Abstract

Many liness of evidence demonstrate that prostaglandins play an important role in cancer, and enhanced synthesis of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is often observed in various human malignancies often associated with poor prognosis. PGE2 synthesis is initiated with the release of arachidonic acid by phospholipase enzymes, where it is then converted into the intermediate prostaglandin prostaglandin H2 (PGH2) by members of the cyclooxygenase family. The synthesis of PGE2 from PGH2 is facilitated by three different PGE synthases, and functional PGE2 can promote tumor growth by binding to four EP receptors to activate signaling pathways that control cell proliferation, migration, apoptosis, and angiogenesis. An integral method of controlling gene expression is by posttranscriptional mechanisms that regulate mRNA stability and protein translation. Messenger RNA regulatory elements typically reside within the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of the transcript and play a critical role in targeting specific mRNAs for posttranscriptional regulation through micro-RNA (miRNA) binding and adenylate- and uridylate-rich element RNA-binding proteins. In this review, we highlight the current advances in our understanding of the impact these RNA sequence elements have upon regulating PGE2 levels. We also identify various RNA sequence elements consistently observed within the 3′UTRs of the genes involved in the PGE2 pathway, indicating these binding sites for miRNAs and RNA-binding proteins to be central regulators of PGE2 synthesis and function. These findings may provide a rationale for the development of new therapeutic approaches to control tumor growth and metastasis promoted by elevated PGE2 levels.

Keywords: Cyclooxygenase, Prostaglandin, MicroRNA, Posttranscriptional regulation, AU-rich element

1 Introduction

Prostaglandins comprise a select group of bioactive lipid messengers that play various roles in physiological and pathological processes including chronic inflammation and cancer [1, 2]. The metabolism of arachidonic acid by the cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway yields prostanoids and prostaglandin synthesis via this eicosanoid pathway can be modulated in response to a variety of cellular stimuli. Various prostanoids are generated through the COX pathway including prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), PGD2, PGF2a, PGI2, and thromboxane A2 by specific prostaglandin synthases. PGE2 is the most abundant prostanoid in human tissues and has been implicated in a variety of biological functions including maintenance of normal physiology and disease progression [3]. With regard to cancer, enhanced synthesis of PGE2 is observed in various human malignancies and is often associated with poor patient prognosis [2, 4–6]. On these grounds, it is of great importance to understand the regulation of the genes involved in the synthesis and signaling function of PGE2.

An integral method in controlling gene expression is by posttranscriptional mechanisms that regulate mRNA stability and protein translation. The impact of this level of regulation is evident as microarray analysis has detected that 40–50% of the changes in inducible gene expression occur at the level of mRNA stability [7]. Messenger RNA regulatory elements that play a critical role in identifying specific transcripts for posttranscriptional regulation typically reside within the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of the mRNA [8]. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs that have emerged as global mediators of posttranscriptional gene regulation through imperfect base pairing to the 3′UTR of its target mRNA in order to control mRNA stability and translation [9]. Currently, it is estimated that nearly 1,000 miRNAs function in humans and have been predicted to regulate approximately 60% of all protein-coding genes [10]. Another fundamental mechanism of 3′UTR-mediated posttranscriptional regulation is through association with various RNA-binding proteins that target select mRNAs containing adenylate- and uridylate (AU)-rich elements (AREs) within their 3′UTR [8]. These elements also provide target sequences for select miRNA-mediated regulation indicating the potential for crosstalk between miRNAs with 3′UTR binding proteins [11].

This review examines the contribution of 3′UTR-mediated posttranscriptional mechanisms that act to regulate numerous gene targets involved in the synthesis and action of PGE2. Through the actions of multiple miRNAs that putatively bind sequences within the 3′UTR of these genes and the presence of 3′UTR AU-rich elements, efficient regulation of PGE2 levels can be obtained. Whereas, defects occurring in the expression and function of 3′UTR trans-acting factors observed in cancer cells can be a significant contributing factor promoting PGE2 levels during tumor development.

2 Prostaglandin synthesis

Prostaglandins are formed when arachidonic acid, a 20-carbon unsaturated fatty acid, is released from the plasma membrane by members of the phospholipase A2 (PLA2) family, of which the Ca+2-dependent cytosolic PLA2 (cPLA2) plays a dominant role [12, 13]. Additionally, phospholipase C (PLC) can function in the production of free arachidonic acid through metabolism of diacylglycerol [14, 15]. Arachidonic acid is rapidly metabolized at the luminal side of nuclear and ER membranes into the intermediate PGH2 by members of the COX family through their bifunctional COX and peroxidase enzymatic activities [13, 16].

Two primary COX enzyme isoforms have been identified to play distinct roles in physiologic and pathologic conditions. COX-1 is constitutively expressed in most cell types, and COX-1-derived prostaglandins are necessary for maintaining physiological homeostasis such as protecting gastric mucosa and maintaining vascular tone [13, 16]. Normally absent in most cell types, COX-2 is an immediate early response gene that is induced in response to various proinflammatory stimuli including cytokines, growth factors, and tumor-promoting signals, resulting in increased PGE2 synthesis [13, 16]. COX-2 has been identified to play a role in the progression of tumorigenesis, supported by various reports demonstrating that COX-2 levels are increased in premalignant and malignant tumors, and this increase in COX-2 gene expression is associated with decreased cancer patient survival [2]. COX-2-derived PGE2 is the predominant prostaglandin present in solid tumors, and multiple lines of evidence demonstrate that COX-2-derived PGE2 facilitates many aspects of tumor growth as observed in studies demonstrating that treatment of PGE2 dramatically increases intestinal adenoma burden [2, 17].

The synthesis of PGE2 from COX-derived PGH2 is facilitated by three different PGE synthases (PGES): microsomal glutathione-dependent PGES (mPGES-1), microsomal glutathione-independent PGES (mPGES-2), and cytosolic PGES (cPGES) [18]. mPGES-1 is induced by cytokines and various growth factors and is coupled with COX-2 enzymatic activity, suggesting a coordinated regulation of these genes by a common factor [19, 20]. mPGES-2 is constitutively expressed but has also been shown to be induced under carcinogenic conditions and coupled to both COX isoforms [18, 21]. cPGES is constitutively expressed and is preferentially coupled to COX-1 [18, 22].

An additional mechanism involved in regulating PGE2 levels occurs through its degradation by 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (15-PGDH, HPGD) [23]. 15-PGDH is expressed in several mammalian tissues and catalyzes the rate-limiting step in the breakdown of prostaglandins [23]. Studies have highlighted the importance of this gene in PGE2 metabolism as targeted disruption of 15-PGDH has been shown to lead to increased levels of PGE2 in tissues [24]. 15-PGDH can be viewed as a functional agonist of the tumor promoting ability associated with COX-2 overexpression [25] and can serve as a functional tumor suppressor in this capacity [26–28]. Similar to other tumor suppressors, 15-PGDH expression has also been shown to be downregulated in various cancers [29–32], most likely through epigenetic silencing mechanisms [33, 34].

2.1 EP receptors

PGE2 can act in both autocrine and paracrine pathways through four specific cell surface and nuclear EP receptor subtypes termed EP1 to EP4 [1, 35]. EP receptors are rhodopsin-like seven transmembrane spanning G protein-coupled receptors primarily localized to the cell surface, although evidence exists that EP receptors can localize to the nuclear membrane [1, 36, 37]. PGE2 influences cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and invasion by activating multiple signaling cascades through EP receptors, all of which are products of four different conserved genes [38]. Although PGE2 can signal through each EP receptor, each subtype exhibits cell type-specific differences in signal transduction, localization, and regulation of expression [39]. EP1 signaling is coupled to phospholipase C/inositol triphosphate signaling, leading to the mobilization of free Ca2+ and has been implicated in upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) by signaling through extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and AKT pathways [40, 41]. EP2 and EP4 receptors are functionally similar, as signaling through both of these receptors mediates an increase in intracellular cAMP via coupling to Gs proteins [35]. The activation of EP2 and EP4 has been linked to increased β-catenin/T-cell factor transcriptional activity through inhibition of GSK-3 through various signaling cascades [42]. The EP3 receptor consists of multiple isoforms produced by alternative splicing yielding variant transcripts and has been shown to couple to both Gi and Gs proteins leading to reduced and increased cAMP levels, respectively [43, 44]. The action of PGE2 in a specific tissue etiology predominantly depends on the cell-specific EP receptor expression and the respective levels of the four receptor subtypes [38]. EP3 and EP4 receptors are the most widely represented subtypes, as one study demonstrated that expression of both receptors was detected in all tissues examined [39]. Based on observations using pharmacological antagonists and genetic deletion studies of individual EP receptors showing a decrease in tumor-progressive properties [45–47], it is of considerable interest to further understand the regulation of the transcripts encoding EP receptors in order to control their expression in cancer cells.

3 MicroRNAs

miRNAs comprise a large family of small non-coding RNAs approximately 21–24 nucleotides in length that have emerged as an integral method of posttranscriptional regulation in various cellular processes [9]. miRNAs are encoded in the genome as precursor molecules which are either transcribed from introns of protein-coding transcripts or from distinct miRNA genes. The primary miRNA transcript (pri-miRNAs) contains imperfectly base-paired hairpin structures and is processed in a stepwise manner, involving nuclear and cytosolic RNase III-type endonucleases, to produce the active form of the miRNA. In the nucleus, the Drosha endonuclease complex functions to process pri-miRNAs into hairpins of approximately 70 nucleotides, termed pre-miRNAs. These pre-miRNAs are then transported to the cytoplasm by exportin-5 where they are further processed by the endonuclease Dicer. One or both strands of the miRNA duplex generate mature miRNAs that can be loaded into the miRNA-induced silencing complex essential to miRNA-mediated gene targeting [9].

miRNAs regulate gene expression both by influencing translation and by causing degradation of target mRNAs [9], and recent findings have implicated miRNA-mediated mRNA decay to be the predominant mechanism [48]. A characteristic feature of metazoan miRNA-mediated regulation occurs through the imperfect base pairing with their mRNA target sequence [49]. Nucleotides 2–8 from the 5′-end of the miRNA comprise the essential region for miRNA targeting, termed the “seed region”, in addition to four contiguous nucleotides present at positions 13–16 from the 3′-end to significantly enhance miRNA interaction with its target mRNA [50, 51]. Recently, a class of miRNA target sites has been described that lack seed regions and 3′-compensatory pairing, but maintains contiguous base pairing in the center of the miRNA [52]. miRNAs composed of similar mature sequences are considered an miRNA family and family members may be transcribed together or independently based on their location throughout the genome. miRNAs comprising a family generally contain similar seed sequence homology and have putative target sites in many of the same genes. Approximately 30–40% of human miRNAs are organized into clusters which are loosely defined as miRNAs located <10 kb from each other. With regard to this, accumulating evidence suggests that many clustered miRNAs are transcribed as polycistrons from a single transcriptional unit, allowing for similar patterns of expression and coordinated regulation [53–56].

miRNAs have been shown to play integral roles in maintaining cellular homeostasis; however, their dysregulation has been shown to contribute to the progression, invasion, and metastasis of human cancers [57]. Current work has established the critical role miRNAs have in regulating cancer-associated gene expression and the consequences of dysregulated miRNA expression [58, 59]. More recently, genetic polymorphisms in components of miRNA networks are also being recognized as contributing factors in disease etiology [60]. Although some miRNAs can be increased, miRNA expression analysis in cancer has revealed a global repression of miRNAs in malignant tissue relative to normal tissue counterparts [61]. Various mechanisms have been identified to promote tumor-derived miRNA repression. These mechanisms range from genomic loss of miRNA loci occurring in chronic lymphocytic leukemia [62, 63] to transcriptional inhibition as observed with c-Myc-mediated repression of the DLEU2 promoter [64]. Furthermore, miRNA posttranscriptional maturation can be modulated by p53 through its interaction with the microRNA processing complex involving Drosha and p68 [65], suggesting that the common loss of p53 in tumors may contribute to decreased mature miRNA levels owing to altered miRNA processing.

By virtue of imperfect base pairing with their mRNA target sequence, each miRNA has the potential to target a large number of genes and may act concurrently to regulate multiple proteins within a specific pathway [66]. PGE2 has been well demonstrated to contribute to cancer pathogenesis, and thus coordinated regulation of the genes responsible for its synthesis and function is of great interest. This, coupled with observations demonstrating aberrant miRNA expression occurring in various human cancers [67] indicates that dysregulation of specific miRNA networks may account for increased prostaglandin production commonly seen in the progression of cancer.

In silico target prediction using RNAhybrid (http://bibiserv.techfak.uni-bielefeld.de/rnahybrid) [68, 69] and web-based microRNA prediction programs microRNA.org (www.microrna.org) [70] and MicroCosm Targets (formally miRBase targets) (www.ebi.ac.uk/enright-srv/microcosm) [71] have identified select families and clusters of miRNAs to putatively target multiple mRNA transcripts involved in PGE2 production and function (Fig. 1). Typical miRNA: target interaction is predicted based on a thermodynamic hybridization between the miRNA and target sequences to determine the energetically most favorable hybridization sites between a small RNA within a large RNA. RNAhybrid predicts that an miRNA of 22 nucleotides in length with a minimum free energy (MFE) of −25 kcal/mol for a particular binding region in a target sequence of 2 kb in length as statistically significant [68]; however, various examples of functional miRNA:mRNA target interactions have been shown to be less thermodynamically favorable. Several microRNA target prediction sites utilize local sequence complementarity to target sites with emphasis on perfect base pairing within the miRNA seed region and sequence conservation. These computational methods are valuable tools that can be used both to predict potential miRNA targets and assist in target selection for experimental validation. Utilizing these approaches, putative miRNA families and clusters have been identified to target multiple genes involved in PGE2 synthesis and function signifying their role as potential molecular switches of prostaglandin synthesis (Fig. 1). This implicates that the synthesis of PGE2 is determined by posttranscriptional regulation as well as by transcriptional mechanisms and this level of complexity is consistent with the requirement for tight control of PGE2 levels, which has pathogenic effects if levels are unregulated.

Fig. 1.

Putative microRNAs identified to regulate gene expression in the PGE2 pathway. Arachidonic acid is liberated from phospholipids by phospholipase A2 and phospholipase C activity. Free arachidonic acid can then be converted into the intermediate PGH2 by either isoform of the cyclooxygenase enzymes, COX-1, and COX-2. PGE synthases mPGES-1, mPGES-2, and cPGES can convert PGH2 into PGE2. PGE2 (green circles) can then act on the cell surface receptors EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4 in both autocrine and paracrine pathways to facilitate cellular signaling. MicroRNA target prediction reveals that members of the miR-200 family, miR-143/145, miR-101, and miR-16-1/15a have been predicted to target multiple genes involved in the generation and action of PGE2. miRNAs shown in red have been predicted using microRNA. org and MicroCosm Targets algorithms. miRNAs shown in blue were predicted to bind the respective mRNA 3′UTR using RNAhybrid using an MFE threshold of −20 kcal/mol. Functionally validated miRNAs are shown in black

3.1 miR-200 family

Numerous studies have demonstrated that malignant tissues exhibit unique miRNA expression signatures, and loss of tumor-suppressor miRNAs can contribute to cancer progression [61]. The miR-200 family comprises five mature miRNAs including miR-200a, miR-200b, miR-200c, miR-141, and miR-429 that are encoded by two separate polycistronic pri-miRNA transcripts. miR-200a, miR-200b, and miR-429 are located on Chr 1, while miR-200c and miR-141 are located on Chr 12 [72] (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the genes encoding the miR-200 family of miRNAs are located in fragile chromosomal regions and their expression has also been implicated to be epigenetically regulated, leading their expression to be frequently attenuated in various tumors [73–75]. The expression of members of the miR-200 family is depleted in aggressive tumors such as breast cancer [76], prostate cancer [77], non-small cell lung cancer [78], and meningioma brain neoplasms [79] (Fig. 3).

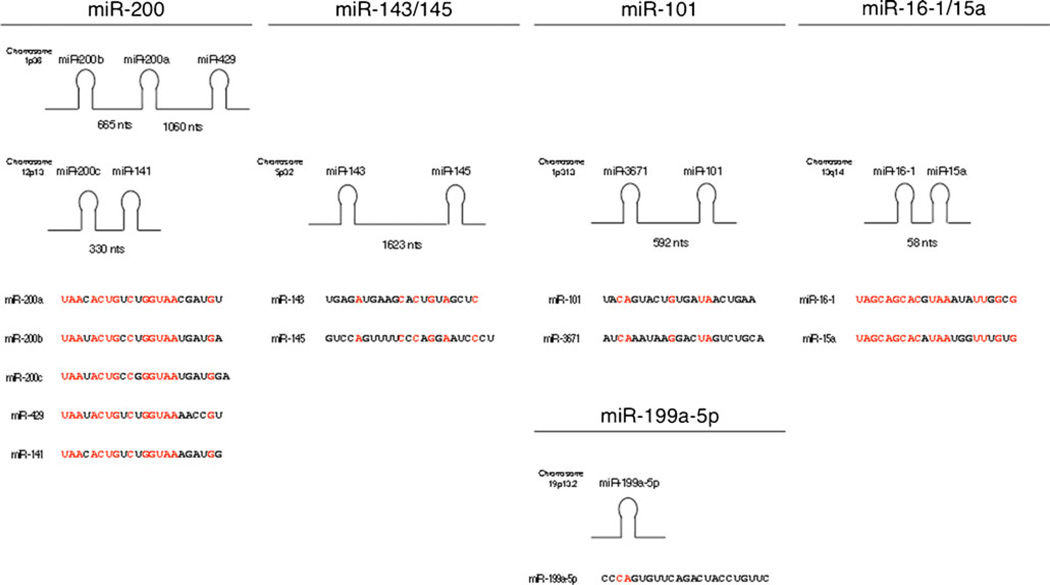

Fig. 2.

MicroRNA sequences and location of miR-200 family, miR-143/145, miR-101, and miR-16-1/15a. miRNA families consist of miRNAs with similar mature sequences and are either transcribed together as part of a polycistronic pri-miRNA or are located at distinct sites throughout the genome. The chromosomal location and distance between clustered miRNAs of the four classes of miRNAs identified to target the genes that mediate PGE2 synthesis and function are indicated. In the mature miRNA sequences, red text indicates regions of sequence homology within each miRNA family. MiR-3671 is located approximately 600 nucleotides upstream of miR-101; however, miR-3671 has not been validated to be co-expressed with miR-101 or was identified to target any genes in the PGE2 pathway

Fig. 3.

The expression of miRNAs identified to regulate the PGE2 pathway are attenuated in various types of cancer

This family of miRNAs has been shown to mediate various tumorigenic processes such as tumor cell adhesion, migration, invasion, metastasis, and its role in epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) is well established. In EMT, miR-200 family members directly target the E-cadherin transcriptional repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2 and loss of miR-200 results in decreased E-cadherin expression allowing for increased invasive and migratory properties [80, 81]. The tumor-suppressive role of miR-200 has been further established by studies that show all members of the miR-200 family regulate epidermal growth factor (EGF)-driven cancer cell invasion [82]. Interestingly, at least one member of the miR-200 family putatively targets all genes involved in PGE2 synthesis and function, and PLC (PLCG1) is an established target of miR-200b, miR-200c, and miR-429 [82] (Fig. 1). PGE2 has also been shown to exert its pro-tumorigenic effects through EGF, as induced migration and invasion through PGE2 occurs via rapid transactivation and phosphorylation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [83]. Overexpression of miR-200 in cancer cells has also been shown to increase sensitivity to EGFR-targeted therapy and decrease cell invasion in the presence of EGF, indicating a potential concerted effort of miR-200 to regulate prostaglandin synthesis and EGFR activity [82, 84].

3.2 miR-143/145

Both miR-143 and miR-145 are located on Chr 5q32 and are thought to originate from the same primary miRNA transcript (Fig. 2); however, some studies have suggested tissue-specific transcriptional regulation may account for their independent regulation [85–88]. The expression of miR-143 and miR-145 are attenuated at the adenoma and carcinoma stages of colorectal cancer [89] and are consistently attenuated miRNAs in colorectal tumors and cell lines [90–92]. Similarly, both miRNAs have been observed to be reduced in prostate cancer [93], esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [88], osteosarcoma [94], bladder urothelial cancer [95], and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and B cell lymphomas [96] (Fig. 3). Furthermore, reintroduction of miR-143 and miR-145 into various cancer cell lines has been shown to repress abnormal cell growth and proliferation [90, 96–99]. This growth inhibitory effect is suggested to be attributed to the posttranscriptional decrease of target genes, insulin receptor substrate-1 [100] and c-myc [98] by miR-145 and Erk5 [101] and KRAS [99] by miR-143. To further support the role of miR-145 in controlling cell growth, recent studies have found that miR-145 expression increases throughout embryonic stem cell differentiation to directly target the pluripotency factors OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4 [85]. Interestingly, OCT4 is also expressed in adult cancer stem cell-like cells [102], suggesting that tumor-derived loss of miR-145 to be a component of cancer stem cell maintenance. Additional support for the tumor-suppressive role of miR-145 reveals that the upregulation of miR-145 represses OCT4 to induce differentiation in endometrial cancer cells and subsequently inhibits tumor growth [103].

miR-145 has also been implicated as a potential component of 5q- syndrome, a myelodysplastic disorder of hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) [104]. miR-145 maps to a chromosomal region commonly deleted in this disorder, and individuals with 5q- syndrome display attenuated miR-145 levels. Knockdown of miR-145 in HSCs correlated with thrombocytosis, a feature that often occurs in tandem with various inflammatory diseases [105]. Interestingly, miR-145 was identified to target every single gene involved in PGE2 synthesis and function examined in this study, and miR-143 potentially regulates approximately 65% of them (Fig. 1), indicating that deletion of miR-143/145 may initiate the inflammatory process in individuals with 5q-syndrome through dysregulation of PGE2 synthesis and function. Of particular interest, in silico target prediction reveals that miR-145 putatively targets some of these transcripts with the strongest binding affinities observed including COX-1 (−31 kcal/mol), mPGES-1 (−32 kcal/mol), and mPGES-2 (−34 kcal/mol).

In a study examining the physiological consequences of miR-143/145 deletion in mice, vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) were found to be more migratory and displayed increased cell proliferation [106]. Aberrant proliferation of SMCs plays a key role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, and it is postulated that dysregulation of miR-143/145 underlies the histological changes observed in vascular disease [106]. The mechanisms by which these miRNAs regulate VSMC motility have not been determined; however, PGE2 has been shown to stimulate VSMC proliferation [107], and miR-143/145 may mediate this process by regulating the genes involved in prostaglandin synthesis and function.

3.3 miR-101

Loss of microRNA-101 (miR-101) expression was first discovered in a prostate cancer study that identified the genomic loci encoding miR-101 (located on Chr 1p31.3) to be lost in 67% of metastatic cells [108]. Since this first report, miR-101 has further been shown to be attenuated in a variety of malignant tissues including colon cancer [109], prostate cancer [77], non-small cell lung cancer [110], glioblastoma [111], hepatocellular cancer [112], and bladder cancer [113] (Fig. 3). Investigation into the mechanistic role of miR-101 has shown that this miRNA directly targets the polycomb group protein EZH2, a component of a histone methyltransferase shown to silence tumor suppressor genes in cancer [113]. Furthermore, ectopic expression of miR-101 has been shown to significantly inhibit cellular proliferation, migration, and invasion in multiple cancer cell lines [113, 114].

In addition to targeting EZH2, miR-101 putatively targets multiple genes involved in the PGE2 pathway and has been shown to directly target and translationally suppress COX-2 (Fig. 1). miR-101 was shown to be involved in COX-2 regulation during embryo implantation [115] and its expression has been shown to be inversely correlated with COX-2 overexpression in endometrial cancer cells [116]. More recently, COX-2 has been identified as a direct target of miR-101, and loss of miR-101 correlates with high levels of COX-2 protein in both tissues and metastases from colorectal cancer patients [109]. COX-2 is overexpressed in approximately 80% of colorectal adenocarcinomas and has been shown to play roles in invasiveness, apoptotic resistance, and increased tumor angiogenesis through its major end product PGE2 [117]. COX-2 has been shown to promote an angiogenic switch by increasing the production of angiogenic factors such as VEGF [118]. Another study found that overexpression of miR-101 in angiogenic endothelial cells shifted cells to a more stationary phenotype due to inhibition of EZH2 [111], and enhanced expression of miR-101 may also contribute to this phenotype due to attenuated PGE2 production by inhibition of COX-2. miR-101 may also modulate the expression of other key players involved in PGE2 synthesis (Fig. 1), indicating miR-101 as a potential regulator of aberrant prostaglandin production seen in colorectal cancer. It is also of interest that miR-199a-5p (previously designated miR-199a*) was additionally identified in studies to regulate COX-2 [115, 116]. Moreover, miRNA prediction analysis reveals that miR-199a-5p putatively targets COX-1 suggesting a potential role of miR-199a-5p in PGE2 regulation via regulation of cyclooxygenase activity.

3.4 miR-16-1 and miR-15a

Due to the distinctive miRNA expression profiles in cancer, it is postulated that upregulated miRNAs can act as oncogenes, and downregulated miRNAs can act as tumor suppressors. The first report implicating a role for miRNAs in cancer progression examined miR-16-1 and its function in CLL [62]. This miRNA is clustered with miR-15a and located in the most commonly deleted genomic region of individuals affected by CLL who display attenuated expression of miR-16-1 and miR-15a [62] [119]. Additionally, the deletion of the miR-16-1/15a cluster in mice causes development of B cell lymphoproliferative disorders, recapitulating the CLL phenotype observed in humans [120]. It was determined that the loss of miR-16-1 and miR-15a promotes cell survival, as they function to target and repress anti-apoptotic factors BCL-2 and MCL1, genes that are overexpressed in numerous cancers and have been shown to favor survival by inhibiting cell death [121, 122]. miR-16-1 in particular has additionally been shown to play a role in cell cycle maintenance through regulation of several cell cycle regulatory genes [123]. These results are in agreement with those showing reduced miR-16-1 levels present in the colorectal microRNAome [124] along with other cancers including prostate cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, and pituitary adenomas [61, 125–127] (Fig. 3).

In addition to housing miRNA binding sites, the 3′UTR of select mRNAs contain AU-rich cis-acting elements (AREs) that mediate the stability of the mRNA transcript [128], and miR-16-1 has been shown to contain sequence homology to AREs. A work by Jing et al. identified the ability of miR-16 to promote degradation of ARE-containing transcripts, and the ARE-complementary sequence within miR-16 was required for mRNA decay through base pairing between miR-16 and the ARE that was independent of miRNA 5′ seed sequence complementarity [49, 129]. Other studies have validated miR-16-1 targeting of the COX-2 3′UTR in work examining COX-2 3′ UTR-mediated posttranscriptional regulation by miR-16-1 in response to diabetic stimuli in leukocytes [130].

Due to miR-16-1′s unique sequence complementarity to AREs, it has been shown to functionally interact with various RNA binding proteins involved with mediating ARE-containing mRNA decay. miR-16-1 has been shown to work in conjunction with the mRNA-destabilizing factor tristetraprolin (TTP) to promote rapid decay of ARE-containing mRNAs through interaction with components of the RISC complex [129]. Additionally, miR-16-1 has been implicated to repress translation of the mRNA stability factor Hu antigen R (HuR) transcript and loss of miR-16-1 in breast cancer was correlated with HuR overexpression [131], further emphasizing the dynamic role of this ARE-targeting miRNA. Interestingly, all but two genes essential for PGE2 synthesis and function contain putative AREs within their 3′UTR (Fig. 4) and are potential targets of miR-16-1. The presence of these elements may indicate a conserved role of both miRNA and RNA-binding protein-mediated regulation of this biological pathway.

Fig. 4.

Presence of 3′UTR AU-rich elements in prostaglandin pathway transcripts. The representation of the human mRNAs is not to scale. The filled triangles represent AU-rich sequences, AUUUA, contained within the 3′UTR; triangles adjacent to one another indicate multiple repeat elements. Identification of AU-rich elements was accomplished with AREsite (rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/AREsite.cgi) [143] using the representative transcript containing the greatest number of AUUUA motifs although polyadenylation and splice variants can yield shortened 3′UTRs as observed with COX-1, COX-2, and EP3 mRNAs

3.5 miR-21

In contrast to the observed loss of miRNA expression in tumors discussed above, miR-21 is the only miRNA known to date to be upregulated in all human cancers [132, 133]. A large amount of experimental data has demonstrated that overexpression of miR-21 impacts various aspects of tumorigenesis including tumor cell proliferation, evasion of apoptosis, and invasion and metastasis [132]. Furthermore, inhibition of miR-21 can lead to cell cycle arrest, increased apoptosis, and sensitivity to anticancer agents [132]. The ability of miR-21 to function as an oncomiR is evident in human cancer, as miR-21 overexpression is significantly associated with tumor aggressiveness and poor patient survival [133–137].

As various oncogenic pathways are influenced by miR-21 overexpression [132], it is conceivable that miR-21 would promote enhanced levels of PGE2 in tumors. To this extent, microRNA target prediction identifies 15-PGDH as a putative target of miR-21-mediated regulation. MicroRNA. org and MicroCosm predict two distinct target sites for miR-21 within the 15-PGDH 3′UTR, with MFEs of −19.0 and −17.3 kcal/mol. Additionally, in silico target prediction using RNAhybrid identifies a third distinct putative binding region for miR-21 within the 3′UTR with a MFE of −19.7 kcal/mol. This suggests that miR-21 coordinately targets 15-PGDH mRNA in order to contribute to PGE2 accumulation in the tumor microenvironment. In agreement with this, 15-PGDH is not predicted to be regulated by any of the other miRNAs highlighted in this review; however, cPLA2 was the only other gene in the prostaglandin pathway identified by MicroCosm to be a putative miR-21 target although a predicted MFE of −10.5 kcal/mol was determined for this binding site.

4 AU-rich 3′UTR elements

Messenger RNA turnover is a highly regulated process that plays a central role in the regulation of mammalian gene expression and the control of mRNA decay allows a cell to rapidly respond to changes occurring through intracellular and extracellular signals [8]. Eukaryotic mRNAs contain two characteristic features that are integral to their function, a 5′ 7-methylguanosine cap and a 3′ poly(A) tail. In mammalian cells, the majority of mRNA decay is initiated by shortening of the poly(A) tail (deadenylation). At this point, degradation initiating at the 5′ end involves removal of the 5′ cap by decapping enzymes, followed by 5′ to 3′ exonucleolytic decay. Alternatively, the mRNA can be degraded by 3′ to 5′ exonucleolytic degradation through a complex of exonucleases known as the exosome [8]. These two decay pathways are not mutually exclusive and there appears to be overlap between the pathways, although the relative contribution of each mechanism is under debate [8, 138]. Many of these mRNAs targeted for degradation are localized to processing (P)-bodies, which are small cytoplasmic foci that contain components of both 3′ to 5′ and 5′ to 3′ decay machinery, suggesting these decay pathways converge at P-bodies [8, 139]. An alternative fate of mRNAs observed under situations of cellular stress is their trafficking to cytoplasmic stress granules where they are translationally silenced. Current work now indicates a functional interaction between P-bodies and stress granules suggesting that mRNAs destined for decay are sorted at stress granules and delivered to P-bodies for degradation [140].

A characteristic cis-acting mRNA element controlling the expression of many inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and proto-oncogenes is the AU-rich element, or ARE [141]. The functional ARE is present within the mRNA 3′UTR and is most often composed of copies of an AUUUA sequence motif. AREs are organized into several classes and clusters on the basis of the number and context of the AUUUA pentamer as observed in various immediate early response genes (e.g., proto-oncogenes) that bear scattered repeats of the AUUUA motif versus mRNAs encoding inflammatory mediators and cytokines (e.g., COX-2) that have multiple repeats of the AUUUA pentamer clustered together [141, 142]. Using the AREsite (rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/AREsite.cgi) online resource for investigating AREs in vertebrate mRNA 3′UTR sequences [143], the presence of this 3′UTR element was observed in a majority of PGE2 pathway genes (Fig. 4). This is consistent with estimates indicating that approximately 16% of human protein coding genes contain an ARE sequence within their 3′UTR [143], highlighting its significance in posttranscriptional gene regulation.

The role of ARE-mediated posttranscriptional regulation is best studied in COX-2 regulation [144, 145]. Within the COX-2 3′UTR, a 116 nucleotide region containing a cluster of six AUUUA sequence elements located near the stop codon of COX-2 serves as the functional ARE [146]. Posttranscriptional regulation has been shown to be dependent upon this ARE since its presence confers rapid decay of a normally stable reporter mRNA [146]. Furthermore, this AU-rich region is highly conserved in both sequence and location among various species of COX-2, implying that ARE function has been evolutionary conserved [147]. Similar to COX-2, the presence of 3 AUUUA motifs in the cPLA2 3′UTR was demonstrated to exert an mRNA-destabilizing effect on cPLA2 [148, 149]. Evidence of posttranscriptional regulation was also observed with regulation of PLC expression during PMA-induced promyelocytic cell differentiation [150], although it is not known if this effect was dependent of the PLC 3′UTR.

4.1 ARE-binding proteins

AREs mediate their regulatory function through the association of trans-acting RNA-binding proteins that display high affinity for AREs. The best studied ARE-binding proteins can promote rapid mRNA decay, mRNA stabilization, or translational silencing [8]. Through these mechanisms, ARE-binding proteins exhibit pleiotropic effects on gene expression, since a single ARE-binding protein can bind to multiple mRNAs and binding can occur among different classes of AREs [128, 141]. Various cytoplasmic proteins have been detected to bind AREs and work focused on identifying and characterizing COX-2 ARE-binding proteins provides a focal point of regulation that may be extended to other genes in the PGE2 pathway. To date, 16 different RNA-binding proteins have been reported to bind the COX-2 3′UTR [145]. This review will focus on the most well-documented RNA-binding proteins that regulate COX-2 expression and their potential impact on cancer (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

ARE-binding proteins mediating posttranscriptional the regulation of COX-2. COX-2 expression is tightly regulated at the posttranscriptional level by RNA-binding proteins that promote mRNA stability (HuR, CUGBP2, and RBM3), mRNA decay (TTP), and translational inhibition (TIA-1 and CUGBP2) through their binding of the COX-2 AU-rich element (ARE)

4.1.1 HuR (ELAVL1)

The HuR protein is an ubiquitously expressed member of the embryonic lethal abnormal vision (in Drosophila) family of RNA-binding proteins [151]. The human Hu proteins (ubiquitously expressed HuR and neuronal-specific HuB, HuC, and HuD) were originally discovered as antigens in patients displaying paraneoplastic disorders such as cerebellar carcinoma and are used as biomarkers for paraneoplastic syndromes [152, 153]. The cloning and characterization of HuR demonstrated that HuR contains three RNA recognition motifs (RRM) with high affinity and specificity for AREs and that overexpression of HuR stabilizes ARE-containing transcripts and promotes their translation [151].

The ability of HuR to function as an ARE stability factor appears to be linked to its subcellular localization [154]. HuR is localized predominantly in the nucleus (>90%) and can shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm. It is hypothesized that the ability of HuR to promote mRNA stabilization requires its translocation to the cytoplasm, and overexpression of HuR promotes cytoplasmic localization where it binds target ARE-containing mRNAs and interferes with their rapid decay [151, 154]. A variety of cellular signals known to activate MAPK pathways involving p38 and ERK kinases, the PI-3-kinase pathway, and the Wnt signaling pathway have been shown to trigger cytoplasmic HuR localization and promote ARE-containing mRNA stabilization [155–157]. Insight into the mechanism of HuR-mediated mRNA stabilization has been advanced with the identification of low molecular weight inhibitors for HuR [158]. These compounds interfere with the formation of HuR dimers and RNA binding, indicating that HuR homodimerizes prior to ARE binding. Furthermore, these compounds inhibit HuR cytoplasmic localization, suggesting that an HuR dimer is the active species involved in nucleocytoplasmic trafficking [158].

HuR has been shown to associate and posttranscriptionally regulate the expression of numerous cancer-associated transcripts bearing AREs of multiple classes [159, 160]. Based on its ability to bind the COX-2 ARE region consisting of a highly conserved cluster of 6 AUUUA elements located near the stop codon, HuR has been identified as a trans-acting factor involved in regulating COX-2 expression [161]. The enhanced stabilization of COX-2 mRNA observed in colon cancer cells is, in part, due to elevated levels of HuR [161, 162]. Recent work evaluating HuR expression in colon cancer demonstrates that HuR is expressed at low levels and is localized to the nucleus in normal tissue, whereas HuR overexpression and cytoplasmic localization were observed in colon adenomas, adenocarcinomas, and metastases [162]. Furthermore, several studies indicate that HuR overexpression and cytoplasmic localization are markers for elevated COX-2 that is correlated with advancing stages of various cancers and poor clinical outcome [147]. mPGES-1 has also been identified as a direct target of HuR [163], suggesting HuR to play a distinct regulatory role in PGE2 synthesis through its interaction with COX-2 and mPGES-1 mRNAs and potentially other ARE-containing genes involved in PGE2 synthesis (Fig. 4).

4.1.2 CUGBP2

CUG triplet repeat-binding protein 2 (CUGBP2) is an ubiquitously expressed RNA-binding protein containing three RNA recognition motifs and is a member of the CUGBP-ETR-3-like factors family [164, 165]. Work investigating COX-2 regulation in colon cancer cells and intestinal epithelium subjected to ionizing radiation determined that CUGBP2 regulated the expression of COX-2 and other ARE-containing genes on a posttranscriptional level [164, 165]. CUGPB2 displays high affinity for the COX-2 ARE and radiation-induced overexpression of CUGBP2 led to COX-2 mRNA stabilization similar to the overexpression of HuR protein [164]. However, in contrast to HuR, CUGBP2 repressed COX-2 translation by inhibition of ribosome loading of the COX-2 mRNA [164]. Given that HuR enhances and CUGBP2 inhibits COX-2 protein expression, this indicates that these two ARE-binding proteins differ in their regulation of COX-2 mRNA translation. Although both proteins have similar affinities for the COX-2 ARE, CUGBP2 was effective in competing with HuR for ARE-binding leading to a translational block in COX-2 expression [166]. While demonstrating the ability of CUGBP2 to regulate the opposing functions of COX-2 mRNA stabilization and translational repression, these findings indicate a role for CUGBP2 in the early stages of tumorigenesis by regulating PGE2 levels through repression of COX-2 protein synthesis.

4.1.3 RBM3

RNA-binding motif protein 3 (RBM3) is a translational regulatory factor consisting of a single RRM domain and a glycine-rich region [167, 168]. Its role in COX-2 regulation was initially identified through its binding to the AU-rich elements in the murine COX-2 3′UTR [169], and two hybrid screening analysis identified RBM3 to interact with HuR [170]. Similar to HuR expression in cancer, RBM3 is significantly upregulated in colorectal tumors and overexpression of RBM3 in fibroblasts promoted cell transformation [171], indicating an oncogenic capacity for this RNA-binding protein.

Consistent with its interaction with HuR, RBM3 is also nucleocytoplasmic-shuttling protein that promotes stabilization of COX-2 mRNA through binding to ARE sequences located in the first 60 nts of the COX-2 3′UTR [171]. This ability to stabilize ARE-containing transcripts was also observed with VEGF and IL-8 mRNAs. RBM3 protein also promotes translation of COX-2 mRNA through its 3′UTR [171]; however, the mechanism underlying this effect and RBM3’s partnership with HuR to promote COX-2 mRNA translation remains to be determined. Through its ability to promote mRNA stability and translation of otherwise rapidly degraded transcripts, RBM3 is being recognized as a contributing factor promoting enhanced PGE2 levels during tumorigenesis.

4.1.4 TTP, ZFP36, TIS11)

TTP is a member of a small family of tandem Cys3His zinc finger proteins consisting of TTP, ZFP36L1, and ZFP36L2 [172, 173]. TTP acts on a posttranscriptional level to promote rapid decay of ARE-containing mRNAs by direct ARE binding [174]. The binding of TTP to AREs targets the transcript for rapid degradation through association with various decay enzymes [175–180]. In cells, TTP localizes to P-bodies [181], which suggests that TTP plays a critical role in ARE–mRNA delivery to cytoplasmic sites of mRNA decay [181, 182]. TTP is also a target of phosphorylation by various pathways, and this phosphorylation state likely plays a role in mediating TTP function [173].

Based on the severe inflammatory phenotype of TTP knockout mice [183], efforts to identify ARE-containing targets of TTP have focused on inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α and GM-CSF [175, 184], and a recent work has shown COX-2 to be a target of TTP [162, 185]. With regard to its role in controlling COX-2 expression in cancer, a consistent loss of TTP expression occurs in a variety of human cancers such as breast, colon, cervix, prostate, and lung [162, 186, 187], and suppressed TTP expression can serve as a negative prognostic indicator in breast cancer [186].

TTP preferentially binds the nonameric sequence motif, UUAUUUAUU, the core-destabilizing element of many ARE-containing mRNAs [188, 189]. Interestingly, nonameric sequences are the second most abundant motif present in genes involved in the PGE2 pathway, indicating that these transcripts are likely targets of TTP-mediated regulation. These findings indicate that the presence of TTP in normal tissues serves a protective role by controlling expression of various pro-inflammatory and prostaglandin synthesis mediators, whereas loss of TTP expression in cancer allows for the stabilization and overexpression of these transcripts.

4.1.5 TIA-1

T cell intracellular antigen 1 (TIA-1) was originally identified in activated T lymphocytes and is an RNA-binding protein containing three RRM motifs with specificity to mRNAs containing short sections of uridylate repeats [190, 191]. Under normal cellular conditions, this protein is predominantly nuclear, and in response to cellular stress, translocates to the cytoplasm where it is associated with untranslated mRNAs in discrete cytoplasmic stress granules, implicating a role in translational regulation [140, 181]. TIA-1 has been shown to bind the COX-2 ARE and regulate its expression through translational inhibition without altering COX-2 mRNA turnover [192]. Whereas in colon cancer cells, deficiencies in TIA-1 binding to the COX-2 ARE were observed, allowing for increased polysome association with the COX-2 mRNA. This regulation of COX-2 expression was also observed in TIA-1-deficient fibroblasts that produce significantly more COX-2 protein and PGE2 than wild-type fibroblasts. In vivo, TIA-1 knockout mice maintain elevated levels of COX-2 leading to the development of arthritis [193]. These findings implicate TIA-1 as a translational silencer of COX-2 expression and suggest that loss of TIA-1 function may be a contributing factor promoting enhanced PGE2 levels in cancer and chronic inflammation.

5 Conclusion

The biological effects of PGE2 are diverse; however, increased PGE2 synthesis has been well established as a contributing factor in inflammation and cancer. PGE2 facilitates tumor progression through stimulation of angiogenesis, cell invasion and metastasis, and inhibition of apoptosis by signaling through its cognate EP receptors. Substantial evidence has demonstrated the role of unregulated COX-2 expression to be a primary factor promoting PGE2 synthesis in many chronic diseases and cancer, and numerous studies indicate the benefit of inhibiting COX-2 activity with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and COX-2 selective inhibitors. However, unwanted cardiovascular side effects associated with long-term COX-2 inhibition has limited their use as primary chemoprevention agents [194].

miRNAs have been linked to the progression and prognosis of cancer [59] and are promising therapeutic targets due to their unique ability to target a large number of genes [66]. Developing therapeutic strategies that will substitute or restore expression of specific miRNA families identified to control expression of genes involved in the PGE2 pathway may prove to be more comprehensive than targeting individual genes and allow for efficient restoration of normal PGE2 levels in the tumor microenvironment. Further identification and characterization of RNA-binding proteins that interact with 3′UTR AU-rich elements present in PGE2 pathway genes holds great promise for identifying novel candidates for therapeutic targeting to modify RNA-binding protein function and allow the nascent cellular posttranscriptional machinery to counteract the oncogenic effects of mRNA stabilization.

Acknowledgments

The authors were funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01CA134609) and American Cancer Society (RSG-06-122-01-CNE). We apologize to our colleagues for not being able to refer all primary work due to space limitations.

Contributor Information

Ashleigh E. Moore, Department of Biological Sciences and Center for Colon Cancer Research, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA

Lisa E. Young, Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research, RNAi Therapeutics, Cambridge, MA, USA

Dan A. Dixon, Email: ddixon@biol.sc.edu, Department of Biological Sciences and Center for Colon Cancer Research, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA.

References

- 1.Funk CD. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science. 2001;294(5548):1871–1875. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang D, Dubois RN. Eicosanoids and cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2010;10(3):181–193. doi: 10.1038/nrc2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Legler DF, Bruckner M, Uetz-von Allmen E, Krause P. Prostaglandin E2 at new glance: novel insights in functional diversity offer therapeutic chances. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biolgy. 2010;42(2):198–201. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rigas B, Goldman IS, Levine L. Altered eicosanoid levels in human colon cancer. The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 1993;122(5):518–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLemore TL, Hubbard WC, Litterst CL, Liu MC, Miller S, McMahon NA, et al. Profiles of prostaglandin biosynthesis in normal lung and tumor tissue from lung cancer patients. Cancer Research. 1988;48(11):3140–3147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hambek M, Baghi M, Wagenblast J, Schmitt J, Baumann H, Knecht R. Inverse correlation between serum PGE2 and T classification in head and neck cancer. Head & Neck. 2007;29(3):244–248. doi: 10.1002/hed.20503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheadle C, Fan J, Cho-Chung YS, Werner T, Ray J, Do L, et al. Control of gene expression during T cell activation: alternate regulation of mRNA transcription and mRNA stability. BioMed Central Genomics. 2005;6(1):75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garneau NL, Wilusz J, Wilusz CJ. The highways and byways of mRNA decay. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2007;8(2):113–126. doi: 10.1038/nrm2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fabian MR, Sonenberg N, Filipowicz W. Regulation of mRNA translation and stability by microRNAs. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2010;79:351–379. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060308-103103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Research. 2009;19(1):92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Roretz C, Gallouzi IE. Decoding ARE-mediated decay: is microRNA part of the equation? The Journal of Cell Biology. 2008;181(2):189–194. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park JY, Pillinger MH, Abramson SB. Prostaglandin E2 synthesis and secretion: the role of PGE2 synthases. Clinical Immunology. 2006;119(3):229–240. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simmons DL, Botting RM, Hla T. Cyclooxygenase isozymes: the biology of prostaglandin synthesis and inhibition. Pharmacology Reviews. 2004;56(3):387–437. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rebecchi MJ, Pentyala SN. Structure, function, and control of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Physiological Reviews. 2000;80(4):1291–1335. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang X, Edwards EM, Holmes BB, Falck JR, Campbell WB. Role of phospholipase C and diacylglyceride lipase pathway in arachidonic acid release and acetylcholine-induced vascular relaxation in rabbit aorta. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2006;290(1):H37–H45. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00491.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith WL, DeWitt DL, Garavito RM. Cyclooxygenases: structural, cellular, and molecular biology. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2000;69:145–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang D, Wang H, Shi Q, Katkuri S, Walhi W, Desvergne B, et al. Prostaglandin E(2) promotes colorectal adenoma growth via transactivation of the nuclear peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(3):285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hara S, Kamei D, Sasaki Y, Tanemoto A, Nakatani Y, Murakami M. Prostaglandin E synthases: understanding their pathophysiological roles through mouse genetic models. Biochimie. 2010;92(6):651–659. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jakobsson PJ, Thoren S, Morgenstern R, Samuelsson B. Identification of human prostaglandin E synthase: a microsomal, glutathione-dependent, inducible enzyme, constituting a potential novel drug target. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1999;96(13):7220–7225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samuelsson B, Morgenstern R, Jakobsson PJ. Membrane prostaglandin E synthase-1: a novel therapeutic target. Pharmacological Reviews. 2007;59(3):207–224. doi: 10.1124/pr.59.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watanabe K, Kurihara K, Suzuki T. Purification and characterization of membrane-bound prostaglandin E synthase from bovine heart. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1999;1439(3):406–414. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanioka T, Nakatani Y, Semmyo N, Murakami M, Kudo I. Molecular identification of cytosolic prostaglandin E2 synthase that is functionally coupled with cyclooxygenase-1 in immediate prostaglandin E2 biosynthesis. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(42):32775–32782. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003504200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tai HH, Ensor CM, Tong M, Zhou H, Yan F. Prostaglandin catabolizing enzymes. Prostaglandins & Other Lipid Mediators. 2002;68–69:483–493. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coggins KG, Latour A, Nguyen MS, Audoly L, Coffman TM, Koller BH. Metabolism of PGE2 by prostaglandin dehydrogenase is essential for remodeling the ductus arteriosus. Nature Medicine. 2002;8(2):91–92. doi: 10.1038/nm0202-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan M, Rerko RM, Platzer P, Dawson D, Willis J, Tong M, et al. 15-Hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase, a COX-2 oncogene antagonist, is a TGF-Beta-induced suppressor of human gastrointestinal cancers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2004;101(50):17468–17473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406142101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myung SJ, Rerko RM, Yan M, Platzer P, Guda K, Dotson A, et al. 15-Hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase is an in vivo suppressor of colon tumorigenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2006;103(32):12098–12102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603235103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ding Y, Tong M, Liu S, Moscow JA, Tai HH. Nad+−linked 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (15-PGDH) behaves as a tumor suppressor in lung cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26(1):65–72. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang G, Eisenberg R, Yan M, Monti S, Lawrence E, Fu P, et al. 15-Hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase is a target of hepatocyte nuclear factor 3beta and a tumor suppressor in lung cancer. Cancer Research. 2008;68(13):5040–5048. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Backlund MG, Mann JR, Holla VR, Buchanan FG, Tai HH, Musiek ES, et al. 15-Hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase is down-regulated in colorectal cancer. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(5):3217–3223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411221200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolf I, O’Kelly J, Rubinek T, Tong M, Nguyen A, Lin BT, et al. 15-Hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase is a tumor suppressor of human breast cancer. Cancer Research. 2006;66(15):7818–7823. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hughes D, Otani T, Yang P, Newman RA, Yantiss RK, Altorki NK, et al. NAD+-dependent 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase regulates levels of bioactive lipids in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Prevention Research. 2008;1(4):241–249. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thiel A, Ganesan A, Mrena J, Junnila S, Nykanen A, Hemmes A, et al. 15-Hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase is down-regulated in gastric cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2009;15(14):4572–4580. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Backlund MG, Mann JR, Holla VR, Shi Q, Daikoku T, Dey SK, et al. Repression of 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase involves histone deacetylase 2 and snail in colorectal cancer. Cancer Research. 2008;68(22):9331–9337. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tong M, Ding Y, Tai HH. Histone deacetylase inhibitors and transforming growth factor-beta induce 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase expression in human lung adenocarcinoma cells. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2006;72(6):701–709. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hull MA, Ko SC, Hawcroft G. Prostaglandin EP receptors: targets for treatment and prevention of colorectal cancer. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2004;3(8):1031–1039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhattacharya M, Peri KG, Almazan G, Ribeiro-da-Silva A, Shichi H, Durocher Y, et al. Nuclear localization of prostaglandin E2 receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1998;95(26):15792–15797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Breyer MD, Breyer RM. Prostaglandin E receptors and the kidney. American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology. 2000;279(1):F12–F23. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.1.F12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Breyer RM, Bagdassarian CK, Myers SA, Breyer MD. Prostanoid receptors: subtypes and signaling. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2001;41:661–690. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sugimoto Y, Narumiya S. Prostaglandin E receptors. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(16):11613–11617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katoh H, Watabe A, Sugimoto Y, Ichikawa A, Negishi M. Characterization of the signal transduction of prostaglandin E receptor EP1 subtype in cDNA-transfected chinese hamster ovary cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1995;1244(1):41–48. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(94)00182-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fukuda R, Kelly B, Semenza GL. Vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression in colon cancer cells exposed to prostaglandin E2 is mediated by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Cancer Research. 2003;63(9):2330–2334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fujino H, West KA, Regan JW. Phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 and stimulation of T-cell factor signaling following activation of EP2 and EP4 prostanoid receptors by prostaglandin E2. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(4):2614–2619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109440200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Namba T, Sugimoto Y, Negishi M, Irie A, Ushikubi F, Kakizuka A, et al. Alternative splicing of C-terminal tail of prostaglandin E receptor subtype EP3 determines G-protein specificity. Nature. 1993;365(6442):166–170. doi: 10.1038/365166a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kotani M, Tanaka I, Ogawa Y, Usui T, Tamura N, Mori K, et al. Structural organization of the human prostaglandin EP3 receptor subtype gene (PTGER3) Genomics. 1997;40(3):425–434. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.4585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kawamori T, Uchiya N, Nakatsugi S, Watanabe K, Ohuchida S, Yamamoto H, et al. Chemopreventive effects of ONO-8711, a selective prostaglandin E receptor EP(1) antagonist, on breast cancer development. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22(12):2001–2004. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.12.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang L, Huang Y, Porta R, Yanagisawa K, Gonzalez A, Segi E, et al. Host and direct antitumor effects and profound reduction in tumor metastasis with selective EP4 receptor antagonism. Cancer Research. 2006;66(19):9665–9672. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keith RL, Geraci MW, Nana-Sinkam SP, Breyer RM, Hudish TM, Meyer AM, et al. Prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype 2 (EP2) null mice are protected against murine lung tumorigenesis. Anticancer Research. 2006;26(4B):2857–2861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature. 2010;466(7308):835–840. doi: 10.1038/nature09267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Filipowicz W, Bhattacharyya SN, Sonenberg N. Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: are the answers in sight? Nature Reviews Genetics. 2008;9(2):102–114. doi: 10.1038/nrg2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brennecke J, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM. Principles of microRNA-target recognition. PLoS Biology. 2005;3(3):e85. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grimson A, Farh KK, Johnston WK, Garrett-Engele P, Lim LP, Bartel DP. MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: determinants beyond seed pairing. Molecular Cell. 2007;27(1):91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shin C, Nam JW, Farh KK, Chiang HR, Shkumatava A, Bartel DP. Expanding the microRNA targeting code: functional sites with centered pairing. Molecular Cell. 2010;38(6):789–802. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cullen BR. Transcription and processing of human microRNA precursors. Molecular Cell. 2004;16(6):861–865. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Altuvia Y, Landgraf P, Lithwick G, Elefant N, Pfeffer S, Aravin A, et al. Clustering and conservation patterns of human microRNAs. Nucleic Acids Research. 2005;33(8):2697–2706. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu J, Wang F, Yang GH, Wang FL, Ma YN, Du ZW, et al. Human microRNA clusters: genomic organization and expression profile in leukemia cell lines. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;349(1):59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Griffiths-Jones S, Saini HK, van Dongen S, Enright AJ. MiRBase: tools for microRNA genomics. Nucleic Acids Research. 2008;36:D154–D158. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm952. Database issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.He L, Hannon GJ. MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2004;5(7):522–531. doi: 10.1038/nrg1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nature Reviews. Cancer. 2006;6(11):857–866. doi: 10.1038/nrc1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Croce CM. Causes and consequences of microRNA dysregulation in cancer. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2009;10(10):704–714. doi: 10.1038/nrg2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ryan BM, Robles AI, Harris CC. Genetic variation in microRNA networks: the implications for cancer research. Nature Reviews. Cancer. 2010;10(6):389–402. doi: 10.1038/nrc2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Lamb J, Peck D, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature. 2005;435(7043):834–838. doi: 10.1038/nature03702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Calin GA, Dumitru CD, Shimizu M, Bichi R, Zupo S, Noch E, et al. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro- RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2002;99(24):15524–15529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242606799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Calin GA, Cimmino A, Fabbri M, Ferracin M, Wojcik SE, Shimizu M, et al. MiR-15a and miR-16-1 cluster functions in human leukemia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2008;105(13):5166–5171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800121105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chang TC, Yu D, Lee YS, Wentzel EA, Arking DE, West KM, et al. Widespread microRNA repression by Myc contributes to tumorigenesis. Nature Genetics. 2008;40(1):43–50. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Suzuki HI, Yamagata K, Sugimoto K, Iwamoto T, Kato S, Miyazono K. Modulation of microRNA processing by p53. Nature. 2009;460(7254):529–533. doi: 10.1038/nature08199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lewis BP, Shih IH, Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Burge CB. Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell. 2003;115(7):787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack FJ. Oncomirs—microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nature Reviews. Cancer. 2006;6(4):259–269. doi: 10.1038/nrc1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rehmsmeier M, Steffen P, Hochsmann M, Giegerich R. Fast and effective prediction of microRNA/target duplexes. RNA. 2004;10(10):1507–1517. doi: 10.1261/rna.5248604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kruger J, Rehmsmeier M. RNAhybrid: microRNA target prediction easy, fast and flexible. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34(suppl 2):W451–W454. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Betel D, Wilson M, Gabow A, Marks DS, Sander C. The microRNA.org resource targets and expression. Nucleic Acids Research. 2008;36:D149–D153. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm995. Database issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Griffiths-Jones S, Grocock RJ, van Dongen S, Bateman A, Enright AJ. MiRBase: microRNA sequences, targets and gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34:D140–D144. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj112. Database issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mongroo PS, Rustgi AK. The role of the miR-200 family in epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Biology & Therapy. 2010;10(3):219–222. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.6312548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sato Y, Kobayashi H, Suto Y, Olney HJ, Davis EM, Super HG, et al. Chromosomal instability in chromosome band 12p13: multiple breaks leading to complex rearrangements including cytogenetically undetectable subclones. Leukemia. 2001;15(8):1193–1202. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bagchi A, Mills AA. The quest for the 1p36 tumor suppressor. Cancer Research. 2008;68(8):2551–2556. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vrba L, Jensen TJ, Garbe JC, Heimark RL, Cress AE, Dickinson S, et al. Role for DNA methylation in the regulation of miR-200c and miR-141 expression in normal and cancer cells. PloS One. 2010;5(1):e8697. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gregory PA, Bert AG, Paterson EL, Barry SC, Tsykin A, Farshid G, et al. The miR-200 family and miR-205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nature Cell Biology. 2008;10(5):593–601. doi: 10.1038/ncb1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pang Y, Young CY, Yuan H. MicroRNAs and prostate cancer. Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica. 2010;42(6):363–369. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmq038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gibbons DL, Lin W, Creighton CJ, Rizvi ZH, Gregory PA, Goodall GJ, et al. Contextual extracellular cues promote tumor cell EMT and metastasis by regulating miR-200 family expression. Genes & Development. 2009;23(18):2140–2151. doi: 10.1101/gad.1820209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Saydam O, Shen Y, Wurdinger T, Senol O, Boke E, James MF, et al. Downregulated microRNA-200a in meningiomas promotes tumor growth by reducing E-cadherin and activating the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2009;29(21):5923–5940. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00332-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Korpal M, Lee ES, Hu G, Kang Y. The miR-200 family inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer cell migration by direct targeting of E-cadherin transcriptional repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(22):14910–14914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800074200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Spaderna S, Schmalhofer O, Wahlbuhl M, Dimmler A, Bauer K, Sultan A, et al. The transcriptional repressor ZEB1 promotes metastasis and loss of cell polarity in cancer. Cancer Research. 2008;68(2):537–544. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Uhlmann S, Zhang JD, Schwager A, Mannsperger H, Riazalhosseini Y, Burmester S, et al. MiR-200bc/429 cluster targets PLCgamma1 and differentially regulates proliferation and EGF-driven invasion than miR-200a/141 in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29(30):4297–4306. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Buchanan FG, Wang D, Bargiacchi F, DuBois RN. Prostaglandin E2 regulates cell migration via the intracellular activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(37):35451–35457. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302474200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Adam L, Zhong M, Choi W, Qi W, Nicoloso M, Arora A, et al. MiR-200 expression regulates epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in bladder cancer cells and reverses resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor therapy. Clinical Cancer Research. 2009;15(16):5060–5072. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xu N, Papagiannakopoulos T, Pan G, Thomson JA, Kosik KS. MicroRNA-145 regulates OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4 and represses pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2009;137(4):647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cordes KR, Sheehy NT, White MP, Berry EC, Morton SU, Muth AN, et al. MiR-145 and miR-143 regulate smooth muscle cell fate and plasticity. Nature. 2009;460(7256):705–710. doi: 10.1038/nature08195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang X, Liu S, Hu T, He Y, Sun S. Up-regulated microRNA-143 transcribed by nuclear factor kappa B enhances hepatocarcinoma metastasis by repressing fibronectin expression. Hepatology. 2009;50(2):490–499. doi: 10.1002/hep.23008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wu BL, Xu LY, Du ZP, Liao LD, Zhang HF, Huang Q, et al. MiRNA profile in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: downregulation of miR-143 and miR-145. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011;17(1):79–88. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Michael MZ, O’Connor SM, van Holst Pellekaan NG, Young GP, James RJ. Reduced accumulation of specific microRNAs in colorectal neoplasia. Molecular Cancer Research. 2003;1(12):882–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Akao Y, Nakagawa Y, Naoe T. MicroRNAs 143 and 145 are possible common onco-microRNAs in human cancers. Oncology Reports. 2006;16(4):845–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bandres E, Cubedo E, Agirre X, Malumbres R, Zarate R, Ramirez N, et al. Identification by real-time PCR of 13 mature microRNAs differentially expressed in colorectal cancer and non-tumoral tissues. Molecular Cancer. 2006;5:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Slaby O, Svoboda M, Fabian P, Smerdova T, Knoflickova D, Bednarikova M, et al. Altered expression of miR-21, miR-31, miR-143 and miR-145 is related to clinicopathologic features of colorectal cancer. Oncology. 2007;72(5–6):397–402. doi: 10.1159/000113489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wach S, Nolte E, Szczyrba J, Stohr R, Hartmann A, Orntoft T, et al. MiRNA profiles of prostate carcinoma detected by multi-platform miRNA screening. International Journal of Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/ijc.26064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhang H, Cai X, Wang Y, Tang H, Tong D, Ji F. MicroRNA-143, down-regulated in osteosarcoma, promotes apoptosis and suppresses tumorigenicity by targeting Bcl-2. Oncology Reports. 2010;24(5):1363–1369. doi: 10.3892/or_00000994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Song T, Xia W, Shao N, Zhang X, Wang C, Wu Y, et al. Differential miRNA expression profiles in bladder urothelial carcinomas. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2010;11(4):905–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Akao Y, Nakagawa Y, Kitade Y, Kinoshita T, Naoe T. Downregulation of microRNAs-143 and -145 in B-cell malignancies. Cancer Science. 2007;98(12):1914–1920. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00618.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Takagi T, Iio A, Nakagawa Y, Naoe T, Tanigawa N, Akao Y. Decreased expression of microRNA-143 and -145 in human gastric cancers. Oncology. 2009;77(1):12–21. doi: 10.1159/000218166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sachdeva M, Zhu S, Wu F, Wu H, Walia V, Kumar S, et al. P53 represses c-Myc through induction of the tumor suppressor miR-145. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2009;106(9):3207–3212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808042106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chen X, Guo X, Zhang H, Xiang Y, Chen J, Yin Y, et al. Role of miR-143 targeting KRAS in colorectal tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2009;28(10):1385–1392. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shi B, Sepp-Lorenzino L, Prisco M, Linsley P, deAngelis T, Baserga R. Micro RNA 145 targets the insulin receptor substrate-1 and inhibits the growth of colon cancer cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(45):32582–32590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702806200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Akao Y, Nakagawa Y, Iio A, Naoe T. Role of microRNA-143 in Fas-mediated apoptosis in human T-cell leukemia Jurkat cells. Leukemia Research. 2009;33(11):1530–1538. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tai MH, Chang CC, Kiupel M, Webster JD, Olson LK, Trosko JE. Oct4 expression in adult human stem cells: evidence in support of the stem cell theory of carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26(2):495–502. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wu Y, Liu S, Xin H, Jiang J, Younglai E, Sun S, et al. Up-regulation of microRNA-145 promotes differentiation by repressing OCT4 in human endometrial adenocarcinoma cells. Cancer. 2011;1(1):1–10. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Boultwood J, Pellagatti A, McKenzie AN, Wainscoat JS. Advances in the 5q- syndrome. Blood. 2010;116(26):5803–5811. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-273771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Starczynowski DT, Kuchenbauer F, Argiropoulos B, Sung S, Morin R, Muranyi A, et al. Identification of miR-145 and miR-146a as mediators of the 5q- syndrome phenotype. Nature Medicine. 2010;16(1):49–58. doi: 10.1038/nm.2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Elia L, Quintavalle M, Zhang J, Contu R, Cossu L, Latronico MV, et al. The knockout of miR-143 and -145 alters smooth muscle cell maintenance and vascular homeostasis in mice: correlates with human disease. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2009;16(12):1590–1598. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yau L, Zahradka P. PGE(2) stimulates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation via the EP2 receptor. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2003;203(1–2):77–90. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(03)00096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Varambally S, Cao Q, Mani RS, Shankar S, Wang X, Ateeq B, et al. Genomic loss of microRNA-101 leads to overexpression of histone methyltransferase EZH2 in cancer. Science. 2008;322(5908):1695–1699. doi: 10.1126/science.1165395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Strillacci A, Griffoni C, Sansone P, Paterini P, Piazzi G, Lazzarini G, et al. MiR-101 downregulation is involved in cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression in human colon cancer cells. Experimental Cell Research. 2009;315(8):1439–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhang JG, Guo JF, Liu DL, Liu Q, Wang JJ. MicroRNA-101 exerts tumor-suppressive functions in non-small cell lung cancer through directly targeting enhancer of zeste homolog 2. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2011;6(4):671–678. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318208eb35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Smits M, Nilsson J, Mir SE, van der Stoop PM, Hulleman E, Niers JM, et al. MiR-101 is down-regulated in glioblastoma resulting in EZH2-induced proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis. Oncotarget. 2010;1(8):710–720. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Su H, Yang JR, Xu T, Huang J, Xu L, Yuan Y, et al. MicroRNA-101, down-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma, promotes apoptosis and suppresses tumorigenicity. Cancer Research. 2009;69(3):1135–1142. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Friedman JM, Liang G, Liu CC, Wolff EM, Tsai YC, Ye W, et al. The putative tumor suppressor microRNA-101 modulates the cancer epigenome by repressing the polycomb group protein EZH2. Cancer Research. 2009;69(6):2623–2629. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wang HJ, Ruan HJ, He XJ, Ma YY, Jiang XT, Xia YJ, et al. MicroRNA-101 is down-regulated in gastric cancer and involved in cell migration and invasion. European Journal of Cancer. 2010;46(12):2295–2303. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]