Abstract

Human SULT2A1 is one of two predominant sulfotransferases in liver and catalyzes transfer of the sulfuryl-moiety (-SO3) from activated sulfate (PAPS, 3′-phosphoadenosine 5-phosphosulfate) to hundreds of acceptors - metabolites and xenobiotics. Sulfation recodes the biologic activity of acceptors by altering their receptor interactions. The molecular basis on which these enzymes select and sulfonate specific acceptors from complex mixtures of competitors in-vivo is a long standing issue in the SULT field. Raloxifene, a synthetic steroid used in the prevention of osteoporosis, and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), a ubiquitous steroid precusor, are reported to be sulfated efficiently by SULT2A1 in-vitro; yet, unlike DHEA, raloxifene is not sulfated in-vivo. This selectivity was explored in initial-rate and equilibrium-binding studies that demonstrate pronounced binding-antisynergy (21-fold) between PAPS and raloxifene, but not DHEA. Analysis of crystal structures suggests that PAP binding restricts access to the acceptor-binding pocket by restructuring a nine-residue segment of the pocket edge that constricts the active-site opening, or “pore” that sieves substrates based on their geometries. In-silico docking predicts that raloxifene, which is considerably larger than DHEA, can bind only to the unliganded (open) enzyme, whereas DHEA binds both the open and closed forms. The predictions of these structures regarding substrate binding are tested using equilibrium and presteady state ligand-binding studies, and the results confirm that a nucleotide-driven isomerization controls access to the acceptor binding pocket and plays an important role in substrate selection by SULT2A1 and possibly other sulfotransferases.

Keywords: sulfotransferase, SULT, SULT2A1, DHEA, raloxifene, Evista, kinetic, mechanism, ligand, binding, presteady, fluorescence, structure, selection, substrate

Sulfation of a biomolecule is often essential to controlling its biologic activity. Hundreds of molecules and their attendant metabolic processes are regulated via sulfation – steroid- (1–3), peptide- (4), dopamine- (5) and thyroid- (6) receptors, the immune system (7), lymph circulation (8), hemostasis (9), pheromone reception (10), growth factor recognition (11) and more…. Normal functioning of these processes often depends on the presence or absence of a single, critically positioned sulfuryl-group. Among the human diseases linked to improper sulfation are cancer of the breast (12) and endometrium (13), Parkinson’s disease (14), cystic fibrosis (15), hemophilia (16) and heart disease (1, 17).

Transfer of the sulfuryl-moiety (-SO3) from activated sulfate (3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate, PAPS) to biological recipients is catalyzed by sulfotransferases (18). Human cytosolic sulfotransferases are a small, 13-member group of conserved, soluble enzymes (19). Four such sulfotransferases are detected in adult human liver (20–21). In addition to their homeostatic functions (2, 22), these four enzymes sulfonate a myriad compounds as they pass into the liver from the digestive tract (18, 23). Two of the enzymes, SULT1A1 and SULT2A1 comprise 80 – 90 percent of liver sulfotransferases by mass, and are responsible for the majority of the sulfation that occurs there (21). The specificities of these enzymes are necessarily broad, and together they define the structures that are selected for sulfation from the liver milieu (20–21). The molecular basis of this selection has not been defined, and is the topic of this manuscript.

SULT2A1 is known to sulfonate steroids, drugs and other xenobiotics, and is highly selective for DHEA (dehydroepiandrosterone) (18, 24). DHEA, the most abundant circulating steroid in humans, is a pro-hormone that circulates in the sulfated form and can be converted, as needed, to any of a number of steroids in situ (25). The sulfation of drugs is common and often prevents them from binding their receptors (26). Raloxifene (Evista®), one of many drugs sulfated by SULT2A1, is taken daily by approximately 1.2 million women in the United States to prevent osteoporosis and decrease the risk of breast cancer (27–28). The structures of raloxifene and DHEA differ markedly (Fig 1), yet both are believed to be efficiently sulfated by SULT2A1 (29–30). Raloxifene is composed of a planar steroid-like “base” structure whose dimensions are roughly similar those of DHEA and a large R-group (the key to its receptor antagonism (31)) with dimensions also comparable DHEA. Notably, DHEA is sulfated (> 99%) in-vivo (32), and raloxifene is not (33).

Figure 1.

The structures of DHEA and raloxifene.

In an attempt to reconcile the in-vivo and in-vitro findings, raloxifene and DHEA were used as probes to explore the selectivity of SULT2A1. The study revealed that a previously undescribed 21-fold antisynergy between PAPS and raloxifene (but not DHEA) is the likely source of the discrepancy. Structures suggested the antisynergy might be due to a nucleotide-gated isomerization that causes an edge of the acceptor-binding pocket to “swing” into a position that sterically prevents access of raloxifene while admitting DHEA (34–36). The model-specific predictions of the isomerization mechanism were tested in equilibrium and presteady state ligand-binding studies, and the results provide strong support for the mechanism. It appears that among the mechanisms used by sulfotransferases to select substrates is a PAPS-gated steric screen - a molecular sieve that rejects or accepts substrates on the basis of their dimensions.

Materials and Methods

The materials and sources for the work are as follows: dithiothreitol (DTT), EDTA, L-glutathione (reduced), glucose, imidazole, isopropyl-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside (ITPG), LB media, lysozyme, β-mercaptoethanol, pepstatin A, raloxifene, DHEA, and potassium phosphate were the highest grade available from Sigma. Ampicillin, HEPES, KOH, MgCl2, NaCl, KCl, and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride were purchased from Fisher Scientific. [3H]-DHEA (90 Ci/mmol) was purchased from NEN Life Science Products, [3H]-RAL (34.4 Ci/mmol) was purchased from Moravek Biochemical. Glutathione- and nickel-chelating resins were obtained from GE Healthcare. Competent E. coli (BL21(DE3)) was purchased from Novagen. Simulations were performed on a Parallel Quantum Solution QS32-2670C-XS8 computer. MODELLER was provided by the University of California, San Francisco, and GOLD was obtained from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center.

Protein Purification

SULT2A1 DNA was inserted into a triple-tag pGEX-6P expression vector with an N-terminal His/GST/MBP tag (22, 37). The plasmid was transfected into BL-21(DE3) E. coli and was grown at 37 °C in LB medium containing ampicillin (100 g/ml) to an A600 of 0.7. Expression was induced with ITPG (0.7 mM). The temperature was reduced to 18 °C eight hours following induction, and cells were harvested 16 h later. SULT2A1 was purified according to a published protocol (38). Briefly, the cell pellet was suspended in KPO4 (50 mM, pH = 7.3, 25 °C) containing lysozyme (0.10 mg/mL), PMSF (290 μM), pepstatin A (1.5 μM), KCl (0.40 M), β-mercaptoethanol (5.0 mM). The mixture was stirred for 1 h at 4 °C prior to sonication (Branson Sonifier). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (60 min, 4 °C, RCF = 34 000 × g) and the supernatant was loaded onto a 5 mL Chelating Sepharose Fast Flow column charged with Ni2+. The fusion protein was eluted from the Ni2+ column with imidazole (250 mM) directly onto a glutathione sepharose column. The glutathione sepharose column was then washed, and the fusion protein was eluted with GSH (10 mM). The fusion protein was then digested with Precision Protease in an overnight dialysis against HEPES/K+ (50 mM, pH = 7.5), DTT (1.5 mM), and KCl (50 mM) at 4 °C. After dialysis, the sample was passed back through the glutathione column to remove the His/GST/MBP tag and Precision Protease. The flow-through containing SULT2A1 was collected and concentrated in an Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter (10 kDa cutoff) and stored at −80 °C in 40% glycerol. The protein preparations were assessed using SDS–PAGE and were > 97% pure. Protein concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically (ε280 = 35.7 mM−1 cm−1)(2).

Initial-Rate Kinetics

Experimental design and solution compositions are describe in the Fig 2 legend. Reactions were quenched by rapid hand-mixing of 10 μL of reaction with 1.0 μL of 0.50 M KOH. Sulfated and non-sulfated acceptors were separated by extracting the non-sulfated species into choloroform using the following protocol: 190 μL of KPO4 (25 mM, pH 8.8) was added to the quenched solution to neutralize base and increase volume. 1.0 mL of chloroform was added and the mixture was vortexed vigorously for 15 sec and centrifuged. The aqueous phase was removed and again extracted with 1.0 mL of chloroform. Sulfated acceptor in the aqueous phase was quantified using a Perkin Elmer W450624 scintillation spectrometer.

Figure 2. An initial-rate study of raloxifene and DHEA sulfation.

Rates were determined at each of the 16 conditions defined by a 4 × 4 matrix of substrate concentrations that varied from 0.2 – 5.0 × Km in equal increments in double-reciprocal space. Reactions were initiated by the addition of PAPS to solution containing [3H]-acceptor. Rates were obtained from slopes of 4-point progress curves in which less than 5% of concentration-limiting reactant consumed at the reaction endpoint was converted to product. Conditions were as follows: SULT2A1 (0.20 μM), MgCl2 (5.0 mM), KPO4 (25 mM, pH 7.4), 25 ± 2 °C. Raloxifene and DHEA concentrations are indicated in the figures. PAPS concentrations were as follows: (A) 30, 3.3, 1.8 and 1.2 μM; (B) 2.5, 0.28, 0.15 and 0.1 μM. Each point represents the average of two independent determinations. The lines through the points represent behavior predicted by a weighted least-squares fit to a sequential Bi-Bi model (48). Quenching, separation and quantitation protocols are described in Materials and Methods.

Ligand Binding Studies

Binary Complexes

Binding of nucleotide and acceptor to SULT2A1was monitored via changes in the intrinsic fluorescence of the enzyme at λex = 290 nm, λem = 340 nm. Titrants were added to a solution containing SULT2A1 (0.05 μM), MgCl2 (5.0 mM), KPO4 (25 mM), pH 7.4, 25 ± 2 °C. Dilutions due to titrant addition were negligible (< 1.8 % at titration endpoints). Nucleotide was added from an aqueous buffered stock. Acceptor was added from a stock containing 50% ethanol. Controls ensured that the ethanol did not detectably contribute to fluorescence or modify the acceptor affinity. Titrations were performed in triplicate. The data were averaged and fit by least-squares fit to a model that assumes a single binding site per monomer.

Ternary Complex

Ternary complex interactions can cause Kd and fluorescent intensity to vary as the fixed-variable ligand concentration is varied at subsaturating concentrations. To obtain Kd and intensity amplitudes at saturation of both ligands, titrations were performed using a matrix of ligand concentrations and the results fit simultaneously using a global model. The concentration matrix consisted of 5 PAP and 12 donor concentrations. PAP ranged from zero to 5 × Kd for the ternary complex; raloxifene and DHEA concentrations varied in equal increments from zero to 50 and 20 μM, respectively. Absolute PAP concentrations were: 0, 5.0, 25, 50, and 125 μM PAP, and 0, 1.0, 5.0, 10, and 25 μM PAP for the raloxifene and DHEA titrations. Conditions and protocols are described in the previous paragraph.

The algebraic model used to fit the titration data

The fluorescent intensity at a given ligand concentration (Ii) relative to that at zero ligand is given by equation 1:

| (1) |

where Ex and Ix represent the concentration and concentration-normalized fluorescent intensity of each enzyme species. ET is the total enzyme concentration. By substituting equation 2 into equation1 and

| (2) |

using dissociation constants to express each species in terms of unliganded enzyme, I/Io can be cast solely in terms of dissociation constants, ligand concentrations and intensities. The result, equation 3, was used to fit the titrations.

| (3) |

where,

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

Ii/Io and the parameters that comprise c1 – c4 are known at each point in the ligand-concentration matrix.

In-silico docking of DHEA and RAL

A ligand-free model of SULT2A1 was constructed from the SULT2A1·DHEA (1J99) (34) binary structure, and a model of SULT2A1·PAPS was developed from the SULT2A1·PAP (1EFH) (35) binary structure. Each model was prepared using homology modeling with MODELER (39) to determine the position of missing atoms. A sulfuryl-group was added to PAP to form PAPS in the SULT2A1·PAPS model. The models were then protonated and energy minimized using GOLD (40). DHEA and RAL were docked into the models using a Lamarckian, evolution-based algorithm (GOLD). The lowest energy orientation obtained after 2500 generations was analyzed and considered competent if the predicted free energy of binding was favorable and the ligand hydroxyl was properly oriented to accomplish catalysis and hydrogen bonded to H99, a universally conserved general base. Each simulation was repeated 10 times, and the lowest-energy structures were used in Figure 4.

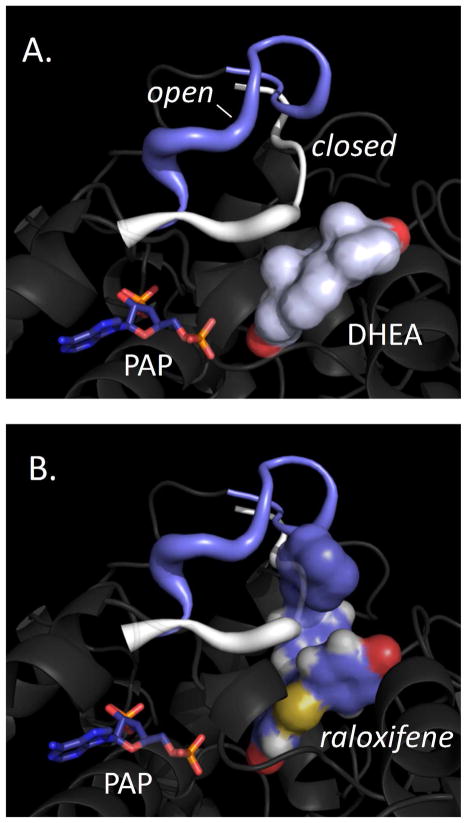

Figure 4. Nucleotide-linked gate closure discriminates substrates.

(A) DHEA positions well for chemistry in the open and closed complexes. (B) Raloxifene is sterically prevented from accessing the acceptor binding pocked in the closed, but not the open complex. Open and closed models were constructed from the SULT2A1·DHEA (1J99) and SULT2A1·PAP (1EFH) binary structures, and ligands were docked using an evolution-based algorithm (Materials and Methods).

Presteady state binding

Presteady state fluorescence experiments were performed using an Applied Photophysics SX20 stopped-flow spectrometer. Samples were excited at 285 nm, and light emitted above 320 nm was detected using a cutoff filter. The sequential mixing experiments were carried out with an SQ.1 sequential-mixing accessory. A solution containing SULT2A1 (0.10 μM), MgCl2 (5.0 mM) and KPO4 (25 mM, pH 7.4), 25 ± 2 °C was rapidly mixed (1:1) with a solution lacking SULT2A1 but containing RAL, DHEA or PAPS. Binding was monitored by following changes in the intrinsic fluorescence of the enzyme. Typically, 8 progress curves were accumulated at a given ligand concentration and averaged to produce a composite curve. Three independently acquired composite curves were averaged to generate the data-set used to obtain apparent rate constants. Data were fit using Applied Photophysics Pro-Data analysis software (Marquardt fitting algorithm).

Fifteen percent of SULT2A1 denatures during the push phase of the stopped-flow experiment. Denaturation occurs before mixing in the optical cell and results in a slow decrease in fluorescence intensity caused by the settling of the precipitate. The rate and magnitude of the precipitation was remarkably consistent. The precipitation amplitude is small and the settling rate is quite slow relative to ligand-binding reactions (kprecipitate = 0.030 sec−1). All binding data were corrected for precipitation during analysis.

Results and Discussion

Raloxifene and PAPS bind antisynergistically

An initial-rate study was performed to define differences in the interactions of raloxifene and DHEA with SULT2A1. The results indicate that raloxifene and DHEA behave similarly toward the unliganded enzyme, but differ markedly in their interactions with E·PAPS (Table 1). The best-fit lines passing through the double-reciprocal plots of the data intersect below the horizontal axis when the acceptor is raloxifene, and on (or near) the axis when it is DHEA (Fig 2A and B). The vertical component of this intersection is given by kcat · (1- Km/Ki), where Ki and Km represent the affinity of substrate A at concentrations of B extrapolated to zero and infinity, respectively. As such, the ratio of these constants reports the effect of B on the affinity of A, and is a measure of substrate synergy. The kinetic constants reveal a 21-fold antisynergy in the interaction of PAPS and raloxifene and slight positive synergy (1.4-fold) in the interactions with DHEA (Table 1). To our knowledge, this is the first report of substrate antisynergism in the sulfotransferase field.

Table 1.

Initial Rate Kinetic Constants

| Substrate | Km (μM) | Kia (μM) | Kia/Km | kcat (sec−1) | kcat/Km |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DHEA | 1.3 (0.1)1 | 1.8 (0.1) | 1.4 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.03) | 0.54 (0.07) |

| PAPS

|

0.39 (0.01) | 0.47 (0.06) | |||

| RAL | 24.8 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.1) | 23 (1.0) | 0.10 (0.01) | 0.004 (0.0003) |

| PAPS | 5.9 (0.6) | 0.24 (0.04) |

Parentheses enclose standard error estimates.

Raxofiene is a poor substrate

Previous work suggests that Km for raloxifene is 3.5 μM (29). This value was determined at a single concentration of PAPS (10 μM) that far exceeds typical PAPS Km values (~ 0.3 μM (30)), and was thought to be saturating. The current work, which varies PAPS concentration, reveals that the raloxifene Km (25 μM) is considerably larger than originally thought. This difference is due to the subsaturating concentration of PAPS used in the earlier study (1.7 × Km). The kinetic constants in Table 1 predict an apparent Km for raloxifene at 10 μM PAPS of 5.1 μM - which agrees reasonably with the earlier work. kcat/Km, the second-order rate constant for conversion of substrate to product, is often taken as a measure of the selectivity of an enzyme toward a particular substrate. kcat/Km for DHEA is 135-fold greater than that for raloxifene; thus, at identical concentrations of DHEA and raloxifene (where [S] ≪ Km for both substrates), DHEA will be sulfated 135-fold faster than raloxifene. Relative to DHEA, raloxifene is a poor substrate and it is perhaps not surprising that it is not sulfated well in-vivo (33).

Ligand binding at equilibrium

The initial-rate studies reveal antisynergistic interactions between raloxifene and PAPS, but not DHEA. If the binding reactions are at, or near equilibrium during turnover, the interaction differences are due to changes either in the ligand-binding equilibrium constants, or equilibria linked to the binding reaction. If binding is not at equilibrium, due to turnover, the differences are due to the changes in the steady-state “set-points” of the binding reactions that occur when raloxifene is “swapped” for DHEA. Shifting away from equilibrium typically causes steady-state affinity constants to be larger than their analogous equilibrium values. Equilibrium effects are caused by the shifting of Gibbs potentials of stable enzyme forms relative to one another; whereas, steady-state effects are due to changes in relative magnitudes of rate constants that govern separate steps in the mechanism. Thus, distinguishing equilibrium from steady-state mechanisms is tantamount to determining whether antisynergy is due to changes in ground- or transition-state energetics.

The equilibrium-binding interactions between nucleotide and acceptor were studied via fluorescence titrations (Fig 3). SULT2A1 undergoes substantial decreases (20 – 60 %) in intrinsic fluorescence (λex = 290, λem = 340) in response to the formation of binary or ternary complexes. PAP, rather than PAPS was used in these studies to avoid complications due to turnover. The binding constants obtained from the titrations agree well with the analogous initial-rate constants, suggesting that PAP is a reasonable surrogate for PAPS. Further support for this position is given by the results of the presteady state binding experiments described below. These experiments utilize PAPS and circumvent the turnover issue by monitoring binding on timescales short relative to turnover. The affinities obtained in the presteady state work are nearly identical to the equilibrium-binding affinities determined using PAP.

Figure 3. Equilibrium binding of RAL and DHEA to SULT2A1.

(A) Raloxifene binding to E and E·PAP. Binding is monitored by changes in intrinsic enzyme fluorescence (λex = 290, λem = 340). Solution composition is as follows: SULT2A1 (0.20 μM), PAP (0 or 125 μM), MgCl2 (5.0 mM), KPO4 (25 mM, pH 7.4), 25 ± 2 °C. Fluorescence intensity (ΔI) is normalized to total fluorescence change (ΔItotal). Each point is the average of two independent determinations. The line through the data is the behavior predicted by least-squares fitting using a model that assumes a single binding site per subunit. Further details are described in Materials and Methods. (B) DHEA binding to E and E·PAP. Conditions were identical to those described in Panel A except that PAP was 25 μM. (C) Quantitating ternary-complex binding interactions. Raloxifene solubility prevents saturation of the ternary complex. To quantitate the ternary-complex interactions, titrations with acceptor were carried out at series of five PAP concentrations, and Kd values were obtained by simultaneously fitting the data from the five titrations. Y-axis values report fold change in the acceptor affinity constant, and are given as the ratio of Kd at a fixed non-zero PAP concentration to that at zero PAP (Kd (PAP = X)/Kd (PAP = 0)). PAP concentrations were selected to range from 0 – 25 times its ternary-complex Kd; hence, X-axis values are given as [PAP] divided by its affinity constant ([PAP]/Kd (E · Acceptor)). The absolute PAP concentrations were: 0, 5.0, 25, 50, and 125 μM (raloxifene titration); and 0, 1.0, 5.0, 10, and 25 μM (DHEA titration). Further details are given in Materials and Methods.

The results of the binding studies are presented in Figure 3 and Table 2. The data are plotted as fraction change in fluorescence (ΔI/ΔItot) vs concentration. PAP and PAPS bind E with virtually identical affinity, 280 and 300 nM (Table 2); hence, addition of the moiety that is transferred during chemistry contributes little to binding affinity. The binding of raloxifene and DHEA to E and E·PAP is shown in Fig 3A and B. The PAP concentration in these titrations, 125 μM, is high enough that the enzyme remains saturated with nucleotide throughout the four titrations shown in Panels A and B. Having PAP bound clearly weakens the affinity of raloxifene, and has no discernible effect on the affinity of DHEA. The solubility of raloxifene (Ks = 55 μM (27)) is high enough to allow saturation of E (Kd = 1.1 μM) but not E·PAPS (Kd = 25 μM). The highest raloxifene concentration used in the Panel A titration (50 μM) is near the limit of its solubility. Saturation with raloxifene was not achieved in this titration; consequently, reliable binding constants and amplitudes could not be obtained. Had saturation occurred, the associated binding constant and amplitude would pertain only to a single PAPS concentration. These problems were solved by performing acceptor titrations at a series of five PAP concentrations and fitting the titrations simultaneously to extract true ternary-complex amplitudes and affinity constants (Materials and Methods). The result of the fit is presented in Fig 3C. The Y-axis is given in terms of fold-antisynergy; that is, Kd at a given PAP concentration to that at zero PAP. The PAP concentrations in these titrations ranged from 0 – 25 x the ternary complex Kd; thus, the X-axis is given as [PAP]/Kd ternary. The plot demonstrates a pronounced, saturable binding-antisynergy between PAP and raloxifene, and virtually no interaction between PAP and DHEA - synergy was estimated at 1.1 (± 0.2). The fit predicts a 21-fold antisynergy (1.8 kcal/mole), which agrees well with the initial-rate value (23-fold or 2.0 kcal/mole). The close agreement of the equilibrium-binding and initial-rate affinity constants for all ligands and complexes argues that the ligand interactions during turnover are due primarily to ground-state interactions and that ligand-binding is near equilibrium during turnover.

Table 2.

Equilibrium Binding Constants

| Ligand | Enzyme Species | Kd (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| PAP | 1 E· | 20.30 (0.04) |

| PAPS | E· | 0.28 (0.03) |

| DHEA | E· | 1.0 (0.08) |

| Ral | E· | 1.1 (0.2) |

| PAP | DHEA·E· | 0.21 (0.05) |

| PAP | Ral·E· | 6.0 (0.7) |

| DHEA | PAP·E· | 1.1 (0.2) |

| Ral | PAP·E· | 29 (4) |

Dot indicates unoccupied binding site.

Parentheses enclose Standard Error estimates.

The kinetic mechanism of SULT2A1

The kinetic mechanism of SULT2A1 has not been determined; however, the mechanisms of other SULTS have been studied and are described as either ordered- or random-sequential (2, 41). The initial-rate pattern presented in Fig 2 is consistent with steady-state ordered or random mechanisms, and a random mechanism in which substrate binding is near equilibrium during turnover. The data argue against an ordered mechanism where binding of the first substrate is at equilibrium, which predicts double-reciprocal data that intersect on the vertical axis (42). The close agreement between the equilibrium-binding and initial-rate constants for all binary and ternary complexes strongly suggests that the binding reactions are near equilibrium during turnover. The results are not easily reconciled with a steady-state ordered mechanism. For example, the second substrate to add in the ordered mechanism would have to bind the enzyme nonproductively in the absence of the first. Such binding typically results in substrate inhibition with Ki equal to Kd, which is not observed. Further, the mechanism’s rate-constants would have to balance such that each of the steady-state affinity constants happened to equal their corresponding equilibrium-binding constants (including the non-productive binding constants) for both the raloxifene and DHEA reactions – an unlikely scenario. In summary, the data provide strong support only for the rapid-equilibrium random mechanism.

A molecular model of antisynergy

Crystal structures of SULT2A1 binary complexes offer a molecular explanation for the different response of the enzyme to DHEA and raloxifene. SULT2A1 harbors a 23-reside, conserved active-site “lid” (N226-D253) that restructures differently upon binding of donor or acceptor. SULT2A1 is the only sulfotransferase for which structures of both donor (1EFH) and acceptor binary complexes (1J99) are available (34–35, 43–44). The acceptor complexes show an open lid that accommodates binding of either DHEA or raloxifene, and both ligands dock well into the open structure in-silico (Materials and Methods). A nine-residue segment of the lid (N230-Y238) situated at the entrance of the acceptor binding-pocket repositions upon PAPS binding, with the result that the entrance is constricted to point that it will only admit DHEA – this too is supported by in-silico docking. Thus, the nine-residue segment appears to function as a molecular gate that restricts access to the acceptor site when “driven” into position by the binding of nucleotide. The open and closed positions of the gate are depicted in white and blue in Fig 4A and B. DHEA appears capable of forming a reactive complex with either form of the enzyme (Panel A) whereas raloxifene can only access the open form due to stearic hindrance from the PAP-stabilized, closed gate (Panel B).

Predictions of the Gate Model

The gate model predicts that substrates too large pass through the closed pore cannot bind to the enzyme; yet, initial-rate and equilibrium-binding measurements clearly demonstrate that raloxifene binds to the nucleotide-closed enzyme. The binding and structural data are reconciled if the enzyme is allowed to oscillate between open and closed forms when nucleotide is bound. In this case, the affinity of the large substrate will appear to decrease by a factor that corresponds to the fold-decrease in the concentration of the nucleotide-bound open form, which is given by the equilibrium constant for the isomerization between the open and closed states. This mechanism also predicts that the apparent change in affinity will be due exclusively to a change in the on-rate constant, because the origin of the effect is a simple decrease in the concentration of the open form. If, on-the-other-hand, an isomerization is not operative, the closed form seen in the crystal is not representative of the enzyme in solution, and antisynergy must be due to allosteric interactions that alter the form of the enzyme to which the acceptor binds. In such cases, changes in affinity can be caused by changes in on- and/or off-rate constants. Importantly, Microscopic Reversibility requires that allosteric interactions have identical energetic consequences for either ligand during binding; consequently, effects on the PAPS and raloxifene on- and off-rate constants should be identical. In contrast, a mechanism in which isomerization simply decreases the concentration of the acceptor-binding form of the enzyme makes no such prediction.

Testing the Predictions

To test the gate model, on- and off-rate constants for the binding of raloxifene to E and E·PAPS were determined. Binding was monitored via changes in intrinsic fluorescence of SULT2A1. Reactions were initiated by rapidly mixing a solution containing PAPS (200 μM) and SULT2A1 (0.20 μM) with an equal volume of a solution containing a fixed-variable concentration of raloxifene (Fig 5A and B). The PAPS concentration after mixing was high enough to saturate the ternary complex (23 × Km), and controls ensured that < 1.0 % of the E·PAPS complex hydrolyzed to E·PAP during the experiments. Conditions were such that < 2% of the total raloxifene was enzyme-bound at the reaction endpoint in all cases; hence, the reactions could be treated as pseudo-first order and fit using a single-exponential equation. The apparent rate constants obtained from the fits were plotted vs raloxifene concentration and the resulting plot was fit to a linear equation to obtain kon and koff (45) (Fig 5B).

Figure 5. Presteady state binding of RAL to SULT2A1.

(A) The binding of raloxifene to E. Binding reactions were initiated by rapidly (1:1) mixing a solution containing RAL (2.0 μM) with a solution containing SULT2A1 (0.10 μM). Binding was monitored by changes in intrinsic enzyme fluorescence (λex = 290 nm, λem ≥ 330 nm). Fluorescence changes are given relative to the intensity (I/I0) at t = 0. Each point represents the average of three independent determinations. The curve through the data represents the behavior predicted by the best fit to a single exponential model. Solution conditions: MgCl2 (5.0 mM), KPO4 (25 mM, pH 7.4), 25 ± 2 °C. (B) kobs vs [raloxifene]. Progress curves were obtained at four concentrations of raloxifene and conditions are given in (A). Reactions were pseudo-first order in raloxifene in all cases and apparent rate constants were obtained by fitting with a single exponential model. Similar studies were performed for the binding of DHEA and raloxifene to E and E·PAP. Results are compiled in Table 3.

The results of the presteady state binding studies are precisely those predicted by the isomerization mechanism - the effects of PAPS on raloxifene binding are virtually entirely due to changes in the on-rate constant (Table 3). The raloxifene on-rate constant decreases 19-fold when PAPS is bound, while the rate-constants for dissociation from raloxifene·E and raloxifene·E·PAPS are nearly identical. It should be noted that the dissociation constants for raloxifene binding to E and E·PAPS calculated from the rate constants (1.1 and 25 μM) agree well with the analogous initial-rate constants (1.1 and 23 μM), further confirming that ligand binding is near equilibrium during turnover.

Table 3.

Acceptor-Binding Rate Constants

| Ligand | Enzyme Species | kon (M−1 s−1) | koff s−1 | Kd (μM) (koff/kon) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DHEA | 1 E· | 22.0 (0.2) E+06 | 2.1 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) |

| DHEA | PAPS·E· | 2.1 (0.1) E+06 | 3.0 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) |

| Ral | E· | 4.1 (0.1) E+05 | 0.47 (0.03) | 1.4 (0.1) |

| Ral | PAPS·E· | 2.2 (0.3) E+04 | 0.54 (0.03) | 25 (5) |

Dot indicates unoccupied binding site.

Parentheses enclose Standard Error estimates.

The Gate is Non-Interactive

The initial-rate and equilibrium-binding measurements reveal that nucleotide has little if any influence on the affinity of DHEA, but do not rule out the possibility that the DHEA-binding on- and off-rate constants are affected equally by the nucleotide. If so, the gate interacts with DHEA during ingress and egress, and may have selective properties beyond “simple” sieving. If, on-the-other-hand, closing the gate does not influence the rate constants, it functions as a non-interactive molecular sieve that admits or prevents ligands on the basis of geometry. The data clearly show that DHEA-binding rate constants are not influenced significantly by the presence of PAPS (Table 4).

Table 4.

PAPS-Binding Rate Constants

| Ligand | Enzyme Species | kon (M−1 s−1) | koff s−1 | Kd (μM) (koff/kon) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAPS | 1 E· | 28.6 (0.5)1 E+06 | 2.3 (0.3) | 0.27 (0.06) |

| PAPS | DHEA·E· | 7.9 (0.4) E+06 | 1.9 (0.2) | 0.24 (0.09) |

| PAPS | RAL·E· | 8.3 (0.36) E+06 | 50 (2) | 6.0 (0.6) |

Dot indicates unoccupied binding site.

Parentheses enclose Standard Error estimates.

PAPS binding

Structures predict that raloxifene prevents the gate from closing (Fig 4). Consequently, the molecular circuitry that links PAPS binding to gate closure cannot be established, resulting in a 21-fold weakening in PAPS affinity. Weakened binding can be caused by changes in on- or off-rate constants. A decrease in on-rate constant reflects stabilization of structural features that inhibit binding, while an increased off-rate constant requires a weakening of the factors that prevent release. To better understand how different enzyme forms respond to nucleotide, the microscopic rate-constants for PAPS binding to E, E·DHEA and E·raloxifene were determined and compared.

Stopped-flow fluorescence was used to obtain PAPS-binding rate constants. Experimental protocols are detailed in Materials and Methods and closely resemble those used in the presteady-state binding experiments described above. Briefly, reactions were pseudo-first order in ligand, and progress curves were fit using a single-exponential model to obtain the apparent rate constants needed to determine kon and koff. PAPS binding to E·DHEA was studied under conditions where enzyme remained saturated with DHEA throughout the binding reactions. Saturation of the ternary complex with raloxifene is not possible due to its limited solubility (Ks = 55 μM (27)). Reactions involving raloxifene were initiated by mixing equal volumes of a solution containing PAPS (100 – 250 μM) and raloxifene (50 μM) with a solution containing SULT2A1 (50 nM) and raloxifene (50 μM). At 50 μM, raloxifene saturates E (50 × Kd) but not the ternary complex (~ 2 × Kd). Thus, prior to mixing with PAPS, enzyme is saturated with raloxifene. After mixing, raloxifene dissociates as the ternary complex forms, leading to an increase in fluoresence. The rate at which PAPS binds depends linearly on is concentration, while raloxifene dissociation is PAPS-concentration independent. Given the relatively slow rate at which raloxifene dissociates from the ternary complex (koff = 0.54 s−1), it was possible to increase the PAPS concentration and cleanly separate the PAPS-binding and DHEA-dissociation phases. A [PAPS]-optimized progress curve is shown in Fig 6A. The two phases are clearly identifiable, and the line through the data is the behavior predicted by a double-exponential fit. Panel B expands the time-axis of the data in the vicinity of the first phase to emphasize the separation. As expected, the rate constants associated with the first phase depend linearly on PAPS concentration and were used to obtain kon and koff, and the second-phase rate constant (0.51 ± 0.05 s−1) is independent of PAPS concentration and similar to the raloxifene ternary-complex koff, 0.54 s−1.

Figure 6. Presteady state binding of PAPS to SULT2A1·raloxifene.

(A) Progress curve for the binding of PAPS to E·raloxifene. A solution containing PAPS (100 μM) and raloxifene (50 μM) was mixed rapidly (1:1) with a solution containing SULT2A1 (0.05 μM) and raloxifene (50 μM). The raloxifene concentration (50 μM) is saturating with respect to the binary complex (45 × Kd) and subsaturating with respect to the ternary complex (2.0 × Kd). The addition of PAPS forms ternary complex (causing the early-phase decrease in signal) and initiates dissociation of raloxifene (causing the subsequent increase). PAPS concentrations were high enough to be pseudo-first order and to achieve good separation of the phases. Conditions: MgCl2 (5.0 mM), KPO4 (25 mM, pH 7.4), 25 ± 2 °C. Fluorescence was excited at 290 nm and detected above 330 nm using a cutoff filter. Each point represents the average of three independent determinations. The curve through the data is the behavior predicted by the best fit obtained using a double exponential model (see Materials and Methods). (B) Expanded view of Panel A. The time axis of the Panel A data is expanded to highlight the separation of PAPS-binding and raloxifene-dissociation reactions. The 100 μM PAPS used in this experiment was the lowest concentration used in constructing the kobs vs [PAPS] plot from which rate constants were obtained (Table 4).

The results of the PAPS-binding studies are compiled in Table 4. Remarkably, the on-rate constants for PAPS binding to E, E·DHEA and E·raloxifene are identical within error, indicating that the energetic, and presumably structural landscape experienced by PAPS as it binds to the enzyme is independent of ligand. Given that raloxifene prevents closure and DHEA does not, the identical on-rate constants suggest that binding and closure are separable. The off-rate constants for PAPS dissociation from PAPS·E and PAPS·E·DHEA are also identical within error (2.1 s−1); however, PAPS escape from the PAPS·E·raloxifene complex is 24-fold faster (50 s−1). In the closed enzyme, nucleotide is encapsulated by its binding pocket such that it can neither add to nor escape from the enzyme (Fig 7). Here again, the structure makes a testable prediction. If nucleotide escapes only from the open form, the isomerization equilibrium constant predicts that it will do so 21-fold more slowly from complexes that can close (PAPS·E and PAPS·E·DHEA) than from those that cannot (PAPS·E·raloxifene), which is precisely what is observed.

Figure 7. The closed structure encapsulates PAPS.

The active-site surface of the closed form of SULT2A1 is shown “wrapped” around the nucleotide. The limited access of nucleotide to solvent is highlighted by the dashed line circumscribing the only accessible solvent interface. Structural change is required to release the nucleotide.

In summary, “cap” closure is capable of encapsulating both substrates, but is allosterically linked only to the binding of nucleotide. Closure occurs in at least two, separable steps - nucleotide binding, and cap restructuring – and it is possible to trap the enzyme in an open complex in which the nucleotide has bound but cannot form the stabilizing linkages that couple binding to closure. Conversely, the binding of a large acceptor disrupts the allosteric linkages, opening the PAPS-binding pocket and allowing nucleotide to escape. Notably, PAPS concentrations in human tissue are reported to range from 10 – 80 μM (46–47). Thus, in its native milieu the enzyme is expected to be nucleotide-bound regardless of acceptor and the selectivity of the closed-gate will be maximally expressed.

Conclusions

The equivalence of initial-rate and equilibrium-binding constants of SULT2A1 substrates establishes that binding is random and near equilibrium during turnover and that substrates are selected, in significant measure, on the basis of antisynergy in ground-state binding interactions. Structures suggest that this selection is rooted in a nucleotide-driven restructuring of the acceptor-binding pocket that results in partial closure of an active-site pore that sieves substrates based on their dimensions. Reconciling the structural model with the binding data requires the nucleotide-bound form of the enzyme to isomerize between open and closed states, and that acceptors too large to pass through the pore will only bind the open form, while those small enough will bind both. This mechanism predicts that the concentration of the open form will be reduced when nucleotide is bound by a factor give by the isomerization equilibrium constant. Consequently, the large-substrate affinity constants will appear to decrease by the same factor despite the fact the affinity for the open form has not changed. A further consequence of the reduced concentration is that the effects on binding will appear to be due exclusively to changes in the on-rate constant, and the binding and on-rate constant effects will be equivalent. These predictions are well supported by the experimental results and suggest that this molecular sieving mechanism is germane to SULT2A1 substrate selection and possibly that of other cytosolic sulfotransferases.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants GM389532 and GM544691

Abbreviations

- DHEA

5-dehydroepiandrosterone

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- GSH

glutathione

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- HEPES

N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid

- IPTG

isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside

- LB

Luria broth

- MBP

maltose binding protein

- PAP

3′, 5′-diphosphoadenosine

- PAPS

3′-phosphoadinosine 5′-phosphosulfate

- PMSF

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

- raloxifene

[6-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)- benzothiophen-3-yl]-[4-[2-(1-piperidyl)ethoxy]phenyl] –methanone

- SULT

cytosolic sulfotransferase

References

- 1.Bai Q, Xu L, Kakiyama G, Runge-Morris MA, Hylemon PB, Yin L, Pandak WM, Ren S. Sulfation of 25-hydroxycholesterol by SULT2B1b decreases cellular lipids via the LXR/SREBP-1c signaling pathway in human aortic endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. 2011;214:350–356. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang H, Varlamova O, Vargas FM, Falany CN, Leyh TS. Sulfuryl transfer: the catalytic mechanism of human estrogen sulfotransferase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10888–10892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.10888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parker CR. Dehydroepiandrosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate production in the human adrenal during development and aging. Steroids. 1999;64:640–647. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(99)00046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsubayashi Y, Sakagami Y. Peptide hormones in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:649–674. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein DS, Swoboda KJ, Miles JM, Coppack SW, Aneman A, Holmes C, Lamensdorf I, Eisenhofer G. Sources and physiological significance of plasma dopamine sulfate. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:2523–2531. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.7.5864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Visser TJ. Role of sulfation in thyroid hormone metabolism. Chem Biol Interact. 1994;92:293–303. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(94)90071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selvan RS, Ihrcke NS, Platt JL. Heparan sulfate in immune responses. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;797:127–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb52955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tangemann K, Bistrup A, Hemmerich S, Rosen SD. Sulfation of a high endothelial venule-expressed ligand for L-selectin. Effects on tethering and rolling of lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1999;190:935–942. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.7.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson JA, Fredenburgh JC, Stafford AR, Guo YS, Hirsh J, Ghazarossian V, Weitz JI. Hypersulfated low molecular weight heparin with reduced affinity for antithrombin acts as an anticoagulant by inhibiting intrinsic tenase and prothrombinase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9755–9761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010048200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stowers L, Logan DW. Sexual dimorphism in olfactory signaling. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:770–775. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mesiano S, Jaffe RB. Developmental and functional biology of the primate fetal adrenal cortex. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:378–403. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.3.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falany JL, Macrina N, Falany CN. Regulation of MCF-7 breast cancer cell growth by beta-estradiol sulfation. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;74:167–176. doi: 10.1023/a:1016147004188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falany JL, Falany CN. Regulation of estrogen sulfotransferase in human endometrial adenocarcinoma cells by progesterone. Endocrinology. 1996;137:1395–1401. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.4.8625916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steventon GB, Heafield MT, Waring RH, Williams AC. Xenobiotic metabolism in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1989;39:883–887. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.7.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li L, Falany CN. Elevated hepatic SULT1E1 activity in mouse models of cystic fibrosis alters the regulation of estrogen responsive proteins. J Cyst Fibros. 2007;6:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore KL. The biology and enzymology of protein tyrosine O-sulfation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24243–24246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R300008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kase ET, Andersen B, Nebb HI, Rustan AC, Thoresen GH. 22-Hydroxycholesterols regulate lipid metabolism differently than T0901317 in human myotubes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:1515–1522. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falany CN. Enzymology of human cytosolic sulfotransferases. Faseb J. 1997;11:206–216. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.4.9068609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blanchard RL, Freimuth RR, Buck J, Weinshilboum RM, Coughtrie MW. A proposed nomenclature system for the cytosolic sulfotransferase (SULT) superfamily. Pharmacogenetics. 2004;14:199–211. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200403000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teubner W, Meinl W, Florian S, Kretzschmar M, Glatt H. Identification and localization of soluble sulfotransferases in the human gastrointestinal tract. Biochem J. 2007;404:207–215. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riches Z, Stanley EL, Bloomer JC, Coughtrie MW. Quantitative evaluation of the expression and activity of five major sulfotransferases (SULTs) in human tissues: the SULT “pie”. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:2255–2261. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.028399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Comer KA, Falany JL, Falany CN. Cloning and expression of human liver dehydroepiandrosterone sulphotransferase. Biochem J. 1993;289(Pt 1):233–240. doi: 10.1042/bj2890233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dong D, Ako R, Wu B. Crystal structures of human sulfotransferases: insights into the mechanisms of action and substrate selectivity. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2012 doi: 10.1517/17425255.2012.677027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Falany CN, Wheeler J, Oh TS, Falany JL. Steroid sulfation by expressed human cytosolic sulfotransferases. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1994;48:369–375. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(94)90077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Labrie F. Intracrinology. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1991;78:C113–118. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(91)90116-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindsay J, Wang LL, Li Y, Zhou SF. Structure, function and polymorphism of human cytosolic sulfotransferases. Curr Drug Metab. 2008;9:99–105. doi: 10.2174/138920008783571819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snyder KR, Sparano N, Malinowski JM. Raloxifene hydrochloride. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2000;57:1669–1675. quiz 1676–1668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jordan VC. SERMs: meeting the promise of multifunctional medicines. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:350–356. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Falany JL, Pilloff DE, Leyh TS, Falany CN. Sulfation of raloxifene and 4-hydroxytamoxifen by human cytosolic sulfotransferases. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:361–368. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.006551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Falany CN, Vazquez ME, Kalb JM. Purification and characterization of human liver dehydroepiandrosterone sulphotransferase. Biochem J. 1989;260:641–646. doi: 10.1042/bj2600641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brzozowski AM, Pike AC, Dauter Z, Hubbard RE, Bonn T, Engstrom O, Ohman L, Greene GL, Gustafsson JA, Carlquist M. Molecular basis of agonism and antagonism in the oestrogen receptor. Nature. 1997;389:753–758. doi: 10.1038/39645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heroux JA, Falany CN, Roth JA. Immunological characterization of human phenol sulfotransferase. Mol Pharmacol. 1989;36:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cubitt HE, Houston JB, Galetin A. Prediction of human drug clearance by multiple metabolic pathways: integration of hepatic and intestinal microsomal and cytosolic data. Drug Metab Dispos. 2011;39:864–873. doi: 10.1124/dmd.110.036566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rehse PH, Zhou M, Lin SX. Crystal structure of human dehydroepiandrosterone sulphotransferase in complex with substrate. Biochem J. 2002;364:165–171. doi: 10.1042/bj3640165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pedersen LC, Petrotchenko EV, Negishi M. Crystal structure of SULT2A3, human hydroxysteroid sulfotransferase. FEBS Lett. 2000;475:61–64. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01479-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cook IT, Leyh TS, Kadlubar SA, Falany CN. Structural Rearrangment of SULT2A1: effects on dehydroepiandrosterone and raloxifene sulfation. Horm Mol Biol Clin Invest. 2010;1 doi: 10.1515/HMBCI.2010.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun M, Leyh TS. The human estrogen sulfotransferase: a half-site reactive enzyme. Biochemistry. 2010;49:4779–4785. doi: 10.1021/bi902190r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andreassi JL, Leyh TS. Molecular functions of conserved aspects of the GHMP kinase family. Biochemistry. 2004;43:14594–14601. doi: 10.1021/bi048963o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eswar N, Webb B, Marti-Renom MA, Madhusudhan MS, Eramian D, Shen MY, Pieper U, Sali A. Comparative protein structure modeling using Modeller. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2006;Chapter 5(Unit 5):6. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0506s15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verdonk ML, Chessari G, Cole JC, Hartshorn MJ, Murray CW, Nissink JW, Taylor RD, Taylor R. Modeling water molecules in protein-ligand docking using GOLD. J Med Chem. 2005;48:6504–6515. doi: 10.1021/jm050543p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tyapochkin E, Cook PF, Chen G. Isotope exchange at equilibrium indicates a steady state ordered kinetic mechanism for human sulfotransferase. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11894–11899. doi: 10.1021/bi801211t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cleland WW. Steady state kinetics. In: Boyer PD, editor. The Enzymes Student Edition. Academic Press; New York: 1970. pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu LY, Hsieh YC, Liu MY, Lin YH, Chen CJ, Yang YS. Identification and characterization of two amino acids critical for the substrate inhibition of human dehydroepiandrosterone sulfotransferase (SULT2A1) Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:660–668. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.041038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang HJ, Shi R, Rehse P, Lin SX. Identifying androsterone (ADT) as a cognate substrate for human dehydroepiandrosterone sulfotransferase (DHEA-ST) important for steroid homeostasis: structure of the enzyme-ADT complex. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2689–2696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310446200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson K. Transient-state kinetic analysis of enzyme reaction pathways. In: Sigman DS, editor. The Enzymes. Academic Press; New York: 1992. pp. 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu Z, Wood TC, Adjei AA, Weinshilboum RM. Human 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate synthetase: radiochemical enzymatic assay, biochemical properties, and hepatic variation. Drug Metab Dispos. 2001;29:172–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klaassen CD, Boles JW. Sulfation and sulfotransferases 5: the importance of 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) in the regulation of sulfation. Faseb J. 1997;11:404–418. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.6.9194521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cleland WW. Statistical analysis of enzyme kinetic data. Methods Enzymol. 1979;63:103–138. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)63008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]