Abstract

Aims

To examine the clinical effectiveness of angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction (HF-PEF).

Methods and results

Of the 10 570 hospitalized HF-PEF patients, aged ≥65 years, EF ≥40%, in OPTIMIZE-HF (2003–2004), linked to Medicare data (up to 31 December 2008), 3806 were not receiving angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or prior ARB therapy. Of these, 303 (8%) patients received new discharge prescriptions for ARBs. Propensity scores for the receipt of ARBs, estimated for each of the 3806 patients, were used to assemble a cohort of 296 pairs of patients receiving and not receiving ARBs, who were balanced on 114 baseline characteristics. Patients had a mean age of 80 years, mean EF of 55%, 69% were women, and 12% were African American. During 6 years of follow-up, the primary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality or HF hospitalization occurred in 79% (235/296) and 81% (241/296) of patients receiving and not receiving ARBs, respectively [hazard ratio (HR) associated with ARB use 0.88, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.74–1.06; P = 0.179]. ARB use had no association with individual endpoints of all-cause mortality (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.76–1.14; P = 0.509), HF hospitalization (HR 0.90, 95% CI, 0.72–1.14; P = 0.389), or all-cause hospitalization (HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.77–1.08; P = 0.265). These associations remained unchanged when we compared any (prevalent and new prescriptions) ARB use vs. non-use in a separately assembled propensity-matched cohort of 1137 pairs of HF-PEF patients.

Conclusions

In real-world older HF-PEF patients, ARB use was not associated with improved clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Angiotensin receptor blockers, Heart failure, Preserved ejection fraction

Introduction

Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) may improve outcomes in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HF-REF).1–3 However, findings from two major randomized clinical trials (RCTs), the Candesartan in Heart failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM)-Preserved and the Irbesartan in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction Study (I-PRESERVE), suggest that these drugs may not improve outcomes in HF with preserved ejection fraction (HF-PEF).4,5 Although patients in these two RCTs were older than those enrolled in clinical trials of HF-REF, they were younger than HF-PEF patients frequently encountered in real-world clinical practice.6 Further, baseline characteristics of real-world patients are often different from those of their RCT-eligible counterparts,7 while they are similar to those of patients enrolled in registries.8 In addition, patients enrolled in RCTs receive protocol-specified regimens of study drugs with dose titration and clinical and laboratory monitoring for adverse effects and outcomes. All of these differences may lead to important prognostic disparity and potentially limiting generalizability of RCT findings to real-world patients.9 Therefore, in the current study, we examined clinical effectiveness of ARBs in HF-PEF patients in the Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF) registry.10–12

Methods

Data sources and study population

The current study is based on OPTIMIZE-HF, a national registry of hospitalized HF patients, the details of the design and implementation of which have been previously reported.10–12 Briefly, extensive data on baseline demographics, medical history including admission and discharge medications, hospital course, discharge disposition, and physician specialty were collected by chart abstraction from 48 612 hospitalizations due to HF occurring in 259 hospitals in 48 states between March 2003 and December 2004.10 Medications data included angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, ARBs, beta-blockers, aldosterone antagonists, diuretics, digoxin, hydralazine, and long-acting nitrates. Except for beta-blockers, data on individual drugs and dosages were not available for other drugs including ARBs. A primary discharge diagnosis of HF was based on International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes for HF.10,11 Considering that HF patients with EF 40–50% are characteristically and prognostically similar to those with EF >50%,13 we used EF ≥40% to define HF-PEF, and of the 48 612 HF hospitalizations, 20 839 occurred in those with HF-PEF.

For outcomes, we linked OPTIMIZE-HF to Medicare claims data between 1 January 2002 and 31 December 2008, obtained from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare-linked OPTIMIZE-HF patients have been shown to be similar to real-world HF patients in the general Medicare population.8 Of the 20 839 OPTIMIZE-HF hospitalizations, 13 270 could be linked to the Medicare data, which occurred in 11 997 unique patients, 10 889 of whom were ≥65 years of age, of whom 10 570 were discharged alive.14 After excluding 453 patients receiving both ACE inhibitors and aldosterone antagonists, a relative contraindication to the use of ARBs,15 5185 patients receiving ACE inhibitors and 198 patients receiving ARBs were discontinued prior to discharge; 4734 patients were considered eligible for ARB therapy. Because the OPTIMIZE-HF variable for contraindication to ACE inhibitors included prior intolerance due to cough and angioedema, we did not exclude patients based on that variable, as these patients would be expected to receive ARBs.

Assembly of an inception cohort

Because the receipt of study drug prior to study baseline may affect baseline characteristics and cause left censoring, both potential sources for selection bias, we assembled an inception cohort by excluding 928 (20% of 4734) patients who have used ARBs in the past.16–18 Of the remaining 3806 patients, 303 (8%) received a new discharge prescription of ARBs.

Assembly of a balanced cohort

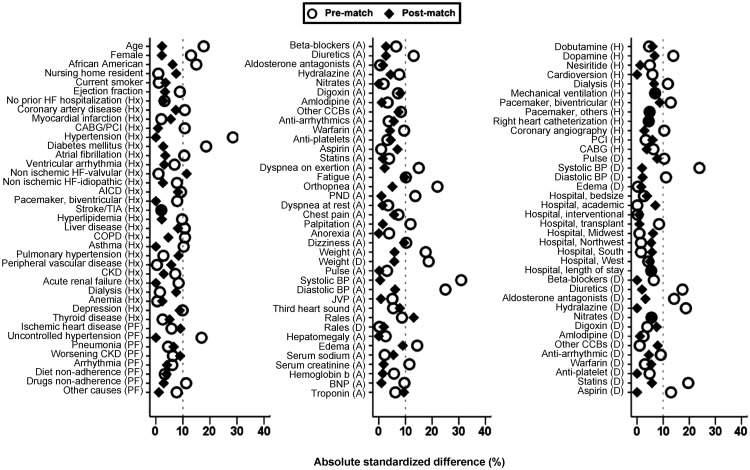

We used propensity scores for the receipt of ARBs to assemble a cohort in which patients receiving and not receiving a new discharge prescription for ARBs would be balanced on all measured baseline characteristics.19,20 We estimated propensity scores for each of the 3806 patients using a non-parsimonious multivariable logistic regression model, in which the receipt of ARBs was the dependent variable, and 114 baseline characteristics displayed in Figure 1 were used as covariates.21–23 Using a greedy matching protocol, we were able to match 296 (98% of 303) patients receiving ARBs with another 296 patients not receiving these drugs who had similar propensity scores for the receipt of these drugs.24,25 Absolute standardized differences were estimated to assess the effectiveness of the propensity score model and are presented as a Love plot (Figure 1).26,27 An absolute standardized difference of 0% would indicate no residual bias and values <10% are considered inconsequential.

Figure 1.

Love plots displaying absolute standardized differences comparing 114* baseline characteristics between older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction receiving new discharge prescriptions for angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), before and after propensity score matching. A, admission; AICD, automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; BP, blood pressure; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CCB, calcium channel blocker; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; D, discharge; H, in-hospital; HF, heart failure; Hx, past medical history; JVP, jugular venous pressure; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PF, precipitating factor; PND, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea; TIA, transient ischaemic attack. *Four regions entered as a single categorical variable in the model, milrinone in hospital and electrophysiological study had no event in matched data as excluded from the figure.

To examine the effect of ARBs in patients receiving background ACE inhibitor therapy as in I-PRESERVE and CHARM-Preserved,4,5 we assembled a second balanced cohort of 437 pairs of patients, of whom 14% were receiving background ACE inhibitor therapy. Finally, to determine clinical effectiveness of any (prevalent use or new prescriptions) ARB use, we assembled a third balanced cohort of 1137 pairs of HF-PEF patients.

Outcomes

The primary outcome for the current analysis was the composite endpoints of all-cause mortality or HF hospitalization during about 6 years of follow-up. Secondary outcomes included individual endpoints of all-cause mortality, HF hospitalization, and all-cause hospitalizations. As mentioned earlier, all outcome data were obtained from Medicare claims data.8,14

Statistical analysis

For baseline descriptive, Pearson's χ2, and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for pre-match, and McNemar's test and paired sample t-test for post-match comparisons were used, as appropriate (Tables 1 and 2). Kaplan–Meier plots and Cox regression analyses were used to determine associations of discharge prescription of ARBs with outcomes during 6 years of follow-up. A formal sensitivity analysis was conducted to estimate the degree of hidden bias that could potentially explain away a significant association among matched patients.28 Subgroup analyses were conducted to determine the homogeneity of association between the use of ARBs and the primary composite endpoint (Figure 3). In addition, we replicated the above process and assembled another propensity-matched cohort, using EF 50% as cut-off for HF-PEF. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with a P-value <0.05 considered significant. SPSS for Windows version 18 was used for data analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction

| Variables [mean ( ± SD) or n (%)] | Before propensity score matching |

After propensity score matching |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of ARBs |

P-value | Use of ARBs |

P-value | |||

| No (n = 3503) | Yes (n = 303) | No (n = 296) | Yes (n = 296) | |||

| Age (years) | 81 (±8) | 80 (±8) | 0.003 | 79 (±8) | 80 (±8) | 0.787 |

| Female | 2200 (63) | 209 (69) | 0.032 | 202 (68) | 205 (69) | 0.851 |

| African American | 271 (8) | 37 (12) | 0.006 | 39 (13) | 33 (11) | 0.512 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 56 (±9) | 55 (±9) | 0.141 | 55 (±9) | 55 (±9) | 0.688 |

| Precipitating factors for hospital admission | ||||||

| Ischaemic heart disease | 363 (10) | 37 (12) | 0.314 | 25 (8) | 33 (11) | 0.332 |

| Uncontrolled hypertension | 262 (8) | 38 (13) | 0.002 | 36 (12) | 36 (12) | 1.000 |

| Pneumonia | 626 (18) | 49 (16) | 0.458 | 41 (14) | 48 (16) | 0.489 |

| Worsening renal function | 276 (8) | 19 (6) | 0.315 | 13 (4) | 19 (6) | 0.377 |

| Arrhythmia | 525 (15) | 39 (13) | 0.320 | 35 (12) | 39 (13) | 0.699 |

| Past medical history | ||||||

| No prior heart failure hospitalization | 459 (13) | 43 (14) | 0.591 | 46 (16) | 43 (15) | 0.818 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1547 (44) | 150 (50) | 0.073 | 135 (46) | 146 (49) | 0.413 |

| Myocardial infarction | 587 (17) | 53 (18) | 0.743 | 46 (16) | 52 (18) | 0.576 |

| Hypertension | 2457 (70) | 249 (82) | <0.001 | 242 (82) | 242 (82) | 1.000 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1254 (36) | 136 (45) | 0.002 | 135 (46) | 131 (44) | 0.807 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1355 (39) | 102 (34) | 0.085 | 106 (36) | 101 (34) | 0.735 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 1010 (29) | 101 (33) | 0.098 | 97 (33) | 100 (34) | 0.859 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 538 (15) | 47 (16) | 0.943 | 41 (14) | 47 (16) | 0.561 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2486 (71) | 205 (68) | 0.224 | 197 (67) | 201 (68) | 0.791 |

| Depression | 413 (12) | 46 (15) | 0.082 | 37 (13) | 46 (16) | 0.328 |

| Admission symptoms and signs | ||||||

| Chest pain | 724 (21) | 72 (24) | 0.204 | 61 (21) | 68 (23) | 0.551 |

| Dyspnoea on exertion | 2119 (61) | 205 (68) | 0.014 | 196 (66) | 199 (67) | 0.857 |

| Dyspnoea at rest | 1483 (42) | 123 (41) | 0.556 | 123 (42) | 121 (41) | 0.932 |

| Orthopnoea | 740 (21) | 93 (31) | <0.001 | 97 (33) | 90 (30) | 0.566 |

| Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea | 361 (10) | 45 (15) | 0.014 | 43 (15) | 42 (14) | 1.000 |

| Palpitation | 111 (3) | 17 (6) | 0.024 | 17 (6) | 16 (5) | 1.000 |

| Weight (kg) | 77 (±21) | 81 (±22) | 0.003 | 79 (±23) | 81 (±23) | 0.464 |

| Pulse (b.p.m.) | 84 (±21) | 83 (±20) | 0.620 | 83 (±22) | 83 (±20) | 0.980 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 144 (±31) | 154 (±32) | <0.001 | 153 (±33) | 153 (±31) | 0.942 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 73 (±18) | 77 (±18) | <0.001 | 78 (±20) | 77 (±17) | 0.444 |

| Jugular venous pressure elevation | 903 (26) | 85 (28) | 0.386 | 83 (28) | 84 (28) | 1.000 |

| Third heart sound | 178 (5) | 12 (4) | 0.390 | 7 (2) | 11 (4) | 0.481 |

| Pulmonary râles | 2189 (63) | 202 (67) | 0.149 | 219 (74) | 198 (67) | 0.076 |

| Lower extremity oedema | 2323 (66) | 221 (73) | 0.019 | 205 (69) | 217 (73) | 0.315 |

| Laboratory values | ||||||

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | 137 (±11) | 136 (±14) | 0.681 | 137 (±10) | 136 (±14) | 0.507 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.8 (±1.5) | 1.6 (±1.4) | 0.057 | 1.6 (±1.1) | 1.6 (±1.2) | 0.827 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 12 (±2) | 12 (±2) | 0.369 | 12 (±2) | 12 (±2) | 0.862 |

| Serum troponin | 538 (15) | 40 (13) | 0.316 | 50 (17) | 40 (14) | 0.295 |

| Serum brain natriuretic peptide | 972 (±922) | 887 (±821) | 0.124 | 886 (±738) | 879 (±798) | 0.907 |

ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Care and hospital characteristics of older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction

| Variables [mean (±SD) or n (%)] | Before propensity score matching |

After propensity score matching |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of ARBs |

P-value | Use of ARBs |

P-value | |||

| No (n = 3503) | Yes (n = 303) | No (n = 296) | Yes (n = 296) | |||

| Admission medications | ||||||

| Beta-blockers | 1744 (50) | 141 (47) | 0.278 | 134 (45) | 138 (47) | 0.807 |

| Diuretics | 2201 (63) | 171 (56) | 0.028 | 166 (56) | 170 (57) | 0.799 |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 158 (5) | 14 (5) | 0.930 | 13 (4) | 14 (5) | 1.000 |

| Digoxin | 625 (18) | 46 (15) | 0.244 | 56 (19) | 44 (15) | 0.235 |

| Hydralazine | 141 (4) | 8 (3) | 0.233 | 6 (2) | 8 (3) | 0.791 |

| Nitrates | 714 (20) | 64 (21) | 0.759 | 63 (21) | 63 (21) | 1.000 |

| Amlodipine | 382 (11) | 30 (10) | 0.589 | 31 (10) | 30 (10) | 1.000 |

| Non-amlodipine calcium channel blockers | 669 (19) | 68 (22) | 0.158 | 55 (19) | 67 (23) | 0.251 |

| Antiarrhythmic drugs | 350 (10) | 27 (9) | 0.546 | 32 (11) | 27 (9) | 0.583 |

| Warfarin | 819 (23) | 59 (20) | 0.121 | 64 (22) | 59 (20) | 0.691 |

| Antiplatelet drugs | 393 (11) | 31 (10) | 0.600 | 27 (9) | 31 (11) | 0.689 |

| Aspirin | 1292 (37) | 113 (37) | 0.887 | 103 (35) | 113 (38) | 0.430 |

| Statins | 967 (28) | 89 (29) | 0.510 | 84 (28) | 86 (29) | 0.926 |

| In-hospital treatment and procedures | ||||||

| Dobutamine | 39 (1) | 5 (2) | 0.402 | 5 (2) | 3 (1) | 0.727 |

| Dopamine | 82 (2) | 2 (1) | 0.056 | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | 0.687 |

| Nesiritide | 313 (9) | 23 (8) | 0.429 | 24 (8) | 23 (8) | 1.000 |

| Right heart catheterization | 69 (2) | 8 (3) | 0.426 | 6 (2) | 8 (3) | 0.791 |

| Coronary angiography | 158 (5) | 21 (7) | 0.056 | 17 (6) | 19 (6) | 0.868 |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | 16 (1) | 3 (1) | 0.206 | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | 1.000 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 24 (1) | 3 (1) | 0.544 | 5 (2) | 3 (1) | 0.727 |

| Cardioversion | 43 (1) | 2 (1) | 0.381 | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 1.000 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 78 (2) | 4 (1) | 0.297 | 2 (1) | 4 (1) | 0.687 |

| Pacemaker–bivent ricular | 19 (0.5) | 6 (2.0) | 0.003 | 1 (0.3) | 4 (1.4) | 0.375 |

| Pacemaker–other | 39 (1.1) | 2 (0.7) | 0.463 | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.7) | 1.000 |

| Dialysis | 186 (5) | 9 (3) | 0.076 | 6 (2) | 9 (3) | 0.607 |

| Discharge medications | ||||||

| Beta-blockers | 1947 (56) | 178 (59) | 0.287 | 173 (58) | 173 (58) | 1.000 |

| Diuretics | 2709 (77) | 255 (84) | 0.006 | 252 (85) | 250 (85) | 0.905 |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 250 (7) | 34 (11) | 0.009 | 36 (12) | 33 (11) | 0.801 |

| Digoxin | 725 (21) | 58 (19) | 0.521 | 65 (22) | 56 (19) | 0.426 |

| Hydralazine | 193 (6) | 6 (2) | 0.008 | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 1.000 |

| Nitrates | 875 (25) | 83 (27) | 0.353 | 72 (24) | 79 (27) | 0.579 |

| Amlodipine | 366 (10) | 34 (11) | 0.674 | 35 (12) | 34 (12) | 1.000 |

| Non-amlodipine calcium channel blockers | 684 (20) | 58 (19) | 0.871 | 49 (17) | 58 (20) | 0.391 |

| Antiarrhythmic drugs | 422 (12) | 28 (9) | 0.147 | 31 (11) | 27 (9) | 0.678 |

| Warfarin | 913 (26) | 75 (25) | 0.618 | 81 (27) | 74 (25) | 0.579 |

| Antiplatelet drugs | 440 (13) | 43 (14) | 0.413 | 43 (15) | 43 (15) | 1.000 |

| Aspirin | 1474 (42) | 147 (49) | 0.030 | 142 (48) | 142 (48) | 1.000 |

| Statins | 964 (28) | 111 (37) | 0.001 | 98 (33) | 106 (36) | 0.526 |

| Length of hospital stay | 6 (±5) | 6 (±5) | 0.380 | 6 (±5) | 6 (±5) | 0.530 |

| Hospital characteristics | ||||||

| Bed size | 381 (±238) | 375 (±226) | 0.672 | 365 (±255) | 373 (±221) | 0.636 |

| Academic | 1397 (40) | 121 (40) | 0.985 | 106 (36) | 116 (39) | 0.453 |

| Interventional | 2628 (75) | 227 (75) | 0.968 | 220 (74) | 221 (75) | 1.000 |

| Transplant | 462 (13) | 49 (16) | 0.144 | 46 (16) | 47 (16) | 1.000 |

| Hospital location by region | 0.910 | 0.626 | ||||

| Midwest | 1044 (30) | 89 (29) | 77 (26) | 85 (29) | ||

| Northeast | 656 (19) | 55 (18) | 48 (16) | 54 (18) | ||

| South | 1146 (33) | 97 (32) | 104 (35) | 96 (32) | ||

| West | 657 (19) | 62 (21) | 67 (23) | 61 (21) | ||

ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; SD, standard deviation.

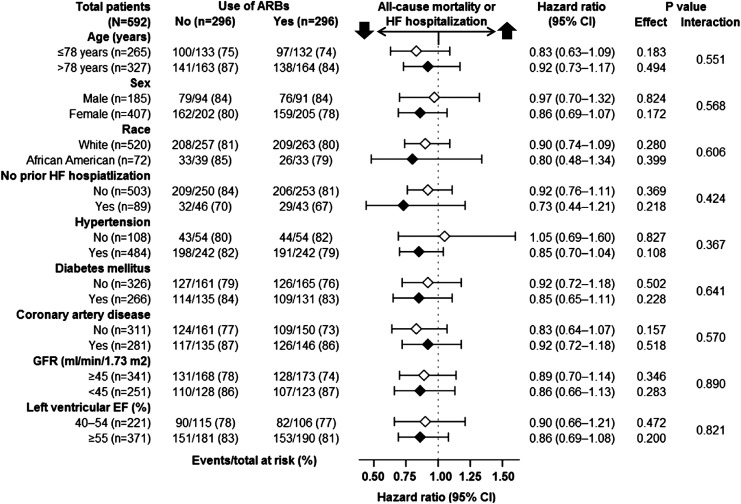

Figure 3.

Association of new discharge prescriptions for angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) with primary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality or HF hospitalization in subgroups of propensity-matched inception cohort of older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. CI, confidence interval; EF, ejection fraction; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Matched patients (n = 592) had a mean [±standard deviation (SD)] age of 80 ( ± 8) years, a mean ( ± SD) left ventricular EF of 55% ( ± 9%), 69% were women, and 12% were African American. Patients receiving ARBs were more likely to be younger, women, African American, had a higher symptom and co-morbidity burden, and to be receiving diuretics and aldosterone antagonists (Tables 1 and 2, Figure 1). These and all other measured baseline characteristics were balanced after matching.

New discharge prescriptions for angiotensin receptor blockers and outcomes

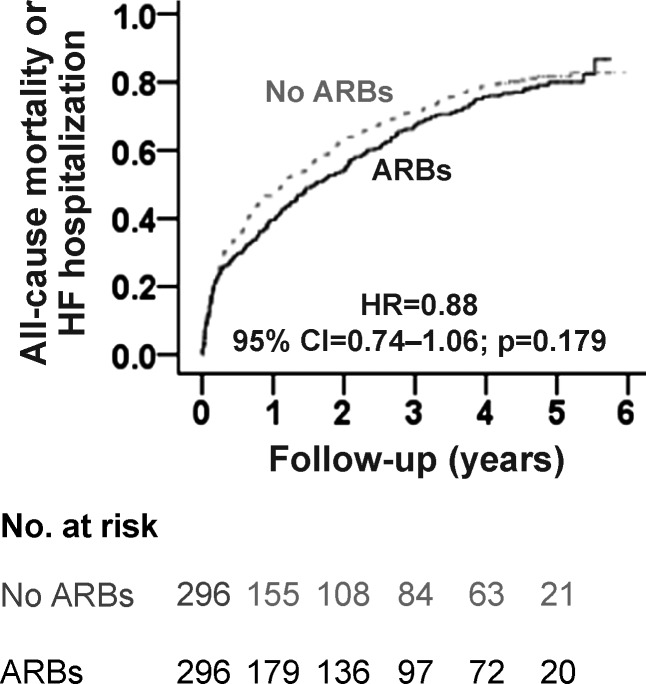

During 6 years of follow-up, the primary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality or HF hospitalization occurred in 79% (235/296) and 81% (241/296) of matched patients receiving and not receiving a new discharge prescription of ARBs, respectively [hazard ratio (HR) when the use of ARBs was compared with their non-use, 0.88; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.74–1.06; P = 0.179; Figure 2, Table 3]. Because of the non-significant association between ARB use and the primary outcome, no formal sensitivity analysis could be performed. There was no heterogeneity in the association between ARB use and the composite primary endpoint across various clinically relevant subgroups of patients (Figure 3). A new discharge prescription for ARBs had no significant association with individual endpoints of all-cause mortality, HF hospitalization, and all-cause hospitalization (Table 3). All associations were similar when EF >50% was used to define HF-PEF.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier plot for primary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality or heart failure hospitalization in a propensity-matched inception cohort of older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction receiving and not receiving new discharge prescriptions for angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs). CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Table 3.

Association of new discharge prescription of angiotensin receptor blockers with outcomes in propensity-matched older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction

| Outcomes | % (events) |

Absolute risk differencea | Hazard ratiob (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of ARBs |

|||||

| No (n = 296) | Yes (n = 296) | ||||

| All-cause mortality or HF hospitalization | 81% (241) | 79% (235) | –2% | 0.88 (0.74–1.06) | 0.179 |

| All-cause mortality | 64% (190) | 63% (185) | –1% | 0.93 (0.76–1.14) | 0.509 |

| HF hospitalization | 49% (144) | 48% (143) | –1% | 0.90 (0.72–1.14) | 0.389 |

| All-cause hospitalization | 92% (271) | 89% (264) | –3% | 0.91 (0.77–1.08) | 0.265 |

ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CI, confidence interval; HF, heart failure.

aAbsolute risk differences were calculated by subtracting percentage events in patients not receiving ARBs from those receiving those drugs.

bHazard ratios comparing patients receiving ARBs vs. those not receiving those drugs.

Outcomes in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction receiving background angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy

Among the 874 matched patients receiving background therapy with ACE inhibitors, a new prescription for ARBs had no association with the primary composite endpoint (HR associated with ARB use, 0.97; 95% CI 0.84–1.12; P = 0.657) or any secondary endpoints.

Any (new or continuation) prescription for angiotensin receptor blockers and outcomes

The primary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality or HF hospitalization occurred in 83% (946/1137) and 83% (942/1137) of matched patients receiving and not receiving any (new or continuation) discharge prescription for ARBs, respectively (HR associated with ARB use, 0.96; 95% CI 0.88–1.05; P = 0.414; Table 4). Any prescriptions of ARBs had a significant association with all-cause mortality (HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.82–0.995; P = 0.040), but not with hospitalizations (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association of any (new or continuation) discharge prescription of angiotensin receptor blockers with outcomes in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction

| Outcomes | % (events) |

Absolute risk differencea | Hazard ratiob (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of ARBs |

|||||

| No (n = 1137) | Yes (n = 1137) | ||||

| All-cause mortality or HF hospitalization | 83% (942) | 83% (946) | 0% | 0.96 (0.88–1.05) | 0.414 |

| All-cause mortality | 70% (798) | 67% (760) | –3% | 0.90 (0.82–0.995) | 0.040 |

| HF hospitalization | 48% (546) | 49% (559) | +1% | 0.98 (0.87–1.10) | 0.753 |

| All-cause hospitalization | 89% (1007) | 91% (1034) | +2% | 1.03 (0.94–1.12) | 0.563 |

ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CI, confidence interval; HF, heart failure.

aAbsolute risk differences were calculated by subtracting percentage events in patients not receiving ARBs from those receiving those drugs.

bHazard ratios comparing patients receiving ARBs vs. those not receiving those drugs.

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in OPTIMIZE-HF and in randomized controlled trials of angiotensin receptor blockers

Compared with CHARM-Preserved and I-PRESERVE, patients in our study were about a decade older, had a similar co-morbidity profile except for a higher prevalence of diabetes, and received similar background therapy except for no background ACE inhibitor therapy (Table 5). In addition, all HF-PEF patients in our study had prior HF hospitalization and higher annual rates for mortality and hospitalization compared with those in the RCTs (Table 5).

Table 5.

Baseline characteristics and outcomes in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction eligible for angiotensin receptor blocker therapy in propensity-matched inception cohorts of OPTIMIZE-HF, receiving and not receiving background angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy (left two columns), and those enrolled in randomized clinical trials of angiotensin receptor blockers

| Variables [mean (±SD) or n (%)] | OPTIMIZE-HF, not receiving background ACE inhibitor therapy (n = 592) | OPTIMIZE-HF, receiving background ACE inhibitor therapy (n = 874) | I-PRESERVE (n = 4128) | CHARM-Preserved (n = 3023) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 80 (±8) | 80 (±8) | 72 (±7) | 67 (±11) |

| Female | 69 | 70 | 63 | 40 |

| African American | 12 | 11 | 2 | 4 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 55 (±9) | 55 (±9) | 59 (±9) | 54 (±9) |

| Medical history | ||||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 17 | 17 | 23 | 44 |

| Hypertension | 82 | 82 | 88 | 64 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 45 | 45 | 27 | 28 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 35 | 34 | 35 | 29 |

| Medications | ||||

| ACE inhibitors | 0 | 14 | 25 | 19 |

| Beta-blockers | 58 | 57 | 59 | 56 |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 12 | 9 | 15 | 12 |

| Diuretics | 85 | 83 | 83 | 75 |

| Digoxin | 20 | 16 | 14 | 28 |

| Antiarrhythmic drugs | 10 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Admission clinical and laboratory data | ||||

| Pulse (b.p.m.) | 83 (±21) | 82 (±21) | 71 (±11) | 71 (±12) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 153 (±32) | 155 (±32) | 136 (±15) | 136 (±18) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 77 (±18) | 77 (±18) | 79 (±9) | 78 (±11) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.6 (±1.2) | 1.6 (±1.1) | 1.0 (±0.3) | – |

| Index heart failure hospitalization | 100 | 100 | 44a | 69 |

| Annual all-cause mortality | 11 | 11 | 4.3 | 4.5 |

| Annual heart failure hospitalization | 8.1 | 8.0 | 3.2 | 4.9 |

| Annual all-cause hospitalization | 15 | 15 | 11 | — |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; SD, standard deviation.

aWithin the 6 months prior to randomization.

Discussion

Findings from the current analysis demonstrate that a new discharge prescription for ARBs was not associated with improvement in post-discharge clinical outcomes in a wide spectrum of older HF-PEF patients not receiving background ACE inhibitor therapy. Similar associations were observed with any (new or continuation) prescription for ARBs and in those receiving background ACE inhibitor therapy. Despite some similarities in baseline characteristics with HF-PEF patients in I-PRESERVE, those in our study were older, with greater frequency of co-morbid conditions, and had poorer prognosis. Our findings based on a rigorously conducted propensity-matched inception cohort of older HF-PEF patients are consistent with those from the RCTs and provide additional insights into the role of ARBs in real-world older HF-PEF patients.

Similarities between our findings and those from RCTs of ARBs and ACE inhibitors in HF-PEF suggest that these drugs may not significantly improve outcomes in HF-PEF.4,5,29 Although, unlike ACE inhibitors,30,31 ARBs did not reduce mortality in HF-REF,1,2 they reduced HF hospitalization in these patients,1,2 probably by preventing maladaptive ventricular remodelling and attenuating disease progression.30–32 While in CHARM-Preserved there was a modest reduction in HF hospitalization, ARBs had no effect on HF hospitalization in I-PRESERVE.4,5 We also did not observe any association between ARB use and HF hospitalization in older patients with HF-PEF. This may be potentially explained by the older age of HF-PEF patients in our study and in I-PRESERVE. HF hospitalization rates seem to decline with increasing age and may be adversely affected by competing risk of death.33

Properly designed and conducted RCTs are the gold standard for efficacy of drug therapy, and the findings from the I-PRESERVE and CHARM-Preserved studies have clearly established the lack of efficacy of ARBs in HF-PEF patients. However, as demonstrated in our Table 5, there are important characteristic and prognostic differences between HF-PEF patients enrolled in RCTs and registries such as OPTIMIZE-HF. Yet, it is unlikely that the efficacy of ARBs in real-world HF-PEF patients would be examined in RCTs. When RCTs are impractical or unethical, findings from multiple properly designed propensity-matched studies can be a source of level B evidence.34 This is important as HF guideline recommendations are often based on level C evidence.35 In particular, our use of >100 measured baseline characteristics substantially reduced bias due to unmeasured covariates as clinical variables are often closely correlated. For an unmeasured covariate not included in our propensity model, to act as a confounder, in addition to being a predictor of both outcome and ARB use, it must not be strongly correlated with any of the >100 covariates used in our study, which is an unlikely possibility. Further, our use of an inception cohort allowed us to eliminate bias due to left censoring and the effect of prevalent ARB use on baseline characteristics.16,18

Our study has several limitations. The small sample size of HF-PEF patients receiving new prescriptions for ARBs in OPTIMIZE-HF has underpowered our inception cohort study. However, we observed similar associations with any (new or prevalent) use of ARBs. Additionally, OPTIMIZE-HF did not collect data on ARB-specific contraindications that excluded cough and angioedema. We also had no data on individual ARBs and their dosages and post-discharge adherence.

In conclusion, in older HF-PEF patients, the use of ARBs was not associated with reduction in total mortality or hospitalization. Taken together with the findings from the I-PRESERVED and CHARM-Preserved studies, findings from our study provide additional insights into the clinical effectiveness of ARBs in real-world older HF-PEF patients and suggest that ARBs may be of no clinical benefit in HF-PEF.

Funding

A.A. is supported by the National Institutes of Health through a grant (R01-HL097047) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and a generous gift from Ms. Jean B. Morris of Birmingham, AL. R.M.A. is supported by the UAB CTSA grant (5UL1 RR025777). OPTIMIZE-HF was funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

Conflicts of interest: G.C.F. has been consultant to Medtronic, Novartis, and Gambro. D.W.K. has received research funding from Novartis, has been consultant for Boston Scientific, Abbott and Relypsa, has been on an advisory board for Relypsa, and has stock ownership (significant) for Gilead and stock options for Relypsa. M.G. has acted as consultant for the following: Abbott Laboratories, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Cardiorentis Ltd, CorThera, Cytokinetics, CytoPherx Inc, DebioPharm SA, Errekappa Terapeutici, GlaxoSmithKline, Ikaria, Intersection Medical Inc., Johnson & Johnson, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis Pharma AG, Ono Pharmaceuticals USA, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Palatin Technologies, Pericor Therapeutics, Protein Design Laboratories, Sanofi-Aventis, Sigma Tau, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Sticares InterACT, Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America Inc., and Trevena Therapeutics; and has received significant ( >US$10 000) support from Bayer Schering Pharma AG, DebioPharm Sa, Medtronic, Novartis Pharma AG, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Sigma Tau, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Sticares InterACT, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America Inc. All other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Authors' contributions: A.A., G.C.F., I.B.A., and T.E.L. conceived the study hypothesis and design, and K.P., G.C.F., and A.A. wrote the first draft. A.A. and K.P. conducted statistical analyses in collaboration with T.E.L. and I.B.A. All authors interpreted the data, participated in critical revision of the paper for important intellectual content, and approved the final version of the article. A.A., K.P., and I.B.A. had full access to the data.

References

- 1.Cohn JN, Tognoni G. A randomized trial of the angiotensin-receptor blocker valsartan in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1667–1675. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Granger CB, McMurray JJ, Yusuf S, Held P, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Ostergren J, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function intolerant to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Alternative trial. Lancet. 2003;362:772–776. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMurray JJ, Ostergren J, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Held P, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Yusuf S, Pfeffer MA. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function taking angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Added trial. Lancet. 2003;362:767–771. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14283-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massie BM, Carson PE, McMurray JJ, Komajda M, McKelvie R, Zile MR, Anderson S, Donovan M, Iverson E, Staiger C, Ptaszynska A, Investigators IP. Irbesartan in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2456–2467. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yusuf S, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Held P, McMurray JJ, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Ostergren J CHARM Investigators, Committees. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction: the CHARM-Preserved Trial. Lancet. 2003;362:777–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masoudi FA, Havranek EP, Smith G, Fish RH, Steiner JF, Ordin DL, Krumholz HM. Gender, age, heart failure with preserved left ventricular systolic function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:217–223. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02696-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masoudi FA, Havranek EP, Wolfe P, Gross CP, Rathore SS, Steiner JF, Ordin DL, Krumholz HM. Most hospitalized older persons do not meet the enrollment criteria for clinical trials in heart failure. Am Heart J. 2003;146:250–257. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00189-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtis LH, Greiner MA, Hammill BG, DiMartino LD, Shea AM, Hernandez AF, Fonarow GC. Representativeness of a national heart failure quality-of-care registry: comparison of OPTIMIZE-HF and non-OPTIMIZE-HF Medicare patients. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:377–384. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.822692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Boer SP, Lenzen MJ, Oemrawsingh RM, Simsek C, Duckers HJ, van der Giessen WJ, Serruys PW, Boersma E. Evaluating the ‘all-comers’ design: a comparison of participants in two ‘all-comers’ PCI trials with non-participants. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2161–2167. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Gattis WA, Gheorghiade M, Greenberg B, O'Connor CM, Yancy CW, Young J. Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF): rationale and design. Am Heart J. 2004;148:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Stough WG, Gheorghiade M, Greenberg BH, O'Connor CM, Pieper K, Sun JL, Yancy C, Young JB. Association between performance measures and clinical outcomes for patients hospitalized with heart failure. JAMA. 2007;297:61–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gheorghiade M, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Greenberg BH, O'Connor CM, She LL, Stough WG, Yancy CW, Young JB, Fonarow GC. Systolic blood pressure at admission, clinical characteristics, and outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute heart failure. JAMA. 2006;296:2217–2226. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.18.2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fonarow GC, Stough WG, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Gheorghiade M, Greenberg BH, O'Connor CM, Sun JL, Yancy CW, Young JB. Characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients with preserved systolic function hospitalized for heart failure: a report from the OPTIMIZE-HF Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:768–777. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Kilgore ML, Arora T, Mujib M, Ekundayo OJ, Aban IB, Feller MA, Desai RV, Love TE, Allman RM, Fonarow GC, Ahmed A. Design and rationale of studies of neurohormonal blockade and outcomes in diastolic heart failure using OPTIMIZE-HF registry linked to Medicare data. Int J Cardiol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.10.089. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.10.089. Published online ahead of print November 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dickstein K, Cohen-Solal A, Filippatos G, McMurray JJ, Ponikowski P, Poole-Wilson PA, Stromberg A, van Veldhuisen DJ, Atar D, Hoes AW, Keren A, Mebazaa A, Nieminen M, Priori SG, Swedberg K. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:933–989. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danaei G, Tavakkoli M, Hernan MA. Bias in observational studies of prevalent users: lessons for comparative effectiveness research from a meta-analysis of statins. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:250–262. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernan MA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Robins JM. A structural approach to selection bias. Epidemiology. 2004;15:615–625. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000135174.63482.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ray WA. Evaluating medication effects outside of clinical trials: new-user designs. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:915–920. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubin DB. Using propensity score to help design observational studies: application to the tobacco litigation. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol. 2001;2:169–188. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmed A, Husain A, Love TE, Gambassi G, Dell'Italia LJ, Francis GS, Gheorghiade M, Allman RM, Meleth S, Bourge RC. Heart failure, chronic diuretic use, and increase in mortality and hospitalization: an observational study using propensity score methods. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1431–1439. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deedwania PC, Ahmed MI, Feller MA, Aban IB, Love TE, Pitt B, Ahmed A. Impact of diabetes mellitus on outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction and systolic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:551–559. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Filippatos GS, Ahmed MI, Gladden JD, Mujib M, Aban IB, Love TE, Sanders PW, Pitt B, Anker SD, Ahmed A. Hyperuricaemia, chronic kidney disease, and outcomes in heart failure: potential mechanistic insights from epidemiological data. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:712–720. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adamopoulos C, Meyer P, Desai RV, Karatzidou K, Ovalle F, White M, Aban I, Love TE, Deedwania P, Anker SD, Ahmed A. Absence of obesity paradox in patients with chronic heart failure and diabetes mellitus: a propensity-matched study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:200–206. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu AH, Pitt B, Anker SD, Vincent J, Mujib M, Ahmed A. Association of obesity and survival in systolic heart failure after acute myocardial infarction: potential confounding by age. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12:566–573. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed MI, White M, Ekundayo OJ, Love TE, Aban I, Liu B, Aronow WS, Ahmed A. A history of atrial fibrillation and outcomes in chronic advanced systolic heart failure: a propensity-matched study. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2029–2037. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Filippatos GS, Desai RV, Ahmed MI, Fonarow GC, Love TE, Aban IB, Iskandrian AE, Konstam MA, Ahmed A. Hypoalbuminaemia and incident heart failure in older adults. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:1078–1086. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenbaum PR. Sensitivity to hidden bias. In: Rosenbaum PR, editor. Observational Studies. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. pp. p105–170. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cleland JG, Tendera M, Adamus J, Freemantle N, Polonski L, Taylor J. The perindopril in elderly people with chronic heart failure (PEP-CHF) study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2338–2345. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The CONSENSUS Trial Study Group. Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure. Results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS) N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1429–1435. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706043162301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The SOLVD Investigators. Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:293–302. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108013250501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdulla J, Barlera S, Latini R, Kjoller-Hansen L, Sogaard P, Christensen E, Kober L, Torp-Pedersen C. A systematic review: effect of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition on left ventricular volumes and ejection fraction in patients with a myocardial infarction and in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feller MA, Mujib M, Zhang Y, Ekundayo OJ, Aban IB, Fonarow GC, Allman RM, Ahmed A. Baseline characteristics, quality of care, and outcomes of younger and older Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with heart failure: findings from the Alabama Heart Failure Project. Int J Cardiol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.05.003. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.05.003. Published online ahead of print May 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michels KB, Braunwald E. Estimating treatment effects from observational data: dissonant and resonant notes from the SYMPHONY trials. JAMA. 2002;287:3130–3132. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.23.3130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tricoci P, Allen JM, Kramer JM, Califf RM, Smith SC., Jr. Scientific evidence underlying the ACC/AHA clinical practice guidelines. JAMA. 2009;301:831–841. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]