Methods & results

Immunotherapy targets antigens that are overexpressed or selectively expressed on tumors in order to counteract the lack of specificity and general toxicity induced by chemotherapy and radiotherapy in the treatment of cancers. Researchers have attempted to focus the power of the immune system on tumor targets in several different ways: first, monoclonal antibodies such as anti-CD20, now a major therapy of non-Hodgkin lymphomas; and second, dendritic cells, the most potent antigen-presenting cells, can express high levels of specific tumor antigens in order to prime T cells to lyse tumors.

Tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes can be directed against overexpressed differentiation antigens on tumors. Another approach to enhance specificity is T-cell receptor (TCR) gene therapy, which transfers TCR genes that recognize protein antigens expressed uniquely or primarily on the surface of tumor cells. This approach is attractive because it does not rely on the expansion of a small number of cells that are specific to a tumor antigen. Additional enhancements to TCR gene therapy include the use of nonmyeloablative conditioning to permit further expansion of transduced cells; the administration of high-dose IL-2, a T-cell growth factor; and the development of TCR transgenes with high affinity for the tumor antigen. One potential drawback of a TCR gene therapy approach is the development of autoimmunity, which may occur for a number of reasons. First, most tumor-associated antigens are also expressed by normal tissues and, thus, large numbers of effector cells swamp normal immunoregulatory mechanisms. Second, T cells with low affinity for self-antigens may cause autoimmunity when the TCR has a higher affinity. Third cross-pairing of endogenous and transduced TCR chains can form mixed dimers, which may produce self-reactive T cells. In a recent article, Bendle et al. demonstrated that transduced TCR chains can pair with endogenous TCR chains and the ‘neo-TCR’a loses its specificity for the tumor antigen and gains specificity for normal recipient tissues [1]. This formation of a neo-TCR from the pairing of mixed dimers may result in severe graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). GVHD is normally mediated by donor T cells that respond to and destroy defined proteins on host cells. The most important target proteins of GVHD are the HLAs, which are highly polymorphic and are encoded by the MHC. Class I HLA (A, B and C) proteins are expressed on almost all nucleated cells. Class II proteins (DR, DQ and DP) are expressed on hematopoietic cells, but their expression can also be induced on other cell types during inflammation [2].

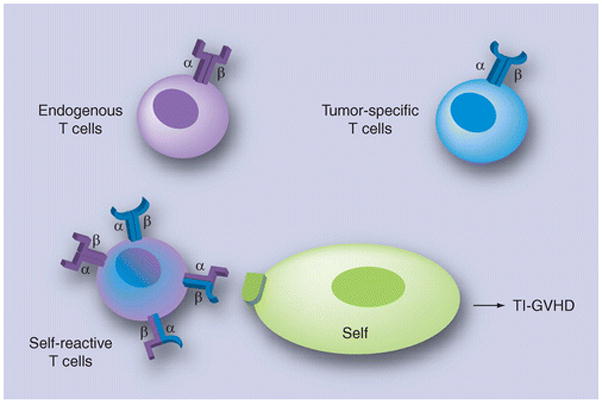

Bendle et al. demonstrated that GVHD can occur after adoptive transfer of T cells modified with transgenic TCRs [1]. TCRs consist of two chains: an [alpha]-chain and a [beta]-chain. A T cell expresses several thousand TCRs with a single specificity, comprised of identical [alpha]- and [beta]-chains. When a second TCR is introduced by gene transfer, an endogenous [alpha]-chain can pair with a transduced [beta]-chain to produce a mixed dimer and vice versa. Figure 1 shows the formation of mixed TCR dimers. In this study, the investigators introduced a transgenic [alpha]- and [beta]-TCR directed against ovalbumin (OT-I TCR) into T cells and transferred them into syngenic recipients after lymphodepletion by sublethal total-body irradiation [1]. High-dose IL-2 further amplified expansion of the transferred T cells following lymphopenia-induced T-cell proliferation [3]. Surprisingly, the recipients exhibited weight loss, destruction of the bone marrow and secondary lymphoid organs and development of colitis and pancreatitis - all features of GVHD. A comparison of OT-I TCR -transduced T cells, OT-I TCR transgenic T cells and green fluorescent protein-transduced T cells showed that the T cells mediating the lethal autoimmune disease were not transgenic OT-I T cells, but cells with transduced OT-I TCR. To test if the T cells mediating this pathology required the association of exogenous and endogenous TCR chains, Bendle et al. transferred either the OT-I TCR [alpha]-chain or OT-I TCR [beta]I2-chain into T cells and observed the effect with each TCR chain alone. When the OT-I TCR [alpha]-chain was depleted in vivo prior to IL-2 administration, they protected the mice.

Figure 1. Each T lymphocyte expresses, on their surface, numerous T-cell receptors, each composed of [alpha] and [beta] chains.

The tumor-specific T cells have been generated by the transfer of transgenic T-cell receptors (TCRs). Rarely, a T cell that received an [alpha]- or [beta]-chain of the endogenous T cells that have cross-paired with the [alpha]- or [beta]-chain of the transgenic TCR will become self-reactive and provoke the TCR gene TI-GVHD pathology.

TI-GVHD: Transfer-induced graft-versus-host disease.

The pathogenesis of this TCR gene-transfer-induced GVHD (TI-GVHD) was mediated by inflammatory cytokines, particularly IFN-7ggr;, since mice receiving transduced OT-I TCR T cells from IFN-7ggr; knockout mice survived. The authors observed that lethal TI-GVHD was seen with multiple tumoral and viral TCRs (Pmel-1, TRP2, SV40IV and influenza A-F5), although the incidence of lethal pathology varied from low (Pmel-1 and influenza A-F5) to high (TRP2 and SV40IV). Low-dose IL-2, together with transduced T cells, induced lethal TI-GVHD in half of the mice, while the remaining mice developed a chronic form of GVHD, characterized by chronic colitis and lymphopenia. Blockade of TGF-[beta] signaling, another strategy to promote the in vivo function of transduced cells (without IL-2 administration) [4,5] also induced the disease.

The researchers sought to limit the disease by transducing the TCR into oligo- or mono-clonal T-cell populations, in order to limit the number of endogenous self-reactive TCRs and, therefore, limit their cross-pairing and formation of mixed dimers [6,7]. Using this approach to reduce the number of endogenous TCRs completely prevented TI-GVHD. A second approach to prevent cross-pairing was to engineer the TCR with an additional disulfide bond between the constant domains of the TCR [alpha]- and [beta]I2-chains [8,9]; this strategy also limited TI-GVHD. A third approach was to generate retroviral vectors in which the internal ribosomal entry site was replaced by a porcine teschovirus-derived P2A sequence to ensure equimolar production of the transduced TCR [alpha]- and [beta]I2-chains [10]. This third approach also further reduced TI-GVHD [1].

Conclusion & future perspective

Transfer-induced GVHD manifests itself as transfusion-associated GVHD in immunocompromised or immunocompetent patients. Infused donor leukocytes, which are haploidentical to HLA of the recipient, will recognize the recipient immune system and will induce GVHD that destroys host hematopoietic cells in the bone marrow and spleen. Transfusion-associated GVHD progresses rapidly, is almost always lethal and is resistant to all treatment [11,12]. Therefore, recognizing and preventing this rare complication is fundamental. Transfusion-associated GVHD has been prevented by using irradiated blood products, although cases of fatal transfusion-associated GVHD from nonirradiated, fresh, whole blood are still reported [13].

To date, TI-GVHD has not been observed in the two clinical trials after adoptive transfer of transgenic T cells [14,15]. According to Bendle et al., the absence of such a phenomenon in patients is caused by the fact that the transgenic T cells were expanded ex vivo for 2–3 weeks before infusion [1]. These expanded T cells have decreased cytotoxicity in vivo [16–18]. Although TI-GVHD is a rare occurrence, it is lethal. Therefore, future clinical studies must demonstrate caution in order to limit the risk of the development of mixed dimers by using one of the three approaches mentioned previously [6–8]. A fourth approach is to use chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) [19]. CARs are composed of a specific antigen-binding domain encoding the variable regions of a monoclonal antibody and are linked together as a single-chain antibody (scFv) molecule, and a signaling molecule derived from either the ζ-chain of the TCR-CD3 complex or the γ-chain of the FceRI receptor. In the newer generation of CARs, one or two additional co-stimulatory molecules, such as CD28, 4-1BB or OX40, are also transduced [19]. This second part forms the receptor endodomains. CARs that are transferred into T cells bind the specific antigen expressed on the cell surface of the target cells through the scFv, and activate the lytic pathway of the T cells by cross-linking the ζ- or γ-OT-chain. Pule et al. have recently demonstrated that infusion of Epstein-Barr virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) expressing a chimeric GD2-specific receptor in patients with neuroblastoma was safe, and was associated with tumor regression or necrosis in half of the subjects tested [20]. Another approach to enhance safety is by transferring a gene that can destroy the T cells upon administration of a triggering drug, such as the viral thymidine kinase [21] or the caspase systems [22].

Cancer immunotherapy with adoptive transfer of tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes induces objective clinical responses in up to 50% of patients with melanoma who are treated with this therapy [23]. This therapy was more effective with immunodepletion prior to the transfer, which resulted in clonal expansion of the transferred T cells and depletion of regulatory T cells. However, this approach has been limited in other cancers because of the low numbers and affinity of the tumor-reactive T cells. The ability to genetically engineer human lymphocytes has led to the emergence of gene transfer of peptide-specific [alpha][beta]I2-TCRs or CARs, both of which can redirect the specificity of polyclonal T cells to a single target on various tumors. These two approaches generate large numbers of specific CTLs that can mediate tumor regression in patients [14,15,20]. As demonstrated by Bendle et al., in theory, TCR gene therapy could be compromised by lethal GVHD [1]. The mechanism of this TCR gene TI-GVHD is the formation of mixed dimers composed of one chain from the exogenous TCR and the second chain from the endogenous TCR; this mixed dimer recognizes host self-tissues. Although this phenomenon has not yet been observed in clinical trials [14,15], preventative approaches, such as addition of a disulfide bond between the TCR [alpha]- and [beta]-constant domains, or the transduction of a TCR into oligoclonal or monoclonal T-cell populations with fewer endogenous TCR genes, will provide an additional measure of safety.

Executive summary.

Immunotherapy with adoptive transfer of autologous tumor-reactive T cells after an immunodepletion preparative regimen is efficient in melanoma patients. However, this approach has been limited for patients with other cancers owing to the low numbers and affinity of these tumor-reactive T cells.

Recent advances in T-cell receptor (TCR) gene transfer allow for increased specificity, affinity and numbers of T cells available for adoptive transfer.

The article under investigation revealed a potential major risk of developing lethal graft-versus-host disease as a result of the cross-pairing of endogenous and transduced TCR chains, which may produce self-reactive T cells. This observation calls for preventative approaches such as the addition of a disulfide bond between the TCR-[alpha] and -[beta] constant domains, or the transduction of a TCR into oligoclonal or monoclonal T-cell populations.

Acknowledgments

Financial: NIH grants P01-CA039542-20 and RC1-HL-101102

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have received NIH grants P01-CA039542-20 and RC1-HL-101102. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Bibliography

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: * of interest ** of considerable interest

- 1**.Bendle GM, Linnemann C, Hooijkaas AI, et al. Lethal graft-versus-host disease in mouse models of T cell receptor gene therapy. Nat Med. 2010;16(5):565–570. doi: 10.1038/nm.2128. Adoptive transfer of rearranged T-cell receptor (TCR) [alpha]- and [beta]I2-chains can produce mixed dimers with endogeneous TCRs that are reactive to self antigens and can cause lethal graft-versus-host disease. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krensky AM, Weiss A, Crabtree G, Davis MM, Parham P. T-lymphocyte-antigen interactions in transplant rejection. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(8):510–517. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199002223220805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donohue JH, Rosenstein M, Chang AE, Lotze MT, Robb RJ, Rosenberg SA. The systemic administration of purified interleukin 2 enhances the ability of sensitized murine lymphocytes to cure a disseminated syngeneic lymphoma. J Immunol. 1984;132(4):2123–2128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas DA, Massague J. TGF-[beta]I2 directly targets cytotoxic T cell functions during tumor evasion of immune surveillance. Cancer Cell. 2005;8(5):369–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5*.Gorelik L, Flavell RA. Immune-mediated eradication of tumors through the blockade of transforming growth factor-[beta]I2 signaling in T cells. Nat Med. 2001;7(10):1118–1122. doi: 10.1038/nm1001-1118. Blockade of TGF-[beta]I2 signaling in T cells can generate antitumor responses in vivo. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heemskerk MH, Hoogeboom M, Hagedoorn R, Kester MG, Willemze R, Falkenburg JH. Reprogramming of virus-specific T cells into leukemia-reactive T cells using T cell receptor gene transfer. J Exp Med. 2004;199(7):885–894. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinhold M, Sommermeyer D, Uckert W, Blankenstein T. Dual T cell receptor expressing CD8+ T cells with tumor-and self-specificity can inhibit tumor growth without causing severe autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2007;179(8):5534–5542. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuball J, Dossett ML, Wolfl M, et al. Facilitating matched pairing and expression of TCR chains introduced into human T cells. Blood. 2007;109(6):2331–2338. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-023069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen CJ, Li YF, El-Gamil M, Robbins PF, Rosenberg SA, Morgan RA. Enhanced antitumor activity of T cells engineered to express T-cell receptors with a second disulfide bond. Cancer Res. 2007;67(8):3898–3903. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Felipe P, Martin V, Cortes ML, Ryan M, Izquierdo M. Use of the 2a sequence from foot-and-mouth disease virus in the generation of retroviral vectors for gene therapy. Gene Ther. 1999;6(2):198–208. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenbaum BH. Transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease: historical perspectives, incidence, and current use of irradiated blood products. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9(10):1889–1902. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.10.1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12*.Schroeder ML. Transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease. Br J Haematol. 2002;117(2):275–287. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03450.x. Good review of the clinical and pathophysiologic aspects of transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agbaht K, Altintas ND, Topeli A, Gokoz O, Ozcebe O. Transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease in immunocompetent patients: case series and review of the literature. Transfusion. 2007;47(8):1405–1411. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14*.Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, et al. Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes. Science. 2006;314(5796):126–129. doi: 10.1126/science.1129003. Long-term survival of T cells transduced with melanoma-specific TCRs in two patients with objective tumor regression. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson LA, Morgan RA, Dudley ME, et al. Gene therapy with human and mouse T-cell receptors mediates cancer regression and targets normal tissues expressing cognate antigen. Blood. 2009;114(3):535–546. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolen S, Dolstra H, Van De Locht L, et al. Biodistribution and retention time of retrovirally labeled T lymphocytes in mice is strongly influenced by the culture period before infusion. J Immunother. 2002;25(5):385–395. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gattinoni L, Klebanoff CA, Palmer DC, et al. Acquisition of full effector function in vitro paradoxically impairs the in vivo antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(6):1616–1626. doi: 10.1172/JCI24480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou J, Shen X, Huang J, Hodes RJ, Rosenberg SA, Robbins PF. Telomere length of transferred lymphocytes correlates with in vivo persistence and tumor regression in melanoma patients receiving cell transfer therapy. J Immunol. 2005;175(10):7046–7052. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.7046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dotti G, Savoldo B, Brenner M. Fifteen years of gene therapy based on chimeric antigen receptors: ‘are we nearly there yet?’. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20(11):1229–1239. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20**.Pule MA, Savoldo B, Myers GD, et al. Virus-specific T cells engineered to coexpress tumor-specific receptors: persistence and antitumor activity in individuals with neuroblastoma. Nat Med. 2008;14(11):1264–1270. doi: 10.1038/nm.1882. Phase I/II trial of Epstein-Barr virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes engineered to express a chimeric GD2-specific receptor in patients with neuroblastoma that expressed GD2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ciceri F, Bonini C, Stanghellini MT, et al. Infusion of suicide-gene-engineered donor lymphocytes after family haploidentical haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation for leukaemia (the TK007 trial): a non-randomised Phase I-II study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(5):489–500. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoyos V, Savoldo B, Quintarelli C, et al. Engineering CD19-specific T lymphocytes with interleukin-15 and a suicide gene to enhance their anti-lymphoma/leukemia effects and safety. Leukemia. 2010;24(6):1160–1170. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP, Yang JC, Morgan RA, Dudley ME. Adoptive cell transfer: a clinical path to effective cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(4):299–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]