Abstract

The pregnant sheep has provided seminal insights into reproduction related to animal and human development (ovarian function, fertility, implantation, fetal growth, parturition and lactation). Fetal sheep physiology has been extensively studied since 1950, contributing significantly to the basis for our understanding of many aspects of fetal development and behaviour that remain in use in clinical practice today. Understanding mechanisms requires the combination of systems approaches uniquely available in fetal sheep with the power of genomic studies. Absence of the full range of sheep genomic resources has limited the full realization of the power of this model, impeding progress in emerging areas of pregnancy biology such as developmental programming. We have examined the expressed fetal sheep heart transcriptome using high-throughput sequencing technologies. In so doing we identified 36,737 novel transcripts and describe genes, gene variants and pathways relevant to fundamental developmental mechanisms. Genes with the highest expression levels and with novel exons in the fetal heart transcriptome are known to play central roles in muscle development. We show that high-throughput sequencing methods can generate extensive transcriptome information in the absence of an assembled and annotated genome for that species. The gene sequence data obtained provide a unique genomic resource for sheep specific genetic technology development and, combined with the polymorphism data, augment annotation and assembly of the sheep genome. In addition, identification and pathway analysis of novel fetal sheep heart transcriptome splice variants is a first step towards revealing mechanisms of genetic variation and gene environment interactions during fetal heart development.

Key points

The sheep is a valuable model for biomedical research, including the study of developmental programming mechanisms that are critical to better understand gene–environment interactions responsible for each individual's phenotype and predisposition to chronic diseases.

The lack of genetic and genomic resources for the sheep has limited the power of this model, impeding progress in emerging areas of pregnancy biology and other fields of biomedical research.

In this study, we examined the expressed fetal sheep heart transcriptome using high-throughput sequencing technologies.

We identified 36,737 novel transcripts and describe genes, gene variants and pathways relevant to fundamental developmental mechanisms.

The data presented in this study provide a foundation of genetic information on the repertoire of genes expressed in the fetal heart transcriptome, which will augment annotation and assembly of the sheep genome.

Introduction

Animal models are essential to understanding molecular and systems physiology and gene–environment interactions that determine phenotype, life-course function and disease mechanisms. The sheep is widely acknowledged as a major animal model with dual-purpose benefit for agricultural and biomedical research (Ireland et al. 2008), extensively studied to determine fundamental reproductive processes: ovarian function (Steckler et al. 2007; Doerr et al. 2008), implantation and trophoblast physiology (Chakrabarty & Roberts, 2007), neuroendocrinology (Knutson & Wood, 2010), parturition (McDonald & Nathanielsz, 1991; Nathanielsz, 1998) and lactation (Meyer et al. 2011). In recent years for practical and scientific reasons described below the sheep has been a major model investigated to determine developmental programming mechanisms. Developmental programming can be defined as responses to challenges during critical pre-conceptual, peri-conceptual and fetal and neonatal time windows that alter developmental trajectory with persistent effects on phenotype. Studies of developmental programming mechanisms are critical to a better understanding of gene–environment interactions responsible for each individual's life-time phenotype and predisposition to chronic diseases (Armitage et al. 2004; McMillen & Robinson, 2005; Poston 2001).

Several species have been studied as models to determine mechanisms of developmental programming (Armitage et al. 2004a). The pregnant sheep and her fetus provide a unique opportunity to conduct chronic fetal studies in a species that, like humans, typically produces one or two offspring. In addition the developing lamb follows a precocial developmental trajectory characterized by many similar fetal development milestones to humans. By contrast polytocous, altricial rodents follow a different developmental pattern in which many stages that are in utero in precocial species occur post-natally when key factors interacting with the genome, metabolites, hormones and even  have undergone delivery associated changes (Rueda-Clausen et al. 2011). Since Barcroft's early studies on fetal physiology in the mid 1900s (Barcroft & Barron, 1936), this species has been the most extensively investigated in relation to fetal development of systems physiology, particularly in relation to developmental programming (Armitage et al. 2004; McMillen & Robinson, 2005). Examples can be taken from among, but not exclusively, the following areas: pancreatic islet function and predisposition to diabetes (Ford et al. 2007), cardiovascular development (Giussani et al. 1994) and altered pre-load and after load (O’Tierney et al. 2010); lung development and morbidity and mortality accompanying prematurity (Liggins, 1969); development of respiratory and sleep state behaviours in utero (Moore et al. 1989; Watson et al. 2002); and neuroendocrine development (Giussani et al. 2011) and initiation of parturition (McDonald & Nathanielsz, 1991). However, sheep genetic and genomic resources are still scarce, requiring investigators to sequence single target genes of interest. In order to develop genomic resources for the sheep and to provide data on an organ essential to fetal development and survival, we sequenced the sheep fetal heart transcriptome, taking advantage of high-throughput sequencing technologies to annotate transcribed genomic regions. In doing so, next-generation sequencing tools have allowed identification of genes, novel single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and novel splice variants in the absence of species-specific reagents and an assembled genome.

have undergone delivery associated changes (Rueda-Clausen et al. 2011). Since Barcroft's early studies on fetal physiology in the mid 1900s (Barcroft & Barron, 1936), this species has been the most extensively investigated in relation to fetal development of systems physiology, particularly in relation to developmental programming (Armitage et al. 2004; McMillen & Robinson, 2005). Examples can be taken from among, but not exclusively, the following areas: pancreatic islet function and predisposition to diabetes (Ford et al. 2007), cardiovascular development (Giussani et al. 1994) and altered pre-load and after load (O’Tierney et al. 2010); lung development and morbidity and mortality accompanying prematurity (Liggins, 1969); development of respiratory and sleep state behaviours in utero (Moore et al. 1989; Watson et al. 2002); and neuroendocrine development (Giussani et al. 2011) and initiation of parturition (McDonald & Nathanielsz, 1991). However, sheep genetic and genomic resources are still scarce, requiring investigators to sequence single target genes of interest. In order to develop genomic resources for the sheep and to provide data on an organ essential to fetal development and survival, we sequenced the sheep fetal heart transcriptome, taking advantage of high-throughput sequencing technologies to annotate transcribed genomic regions. In doing so, next-generation sequencing tools have allowed identification of genes, novel single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and novel splice variants in the absence of species-specific reagents and an assembled genome.

The first extensive linkage sheep genome map, contained 246 microsatellite markers and covered 2070 cM (Crawford et al. 1995), giving an average marker density of 8.4 cM. The current sheep genome linkage map contains 1374 markers, spans 3630 cM and includes microsatellite, SNP and cytogenetic markers (Burkin et al. 1997; Iannuzzi et al. 1999). These markers have been used with comparative genomic methods to construct a virtual sheep genome using the human genome as a reference to order the 84,624 sequenced sheep genomic DNA BAC clones into 1172 scaffolds (Dalrymple et al. 2007). However, the current draft assembly of the sheep genome sequence, which is ordered by sheep chromosomes, consists of 1358 scaffolds and cannot be used as a reference genome for sequence assembly and annotation with current analysis tools (Hosseini et al. 2010).

Here, we used the latest assembly of the annotated cow genome (Bos taurus; Btau 4.0, October 2007, Baylor College of Medicine-Human Genome Sequencing centre, (The Bovine Genome Sequencing and Analysis Consortium, 2009) as a reference because of the close evolutionary distance between sheep and cow, and since it is assembled with defined chromosomal locations. Because the cow assembly is not as extensively annotated as the human genome, we also used the human genome as a second pass for analysis of our data to identify splice variants and genes that may not yet be annotated in the cow genome sequence. Although we used reference genomes from other species, our sheep sequence data composed of 76 bp paired-end reads adds much greater confidence in sequence assembly and alignment compared with earlier high-throughput sequencing protocols, which generated 36 bp single-end reads. The longer reads and the sequencing of both ends of each cDNA fragment (paired-ends) provide additional data for alignment and additional data for identification of splice variants by using reads whose ends are anchored in different exons to define splice sites without relying on prior annotations.

We used high-throughput sequencing to generate extensive transcriptome information in the absence of a well-annotated genome in this important experimental species and thereby provide a resource for development of genetic tools that, combined with the polymorphism data, will be useful for further annotation of the sheep genome. The information obtained provides a foundation of genetic information on the repertoire of genes expressed in the fetal heart transcriptome that will also be of use in other situations such as the influence of gene–environment interactions that predispose to chronic conditions such as cardiovascular (Louey et al. 2007) and endocrine dysfunction (Giussani et al. 2011), diabetes (Sloboda et al. 2005) and obesity (Wang et al. 2010) commonly modelled in this species.

Methods

Care and use of animals

All animal procedures were approved by the University of Wyoming Animal Care and Use Committee and previously described in detail (Ford et al. 2009). Only ewes carrying twin fetuses were studied. Animal husbandry and breeding have been described in detail previously (Zhu et al. 2008). Fetal left ventricular tissue was obtained at necropsy from 14 male fetuses at 135 days gestation. Ewes were sedated with ketamine (10 mg (kg body weight)−1) and maintained under isoflurane inhalation anaesthesia (2.5%). Fetuses and ewes were killed by exsanguination while still under general anaesthesia and the gravid uterus quickly removed. Fetal weight and sex were determined, and the fetal heart was quickly removed and weighed. The left ventricular free wall was dissected free, weighed, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C until utilized.

RNA extractions

Trizol Reagent was used to isolate total RNA from tissue according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, tissues were homogenized in 1 ml of Trizol Reagent per 50–100 mg of tissue using a power homogenizer (Power Gen). Homogenized samples were incubated for 5 min at 25°C to permit complete dissociation of nucleoprotein complexes. Chloroform (0.2 ml per 1 ml of Trizol Reagent) was added to each sample, shaken vigorously for 15 s, and incubated at 25°C for 3 min; samples were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4°C and the aqueous phase transferred to a fresh tube. RNA was precipitated in 0.5 ml of isopropyl alcohol per 1 ml of Trizol Reagent and incubated at 25°C for 10 min followed by centrifugation at 12,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was decanted and the pellet washed with 75% ethanol, adding at least 1 ml of 75% ethanol per 1 ml of Trizol Reagent. After air-drying, the RNA pellet was dissolved in DEPC-treated ddH2O and quantified spectrophotometrically. RNA was separated into single-use portions and stored at –140°C.

Sequencing of the fetal heart transcriptome

cDNA libraries were generated using the Illumina mRNA-Seq Sample Prep Kit (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA according to manufacturer's instructions. Clusters were generated for each library using the Illumina Paired-End Cluster Generation Kit v4 and Cluster Station, and the samples were pair-end sequenced for 76 bp per end using the Illumina v4 Sequencing Kit and GAIIx Sequencer. FASTQ files from the Illumina GAIIx sequencing runs were uploaded to GeneSifter (Geospiza Inc., Seattle, WA, USA) for sequence assembly and analysis. Sequence assembly was performed in two steps with the sequencing reads first assembled using the bovine genome with bovine RefSeq genes (October 2007 Baylor 4.0/bosTau4) build as a reference. Because the sheep genome sequence is not yet assembled as chromosomal units, it is not possible to use this as a reference with current sequence assembly and annotation tools (e.g. CASAVA; Hosseini et al. 2010).

Sequence read assembly and annotation

We aligned sequence reads using an analysis pipeline of Bowtie, TopHat, Cufflinks, (Langmead et al. 2009; Trapnell et al. 2009; Roberts et al. 2011), SAMtools (Li et al. 2009) and the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) (McKenna et al. 2010). Paired reads for each sample were aligned to bosTau4 with TopHat v 1.2.0, dependent upon Bowtie v 0.12.7 for read mapping, to generate a set of putative splice junction sites. We selected TopHat options that allowed for up to six mismatches per read with one in the anchor region, enabled indel reporting, and utilized a coverage search algorithm for greater sensitivity. Reads were then mapped against the TopHat database of splice junctions to produce an alignment suitable for transcript assembly and variant detection.

GATK analysis was performed on TopHat alignments consisting of PCR duplicate removal, indel realignment, and base quality score recalibration followed by SNP discovery and genotyping with exome-specific filtering (DePristo et al. 2011). Variant call output from the GATK UnifiedGenotyper was used to generate a consensus sheep genomic sequence with the cow genome as a guide. SNPs from this analysis include polymorphisms between the bovine reference genome and the sheep fetal heart sequences. All confident bases were emitted and filtered on base quality and read depth. Nucleotides with a Phred-like base quality score greater than or equal to 17 and read depth greater than or equal to 4 were reported with an upper-case designation. Lower-case bases were used to indicate nucleotides with a quality score less than 17 and/or read depth less than 4. SNP discovery was then repeated over the consensus sheep fetal heart sequence. These SNPs are polymorphisms among the 14 fetal sheep heart samples (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/snp_viewBatch.cgi?sbid=1055291).

The Cufflinks (University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA) v 1.0.3 Reference Annotation Based Transcript (RABT) assembly method was used to construct, identify, and estimate expression of both known cow and novel transcripts from TopHat alignments with multi-read correction and upper quartile normalization options, which were enabled to increase accuracy and sensitivity respectively. Differences in splicing, coding sequence output, and promoter usage among the 14 samples were identified with Cuffdiff (Trapnell et al. 2010). Assembled transcript sequences were generated with the gffread utility from the resulting sheep consensus sequence. Transcripts were annotated based on alignment of bovine genes and noncoding RNAs (http://cufflinks.cbcb.umd.edu).

Annotation of transcripts that did not align with annotated bovine genes

Novel transcript sequences from the RABT assembly were annotated based on their genomic coordinates within the bovine genome. The Table Browser in the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) Genome Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu) was used to create a custom track of the RABT assembly data. Galaxy (http://g2.bx.psu.edu) was then used to join this custom track with the bovine gene track (October 2007 Baylor 4.0/bosTau4) based on genomic interval overlap, using 1 bp as the minimum required overlap between the two gene tracks. Novel transcript sequences from the RABT assembly that did not align with the bosTau4 gene track were then mapped to the human genome (February 2009 GRCh3/hg19). The genomic coordinates (chromosome, chromosome start and chromosome end) for each of the novel transcripts were translated from the bovine genome (bosTau4) to the human genome (hg19) using the LiftOver utility in the Genome Browser. The translated coordinates were then joined with the human gene track (February 2009 GRCh3/hg19) based on genomic interval overlap, using 1 bp as the minimum required overlap between the two gene tracks.

Comparison to GenBank sheep genes

We used the UCSC BLAT alignment tool (Kent, 2002) to compare the fetal sheep heart RNA Seq cDNA sequences with Ovis aries NCBI RNA reference sequences (RefSeq) collection (Pruitt et al. 2007).

Pathway analysis

Gene expression data were overlaid onto Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathways (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) (Kanehisa et al. 2004) and Gene Ontologies (Ashburner et al. 2000) using GeneSifter software.

Results

Identification of genes in the fetal heart transcriptome

We processed 404,843,551 sheep fetal heart RNA reads and found 357,281,675 reads (88.25%) mapped to a unique location in the bovine genome (NCBI SRA submission: SRA030410.1). Assembly of the aligned reads provided sequence data for 9,407 genes with coverage equal to or greater than 1× (Supplemental Table 1). Included in this list are 396 hypothetical genes, hypothetical proteins and open reading frames annotated in the bovine genome (Supplemental Table 2). The range in expression is from 1- to 205,191-fold coverage. The percentage of ns within the sequence reads ranges from 0 to 98.61%. When aligned with the corresponding cow genes, it appeared that most of the ns within the sheep sequences represent exons or untranslated regions (UTRs) that are likely to differ between the two species. Chromosomal distribution of the annotated genes is shown in Table 1. We found 9245 genes based on common gene identifiers that were annotated in the bovine genome. The number of variants within a gene ranged from one splice variant to five splice variants, with an average of one splice variant per gene.

Table 1.

Number of annotated genes, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and splice variants per bovine chromosome

| Chr | Annotated transcripts | Sheep to cow genome novel transcipts | Total no. of genic genes | Total no. of splice variants | SNPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 350 | 738 | 466 | 622 | 2173 |

| 2 | 393 | 854 | 515 | 732 | 2421 |

| 3 | 603 | 1210 | 803 | 1010 | 2876 |

| 4 | 293 | 547 | 369 | 471 | 1591 |

| 5 | 509 | 1068 | 679 | 898 | 2458 |

| 6 | 247 | 492 | 330 | 409 | 1334 |

| 7 | 528 | 1151 | 725 | 954 | 2799 |

| 8 | 290 | 586 | 381 | 495 | 1509 |

| 9 | 185 | 347 | 253 | 279 | 1257 |

| 10 | 421 | 819 | 558 | 682 | 2457 |

| 11 | 448 | 899 | 597 | 750 | 2084 |

| 12 | 158 | 320 | 206 | 272 | 985 |

| 13 | 331 | 640 | 433 | 538 | 1892 |

| 14 | 188 | 395 | 253 | 330 | 1010 |

| 15 | 287 | 638 | 371 | 554 | 1516 |

| 16 | 265 | 524 | 342 | 447 | 1448 |

| 17 | 267 | 515 | 369 | 413 | 1422 |

| 18 | 505 | 1003 | 673 | 835 | 2814 |

| 19 | 569 | 1183 | 762 | 990 | 2669 |

| 20 | 144 | 248 | 183 | 209 | 762 |

| 21 | 202 | 387 | 279 | 310 | 1213 |

| 22 | 271 | 611 | 386 | 496 | 1342 |

| 23 | 286 | 696 | 380 | 602 | 1858 |

| 24 | 117 | 228 | 161 | 184 | 846 |

| 25 | 339 | 688 | 445 | 582 | 1369 |

| 26 | 151 | 377 | 201 | 327 | 1308 |

| 27 | 101 | 191 | 130 | 162 | 609 |

| 28 | 125 | 268 | 167 | 226 | 993 |

| 29 | 258 | 513 | 341 | 430 | 1045 |

| X | 218 | 485 | 308 | 395 | 920 |

| M | 0 | 1 | |||

| Unknown | 358 | ||||

| Total | 9049 | 18621 | 12066 | 15604 | 48981 |

SNPs indicate variants among the 14 sheep samples, and splice variants denote differences compared with annotated bovine genes. Total no of splice variants: defined as more than one transcript for a ‘genic’ gene.

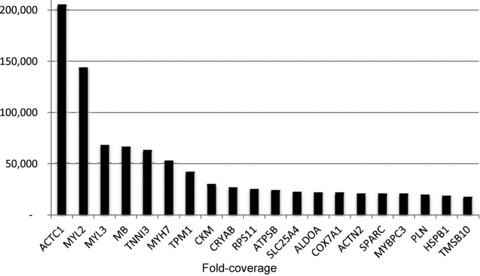

The top 20 annotated genes, ranked by abundance, include: actin α (cardiac muscle 1), myosin light chain 2 (regulatory, cardiac, slow), myosin light chain 3 (alkali; ventricular, skeletal, slow), myoglobin, troponin I type 3 (cardiac), myosin heavy chain 7 (cardiac muscle, β), tropomyosin 1 (α), creatine kinase (muscle), crystalline αB, ribosomal protein S11, ATP synthase (H+ transporting, mitochondrial F1 complex, β polypeptide), solute carrier family 25 member 4 (mitochondrial carrier; adenine nucleotide translocator), aldolase A (fructose-bisphosphate), cytochrome c oxidase subunit VIIa polypeptide 1 (muscle), actinin (α 2), osteonectin (secreted protein, acidic, cysteine-rich), myosin binding protein C (cardiac), phospholamban, heat shock 27 kDa protein 1 and thymosin β 10. Ten of the top 20 genes encode muscle-related proteins and range from 17,468- to 205,191-fold coverage (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Expression of the top 20 most highly expressed genes in sheep fetal heart.

The x-axis shows each Gene ID.

Comparison of GenBank sheep genes with fetal heart RNA Seq genes

GenBank contains 1708 gene records for sheep. After filtering out duplicates and partial cDNAs, there were 749 full-length sheep cDNA sequences. Comparison of fetal sheep heart cDNA sequences with GenBank sheep genome and cDNAs revealed 252 fetal sheep heart cDNAs that aligned with GenBank sheep cDNAs and seven fetal sheep heart cDNAs that aligned with the sheep genome and homologues of the gene from other species, but the NCBI sheep RefSeq cDNA is not included in the alignment (bold genes listed in Supplemental Table 3). Alignment showed 203 full-length cDNA sequences that were longer in the sheep fetal heart samples than the reported sheep GenBank RefSeq cDNA. The transcript length differences were typically due to the presence of an additional exon and/or additional 3′ untranslated region (UTR) nucleotides in the fetal sheep cDNA and bovine cDNA that were not included in the sheep RefSeq cDNA. These additional bases in the sheep fetal heart cDNAs aligned to the sheep genome sequence. Sequence identity for the aligned nucleotides ranged from 83.2 to 100% with 215 sequences 99% identical between the RNA Seq cDNAs and RefSeq cDNAs (Supplementary Table 3). No full-length cDNAs from our dataset aligned with the remaining 500 full-length sheep RefSeq cDNAs (data not shown). Consequently, 9172 of the genes sequenced in this study are novel.

Pathway analysis of genes expressed in the sheep fetal heart transcriptome

KEGG pathway analysis of the fetal heart transcriptome revealed 62 significant KEGG pathways containing quality fetal heart genes. Top ranking pathways included: ribosome, ubiquitin mediated proteolysis, lysosome, neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, RNA transport, oxidative phosphorylation, focal adhesion, regulation of actin cytoskeleton and cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction signalling pathways (Table 2). Analysis of expressed genes using GO biological processes showed 275 categories containing ≥4 genes and included: nitrogen compound metabolic processes, cellular nitrogen compound metabolic processes, cellular biosynthetic processes, nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolic processes, protein metabolic processes, gene expression, localization and macromolecule biosynthetic processes (Supplemental Table 4).

Table 2.

KEGG pathways for expressed genes

| KEGG pathway | Gene count |

|---|---|

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 35 |

| African trypanosomiasis | 18 |

| Allograft rejection | 15 |

| α-Linolenic acid metabolism | 5 |

| Alzheimer's disease | 104 |

| Amoebiasis | 45 |

| Arachidonic acid metabolism | 19 |

| Ascorbate and aldarate metabolism | 6 |

| Asthma | 11 |

| Autoimmune thyroid disease | 16 |

| Axon guidance | 53 |

| B cell receptor signalling pathway | 43 |

| Base excision repair | 23 |

| Bile secretion | 26 |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 40 |

| Citrate cycle (TCA cycle) | 23 |

| Complement and coagulation cascades | 31 |

| Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | 101 |

| Drug metabolism – cytochrome P450 | 23 |

| Drug metabolism – other enzymes | 11 |

| Ether lipid metabolism | 15 |

| Fat digestion and absorption | 16 |

| Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis | 54 |

| Focal adhesion | 92 |

| Glycolysis / Gluconeogenesis | 43 |

| Insulin signalling pathway | 70 |

| Intestinal immune network for IgA production | 22 |

| Jak-STAT signalling pathway | 51 |

| Linoleic acid metabolism | 3 |

| Lysosome | 80 |

| Maturity onset diabetes of the young | 5 |

| Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 | 20 |

| mRNA surveillance pathway | 45 |

| Neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction | 81 |

| Neurotrophin signalling pathway | 66 |

| Non-small cell lung cancer | 27 |

| Nucleotide excision repair | 35 |

| Olfactory transduction | 12 |

| Other types of O-glycan biosynthesis | 16 |

| Oxidative phosphorylation | 91 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 43 |

| Pancreatic secretion | 36 |

| Pathways in cancer | 149 |

| Phototransduction | 11 |

| Propanoate metabolism | 27 |

| Protein digestion and absorption | 23 |

| Protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum | 103 |

| Pyruvate metabolism | 30 |

| Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | 98 |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 41 |

| Retinol metabolism | 10 |

| Riboflavin metabolism | 3 |

| Ribosome | 76 |

| RNA degradation | 42 |

| RNA transport | 87 |

| Starch and sucrose metabolism | 14 |

| Steroid hormone biosynthesis | 9 |

| Taste transduction | 11 |

| Type I diabetes mellitus | 17 |

| Ubiquitin mediated proteolysis | 79 |

| Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation | 36 |

| Wnt signalling pathway | 68 |

KEGG pathway analysis of the top 100 expressed genes included the ribosome, oxidative phosphorylation, dilated cardiomyopathy, cardiac muscle contraction, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and focal adhesion pathways (Table 3). Analysis of the same genes in GO biological process categories clustered genes related to heart contraction, heart development and heart process (Supplemental Table 5).

Table 3.

KEGG Pathways for top 100 expressed genes

| KEGG Pathway | Genes |

|---|---|

| Ribosome | 27 |

| Huntington's disease | 15 |

| Oxidative phosphorylation | 15 |

| Parkinson's disease | 15 |

| Alzheimer's disease | 14 |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 10 |

| Cardiac muscle contraction | 9 |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) | 8 |

| Focal adhesion | 6 |

| Amoebiasis | 5 |

| Tight junction | 5 |

| Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) | 4 |

| Glycolysis / Gluconeogenesis | 4 |

| Adherens junction | 3 |

| Citrate cycle (TCA cycle) | 3 |

| Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism | 3 |

| Pyruvate metabolism | 3 |

| Viral myocarditis | 3 |

Identification of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the fetal heart transcriptome

Analysis of the 14 fetal heart samples revealed 2,868,135 SNPs compared with the bovine genome and 48,981 high confidence SNPs among the 14 fetal heart transcriptome samples. We found one or more polymorphisms in 2249 annotated genic regions (coding sequence and untranslated region) and identified 500 SNPs in coding regions of genes, 10,698 in introns, 240 in 3′ UTRs, 47 in 5′ UTRs and 37,453 in genomic regions of the cow genome. We also found 43 SNPs in non-coding RNAs. The number of polymorphisms per gene (coding sequence and untranslated region) ranged from 1 to 253, with an average of five SNPs per gene. Chromosome distribution of SNPs is shown in Table 1, distribution of SNPs by genic region is shown in Table 4 and a detailed list of all SNPs is available in dbSNP (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/snp_viewBatch.cgi?sbid=1055291). There are currently 4626 sheep SNPs in dbSNP; however, none of these SNPs are mapped to chromosomal locations. Consequently it is not possible at this time to determine if there are any SNPs common to our dataset and those in dbSNP.

Table 4.

Sheep fetal heart single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) by genic regions

| Region | SNPs |

|---|---|

| Coding Sequence | 500 |

| Untranslated Region | 287 |

| Intergenic | 37,453 |

| Intronic | 10,698 |

| Total | 48,938 |

Identification of insertion–deletion polymorphisms (InDel)

We identified 31,713 InDels comparing sheep cDNA sequences with the bovine reference sequence. The chromosomal distribution of the InDels is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

InDel polymorphisms between sheep and cow cDNA sequences

| CHR | Sheep to cow InDels |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1329 |

| 2 | 1537 |

| 3 | 2158 |

| 4 | 1031 |

| 5 | 1943 |

| 6 | 1019 |

| 7 | 1981 |

| 8 | 943 |

| 9 | 669 |

| 10 | 1478 |

| 11 | 1582 |

| 12 | 556 |

| 13 | 1191 |

| 14 | 682 |

| 15 | 949 |

| 16 | 895 |

| 17 | 959 |

| 18 | 1365 |

| 19 | 1903 |

| 20 | 463 |

| 21 | 728 |

| 22 | 946 |

| 23 | 988 |

| 24 | 489 |

| 25 | 818 |

| 26 | 699 |

| 27 | 444 |

| 28 | 571 |

| 29 | 649 |

| X | 748 |

Novel sheep splice variants compared with cow

Sheep transcripts that did not map to the cow genome based on cow RefSeq genes were annotated using their genomic coordinates within the bovine genome. Aligning the chromosomal position of each sheep sequence with the cow genome, we identified 18,621 novel transcripts ranging in expression from 1- to 295,047-fold coverage (Supplemental Table 6). Of the 18,621 novel transcripts identified, 18,491 are coding RNAs and 130 are non-coding RNAs. Chromosomal distribution of the annotated genes is shown in Table 1. We found 7384 genic genes based on common gene identifiers. The number of variants within a gene ranged from one splice variant to 56 splice variants, with an average of 2.5 splice variants per gene.

Novel sheep splice variants compared with human

Genomic coordinates of sheep transcript sequences that didn't align with the cow genome were translated from the bovine genome to the human genome for comparison of genomic intervals. Aligning the chromosomal position of each translated sheep sequence with the human genome, we identified 9899 novel transcripts ranging in expression from 1- to 4,701,570-fold coverage (Supplemental Table 7). Of the 9899 novel transcripts identified, 9098 are coding RNAs and 801 are non-coding RNAs. We found 3007 genic genes based on common gene identifiers. The number of variants within a gene ranged from one splice variant to 598 splice variants, with an average of 3.3 splice variants per gene.

Identification of non-coding RNAs

Although library preparation enriches for mRNAs, sequences for microRNAs (miRNAs) and other non-coding RNAs were included in our dataset. We identified 32 miRNAs (Griffiths-Jones, 2010) that uniquely mapped to the bovine genome. Twenty-six were novel in sheep, and six of the miRNAs are known to be expressed in heart and play roles in muscle contractility, cardiac hypertrophy or muscle specific transcriptional signalling (Hamosh et al. 2005). Expression ranged from 2- to 180-fold coverage. We also identified 18 non-coding RNAs (other than miRNAs). Two of these non-coding RNAs are known to be expressed in heart, two are imprinted with one expressed from the paternal allele and the other from the maternal allele, and five have unknown functions. None of these non-coding RNAs were previously identified in sheep. Expression ranged from 1- to 4716-fold coverage (Supplemental Table 8). We also identified numerous miRNAs and other non-coding RNAs from the RABT assembly. Ninety-seven miRNAs and 33 other non-coding RNAs were identified by comparing genomic intervals of novel sheep variants to the cow genome. Expression ranged from 1- to 4,094-fold coverage (Supplemental Table 9). Sixty-four miRNAs and 737 other non-coding RNAs were also identified by comparing genomic intervals of novel sheep variants to the human genome. Expression ranged from 1- to 312,261-fold coverage (Supplemental Table 10).

Discussion

Annotation of the sequence data using the cow genome as a reference revealed expression of 9407 genes in the fetal sheep heart transcriptome. By aligning the non-annotated, but unique, cDNAs to the cow genome and human genome sequences, we identified an additional 18,491 and 9098 novel coding transcripts, respectively, which were not annotated in cow or sheep. Comparison of these gene sequences with full-length sheep RefSeq genes showed 259 genes common to both datasets, indicating that 36,737 genes sequenced in this study are novel. Pathway analysis of the most highly expressed genes, which provides biological context for gene expression, showed pathways known to be relevant to cardiac development and function. Taken together, these results indicate that we have generated a high quality sequence data resource representative of the fetal sheep heart transcriptome.

The high-throughput, paired-end sequencing of 14 sheep fetal heart RNA samples in this study gave, on average, 482 reads per base in the transcriptome. The range in expression is from 1- to 205,191-fold coverage, which is consistent with previous transcriptome studies showing a 105 range in gene expression. From these data, we identified 36,737 genes that are novel to the sheep heart transcriptome.

Because the bovine genome is not yet as well annotated as the human genome, we performed a second analysis of the unmapped sheep to bovine reads using the well-annotated human genome as a reference. To ensure high confidence alignments of these reads, we used a more stringent quality filter than with the bovine genome alignment. The results from this second alignment revealed an additional 9098 genes in the sheep fetal LV that were not annotated in the bovine genome.

In addition to analysis of splice variants, we performed analysis of genetic variation in this dataset by identifying SNPs. We found 48,981 high confidence SNPs among the 14 samples. Because the sheep SNPs in dbSNP have not yet been mapped to the genome, it isn't yet possible to determine if these SNPs overlap with the SNPs identified in this study. However, if there were overlap with the entire dbSNP dataset, then we’ve identified at least 44,355 high quality, novel sheep SNPs. Analysis of SNP locations, which is based on gene annotations in the cow genome, shows 37,453 SNPs mapping to ‘genomic’ regions. Our annotation of cDNAs that did not align to annotated cow genes but do align to specific chromosomal regions containing genes suggests that many of these ‘genomic’ SNPs are contained in genes not yet annotated in the cow. Inclusion of SNPs located in annotated genes and the ‘genomic’ SNPs, many of which are likely to be located in genes, will add a significant number of gene centric markers that will be highly informative for mapping genetic loci for specific phenotypic traits (e.g. 29).

We have identified 36,737 genes with novel exons compared to the annotated bovine genome. Similar to the most highly expressed genes, the list of the most highly expressed genes with novel exons includes genes known to be central to cardiac development and function. In addition to identifying genes expressed in the fetal heart sheep transcriptome, our dataset provides information about the expression of individual isoforms for each gene. Isoform expression patterns may provide unique insights into the fetal transcriptome since it is likely that unique fetal transcript splice variants may play essential roles during development and these variants may not be seen in adult tissues (e.g. Thorsteinsdóttir et al. 1999). Further studies are required to determine if sheep fetal heart exon usage differs from the adult sheep heart as well as the cow. Differences in exon usage between the fetus and the adult would suggest one genetic mechanism allowing for significant variation in the expressed genome through development.

Sheep studies provide unique opportunities for translation of understanding reproductive physiology and mechanisms of development programming to humans. Despite the unique opportunities provided by pregnant sheep as a model, we believe that the lack of genetic and genomic tools has constituted a major barrier to fully realizing the translation power of this model. To establish a metric demonstrating this issue, we conducted a PubMed search on September 6, 2011 using the keyword ‘fetus’ followed by a tissue (e.g. ‘adipose tissue’) and either ‘sheep’ or ‘rodent’ (Table 6). For example the search ‘fetus and sheep’ produced 8094 hits while the search ‘fetus and rodent’ produced 28,563 hits. It is clear that despite their many advantages for translational studies, opportunities in the sheep are generally not being seized. There are numerous factors that contribute to this disparity including the infrastructural resources and environment necessary to support sheep research and the slower ‘throughput’ of studies involving gestation lasting approximately 5 months. How different species manage the biological challenges that underlie developmental programming requires the study of precocial as well as altricial, monotocous as well as polytocous, species. This idea is perhaps best portrayed by the fact that, relative to her own body weight, a rodent mother nurtures a biomass equivalent to a pregnant woman growing a 30 kilogram baby. While there is much to be learned from this level of nutrient challenge in rodents there is also a clear need to compare data obtained from them to data from species such as the sheep that more closely follow the human course of fetal development. Given the challenges of large animal studies, we believe the availability of the information assembled here brings significant added value to the pregnant sheep model, thereby increasing the translational power of both rodent and sheep studies.

Table 6.

Papers in PubMed on developmental programming by species and tissue type

| Tissue | Sheep | Rodent |

|---|---|---|

| Fetus | 8094 | 28563 |

| Fetus± Adipose tissue | 92 | 309 |

| Adrenal | 883 | 1002 |

| Brain | 1252 | 5898 |

| Glucocorticoid | 335 | 692 |

| Heart | 1825 | 2130 |

| Hypothalamus | 364 | 836 |

| Liver | 629 | 5469 |

| Lung | 834 | 2022 |

| Pancreas | 74 | 753 |

| Placenta | 1321 | 3218 |

Our purpose was to produce a resource for ourselves and other investigators to enable the design of genomic tools and to conduct future studies on gene–environment interactions in this important species. Availability of these data will enable further progress in determination of epigenetic changes such as alternative splicing (Luco et al. 2011) and transcription start site variation (Ong & Corces, 2011) and changes in cell signalling such as nutrient sensing in placenta (Roos et al. 2009) and fetal tissues (Nijland et al. 2007). In addition, these tools can be applied to post-natal situations to determine persistence (Steckler et al. 2007) of changes that occurred during development. The high-throughput nature of the technology and associated bioinformatic analytical strategies, such as pathway analyses, will provide important discovery tools that can then be used to design hypothesis-driven, mechanistic studies.

Conclusions

We annotated 9407 coding RNA transcripts aligning sheep RNA-Seq cDNAs to cow RefSeq genes. By aligning the non-annotated, but unique, cDNAs to the cow genome sequence we identified an additional 18,491 novel transcripts. Aligning the remaining transcripts to the human genome sequence increased the number of novel transcripts by a further 9094 transcripts not annotated in either cow or sheep. Comparison of these gene sequences with full-length sheep RefSeq genes showed 259 genes common to both datasets, indicating that 36,737 genes sequenced in this study are novel. Furthermore, we identified 9245 genes (combining all splice variants for a given gene) by aligning the RNA-Seq sheep cDNAs to cow RefSeq genes; 8986 of these genes are novel to sheep. Aligning unmapped, unique cDNAs to the cow genome sequence and the human genome sequence resulted in the annotation of an additional 2969 genes in the sheep fetal heart transcriptome. We also found a total of 981 non-coding RNAs of which 193 are annotated miRNAs and 977 are novel to both cow and sheep.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge technical contributions by Eugene Hopstetter Jr and Olen Sluder Jr. This investigation was supported by NIH NICHD 21350, NIH INBRE P20 RR16474 and conducted in facilities constructed with support from Research Facilities Improvement Program Grant Number C06 RR 1 C06 RR013556 and 1 C06 RR017515 from the National Centre for research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

Glossary

- InDel

insertion-deletion polymorphism

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- miRNA

microRNA

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphisms

- UTR

untranslated region

Author contributions

All authors participated in the design, interpretation of the studies and analysis of the data and review of the manuscript; L.A.C., J.P.G., R.G. and S.P.F. conducted the experiments, L.A.C., J.P.G., and K.D.S. analysed the data, and L.A.C., K.D.S., M.J.N., P.W.N. and S.P.F. wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary material

Supplemental Table S1

Supplemental Table S2

Supplemental Table S3

Supplemental Table S4

Supplemental Table S5

Supplemental Table S6

Supplemental Table S7

Supplemental Table S8

Supplemental Table S9

Supplemental Table S10

References

- Armitage JA, Khan IY, Taylor PD, Nathanielsz PW, Poston L. Developmental programming of the metabolic syndrome by maternal nutritional imbalance: How strong is the evidence from experimental models in mammals? J Physiol. 2004;561:355–377. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.072009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, Harris MA, Hill DP, Issel-Tarver L, Kasarskis A, Lewis S, Matese JC, Richardson JE, Ringwald M, Rubin GM, Sherlock G. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. The gene ontology consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcroft J, Barron DH. The genesis of respiratory movements in the foetus of the sheep. J Physiol. 1936;88:56–61. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1936.sp003422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkin DJ, Yang F, Broad TE, Wienberg J, Hill DF, Ferguson-Smith MA. Use of the indian muntjac idiogram to align conserved chromosomal segments in sheep and human genomes by chromosome painting. Genomics. 1997;46:143–147. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarty A, Roberts MR. Ets-2 and C/ebp-beta are important mediators of ovine trophoblast kunitz domain protein-1 gene expression in trophoblast. BMC Mol Biol. 2007;8:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-8-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford AM, Dodds KG, Ede AJ, Pierson CA, Montgomery GW, Garmonsway HG, Beattie AE, Davies K, Maddox JF, Kappes SW. An autosomal genetic linkage map of the sheep genome. Genetics. 1995;140:703–724. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.2.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalrymple BP, Kirkness EF, Nefedov M, McWilliam S, Ratnakumar A, Barris W, et al. Using comparative genomics to reorder the human genome sequence into a virtual sheep genome. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R152. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-7-r152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, Garimella KV, Maguire JR, Hartl C, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerr MD, Goravanahally MP, Rhinehart JD, Inskeep EK, Flores JA. Effects of endothelin receptor type-A and type-B antagonists on prostaglandin F2α-induced luteolysis of the sheep corpus luteum. Biol Reprod. 2008;78:688–696. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.064105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford SP, Hess BW, Schwope MM, Nijland MJ, Gilbert JS, Vonnahme KA, et al. Maternal undernutrition during early to mid-gestation in the ewe results in altered growth, adiposity, and glucose tolerance in male offspring. J Anim Sci. 2007;85:1285–1294. doi: 10.2527/jas.2005-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford SP, Zhang L, Zhu M, Miller MM, Smith DT, Hess BW, et al. Maternal obesity accelerates fetal pancreatic beta-cell but not alpha-cell development in sheep: Prenatal consequences. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297:R835–R843. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00072.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giussani DA, Fletcher AJ, Gardner DS. Sex differences in the ovine fetal cortisol response to stress. Pediatr Res. 2011;69:118–122. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182042a20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giussani DA, Spencer JA, Hanson MA. Fetal cardiovascular reflex responses to hypoxaemia. Fetal Matern Med Rev. 1994;6:17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Jones S. MiRBase: MicroRNA sequences and annotation. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2010 doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1209s29. Chapter 12 Unit 12.9.1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamosh A, Scott AF, Amberger JS, Bocchini CA, McKusick VA. Online mendelian inheritance in man (OMIM), a knowledgebase of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Database issue):D514–D517. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini P, Tremblay A, Matthews BF, Alkharouf NW. An efficient annotation and gene-expression derivation tool for illumina solexa datasets. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:183. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannuzzi L, Di Meo GP, Perucatti A, Incarnato D. Comparison of the human with the sheep genomes by use of human chromosome-specific painting probes. Mamm Genome. 1999;10:719–723. doi: 10.1007/s003359901078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireland JJ, Roberts RM, Palmer GH, Bauman DE, Bazer FW. A commentary on domestic animals as dual-purpose models that benefit agricultural and biomedical research. J Anim Sci. 2008;86:2797–2805. doi: 10.2527/jas.2008-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Goto S, Kawashima S, Okuno Y, Hattori M. The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Database issue):D277–D280. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ. BLAT – the blast-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12:656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson N, Wood CE. Interaction of PGHS-2 and glutamatergic mechanisms controlling the ovine fetal hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;299:R365–R370. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00163.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25.1–R25.10. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and samtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liggins GC. Premature delivery of foetal lambs infused with glucocorticoids. J Endocrinol. 1969;45:515–523. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0450515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louey S, Jonker SS, Giraud GD, Thornburg KL. Placental insufficiency decreases cell cycle activity and terminal maturation in fetal sheep cardiomyocytes. J Physiol. 2007;580:639–648. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.122200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luco RF, Allo M, Schor IE, Kornblihtt AR, Misteli T. Epigenetics in alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Cell. 2011;144:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald TJ, Nathanielsz PW. Bilateral destruction of the fetal paraventricular nuclei prolongs gestation in sheep. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:764–770. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90325-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, et al. The genome analysis toolkit: A mapreduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen IC, Robinson JS. Developmental origins of the metabolic syndrome: Prediction, plasticity, and programming. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:571–633. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00053.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer AM, Reed JJ, Neville TL, Thorson JF, Maddock-Carlin KR, Taylor JB, et al. Nutritional plane and selenium supply during gestation affect yield and nutrient composition of colostrum and milk in primiparous ewes. J Anim Sci. 2011;89:1627–1639. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore PJ, Nijhuis JG, Hanson MA. The pattern of breathing of fetal sheep in graded hypoxia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1989;31:265–272. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(89)90162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathanielsz PW. Comparative studies on the initiation of labor. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1998;78:127–132. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(98)00058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijland MJ, Schlabritz-Loutsevitch NE, Hubbard GB, Nathanielsz PW, Cox LA. Non-human primate fetal kidney transcriptome analysis indicates mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a central nutrient-responsive pathway. J Physiol. 2007;579:643–656. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.122101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong CT, Corces VG. Enhancer function: New insights into the regulation of tissue-specific gene expression. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:283–293. doi: 10.1038/nrg2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Tierney PF, Anderson DF, Faber JJ, Louey S, Thornburg KL, Giraud GD. Reduced systolic pressure load decreases cell-cycle activity in the fetal sheep heart. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;299:R573–R578. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00754.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poston L. Intrauterine vascular development: Programming effects of nutrition on vascular function in the new born and adult. Nutr Health. 2001;15:207–212. doi: 10.1177/026010600101500409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Maglott DR. NCBI reference sequences (refseq): A curated non-redundant sequence database of genomes, transcripts and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Database issue):D61–D65. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A, Pimentel H, Trapnell C, Pachter L. Identification of novel transcripts in annotated genomes using rna-seq. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2325–2329. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos S, Powell TL, Jansson T. Placental mTOR links maternal nutrient availability to fetal growth. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:295–298. doi: 10.1042/BST0370295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda-Clausen CF, Morton JS, Davidge ST. The early origins of cardiovascular health and disease: Who, when, and how. Semin Reprod Med. 2011;29:197–210. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1275520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Bovine Genome Sequencing and Analysis Consortium. The genome sequence of taurine cattle: A window to ruminant biology and evolution. Science. 2009;324:522. doi: 10.1126/science.1169588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloboda DM, Moss TJ, Li S, Doherty DA, Nitsos I, Challis JR, Newnham JP. Hepatic glucose regulation and metabolism in adult sheep: Effects of prenatal betamethasone. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289:E721–E728. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00040.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steckler T, Manikkam M, Inskeep EK, Padmanabhan V. Developmental programming: Follicular persistence in prenatal testosterone-treated sheep is not programmed by androgenic actions of testosterone. Endocrinology. 2007;148:3532–3540. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsteinsdóttir S, Roelen BA, Goumans MJ, Ward-van Oostwaard D, Gaspar AC, Mummery CL. Expression of the α6A integrin splice variant in developing mouse embryonic stem cell aggregates and correlation with cardiac muscle differentiation. Differentiation. 1999;64:173–184. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1999.6430173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: Discovering splice junctions with rna-seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–1111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by rna-seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotech. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Ma H, Tong C, Zhang H, Lawlis GB, Li Y, et al. Overnutrition and maternal obesity in sheep pregnancy alter the JNK-IRS-1 signaling cascades and cardiac function in the fetal heart. FASEB J. 2010;24:2066–2076. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-142315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson CS, Schaefer R, White SE, Homan JH, Fraher L, Harding R, Bocking AD. Effect of intermittent umbilical cord occlusion on fetal respiratory activity and brain adenosine in late-gestation sheep. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2002;14:35–42. doi: 10.1071/rd01013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu MJ, Han B, Tong J, Ma C, Kimzey JM, Underwood KR, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase signalling pathways are down regulated and skeletal muscle development impaired in fetuses of obese, over-nourished sheep. J Physiol. 2008;586:2651–2664. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.149633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.