ion any more, causing the coordination polyhedron to become a trigonal bipyramid. Thus, compared with the diketo acid compound or its bioisosteres, 4-quinolone-3-carboxylic acid forms only three instead of four chelating bonds with the two magnesium ions.

Chen et al. have reported an X-ray crystal structure of a Mg2+ dimer of the antibacterial drug norfloxacin,[39] which is an analogue of 4a. From this crystal structure (Figure S8), one can see that only one oxygen atom of the acid group takes part in the magnesium chelation, which is fully consistent with our computational results. In this crystal structure, the distance between the two magnesium ions is 3.215 Å, which differs from the distances in our calculated systems because in this crystal structure the bridge between the two magnesium ions is different. The distances between the two metal ions and their chelating oxygen atoms in the crystal structure fall in the range of 1.996 ~ 2.085 Å, and both of the coordination numbers of the two magnesium ions are six.

To look for possible chelating modes of 4a, we added another water molecule to the calculated systems. Several jobs were submitted, but only one job ran to convergence, a system which included only the chelating moiety but not the whole molecule 4a. The optimized geometries in aqueous solution are shown in Figure 18C, from which one can see that they fit well with the reported experimental structure just discussed: Only two but not three oxygen atoms in 4a are involved in the chelation of the two Mg2+ ions, both of which show the preferred coordination number six. The distance between the two Mg2+ ions is 3.744 Å, which is almost same as the ones we calculated for diketo acid or its bioisosteres in aqueous solution.

As a backdrop to the computed chelation geometries of all the tautomers discussed in this paper, we also calculated the chelation complexes in aqueous solution of L-870,810 and MK-0518, both of which are not capable of tautomerism. We obtained the expected results, which are shown in Figure S9.

Conclusion

Use of metal chelators as therapeutic agents is becoming increasingly commonplace.[27] Several kinds of metal-chelating compounds, which are mostly derived from an α,γ-diketo acid scaffold, have been developed as antiviral agents, used as HIV-1 IN inhibitors, HIV-reverse transcriptase RNase H inhibitors, hepatitis C virus (HCV) polymerase inhibitors and influenza endonuclease inhibitors.[27] The mechanism of action of these agents almost universally appears to involve the chelation of two active site magnesium ions, typically using oxygen and/or nitrogen atoms, and thus cause inhibition.

For the specific purpose of designing moieties capable of chelating two magnesium ions that could be incorporated into HIV-1 IN inhibitors, we have investigated the tautomerism and corresponding transition states of four authentic HIV-1 IN inhibitors in this study. Our results are consistent with experimental facts and show that some tautomers can chelate the two magnesium ions very well, especially in aqueous solution.

Some of the key results we found were that, when an authentic HIV-1 IN inhibitor chelates the two magnesium ions, the distance between them stays at about 3.70 ~ 3.74 Å, and the chelating moieties adopt a planar conformation; that the hydroxyl group, which is assumed to chelate two Mg2+ simultaneously, is likely to be deprotonated allowing for a coordination number of six for each Mg2+; and when a methanol molecule replaces a water molecule, the chelating parameters in aqueous solution still remain good or become even better, suggesting that in the real binding site of IN, the terminal 3'-OH of viral DNA may be interacting with one magnesium ion via a chelating bond.

These results, which are consistent with experimental data including metal (Mg2+ and Mn2+) titration studies,[40] support the two-ion binding model for authentic HIV-1 IN inhibitors, and thus may provide detailed guidance for designing novel moieties that can be incorporated into future better inhibitors.

The detailed structural insights gained from this study have in fact already been helping us in our ongoing efforts to design better HIV-1 IN inhibitors. We, e.g., applied tautomer calculation to the novel chelating moieties identified by pharmacophore searches, and modeled complexes of such tautomers in the molecular assembly environment we presented in this paper as a model of the binding site. This includes the investigation of the two-metal chelation mechanism of more than thirty different novel scaffolds, about which we hope to be able to publish in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Megan L. Peach for her reading of, and suggestions to, this article. This study utilized the high-performance computational capabilities of the Biowulf Linux cluster at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892. (http://biowulf.nih.gov).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.chemmedchem.org: additional computational and experimental results.

References

- 1.Hazuda DJ, Felock P, Witmer M, Wolfe A, Stillmock K, Grobler JA, Espeseth A, Gabryelski L, Schleif W, Blau C, Miller MD. Science. 2000;287:646–650. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Egbertson MS. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2007;7:1251–1272. doi: 10.2174/156802607781212248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liao C, Marchand C, Burke TR, Jr, Pommier Y, Nicklaus MC. Future Med. Chem. doi: 10.4155/fmc.10.199. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Mawsawi LQ, Al-Safi RI, Neamati N. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs. 2008;13:213–225. doi: 10.1517/14728214.13.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sitzmann M, Filippov IV, Nicklaus MC. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 2008;19:1–9. doi: 10.1080/10629360701843540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asante-Appiah E, Skalka AM. Adv. Virus Res. 1999;52:351–369. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60306-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marchand C, Johnson AA, Karki RG, Pais GC, Zhang X, Cowansage K, Patel TA, Nicklaus MC, Burke TR, Jr, Pommier Y. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003;64:600–609. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.3.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grobler JA, Stillmock K, Hu B, Witmer M, Felock P, Espeseth AS, Wolfe A, Egbertson M, Bourgeois M, Melamed J, Wai JS, Young S, Vacca J, Hazuda DJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:6661–6666. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092056199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hare S, Gupta SS, Valkov E, Engelman A, Cherepanov P. Nature. 2010;464:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature08784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karki RG, Tang Y, Burke TR, Jr, Nicklaus MC. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2004;18:739–760. doi: 10.1007/s10822-005-0365-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liao C, Karki RG, Marchand C, Pommier Y, Nicklaus MC. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:5361–5365. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barreca ML, De Luca L, Iraci N, Chimirri A. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:3994–3997. doi: 10.1021/jm060323r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ason B, Knauss DJ, Balke AM, Merkel G, Skalka AM, Reznikoff WS. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2035–2043. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.5.2035-2043.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steiniger-White M, Rayment I, Reznikoff WS. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2004;14:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maignan S, Guilloteau JP, Zhou-Liu Q, Clement-Mella C, Mikol V. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;282:359–368. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pemberton IK, Buckle M, Buc H. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:1498–1506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pospisil P, Ballmer P, Scapozza L, Folkers G. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 2003;23:361–371. doi: 10.1081/rrs-120026975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brandstetter H, Grams F, Glitz D, Lang A, Huber R, Bode W, Krell HW, Engh RA. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:17405–17412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007475200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muraglia E, Kinzel O, Gardelli C, Crescenzi B, Donghi M, Ferrara M, Nizi E, Orvieto F, Pescatore G, Laufer R, Gonzalez-Paz O, Di Marco A, Fiore F, Monteagudo E, Fonsi M, Felock PJ, Rowley M, Summa V. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:861–874. doi: 10.1021/jm701164t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sato M, Motomura T, Aramaki H, Matsuda T, Yamashita M, Ito Y, Kawakami H, Matsuzaki Y, Watanabe W, Yamataka K, Ikeda S, Kodama E, Matsuoka M, Shinkai H. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:1506–1508. doi: 10.1021/jm0600139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang M, Richards WG, Grant GH. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2005;109:5198–5202. doi: 10.1021/jp045247n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belova NV, Oberhammer H, Girichev GV, Shlykov SA. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2008;112:3209–3214. doi: 10.1021/jp711290e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MOE, version 2007.09. Montreal, Quebec, Canada: Chemical Computing Group; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macromodel 9.6. New York, NY: Schrödinger, LLC; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, et al. Gaussian 03, Revision E.01. Wallingford CT: Gaussian, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams HW, Eichler E, Randall WC, Rooney CS, Cragoe EJ, Jr, Streeter KB, Schwam H, Michelson SR, Patchett AA, Taub D. J. Med. Chem. 1983;26:1196–1200. doi: 10.1021/jm00362a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirschberg T, Parrish J. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 2007;10:460–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maurin C, Bailly F, Buisine E, Vezin H, Mbemba G, Mouscadet JF, Cotelle P. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:5583–5586. doi: 10.1021/jm0408464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sechi M, Bacchi A, Carcelli M, Compari C, Duce E, Fisicaro E, Rogolino D, Gates P, Derudas M, Al-Mawsawi LQ, Neamati N. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:4248–4260. doi: 10.1021/jm060193m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aliev ZG, Shurov SN, Nekrasov DD, Podvintsev IB, Atovmyan LO. J. Stru. Chem. 2000;41:1041–1045. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woodruff M, Polya JB. Aust. J. Chem. 1975;28:1583–1587. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bock CW, Katz AK, Markham GD, Glusker JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:7360–7372. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marchand C, Zhang X, Pais GC, Cowansage K, Neamati N, Burke TR, Jr, Pommier Y. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:12596–12603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110758200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pommier Y, Johnson AA, Marchand C. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005;4:236–248. doi: 10.1038/nrd1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carrell CJ, Carrell HL, Erlebacher J, Glusker JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:8651–8656. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allen FH. Acta. Crystallogr. B. 2002;58:380–388. doi: 10.1107/s0108768102003890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morosin B. Acta. Cryst. 1967;22:315–320. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koch U, Attenni B, Malancona S, Colarusso S, Conte I, Di Filippo M, Harper S, Pacini B, Giomini C, Thomas S, Incitti I, Tomei L, De Francesco R, Altamura S, Matassa VG, Narjes F. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:1693–1705. doi: 10.1021/jm051064t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Z-F, Xiong R-G, Zuo J-L, Guo Z, You X-Z, Fun H-K. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 2000;22:4013–4014. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kawasuji T, Fuji M, Yoshinaga T, Sato A, Fujiwara T, Kiyama R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14:8420–8429. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.