Abstract

OBJECTIVE

This randomized, controlled noninferiority trial aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of insulin detemir (IDet) versus neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) (both with prandial insulin aspart) in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Patients were randomized and exposed to IDet or NPH up to 12 months before pregnancy or at 8–12 weeks gestation. The primary analysis aimed to demonstrate noninferiority of IDet to NPH with respect to A1C at 36 gestational weeks (GWs) (margin of 0.4%). The data were analyzed using linear regression, taking several baseline factors and covariates into account.

RESULTS

A total of 310 type 1 diabetic women were randomized and exposed to IDet (n = 152) or NPH (n = 158) up to 12 months before pregnancy (48%) or during pregnancy at 8–12 weeks (52%). The estimated A1C at 36 GWs was 6.27% for IDet and 6.33% for NPH in the full analysis set (FAS). IDet was declared noninferior to NPH (FAS, –0.06% [95% CI –0.21 to 0.08]; per protocol, –0.15% [–0.34 to 0.04]). Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) was significantly lower with IDet versus NPH at both 24 GWs (96.8 vs. 113.8 mg/dL, P = 0.012) and 36 GWs (85.7 vs. 97.4 mg/dL, P = 0.017). Major and minor hypoglycemia rates during pregnancy were similar between groups.

CONCLUSIONS

Treatment with IDet resulted in lower FPG and noninferior A1C in late pregnancy compared with NPH insulin. Rates of hypoglycemia were comparable.

There is a lack of randomized, controlled trials investigating basal insulin analogs as treatment in diabetic pregnant women (1). Small and uncontrolled studies have reported on the use of the long-acting basal insulin analogs insulin detemir (IDet) and insulin glargine, but both are currently placed in category C by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in pregnancy. Given the potential benefits of insulin analogs compared with more conventional human insulins, many women of child-bearing age are now receiving these analogs and would prefer to continue using them during pregnancy. Consequently, it is very important to study the safety and efficacy of basal insulin analogs in pregnant women with diabetes. The primary aim of this study was to compare glycemic control as measured by A1C at 36 gestational weeks (GWs) in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes treated with either IDet or neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH). This article presents data on glycemic control, maternal hypoglycemia, and maternal safety. Data on delivery and perinatal outcomes are to be reported separately.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

This open-label, randomized, parallel-group study conducted at 79 sites in 17 countries was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by respective ethics committees and health authorities according to local regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from subjects before study start.

The study design has been published in detail (1). In summary, eligible subjects were women with type 1 diabetes treated with insulin (any regimen) for at least 12 months before randomization and either planning to become pregnant (screening A1C ≤9.0%) or already pregnant with a singleton pregnancy at gestational age 8–12 weeks. At confirmation of pregnancy, all subjects were required to have an A1C ≤8.0%. Subjects with impaired hepatic or renal function or uncontrolled hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg), undergoing medical infertility treatment, or who had been previously randomized in this trial were excluded.

Trial design and interventions

Subjects were randomized 1:1 (using Interactive Voice/Web Response System) to either IDet (100 units/mL; Novo Nordisk, Bagsvaerd, Denmark) or NPH insulin (100 units/mL; Novo Nordisk) (both with prandial insulin aspart [100 units/mL; Novo Nordisk] in a basal-bolus regimen) and stratified according to pregnancy status (nonpregnant and pregnant at randomization). Subjects were administered the trial drug from randomization until termination/6 weeks postdelivery.

IDet and NPH insulin were administered subcutaneously at the same time of day and with the same frequency as the basal insulin that was taken prior to randomization, mainly once or twice daily.

Insulin aspart was administered before each meal. All basal insulin doses were titrated according to fasting or predinner capillary plasma glucose (PG) values (Supplementary Data online). All bolus insulin doses were titrated according to pre- and postprandial PG values (Supplementary Data online). All insulin doses (both bolus and basal) were adjusted according to a preprandial PG target of 72–108 mg/dL (4.0–6.0 mmol/L) and a 2-h postprandial glucose target of <126 mg/dL (<7.0 mmol/L).

Assessments and end points

Subjects pregnant at randomization (at 8–12 GWs) had the first study visit at this point and subsequent visits at 14, 24, and 36 GWs, delivery/termination, and 6 weeks postdelivery. Subjects not pregnant at randomization attended visits every 3 months until conception was confirmed and then were followed as described for those pregnant at randomization. Additional visits according to local practice and individual needs were also given. Subjects who did not conceive within 12 months from randomization or who did not reach an A1C ≤8.0% within 9 months were withdrawn from the trial.

The primary end point was A1C at 36 GWs as an indicator of glycemic control after treatment with IDet versus NPH insulin. Secondary efficacy end points included A1C during 8–12, 14, and 24 GWs, number of subjects obtaining a predefined goal of A1C ≤6.0% at both 24 and 36 GWs, fasting PG (FPG) values, and 8-point self-monitored PG (SMPG) profiles at 8–12, 14, 24, and 36 GWs. Maternal safety end points during pregnancy reported here included minor and major hypoglycemia, deterioration of retinopathy, and adverse events (AEs). Other maternal end points included insulin dose during the pregnancy period and weight gain calculated as weight at 36 GWs minus weight at 8–12 GWs.

Blood samples for FPG were taken with a home blood-sampling kit in the morning of each pregnancy study visit. The subject brought the sample to the trial site, and the central laboratory analyzed the samples.

Major hypoglycemia was defined as an episode in which the subject was unable to treat herself; minor hypoglycemia was defined as an episode in which the subject was able to treat herself and had a PG reading of <56 mg/dL (<3.1 mmol/L). Episodes were recorded by the subjects in their trial diaries. A hypoglycemic episode was considered treatment emergent if the onset of the episode was on or after the first day of treatment and no later than 1 day after the last day of treatment. In this article, we present treatment-emergent hypoglycemia during pregnancy.

Subjects had deterioration of retinopathy if fundoscopy progressed from “normal” at the first pregnancy visit to “abnormal” at follow-up, or from “abnormal, not clinically significant” to “abnormal, clinically significant” at follow-up. Fundoscopy/fundus photography was performed according to local practice, dated, and recorded in the trial report form, and was source-data verifiable.

Statistical analyses

The sample size was calculated based on the assumption that IDet was noninferior to NPH insulin by more than a prespecified A1C margin of 0.4% and an SD of 1.1%. On the basis of these assumptions, a total of 120 completing subjects in each group would be needed for 80% power at the 5% level of significance. Assuming a dropout rate of 20% and that only 50% of subjects would become pregnant (2,3), it was estimated that a total of 400 subjects should be randomized. After recruitment of 250 subjects in this trial, the ratio between women randomized pregnant and nonpregnant was close to 1:2, therefore requiring a total of 460 randomized subjects.

Two efficacy analysis sets were defined: the full analysis set (FAS) for pregnant subjects comprised all randomized subjects who were exposed to at least one dose of trial product and who were pregnant during the trial, and the per protocol (PP) analysis set for pregnant subjects comprised all subjects from the FAS with gestational age at delivery of at least 32 completed weeks and with no protocol violations that would influence the primary end point. Missing values were imputed using the last observation carried forward. No “last observation carried forward” was made using data from the prepregnancy period. A normal linear regression model was used to model the primary end point with treatment, country, and pregnancy status at randomization as factors, and A1C at randomization and the interaction of A1C at randomization by pregnancy status at randomization as covariates. Noninferiority was shown if the upper limit of the 95% CI for the treatment difference of IDet versus NPH was below the prespecified noninferiority margin of 0.4% for both the FAS and PP analysis sets. Safety outcomes were evaluated in the safety analysis set for pregnant subjects (exposed subjects who were pregnant during the trial). Treatment-emergent hypoglycemic episodes (including nocturnal episodes) during pregnancy were analyzed with negative binomial regression, where the number of episodes depends on treatment, pregnancy status at randomization, and country (for all and minor episodes only; country was not included in the analysis of major hypoglycemia due to lack of convergence), or where the log-transformed exposure time during pregnancy was seen as an offset variable. Details for the statistical analyses of other end points are listed in the Supplementary Data online.

RESULTS

Subjects were recruited between May 2007 and August 2010. In total, 470 subjects were randomized, and 313 women were pregnant during the study, of whom 310 (IDet, 152; NPH, 158) were exposed to study treatment (FAS) (Supplementary Data online). In total, 162 subjects were randomized during early pregnancy (IDet, 79; NPH, 83) and 148 subjects were randomized before pregnancy (IDet, 73; NPH, 75).

Two subjects in the NPH arm had a spontaneous abortion but remained in the trial and became pregnant again. Therefore, these two subjects have two pregnancies reported (Supplementary Data online).

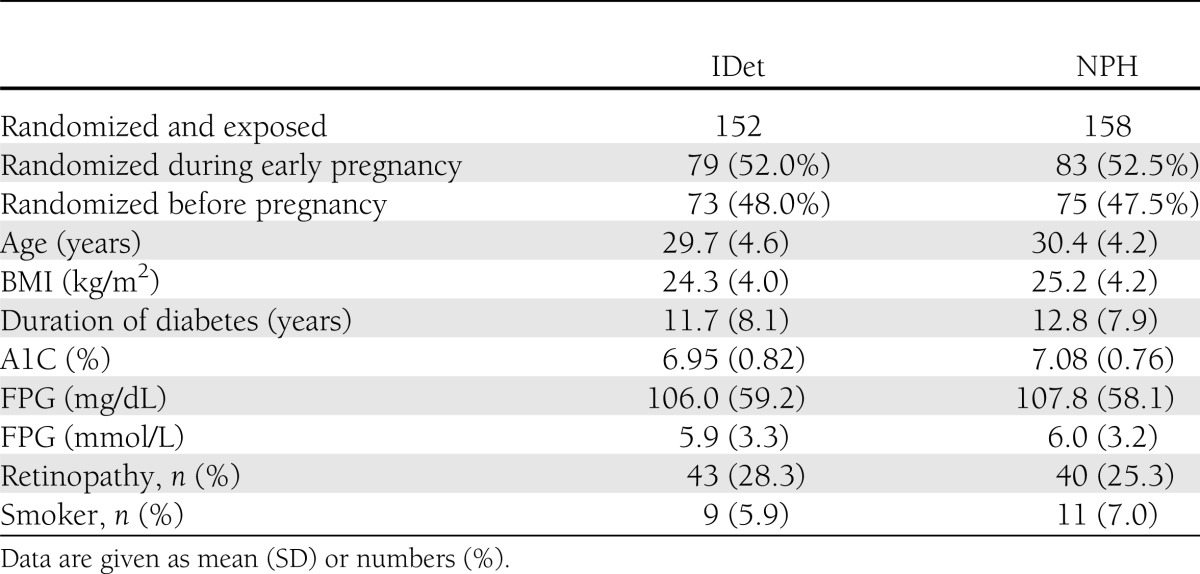

Data from the pregnant subjects are presented in this article. Patient demographics were similar between treatment groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics at baseline prior to start of study drug

Efficacy

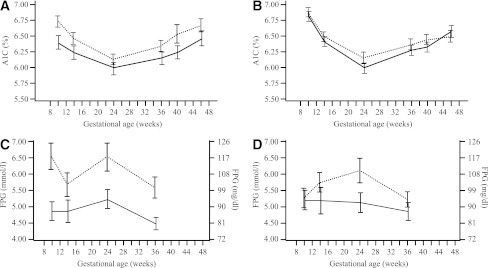

The estimated mean A1C at 36 GWs, taking several baseline factors and covariates into account, was 6.27% for IDet and 6.33% for NPH for FAS. IDet was noninferior to NPH and not superior (treatment difference in the FAS, –0.06 [95% CI –0.21 to 0.08]; PP analysis set, –0.15 [–0.34 to 0.04]). The actual A1C values during pregnancy for all subjects randomized before or during early pregnancy are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Mean A1C (%) in subjects randomized before pregnancy (A) or during early pregnancy (B). Mean FPG (mmol/L) in subjects randomized before pregnancy (C) or during early pregnancy (D). All values are mean ± SEM. Detemir, solid line; NPH, dotted line.

When the two strata of subjects “randomized before pregnancy” and “randomized during early pregnancy” were examined separately, the A1C levels at 36 GWs were again demonstrated to be comparable (IDet, 6.11%; NPH, 6.19%; treatment difference, –0.07% [–0.29 to 0.15] vs. IDet, 6.39%; NPH, 6.44%; treatment difference, –0.05% [–0.25 to 0.14]).

The treatment goal of A1C ≤6.0% at both 24 and 36 GWs was obtained in 41% of the subjects in the IDet group and 32% in the NPH group (P = 0.280), and this difference seemed more pronounced in subjects who were randomized before pregnancy (IDet, 48%; NPH, 34%) than in subjects who were randomized during early pregnancy (IDet, 36%; NPH, 29%).

Estimated mean FPG (95% CI) was significantly lower with IDet compared with NPH at both 24 (96.8 mg/dL [5.4 mmol/L] vs. 113.8 mg/dL [6.3 mmol/L] [95% CI –30.1 to –3.8/–1.7 to –0.2]; P = 0.012) and 36 GWs (85.7 mg/dL [4.8 mmol/L] vs. 97.4 mg/dL [5.4 mmol/L] [95% CI –21.4 to –2.2/–1.2 to –0.1]; P = 0.017). The overall difference between groups was more pronounced in subjects who were randomized before pregnancy (Fig. 1).

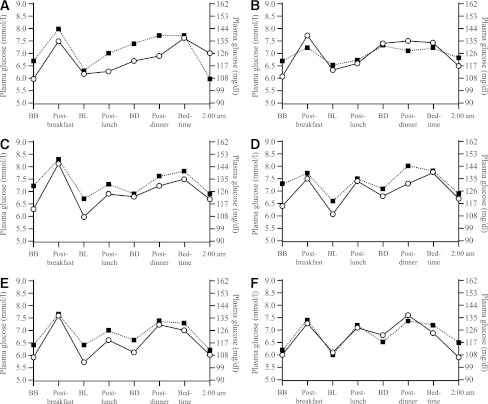

The 8-point SMPG profiles were regarded as parallel at both 24 (P = 0.139) and 36 GWs (P = 0.671). Mean PG from the 8-point SMPG profile was significantly lower with IDet than NPH at 24 GWs (125.1 mg/dL [6.95 mmol/L] vs. 132.8 mg/dL [7.38 mmol/L]; treatment difference, –7.7 mg/dL [–0.43 mmol/L] [95% CI –13.0 to –2.5/–0.72 to –0.14]; P = 0.003). PG was also lower with IDet compared with NPH at 36 GWs, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (119.0 mg/dL [6.61 mmol/L] vs. 123 mg/dL [6.85 mmol/L]; treatment difference, –4.3 mg/dL [–0.24 mmol/L] [95% CI –9.2 to 0.5/–0.51 to 0.03]; P = 0.082). Figure 2 demonstrates the 8-point profiles measured during pregnancy in the women randomized before or during early pregnancy. There appeared to be a greater separation of the two 8-point profiles that favored IDet in women randomized to treatment prior to pregnancy compared with during pregnancy, although this did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 2.

Mean PG profile at 14, 24, and 36 GWs in subjects randomized before pregnancy or randomized in early pregnancy by pregnancy status at randomization. A: Mean PG profile in subjects randomized before pregnancy in GW 14. B: Mean PG profile in subjects randomized in early pregnancy at GW 14. C: Mean PG profile in subjects randomized before pregnancy at GW 24. D: Mean PG profile in subjects randomized in early pregnancy at GW 24. E: Mean PG profile in subjects randomized before pregnancy at GW 36. F: Mean PG profile in subjects randomized in early pregnancy at GW 36. BB, before breakfast; BD, before dinner; BL, before lunch. Detemir, circle + solid line; NPH, square + dotted line.

Tolerability

Hypoglycemia.

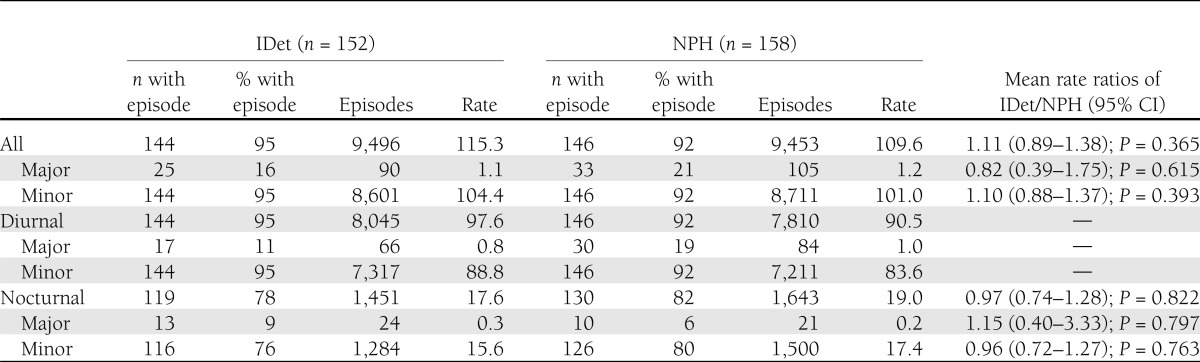

Major hypoglycemic episodes during pregnancy were similar between the two groups, occurring in 16% of the subjects in the IDet group and 21% in the NPH group. There were no statistically significant differences between the two treatments for the analyzed hypoglycemic episodes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hypoglycemia rates during pregnancy (episodes/year)

The proportion of mothers having one or more AEs during pregnancy was the same in both treatment groups (∼90%), and the rate of AEs was similar in both groups, being a little less than 800 events per 100 exposure-years. No maternal deaths were reported. Serious AEs (SAEs) occurred in numerically more mothers during pregnancy in the IDet group than in the NPH group (40 vs. 31%) (further details are included in the Supplementary Data online). Few events were considered by the investigator to be possibly or probably related to one or both investigational products (between 8 and 12% of the mothers), and there was no difference between the treatment groups in incidence. During pregnancy, the main differences in SAEs between the insulins were in pregnancy, puerperium, and perinatal conditions (to be reported in a separate article) and metabolism and nutrition disorders; 11% of the mothers in the IDet group and 8% in the NPH group had SAEs within the category of “metabolism and nutrition disorders,” including hypoglycemic unconsciousness (two patients in the IDet group and seven in the NPH group), diabetes inadequate control (five patients in the IDet group and one in the NPH group), and three cases of diabetic ketoacidosis (in the IDet group).

Eight women in the IDet group reported eight AEs relating to injection-site reactions, but only one withdrew from the study. A similar proportion of subjects in the two treatment groups (12 subjects [7.9%] in the IDet group and 14 [8.9%] in the NPH group) had deterioration of retinopathy during pregnancy. Further maternal obstetric outcome details, such as preeclampsia, are to be reported in a separate article.

Insulin dose and weight gain.

Mean total doses of basal and bolus insulin increased during pregnancy from 0.73 and 0.74 units/kg in the IDet and NPH groups, respectively, at 14 GWs, to 1.17 and 1.05 units/kg at 36 GWs, and decreased during follow-up to 0.53 and 0.57 units/kg, respectively. The increase during pregnancy was most pronounced for bolus insulin (Supplementary Fig. 1). Mean doses of basal insulin were similar in the two treatment groups (Supplementary Fig. 2). There was no difference between groups in weight gain during pregnancy (11.5 kg in the IDet group and 11.0 kg in the NPH group).

CONCLUSIONS

This study is the first randomized, controlled clinical trial, to date, of a basal insulin analog in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes. IDet was noninferior to NPH with regard to A1C at 36 GWs. A total of 41% of the subjects in the IDet group and 32% of the subjects in the NPH group reached the ambitious target of A1C ≤6.0% both at 24 and 36 GWs. Of note is the fact that FPG was significantly lower with IDet compared with NPH insulin at 24 and 36 GWs, but, reassuringly, this was not at the expense of an increase in hypoglycemia. A similar reduction in FPG has also been reported with IDet compared with NPH insulin in trials involving nonpregnant patients with type 1 diabetes (4,5).

It is well recognized that hypoglycemia and, in particular, nocturnal events occur more frequently during pregnancy, especially given the intensive insulin treatment required to reach very strict glycemic control (6–9). Up to 45% of pregnant women with type 1 diabetes mainly treated with NPH insulin are reported to have had severe hypoglycemia (9). In nonpregnant subjects with type 1 diabetes, IDet is associated with lower occurrence of nocturnal hypoglycemia compared with NPH insulin (4,5). Although the rate of major nocturnal hypoglycemia in our study was not lower with IDet compared with NPH insulin, it is reassuring that only a minority of patients experienced such an event in either group (IDet, 9%; NPH, 6%). In addition, the rates of major hypoglycemia were ∼40% lower in this study compared with women treated with human insulin in the insulin aspart study (2); it is reasonable to speculate that this is partly due to the women in the current study having more experience in using the analogs.

There were a greater number of maternal SAEs in the IDet-treated group compared with the NPH-treated group during the pregnancy period. For pregnancy, puerperium, and perinatal conditions and metabolism and nutrition disorders, in some cases underlying confounders could be identified and only a few cases were judged attributable to the insulin used, therefore not resulting in any concerns regarding the tolerability of either insulin.

The open-label nature of the trial does mean that it could have been influenced by possible confounding factors; however, it would have been unfeasible to conduct it in any other way given the nature of the insulins.

The development of insulin analogs has provided a greater choice for patients with diabetes than in the past, and it appears that their use in pregnancy is increasing. At the time of initiation of the insulin aspart trial in 2002 in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes, pretrial analog use was reported at ∼48% (2); in the current trial, bolus analog use at baseline was reported at ∼90% (1) and basal analog use at ∼47% (1). This may reflect a change in the perception of the safety of insulin analog use in pregnancy, supported by FDA endorsement.

In summary, treatment with IDet was noninferior to NPH, as demonstrated by A1C measurements at 36 GWs. A significantly lower FPG concentration at 24 and 36 GWs occurred with IDet compared with NPH insulin, which, in the absence of increased rates of hypoglycemia, would suggest additional clinical usefulness. These data suggest that IDet is at least as effective as NPH when used as a basal insulin in a basal-bolus regimen with insulin aspart in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes, and that IDet has the potential to offer some clinical benefits in terms of FPG control.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Novo Nordisk. E.R.M. is a member of an international scientific advisory board and has received fees for giving talks for Novo Nordisk. L.B. is an employee of Novo Nordisk and owns stocks in the company. M.H., L.J., and P.D. are members of an international scientific advisory board for Novo Nordisk. D.R.M. is a member of an international scientific advisory board, contributed to advisory committees, and has received honoraria from Novo Nordisk in the past for giving lectures. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

E.R.M. researched data, contributed to discussion, and wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. M.H., M.I., S.D.G., L.B., L.J., P.D., and D.R.M. researched data, contributed to discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. E.R.M. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Parts of this study were presented at the 6th International Symposium on Diabetes and Pregnancy, Salzburg, Austria, 23–26 March 2011; the 71st Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, San Diego, California, 24–28 June 2011; the 47th European Association for the Study of Diabetes Annual Meeting, Lisbon, Portugal, 12–16 September 2011; and the World Diabetes Congress, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 4–8 December 2011.

The authors thank Liz Southey and Daria Renshaw (Watermeadow Medical, Witney, U.K.) for their help with preparing the manuscript.

Footnotes

See accompanying commentary, p. 1968.

This article contains Supplementary Data online at http://care.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/dc11-2264/-/DC1.

Clinical trial reg. no. NCT00474045, clinicaltrials.gov.

References

- 1.Mathiesen ER, Damm P, Jovanovič L, et al. Basal insulin analogues in diabetic pregnancy: a literature review and baseline results of a randomised, controlled trial in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2011;27:543–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathiesen ER, Kinsley B, Amiel SA, et al. Insulin Aspart Pregnancy Study Group Maternal glycemic control and hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetic pregnancy: a randomized trial of insulin aspart versus human insulin in 322 pregnant women. Diabetes Care 2007;30:771–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hod M, Damm P, Kaaja R, Visser GH, Dunne F, Demidova I, et al. Insulin Aspart Pregnancy Study Group. Fetal and perinatal outcomes in type 1 diabetes pregnancy: a randomized study comparing insulin aspart with human insulin in 322 subjects. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;198:186.e1–e7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Hermansen K, Fontaine P, Kukolja KK, Peterkova V, Leth G, Gall MA. Insulin analogues (insulin detemir and insulin aspart) versus traditional human insulins (NPH insulin and regular human insulin) in basal-bolus therapy for patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2004;47:622–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartley PC, Bogoev M, Larsen J, Philotheou A. Long-term efficacy and safety of insulin detemir compared to neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin in patients with type 1 diabetes using a treat-to-target basal-bolus regimen with insulin aspart at meals: a 2-year, randomized, controlled trial. Diabet Med 2008;25:442–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenn BM, Miodovnik M, Holcberg G, Khoury JC, Siddiqi TA. Hypoglycemia: the price of intensive insulin therapy for pregnant women with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol 1995;85:417–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evers IM, ter Braak EWMT, de Valk HW, van Der Schoot B, Janssen N, Visser GH. Risk indicators predictive for severe hypoglycemia during the first trimester of type 1 diabetic pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2002;25:554–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ter Braak EW, Evers IM, Willem Erkelens D, Visser GH. Maternal hypoglycemia during pregnancy in type 1 diabetes: maternal and fetal consequences. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2002;18:96–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nielsen LR, Pedersen-Bjergaard U, Thorsteinsson B, Johansen M, Damm P, Mathiesen ER. Hypoglycemia in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes: predictors and role of metabolic control. Diabetes Care 2008;31:9–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.