Abstract

Pompe disease is an autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disorder (LSD) caused by deficiency of the lysosomal enzyme acid alpha glucosidase (GAA). Many disease-causing mutated GAA retain enzymatic activity, but are not translocated from endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to lysosomes. Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) is the only treatment for Pompe disease, but remains expensive, inconvenient and does not reverse all disease manifestations. It was postulated that small molecules which aid in protein folding and translocation to lysosomes could provide an alternate to ERT. Previously, several iminosugars have been proposed as small-molecule chaperones for specific LSDs. Here we identified a novel series of non-iminosugar chaperones for GAA. These moderate GAA inhibitors are shown to bind and thermo-stabilize GAA, and increase GAA translocation to lysosomes in both wild-type and Pompe fibroblasts. AMDE and physical properties studies indicate that this series is a promising lead for further pharmacokinetic evaluation and testing in Pompe disease models.

INTRODUCTION

LSDs represent over 50 different rare diseases and result from mutations in lysosomal enzymes. Phenotypically, cells affected by LSDs are characterized by lysosomal enlargement due to accumulation of disease-specific substrates.1 Pompe disease, also known as glycogen storage disease type II or acid maltase deficiency, is an autosomal recessive LSD caused by mutations in the lysosomal enzyme GAA2 with a frequency of approximately 1 in every 40,000 births.3 Disease progression is variable and clinical symptoms can include progressive muscle weakness and loss of motor, respiratory, and cardiac function. In most patients, premature death occurs due to respiratory complications. GAA hydrolyzes the terminal alpha-1,4-glucosidic linkages of glycogen in the lysosome. Mutations in GAA result in lysosomal enlargement due to glycogen accumulation, especially in cardiac and skeletal muscle.2 There are more than 100 different disease-causing GAA mutations identified in Pompe patients affecting enzyme expression, conformation, and activity.4 As in other LSDs, many of the mutant proteins retain residual enzyme activity in vitro but are unable to function because of impaired translocation from the ER to the lysosome. Consequently, mutant enzyme accumulates in the ER, is ubiquinated and will eventually undergo ERAD. Currently, the only FDA-approved treatment for children with this disease is ERT with recombinant human GAA (alglucosidase alfa), a recombinant human GAA produced in Chinese hamster ovary cells.5 Although recombinant human GAA (alglucosidase alfa) is proven to be clinically efficacious, treatment is not optimal. Many patients test positive for IgG antibodies to GAA which reduces the clinical utility,6 its intravenous administration is inconvenient, the cost can be over $300,000/year and adverse side effects can occur.7 This reinforces the need for developing alternative treatments for Pompe disease.

Protein translocation from ER to the site of action is a dynamic process involving distinct transporters that interact with low energy conformations of the protein, a thermodynamically driven process and kinetically accelerated by ER chaperones.8 Treatment with appropriate small-molecule chaperones could kinetically accelerate the protein folding process and promote translocation of mutant enzyme.9 For GAA, improving trafficking of the mutant protein between the ER and the lysosome by small molecule chaperone treatment might reduce glycogen storage and lysosome size.10 Iminosugars are well-known small molecule inhibitors of glycosidases11 that bind to the active site of the enzyme, mimicking the transition state of the glycolytic hydrolysis (Figure 1).12 This accelerates the folding process, and therefore iminosugar inhibitors have been proposed for the treatment of various LSDs.13 Although the chaperone activity of iminosugars is established, their use has several pitfalls. They exhibit poor selectivity among several glycosidases and need to be actively transport and therefore differences in bioavailability and body distribution among patients must be considered. Additionally due to their inhibitory activity the therapeutic window between translocation and enzyme function efficacy is small, and pharmacokinetics must be taken into consideration for modulation of the concentration at the site of action. Currently all small-molecule GAA chaperones reported in the literature are iminosugar inhibitors with 1-deoxynojirimycin (DNJ) being at the moment evaluated in a phase II clinical trial as a therapy for Pompe disease by Amicus Therapeutics Inc.14 Other than DNJ and NB-DNJ, no other reported inhibitors have been shown to have GAA chaperone capacity or utility in the treatment of Pompe disease.10

Figure 1.

Known iminosugars as inhibitors of alpha glucosidase.

Our group has developed several new screening methodologies to identify novel non-iminosugar series impacting enzymatic activity in LSD assays. We have focused on testing enzymes in a context as native as possible, including measuring the hydrolytic capacity of GAA in tissue homogenate.15 Many isolated glucosidases require allosteric activation to be functional,16 so we attempted to avoid using purified enzyme preparations, which depend upon the use of detergents to induce the active conformation and catalysis the activity of the enzyme. While it is common to find compounds that can inhibit isolated enzymes, these molecules are often inactive in cellular lysates. This is likely due to conformational differences between detergent-induced enzymatic systems and the physiological enzyme in cells, or problems with non-specific protein binding. Another limitation of reconstituted assays is the inability to detect enzyme activators, presumably because the detergent used in reconstituted assays over-activates the enzyme in a non-physiological way. One way to overcome these problems is to screen the enzyme directly from tissue homogenate using a probe specific for GAA activity, such as 4-methylumbelliferyl α-D-glucopyranoside.15 Upon hydrolysis, the blue fluorescent dye 4-methylumbelliferone is liberated, producing a fluorescent emission at 440 nm when excited at 370 nm. To control for auto-fluorescence, we also used a second substrate, resorufin α-D-glucopyranoside, which liberates the red dye resorufin at an emission wavelength of 590 nm when excited at 530 nm (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Hydrolytic reactions of the red and blue dyes.

In this study, we present the first non-iminosugar inhibitor chaperone series for GAA identified screening a novel method using tissue homogenate instead of purified enzyme preparations. This series inhibited GAA activity in both tissue homogenate and purified enzyme assays and showed translocation capacity to the lysosomal compartment in wild type and Pompe fibroblasts in a cell-based immunostaining assay.17 This promising series merits further evaluation as a potential new therapy for Pompe disease.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Hit from qHTS

244,319 compounds from the NIH Molecular Libraries-Small Molecule Repository (ML-SMR) were screened.18 The Z’ across the entire screen was 0.82 ± 0.04. Only one non-iminosugar inhibitor series, represented by compound 1, was identified based on selectivity against related enzymes including alpha galactosidase and glucocerebrosidase (data in supporting information). In addition, compound 1 displayed similar activity in both purified GAA and tissue homogenate assays, and it was not auto-fluorescent as determined by spectral profiling (Figure 3). The inhibitory activity of compound 1 was further evaluated using purified enzyme with its native substrate, glycogen. Glycogen from bovine liver was used as the substrate and recombinant human GAA as the enzyme preparation. Upon hydrolysis of the substrate, the glucose product could be detected using the Amplex Red Glucose Oxidase assay kit, and the product of this reaction was detected in a fluorescence plate reader. Compound 1 had a potency of 330 nM in this assay (data not shown), consistent with its activity in the primary screen using pro-fluorescent substrates.

Figure 3.

(A) Chemical structure of compound 1 identified from qHTS. (B) The GAA inhibitory activity of compound 1 as demonstrated by the hydrolysis of red and blue substrates using isolated GAA enzyme or tissue homogenates.

In addition to the previously described secondary assays, we tested the ability of compound 1 to protect GAA activity upon exposure to thermal defunctionalization conditions (Figure 4). Briefly, hydrolytic enzymes lose their catalytic activity over time when exposed to elevated temperatures below their melting point due to progressive denaturation and/or aggregation of the protein from solution. Incubating GAA at 66 °C for 60 minutes reduces the enzyme activity by about 75%. Small molecules with the capacity to bind and stabilize the enzyme are expected to prevent this loss of activity. Moreover, compounds able to prevent thermal destabilization usually also promote proper cellular folding and translocation, and therefore can be good chaperones. Figure 4 clearly demonstrates that compound 1 can thermo-stabilize GAA.

Figure 4.

Thermostabilization of GAA functional activity. Time indicates length of incubation at 66 °C. Ratio is the ratio of enzymatic activity after incubation at 66 °C compared to room temperature incubation. Black: DMSO (duplicated); Red: DNJ (2.5 μM); Green: qHTS sample of compound 1 (50 μM); Blue: re-synthesized compound 1 (50 μM).

Chemistry and SAR Studies

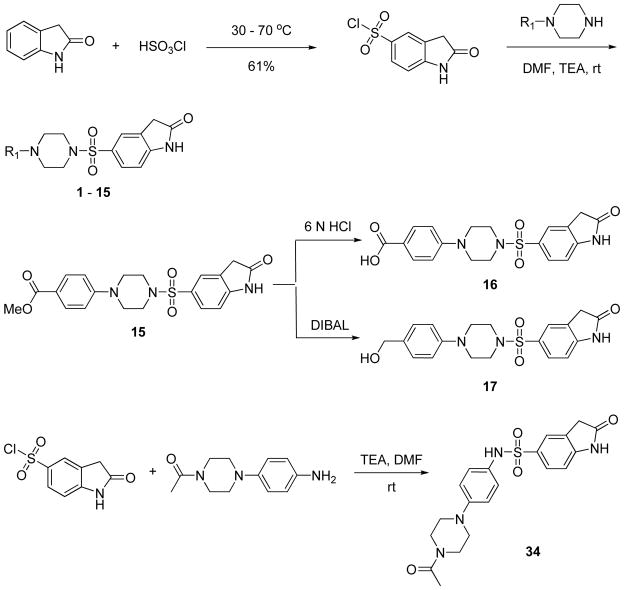

These data encouraged us to embark on structural modifications to provide a better understanding of SAR for this series. Schemes 1 and 2 showed the general methodology used for the synthesis of analogs with modifications in several regions of the molecule. Direct chlorosulfonylation of 2-indolinone at the 5-position,19 followed by piperazine or substituted aniline displacements, yielded analogs 1–15 and 34 with modifications on the aromatic ring attached to the piperazine moiety. Analog 15 with para-methyl ester substituent was readily converted to the corresponding carboxylic acid or methyl alcohol analogs 16 and 17 via acidic hydrolysis or DIBAL reduction. Alternatively, reaction of 1-(4-(piperazin-1-yl)phenyl)ethanone with a variety of sulfonyl chlorides in the presence of a suitable base such as triethylamine gave analogs with modifications at the indolinone ring (analogs 18–31). Furthermore, reaction of 1-(4-(piperazin-1-yl)phenyl)ethanone with carboxylic acid under EDC coupling conditions resulted in analogs 32 and 33 with replacement of sulfonamide moiety with a carbonamide (Scheme 2).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of analogs with modifications of phenylpiperazine moiety of the molecule.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of analogs with modifications of indolinone ring or sulfonamide portion of the molecule.

Each synthesized analog was assayed for GAA inhibition using the tissue homogenate with two different pro-fluorescent substrates, a blue shifted dye substrate that was used in the primary screen and a red shifted dye substrate. The inhibitory activity of the analogs was consistent in assays with both the blue and red-shifted dye substrates. Tables 1 to 3 demonstrate the SAR of synthesized analogs with modifications at three areas of the hit compound 1. Table 1 shows that a broad range of substituents were tolerated within the aromatic ring attached to the piperazine portion of the molecule, including para-hydroxyl (analog 5, IC50 = 1.88 μM), para-cyano (analog 7, IC50 = 2.91 μM), para-nitro (analog 8, IC50 = 3.66 μM), para-formaldehyde (analog 14, IC50 = 3.66 μM) and para-carboxylic acid (analog 16, IC50 = 1.30 μM) functional groups. However, para-methoxy, para-methyl ester and para-methyl alcohol derivatives showed a 25–50 fold loss of activity (analog 4, IC50 = 23.69 μM; analog 15, IC50 = 25.90 μM; analog 17, IC50 = 12.98 μM). Other functional groups, like halo (analogs 9–11), methyl (analog 6) and trifluoromethyl (analogs 12 and 13), were either inactive or had much less activity. Surprisingly, elimination of the phenyl ring, while keeping the methylketone moiety, resulted in derivative 3 with decent activity (IC50 = 11.87 μM), while further elimination of the methylketone group gave an inactive analog 2. These data indicates that the electronic nature of phenyl substituents has minor effect on the inhibitory activity, and that an oxygen or nitrogen at the para-position of the phenyl group might be involved in hydrogen bonding interactions enhancing activity.

Table 1.

GAA inhibitory activity of analogs with modifications of the aromatic ring attached to piperazine moiety.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| # | R1 | IC50 (μM) Blue Dye | IC50 (μM) Red Dye |

| 1 |

|

0.75 | 0.94 |

| 2 | H | inactive | inactive |

| 3 |

|

11.87 | 14.94 |

| 4 |

|

23.69 | 18.82 |

| 5 |

|

1.88 | 2.37 |

| 6 |

|

inactive | inactive |

| 7 |

|

2.91 | 3.26 |

| 8 |

|

3.66 | 3.26 |

| 9 |

|

inactive | inactive |

| 10 |

|

94.31 | 94.31 |

| 11 |

|

inactive | inactive |

| 12 |

|

inactive | inactive |

| 13 |

|

14.94 | 14.94 |

| 14 |

|

3.66 | 4.11 |

| 15 |

|

25.90 | 36.61 |

| 16 |

|

1.30 | 1.46 |

| 17 |

|

12.98 | 12.98 |

Table 3.

GAA inhibitory activity of analogs with modifications of sulfonamide and piperazine moieties.

| # | Structure | IC50 (μM) Blue Dye | IC50 (μM) Red Dye |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

0.75 | 0.94 |

| 32 |

|

inactive | inactive |

| 33 |

|

inactive | inactive |

| 34 |

|

inactive | inactive |

The SAR for the indolinone group was found to be very narrow (Table 2). Most modifications such as the introduction of more heteroatoms (analogs 18–21, 24, 31), increasing the size of the aliphatic portion of the indolin-2-one (analogs 25 and 26), or elimination of the aliphatic ring to obtain the acetamide derivatives (analogs 27–30) all yielded inactive compounds. The only modification on this part of the molecule that did not have significant impact on activity was the introduction of a chlorine substituent on the 6-position of the indolinone ring (analog 22, IC50 = 1.63 μM). The 3,3-dichloro substituted indolinone analog (23, IC50 = 32.61 μM) was also active, but much less potent.

Table 2.

GAA inhibitory activity of analogs with modifications of the indolinone ring.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| # | R1 | IC50 (μM) Blue Dye | IC50 (μM) Red Dye |

| 1 |

|

0.75 | 0.94 |

| 18 |

|

inactive | inactive |

| 19 |

|

inactive | inactive |

| 20 |

|

inactive | inactive |

| 21 |

|

inactive | inactive |

| 22 |

|

1.63 | 1.63 |

| 23 |

|

32.61 | 41.05 |

| 24 |

|

inactive | inactive |

| 25 |

|

inactive | inactive |

| 26 |

|

inactive | inactive |

| 27 |

|

inactive | inactive |

| 28 |

|

inactive | inactive |

| 29 |

|

inactive | inactive |

| 30 |

|

inactive | inactive |

| 31 |

|

inactive | inactive |

Table 3 demonstrates the effect of replacing the sulfonamide with a carbonamide (analogs 32 and 33) or a reversed phenyl and piperazine ring analog (34). All three analogs were found to be inactive. Therefore, the sulfonamide moiety also contributed significantly to the inhibitory activity of this chemical scaffold.

Biological Evaluation

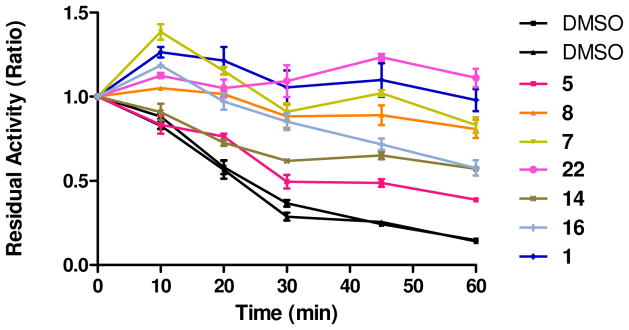

With the SAR assessment established for this scaffold, we evaluated the ability of selected analogs with reasonable potency to stabilize GAA against thermal defunctionalization. As shown in Figure 5, in the presence of tested GAA inhibitors, GAA was able to maintain its function compared to DMSO control. The stabilization observed correlated directly with the inhibitory activity of the compounds in the inhibition assay. In other words, the best inhibitors were the best stabilizers; importantly, analog 22 showed a strong ability to stabilize GAA against thermal denaturation, similar to the hit compound 1. These data demonstrated that these inhibitors could stabilize the preferred 3 dimensional conformation of GAA, validating their potential value as small-molecule chaperones.

Figure 5.

Capacity of inhibitors at 50 μM to maintain the function of GAA after incubation at 66 °C for 60 minutes.

Another way to test the capacity of a chemical series to stabilize a protein is to measure the impact of the compounds on the melting temperature (Tm) of the protein. For some chemical series, there is a direct correlation between the binding affinities of the compounds toward a protein and their capacity to increase the protein’s Tm.20 Analogs 1 and 22 demonstrated a concentration dependent ability to raise the Tm of GAA (Figure 6A). To further evaluate the binding interaction between these two analogs and GAA, we also measured the corresponding binding affinity (Kd) by microscale thermophoresis (MST).21 A direct interaction between small molecules and GAA was indeed observed for both analogs 1 and 22 (Figure 6B). Due to solubility limits, concentrations at above 250 μM could not be tested (thus saturation binding could not be determined for analog 22). Nevertheless, an apparent dissociation constant (Kd) for analogs 1 and 22 was observed to be in a range of 20–60 μM, with analog 1 showing a stronger binding than analog 22. These calculated Kd’s are 20 to 40 times higher that their reported IC50’s possibly due to differences in affinity as a consequence of labeling the enzyme and the impact in enzymatic conformation and in compound solubility of isolated-tissue homogenated conditions.

Figure 6.

(A). ΔTm versus concentrations for analogs 1 and 22. (B). Microscale thermophoresis study of analogs 1 and 22 with GAA.

The encouraging results from the GAA thermo-stabilization and direct binding experiments led us to explore whether this chemical series had an impact on GAA translocation. Most LSDs are biochemically diagnosed by measuring the specific activity of the hydrolase on patient cell samples. However, Pompe-associated glycogen accumulation primarily impacts cardiac and skeletal muscle and these tissues are often not available. Therefore, in many LSDs, including Pompe disease, the enzyme activity is analyzed on skin fibroblasts. Thus, we decided to evaluate our inhibitors in fibroblasts. In contrast to other LSDs, there is no common mutation in Pompe disease, therefore we initially chose wild type human fibroblasts to evaluate the chaperone and translocation capacity of analogs 1 and 22. First we tested the specificity of the mouse monoclonal anti-GAA antibody. On western blot, the antibody recognized the GAA protein (kDa) in protein lysate from human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells electroporated with a pCMV6XL6 plasmid containing the GAA cDNA (Acc No. NM_000152.2); non-electroporated HEK cells and wild type fibroblast protein lysates (Figure 7A) did not show a GAA specific signal. However, wild type fibroblasts express low levels of GAA. Next, we performed a cell-based translocation assay for GAA. In DMSO-treated primary wild type fibroblasts, GAA staining was observed in about 15 % of the cells, and the GAA stain (green) co-localized with the lysosomal marker cathepsin D (red) (Figure 7B, a). Wild type fibroblasts stained with secondary antibodies Alexa-488 and Alexa-555 showed no signal at the same laser settings (Figure 7B, b), indicating that the green signal from the GAA antibody was specific and not due Alexa-488 secondary antibody background. It should also be noted that GAA staining and translocation to lysosomes in fibroblasts significantly decreased with increasing cell passage number; wild type fibroblast with passage number 7 showed GAA staining in lysosomes in about 15 % of the cells, while passage 8 cells showed translocation in 10 % of the cells (data not shown). It is known that inhibitory chaperones have a small therapeutic window in which the molecule displays translocation without complete elimination of the enzymatic activity. For this reason good chaperone molecules should be weak inhibitors, allowing its displacement in the lysosome by the natural substrate. In vivo, this is resolved by titrating the optimal dose for maximal activity. In cell based assays, this is addressed by varying the compound concentration and length of exposure.

Figure 7.

Evaluation of compound 22 in GAA translocation assays using wild type and Pompe fibroblasts. (A) Western blot analysis of protein extracts from HEK cells over-expressing GAA (lane 1), HEK cells (lane 2) and wild type primary fibroblasts (lane 3). Tubulin was used as a loading control. (B, a) DMSO-treated Primary wild type fibroblasts. (B, b) DMSO-treated primary wild type fibroblasts stained with mouse Alexa-488 and goat Alexa-555(red) as a negative staining control. (B, c, d) Primary wild type fibroblasts treated with 15 μM (c) and 5 μM (d) of compound 22 for 6 days. (C, a) DMSO-treated primary Pompe fibroblasts. (C, b) Pompe fibroblasts (F2845) treated with 5 μM of compound 22 for 5 days. All stainings were performed with the anti-GAA mouse monoclonal antibody (green) and the anti-Cathepsin D goat polyclonal antibody (red); a DAPI stain was performed to visualize the nucleus (blue). Scale bar = 20 μm (B) and 50 μm (C).

Compound 1 was toxic for both wild type and Pompe fibroblasts (passage number 7) at 10, 15, and 20 μM after a 6-day treatment, suggesting that this molecule has too much inhibitory capacity, resulting in total suppression of enzyme activity. Moreover, 6-day ablation of GAA activity in fibroblasts induces cell death. After a 5-day of treatment, both wild type cells and Pompe fibroblast were viable but did not show an increase of GAA translocation upon exposure to 1 or 5 μM of compound 1, indicating that this compound might have a poor therapeutic window or that our GAA antibody does not good enough sensibility to detect low changes in this enzyme. In contrast, a 6-day treatment of wild type fibroblasts (passage number 7) with 15 μM (Figure 7B, c) or 5 μM (Figure 7B, d) of compound 22 significantly up- regulated the translocation of GAA to the lysosomes. About 40 % of the cells showed translocation of GAA with treatment at 15 μM concentration and 30 % with 5 μM. Pompe fibroblasts treated with DMSO showed no GAA signal (green) in lysosomes (Figure 7C, a). Six days of treatment with compound 22 in Pompe fibroblasts resulted in cell toxicity, probably due to excessive inhibition of the enzyme. Reducing the time of exposure provided better results. Thus, a 5-day treatment with 5 μM of compound 22 showed translocation in all three Pompe cell lines (Figure 7C, b; data only shown for the F2845 Pompe cell line) while treatment with 1 μM did not induce translocation, indicating that analog 22 is able to increase the translocation of GAA in both wild type and Pompe cell lines and showing that this chemical series has potential as a GAA chaperone for the treatment of Pompe disease. It should be noted that the concentration necessary for reasonable translocation in vivo could be considerably lower due to the high expression of GAA in affected tissues.

Last, we also measure the elevation of GAA specific activity upon treatment. Figure 8 discloses that upon five days of treatment, inhibitors 1 and 22 are able to increase GAA activity of wt and one of our mutant cell lines, confirming the results observed in our translocation experiment. Importantly, increments in activity can be observed at lower concentrations of their described IC50’s indicating a potentially good therapeutic window.

Figure 8.

Relative inhibition of GAA in WT (A) and Pompe F2845 fibroblasts (B) in a whole cell assay with treatment of compound 22 and compound 1 at pH 4 with no wash-out and after 18 and 40 hours wash out. Data points have been normalized to GAA activity in vehicle treated cells (100%)

In vitro ADME Properties

Five selected analogs with IC50 less than 3.0 μM in the GAA inhibitory assay using blue dye were profiled for PBS aqueous solubility, mouse liver microsomal stability and cell permeability in Caco-2 cells (Table 4). The aqueous solubility of the hit compound 1 in PBS buffer was 10 fold above its IC50 value. The solubility was significantly increased for analogs with polar functionalities, such as hydroxyl or carboxylic acid groups. Interestingly, the introduction of a chlorine atom at the 6-position of indolinone moiety also enhanced its aqueous buffer solubility. The microsomal stability tests disclosed that all five analogs showed excellent metabolic stability in mouse liver microsomes. In addition, this metabolic transformation was NADPH-dependent (data not shown), indicating that the major metabolic process occurs through cytochrome P450-dependent oxidation. Moreover, the data in Table 5 indicates that hit compound 1 had very good cell permeability, with reasonable efflux (ratio = 1.9, [B3A/A3B]). The chloro analog 22 has even better permeability with a reduced efflux ratio (0.57). As expected, the carboxylic acid analog 16 displayed very poor cell permeability. Overall, analog 22 demonstrated improved aqueous solubility, excellent microsomal stability, and cell permeability in addition to its capacity of increasing GAA translocation and activity in both wild type and Pompe cells. Therefore, analog 22 is a promising lead candidate for further development for the treatment of Pompe disease.

Table 4.

ADME profile of 5 selected analogs with IC50 less than 3.0 μM in the GAA inhibitory assay using blue dye.

| # | Structure | IC50 (μM) Blue Dye | PBS aqueous solubility (μM) | Mouse liver microsome T1/2 (minute) | Caco-2 Permeability mean Papp A → B (10−6 cm s−1) | Caco-2 Permeability mean Papp B → A (10−6 cm s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

0.75 | 7.9 | >60 | 14.6 | 27.1 |

| 5 |

|

1.88 | 37.3 | >60 | 17.8 | 19.5 |

| 7 |

|

2.91 | 14.9 | 57 | N/A | N/A |

| 16 |

|

1.30 | >150 | >60 | 0.60 | 0.20 |

| 22 |

|

1.63 | 20.8 | >60 | 54.30 | 30.90 |

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we present the first non-iminosugar GAA chaperone series identified from a qHTS campaign. This series of compounds inhibit GAA activity in both tissue homogenate and purified enzyme assays using native or artificial substrates. In addition, these inhibitors are highly selective against the related lysosomal hydrolases alpha galactosidase and glucocerebrosidase. SAR studies produced several optimized compounds that are able to stabilize GAA in thermo-functional and thermal denaturation assays. Furthermore, MST studies display that these molecules are indeed binders of GAA with their apparent Kds tracking well with their inhibitory activities. Improved compounds display good physical and ADME properties while maintaining GAA inhibitory activity. Importantly optimized analog 22 showed an appropriate balance between inhibitory and translocation capacity in both wild type and Pompe cells, making it a promising lead for further pharmacological development.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Chemistry Methods

All air or moisture sensitive reactions were performed under positive pressure of nitrogen with oven-dried glassware. Anhydrous solvents such as dichloromethane, N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), acetonitrile, methanol and triethylamine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Preparative purification was performed on a Waters semi-preparative HPLC system (Waters Corp., Milford, MA). The column used was a Phenomenex Luna C18 (5 micron, 30 × 75 mm; Phenomenex, Inc., Torrance, CA) at a flow rate of 45.0 mL/min. The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile and water (each containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid). A gradient of 10% to 50% acetonitrile over 8 minutes was used during the purification. Fraction collection was triggered by UV detection at 220 nM. Analytical analysis was performed on an Agilent LC/MS (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) using a method of a 7-minute gradient of 4% to 100% acetonitrile (containing 0.025% trifluoroacetic acid) in water (containing 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid) with an 8-minute run time at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. A Phenomenex Luna C18 column (3 micron, 3 × 75 mm) was used at a temperature of 50 °C. Purity determination was performed using an Agilent diode array detector and all of the analogs tested in the biological assays have a purity of greater than 95%. Mass determination was performed using an Agilent 6130 mass spectrometer with electrospray ionization in the positive mode. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on Varian 400 MHz spectrometers (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Chemical shifts are reported in ppm with undeuterated solvent (DMSO-d6 at 2.49 ppm) as internal standard for DMSO-d6 solutions. High resolution mass spectrometry was recorded on Agilent 6210 Time-of-Flight (TOF) LC/MS system. Confirmation of molecular formula was accomplished using electrospray ionization in the positive mode with the Agilent Masshunter software (Version B.02).

General Protocol A

A solution of 1-substituted piperazine (0.216 mmol), triethylamine (0.120 mL, 0.863 mmol) in DMF (1.50 mL) was treated at room temperature with 2-oxoindoline-5-sulfonyl chloride (50.0 mg, 0.216 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. The crude mixture was filtered and purified by preparative HPLC to give the final product.

General Protocol B

A solution of 1-(4-(piperazin-1-yl)phenyl)ethanone (71.5 mg, 0.350 mmol), triethylamine (0.098 mL, 0.700 mmol) in DMF (2.00 mL) was treated at room temperature with sulfonyl chloride (0.350 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. The crude mixture was filtered and purified by preparative HPLC to give the final product.

General Protocol C

A solution of 1-(4-(piperazin-1-yl)phenyl)ethanone (71.5 mg, 0.350 mmol), triethylamine (0.098 mL, 0.700 mmol) in DMF (2.00 mL) was treated at room temperature with sulfonyl chloride (0.350 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. The mixture was poured into water and the solid fraction was crushed out. The solid fraction was filtered and dried to give the final product.

General Protocol D

A solution of 1-(4-(piperazin-1-yl)phenyl)ethanone (0.086 g, 0.420 mmol), carboxylic acid (0.350 mmol) in DMF (2.00 mL) was treated at room temperature with EDC (0.067 g, 0.350 mmol) and DMAP (0.043 g, 0.350 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. The crude mixture was filtered and purified by preparative HPLC to the final product.

2-Oxoindoline-5-sulfonyl chloride

Indolin-2-one (5.00 g, 37.6 mmol) was added at 30 °C to hypochlorous sulfonic anhydride (10.2 mL, 153 mmol) in portions. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1.5 h and heated to 70 °C for 1 h. The reaction was slowly quenched with water, the light pink solid precipitation was filtered and dried to give 5.33 g (yield 61%) of product which was used in the next reaction without further purification. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.40 (s, 1 H), 7.31 – 7.46 (m, 2 H), 6.71 (dd, J=7.8, 0.6 Hz, 1 H), 3.45 (s, 2 H).

5-(4-(4-Acetylphenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)indolin-2-one (1)

A solution of 1-(4-(piperazin-1-yl)phenyl)ethanone (485 mg, 2.37 mmol), triethylamine (0.602 mL, 4.32 mmol) in DMF (10.0 mL) was treated at room temperature with 2-oxoindoline-5-sulfonyl chloride (500 mg, 2.16 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. The mixture was poured into water and the solid fraction was crushed out, filtered, and dried to give 658 mg (yield 76%) of product as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.83 (s, 1 H), 7.67 – 7.95 (m, 2 H), 7.47 – 7.71 (m, 2 H), 7.01 (d, J=8.2 Hz, 1 H), 6.88 – 6.97 (m, 2 H), 3.59 (s, 2 H), 3.38 – 3.50 (m, 4 H), 2.92 – 3.05 (m, 4 H), 2.43 (s, 3 H). LCMS RT = 4.46 min, m/z 400.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C20H22N3O4S [M+H+] 400.1326, found 400.1330.

5-(Piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)indolin-2-one (2)

A solution of piperazine (1.67 g, 19.4 mmol), triethylamine (2.71 mL, 19.4 mmol) in DMF (10.0 mL) was treated at 0 °C with 2-oxoindoline-5-sulfonyl chloride (1.50 g, 6.48 mmol) in DMF (10.0 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. DMF was removed and dichloromethane was added to precipitate out the product. The solid fraction was filtered and washed with dichloromethane to give the final product as a brown solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.89 (s, 1 H), 8.47 (br. s., 1 H), 7.51 – 7.74 (m, 2 H), 6.97 – 7.09 (m, 1 H), 3.62 (s, 2 H), 3.11 – 3.25 (m, 4 H), 2.99 – 3.11 (m, 4 H); LCMS RT = 2.66 min, m/z 282.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C12H16N3O3S [M+H+] 282.0907, found 282.0912.

5-(4-Acetylpiperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)indolin-2-one (3)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol A. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.79 (s, 1 H), 7.35 – 7.60 (m, 2 H), 6.96 (d, J=8.2 Hz, 1 H), 3.55 (s, 2 H), 3.46 (q, J=5.2 Hz, 4 H), 2.80 (ddd, J=19.8, 5.2, 4.9 Hz, 4 H), 1.89 (s, 3 H); LCMS RT = 3.36 min, m/z 346.1 [M+Na+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C14H18N3O4S [M+H+] 324.1013, found 324.1019.

5-(4-(4-Methoxyphenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)indolin-2-one (4)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol A. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.84 (s, 1 H), 7.48 – 7.71 (m, 2 H), 7.02 (d, J=8.2 Hz, 1 H), 6.70 – 6.94 (m, 4 H), 3.66 (s, 3 H), 3.61 (s, 2 H), 3.02 – 3.11 (m, 4 H), 2.91 – 3.02 (m, 4 H); LCMS RT = 4.45 min, m/z 388.1 [M+Na+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C19H22N3O4S [M+H+] 388.1326, found 388.1330.

5-(4-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)indolin-2-one (5)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol A. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.80 (s, 1 H), 8.88 (br. s., 1 H), 7.42 – 7.68 (m, 2 H), 6.98 (d, J=8.0 Hz, 1 H), 6.74 (d, J=7.6 Hz, 2 H), 6.45 – 6.67 (m, 2 H), 3.57 (s, 2 H), 2.82 – 3.09 (m, 8 H); LCMS RT = 3.49 min, m/z 374.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C18H20N3O4S [M+H+] 374.1169, found 374.1173.

5-(4-p-Tolylpiperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)indolin-2-one (6)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol A. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.82 (s, 1 H), 7.45 – 7.66 (m, 2 H), 7.00 (dd, J=8.0, 5.9 Hz, 3 H), 6.74 – 6.85 (m, 2 H), 3.59 (s, 2 H), 3.06 – 3.21 (m, 4 H), 2.89 – 3.06 (m, 4 H), 2.17 (s, 3 H); LCMS RT = 5.08 min, m/z 372.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C19H22N3O3S [M+H+] 372.1376, found 372.1380.

4-(4-(2-Oxoindolin-5-ylsulfonyl)piperazin-1-yl)benzonitrile (7)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol A. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.79 (s, 1 H), 7.40 – 7.66 (m, 4 H), 6.82 – 7.13 (m, 3 H), 3.54 (s, 2 H), 3.36 – 3.43 (m, 4 H), 2.88 – 2.97 (m, 4 H); LCMS RT = 4.89 min, m/z 383.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C19H19N4O3S [M+H+] 383.1172, found 383.1173.

5-(4-(4-Nitrophenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)indolin-2-one (8)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol A. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.79 (s, 1 H), 8.00 (d, J=9.6 Hz, 2 H), 7.47 – 7.64 (m, 2 H), 6.88 – 7.04 (m, 3 H), 3.45 – 3.68 (m, 6 H), 2.85 – 3.01 (m, 4 H); LCMS RT = 5.02 min, m/z 425.1 [M+Na+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C18H19N4O5S [M+H+] 403.1071, found 403.1071.

5-(4-(4-Fluorophenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)indolin-2-one (9)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol A. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.80 (s, 1 H), 7.41 – 7.69 (m, 2 H), 6.93 – 7.08 (m, 3 H), 6.77 – 6.92 (m, 2 H), 3.56 (s, 2 H), 3.05 – 3.16 (m, 4 H), 2.87 – 3.00 (m, 4 H); 19F NMR (376 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm −126.55 – 123.72 (m); LCMS RT = 5.15 min, m/z 376.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C18H19FN3O3S [M+H+] 376.1126, found 376.1138.

5-(4-(4-Chlorophenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)indolin-2-one (10)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol A. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.82 (s, 1 H), 7.49 – 7.74 (m, 2 H), 7.13 – 7.31 (m, 2 H), 7.01 (d, J=8.2 Hz, 1 H), 6.78 – 6.96 (m, 2 H), 3.59 (s, 2 H), 3.13 – 3.24 (m, 4 H), 2.87 – 3.03 (m, 4 H); LCMS RT = 5.57 min, m/z 392.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C18H19ClN3O3S [M+H+] 392.0830, found 392.0842.

5-(4-(4-Bromophenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)indolin-2-one (11)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol A. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.80 (s, 1 H), 7.48 – 7.72 (m, 2 H), 7.19 – 7.37 (m, 2 H), 6.98 (d, J=8.2 Hz, 1 H), 6.77 – 6.87 (m, 2 H), 3.56 (s, 2 H), 3.10 – 3.21 (m, 4 H), 2.88 – 2.98 (m, 4 H); LCMS RT = 5.67 min, m/z 436.0 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C18H19BrN3O3S [M+H+] 436.0325, found 436.0338.

5-(4-(4-(Trifluoromethyl)phenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)indolin-2-one (12)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol A. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.82 (s, 1 H), 7.52 – 7.68 (m, 2 H), 7.48 (d, J=8.6 Hz, 2 H), 6.76 – 7.13 (m, 3 H), 3.58 (s, 2 H), 3.33 – 3.42 (m, 4 H), 2.93 – 3.03 (m, 4 H); 19F NMR (376 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm −59.64 (s); LCMS RT = 5.78 min, m/z 426.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C19H19F3N3O3S [M+H+] 426.1094, found 426.1101.

5-(4-(3-(Trifluoromethyl)phenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)indolin-2-one (13)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol A. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.83 (s, 1 H), 7.50 – 7.73 (m, 2 H), 7.40 (t, J=7.9 Hz, 1 H), 7.11 – 7.22 (m, 2 H), 7.08 (d, J=8.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.01 (d, J=8.0 Hz, 1 H), 3.59 (s, 2 H), 3.25 – 3.31 (m, 4 H), 2.94 – 3.04 (m, 3 H); 19F NMR (376 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm −61.14 (s); LCMS RT = 5.78 min, m/z 426.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C19H19F3N3O3S [M+H+] 426.1094, found 426.1104.

4-(4-(2-Oxoindolin-5-ylsulfonyl)piperazin-1-yl)benzaldehyde (14)

A solution of 4-(piperazin-1-yl)benzaldehyde, TFA salt (58.0 mg, 0.139 mmol), and triethylamine (0.039 mL, 0.277 mmol) in dichloromethane (2.00 mL) was treated at room temperature with 2-oxoindoline-5-sulfonyl chloride (32.1 mg, 0.139 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred for 3 h at room temperature. The solid was filtered and dried to a yellow solid product. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.79 (s, 1 H), 9.67 (s, 1 H), 7.60 – 7.72 (m, 2 H), 7.49 – 7.61 (m, 2 H), 6.90 – 7.04 (m, 3 H), 3.55 (s, 2 H), 3.37 – 3.50 (m, 4 H), 2.85 – 2.98 (m, 4 H); LCMS RT = 4.55 min, m/z 386.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C19H20N3O4S [M+H+] 386.1169, found 386.1169.

Methyl 4-(4-(2-oxoindolin-5-ylsulfonyl)piperazin-1-yl)benzoate (15)

A solution of methyl 4-(piperazin-1-yl)benzoate (0.687 g, 3.12 mmol), triethylamine (0.870 mL, 6.24 mmol) in dichloromethane (15.0 mL) was treated at room temperature with 2-oxoindoline-5-sulfonyl chloride (0.723 g, 3.12 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. The yellow solid was filtered and dried to the final product. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.80 (s, 1 H), 7.66 – 7.82 (m, 2 H), 7.46 – 7.63 (m, 2 H), 6.79 – 7.09 (m, 3 H), 3.72 (s, 3 H), 3.55 (s, 2 H), 3.32 – 3.45 (m, 4 H), 2.85 – 3.05 (m, 4 H); LCMS RT = 5.14 min, m/z 416.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C20H22N3O5S [M+H+] 416.1275, found 416.1282.

4-(4-(2-Oxoindolin-5-ylsulfonyl)piperazin-1-yl)benzoic acid (16)

A suspension of methyl 4-(4-(2-oxoindolin-5-ylsulfonyl)piperazin-1-yl)benzoate (15) (240 mg, 0.578 mmol) in 6.0 N HCl (75.0 mL) was refluxed for 1 h. The reaction mixture was concentrated and purified by preparative HPLC to the final product. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 12.25 (br. s., 1 H), 10.80 (br. s., 1 H), 7.63 – 7.79 (m, 2 H), 7.38 – 7.63 (m, 2 H), 6.70 – 7.08 (m, 3 H), 3.56 (s, 2 H), 3.32 – 3.43 (m, 4 H), 2.84 – 3.05 (m, 4 H); LCMS RT = 4.46 min, m/z 402.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C19H20N3O5S [M+H+] 402.1118, found 402.1126.

5-(4-(4-(Hydroxymethyl)phenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)indolin-2-one (17)

DIBAL (0.325 mL, 1.0 M in THF, 0.325 mmol) was added drop wise to a solution of methyl 4-(4-(2-oxoindolin-5-ylsulfonyl)piperazin-1-yl)benzoate (15) (45.0 mg, 0.108 mmol) in THF (5.00 mL) at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 30 min. The reaction was quenched by addition of methanol, concentrated as a yellow oil which was purified by preparative HPLC to the final product. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.80 (s, 1 H), 7.48 – 7.72 (m, 2 H), 7.10 (d, J=8.8 Hz, 2 H), 6.98 (d, J=8.2 Hz, 1 H), 6.74 – 6.86 (m, 2 H), 4.32 (s, 2 H), 3.57 (s, 2 H), 3.05 – 3.22 (m, 4 H), 2.88 – 3.04 (m, 4 H); LCMS RT = 4.06 min, m/z 388.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C19H22N3O4S [M+H+] 388.1326, found 388.1330.

5-(4-(4-Acetylphenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2(3H)-one (18)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol B. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 11.15 (d, J=1.2 Hz, 1 H), 10.99 (s, 1 H), 7.59 – 7.87 (m, 2 H), 7.33 (dd, J=8.2, 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.04 – 7.22 (m, 2 H), 6.79 – 6.97 (m, 2 H), 3.33 – 3.51 (m, 4 H), 2.84 – 3.03 (m, 4 H), 2.39 (s, 3 H); LCMS RT = 4.40 min, m/z 401.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C19H21N4O4S [M+H+] 401.1278, found 401.1286.

5-(4-(4-Acetylphenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)-1,3-dimethyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2(3H)-one (19)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 7.65 – 7.78 (m, 2 H), 7.40 – 7.54 (m, 2 H), 7.34 (d, J=8.6 Hz, 1 H), 6.79 – 6.96 (m, 2 H), 3.38 – 3.44 (m, 4 H), 3.36 (s, 3 H), 3.33 (s, 3 H), 2.92 – 3.04 (m, 4 H), 2.39 (s, 3 H); LCMS RT = 5.07 min, m/z 429.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C21H25N4O4S [M+H+] 429.1591, found 429.1592.

6-(4-(4-Acetylphenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)benzo[d]oxazol-2(3H)-one (20)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 12.14 (br. s., 1 H), 7.70 – 7.78 (m, 2 H), 7.63 (d, J=1.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.53 (dd, J=8.2, 1.6 Hz, 1 H), 7.26 (d, J=8.2 Hz, 1 H), 6.85 – 6.94 (m, 2 H), 3.35 – 3.45 (m, 4 H), 2.92 – 3.03 (m, 4 H), 2.39 (s, 3 H); LCMS RT = 5.07 min, m/z 402.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C19H20N3O5S [M+H+] 402.1118, found 402.1130.

6-(4-(4-Acetylphenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)-3-methylbenzo[d]oxazol-2(3H)-one (21)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 7.71 – 7.76 (m, 2 H), 7.69 (d, J=1.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.62 (dd, J=8.3, 1.7 Hz, 1 H), 7.45 (d, J=8.0 Hz, 1 H), 6.78 – 6.95 (m, 2 H), 3.36 – 3.45 (m, 4 H), 3.33 (s, 3 H), 2.92 – 3.04 (m, 4 H), 2.39 (s, 3 H); LCMS RT = 5.22 min, m/z 416.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C20H22N3O5S [M+H+] 416.1275, found 416.1284.

5-(4-(4-Acetylphenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)-6-chloroindolin-2-one (22)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol B. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.88 (s, 1 H), 7.67 – 7.89 (m, 3 H), 6.79 – 7.08 (m, 3 H), 3.57 (s, 2 H), 3.36 – 3.46 (m, 4 H), 3.19 – 3.27 (m, 4 H), 2.43 (s, 3 H); LCMS RT = 4.92 min, m/z 434.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C20H21ClN3O4S [M+H+] 434.0936, found 434.0942.

5-(4-(4-Acetylphenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)-3,3-dichloroindolin-2-one (23)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol B. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 11.86 (s, 1 H), 7.95 (d, J=1.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.83 (dd, J=8.4, 2.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.73 – 7.80 (m, 2 H), 7.20 (d, J=8.4 Hz, 1 H), 6.90 – 6.98 (m, 2 H), 3.38 – 3.48 (m, 4 H), 2.99 – 3.08 (m, 4 H), 2.42 (s, 3 H); LCMS RT = 5.57 min, m/z 468.0 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C20H20Cl2N3O4S [M+H+] 468.0546, found 468.0547.

6-(4-(4-Acetylphenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)isobenzofuran-1(3H)-one (24)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 8.11 (dd, J=8.0, 1.6 Hz, 1 H), 8.05 (d, J=1.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.94 (dd, J=8.1, 0.7 Hz, 1 H), 7.69 – 7.77 (m, 2 H), 6.85 – 6.95 (m, 2 H), 5.48 (s, 2 H), 3.36 – 3.46 (m, 4 H), 2.99 – 3.10 (m, 4 H), 2.39 (s, 3 H); LCMS RT = 5.12 min, m/z 401.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C20H21N2O5S [M+H+] 401.1166, found 401.1177.

6-(4-(4-Acetylphenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)-3,4-dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-one (25)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.46 (s, 1 H), 7.67 – 7.79 (m, 2 H), 7.54 (d, J=2.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.51 (dd, J=8.4, 2.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.00 (d, J=8.4 Hz, 1 H), 6.86 – 6.95 (m, 2 H), 3.34 – 3.46 (m, 4 H), 2.89 – 3.03 (m, 6 H), 2.40 (s, 3 H) (2 protons were hidden under DMSO-d6 peaks); LCMS RT = 4.91 min, m/z 414.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C21H24N3O4S [M+H+] 414.1482, found 414.1491.

7-(4-(4-Acetylphenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-benzo[b]azepin-2(3H)-one (26)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 9.88 (s, 1 H), 7.70 – 7.78 (m, 2 H), 7.63 (d, J=2.3 Hz, 1 H), 7.58 (dd, J=8.3, 2.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.13 (d, J=8.2 Hz, 1 H), 6.85 – 6.95 (m, 2 H), 3.33 – 3.46 (m, 4 H), 2.93 – 3.05 (m, 4 H), 2.75 (t, J=6.8 Hz, 2 H), 2.40 (s, 3 H), 2.03 – 2.22 (m, 4 H); LCMS RT = 4.93 min, m/z 428.2 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C22H26N3O4S [M+H+] 428.1639, found 428.1644.

N-(4-(4-(4-Acetylphenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)phenyl)acetamide (27)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.34 (s, 1 H), 7.76 – 7.82 (m, 2 H), 7.71 – 7.76 (m, 2 H), 7.61 – 7.69 (m, 2 H), 6.87 – 6.94 (m, 2 H), 3.35 – 3.43 (m, 4 H), 2.90 – 2.99 (m, 4 H), 2.40 (s, 3 H), 2.04 (s, 3 H); LCMS RT = 5.04 min, m/z 402.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C20H24N3O4S [M+H+] 402.1482, found 402.1485.

1-(4-(4-(4-Acetylphenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)phenyl)pyrrolidin-2-one (28)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 7.87 – 7.97 (m, 2 H), 7.67 – 7.77 (m, 4 H), 6.83 – 6.95 (m, 2 H), 3.84 (t, J=7.0 Hz, 2 H), 3.36 – 3.46 (m, 4 H), 2.89 – 2.99 (m, 4 H), 2.50 (t, J=8.1 Hz, 2 H), 2.39 (s, 3 H), 2.03 (ddd, J=15.1, 7.5, 7.3 Hz, 2 H); LCMS RT = 5.22 min, m/z 428.2 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C22H26N3O4S [M+H+] 428.1639, found 428.1644.

1-(4-(4-(1-Acetyl-2-methylindolin-5-ylsulfonyl)piperazin-1-yl)phenyl)ethanone (29)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 8.11 (br. s., 1 H), 7.67 – 7.78 (m, 2 H), 7.47 – 7.63 (m, 2 H), 6.78 – 6.96 (m, 2 H), 4.51 – 4.76 (m, 1 H), 3.32 – 3.46 (m, 5 H), 2.88 – 3.03 (m, 4 H), 2.73 (d, J=16.8 Hz, 1 H), 2.40 (s, 3 H), 2.23 (s, 3 H), 1.18 (d, J=6.5 Hz, 3 H); LCMS RT = 5.38 min, m/z 442.2 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C23H28N3O4S [M+H+] 442.1795, found 442.1797.

1-(4-(4-(1-Acetyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinolin-6-ylsulfonyl)piperazin-1-yl)phenyl)ethanone (30)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 7.80 – 7.87 (m, 1 H), 7.70 – 7.77 (m, 2 H), 7.52 (d, J=2.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.48 (dd, J=8.6, 2.3 Hz, 1 H), 6.86 – 6.95 (m, 2 H), 3.62 – 3.72 (m, 2 H), 3.36 – 3.44 (m, 4 H), 2.92 – 3.01 (m, 4 H), 2.78 (t, J=6.5 Hz, 2 H), 2.40 (s, 3 H), 2.18 (s, 3 H), 1.85 (dq, J=6.6, 6.3 Hz, 2 H); LCMS RT = 5.27 min, m/z 442.2 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C23H28N3O4S [M+H+] 442.1795, found 442.1807.

7-(4-(4-acetylphenyl)piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)-2H-benzo[b][1,4]oxazin-3(4H)-one (31)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.88 (s, 1 H), 7.71 – 7.78 (m, 2 H), 7.25 – 7.30 (m, 1 H), 7.23 – 7.25 (m, 1 H), 7.13 (d, J=8.4 Hz, 1 H), 6.85 – 6.94 (m, 2 H), 4.67 (s, 2 H), 3.37 – 3.46 (m, 4 H), 2.91 – 3.00 (m, 4 H), 2.40 (s, 3 H); LCMS RT = 4.94 min, m/z 416.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C20H22N3O5S [M+H+] 416.1275, found 416.1281.

5-(4-(4-Acetylphenyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)indolin-2-one (32)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol D. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.55 (s, 1 H), 7.70 – 7.88 (m, 2 H), 7.23 – 7.40 (m, 2 H), 6.98 (d, J=9.2 Hz, 2 H), 6.85 (d, J=8.0 Hz, 1 H), 3.63 (br. s., 4 H), 3.51 (s, 2 H), 3.37 – 3.46 (m, 4 H), 2.45 (s, 3 H); LCMS RT = 4.14 min, m/z 364.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C21H22N3O3S [M+H+] 364.1656, found 364.1661.

6-(4-(4-Acetylphenyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)-3,4-dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-one (33)

The title compound was prepared according to general protocol D. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.22 (s, 1 H), 7.69 – 7.88 (m, 2 H), 7.26 (d, J=1.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.22 (dd, J=8.0, 2.0 Hz, 1 H), 6.90 – 6.98 (m, 2 H), 6.86 (d, J=8.2 Hz, 1 H), 3.60 (br. s., 4 H), 3.51 (br. s., 4 H), 2.88 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 2 H), 2.44 – 2.45 (m, 1 H), 2.40 – 2.43 (m, 4 H); LCMS RT = 4.30 min, m/z 378.2 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C22H24N3O3S [M+H+] 378.1812, found 378.1815.

N-(4-(4-Acetylpiperazin-1-yl)phenyl)-2-oxoindoline-5-sulfonamide (34)

A solution of 1-(4-(4-aminophenyl)piperazin-1-yl)ethanone (76.0 mg, 0.345 mmol), triethylamine (0.096 mL, 0.691 mmol) in DMF (3.00 mL) was treated at 0 °C with 2-oxoindoline-5-sulfonyl chloride (80.0 mg, 0.345 mmol). The reaction mixture was warmed to room temperature and stirred overnight. The crude mixture was filtered and purified by preparative HPLC to give the final product. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 10.72 (s, 1 H), 9.70 (s, 1 H), 7.51 (dd, J=4.0, 2.6 Hz, 2 H), 6.89 – 6.96 (m, 2 H), 6.84 – 6.89 (m, 1 H), 6.77 – 6.84 (m, 2 H), 3.53 (s, 6 H), 2.93 – 3.08 (m, 4 H), 2.00 (s, 3 H); LCMS RT = 3.55 min, m/z 415.1 [M+H+]; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd. for C20H23N4O4S [M+H+] 415.1435, found 415.1448.

General Biological Experiments

The recombinant wild type enzyme Myozyme® (alglucosidase alfa), clinically approved for ERT, was obtained from Genzyme Corporation (Cambridge, MA). Patients’ spleens were obtained from splenectomies with informed consent under an NIH-IRB approved clinical protocol # 86HG0096. Control spleens were obtained under the same NIH protocol #. 4-methylumbelliferyl-α-D-glucopyranoside (4MU-α-glc), resorufin α-D-glucopyranoside (res-α-glc), sodium taurocholate, and the buffer components were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). 1-Deoxynojirimycin (DNJ) was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Minneapolis, MN). The human spleen tissue was homogenized using a food blender at the maximal speed for 5 minutes, followed by 10 passes in a motor-driven 50 mL glass-Teflon homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 1000×g for 10 minutes. The supernatant was then filtered using a 40 μm filter and aliquots of resultant spleen homogenate were frozen at −80 °C until use. The assay buffer was composed of 50 mM citric acid titrated with K2PO4 to make different pH solutions, and 0.01% Tween-20. The spleen homogenate assays used buffer at pH = 5, assays with recombinant wild type enzyme used buffer at pH = 5.9.

Enzyme Assay in 1,536-Well Plate Format

In black 1,536-well plates, a BioRAPTR FRD™ Microfluidic Workstation (Beckman Coulter, Inc. Fullerton, CA) was used to dispense 2 μL of the enzyme solutions into 1,536-well plates, and an automated pin-tool station (Kalypsys, San Diego, CA) was used to transfer 23 nL/well of compound to the assay plate. After 5 minutes incubation at room temperature, the enzyme reaction was initiated by the addition of 2 μL/well substrate. After 45 minutes incubation at 37 °C, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 2 μL/well stop solution. The fluorescence was then measured in the Viewlux, a CCD-based plate reader (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA), with a 365 nm excitation and 440 nm emission for the blue substrate, and 573 nm excitation and 610 nm emission for the red substrate. 27 μg/well of spleen homogenate was used as the enzyme solution. The final concentrations of the blue substrate and red substrate were 1 μM and 15 μM, respectively.

Thermo-denaturation Experiment

This assay measures the effect of compounds on the melting temperature (Tm) of the recombinant wild type GAA. The protocol was developed based on a previously reported general guideline.22 A mixture of GAA and SYPRO Orange (5000× stock concentration, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was delivered to a 384-well full-skirted white polypropylene plate (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) with a final concentration of 1 μM and 5×, respectively. GAA and SYPRO Orange were diluted in 50 mM citrate acid buffer at pH = 5.0 supplemented with 100 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl and 1 mM MgCl2. A 6-point DMSO dilution series was made separately in a 384-well polypropylene plate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Hudson, NH) for all analogs, whose final concentrations ranged from 0.82 – 200 μM. Half a microliter of each dilution point of each compound was transferred to the aforementioned GAA-SYPRO Orange mixture, with a final DMSO concentration of 2%. DMSO alone was also transferred to the assay plate for each dilution series as a control sample. The plate was immediately centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 10 second and subsequently sealed with sealing foils (Roche Applied Science). The plate was then heated using a LightCycler® 480 Instrument II (Roche Applied Science) from 20 to 95 °C at a ramping rate of 4.8 °C/s. SYPRO Orange fluorescence was monitored by a CCD camera using excitation and emission wavelengths of 498 and 580 nm, respectively. Tm was calculated through the LightCycler® 480 II Software.

Microscale Thermophoresis

GAA was labeled with a fluorescent dye NT-495 (NanoTemper Technologies) and the final concentration of the protein applied in equilibrium binding experiments was ~ 50 nM. A 16-point titration series of selected compounds was prepared in DMSO and was further transferred toprotein solutions in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, pH = 7.5. The final concentrations of the compounds ranged from 250 μM to 7.63 nM, with the DMSO final concentration controlled at 2.5%. Samples were filled into Monolith NT™ standard treated capillaries (NanoTemper Technologies) after a room temperature incubation of 15 minutes. Capillary scan was performed on a NanoTemper Monolith NT.115 instrument, and thermophoresis was successively measured in each capillary. Measurement took place at room temperature with an 80% IR laser power, and the blue LED power set at 100%. Specifically, a laser-on time of 30 seconds and a laser-off time of 5 seconds were applied at the indicated IR-laser power. Data normalization and curve fitting were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.

Cells, Plasmids and Electroporation

Wild type fibroblasts and HEK cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Electroporation of the HEK cells with pCMV6XL6-GAA plasmid (Origene, Rockville, MD) was performed in a Nucleofector electroporator, according to the manufacturer’s guidelines (Lonza, Walkersville, MD). Briefly, a mixture of 100 μL Nucleofector solution and 2 μg plasmid DNA was added to approximately 700,000 HEK cells, electroporation was performed with the Q_001 Nucleofector program. For our translocation experiments besides wt we used three Pompe fibroblast cell lines isolated from patients and with low passage number with the following mutations: Cell line F3248 heterozygous for: p.Y455C/p.G638W Cell line F0833 heterozygous for: p.L169P/p.D489N Cell line F2845 has a splice site mutation in one allele: c.IVS1-13T>G and p.G638W on the other one.

Western Blot Analysis

Equivalent amounts of total protein, as determined by BCA assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL), from HEK cells or fibroblasts were loaded onto 4–12 % Tris-Glycine gels. After blotting (iBlot PVDF, Invitrogen, CA), the PVDF membrane was blocked in Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% Tween-20 (Sigma) and 5% fat-free milk for 1 hour at room temperature. The blocked membrane was probed with a mouse monoclonal antibody against human GAA (Abnova, Walnut, CA), followed by incubation with HRP-labeled secondary anti-mouse antibody (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). The antigen-antibody complexes were detected with an Enhanced Chemiluminescence (ECL) kit (Amersham Biosciences). Alpha-Tubulin was used as the internal control for normalization.

Immunocytochemistry and Laser Scanning Confocal Microscopy

Wild type primary dermal human fibroblasts (ATCC) and primary Pompe fibroblasts were seeded in Lab-Tek 4 chamber slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). After chemical compound treatment for five or six days, fibroblasts were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde. The cells were permeabilized with 0.1 % Triton-X for 10 min. and blocked in PBS containing 0.1% saponin, 100 μM glycine, 0.1% BSA and 2% donkey serum followed by incubation with mouse monoclonal anti-GAA (Abnova, Walnut, CA) or goat polyclonal anti-cathepsin D (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The cells were washed and incubated with secondary donkey anti-mouse or anti-goat antibodies conjugated to ALEXA-488 or ALEXA-555, respectively (Invitrogen), washed again, and mounted in VectaShield with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Cells were imaged with a Zeiss 510 META confocal laser-scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, Microimaging Inc., Germany) using an Argon (458, 477, 488, 514 nm) 30 mW laser, a HeNe (543 nm) 1 mW laser, and a laser diode (405 nm). Images were acquired using a Plan-Apochromat 63x/1.4 Oil, a Plan NeoFluar 40X/1.3 oil DIC objective, or a Plan-Apochromat 20x/0.15. Images were taken at the same laser settings.

Specific activity measurement

GAA activity in WT and Pompe fibroblasts was measured similar to the method used by Flanagan et al., 2009. Briefly, for each cell line cells were seeded in 3 black clear flat bottom 96-well plates (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA) at 5,000 cells/well. Inhibitors (DNJ) were added (50nM to 503M), and the cells were incubated for 5 days with compounds; the media and compounds were changed on day 3. 1 plate of each cell line was assayed immediately while for 2 plates of each cell line, fibroblasts were washed with PBS and fresh medium without compounds was added (18 hour and 40 hour wash out). 30 μL of assay buffer (30mM sodium citrate, 40mM sodium phosphate dibasic, 3mM 4MUG (Sigma), 33M Acarbose (Sigma), pH 4.0) was added (no wash out) and plates were incubated for 2 hours at 37C and 30 mu;L of stop solution (1M NaOH, 1M glucine, pH 10) was added; a Victor plate reader (Perkin-Elmer) was used to measure fluorescence signal. Fluorescence counts from fibroblast assay buffer + stop solution (background counts) were subtracted from the cell samples and the relative GAA activity was calculated. Measurements were done in triplicate for each sample and the average GAA activity ±SD is reported.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank William Leister, Jim Bougie, Chris Leclair, Thomas Daniel, Heather Baker, Paul Shinn, and Danielle van Leer for assistance with compounds purification, HRMS analysis and compounds management. We also thank Ms. Allison Mandich and Ms. Mercedes Taylor for critical proofreading of the manuscript. This research was supported by the Molecular Libraries Initiative of the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research (U54MH084681) and the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- LSDs

lysosomal storage diseases

- GAA

acid alpha glucosidase

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- ERAD

endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation

- ERT

Enzyme replacement therapy

- AMDE

absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion

- BBB

Blood-Brain-Barrier

- LAMP-2

lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2

- HTS

high throughput screening

- ML-SMR

Molecular Libraries-Small Molecule Repository

- DNJ

1-deoxynojirimycin

- FDA

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- DIBAL

diisobutylaluminium hydride

- EDC

1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride

- SAR

structure-activity relationship

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- TLC

thin layer chromatography

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- DMAP

4-dimethylaminopyridine

- MST

microscale thermophoresis

Footnotes

The data from the primary screening as well as all the inhibitory curves of every final compound in all the described assays are available on line (PubChem AID’s: 1466, 2101, 2107, 2108, 2109, 2100, 2110, 2111, 2112, 2113, 2115 and 2641). Additional data of our translocation experiment and selectivity assays for compound 1 are available free of charge at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Smid BE, Aerts JMFG, Boot RG, Linthorst GE, Hollak CEM. Pharmacological small molecules for the treatment of lysosomal storage disorders. Expert Opin Invest Drugs. 2010;19:1367–1379. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2010.524205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirschhorn R, Reuser AJJ. Glycogen storage disease type II: acid α-glucosidase (acid maltase) deficiency. In: Valle D, editor. The metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease. Chapter 135 McGraw–Hill; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martiniuk F, Chen A, Mack A, Arvanitopoulos E, Chen Y, Rom WN, Codd WJ, Hanna B, Alcabes P, Raben N, Plotz P. Carrier frequency for glycogen storage disease type II in New York and estimates of affected individuals born with the disease. Am J Med Genet. 1998;79:69–72. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19980827)79:1<69::aid-ajmg16>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk; Raben N, Plotz P, Byrne BJ. Acid α-glucosidase deficiency (glycogenosis type II, Pompe disease) Curr Mol Med. 2002;2:145–166. doi: 10.2174/1566524024605789.

- 5.(a) http://www.myozyme.com/; Kishnani PS, Corzo D, Nicolino M, Byrne B, Mandel H, Hwu WL, Leslie N, Levine J, Spencer C, McDonald M, Li J, Dumontier J, Halberthal M, Chien YH, Hopkin R, Vijayaraghavan S, Gruskin D, Bartholomew D, van dPA, Clancy JP, Parini R, Morin G, Beck M, De lGGS, Jokic M, Thurberg B, Richards S, Bali D, Davison M, Worden MA, Chen YT, Wraith JE. Recombinant human acid α-glucosidase: Major clinical benefits in infantile-onset Pompe disease. Neurology. 2007;68:99–109. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000251268.41188.04.

- 6.http://www.rxlist.com/myozyme-drug.htm.

- 7.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myozyme.

- 8.Fan JQ, Ishii S. Active-site-specific chaperone therapy for Fabry disease Yin and Yang of enzyme inhibitors. FEBS J. 2007;274:4962–4971. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Hermans MMP, Van LD, Kroos MA, Beesley CE, Van dPAT, Sakuraba H, Wevers R, Kleijer W, Michelakakis H, Kirk EP, Fletcher J, Bosshard N, Basel-Vanagaite L, Besley G, Reuser AJJ. Twenty-two novel mutations in the lysosomal α-glucosidase gene (GAA) underscore the genotype-phenotype correlation in glycogen storage disease type II. Hum Mutat. 2004;23:47–56. doi: 10.1002/humu.10286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Montalvo ALE, Cariati R, Deganuto M, Guerci V, Garcia R, Ciana G, Bembi B, Pittis MG. Glycogenosis type II: identification and expression of three novel mutations in the acid α-glucosidase gene causing the infantile form of the disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2004;81:203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Reuser AJJ, Kroos M, Oude ERPJ, Tager JM. Defects in synthesis, phosphorylation, and maturation of acid α-glucosidase in glycogenosis type II. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:8336–8341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Reuser AJJ, Kroos M, Willemsen R, Swallow D, Tager JM, Galjaard H. Clinical diversity in glycogenosis type II. Biosynthesis and in situ localization of acid α-glucosidase in mutant fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:1689–1699. doi: 10.1172/JCI113008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beck M. New therapeutic options for lysosomal storage disorders: enzyme replacement, small molecules and gene therapy. Hum Genet. 2007;121:1–22. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0280-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Asano N. Glycosidase inhibitors: update and perspectives on practical use. Glycobiology. 2003;13:93R–104R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yoshimizu M, Tajima Y, Matsuzawa F, Aikawa S-i, Iwamoto K, Kobayashi T, Edmunds T, Fujishima K, Tsuji D, Itoh K, Ikekita M, Kawashima I, Sugawara K, Ohyanagi N, Suzuki T, Togawa T, Ohno K, Sakuraba H. Binding parameters and thermodynamics of the interaction of imino sugars with a recombinant human acid [alpha]-glucosidase (alglucosidase alfa): Insight into the complex formation mechanism. Clin Chim Acta. 2008;391:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan JQ. A counterintuitive approach to treat enzyme deficiencies: use of enzyme inhibitors for restoring mutant enzyme activity. Biol Chem. 2008;389:1–11. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.009.(b) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alpha-glucosidase_inhibitor

- 13.(a) Butters TD, Dwek RA, Platt FM. Therapeutic applications of imino sugars in lysosomal storage disorders. Curr Top Med Chem. 2003;3:561–574. doi: 10.2174/1568026033452483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lieberman RL, D’aquino JA, Ringe D, Petsko GA. Effects of pH and Iminosugar Pharmacological Chaperones on Lysosomal Glycosidase Structure and Stability. Biochemistry. 2009;48:4816–4827. doi: 10.1021/bi9002265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Flanagan JJ, Rossi B, Tang K, Wu X, Mascioli K, Donaudy F, Tuzzi MR, Fontana F, Cubellis MV, Porto C, Benjamin E, Lockhart DJ, Valenzano KJ, Andria G, Parenti G, Do HV. The pharmacological chaperone 1-deoxynojirimycin increases the activity and lysosomal trafficking of multiple mutant forms of acid alpha-glucosidase. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1683–1692. doi: 10.1002/humu.21121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Okumiya T, Kroos MA, Vliet LV, Takeuchi H, Van dPAT, Reuser AJJ. Chemical chaperones improve transport and enhance stability of mutant α-glucosidases in glycogen storage disease type II. Mol Genet Metab. 2007;90:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Parenti G, Zuppaldi A, Pittis MG, Tuzzi MR, Annunziata I, Meroni G, Porto C, Donaudy F, Rossi B, Rossi M, Filocamo M, Donati A, Bembi B, Ballabio A, Andria G. Pharmacological Enhancement of Mutated α-Glucosidase Activity in Fibroblasts from Patients with Pompe Disease. Mol Ther. 2007;15:508–514. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Motabar O, Shi ZD, Goldin E, Liu K, Southall N, Sidransky E, Austin CP, Griffiths GL, Zheng W. A new resorufin-based α-glucosidase assay for high-throughput screening. Anal Biochem. 2009;390:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) John M, Wendeler M, Heller M, Sandhoff K, Kessler H. Characterization of Human Saposins by NMR Spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2006;45:5206–5216. doi: 10.1021/bi051944+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zwerschke W, Mannhardt B, Massimi P, Nauenburg S, Pim D, Nickel W, Banks L, Reuser AJ, Jansen-Durr P. Allosteric activation of acid α-glucosidase by the human papillomavirus E7 protein. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9534–9541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marugan JJ, Zheng W, Motabar O, Southall N, Goldin E, Westbroek W, Stubblefield BK, Sidransky E, Aungst RA, Lea WA, Simeonov A, Leister W, Austin CP. Evaluation of Quinazoline Analogues as Glucocerebrosidase Inhibitors with Chaperone Activity. J Med Chem. 2011;54:1033–1058. doi: 10.1021/jm1008902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Austin CP, Brady LS, Insel TR, Collins FS. NIH Molecular Libraries Initiative. Science. 2004;306:1138–1139. doi: 10.1126/science.1105511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Inglese J, Auld DS, Jadhav A, Johnson RL, Simeonov A, Yasgar A, Zheng W, Austin CP. Quantitative high-throughput screening: a titration-based approach that efficiently identifies biological activities in large chemical libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11473–11478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604348103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouchikhi F, Anizon F, Moreau P. Synthesis and antiproliferative activities of isoindigo and azaisoindigo derivatives. Eur J Med Chem. 2008;43:755–762. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vedadi M, Niesen FH, Allali-Hassani A, Fedorov OY, Finerty PJ, Wasney GA, Yeung R, Arrowsmith C, Ball LJ, Berglund H, Hui R, Marsden BD, Nordlund P, Sundstrom M, Weigelt J, Edwards AM. Chemical screening methods to identify ligands that promote protein stability, protein crystallization, and structure determination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15835–15840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605224103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jerabek-Willemsen M, Wienken CJ, Braun D, Baaske P, Duhr S. Molecular interaction studies using microscale thermophoresis. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2011;9:342–353. doi: 10.1089/adt.2011.0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niesen FH, Berglund H, Vedadi M. The use of differential scanning fluorimetry to detect ligand interactions that promote protein stability. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2212–2221. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.