Abstract

Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis (PPV) is a rare sporadic genetic disorder characterised by co-occurrence of an extensive vascular nevus and a large pigmentary nevus with or without extracutaneous manifestations. There are four types of PPV with subtype ‘a’ for cutaneous involvement only and subtype ‘b’ for cutaneous and systemic involvement. PPV type IIa consists of nevus flammeus, Mongolian spots and sometimes nevus anemicus. Prognosis depends on associated systemic disorders. Two independent cases of PPV type IIb presented with nevus flammeus, aberrant Mongolian spots, ocular and central nervous system anomalies. Case 1 had external hydrocephalus previously unreported in PPV while case 2 had hydrocephalus exvacuo. Both patients had seizure disorder and neurodevelopmental delay. They were on long-term neurologic and ophthalmologic management while their cutaneous lesions partially regressed. PPV affects all racial and ethnic groups. The occurrence of external hydrocephalus in PPV expands the spectrum of its systemic manifestations.

Background

Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis (PPV) type IIb has not been previously reported in Africans in the West African subregion, to our knowledge. The presence of external hydrocephalus (EH) in case 1 expands the spectrum of systemic manifestations in PPV; it also highlights the possibility of dual rarities coexisting in the same patient.

Case presentation

Two unrelated cases of PPV typeIIb were seen at the Department of Child Health, University of Benin Teaching Hospital, Benin city, Edo state, Southern Nigeria between June 2010 and April 2011. They both had extensive capillary malformations, aberrant Mongolian spots, ocular and significant central nervous system (CNS) anomalies. There was no family history of a similar disorder.

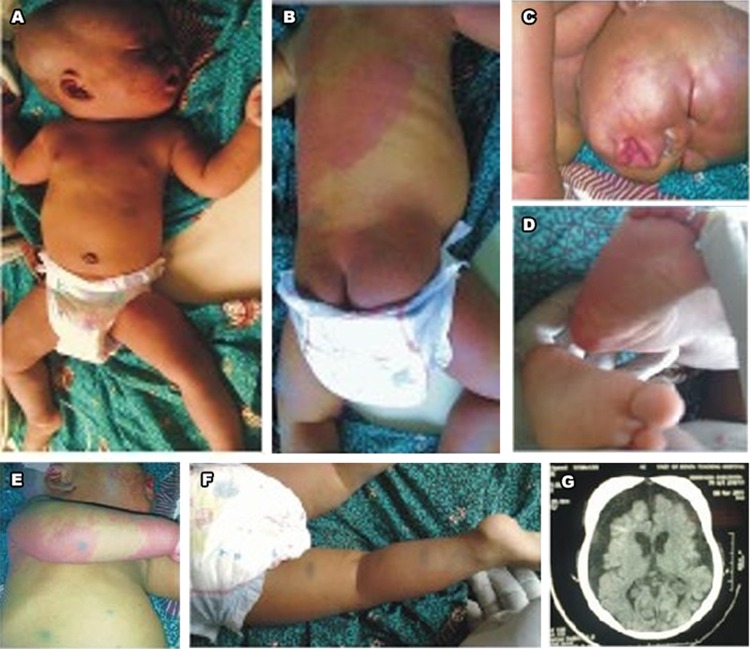

Case 1: a 9-month-old infant was referred from a private clinic to our facility due to macrocephaly, delayed gross motor development and seizure disorder. He had generalised tonic convulsion, occurring on the average three times a month since the onset at the age of 7 months. Pregnancy was normal and he was delivered at 40 weeks gestation age by caesarian section due to cephalopelvic disproportion. Birth weight was 3.8 kilograms, length 50 centimetres and occipitofrontal circumference was 39 centimetres (97th percentile). He had extensive nevus flammeus involving the upper chest, about half of the back and extremities interspersed with Mongolian spots (figure 1A,B). The nevus flammeus also affected the right side of the face (figure 1C), right leg posteriorly extending to the sole of the right foot (figure 1B,D) and right forearm circumferentially merging into a nevus anemicus posteriorly (figure 1E). There is upper limb asymmetry, the right upper limb being 1.5 centimetres larger than the left due to soft tissue hypertrophy without venous varicosities or limb length descripancy. He had melanosis oculi and glaucoma.

Figure 1.

Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis (PPV) type IIb in a 9-month-old African boy; (A): nevus flammeus and aberrant Mongolian spots on the face, trunk and extremities; (B) a large nevus flammeus on the back and buttock with Mongolian spots; (C) nevus flammeus on the face; (D) nevus flammeus on the sole of the right foot; (E) nevus flammeus, nevus anemicus and Mongolian spots on the right forearm; (F) Mongolian spots on the ventral surface of the left lower limb; (G) Cranial CT scan of the same patient showing external hydrocephalus and calcification in the frontoparietal cortex.

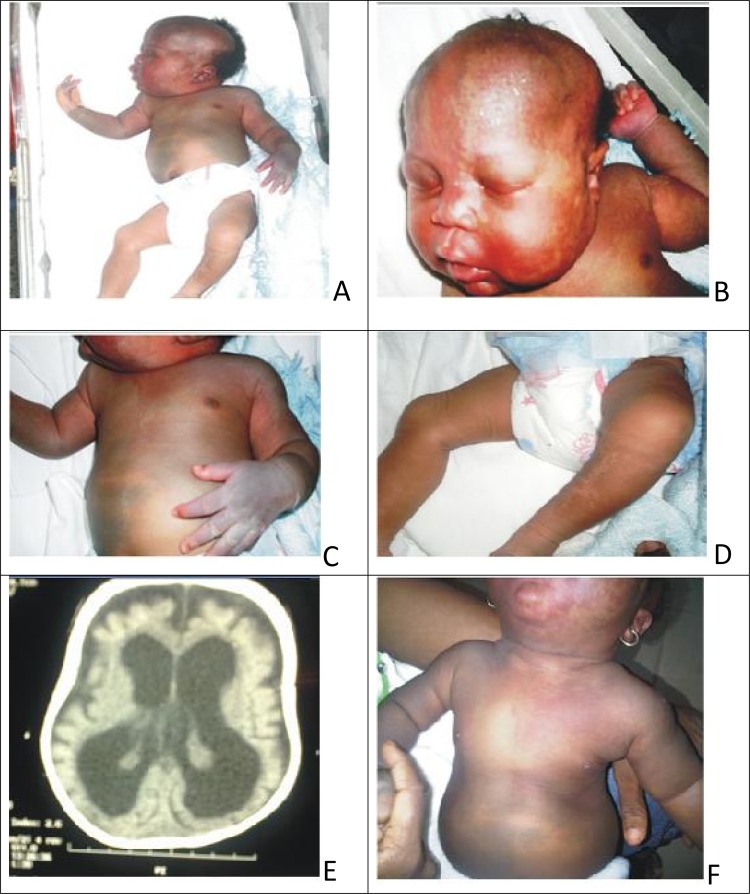

Case 2: a female newborn delivered to a multiparous mother via emergency caesarian section indication being fetopelvic disproportion in a breach presentation. Antenatal period was uneventful. Birth parameters were within normal range as follows: weight 3.9 kilograms, length 51 centimetres and occipitofrontal circumference (OFC) was 37 centimetres. However, she had macrocephaly later in infancy with serial OFC’s greater than 95th percentile for age and sex. She had widespread Mongolian spots involving the abdomen, chest, back/buttocks, posterior forearms and dorsum of the left hand (figure 2A,C). There was nevus flameus on the face, scalp, upper part of the chest and the left palm (figure 2A,B); and nevus anemicus on the medial surface of the left leg (figure 2D). There was soft tissue hypertrophy of the right upper limb with its circumference 2 centimetres greater than the left, but there was no limb length discrepancy or varicose veins.

Figure 2.

(A–D) Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type 2b in a 3-day-old female neonate; (A):nevus flammeus on the face and extensive Mongolian spots on the trunk; (B): nevus flammeus on her face bilaterally, and upper chest; (C): aberrant Mongolian spots on her trunk and extremities; (D): nevus anemicus on the medial surface of the left leg; (E): cranial CT scan of the same patient showing cerebral cerebral atrophy, hydrocephalus exvacuo, calcification in the frontal cortex; (F): fading of the skin lesions at the age of 9 months.

Investigations

Case 1: cranial CT scan (figure 1G) showed cerebral calcification in the right frontoparietal region and marked accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the subarachnoid space bifrontally and widened interhemispheric fissure frontally with only mild enlargement of the rest of the subarachnoid space. There was no significant ventricular dilatation. This is radiologic evidence of EH.

Case 2: cranial CT scan (figure 2E) showed cortical atrophy, subcortical calcification in the parietal region and apparent dilatation of the ventricles consistent with hydrocephalus exvacuo. There was no evidence of cerebral angiomatosis on the scanogram.

Echocardiography confirmed an asymptomatic 3 millimetres atrial septal defect, secondum type. Plain radiographs of the upper limbs excluded bone hypertrophy.

Differential diagnosis

Sturge Weber syndrome (SWS)

Klippel Trenauney syndrome (KTS).

Treatment

Anticonvulsant (syrup carbamazepine 10 mg/kg/day); acetazolamide; physiotherapy/occupational therapy.

Outcome and follow-up

Both patients had bilateral glaucoma, seizures and delayed motor milestones in infancy. Their height and weight were normal at the age of 9 months and cutaneous lesions were fading (figure 2F). They were on conservative management and follow-up in our neurology outpatient clinic.

Discussion

There is a dearth of reports of PPV from West African subcontinent in the literature. About 200 cases have been reported worldwide.1 2 There are four types of PPV, all having nevus flammeus in common.3 In addition, type I has nevus pigmenosus/verrucosus; type II: Mongolian spots; type III: nevus spilus and type IV: Mongolian spots and nevus spilus. Type II–IV may be associated with nevus anemicus.3 Our patients present with extensive port-wine stain, nevus anemicus, aberrant Mongolian spots, glaucoma, CNS anomaly and other extracutaneous features which are consistent with PPV type IIb following the original description of PPV.1 3 They may also be reclassified as phacomatosis cesioflammea using the revised criteria by Happle et al.4 PPV may reflect twin spotting phenomenon (didymosis) due to hypothetic allelic mutation presenting as paired melanocytic and achromic macules or nevus vascularis mixtus.5–7

EH occurs in association with PPV in our first patient. The disproportionate bifrontal widening of the subarachnoid space due to marked CSF accumulation without significant ventricular dilatation (figure 1E) in this infant with macrocephaly fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of EH.8 It presents in early childhood alongside other disorders like prematurity, subdural haematomas, intraventricular haemorrhages and genetic syndromes like Soto’s syndrome and Goldenhar syndrome.8–11 However, the occurrence of EH in association with PPV as found in this case has not been previously reported. This may open a new vista in defining the nature of the association between PPV and hydrocephalus. Neveling et al12 showed delayed absorption of CSF in the infants with idiopathic EH by means of isotope cisternography. Considering that the leptomeninges (alongside melanocytes and vasoactive nerves) are derived from the neural crest cells, we suggest that an intrinsic defect in the arachnoid villi compromises their absorptive capacity in PPV leading to EH in infancy.8 Although the rarity of EH in PPV negates this assertion, this may be due to variable phenotypic expression of the defect among patients. More reports are needed to fully define the nature of this association.

Hall et al13 reported SWS and KTS as being frequently associated with the systemic forms of PPV.13 SWS is often associated with port-wine stains on the face, ipsilateral leptomeningeal angioma, seizures and mental retardation while KTS is a triad of cutaneous and visceral haemangiomas, venous varicosities and soft tissue or bone hypertrophy.13 14 Rarely, concurrence of SWS and KTS in PPV has been described in the literature.15 Clinical evaluation and neuroimaging clearly excluded these co-morbidites in our patients who had no leptomeningeal angioma and unilateral cerebral atrophy typically found in SWS.13 Also, although there is limb hypertrophy, they had neither limb length discrepancy nor underlying vascular malformations found in KTS.14

Atrial septal defect, found in our second patient, is a rare manifestation of PPV.16 It may due to defective conotruncal cells which, like melanocytes, are neural crest cell derivatives. Hence, extensive cutaneous features may reflect significant multi-systemic involvement in PPV as in these cases.

Learning points.

PPV affects all racial and ethnic groups.

The spectrum of systemic manifestations in PPV type IIb includes EH.

Prognosis in PPV depends largely on its extracutaneous features.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Nyan.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

References

- 1.Ota M, Kawamura T, Ito N. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis. Jpn J Dermatol 1947;52:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vidaurri-de la Cruz H, Tamayo-Sánchez L, Durán-McKinster C, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis II A and II B: clinical findings in 24 patients. J Dermatol 2003;30:381–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasegawa Y, Yasuhara M. A variant of phakomatosis pigmentovascularis. Skin Res 1979;21:178–86. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol 2005;141:385–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de las Heras E, Boixeda JP, Ledo A, et al. Paired melanotic and achromic macules in a case of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis: a further example of twin spotting? Am J Med Genet 1997;70:336–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Requena L, Sangueza OP. Cutaneous vascular anomalies. Part I. Hamartomas, malformations, and dilation of preexisting vessels. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997;37:523–49; quiz 549–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahkami RN, Schwartz RA. Nevus anemicus. Dermatology (Basel) 1999;198:327–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maytal J, Alvarez LA, Elkin CM, et al. External hydrocephalus: radiologic spectrum and differentiation from cerebral atrophy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1987;148:1223–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapman PH. External hydrocephalus. Concepts Pediatr Neurosurg 1983;4:102–18. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alvarez LA, Maytal J, Shinnar S. Idiopathic external hydrocephalus: natural history and relationship to benign familial macrocephaly. Pediatrics 1986;77:901–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ment LR, Duncan CC, Geehr R. Benign enlargement of the subarachnoid spaces in the infant. J Neurosurg 1981;54:504–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neveling EA, Truex RC., JrExternal obstructive hydrocephalus: a study of clinical and developmental aspects in ten children. J Neurosurg Nurs 1983;15:255–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall BD, Cadle RG, Morrill-Cornelius SM, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis: Implications for severity with special reference to Mongolian spots associated with Sturge–Weber and Klippel–Trenaunay syndromes. Am J Med Genet Part A 2008;146A:945–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barek L, Ledor S, Ledor K. The Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. Mt Sinai J Med 1982;49:66–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee CW, Choi DY, Oh YG, et al. An infantile case of Sturge-Weber syndrome in association with Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome and phakomatosis pigmentovascularis. J Korean Med Sci 2005;20:1082–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang BP, Hsu CH, Chen HC, et al. An infant with extensive Mongolian spot, naevus flammeus and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita: a unique case of phakomatosis pigmentovascularis. Br J Dermatol 2007;156:1068–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]