Abstract

Background/Objective

To determine whether a home-based multi-component physical activity counseling (PAC) intervention is effective in reducing glycemic measures in older prediabetic outpatients.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Controlled clinical trial of 302 overweight (body mass index 25–45 kg/m2), older (ages 60–89) outpatients with impaired glucose tolerance (fasting blood glucose 100–125 mg/dL, HbA1c <7%), randomly assigned to a PAC intervention group (n=180), compared to a Usual Care (UC) control group (n=122) and recruited through primary care clinics of the Durham VA Medical Center between September 29, 2008 and March 25, 2010.

Intervention

A 12 month, home-based multi-component PAC program including one in-person baseline counseling session, regular telephone counseling, physician endorsement in clinic with monthly automated encouragement, and tailored mailed materials. All study participants, including UC, received a consult to a VA weight management program.

Measurements

The primary outcome was HOMA-IR, calculated from fasting insulin and glucose levels at baseline, 3 and 12 months. Hemoglobin A1C was the secondary indicator of glycemic control. Other secondary outcomes included anthropometric measures, and self-reported physical activity, health-related quality of life, and physical function.

Results

There were no significant differences between the PAC or Usual Care groups over time for any of the glycemic indicators. Both groups had small declines over time of approximately 6% in fasting blood glucose, p< 0.001, while other glycemic indicators remained stable. The declines in glucose were not sufficient to affect the change in HOMA-IR scores due to fluctuations in insulin over time. Endurance physical activity increased significantly in PAC group, P<0.001 compared to UC.

Conclusion

Home-based telephone counseling increased physical activity levels but was insufficient for improving glycemic indicators among older prediabetic outpatients.

Keywords: Diabetes, Aging, Randomized Clinical Trial, Counseling, Physical Activity, Veterans, Obesity

INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetes is reaching epidemic proportions in this country, paralleling increases in overweight and obesity. About 11 million older adults in the United States have diabetes. Diabetes is the leading cause of new cases of blindness, kidney failure, and non-traumatic limb amputation in the United States. An estimated 79 million people In the United States are considered to have prediabetes.1

Type 2 diabetes often can be prevented with lifestyle modifications. This is particularly true among older adults. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) showed that an intervention advocating weight loss and physical activity reduced the development of diabetes by about 71% in adults over age 60.2 Subsequent research has confirmed the independent benefit of physical activity in preventing diabetes after controlling for weight loss.3 However, the direct costs of lifestyle interventions such as the DPP may be prohibitive. Alternative approaches, involving telephone counseling and mailed interventions may provide a comparable intervention effect with greater outreach for older adults not able to attend facility-based interventions, and at a lower cost.

Our research program to date has focused on delivery of home-based physical activity and/or lifestyle interventions for older adults.4,5 Given the findings from the DPP that older adults experienced significantly reduced development of type 2 diabetes with a lifestyle intervention,2 we developed a home-based physical activity counseling (PAC) intervention trial aimed at improving glycemic indicators among older Veterans. The Enhancing Fitness in Older Overweight Veterans with Impaired Glucose Tolerance (Enhanced Fitness) trial is a randomized controlled trial with an adaptive randomization design that tested the effects of a one-year home-based physical activity telephone counseling intervention compared to a Usual Care (UC).

METHODS

Study Design

The Enhanced Fitness trial was originally designed as an adaptive randomization design with allocation to PAC or UC. Adaptive design studies identify intermediate markers of response to treatment and re-randomize, at a predetermined time point, to additional or alternate therapies based on responses to initial treatment.6 The design initially included an interim 3-month assessment of physical activity uptake with a planned reassignment to more or less counseling based on progress towards achievement of prescribed physical activity goals. The protocol was amended to eliminate the allocation to added cognitive behavioral therapy for non-adherence when one-third of the sample had been accrued and no study participants met the pre-defined objective parameters for non-adherence. Non-adherence was defined as failing to meet up to 75% of the exercise prescription, in minutes per week, that was agreed upon between the health counselor and patient during the counseling sessions. Thus, all participants in the PAC group were reallocated to higher or lower doses of telephone follow-up at three months. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Durham VA institutional review board annually.

Study Participants

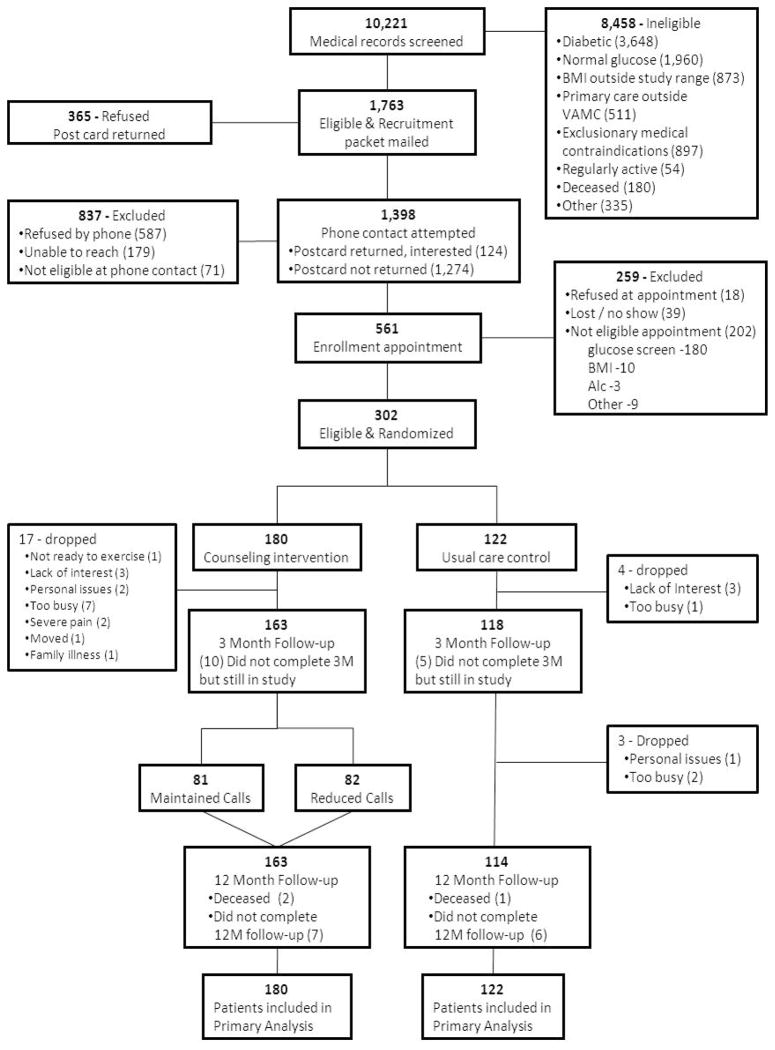

Figure 1 depicts the screening and enrollment process. The medical records of all age eligible (60 and over) patients from the Durham and Raleigh VA clinics (n= 10,221) were pre-screened by our research staff. Eligible patients were required to be followed by a primary care provider (PCP) in VA Primary Care, Geriatrics or Women’s Health clinics and have at least one visit in the previous 12 months. They had to have impaired glucose tolerance defined as a fasting glucose between 100–125 mg/dl, be free from a diagnosis of diabetes, have a Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) below 7%, and not be on diabetes medications. A body mass index (BMI) between 25 and 45 kg/m2 was required. Other exclusion criteria, described previously,7 assessed overall health for safe participation in this study. Individuals who exceeded current physical activity recommendations were excluded.8 A total of 8443 individuals did not meet initial eligibility criteria with another 15 excluded by the PCP. Recruitment packages were mailed to 1763 patients. Of these, 1398 were contacted by telephone, and enrollment appointments were made for 561 potentially eligible patients. From this group, a total of 302 patients met full eligibility criteria and were randomized between September 29, 2008 and March 25, 2010. A statistician with no participant contact delivered sealed randomization assignments to the project coordinator. These were kept in a locked cabinet until randomization occurred.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram for clinical trial

Due to the adaptive design individuals were not equally allocated to groups. Thus, a priori, patients were allocated so that approximately 60% of the sample was in the intervention arm (81 received monthly follow-up telephone calls; 82 received monthly follow-up calls during months 3–6 and then every other month during months 6–12), and 40% of the sample (122) was in UC.

Procedures

All of the outcomes were assessed at baseline, three months and 12 months by individuals blinded to intervention status. Each visit followed a structured format that lasted approximately 90 minutes.

Enhanced Fitness Intervention

The Enhanced Fitness Intervention was designed to enhance self-efficacy for physical activity by integrating self-monitoring, goal setting, reinforcement, modeling, and cognitive reframing into an ongoing personally tailored counseling program of physical activity for endurance and strengthening activities.9 Consistent with recommendations from the American Diabetes Association,10 the American College of Sports Medicine, the American Heart Association,8 and the U.S. Physical Activity Guidelines,11 each individual was given the long-term goal of engaging in 30 or more minutes of lower extremity aerobic exercise, preferably walking, on five or more days of the week, and 15 minutes of exercises to increase lower extremity strength on three non-consecutive days each week.

The intervention has been described previously.7,12 (1) Individuals assigned to the PAC arm received an in-person baseline counseling consultation with a trained health counselor. Using a structured protocol, the counselor assessed current activity status and established a realistic two-week physical activity prescription. Individuals were given a notebook containing handouts on the health benefits of exercise, tips for exercising safely, a poster with specific exercises, elastic bands of different resistances, and a pedometer. (2) The baseline counseling was supplemented with regular telephone counseling every two weeks for six weeks followed by monthly calls over the entire one-year intervention period. Individuals assigned to reduced telephone calls received telephone calls every other month during the final six months. (3) To enhance partnership with primary care, the PCP endorsed physical activity and/or involvement in the study at the next clinic visit. (4) This was followed by regular PCP encouragement using an automated telephone system. (5) The final component of the intervention was a quarterly personally tailored feedback report which summarized progress towards each long term goal of endurance and strengthening exercise.

Usual Care plus MOVE!®

Participants randomized to the Usual Care group received the standard of care as provided in their usual VA primary, women’s health, or geriatric clinic. Physical activity counseling within the context of a clinic visit varies considerably by provider; with some providers endorsing physical activity routinely with each visit while others do not. In addition to provider discretionary approaches to care, VA also has a nationally mandated weight management program for Veterans called MOVE!®. This program offers various levels of support for Veterans desiring to lose weight, is voluntary, and includes interactive self-management programs, classroom sessions and individualized counseling. MOVE!® provides guidance on nutrition and physical activity using a step-level approach coupled with individualized goal setting. Therefore, each patient enrolled in the study was informed at randomization, that they would be referred to the MOVE!® program Once a consult was submitted, MOVE!® personnel would send each patient a lifestyle questionnaire and it was up to the individual to decide whether or not they would participate in the various MOVE!® activities offered at our VA. Participation in MOVE!® was tracked by our study.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was change in insulin action between groups as measured by fasting insulin and glucose levels, using the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) with HbA1C as a secondary indicator of improved glycemic control. Patients were instructed to refrain from eating or drinking anything, except for water and medications, past midnight the evening before their appointment. A reminder call was placed the night before the scheduled appointment and fasting was verified by study personnel before proceeding with appointed blood draws. Blood chemistries which also included lipids were, except for fasting insulin, analyzed at the VA central laboratory by technicians not affiliated with the study. Blood samples for measurement of fasting insulin were sent to a private laboratory

Secondary outcomes included self-reports of physical activity, health-related quality of life, and physical function. Physical activity was assessed with a modified version of the Community Healthy Activities Model Program for Seniors (CHAMPS) questionnaire.13 The CHAMPS was specifically developed for older adults, has good construct validity and reliability, and is sensitive to change.14 Our modification consisted of an of exclusion self-reports of heavy household work or heavy gardening from our calculations of total moderate minutes of endurance physical activity per week due to previous experience with substantial over reporting in these activities. Health related quality of life was measured using the Short-Form-36 Medical Outcomes Study (SF-36) questionnaire.15 The SF-36 is a widely used measure of general health and function that has been validated across many populations and considered a reliable indicator of health status and is also sensitive to change.16,17

Other items collected on the questionnaires included baseline assessment of race, ethnicity, and education level. Race and ethnicity was determined by self-report of the patients during the baseline questionnaire using the following categories: Caucasian, African-American, Hispanic or Other. At each wave of data collection we also assessed chronic conditions using the Older Americans Resources and Services (OARS) Comorbidity and Symptom Index.18 The OARS ascertains either an affirmative or negative response to unique medical conditions and symptoms.

Statistical Analyses

The sample size was set at 300 with allocation of 60% of the sample to the intervention PAC arm (n=178) and 40% of the sample (n=122) to UC to adjust for the adaptive design. Power estimates were calculated using data from the STRRIDE study19 in which a group receiving a low dose of moderate exercise, equivalent to the dose of moderate exercise advocated for the Enhanced Fitness study, reduced fasting insulin by 1.3 units while the control group experienced an increase in fasting insulin of 0.92 units with a pooled standard deviation of 3.9. With correction for multiple comparisons between adaptive strategies and a projected 12.5% attrition rate based on our previous experience, our sample size was 80% powered to detect a standardized difference of 0.39 in fasting insulin for a two-tailed test.

Analyses were performed under the intent-to-treat criteria. With three data points (baseline, 3-month, 12-month), and to accommodate missing values (due to dropout, lost to follow-up, death), mixed models were utilized.20 Data were analyzed according to good clinical practices.21 The baseline value of the particular outcome was entered as a covariate to adjust residual baseline differences between the groups at baseline. A series of contrasts was defined to assess group difference post baseline which assess PAC versus UC. Where necessary, data were log transformed for analysis. For the primary outcomes the statistical significance of both the Group and TimeXGroup interactions were assessed. The interpretation of the level of significance was adjusted to reflect three outcomes for the glycemic indicators, by a Bonferronicorrection.22

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study sample are presented in TABLE 1. The average age of the sample was 67 year with a range of 60 to 89. In contrast to most behavioral interventions which tend to enroll individuals with higher educational status, 46% of our sample had only a high school degree or less. Physical function (mean 72) was comparable to the general population for males ages 65 and over.23 Participants had normal usual walking speeds for their age but were at the 10th percentile in norms for six-minute walk distance indicating poor aerobic capacity for their age.24,25

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants

| Intervention | Usual Care | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Characteristics | (n= 180) | (n=122) |

| Age, mean (± SD), range | 67.1 (6.3) 60–89 | 67.7 (6.2) 60–80 |

| 75 and above, No.% | 27 (15.0) | 24 (19.7) |

| White race, No.% | 129 (71.7) | 83 (68.0) |

| Male sex, No.% | 173 (96.1) | 119 (97.5) |

| Some college education or trade school, No.% | 107 (59.4) | 65 (53.3) |

| Number of comorbidities, mean (± SD) | 4.2 (2.4) | 3.9 (2.4) |

| Number of symptoms, mean (± SD) | 2.3 (1.7) | 2.0 (1.6) |

| Gait speed, mean m/sec (± SD) | 1.24 (0.3) | 1.25 (0.3) |

Of 302 patients randomized, 262 (86.8%) completed a 12-month follow-up visit which was what had been projected (87.5%). Reasons for withdrawal or attrition are listed in Figure 1. Sensitivity analyses between dropouts and those who completed the 12-month assessment revealed no baseline differences between groups for age, race, number of symptoms, general health and physical function. Body mass index was slightly higher among drop outs; 32.2 versus 31.0, p=0.04.

Change in Glycemic Indicators

There were no significant differences between the PAC or UC groups over time for any of the glycemic indicators. Both groups had small declines over time of approximately 6% in fasting blood glucose, p< 0.001, while other glycemic indicators remained relatively stable. The modest declines in fasting glucose were not sufficient to affect the change in HOMA-IR scores due to fluctuations in insulin over time. HbA1c remained stable throughout the year. Four percent of the sample, 7 in PAC and 4 in UC were diagnosed with diabetes during the one-year intervention period. Post-hoc analyses examining dose-response and potential thresholds suggestive of improved glycemic indicators did not yield significant findings.

Change in Physical Activity

Walking and other endurance physical activity increased significantly over time for the PAC group from an average 73 minutes per week at baseline to an average 133 minutes per week at 12-months (+82%) in comparison to the Usual Care group whose endurance physical activity remained constant from 115 minutes per week at baseline to 112 minutes per week at 12- months, p = 0.0002 for between group difference. The prevalence of individuals meeting the goal of 150 minutes of endurance exercise increased in the PAC group over time from 16% to 42% in contrast to the UC groups whose prevalence of individuals meeting the 150 minute per week marker was stable over time (31%), OR = 1.65 (95%CI 1.08, 2.53). Both groups increased strength training activities over time with no between group differences noted. Validation for self-reported activity was performed in two ways. A subset of study participants wore ankle step count activity monitors for one-week following each assessment point; a modest correlation, p=0.11 (n=39), between mean number of step counts per day and mean moderate minutes of endurance activities from the CHAMPS was observed at the 3-month assessment point only. Within the PAC arm, individuals were asked to record pedometer counts as part of their self-monitoring of physical activity and were encouraged to mail these to the investigative team. Among respondents, individuals averaged 5241 (n=90), 5585 (n=76), and 5643 (n=48) respectively for the baseline, three and 12-month assessments which mirrors the self-reported changes in minutes of endurance activity. Seventy-two percent of the total PAC group stated that receiving the pedometer motivated them to walk quite a bit or very much.

Change in Health Related Quality of Life and MOVE!®. Program Outcomes

Self-reports of health-related quality of life and physical function were stable throughout the intervention period. There were no changes over time or between groups for any of the subscales of the SF-36.

Only 15% of the randomized sample enrolled in MOVE!®.. On average, MOVE!® enrollees attended six interactive classroom sessions. Weight loss was higher among individuals choosing to engage in MOVE!® activities (−1.55 kg) than among those who did not (−0.89 kg). There were no other differences among MOVE!® participants for glycemic or PA outcomes.

Adverse events

Changes in health status were identified at each telephone contact during the follow-up survey, the telephone counseling, or by self-report. A total of 691 events were reported, reviewed and classified as either serious or non-serious. Non-serious events (n=650) included aches and pains, sore muscles, muscle cramps, headaches, colds and flu, minor injuries or cuts. Of these non-serious events, 36 were attributed to increased physical activity: pain related to pre-existing joint/back pain exasperated by exercise (n=20), falls that caused aminor injury (n=5), sore or pulled muscle (n=4), heat exhaustion (n=3), knee injury (n=1), finger injury (n=1), injury to head by exercise equipment (n=1), and developed blisters while walking (n=1). The remaining 41 health changes were classified as serious i.e. life threatening or resulting in a hospitalization. Two of these, both in PAC group, were attributed to the increased physical activity. One person experience radiating shoulder pain while walking on a treadmill which resulted in a hospitalization and one person fell from a treadmill which resulted in a broken femur. Two events were considered possibly attributable to increased physical activity. One person developed a TIA with symptoms of right sided numbness which resulted in a hospitalization and one person experienced shortness of breath and subsequently diagnosed with amyocardial infarction. The remaining 37 health changes/illnesses, though serious, were not related to physical activity.

DISCUSSION

The Enhanced Fitness study included a theory-based physical activity counseling intervention with components known to increase physical activity. While substantial increases in physical activity were reported, there were no notable improvements in the primary endpoints pertaining to glycemic control. Although participants in the PAC arm of the study reported gradual and significant gains in physical activity over the 12-month intervention period, they largely did not attain the recommended therapeutic dose of 150 minutes of moderate physical activity per week necessary to impact insulin resistance.

These results are analogous to a clinic-based health lifestyle intervention provided to overweight patients with diabetes in which patients reported substantial gains in physical activity (+78%), modest weight loss with no change in diabetic control.26,27 A recent meta-analysis comparing structured exercise versus telephone advice concluded that telephone advice for physical activity alone was insufficient to achieve significant improvements in HbA1c in type 2 diabetic patients while structured exercise or telephone advice for both physical activity and diet were.28 Another meta-analysis focused on lifestyle interventions aimed at reducing diabetic risk in routine clinical practice.29 Results reported modest reductions in weight and waist circumferences with no clear effect on biochemical or clinical parameters. The authors concluded that given the positive changes observed and the apparent successful feasibility of integrating lifestyle intervention without excessive cost into the system, it seemed worthy to continue supporting these efforts along with rigorous evaluations in these settings.29

The magnitude of change in physical activity observed among individuals in the PAC group of the current study is quite meaningful from a public health perspective in that the participants were largely sedentary at baseline and made continuous strides in increasing physical activity throughout the counseling period. Reducing sedentary behaviors, independent of physical activity has known cardiovascular, metabolic, and functional benefits among older adults.30,31 Moreover, the PAC intervention was designed to be lower in cost and more convenient to the patient, which increases its appeal to providers and patients alike.

This study was directed at outpatients receiving care in VA primary care clinics. This presents numerous challenges. As a whole, Veterans receiving care at the VA tend to have more chronic diseases, poorer health, lower income and higher levels of unemployment than individuals receiving health care in the private sector.32,33 Our health counselors noted, in comparison to our prior research on older Veterans which had been heavily dominated by World War II Veterans, a higher prevalence of depressive disorders and post traumatic disorder syndromes, as more Vietnam-era Veterans aged into geriatric care. As noted in the results, changes in physical activity were gradual from a baseline of 73 minutes per week for endurance activities to 124 minutes per week at 3 months and 133 minutes per week at 12 months; a nearly two-fold increment. One can only speculate whether a longer intervention period would have yielded continued gains in physical activity with a concomitant improvement in insulin resistance. Most of the studies that have observed meaningful results in reducing diabetes incidence and other glycemic indicators have been of longer duration.3,34

Although the results of this study were largely stable regarding the primary outcome, there are numerous positives. Most health outcomes did not worsen throughout the year and several showed trends in positive directions: i.e., fasting glucose, weight, and low density lipoproteins declined and high density lipoproteins increased. We additionally were constrained by budget which did not allow us to conduct oral glucose tolerance tests which might have been more sensitive to change. Six minute walk distance improved modestly from baseline to 12- months; the raw mean change observed in the PAC group was not statistically significant but is considered a small meaningful change relative to clinical outcomes using anchor-based methods of responsiveness to change analysis.35 Integration with the primary care providers was successful; 74% of individuals in the PAC group reported that their provider encouraged physical activity during a clinic visit and 84% believed that the study gave them necessary tools to lower their risk of developing disease. Using a combined mailing and telephone counseling approach made the program more accessible given that 50% of the sample lived greater than 25 miles from their VA clinic. An inherent challenge of integrating research-based methods into routine clinical care has to do with maximizing uptake of these programs. The entire sample in our study (PAC and UC) were given a consult into the VA MOVE!® program yet only 15 % of the sample chose to participate. How to get the other 85% of at-risk people involved, for these voluntary programs remains unknown. Although not officially documented, many participants acknowledged that they were not physically active and were overweight but did not perceive themselves as being at risk for diabetes. Another smaller proportion of individuals expressed concern that if they engaged in health promoting activities they might be at-risk for losing their disability (monetary) benefits. While 87% of participants in the PAC arm felt that they had gained tools to help them reduce their risk of diabetes, only 24% of individuals in the PAC arm expressed a willingness to pay for an individual physical activity counseling session. All of these issues are important as we continue to strive to promote adherence to a healthier lifestyle.

There are obvious limitations to this study. Physical activity was determined by self-report. A very small subset of the study sample wore step count monitors as validation of self-reported activity. As noted in the results, we found a modest correlation between self-report and step counts at three but not 12-months. As more technology to assess physical activity becomes readily available and less costly, future studies of this nature can include more thorough assessment of physical activity. We regret that we were unable to implement the most attractive feature of our original design which included a group therapy for non-adherent; this was possibly a result of our lack of precise physical activity measurement. Another limitation was that despite randomization, there were substantial differences in physical activity at baseline between the two arms. This may have affected some of our between group outcomes.

In conclusion, this study highlights the challenges faced in promoting physical activity and lifestyle changes within primary care practice. The fact that positive change was observed in the UC groups attests to the efforts put forth by the VA in managing their at-risk patients. Unfortunately, the low levels of physical activity observed in the patients also highlight the failure of our system to fully integrate physical activity promotion into these efforts. Although we have successfully implemented a promising intervention, low physical activity remains pervasive in this population. Additional efforts are needed to maintain long-term improvement and maintenance of these efforts. Future research will likely include more emphasis on combined lifestyle changes (physical activity and diet) and seek to explore ways of increasing long-term uptake in these at-risk populations.

Table 2.

Group Means and Differences Between Group Means for all Outcomes

| Outcomes | Intervention | Usual Care | P Value† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3Month | 12Month | Baseline | 3Month | 12Month | ||

| Primary | |||||||

| Insulin (uIU/ml) | 10.26 ± 6.09 | 10.04 ± 7.21 | 11.4 ± 6.84 | 10.39 ± 8.58 | 10.45 ± 7.82 | 10.28 ± 5.59 | .43‡ |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 110.51 ± 6.95 | 106.96 ± 9.59 | 104.35 ± 9.62 | 110.60 ± 7.10 | 107.63 ± 9.62 | 104.38 ± 11.97 | .91‡ |

| HOMA_IR | 1.41 ± 0.83 | 1.35 ± 0.82 | 1.49 ± 0.94 | 1.45 ± 1.20 | 1.42 ± 1.14 | 1.37 ± 0.86 | .58 |

| Secondary Metabolic | |||||||

| Hemoglobin A1c | 5.89 ± 0.41 | 5.93 ± 0.42 | 5.90 ± 0.44 | 5.91 ± 0.41 | 5.91 ± 0.43 | 5.93 ± 0.36 | .08 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 171.1 ± 33.8 | 167.5 ±31.5 | 167.9 ±32.7 | 179.0 ±36.7 | 176.5 ±34.1 | 171.6 ±33.9 | .68 |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 39.2 ±12.6 | 40.0 ±11.8 | 45.3 ±13.2 | 38.5 ±11.1 | 40.0 ±11.7 | 44.8 ±13.3 | .87‡ |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 105.7 ±30.5 | 103.1 ±28.7 | 98.1 ±30.0 | 113.7 ±31.3 | 111.4 ±31.1 | 102.2 ±31.5 | .84‡ |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 131.8 ±69.5 | 121.1 ±64.3 | 131.4 ±74.0 | 144.6 ±139.7 | 133.3 ±114.9 | 123.2 ±64.2 | .25 |

| Physical Activity | |||||||

| PA Endurance (min/wk) | 73.39 ± 119.81 | 124.30 ± 127.15 | 133.60 ± 136.47 | 115..29 ± 183.66 | 92.87 ±115.01 | 112.62 ± 135.45 | <.001 |

| PA Strength (min/wk) | 19.19 ± 74.97 | 20.92 ± 33.46 | 28.44 ± 57.62 | 25.11 ± 75.68 | 27.42 ± 68.69 | 40.15 ± 93.35 | .11 |

| Health Related QOL | |||||||

| General Health (range 0–100) | 61.39 ± 39.40 | 59.84 ± 42.59 | 58.12 ± 42.29 | 65.78 ± 39.52 | 66.37 ± 42.75 | 61.68 ± 41.82 | .92 |

| Physical Function (range 0–100) | 62.94 ± 20.97 | 63.97 ± 21.30 | 62.52 ± 21.79 | 66.88 ± 20.60 | 67.08 ± 19.86 | 66.24 ± 20.91 | .09 |

| 6-minute walk, (m) | 495.7 ± 119.9 | 516.5 ± 128.2 | 518.3 ± 127.4 | 500.9 ± 109.3 | 526.4 ± 113.9 | 517.2 ± 129.1 | .81 |

| Anthrometric | |||||||

| BMI | 31.35 ± 3.75 | 30.90 ± 3.73 | 30.74 ± 3.88 | 30.97 ± 3.45 | 30.89 ± 3.60 | 30.64 ± 3.62 | .31 |

| Weight (kg) | 94.08 ± 13.03 | 92.89 ± 12.69 | 92.60 ± 13.62 | 94.51 ± 12.81 | 94.28 ± 13.10 | 93.67 ± 13.13 | .34 |

| Waist Circumference (cm) | 104.22 ± 9.04 | 104.23 ± 8.53 | 103.92 ± 10.02 | 103.98 ± 8.51 | 104.03 ± 8.10 | 104.43 ± 11.73 | .68 |

P values are for the group X time interactions indicating between group differences

P<0.001 for time effect with no between group differences

Acknowledgments

Funding sources:

Training grant received from National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (1KM1CA156687 to MJP).

This study was funded by a VA Health Services Research and Development grant IIR-06-252-3 (Morey PI) and National Institute on Aging Grant AG028716. Intervention materials have been developed with prior support from VA Rehabilitation Research Service grants (RRD-E2756R, RRD-E3386R) and National Cancer Institute grant CA106919. Miriam Morey is supported by the Durham VA Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center and Hayden Bosworth is supported by a Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Career Scientist Award (RCS 08-027). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

The authors wish to acknowledge and thank Teresa Howard, CarolaEkelund, Jennifer Chapman, Beverly McCraw, JoiDeberry, and Irv Eisen for their contributions in the successful execution of this clinical trial. We also wish to thank the following primary and geriatric care providers for their support of this project: Lori Bastian, MD, Marie Carlson, MD, James Galkowski, PA-C, Kenneth Goldberg, MD, MahlonGrimsley, PA-C, Wendy Henderson, MD, Jane Kim, MD, William Knaack, MD, Susan Lander, ANP, Andrea McChesney, RN, FNP, Douglas McCrory, MD, Carol McMorrow, PA-C, Eugene Oddone, MD, Benjamin Powers, MD, Susan Rakley, MD, William F Smith, PA-C, Amy Rosentahl, MD, David Simel, MD, Jeannette Stein, MD, James Tulsky, MD, John Williams, MD, Ernest Daniels, MD, Susan D Denny, MD, Jerome A Ecker, MD, Kathleen R Howard, MD, Robert Falge, MD, and, Suzanne Hixson GNP. We wish to thank and acknowledge the Durham VA Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center for its continued support of our research. And we wish to thank the VA Research program for providing infrastructure support for this project. And finally, we are grateful for the participating Veterans and their families for their gracious contribution to this research. The views express by the authors do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00594399.

Sponsors Role: The sponsors had no role in the project beyond funding.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: MCM, CFP, DEE, WSY, JBG, MJP, PAC, HBB, and MPP participated in the development of the study design and concept. MCM and MPP supervised the primary oversight of the trial. MCM, CFP, RS and MJP analyzed the data. MPP, MJP, and MCM, assisted with the acquisition of study participants. HL and GAT assisted with matters pertaining to laboratory assays. All authors participated in the interpretation of the data and in the preparation and review of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest: This study was funded by a VA Health Services Research and Development grant IIR-06-252-3 (Morey PI) and National Institute on Aging grant AG028716. Intervention materials have been developed with prior support from VA Rehabilitation Research Service grants (RRD-E2756R, RRD-E3386R) and National Cancer Institute grant CA106919. Miriam Morey is supported by the Durham VA Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center and Hayden Bosworth is supported by a Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Career Scientist Award (RCS 08-027). The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control. [Accessed December 7, 2011];National diabetes fact sheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States. 2011 Available at: www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/factsheet11.htm.

- 2.Crandall J, Schade D, Ma Y, et al. The influence of age on the effects of lifestyle modification and metformin in prevention of diabetes. J Gerontol: Med Sci Oct. 2006;61:1075–1081. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.10.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laaksonen DE, Lindstrom J, Lakka TA, et al. Physical activity in the prevention of type 2 diabetes: The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Diabetes. 2005;54:158–165. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morey MC, Peterson MJ, Pieper CF, et al. The Veterans Learning to Improve Fitness and Function in Elders study: A randomized trial of primary care-based physical activity counseling for older men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1166–1174. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morey MC, Snyder DC, Sloane R, et al. Effects of home-based diet and exercise on functional outcomes among older, overweight long-term cancer survivors: RENEW: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:1883–1891. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lavori PW, Dawson R. Dynamic treatment regimes: practical design considerations. Clin Trials. 2004;1:9–20. doi: 10.1191/1740774s04cn002oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall KS, Pieper CF, Edelman DE, et al. Lessons learned when innovations go awry: A baseline description of a behavioral trial--The Enhancing Fitness in Older Overweight Veterans with Impaired Fasting Glucose study. Translational Behav Med. 2011;1:573–587. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0075-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson ME, Rejeski WJ, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity and public health in older adults: Recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007;116:1094–1105. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psycho Rev. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sigal RJ, Kenny GP, Wasserman DH, et al. Physical activity/exercise and type 2 diabetes. Diab Care. 2004;27:2518–2539. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dept of Health and Human Services. 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Dept of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morey MC, Peterson MJ, Pieper CF, et al. The Veterans Learning to Improve Fitness and Function in Elders Study: A randomized trial of primary care based physical activity counseling for older men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1166–1174. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stewart AL, Mills KM, King AC, et al. CHAMPS physical activity questionnaire for older adults: outcomes for interventions. Med Sci Sports Exer. 2001;33:1126–1141. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200107000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stewart AL, Verboncoeur CJ, McLellan BY, et al. Physical activity outcomes of CHAMPS II: A physical activity promotion program for older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56A:M465–M470. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.8.m465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware JE, Jr, Bayliss MS, Rogers WH, et al. Differences in 4-year health outcomes for elderly and poor, chronically ill patients treated in HMO and fee-for-service systems. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1996;276:1039–1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ware JE, Jr, Snow KK, Kosinski M, et al. SF-36® Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric Incorporated; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fillenbaum GG. Multidimensional Functional Assessment of Older Adults. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraus WE, Torgan CE, Duscha BD, et al. Studies of a targeted risk reduction intervention through defined exercise (STRRIDE) Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:1774–1784. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200110000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laird N, Ware J. Random effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982;38:963–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ICH E9 Expert Working Group. ICH harmonised tripartite guideline - statistical principles for clinical trials. Stat Med. 1999;18:1905–1942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleiss J. The Design and Analysis of Clinical Experiments. New York: Wiley; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ware JE., Jr SF-36 health survey update. Spine. 2000;25:3130–3139. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bohannon RW, Andrews AW, Thomas MW. Walking speed: reference values and correlates for older adults. J Ortho Sports Phys Ther. 1996;24:86–90. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1996.24.2.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rikli RE, Jones CJ. Functional fitness normative scores for community-residing older adults, ages 60–94. J Aging Phys Act. 1999;7:162–181. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christian JG, Bessesen DH, Byers TE, et al. Clinic-based support to help overweight patients with type 2 diabetes increase physical activity and lose weight. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:141–146. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirk A, Barnett J, Leese G, Mutrie N. A randomized trial investigating the 12-month changes in physical activity and health outcomes following a physical activity consultation delivered by a person or in written form in Type2 diabetes: Time2Act. Diabetic Med. 2009;26:293–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Umpierre D, Ribeiro PA, Kramer CK, et al. Physical activity advice only or structured exercise training and association with HbA1c levels in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305:1790–1799. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cardona-Morrell M, Rychetnik L, Morrell S, et al. Reduction of diabetes risk in routine clinical practice: Are physical activity and nutrition interventions feasible and are the outcomes from reference trials replicable? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:653. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bankoski A, Harris TB, McClain JJ, et al. Sedentary activity associated with metabolic syndrome independent of physical activity. Diab Care 2011. 2011;34:497–503. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elosua R, Bartali B, Ordovas JM, et al. Association between physical activity, physical performance, and inflammatory biomarkers in an elderly population: The InCHIANTI study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:760–767. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.6.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk J, et al. Are patients at Veterans Affairs Medical Center sicker?: A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3252–3257. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reiber GE, Koepsell TD, Maynard C, et al. Diabetes in nonveterans, veterans, and veterans receiving Department of Veterans Affairs health care. Diabetes Care. 2004;27 (Suppl 2):B3–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.suppl_2.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ilanne-Parikka P, Laaksonen DE, Eriksson JG, et al. Leisure-time physical activity and the metabolic syndrome in the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Diabetes Care 2010. 2010;33:1610–1617. doi: 10.2337/dc09-2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perera S, Mody SH, Woodman RC, et al. Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:743–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]