Abstract

Protein-losing gastropathy is a rare entity. Unlike the disease in adults, it usually is benign and self-limited in children. The aetiological contribution of cytomegalovirus has been insufficiently documented and the immunological status of patients was rarely described in most reports. The authors report an 11-year-old boy with generalised oedema and hypoproteinemia. Upper endoscopy with biopsies showed marked hypertrophy of gastric folds and foveolar hyperplasia involving the body and fundus. The presence of cytomegalovirus in gastric tissue was well documented through identification of intranuclear inclusions, immunohistochemistry and PCR. Immunodeficiency was clearly ruled out. Protein-losing gastropathy should be considered in children with oedema and hypoproteinemia. The aetiological diagnosis should be confirmed by endoscopy-based methods.

Background

Protein-losing gastropathy (PLG) is characterised by diffuse thickening of the gastric mucosa and histological features of foveolar hyperplasia.1–4 Clinical manifestations include oedema, vomiting, abdominal pain, anorexia and diarrhoea.1 2 Less than 100 paediatric cases have been described so far. Unlike adults, in children it is a transient disorder without long-term complications.3 4 Paediatric PLG associated with cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection has been infrequently reported in literature.1–5 Moreover, the aetiological contribution of CMV has been insufficiently documented and the immunological status of patients was rarely described. We report the case of a child with PLG associated with clearly documented CMV infection and whose immunocompetent status was unequivocally confirmed.

Case presentation

An 11-year-old Caucasian boy presented with a 2 week-history of epigastric pain, vomiting and transient diarrhoea. Two days before admission, symmetrical, pitting oedema of lower limbs was evident, which progressed to the abdominal wall and face within a few days, with weight gain of about 3 kg. There was no fever, jaundice or any other symptoms. The patient was the second child of non-consanguineous parents. Lactose intolerance was diagnosed by hydrogen breath test and the child was on a lactose-restriction diet since 2 years old. The 21-year-old sister was also lactose intolerant. Personal and family history were otherwise unremarkable. There was no history of recent travelling or contact with animals. Physical examination on admission disclosed adequate blood pressure, generalised oedema and moderate tenderness in abdominal upper quadrants, with no evidence of hepatosplenomegaly or ascites. There were no signs of dehydration, jaundice, lymphadenopathy, oropharyngeal swelling/hyperaemia or skin rash.

Investigations

Initial laboratory evaluation revealed hypoproteinemia and hypoalbuminemia (3.2 and 1.4 g/dl, respectively) and slightly raised aspartate and alanine transaminases (84 and 68 U/l; reference range 8–60 and 7–55 U/l, respectively).6 Complete blood count and urinalysis were normal; prothrombin time, γ-glutamyl transferase, alkaline phosphatase, total and direct bilirubin, urea, creatinine, serum electrolytes and C reactive protein were within normal range.

Differential diagnosis

In a child with oedema and hypoalbuminemia, protein loss (either of renal or gastrointestinal origin), hepatic insufficiency or inadequate intake must be considered. In our patient, absence of proteinuria excluded renal loss. Clinical findings, normal prothrombin time and liver enzymes other than transaminases made the other two causes unlikely.

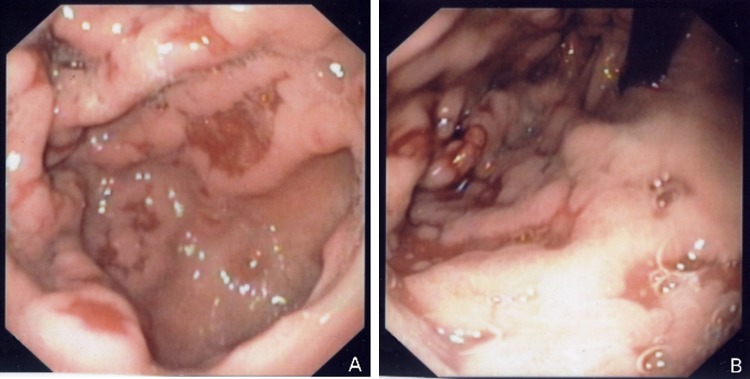

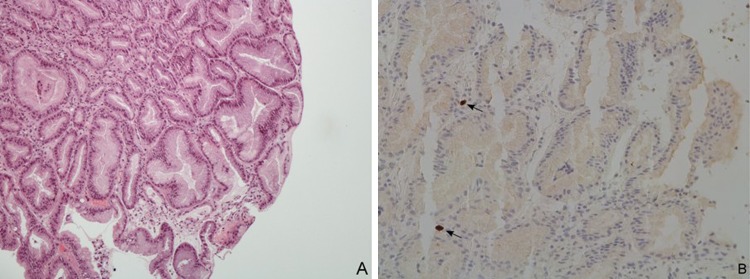

Once admitted to the ward, the hypothesis of PLG was considered. Abdominal ultrasonography showed marked hypertrophy of gastric wall and folds and moderate hepatosplenomegaly (figure 1). Upper endoscopy on 3rd week of disease confirmed moderate hypertrophic gastropathy with erosions affecting the fundus and body (figure 2), while sparing the oesophagus, antrum and duodenum. Multiple biopsies were taken; histological examination of gastric fundus and body revealed foveolar hyperplasia, crypt hypertrophy and lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate (figure 3A). Helicobacter pylori (Giemsa staining and culture of antrum mucosa samples) and herpes simplex virus (HSV, in situ hybridisation) were undetectable. CMV intranuclear inclusions were identified in the fundus and body by H&E staining and immunohistochemistry (figure 3B). Duodenal histology was unremarkable and Giardia lamblia trophozoites were not found. CMV DNA was also detected in gastric tissue by PCR, while being negative for HSV 1 and 2, Epstein–Barr (EBV), varicella-zoster viruses, human herpesvirus 6, enterovirus and adenovirus.

Figure 1.

Abdominal ultrasound, showing marked hypertrophy of gastric wall and folds.

Figure 2.

Upper endoscopy. (A) and (B) Thickened gastric folds with mucosal erosions in fundus and body of stomach, sparing the antrum.

Figure 3.

Light microscopy of gastric biopsy specimens collected from fundus and body. (A) Hyperplasia and cystic dilatation of gastric pits (H&E x200). (B) Cytomegalovirus intranuclear inclusions (arrows) in epithelial cells from gastric body, detected by immunohistochemistry (x200).

Additional investigation included normal faecal α 1-antitrypsin level, negative stool culture and negative serologies for EBV, HSV and HIV, all performed in the third week of disease. Serology for CMV was positive (immunoglobulin G (IgG) 42 UA/ml, immunoglobulin M (IgM) index 1.46 by enzyme-linked fluorescence assay) but viraemia was undetectable. An extensive study of the patient’s immunological status was performed between the 18th and 24th weeks, including quantification of lymphocyte subpopulations, response to mitogens and antigens, complement and immunoglobulin levels, which ruled out immunodeficiency (table 1). Furthermore, expansion of a terminally differentiated subpopulation of CD4+ T cells (CD45RA+CD27-) was shown.

Table 1.

Summary of immunological tests (differential leukocyte count, lymphocyte subpopulations, immunoglobulins and complement)

| Test | Result | Reference range6 14 |

| Leukocytes (×109 cells/l) | 4.46 | 4.0–13.5 |

| Neutrophils (×109 cells/l) | 1.68 | 1.5–8.0 |

| Eosinophils (×109 cells/l) | 0.23 | 0.05–1.0 |

| Basophils (×109 cells/l) | 0.03 | 0.02–0.12 |

| Monocytes (×109 cells/l) | 0.24 | 0.15–1.3 |

| Lymphocytes (×109 cells/l) | 2.27 | 1.5–5.0 |

| CD19+ B lymphocytes | 0.20 | 0.2–0.6 |

| CD3+ T lymphocytes | 1.66 | 0.8–3.5 |

| CD3+/CD4+ T lymphocytes | 0.91 | 0.4–2.1 |

| CD3+/CD8+ T lymphocytes | 0.55 | 0.2–1.2 |

| CD3−/CD16+/CD56+ NK cells | 0.27 | 0.07–1.2 |

| IgM (mg/dl) | 339 | 56–352 |

| IgA (mg/dl) | 75 | 42–295 |

| IgG (mg/dl) | 1010 | 503–1719 |

| IgG1 subclass (mg/dl) | 713 | 280–1030 |

| IgG2 subclass (mg/dl) | 168 | 66–502 |

| IgG3 subclass (mg/dl) | 58 | 11–105 |

| IgG4 subclass (mg/dl) | 31 | 1–122 |

| κ free light chain (mg/dl) | 0.73 | 0.3–1.94 |

| λ free light chain (mg/dl) | 1.18 | 0.57–2.63 |

| κ/λ free light chain ratio | 0.61 | 0.26–1.65 |

| C3 (mg/dl) | 110 | 90–180 |

| C4 (mg/dl) | 28 | 10–40 |

| CH50 (U/ml) | 57.4 | 42–78 |

CD, cluster of differentiation; NK, natural killer; IgM, immunoglobulin M; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IgG, immunoglobulin G.

Outcome and follow-up

At this point, hypertrophic gastropathy associated with CMV infection was the most likely diagnosis. Supportive therapy with intravenous albumin, omeprazole, sucralfate and high-protein diet was instituted. Clinical remission was achieved within the 3rd week of disease, with return to the previous weight (30 kg, 10th to 25th percentile). Transaminases and serum proteins achieved normal levels at 5th and 8th weeks of disease, respectively. Antibodies against CMV slightly increased (IgG 63 UA/ml, IgM index 1.64 at 10th week), although viraemia remained undetectable. Abdominal ultrasound at 3 months follow-up showed significant improvement. At 20 months follow-up, the patient remained asymptomatic.

Discussion

PLG is characterised by hypertrophy of gastric folds and foveolar hyperplasia involving the fundus and body, but usually sparing the antrum.1–4 The aetiology is uncertain. Infectious, allergic and immunologic causes have been postulated. The most frequently reported infectious agents are CMV, Helicobacter pylori, Mycoplasma, herpes virus and Giardia lamblia.

CMV has been reported in only a few case series concerning paediatric PLG.2–5 The disease could be underdiagnosed, as it usually causes little or no symptoms. Males seem to be more frequently affected.1–4 Our patient is older than most cases described in literature, where a peak incidence at 2 to 5 years of age has been reported.1 2 4 The pathogenesis is not fully understood. Host response to CMV is thought to elicit production of transforming growth factor α, leading to epithelial cell proliferation and widening of tight junctions.7 8 These changes cause protein leakage, resulting in hypoproteinemia, hypoalbuminemia and oedema. Faecal α 1-antitrypsin level is usually increased in diseases with gastrointestinal protein loss; however, degradation of this protein by gastric acid may result in misleading normal levels.9

The most common clinical finding in children is oedema.1 2 Hepatosplenomegaly and raised transaminases are an expression of involvement of these organs frequently seen in CMV infection.

Abdominal ultrasonography may be useful at first approach, documenting the characteristic pattern of enlarged gastric folds.7 It has a good correlation with clinical evolution, allowing non-invasive follow-up.7

Upper endoscopy with biopsies is the gold-standard for diagnosis, confirming the hypertrophic gastropathy pattern.1–4 Multiple biopsies are recommended, because CMV inclusions may be difficult to find.1 3 Immunohistochemistry and detection of CMV DNA by PCR on gastric biopsy specimens are sensitive and specific tools.2 3 5 The latter may offer advantage when other methods fail to identify the virus.

In a review by Occena et al, CMV was demonstrated in gastric tissue in 33% of cases.1 The role of CMV in the present case was well documented by PCR detection of DNA, identification of intranuclear inclusions and immunohistochemistry in gastric mucosa. Serology interpretation may be difficult, especially in the presence of hypogammaglobulinaemia due to protein loss. In our patient, CMV antibody titres were not impressively raised and clear seroconversion was not observed. These data, and the undetectable viraemia in two determinations, support a predominantly gastrointestinal involvement, with little systemic expression.

CMV is a ubiquitous virus, usually causing disease in immunocompromised hosts. However, there have been rare reports of PLG associated with CMV in presumably immunocompetent children, although immunological status has seldom been documented.10 In our patient, immunodeficiency was clearly ruled out. The investigation of the immunological status revealed expansion of a terminally differentiated subpopulation of CD4+ T cells (CD45RA+CD27−), which has been associated with past CMV infection.11

Natural history remains unclear. Despite its protracted course with risk of malignancy in adults, it usually is self-limited in children.3 4 Although some authors recommend follow-up endoscopy with biopsies to document eradication of the virus from gastric mucosa,8 the cost-effectiveness of this procedure is not consensual. Considering the complete clinical resolution after several months of follow-up, we did not perform a second endoscopy.

Most paediatric patients recover spontaneously or with supportive treatment, such as intravenous albumin, high-protein diet and drugs for protection of gastric mucosa.1 3 4 8 Antiviral therapy with ganciclovir is rarely required in immunocompetent children and is usually reserved for immunocompromised hosts, newborns and children with severe clinical courses (namely with neurological involvement) or who do not improve with supportive treatment.2 10 Moreover, the potential serious adverse effects of this drug (myeolosupression, renal toxicity, infertility) must be taken into consideration.12 The putative benefit of antiviral treatment in visceral CMV infection in immunocompetent subjects is largely speculative, considering that its natural history is uncertain and advances in medical care have favourably changed clinical outcome.1 3 4 8 Interestingly, the first report of CMV-associated PLG in an adult immunocompetent patient not requiring antiviral treatment has recently been published.13 Our patient had a very favourable outcome under supportive treatment within the expected time delay, with complete clinical resolution by 3rd week of disease, no evidence of other organ involvement besides moderate fundus/corpus gastropathy and hepatomegaly nor associated complications. Therefore, on an individual risk-efficacy evaluation, it was considered that the institution of antiviral therapy would add no additional benefit to the patient.

Learning points.

PLG should be suspected in children with oedema and hypoproteinemia, after ruling out renal and hepatic causes.

Diagnostic investigation should include endoscopy with multiple biopsies and immunological evaluation, as it may influence treatment decision.

PCR detection of CMV in gastric mucosa may be helpful, given the limited value of other methods.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Occena RO, Taylor SF, Robinson CC, et al. Association of cytomegalovirus with Ménétrier’s disease in childhood: report of two new cases with a review of literature. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1993;17:217–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Megged O, Schlesinger Y. Cytomegalovirus-associated protein-losing gastropathy in childhood. Eur J Pediatr 2008;167:1217–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sferra TJ, Pawel BR, Qualman SJ, et al. Ménétrier disease of childhood: role of cytomegalovirus and transforming growth factor alpha. J Pediatr 1996;128:213–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marks MP, Lanza MV, Kahlstrom EJ, et al. Pediatric hypertrophic gastropathy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1986;147:1031–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ricci S, Bonucci A, Fabiani E, et al. [Protein-losing gastroenteropathy (Ménétrier’s disease) in childhood: a report of 3 cases]. Pediatr Med Chir 1996;18:269–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pediatric Test Reference Values [internet]. 2012 [cited 2012 Feb 16]. Available from http://www.mayomedicallaboratories.com/test-info/pediatric/refvalues/reference.php

- 7.Takaya J, Kawamura Y, Kino M, et al. Ménétrier’s disease evaluated serially by abdominal ultrasonography. Pediatr Radiol 1997;27:178–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oderda G, Cinti S, Cangiotti AM, et al. Increased tight junction width in two children with Ménétrier’s disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1990;11:123–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milovic V, Grand RJ. Protein-losing gastroenteropathy. In: Basow DS, ed. Waltham: UpToDate 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwanaga M, Zaitsu M, Ishii E, et al. Protein-losing gastroenteropathy and retinitis associated with cytomegalovirus infection in an immunocompetent infant: a case report. Eur J Pediatr 2004;163:81–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Libri V, Azevedo RI, Jackson SE, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection induces the accumulation of short-lived, multifunctional CD4+CD45RA+CD27+ T cells: the potential involvement of interleukin-7 in this process. Immunology 2011;132:326–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobson MA. Ganciclovir therapy for severe cytomegalovirus infection in immunocompetent patients. Clin Infect Dis 1997;25:1487–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suter WR, Neuweiler J, Borovicka J, et al. Cytomegalovirus-induced transient protein-losing hypertrophic gastropathy in an immunocompetent adult. Digestion 2000;62:276–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Comans-Bitter WM, de Groot R, van den Beemd R, et al. Immunophenotyping of blood lymphocytes in childhood. Reference values for lymphocyte subpopulations. J Pediatr 1997;130:388–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]