Abstract

Objective

Studies have repeatedly found that providers miss 70-90% of opportunities to express empathy. Our study sought to characterize provider responses to patients’ emotions, with the overall goal of better understanding reasons for lack of empathic response.

Methods

We analyzed 47 visits between patients and their providers. We defined empathic opportunities as instances where patients expressed a strong negative emotion. We then developed thematic categories to describe provider response.

Results

We found a total of 29 empathic opportunities within 21 visits. Provider responses were categorized as ignore, dismiss, elicit information, problem-solve, or empathize. An empathic statement occurred at some point in the response sequence in 13/29 opportunities (45%). When problem-solving was the initial response, empathic statements rarely occurred in subsequent dialogue. Among the 16 instances with no empathic statements, providers engaged in problem-solving in 8 (50%).

Conclusion

Similar to other studies, we found providers missed most opportunities to respond empathically to patient emotion. Yet contrary to common understanding, providers often addressed the problem underlying the emotion, especially when the problem involved logistical or biomedical issues, as opposed to grief.

Practice Implications

With enhanced awareness, providers may better recognize situations where they can offer empathy in addition to problem-solving.

1. Introduction

Empathy is a central component of therapeutic patient-provider relationships,1;2 and has been shown to positively influence health outcomes.3 Provider empathy can be defined as the socio-emotional competence to understand the patient s situation, perspective, and feelings, to communicate that understanding and check its accuracy, and to act on that understanding with the patient in a helpful (therapeutic) way.4;5 The ways in which providers respond to patient expression of emotion have been characterized by previous studies, which have demonstrated that providers often do not respond empathically to emotional distress.6-11

Comparatively few studies have sought to understand why providers fail to respond empathically. It has been suggested that providers may not always respond to emotions appropriately because they feel uncomfortable with strong emotions, because they are too focused on other tasks to recognize the emotions as they occur, or because they feel there is not enough time to respond.12 In order to better characterize missed empathic opportunities, investigators have studied various factors that might influence provider responses. One study found that oncologists are more likely to respond empathically to more severe expressions of emotions and are more likely to respond to sadness than to fear.10 Another study demonstrated that younger providers and those with a ‘socioemotional’ personality orientation missed fewer empathic opportunities.13

Studies to date have not explored the functional nature of provider responses to patients’ expression of emotions in depth, as a means to better understand what actually happens during missed empathic opportunities. In the current study, we characterized provider responses to patients’ emotions, focusing on how providers respond non-empathically as well as empathically, with the overall goal of better understanding provider responses that fail to directly acknowledge patient emotions.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design, subjects, and setting

Data for this study were collected as part of the Enhancing Communication and HIV Outcomes (ECHO) study, which has been previously described14;15 The study included 45 providers and 418 of their HIV-infected patients at four sites: Baltimore, Detroit, New York, and Portland. The study was IRB-approved at each site. Providers included physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants providing primary care to HIV-infected patients. Eligible patients were over 18 and English-speaking. Visits between participant providers and patients were audio recorded and transcribed.

2.2. Identification of patient emotional cues

We defined patient cues as instances in which patients explicitly or implicitly indicated the experience of significant negative emotion. Explicit indications of emotion occurred whenever the patient named the emotion itself, whereas implicit indications included discussions where the patient did not name the emotion but reported to the provider that they were experiencing an emotional situation such as death or illness of a loved one, significant life concerns or changes (e.g., lost job, unable to pay bills), or diagnoses of serious illness (e.g., cancer). We believed that explicit statements of emotion would not capture all instances of significant negative emotion, so we included situations that we judged to have been readily identifiable to providers as being laden with underlying negative emotion. Previous studies have used more8 or less6;11 conservative criteria to define “cues.”16 We categorized patient cues as related to psychosocial issues (logistical life problems, family strain, or death/illness of a loved one), or biomedical concerns.

Because we felt that the phenomenon of provider response (or nonresponse) to various other types of emotion might be different, we excluded statements of physical complaints unaccompanied by a statement of emotion (“I haven’t been feeling like eating good lately at all”), relations of past experiences of negative emotion (“I had a little period of depression there for a little while”), opportunities for praise (“My [CD4 cell] count came up! Did you look at ‘em?”), positive emotions (“She’s never felt me be so happy as I am right now.”), or expressions of annoyance or minor frustration (“It’s been a hassle really.”)

2.3. Selection of audiotapes

Our study focused on a subset of data collected in the ECHO study. Our sampling strategy involved random selection, one by one, from the entire pool of transcripts. After each transcript was selected, we reviewed it for the presence of an emotional cue. If a cue was present, then we analyzed provider response to that cue and no longer reviewed transcripts from that provider (even if one was randomly selected subsequently). This sampling strategy ensured that each cue-containing transcript we analyzed was from a unique provider. We continued sampling until we reached thematic saturation.17;18

2.4. Qualitative analysis of provider response

Two investigators independently analyzed all patient cues and subsequent provider response sequences, meeting regularly to discuss findings and reach consensus regarding classification. If a behavior was not adequately described by our existing categories, we added new categories or refined older ones. Our initial approach to describing provider response was informed by previous classification schemes developed by Suchman et al. (1997),11 Levinson et al. (2000),6 and Bylund and Makoul (2002)9, which typically described provider responses as belonging to two broad types: empathic or positive responses (e.g. supportive, acknowledging, empathic, encouraging, or confirming) and missed empathic opportunities or negative responses (e.g. empathic opportunity terminator, denial, or inadequate acknowledgement). However, through an iterative consensus-building process, we developed a descriptive classification scheme that had two operational features worth noting. First, we examined different types of provider response sequentially. Therefore, the occurrence of one response type did not exclude the possibility of other response types. This process also allowed for provider responses to be analyzed and understood in the order that they occurred. Provider response sequences were followed until either the patient or provider changed the topic. If a cue was revisited later in the encounter, the recurrence of the cue and subsequent provider responses were considered as an extension of the original cue and provider response sequence. This sequential approach has recently been described as a feature of the VR-CoDES-P analytic system. 19

Second, because our descriptive analysis took into account meaning, context, and provider intent, each unique category did not necessarily correspond with a single provider utterance. More often, several provider utterances or turns of speech received a single categorization, because together, they represented a single response type. Using a similar rationale, a single turn of speech might have been considered to have two or more response types if several different types of responses were represented.

After developing a final set of thematic categories, we searched for dominant patterns of provider responses and examined their relation to each other, and to the types of emotional cues presented by patients. We then further examined these patterns and relationships in an effort to understand both empathic and non-empathic responses to patients’ emotional cues.

3. Results

3.1. Patient cues

Our study sample included 21 encounters containing at least one patient cue. The 21 patients had a mean age of 44.2 years, 9 (43%) were female, and 11 (52%) were African American. There were no significant difference in terms of age, sex, or race/ethnicity between the 21 patients with empathic opportunities and those in the complete dataset.

In those 21 encounters, 29 cues occurred. Twenty of the cues involved psychosocial issues (death/illness of loved one, family strain, or logistical life problems such as financial stress or legal problems) and 9 involved biomedical concerns (Table 1). Because providers could have more than one response to each patient cue, we found 63 distinct provider responses following the 29 cues.

Table 1.

Subject of Patient Cues

| Subject | Number of Cues | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Biomedical concern | 9 | “I’m always worried about my weight. You know, like I said, everything, it should be okay, my weight. But I’m always worrying because I feel like I’m getting’ skinny.” |

| Logistical life problem (financial stress, unemployment, legal troubles) | 4 | “I’m in a really bad low right now because I was supposed to go back to work on the 29th.” |

| Death/illness of loved one | 6 | “My auntie died. Had to make funeral arrangements.” |

| Family strain | 10 | “We separated. We still, we trying to get things to get back together. She won’t even.” |

3.2. Types of provider response

We identified five distinct types of provider response: ignore/change topic, dismiss/minimize, elicit information, problem-solving, and empathic response. These responses are described below and summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Coding Scheme for Provider Responses

| Provider Response Type | Definition | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ignore/change topic | No acknowledgement that patient had stated an emotion or concern | Provider: | You have never had this feeling before? |

| Patient: | No not like this. It scares me. | ||

| Provider | mhm. The system is slow today. Chest pain? | ||

|

| |||

| Dismiss/minimize | Denies legitimacy of the source of patient’s concerns | Patient: | But I’m always worrying because I feel like I’m getting’ skinny. |

| Provider: | Nope, we don’t see any significant changes in that respect, okay? | ||

|

| |||

| Elicit information | Elicits details about the situation, circumstances, or emotions surrounding the patient’s cue | Patient: | We separated. We still, we trying to get things to get back together. She won’t even… |

| Provider: | So, you were doing so well, so what do you think? What was it? | ||

|

| |||

| Problem-solving | Explicitly addresses patient’s cue by focusing on giving advice or seeking a solution | Patient: | But sometimes I feel like bad about myself, you know? |

| Provider: | Ohhh. | ||

| Patient: | Depressed. | ||

| Provider: | Ohhh. | ||

| Patient: | I get in depression and start thinking, oh well, I feel like- | ||

| Provider: | Now have you been in a group, in a support group before? | ||

| Patient: | No. | ||

| Provider: | For HIV? I think that might really help. | ||

|

| |||

| Empathic response | Explicitly addresses patient’s cue by explicitly acknowledging patient’s emotion or difficult situation | Patient: | Make me feel I’m 90 years old, withered old man now. And it bothers me too. That bothers me a whole lot. It bothers me. |

| Provider: | Okay. I wish there was something else I could do. It sounds like it’s really affecting your state of mind, too. | ||

3.2.1. Ignore/change topic

The response type “Ignore/Change Topic” constituted 8 of the 63 provider responses (11%) to 7/29 cues (24%). Responses in the “ignore/change topic” category did not acknowledge that the patient had stated or suggested an emotion or concern. In these instances, the provider either continued with the previous line of conversation or shifted the topic away from the patient’s emotional state, as illustrated in the following example, where the patient conveys her fear about pain and debilitation.

| Patient: | I mean I’ve tried soakin’ in hot baths, I’ve tried the heating pad, ain’t nothin’ helpin’ me at all…… I just don’t want to go crippled. (Cue) |

| Provider: | Any problem with fevers? (Ignore/change topic) |

3.2.2. Dismiss/minimize

The response type “dismiss/minimize” occurred in only 2 of 63 responses (3%) to 2 of 29 cues (7%). These responses acknowledged the patient’s concern but not its legitimacy. In the following encounter, the provider recognizes and addresses the patient’s concern in a way that may have been intended to be reassuring but delegitimizes his perspective.

| Patient: | But I’m always worrying because I feel like I’m getting skinny. (Cue) |

| Provider: | Nope, we don’t see any significant changes in that respect, okay? (Dismiss/Minimize) |

3.3.3. Elicit information

“Elicit information” was the most common response type, accounting for 23 of 63 total provider responses (37%) to 21/29 cues (72%). This response type encouraged patients to elaborate on the situation, circumstances or emotions surrounding their cues without the apparent goal of problem solving. For example, provider responses like “Tell me about your, your Auntie died?” facilitated patient narrative, dialogue, and provider understanding. In most cases, this line of questioning was focused on the situation (“Okay, so what happened?”- 21 occurrences), rather than on the patient’s emotional response (“So how is all this affecting you?” -3 occurrences).

3.3.4. Problem-solving

“Problem-solving” was a commonly observed response type, occurring in 16 of 63 responses (25%) to 12/29 cues (41%). When engaging in “problem-solving,” providers explicitly addressed the patient’s cue by asking questions or making recommendations with the intention of solving the problem underlying the patient’s emotional distress. “Problem-solving” responses did not explicitly acknowledge the patient’s emotions. In one example, after a patient expresses apprehension about revealing his HIV status to his family, his provider responds by giving advice: “That’s your decision. You don’t have to tell anybody you don’t want to tell.” In the following exchange, the patient relates distress related to disfiguring Kaposi’s Sarcoma. The provider asks questions specifically addressing treatment for the sarcoma, with the apparent intention of eliminating the source of the patient’s distress.

3.3.5. Empathic response

“Empathic responses” occurred in 14 of 63 provider responses (22%) to 13/29 cues (45%). We defined “empathic responses” as explicitly demonstrating understanding and recognition of the circumstances or emotions surrounding a patient’s concern. Providers often demonstrated empathy by expressing their understanding of patients’ difficult circumstances (“It sounds like it’s really affecting your state of mind, too”) or by naming patients’ emotions (“It’s a scary thing”) Providers also expressed empathy by legitimizing patients’ emotions and experiences (“Like any good father, you want what’s best for them”) and by expressing sympathy for patients’ struggles (“I’m sorry it’s been such a tough month”).

In most cases, providers responded with empathy after an extended exchange with the patient regarding the situation or concern. However, in some cases, providers made an empathic response immediately after the patient presented a cue (e.g., “Oh my goodness, I’m sorry to hear that”). We considered these statements empathic responses because they demonstrated providers’ understanding, even without further explanation by the patient, that the patient had experienced something negative.

3.4. Sequential nature of provider response

Providers typically offered more than one type of response to a patient cue. In the following example, the provider responds to the patient’s cue by first clarifying and eliciting details. After the patient explains the situation, the provider offers an empathic response by legitimizing the patient’s experience. He then goes on to talk about a solution: seeking mental health counseling.

As illustrated, providers’ responses to patients’ emotions often extended beyond the first utterance or initial response to the patient’s cue. Consideration of the complete provider response often revealed that the provider accomplished several aims during the conversation following the cue, including offering empathic responses and solutions or allowing patients to speak more about their concerns.

3.5. Patterns of provider response

Common sequential patterns of provider responses to patient cues are illustrated in Figure 1, and a complete listing of all patient cues and their corresponding response sequences can be found in the Appendix. “Elicit information” was the most frequent initial response to a patient’s cue. It often furthered discussion of the patient’s concerns and led to “problem-solving” and/or “empathic responses.” “Problem-solving,” “ignore/change topic,” and “dismiss/minimize” were less common as initial responses, but when occurring as initial responses, tended to terminate or limit further discussion of the patient’s situation or feelings.

Figure 1.

Dominant Patterns of Provider Response

The type of response initially offered seemed to be associated with the subsequent occurrence of empathic responses in the dialogue (Table 3). When empathy occurred at some point in the sequence, it almost always was either the first response or followed the elicitation of further information. Empathy never occurred following a cue where the initial response was dismiss/minimize or ignore/change topic, and rarely occurred following problem-solving.

Table 3.

Initial Provider Responses and Subsequent Occurrences of Empathic Responses

| Provider Response Type | Initial Response (Number of Cues) | Empathic Response at Any Point (Number of Cues) |

|---|---|---|

| Ignore/change topic | 1 | 0 |

| Dismiss/minimize | 3 | 0 |

| Elicit information | 16 | 9 |

| Problem-solving | 6 | 1 |

| Empathic response | 3 | 3 |

| Total | 29 | 13 |

Further, providers seemed to respond differently depending on the subject of the cues. Providers were more likely to respond with problem-solving than empathy when patients’ cues involved logistical life problems and biomedical concerns. In contrast, providers were more likely to respond with empathy when cues concerned family strain or death/illness of loved ones (Table 4).

Table 4.

Provider Responses by Subject of Patient Cue

| Subject of Cue | Number of Cues* | Elicited empathic response (number of cues) | Elicited problem-solving (number of cues) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomedical concern | 9 | 2 | 4 |

| Logistical life problems | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Family/relationship strain | 10 | 6 | 4 |

| Death or illness of a loved one | 6 | 4 | 1 |

There were a total of 29 distinct patient cues. The number of cues in columns 3 and 3 do not necessarily add to equal the number of cues in column 2, because we have not listed the number of cues that elicited neither empathic responses nor problem-solving. Additionally, the cues that make up column 3 and column 4 are not mutually exclusive; some cues elicited both and contributed to both columns.

3.6. Conceptual relationship between empathy and problem-solving

In 16 of 29 patient cues, providers did not offer empathic responses. In 8 (50%) of those instances, providers engaged in “problem-solving.” Although “problem-solving” does not explicitly acknowledge patient emotion and has traditionally been considered “missed opportunity,” we recognized that in contrast to other types of provider response, “problem-solving” is a direct attempt to address the patient’s cue. When providers engage in “problem-solving,” they implicitly acknowledge that the patient is experiencing some difficulty or emotional distress and attempt to address that by solving the problem surrounding or underlying the emotional distress.

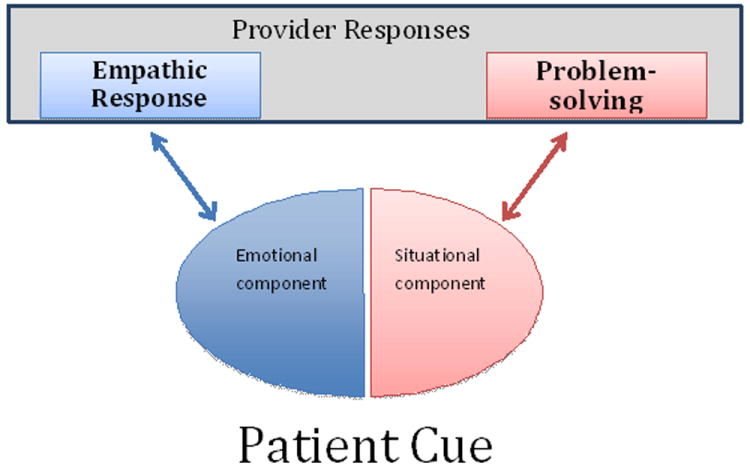

Therefore, empathy and problem-solving both address patient cues, albeit in different capacities. We proposed a model that conceptualizes patient cues as having two components (Figure 2). Patients initially experience a situation or circumstance, such as the death of a loved one or the possibility of cancer, which triggers an emotional response, such as grief or apprehension. Patient cues therefore consist of an underlying situation or event, and the resultant emotion that is conveyed to the provider. This model suggests how “empathic responses” and “problem-solving” may address different aspects of patients’ cues. An “empathic response” is an explicit acknowledgement of the emotional component of the patient’s cue, while “problem-solving” is an implicit acknowledgement of and attempt at addressing the underlying situation.

Figure 2.

Model for provider responses to different components of patient cues.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

Our goal in this study was to better understand the ways in which providers respond to patient cues, if they are not responding empathically. We found providers rarely ignored the patient’s cue entirely, or changed the topic, which is consistent with previous studies by Levinson et al. and Bylund and Makoul (2005),6;8 which found that complete lack of response on providers’ part was uncommon. These findings reflect that when providers miss opportunities to respond empathically, they rarely ignore the patient’s cue altogether; rather, they recognize and acknowledge the patient’s cue but may fail to respond adequately.

“Dismiss/minimize” was similarly an infrequently observed response type. In the two instances we observed, the provider’s response, while clearly devaluing the patient’s concern, could be interpreted as an attempt to reassure the patient. Prior study suggests that reassurance from providers is only perceived as such by patients when it is accompanied by adequate acknowledgement of the patient’s experience. 20 Essentially, even if the provider’s intention is to reassure, the attempt is unsuccessful when the provider does not adequately acknowledge the patient’s concern. The likely interpretation by the patient is denial or dismissal of his concern. In these instances, providers may miss opportunities to respond empathically because they perceive the seriousness of the patient’s situation differently from their patients. Because of this disparity, they proceed to engage in “dismiss/minimize” or reassurance behaviors without acknowledging the patient’s situation or emotions.

“Elicit information” was a common behavior that frequently preceded other responses. “Elicit information” is a facilitative behavior in which providers often go on to explicitly address patients’ cues with “empathic responses” or “problem-solving.” However, in some instances, providers would change the subject (“ignore/change topic”) after gathering information, without ever explicitly addressing the cue. It is unclear how the patient perceives this type of exchange – whether they feel that they have been given a chance to talk, that providers are demonstrating interest or concern, or that the “elicit information” behavior is an adequate, albeit implicit, acknowledgement of their concerns.

We found that often, providers miss opportunities to respond empathically as they are focused on solving the problem underlying the patient’s emotion. As illustrated in Figure 2, patient cues have both situational and emotional components. These two components invite “problem-solving” and “empathic responses,” respectively, as ways to address the two components of a patient’s cue. This understanding is supported by social psychology literature, which draws a distinction between two broad types of social support: emotional (e.g. “empathic response”) and instrumental (“problem-solving”).21 Although both types of support are important, depending on the context,22 emotional support has been regarded as most important to psychological and physical well-being.23;24 Given the frequency of “problem-solving” behavior, the 2-component nature of patient cues, and the importance of emotional support, we suggest that providers might better recognize opportunities to provide empathic responses, and thus emotional support, in addition to instrumental support.

Different types of patient cues might elicit different provider responses and different frequencies of empathic responses.7 As displayed in Table 4, our data support that hypothesis. We found that biomedical concerns and logistical life problems received less empathy and more problem-solving than patient cues concerning death or illness of loved ones and relationship strain. This perhaps reflects the fact that the situational component in relationship strain or death of loved ones is rarely something that can be changed, whereas biomedical concerns and logistical life problems more often have an actionable, or correctable situational component. Furthermore, physicians are trained and socialized to respond in such a way, particularly to biomedical concerns. It is therefore reasonable that “problem-solving” is a more frequent response to logistical life problems and biomedical concerns. However, the emotional distress associated with these types of patient cues may also warrant an empathic response. To the extent that these responses do not come naturally to health professionals, communication skills training programs have been shown to enhance empathic expression.25 We developed a 5-category categorization scheme for provider responses to patients’ emotional cues. The response types “ignore/change topic,” “dismiss/minimize,” and “empathic response,” or analogous response types, have been described in previous literature. “Elicit information” and “problem-solving” were two new categories that we felt better captured aspects of provider response, including meaning, context, provider intent, and effect on patients. For example, if a provider asked a question in response to a patient cue, it could potentially be considered “elicit information” or as “problem-solving,” depending on the context and the provider’s apparent intent.

In contrast to some previous coding schemes, our categorization of provider response allowed for several provider utterances or turns of speech to be grouped together as a single response. Thus, provider responses to patient cues could be understood as a single response behavior or series of discrete, meaningful behaviors. “Problem-solving” is a response type unique to our categorization scheme. Past coding schemes have included similar categories like “information/advise”19 or “pursuit”8 which do not completely reflect the goal-oriented nature of “problem-solving.” Our “problem-solving” category included all utterances interpreted as being part of the troubleshooting or advice-giving process, whether the utterances were questions or statements of advice. “Problem-solving” was a distinct, identifiable, and meaningful unit of behavior, providing important insight into how providers respond to patient cues.

Another unique feature of our analysis was its allowance of multiple provider response types to one patient cue. Especially since our categorization scheme did not dichotomize responses into “positive” or “negative” response types that are mutually exclusive, it was helpful to consider and understand provider responses as having different components and accomplishing more than one aim. A previous study using this type of sequence analysis26 found that empathic responses, which occur rarely, are only offered as the initial response after the patient cue. In our qualitative analysis, we observed instances where empathy was provided immediately after patient cues, but we more frequently saw empathic responses much later in the dialogue surrounding the cue. Often, patients and providers would talk at length about the situation or the emotions (“elicit information”), before the provider would offer an empathic response. For this reason, it is important that studies examining and quantifying empathic responses do not employ premature cutoffs when looking for provider responses.

4.1.1. Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, our categorization scheme required judgment, especially when determining whether certain questions that providers asked should be interpreted as “elicit information” or as part of “problem-solving.” Second, our definition of patient cues was relatively conservative. Previous literature10 suggests that less dramatic expressions of emotion are more likely to be missed by providers, so our study potentially underestimates the true frequency of some response types, particularly “ignore/change topic.” Third, we only considered verbal behaviors in our analysis. Although we did listen to voice tone, providers may convey empathy non-verbally through body language. Lastly, our sample was limited to interactions between HIV-infected patients and their providers. Although the frequency and the types of cues might be distinct in this population, we feel that the provider response patterns we observed are likely to be generalizable.

4.2. Conclusion

Like previous studies, we found that patient emotional cues are common in clinical practice, and that providers miss a substantial number of opportunities to respond empathically when they occur. However, our study goes further to suggest an explanation for this phenomenon. In our analysis, we found that, when not responding empathically, providers often responded by attempting to solve the problem underlying the patient’s emotional experience. This finding suggests that clinicians who do not explicitly acknowledge patient emotions may in fact recognize that the patient is experiencing the emotion, but that they respond by providing instrumental rather than explicit emotional support.

4.3. Practice implications

Although problem-solving about the circumstance around patient emotion is a type of support that could be constructive and helpful for patients, providers should also recognize the importance of providing emotional support, with explicit empathic responses. With this understanding, providers may build stronger therapeutic relationships and achieve better health outcomes with their patients in moments of vulnerability. Future research might aim to better understand whether patients’ preference for emotional or instrumental support differs in different situations or with different emotions, and what effect provider responses have on patient health.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a contract from the Health Resources Service Administration and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ 290-01-0012). In addition, Dr. Korthuis was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (K23 DA019809), Dr. Saha was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Dr. Beach was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K08 HS013903-05) and both Drs. Beach and Saha were supported by Robert Wood Johnson Generalist Physician Faculty Scholars Awards.

Role of the Funding Source. None of the funders had a role in the design and conduct of this analysis, nor was it subject to their final approval.

Appendix

Pathways of Provider Response for 29 Emotional Cues

| Interview | Specific Nature of Cue | Type of Cue | Provider Response Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lost job | Logistical life problem | empathic response --> elicit information |

| 1 | Worry about potential relationship with ex-boyfriend | Family/relationship strain | elicit information --> empathic response --> elicit information |

| 2 | Grandmother passed away | Death/illness of loved one | empathic response --> elicit information |

| 3 | Daughter shoplifting | Family/relationship strain | empathic response --> elicit information --> empathic response |

| 4 | Depression regarding poor appetite | Biomedical cue | dismiss/minimize |

| 4 | Depression regarding HIV+ status, poor self-image | Biomedical cue | problem-solving --> dismiss/minimize |

| 4 | Depression regarding inefficacy of ART | Biomedical cue | ignore/change topic |

| 5 | Possibility of cancer | Biomedical cue | elicit information --> ignore/change topic |

| 6 | Mother sick | Death/illness of loved one | elicit information --> empathic response |

| 7 | Difficulty with having so many providers | Biomedical cue | elicit information --> empathic response --> problem-solving |

| 7 | Difficulty taking care of baby | Family/relationship strain | problem-solving |

| 8 | Frustration w/ erectile dysfunction | Biomedical cue | elicit information --> problem-solving --> empathic response |

| 9 | Aunt passed away | Death/illness of loved one | elicit information --> empathic response |

| 9 | Cannot afford home payments | Logistical life problems (financiall) | elicit information --> problem-solving |

| 10 | Sister passed away | Death/illness of loved one | elicit information --> empathic response |

| 11 | Grandson in gang | Family/relationship strain | elicit information --> empathic response |

| 11 | Apprehension about telling family HIV+ status | Family/relationship strain | problem-solving |

| 12 | Separated with significant other | Family/relationship strain | elicit information --> empathic response |

| 13 | Relationship with a sick friend under stress | Family/relationship strain | elicit information --> empathic response --> problem-solving |

| 14 | Difficulty with raising children | Family/relationship strain | elicit information --> ignore/change topic |

| 15 | Ex-boyfriend taking custody of children | Biomedical cue | elicit information --> ignore/change topic |

| 16 | Brother diagnosed with cancer | Death/illness of loved one | elicit information --> ignore/change topic --> cue raised again --> ignore/change topic |

| 17 | Legal trouble | Logistical life problems (legal) | elicit information --> problem-solving |

| 17 | Unemployed, unable to pay bills | Logistical life problems (financial) | elicit information --> problem-solving --> cue raised again --> elicit information --> problem-solving |

| 18 | Fear about neurological symptoms | Biomedical cue | Ignore/change topic |

| 18 | Grandchildren taken away from daughter’s custody | Family/relationship strain | problem-solving --> elicit information --> empathic response --> problem-solving |

| 19 | Fear of becoming crippled | Biomedical cue | Ignore/change topic |

| 20 | Mother is ill | Death/illness of loved one | problem-solving |

| 21 | Depression regarding disfiguring, disabling Kaposi Sarcoma | Biomedical cue | problem-solving --> cue raised again --> problem-solving --> cue raised again --> problem-solving --> cue raised again--> elicit information --> problem-solving |

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest. None of the authors have any relevant financial conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference list

- 1.Suchman AL, Matthews DA. What makes the patient-doctor relationship therapeutic? Exploring the connexional dimension of medical care. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108:125–130. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-108-1-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellet PS, Maloney MJ. The importance of empathy as an interviewing skill in medicine. JAMA. 1991;266:1831–1832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad Med. 2011;86:359–364. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182086fe1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neumann M, Wirtz M, Bollschweiler E, et al. Determinants and patient-reported long-term outcomes of physician empathy in oncology: a structural equation modelling approach. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;69:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neumann M, Bensing J, Mercer S, Ernstmann N, Ommen O, Pfaff H. Analyzing the “nature” and “specific effectiveness” of clinical empathy: a theoretical overview and contribution towards a theory-based research agenda. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74:339–346. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levinson W, Gorawara-Bhat R, Lamb J. A study of patient clues and physician responses in primary care and surgical settings. JAMA. 2000;284:1021–1027. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.8.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morse DS, Edwardsen EA, Gordon HS. Missed opportunities for interval empathy in lung cancer communication. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1853–1858. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.17.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bylund CL, Makoul G. Examining empathy in medical encounters: an observational study using the empathic communication coding system. Health Commun. 2005;18:123–140. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1802_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bylund CL, Makoul G. Empathic communication and gender in the physician-patient encounter. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48:207–216. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennifer SL, Alexander SC, Pollak KI, et al. Negative emotions in cancer care: do oncologists’ responses depend on severity and type of emotion? Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suchman AL, Markakis K, Beckman HB, Frankel R. A model of empathic communication in the medical interview. JAMA. 1997;277:678–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coulehan JL, Platt FW, Egener B, et al. “Let me see if i have this right…”: words that help build empathy. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:221–227. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-3-200108070-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pollak KI, Arnold RM, Jeffreys AS, et al. Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5748–5752. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beach MC, Saha S, Korthuis PT, et al. Differences in Patient-Provider Communication for Hispanic Compared to Non-Hispanic White Patients in HIV Care. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:682–687. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1310-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beach MC, Saha S, Korthuis PT, et al. Patient-Provider Communication Differs for Black Compared to White HIV-Infected Patients. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:805–811. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9664-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimmermann C, Del PL, Bensing J, et al. Coding patient emotional cues and concerns in medical consultations: the Verona coding definitions of emotional sequences (VR-CoDES) Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? : An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods. 2006;18:59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowen GA. Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: a research note. Qual Health Res. 2012;8:137–152. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Del PL, de HH, Heaven C, et al. Development of the Verona coding definitions of emotional sequences to code health providers’ responses (VR-CoDES-P) to patient cues and concerns. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donovan JL, Blake DR. Qualitative study of interpretation of reassurance among patients attending rheumatology clinics: “just a touch of arthritis, doctor?”. BMJ. 2000;320:541–544. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cutrona C, Russell D. Type of social support and specific stress: Toward a theory of optimal matching. In: Sarason BR, Sarason IG, Pierce GR, Sarason B, Sarason I, Pierce G, editors. Social Support: An Interactional View. New York, NY: John Wiley; 2012. pp. 319–366. [Google Scholar]

- 23.House J, Umberson D, Landis K. Structures and processes of social support. Annual Review of Sociology. 2012;14:293–318. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berkman LF. The role of social relations in health promotion. Psychosom Med. 1995;57:245–254. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199505000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roter DL, Larson S, Shinitzky H, et al. Use of an innovative video feedback technique to enhance communication skills training. Med Educ. 2004;38:145–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2004.01754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Epstein RM, Hadee T, Carroll J, Meldrum SC, Lardner J, Shields CG. “Could this be something serious?” Reassurance, uncertainty, and empathy in response to patients’ expressions of worry. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1731–1739. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0416-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]