Abstract

The HIV-1 epidemic in Russia has been insufficiently studied, with only 11 complete genome sequences from this country currently available, only three of which are of the locally predominant genetic form, the former Soviet Union (FSU) subtype A variant (AFSU). Here we analyze 10 newly derived AFSU near full-length genome sequences from Russia. Samples were selected based on phylogenetic clustering in protease-reverse transcriptase in two of the major AFSU clusters, V77IPR (n=6), widely circulating in Russia and other FSU countries, and ASP1 (n=4), predominant in St. Petersburg. The phylogenetic analysis shows that the V77IPR genomes group in a monophyletic cluster together with 10 previously obtained AFSU genome sequences from Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Cyprus, all bearing the V77I substitution in protease. Similarly, the four ASP1 genomes group in a monophyletic cluster. These results therefore show that the monophyly of V77IPR and ASP1 AFSU clusters is supported in near complete genomes.

The HIV-1 epidemic in Eastern European and Central Asian countries formerly part of the Soviet Union is dominated by a subtype A monophyletic variant1,2 of Central African origin that, after an initial limited propagation via heterosexual contact,3,4 began spreading explosively among injecting drug users (IDU) in the Ukrainian seaport city of Odessa in early 1995.5 This variant is the predominant HIV-1 genetic form in all former Soviet Union (FSU) countries studied except in Estonia, and for this reason it is often referred to as the AFSU variant. The number of people infected with HIV-1 in Eastern European and Central Asian countries where the AFSU variant is circulating was estimated to be approximately 1.4 million at the end of 2009.6

The greatest burden of the epidemic in this region is in the Russian Federation with 980,000 estimated cases at the end of 2009 (the third largest number of HIV-1-infected people among non-African countries after India and the United States) and a prevalence of 1%, followed by Ukraine, with 350,000 estimated cases and a 1.1% prevalence. In spite of its magnitude, the HIV-1 epidemic in FSU countries has been insufficiently studied from a genetic point of view. Thus, at the Los Alamos HIV Sequence database, only 3948 HIV-1 sequences from FSU countries are available, which is very low compared to those from Western and Central Europe, with 81,757 sequences for an estimated number of 820,000 infections, North America, with 126,795 sequences for 1.5 million estimated infections, and South and Central America, with 21,957 sequences for 1.4 million estimated infections.7 The number of HIV-1 full-length or near full-length genome sequences available from FSU countries follows a similar trend, with only 47 sequences available from these countries, compared to 438 from Western and Central Europe, 622 from North America, and 242 from South and Central America. Considering HIV-1 isolates from Russia, only 11 near full-length genome sequences are available, only three of which are from the AFSU variant, which represents more than 90% HIV-1 infections in the country.2

The scarcity of available near full-length HIV-1 genome sequences from Russia was one of the main motivations of the current study. Another was an interest in analyzing near full-length genomes of two of the major AFSU monophyletic clusters in which this variant is subdivided, previously analyzed in partial sequences, one of them designated V77IPR, due the presence of the characteristic V77I substitution in protease,8 widely circulating in Russia (nearly half of HIV-1 infections2) and other FSU countries, and the other ASP1, which represents approximately 56% of HIV-1 infections in St. Petersburg,9 the second largest city in Russia and one of the cities most heavily affected by the HIV-1 epidemic.10

Plasma samples used for this study were collected from 2002 through 2008 in different cities of Russia from individuals belonging to diverse risk categories. Samples were selected for near full-length genome amplification and sequencing based on analyses of protease-reverse transcriptase (PR-RT) sequences showing their clustering in the V77IPR or ASP1 AFSU clusters.2,9 Near full-length genomes were amplified from plasma RNA in four overlapping segments by RT-PCR and sequenced as previously described.11,12 Electropherograms were assembled with SeqMan (DNASTAR, Madison, WI). Sequences were aligned with MAFFT v.6.13 Highly polymorphic segments with uncertain alignments due to variable length polymorphisms were removed for phylogenetic analyses.

Phylogenetic sequence analyses were done via maximum likelihood using RAxML.14 The substitution model used for this analysis was the general time reversible with CAT approximation for among-sites rate heterogeneity (GTR+CAT). Genomes were analyzed for the possible presence of intersubtype recombination by bootscanning using SimPlot v3.5.15 For this analysis, a window of 300 nucleotides was used, moving in 20 nucleotide increments, and trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining algorithm and Kimura two-parameter distances. Protein sequences were analyzed using the Gene Cutter program.7

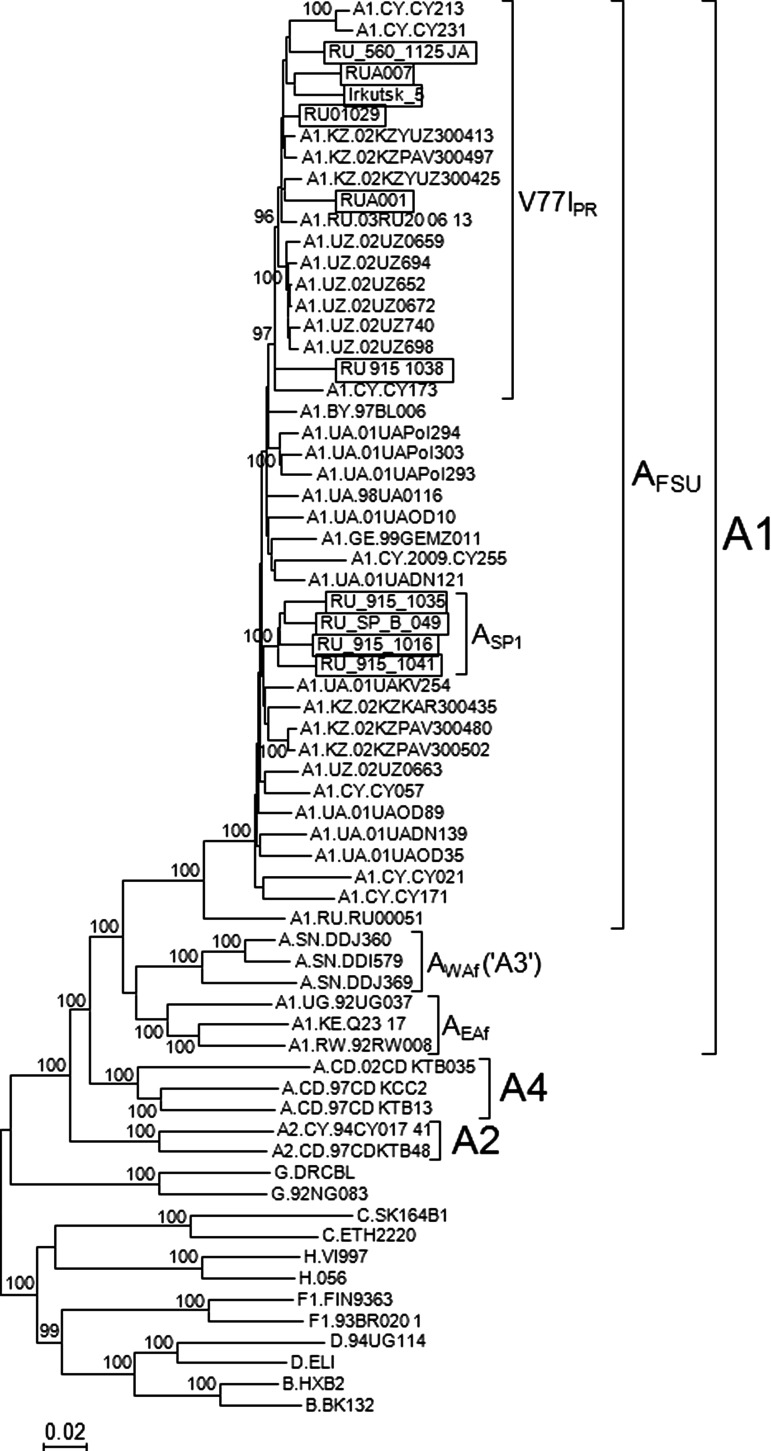

Near full-length genome sequences (8.8–9 kb) were obtained in 10 samples, six of the V77IPR cluster and four of the ASP1 cluster. Epidemiological data of these samples are shown in Table 1. All 10 newly derived sequences had intact Gag, Pol, Vif, Vpr, Tat, Rev, Vpu, Env, and Nef open reading frames. In bootscan analyses all were uniformly of subtype A along their genomes (results not shown). In the maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis, in which all near full-length genome AFSU sequences available at the Los Alamos HIV Sequence Database7 (including seven from Cyprus, presumably from Eastern European individuals residing in this country16,17) were included, all newly derived sequences clustered with the other AFSU viruses (Fig. 1). Within the AFSU clade, the genomes of the four viruses previously classified in the ASP1 cluster, based on PR-RT sequences, formed a strongly supported (100% bootstrap value) cluster, and the newly derived near full-length V77IPR sequences formed another strongly supported (97% bootstrap value) cluster together with 13 previously obtained genome sequences from Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Cyprus, with two of the sequences, RU_915_1038 and CY173, branching basally to all others in the cluster, which formed a subcluster supported by a 96% bootstrap value (Fig. 1). [It must be noted that monophyletic clustering of the viruses of the V77IPR subvariant required removal of one of the sequences from Russia downloaded from the Los Alamos Database, PokA1Rus, a probable intrasubtype recombinant between V77IPR and non-V77IPR AFSU viruses; the inclusion of this sequence in the phylogenetic analyses caused a decline in the bootstrap support of the V77IPR cluster to 45% (results not shown).]

Table 1.

Epidemiological Data of Samples Used in this Study

| Virus name | City of sample collection | Gender | Transmission route/risk factor | Year of HIV diagnosis | Year of sample collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RU_915_1016 | St. Petersburg | F | IDU | 2001 | 2006 |

| RU_915_1035 | St. Petersburg | F | IDU | n.a | 2006 |

| RU_915_1038 | St. Petersburg | F | IDU | 2002 | 2006 |

| RU_915_1041 | St. Petersburg | F | Heterosexual | n.a. | 2006 |

| RU_SP_B_049 | St. Petersburg | M | IDU | n.a. | 2006 |

| RU01029 | Novy Urengoy | n.a. | Heterosexual | 2001 | 2002 |

| RU_560_1125_JA | Novy Urengoy | M | Bisexual | 2005 | 2005 |

| Irkutsk_5 | Irkutsk | M | IDU | 2003 | 2007 |

| RUA001 | Odintsovo, Moscow Oblast | M | Heterosexual | 2008 | 2008 |

| RUA007 | Pushkino, Moscow Oblast | M | Heterosexual | 2008 | 2008 |

IDU, injecting drug user; n.a., not available.

FIG. 1.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of HIV-1 near full-length genome sequences of the AFSU variant. Names of newly derived sequences are boxed. Only bootstrap values ≥90% are shown. EAf and WAf denote A1 subsubtype variants of East and West Africa, respectively (the West African variant is designated by some authors as subsubtype A318). Countries of sample collection of subtype A viruses retrieved from the Los Alamos Database are shown before the isolate's name using the ISO two-letter country codes: AZ, Azerbaijan; BY, Belarus; CD, Democratic Republic of Congo; CY, Cyprus; GE, Georgia; KE, Kenya; KZ, Kazakhstan; SN, Senegal; RU, Russia; RW, Rwanda; UA, Ukraine; UG, Uganda; UZ, Uzbekistan.

Within the V77IPR subvariant the viruses from Uzbekistan formed a local subcluster, supporting a single introduction of this subvariant in Uzbekistan (Fig. 1). It is interesting to note that none of 10 sequences from Ukraine branched in the V77IPR cluster. This was also the case when PR-RT sequences retrieved from the Los Alamos Database were analyzed (results not shown). This may be explained by the fact that the HIV-1 subtype A epidemic of Ukraine may derive from a radiation predating the emergence of the V77IPR variant in 1997 in Russia.8 The phylogenetic tree also revealed that the three subtype A viruses from Senegal previously assigned to the A3 subsubtype18 formed a cluster fully branching within the subsubtype A1 radiation, together with the AFSU and East African variants, supporting the notion that the viruses classified by some authors as an A3 subsubtype in fact represent a West African variant of the A1 subsubtype.

The common ancestry of the V77IPR viruses, on the one hand, and of ASP1 viruses, on the other, was also supported by the presence of highly characteristic amino acid residues and nucleotides that are absent or rare in AFSU viruses branching outside of the clusters mentioned. Signature amino acid residues of each cluster, here defined as those present in ≥75% viruses within the corresponding cluster and in ≤10% AFSU viruses outside of them, were, for V77IPR, protease 77I, RT 35I and 62V, Tat 68L, Env 158T, and Nef 151E; and for the ASP1 viruses Vif 73Q, Tat 86K and 73S, Env 92E, and Nef 87F (amino acid residues are numbered as in the NL4-3 isolate). It should be noted that one of the viruses of the V77IPR cluster, RUA007, lacks the V77I substitution in protease. However it contains two additional signature RT amino acid residues of this cluster, 33I and 62V. These two residues are absent from the two viruses branching in a basal position within the V77IPR cluster, RU_915_1038 and CY173, which, however, contain the V77I substitution.

Signature nucleotides in synonymous positions of the PR-RT fragment commonly analyzed for drug resistance-associated mutations were also similarly defined for the V77IPR cluster. These are nucleotides at the third position of protease codons 38 (G) and of RT codons 66 (A), 67 (T), 149 (C), and 246 (A). For the ASP1 viruses, five synonymous substitutions at RT codons 40, 42, 48, 144, and 160 were previously defined as characteristic of this cluster, with the presence of ≥3 of these nucleotides being 100% predictive for clustering within the ASP1 clade.9

To analyze the possibility of intrasubtype recombination, genome fragments of 2 kb moving in 500 nucleotide increments were phylogenetically analyzed via maximum likelihood. No evidence of tree topology incongruence between genome fragments was found in any of the newly derived sequences (results not shown).

In summary, we have obtained 10 new HIV-1 near full-length genome sequences of AFSU viruses from Russia, which almost equals the number of all previously available HIV-1 near full-length genomes from this country. The analyses of these sequences support the monophyly of two major AFSU clusters previously defined in PR-RT, V77IPR and ASP1, which represent a large proportion of HIV-1 isolates circulating in Russia and in the city of St. Petersburg, respectively. These results may contribute to a better knowledge of the propagation of HIV-1 variants in Russia and other FSU countries and may serve as a basis for the study of the correlations of these phylogenetically defined variants with biological properties and with susceptibility to immune responses relevant for the design of vaccine immunogens intended for use in these countries.

Acknowledgments

We thank the personnel at the Genomic Unit, Centro Nacional de Microbiología, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, for technical assistance in sequencing. This work was funded by WHO-UNAIDS through agreement for performance of work 2011/120936-0, which was partially funded by Office of AIDS Research, National Institutes of Health, USA. Sequences have been deposited in GenBank under accessions JQ292891–JQ292900.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Bobkov A. Cheingsong-Popov R. Selimova L, et al. An HIV type 1 epidemic among injecting drug users in the former Soviet Union caused by a homogeneous subtype A strain. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1997;13:1195–1201. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vázquez de Parga E. Rakhmanova A. Pérez-Álvarez L, et al. Analysis of drug resistance-associated mutations in treatment-naive individuals infected with different genetic forms of HIV-1 circulating in countries of the former Soviet Union. J Med Virol. 2005;77:337–344. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Novitsky VA. Montano MA. Essex M. Molecular epidemiology of an HIV-1 subtype A subcluster among injection drug users in the Southern Ukraine. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1998;14:1079–1085. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomson MM. Vázquez de Parga E. Vinogradova A, et al. New insights into the origin of the HIV type 1 subtype A epidemic in former Soviet Union countries derived from sequence analyses of preepidemically transmitted viruses. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007;23:1599–1604. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nabatov AA. Kravchenko ON. Lyulchuk MG, et al. Simultaneous introduction of HIV type 1 subtype A and B viruses into injecting drug users in southern Ukraine at the beginning of the epidemic in the former Soviet Union. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2002;18:891–895. doi: 10.1089/08892220260190380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.UNAIDS: Report on the global AIDS epidemic 2010. http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/documents/20101123_GlobalReport_full_en.pdf http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/documents/20101123_GlobalReport_full_en.pdf

- 7.HIV Sequence Database: Los Alamos National Laboratory. http://www.hiv-lanl.gov http://www.hiv-lanl.gov

- 8.Roudinskii NI. Sukhanova AL. Kazennova EV, et al. Diversity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype A and CRF03_AB protease in Eastern Europe: Selection of the V77I variant and its rapid spread in injecting drug user populations. J Virol. 2004;78:11276–11287. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11276-11287.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomson MM. Vinogradova A. Delgado E, et al. Molecular epidemiology of HIV-1 in St. Petersburg, Russia: Predominance of subtype A, former Soviet Union variant, and identification of intrasubtype subclusters. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51:332–339. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31819c1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zagdyn Z. Kovelenov A. Semikova S, et al. Spread of HIV infection in Leningrad oblast during 1999–2009. Euro Surveill. 2011;16:121–130. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delgado E. Thomson MM. Villahermosa ML, et al. Identification of a newly characterized HIV-1 BG intersubtype circulating recombinant form in Galicia, Spain, which exhibits a pseudotype-like virion structure. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29:536–543. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200204150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sierra M. Thomson MM. Ríos M, et al. The analysis of near full-length genome sequences of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 BF intersubtype recombinant viruses from Chile, Venezuela and Spain reveals their relationship to diverse lineages of recombinant viruses related to CRF12_BF. Infect Genet Evol. 2005;5:209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katoh K. Toh H. Recent developments in the MAFFT multiple sequence alignment program. Brief Bioinform. 2008;9:286–298. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbn013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stamatakis A. Hoover P. Rougemont J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML Web servers. Syst Biol. 2008;57:758–771. doi: 10.1080/10635150802429642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lole KS. Bollinger RC. Paranjape RS, et al. Full-length human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes from subtype C-infected seroconverters in India, with evidence of intersubtype recombination. J Virol. 1999;73:152–160. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.152-160.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kousiappa I. Van De Vijver DA. Kostrikis LG. Near full-length genetic analysis of HIV sequences derived from Cyprus: Evidence of a highly polyphyletic and evolving infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2009;25:727–740. doi: 10.1089/aid.2008.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kousiappa I. Achilleos C. Hezka J, et al. Molecular characterization of HIV type 1 strains from newly diagnosed patients in Cyprus (2007–2009) recovers multiple clades including unique recombinant strains and lack of transmitted drug resistance. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2011;27:1183–1199. doi: 10.1089/aid.2011.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meloni ST. Kim B. Sankalé JL, et al. Distinct human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype A virus circulating in West Africa: Sub-subtype A3. J Virol. 2004;78:12438–12445. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12438-12445.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]