Abstract

OBJECTIVE

A theranostic system integrates some form of diagnostic testing to determine the presence of a molecular target for which a specific drug is intended. Molecular imaging serves this diagnostic function and provides powerful means for noninvasively detecting disease. We briefly review the paradigms rooted in nuclear medicine and highlight recent advances in this field. We also explore how nanometersized complexes, called nanomedicines, present an excellent theranostic platform applicable to both drug discovery and clinical use.

CONCLUSION

For imagers, molecular theranostics represents a powerful emerging platform that intimately couples targeted therapeatic entities with noninvasive imaging that yields information on the presence of defined molecular targets before, during, and after cognate therapy.

Keywords: cancer therapy, molecular imaging, molecular medicine, nanomedicine, theranostics

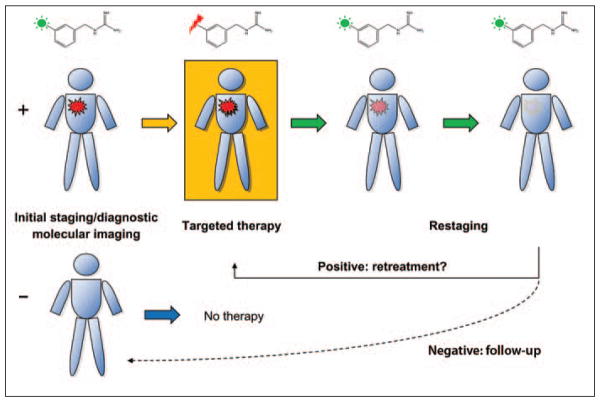

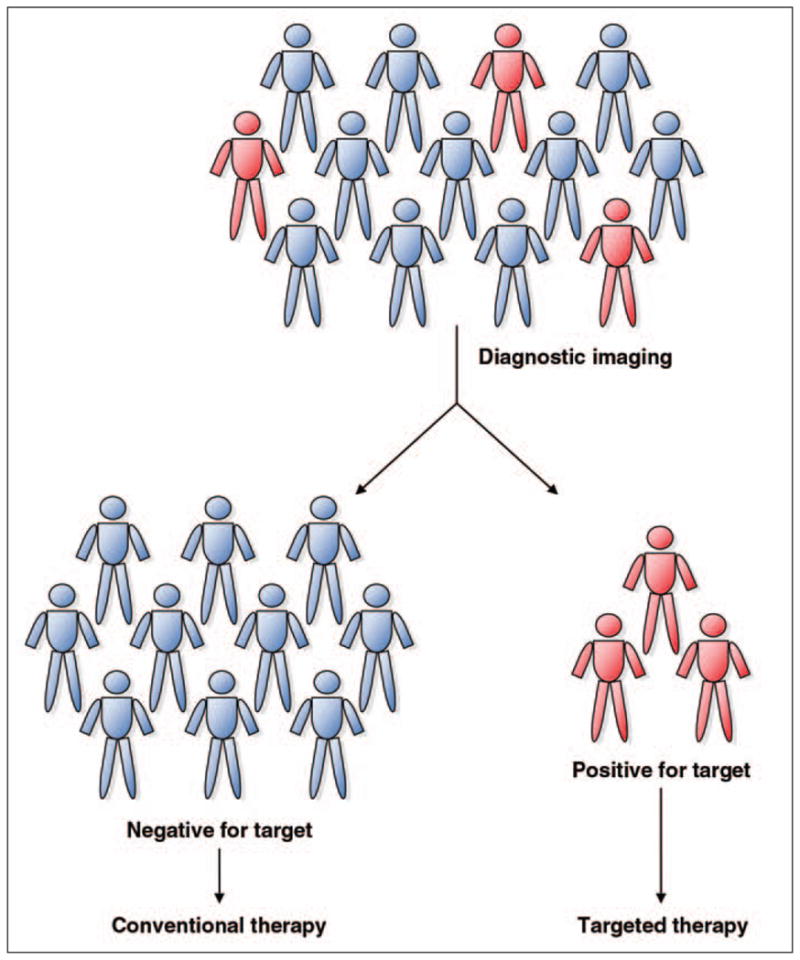

What exactly is “molecular theranostics?” Although open to interpretation, a theranostic approach uses a diagnostic test to determine whether a patient may benefit from a specific therapeutic drug, for example an immunohistochemical test to determine the status of the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) expression in a patient’s breast cancer as a prerequisite for treatment with trastuzumab (Herceptin, Genentech). Hence, a theranostic system couples the therapy with diagnostic information specific for the intended target. For imagers, this diagnostic test can be in the form of an imaging study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Diagram shows how theranostic systems combine diagnostic tests, in this case, imaging, to detect presence of molecular target in each patient. Patients who are found to be positive for molecular target are selected for therapeutic intervention.

Nuclear medicine physicians have practiced this form of combined diagnostic-therapeutic procedures for several decades, exploiting known thyroid-selective properties of radioiodine or using small molecule analogs of norepinephrine or engineered biologics, such as peptides, specific for somatostatin receptor. The term “molecular” is meant to describe active targeting of a specific mechanism important in a particular disease process. Hence, nonactively targeted materials, such as generic blood-pool contrast agents, are not considered true molecular agents. However, this definition remains imprecise, and many variations on this interpretation are possible.

The main reason for the tremendous excitement of theranostics is its revolutionary approach that promises improved therapy selection on the basis of specific molecular features of disease, greater predictive power for adverse effects, and new ways to objectively monitor therapy response. These properties are fundamental elements of personalized medicine. To fully appreciate the direction and future impact of the impending theranostic revolution, the background and basic tenets of this field should be examined.

The latest additions to the armamentarium of multipurpose compositions are nanometersized macromolecular complexes, also called “nanomedicines,” which have inherent features well suited for imaging. We will explore how these new platforms are used for theranostic applications.

The Intimate Role of Molecular Imaging in Theranostics

Imagers use methods that permit noninvasive visualization of physiology utilizing various modalities to characterize anatomic, biochemical, and functional pathology. Ideally, the molecular imaging component of a theranostic system would provide critical diagnostic information for the presence and anatomic location of cellular targets for which a therapeutic agent is intended (Fig. 2). Nuclear medicine physicians are well versed in this concept, which dates back to the mid 1940s with the original use of radioiodine as arguably the earliest imaging-based molecular theranostic agent [1, 2]. Imaging with 123I (a γ-emitter) and combined therapy-imaging with 131I (β and γ emitter) has been the cornerstone of adjunct therapy for differentiated thyroid cancers, and 131I ablative therapy may even be curative in metastatic disease. However, it is well known that dedifferentiated or anaplastic thyroid cancer subtypes with poor iodine avidity respond poorly with 131I, poignantly exemplifying the need for active targeting—a key feature and important recurring theme in this article.

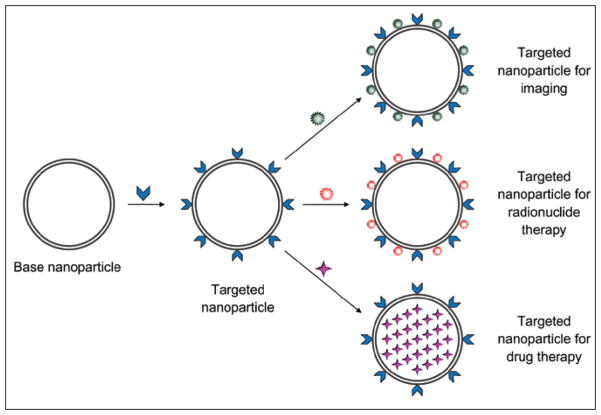

Fig. 2.

Diagram shows example of single-entity theranostic system that combines initial staging with imaging version of specific probe (green sunburst as active moiety) followed by therapy with therapeutic version of imaging probe (red lightning bolt). Restaging examinations at follow-up are performed with imaging probe. Patients with positive imaging results (red lesion) can be treated with therapeutic agent. Patients with negative results will not be treated with targeted agent. Organic molecule structure used in this example is that of metaiodobenzylguanidine with 123I for imaging and 131I for therapy-imaging.

Aside from elemental iodine, another clear example of a single-entity theranostic system is the norepinephrine analog, metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) conjugated to 131I. This small molecule, which was initially reported in early to mid 1980s, serves two distinct roles in diagnostic nuclear imaging and therapy [3, 4]. Although MIBG is used only for diagnostic purposes in the United States, this same agent is approved and routinely available for targeted therapy of neuroendocrine tumors in adults and neuroblastoma in pediatric patients in Europe [5–7]. Its utility and effectiveness appear to be comparable to conventional systemic therapy with fewer and predictable adverse effects [5]. There are other examples that exemplify this fundamental nuclear medicine paradigm, such as somatostatin peptide analogs used in both imaging and radionuclide-based therapy, currently in clinical trials [8–10]. These single-entity imaging agents with therapeutic potential are made possible by the radionuclides attached to them, a distinct advantage for but not exclusive to organic radiopharmaceuticals as we will discuss in the section on nanomedicines.

Currently practiced molecular imaging in the form of PET with the 18F-labeled glucose analog, FDG, has revolutionized medicine, most significantly in oncology. The role of FDG PET, now synonymous with molecular imaging, has become an integral part of patient management for cancer staging, restaging, and monitoring therapy response for a number of reimbursable indications [11]. This development is not surprising because of the valuable mechanistic information derived from FDG PET that provides semi-quantitative information on the enhanced glycolytic mechanism of tumors, also known as the Warburg effect [12]. Although imaging with this sugar analog is relatively nonspecific with regard to differentiating between malignancy and inflammation, there is a large body of evidence in the scientific literature and collective clinical experience that permits remarkable diagnostic accuracy. More important, the value of PET as a clinical decision-making tool has been clearly shown [13–15].

Diagnostic accuracy has been further refined by the technical combination with anatomic imaging in the form of in-line PET/CT, which constitutes virtually all of the PET scanners manufactured and sold today [11]. Part of the success of FDG PET also stems from its nononcologic applications in neurodegenerative disorders, myocardial pathophysiology, and even infection-inflammation imaging [16–18]. However, because FDG accumulation reflects the rate of glucose metabolism, PET does not necessarily reveal any specific information with regard to the presence of a cellular target for which a given drug may be intended, such as a growth factor receptor. Hence, this use of FDG PET does not fully exemplify a specific theranostic platform because imaging and therapeutic agents do not converge on a targeted molecular mechanism. Nonetheless the application of FDG as a surrogate biomarker is clinically useful and provides a generalized approach for disease characterization and therapy monitoring [19].

Numerous other examples of paired molecular imaging-therapy are found with other radiopharmaceuticals that are selective for biochemical processes, such as cellular proliferation, steroid synthesis, growth factor receptor expression, catecholamine production, hypoxia-induced gene expression, or apoptosis. A comprehensive review of theranostic targets is beyond the scope of this article, and the reader is referred to reviews in related subjects by Mankoff et al. [20] and Del Vecchio et al. [21]. A good example of an imaging probe designed for a specific tumor feature is exemplified by 18F-labeled estradiol, which is able to noninvasively identify estrogen receptor–positive lesions by PET [22, 23]. Using this same probe, quantitative PET accurately predicted response to hormonal therapy with tamoxifen [24]. If the decision for hormonal therapy is directly dependent on the imaging findings, this would constitute a true theranostic system.

One of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved radioimmunotherapies for B-cell lymphoma requires the use of imaging before the administration of the 90Y-labeled monoclonal antibody (ibritumomab tiuxetan) to screen for abnormal biodistribution; tumor targeting or quantification are not required to proceed with therapy [25]. This initial imaging agent that utilizes essentially the same therapeutic monoclonal antibody may not exactly fulfill the requisites for a molecular theranostic but provides a basic regulatory framework for incorporating dedicated imaging with therapeutic intervention, particularly at the early stages of drug development. In extending this approach to generate a complete platform for identifying and potentially quantifying targets using a new molecular entity, an attractive paradigm for drug discovery and development emerges.

Applying Traditional nuclear Medicine Paradigms to New Transforming Technologies

Molecular imaging, which is dominated by scintigraphy-based modalities, provides an analytic tool for detecting the presence of neoplastic targets with exquisite sensitivity and relatively high specificity. Theranostics can leverage these nuclear medicine strengths to develop platforms for identifying new biologic targets, predict possible off-target effects, and provide practical means for objective and quantifiable criteria as endpoints in monitoring therapy response. These promising attributes can potentially revolutionize the drug discovery process and dramatically shorten the research and development cycle. Drugs of most chemical or even inorganic compositions that are designed to be specific for a cellular or biochemical target may be rendered into an imaging agent by the appropriate conjugation with imaging radionuclides or other components that can be detected, such as paramagnetic and superparamagnetic metals or optically active compounds. This key concept also underscores the value of the latest generation of potentially transformative biomedical materials that are scaled at the nanometer level.

Nanoparticles represent an ideally suited theranostic platform predominantly because of their modular construction. Biodistribution of all nanoparticulate materials is strongly influenced by their overall size, which restricts them predominantly to the intravascular compartment and surface properties that determine their interaction with the mononuclear phagocyte system and thus their plasma half-life. Passive accumulation of nanoparticles at tumor sites occurs through variably leaky neovasculature, a process also known as the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. This effect alone is sufficient to favorably alter biodistribution to improve the therapeutic efficacy of antineoplastic agents encapsulated within nanostructures, as exemplified by the classic liposomal formulation of doxorubicin (Doxil, Centocor Ortho Biotech Products), which has been clinically used since its FDA approval in 1995. In combination with methods or mechanisms that allow selective drug release, nanomedicines have the ability to deliver and deposit small molecular agents at desired sites of disease. Although still in early phases of development, nanoparticles represent promising new platforms for clinical translation, particularly for cancer.

The New Frontier of Theranostic nanomedicines

Nanomedicines are nanoparticle-based therapeutics, typically between 10 and 200 nm in size and are composed of a variety of organic or inorganic materials, including lipids, polymers, metals, and semiconductors. Nanomedicines offer several distinct advantages, including the ability to carry targeting agents, imaging moieties (including metals or fluorochromes), and drugs in structural configurations not readily possible with traditional small organic molecules. The nanostructure itself can constitute the biologically active complex or it may carry separate entity drugs at relatively high local concentrations. Nanoparticle vehicles can accommodate a wide variety of drug compositions, potentially enabling the use of drug candidates that have been shelved because of solubility or pharmacokinetic reasons. In addition to small organic molecules, other materials such as small interfering RNAs and genes or even peptides can potentially be delivered via nanocarriers. Numerous examples of novel theranostic nanomedicines are reported in the recent literature, and a comprehensive review is outside the scope of this article. The reader is referred to several reviews on the subject by notable leaders in the field [26–29]. These nanostructures and their methods of synthesis, some of which borrow from industrial manufacturing processes such as those of semiconductors, allude to what may be considered nanometersized machines with discrete functional components.

For illustrative purposes, a theranostic nanomedicine suitable for imaging regardless of composition, size, or shape, can be grouped into two general types: untargeted or targeted. As introduced previously, the currently FDA-approved nanoparticle therapies fall into the first category, which basically relies on the EPR effect. Targeting can be achieved by a number of methods, including the use of specific chemical or biologic ligands, as we will describe. Targeted nanomedicines remain the subject of highly active research, particularly for cancer-related molecular targets and are likely to enter clinical trials in the near future.

Early-generation nanomedicines took the form of liposome-encapsulated drugs. The classic example, Doxil (Caelyx outside of the United States), clearly showed how reformulation of an existing drug can alter its distribution and hence its toxicity profile. Despite the benefit of reduced cardiotoxicity associated with unmodified doxorubicin, new toxicities were observed, such as palmoplantar erythrodysesthesia (PPE) [30]. Other doxorubicin liposomal formulations (Myocet, Enzon Pharmaceuticals, approved in Europe and Canada) with modified surfaces eliminated PPE while maintaining reduced cardiotoxicity compared with the parent drug [31]. Other examples of nanomedicines that alter a parent drug’s biodistribution, pharmacokinetics, and toxicities are well reviewed by Davis et al. [29]. All of the currently nanomedicines rely on the EPR effect, and no integrated imaging component is provided as part of their use. Hence, they do not represent examples of true theranostics and are best described as passive nanomedicines.

However, adaptation of liposome technology to an actively targeted theranostic agent can be achieved by engineering such materials with ligands specific for a cellular receptor and another moiety for chelation of radiometals. The resulting single-entity macromolecular theranostic agent has shown promise in targeted imaging and therapy in preclinical models using a targeting moiety specific for certain cell surface receptors overexpressed in tumor-induced angiogenesis [32–34]. This particular macromolecular complex size was approximately 80–100 nm, with biodistribution and pharmacokinetic properties expected of long-circulating liposomes and improved tumor accumulation rates relative to untargeted nanoparticles.

One method for converting a purely imaging probe into a single-entity theranostic agent is by simply switching the radionuclide from a γ-emitter (111In) to a β-emitter (90Y); this is possible with probes that have suitable chelators for such radiometals. This same agent may also be used for evaluating therapeutic response by noninvasive detection of the intended targets. The basic paradigm is represented in Figure 3, which shows a hypothetical theranostic agent equipped with imaging or therapeutic moieties (in this case, radionuclides as well as other drugs). If the diagnostic scan is positive for the presence of the target (e.g., cellular receptor), the patient can be treated with the therapeutic agent and subsequently followed by diagnostic imaging to detect the presence or absence of diseased tissue. An impressive clinical example of this approach using a somatostatin-peptide analog conjugated to 177Lu was published by Gabriel et al. [35]. Because 177Lu emits both γ and β particles, useful for imaging and therapy, respectively, this radionuclide converts the peptide into a true single-entity theranostic agent. Conventional molecular imaging with generic tracers (e.g., FDG) can also be performed for further characterization.

Fig. 3.

Diagram shows hypothetical nanomedicine theranostic platform. Biocompatible base nanoparticle may be synthesized from variety of compositions and production methods. To confer targeting for specific cellular receptor or other molecular feature of diseased tissue, ligands are conjugated to nanoparticle, typically in multivalent manner. Ligands (blue arrowheads) can be small organic molecules, monoclonal antibodies, aptamers, peptides, proteins, or other compatible materials. Diagnostic molecular imaging capabilities can be conferred simply by conjugation of certain agents (green starburst) suitable for detection, such as radionuclides or paramagnetic-superparamagnetic metals. In some configurations, cytotoxic radionuclide (red starburst) may be substituted for imaging radiometal. Alternatively drugs of wide variety of compositions (purple 4-point star) may be encapsulated within nanoparticle structure.

Optimizing pharmacokinetics and biodistribution, particularly with respect to the mononuclear phagocyte system (also called the reticuloendothelial system of the liver, spleen, and bone marrow), remains a major challenge for all nanoparticulate theranostics. The distinct advantage of single-entity theranostics is the ability to determine the specific pharmacokinetic parameters and biodistribution directly from the imaging results. Several strategies for overcoming these limitations are possible including the incorporation of activation schemes with or without targeting. Probes that report through the action of an enzyme overexpressed by tumors, such as proteases, have had remarkable success for optical imaging [36–40] and have been incorporated into nanoparticle platforms [41–44]. Other approaches use exogenous methods such as light, heat, and ultrasound to trigger drug release [45–57].

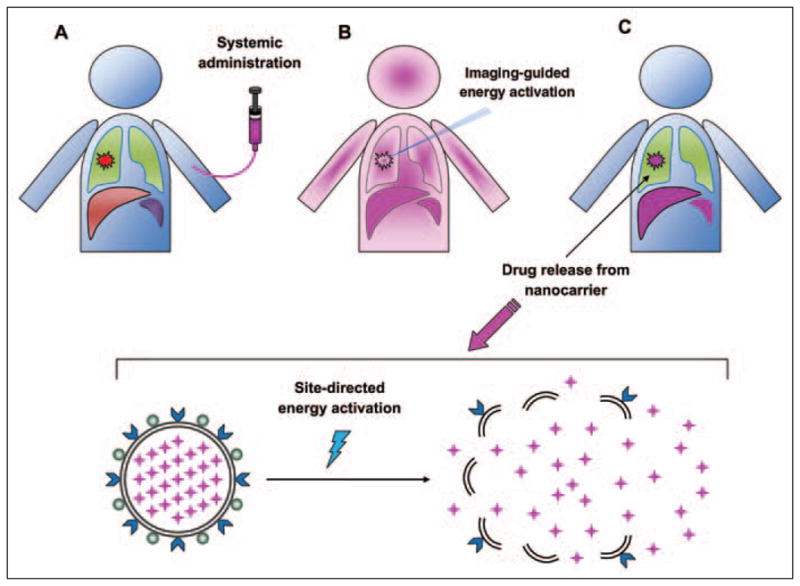

In a modular design using a complex of two types of nanoparticles—one encapsulating an imaging agent or drug and the other a gold nanoparticle tuned for a certain wavelength of light (via plasmon resonance), Qin and coworkers [58] showed that laser energy can trigger nearly instantaneous release of encapsulated contents. When coupled with targeting, this type of theranostic system may provide a suitable platform for remotely controlled site-directed drug release. Attractive opportunities in controllable theranostic platforms raise the demand for biocompatible nanomaterials and appropriate functionalization to effectively target and control the delivery of desired compounds as illustrated in Figure 4. Although antineoplastic applications are the most intensely sought, other fields can also benefit from this approach, such as immunology, cardiology, and infectious diseases. Multifunctional theranostic nanomedicines may indeed revolutionize the drug discovery process and dramatically alter how modern medicine may be practiced in the future.

Fig. 4.

Remotely activated drug release from targeted nanoparticles (although active targeting is optional in this approach).

A, Diagram shows nanomedicine (purple ) intravenously administered to patient with lung tumor (red lesion).

B, After a period of time to maximize tumor accumulation (determined by diagnostic molecular imaging), activation energy (blue rays) is applied to site of disease by imaging-guidance.

C, Activation energy causes release of drugs encapsulated in the nanocarrier elaborated in lower panel. Notice that after systemic administration, pharmacokinetics and biodistribution will be determined by physical properties of nanoparticles, including size and surface charge largely due to interaction with mononuclear phagocyte system (represented by liver and spleen in diagram). Activation step to release drugs at desired sites circumvents some of biodistribution issues of nanomedicines.

Anticipated Impact of Molecular Theranostics

What is the likelihood that molecular theranostics will impact medicine in a tangible way? Although it is difficult to predict the full impact of molecular theranostics in the clinical arena, one may extrapolate from our experience with molecular imaging, particularly of PET. Successful deployment and acceptance of any new medical technology require several key events, including clinical utility, federal regulatory approval, and ultimately coverage from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and third-party payers. This last point raises the issue of economic realities and the hurdles that must be overcome from a commercial development standpoint.

The cost of introducing a diagnostic imaging agent into the market has been estimated to reach up to $200 million (U.S.) [59] and an average cost of over $800 million for therapeutic drugs [60]; and the costs are likely to be higher in the near future. Hence, the downstream payoff for companies investing in new theranostics may never achieve the same level of return as other blockbuster drugs. Although the regulatory hurdle will remain high, judicious use of new microdosing clinical trials [61], also referred to as “phase 0” trials, may reduce the overall cost of screening for commercially viable radionuclide-based theranostics. However the very strength of molecular theranostics will also ironically limit the pool of potential patients who may benefit from any given specific agent. Clearly, for this approach to take foothold, the cost of drug development must be significantly reduced.

How might these new technologies affect the medical professional and particularly imagers? Similar to the introduction of molecular imaging in the form of FDG PET, imagers will need to be adequately proficient in this new technology, but the full practice of therapeutic intervention may also require further specialization within diagnostic radiology or nuclear medicine and perhaps require an entirely separate subspecialty of medicine. Regardless, the landscape of medicine will likely change because future theranosticians will inevitably share or fully adopt the care of patients with diseases that will be molecularly characterized, a requisite step toward individualized medicine.

Conclusions

The goal for this article was to entice the reader to further explore the future of molecular medicine from the standpoint of the imaging professional. Molecular theranostics can be described as a system that integrates a diagnostic test with a therapeutic intervention targeting a molecular feature of disease. Whether exploiting the natural targeting of radioisotopes of iodine or nanometersized macromolecular complexes with built-in drug release mechanisms, the concept of molecular theranostics is familiar for imagers, particularly those with nuclear medicine backgrounds.

Theranostic nanomedicines are promising as single-entity platforms and because of several distinct advantages are attractive for the intrinsic ability to confer imaging that may yield meaningful pharmacokinetic and biodistribution information for the presence of the exact molecular target before, during, and after therapy. Nonetheless, theranostics and particularly nanomedicines are not without limitations, and solutions for many challenges are required to ensure the successful deployment of this exciting new technology. Imagers are poised to take advantage of this revolutionary field by leveraging their traditional role as diagnosticians to fully participate in the practice of personalized molecular medicine.

References

- 1.Hertz S, Roberts A. Radioactive iodine in the study of thyroid physiology; the use of radioactive iodine therapy in hyperthyroidism. J Am Med Assoc. 1946;131:81–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.1946.02870190005002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapman EM, Evans RD. The treatment of hyperthyroidism with radioactive iodine. J Am Med Assoc. 1946;131:86–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.1946.02870190010003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sisson JC, Shapiro B, Beierwaltes WH, Copp JE. Locating pheochromocytomas by scintigraphy using 131I-metaiodobenzylguanidine. CA Cancer J Clin. 1984;34:86–92. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.34.2.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sisson JC, Shapiro B, Beierwaltes WH, et al. Radiopharmaceutical treatment of malignant pheochromocytoma. J Nucl Med. 1984;25:197–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Postema EJ, McEwan AJ. Radioiodinated metaiodobenzylguanidine treatment of neuroendocrine tumors in adults. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2009;24:519–525. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2009.0672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Kraker J, Hoefnagel KA, Verschuur AC, van Eck B, van Santen HM, Caron HN. Iodine-131-metaiodobenzylguanidine as initial induction therapy in stage 4 neuroblastoma patients over 1 year of age. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:551–556. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt M, Simon T, Hero B, Schicha H, Berthold F. The prognostic impact of functional imaging with (123)I-mIBG in patients with stage 4 neuroblastoma >1 year of age on a high-risk treatment protocol: results of the German Neuroblastoma Trial NB97. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1552–1558. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwekkeboom DJ, de Herder WW, van Eijck CH, et al. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy in patients with gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Semin Nucl Med. 2010;40:78–88. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nisa L, Savelli G, Giubbini R. Yttrium-90 DOTA-TOC therapy in GEP-NET and other SST2 expressing tumors: a selected review. Ann Nucl Med. 2011;25:75–85. doi: 10.1007/s12149-010-0444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Essen M, Krenning EP, Kam BL, de Jong M, Valkema R, Kwekkeboom DJ. Peptide-receptor radionuclide therapy for endocrine tumors. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5:382–393. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Czernin J, Benz MR, Allen-Auerbach MS. PET/CT imaging: the incremental value of assessing the glucose metabolic phenotype and the structure of cancers in a single examination. Eur J Radiol. 2010;73:470–480. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelloff GJ, Hoffman JM, Johnson B, et al. Progress and promise of FDG-PET imaging for cancer patient management and oncologic drug development. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2785–2808. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ell PJ. The contribution of PET/CT to improved patient management. Br J Radiol. 2006;79:32–36. doi: 10.1259/bjr/18454286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hillner BE, Siegel BA, Shields AF, et al. The impact of positron emission tomography (PET) on expected management during cancer treatment: findings of the National Oncologic PET Registry. Cancer. 2009;115:410–418. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Höilund-Carlsen PF, Gerke O, Vilstrup MH, et al. PET/CT without capacity limitations: a Danish experience from a European perspective. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:1277–1285. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-2025-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silverman DH. Brain 18F-FDG PET in the diagnosis of neurodegenerative dementias: comparison with perfusion SPECT and with clinical evaluations lacking nuclear imaging. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:594–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petruzzi N, Shanthly N, Thakur M. Recent trends in soft-tissue infection imaging. Semin Nucl Med. 2009;39:115–123. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Segall G. Assessment of myocardial viability by positron emission tomography. Nucl Med Commun. 2002;23:323–330. doi: 10.1097/00006231-200204000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weber WA. Positron emission tomography as an imaging biomarker. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3282–3292. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mankoff DA, Link JM, Linden HM, Sundararajan L, Krohn KA. Tumor receptor imaging. J Nucl Med. 2008;49(suppl 2):149S–163S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Del Vecchio S, Zannetti A, Fonti R, Pace L, Salvatore M. Nuclear imaging in cancer theranostics. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;51:152–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peterson LM, Mankoff DA, Lawton T, et al. Quantitative imaging of estrogen receptor expression in breast cancer with PET and 18F-fluoroestradiol. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:367–374. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.047506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mintun MA, Welch MJ, Siegel BA, et al. Breast cancer: PET imaging of estrogen receptors. Radiology. 1988;169:45–48. doi: 10.1148/radiology.169.1.3262228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linden HM, Stekhova SA, Link JM, et al. Quantitative fluoroestradiol positron emission tomography imaging predicts response to endocrine treatment in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2793–2799. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.3810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spies SM. Imaging and dosing in radioimmunotherapy with yttrium 90 ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin) Semin Nucl Med. 2004;34:10–13. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie J, Lee S, Chen X. Nanoparticle-based theranostic agents. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:1064–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janib SM, Moses AS, MacKay JA. Imaging and drug delivery using theranostic nanoparticles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:1052–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heath JR, Davis ME. Nanotechnology and cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2008;59:251–265. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.59.061506.185523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis ME, Chen ZG, Shin DM. Nanoparticle therapeutics: an emerging treatment modality for cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:771–782. doi: 10.1038/nrd2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Judson I, Radford JA, Harris M, et al. Randomised phase II trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil/Caelyx) versus doxorubicin in the treatment of advanced or metastatic soft tissue sarcoma: a study by the EORTC Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:870–877. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris L, Batist G, Belt R, et al. Liposome-encapsulated doxorubicin compared with conventional doxorubicin in a randomized multicenter trial as first-line therapy of metastatic breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:25–36. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sipkins DA, Cheresh DA, Kazemi MR, Nevin LM, Bednarski MD, Li KC. Detection of tumor angiogenesis in vivo by alphaVbeta3-targeted magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Med. 1998;4:623–626. doi: 10.1038/nm0598-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li L, Wartchow CA, Danthi SN, et al. A novel antiangiogenesis therapy using an integrin antagonist or anti-Flk-1 antibody coated 90Y-labeled nanoparticles. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:1215–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hood JD, Bednarski M, Frausto R, et al. Tumor regression by targeted gene delivery to the neovasculature. Science. 2002;296:2404–2407. doi: 10.1126/science.1070200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gabriel M, Andergassen U, Putzer D, et al. Individualized peptide-related-radionuclide-therapy concept using different radiolabelled somatostatin analogs in advanced cancer patients. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;54:92–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bremer C, Bredow S, Mahmood U, Weissleder R, Tung CH. Optical imaging of matrix metalloproteinase-2 activity in tumors: feasibility study in a mouse model. Radiology. 2001;221:523–529. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2212010368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galande AK, Hilderbrand SA, Weissleder R, Tung CH. Enzyme-targeted fluorescent imaging probes on a multiple antigenic peptide core. J Med Chem. 2006;49:4715–4720. doi: 10.1021/jm051001a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahmood U, Tung CH, Bogdanov A, Jr, Weissleder R. Near-infrared optical imaging of protease activity for tumor detection. Radiology. 1999;213:866–870. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.3.r99dc14866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tung CH, Mahmood U, Bredow S, Weissleder R. In vivo imaging of proteolytic enzyme activity using a novel molecular reporter. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4953–4958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feng X, Lv F, Liu L, et al. Conjugated polymer nanoparticles for drug delivery and imaging. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2010;2:2429–2435. doi: 10.1021/am100435k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mu CJ, Lavan DA, Langer RS, Zetter BR. Self-assembled gold nanoparticle molecular probes for detecting proteolytic activity in vivo. ACS Nano. 2010;4:1511–1520. doi: 10.1021/nn9017334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Josephson L, Kircher MF, Mahmood U, Tang Y, Weissleder R. Near-infrared fluorescent nanoparticles as combined MR/optical imaging probes. Bioconjug Chem. 2002;13:554–560. doi: 10.1021/bc015555d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yao H, Zhang Y, Xiao F, Xia Z, Rao J. Quantum dot/bioluminescence resonance energy transfer based highly sensitive detection of proteases. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46:4346–4349. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Calderon M, Quadir MA, Strumia M, Haag R. Functional dendritic polymer architectures as stimuli-responsive nanocarriers. Biochimie. 2010;92:1242–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Febvay S, Marini DM, Belcher AM, Clapham DE. Targeted cytosolic delivery of cell-impermeable compounds by nanoparticle-mediated, light-triggered endosome disruption. Nano Lett. 2010;10:2211–2219. doi: 10.1021/nl101157z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yague C, Arruebo M, Santamaria J. NIR-enhanced drug release from porous Au/SiO2 nanoparticles. Chem Commun (Camb) 2010;46:7513–7515. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01897j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rai P, Mallidi S, Zheng X, et al. Development and applications of photo-triggered theranostic agents. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:1094–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choi SK, Thomas T, Li MH, Kotlyar A, Desai A, Baker JR., Jr Light-controlled release of caged doxorubicin from folate receptor-targeting PAMAM dendrimer nanoconjugate. Chem Commun (Camb) 2010;46:2632–2634. doi: 10.1039/b927215c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pissuwan D, Niidome T, Cortie MB. The forthcoming applications of gold nanoparticles in drug and gene delivery systems. J Control Release. 2011;149:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rahimi M, Meletis EI, You S, Nguyen K. Formulation and characterization of novel temperature sensitive polymer-coated magnetic nanoparticles. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2010;10:6072–6081. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2010.2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rapoport N, Gao Z, Kennedy A. Multifunctional nanoparticles for combining ultrasonic tumor imaging and targeted chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1095–1106. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rapoport NY, Kennedy AM, Shea JE, Scaife CL, Nam KH. Controlled and targeted tumor chemotherapy by ultrasound-activated nanoemulsions/microbubbles. J Control Release. 2009;138:268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen D, Wu J. An in vitro feasibility study of controlled drug release from encapsulated nanometer liposomes using high intensity focused ultrasound. Ultrasonics. 2010;50:744–749. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Negussie AH, Miller JL, Reddy G, Drake SK, Wood BJ, Dreher MR. Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of cyclic NGR peptide targeted thermally sensitive liposome. J Control Release. 2010;143:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pradhan P, Giri J, Rieken F, et al. Targeted temperature sensitive magnetic liposomes for thermochemotherapy. J Control Release. 2010;142:108–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Staruch R, Chopra R, Hynynen K. Localised drug release using MRI-controlled focused ultrasound hyperthermia. Int J Hyperthermia. 2011;27:156–171. doi: 10.3109/02656736.2010.518198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tagami T, Ernsting MJ, Li SD. Efficient tumor regression by a single and low dose treatment with a novel and enhanced formulation of thermosensitive liposomal doxorubicin. J Control Release. 2011;152:303–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qin G, Li Z, Xia R, et al. Stable partially polymerized liposomes with gold nanoparticle tags for remote controlled release by light. Nanotechnology. 2011 doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/22/15/155605. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nunn AD. The cost of developing imaging agents for routine clinical use. Invest Radiol. 2006;41:206–212. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000191370.52737.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Adams CP, Brantner VV. Estimating the cost of new drug development: is it really 802 million dollars? Health Aff (Millwood) 2006;25:420–428. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bergström M, Grahnen A, Langstrom B. Positron emission tomography microdosing: a new concept with application in tracer and early clinical drug development. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;59:357–366. doi: 10.1007/s00228-003-0643-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]