Thomas Wolfe (Figure 1), regarded as one of the greatest novelists of the 20th century, died in 1938 at the age of 37 of tuberculosis (TB) of the brain. Other great literary figures afflicted with TB include John Keats, Percy Shelley, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Robert Louis Stevenson, Henry David Thoreau, Emily and Charlotte Bronte, Anton Chekov, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. TB was called the “artist's disease” and was linked with creativity and the bohemian life. The TB sufferer was a wanderer in search of a healthy place, and the disease provided people with a reason to travel.

Figure 1.

Thomas Wolfe in his 30s. Photo: The Thomas Wolfe Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, NC.

In 1900, the year of Wolfe's birth, TB was the most dreaded disease throughout the world and was the leading cause of death in the United States. The “climatic theory” of treating lung disease, which originated in Germany and Switzerland, proposed that altitude, atmosphere, and the climate of cool mountain air would help cure the disease of TB, also called the White Plague. Wolfe's hometown of Asheville, North Carolina—which offered the best combination of altitude, atmosphere, and climate—had become a world center for the treatment of TB. Because of this, thousands of TB victims came to Asheville, including George Vanderbilt and E. W. Grove, who contributed to the building of the Biltmore House and the Grove Park Inn, respectively. At the end of the 19th century, it was reported that there were 25 TB specialists in Asheville; many came first as patients to be treated for TB. Between 1900 and 1930, over 25 TB sanitariums were established, but most patients stayed in boarding houses with lower rates of $5 to $15 per week. The houses, which had open air sleeping porches as a necessity, were operated solely for the care of TB patients. The number of boarding houses rose from 55 in 1900 to 137 in 1910.

Thomas Wolfe's mother, Julia, had a keen business sense and in 1906 purchased a 29-room boarding house in downtown Asheville called the Old Kentucky Home located near the family home (Figure 2). Young Tom eventually moved into the boarding house permanently for about 10 years. Thus, Tom was probably exposed to TB in his mother's boarding house while growing up.

Figure 2.

Thomas Wolfe in front of the Old Kentucky Home at 48 Spruce Street, Asheville, NC, about 1906. Photo: North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, with permission of the Estate of Thomas Wolfe.

Wolfe wrote much about diseases, especially TB, in his autobiographical masterpiece, Look Homeward Angel, and it is believed he had a fear of TB, which haunted him and affected his writing long before the discovery of the tubercular lesion in his right lung in 1938. In a letter to his mother in 1920, he wrote about his “heavy cold and the rattling cough” that brought pain to his right lung and a spot of blood on his handkerchief.

Tom was only 15 when he enrolled at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. He went there alone with no connections or close friends. Described as a “green freshman,” obscure and lonely, he would become a prominent and popular campus figure by his junior year. Outside the classroom, he pursued numerous activities and “joined everything.” He was editor of the college newspaper, The Tar Heel; wrote stories, plays, and poems for the university magazine; and was associate editor of the college annual, Yackety Yak. Active in formal debate, Wolfe later joined the Carolina Playmakers, and in 1919, his one-act play, “The Return of Buck Gavin,” was given its premier, with the author appearing as the mountain outlaw of the title. He was selected to the Golden Fleece honor society and was a member of Pi Kappa Phi social fraternity at the University of North Carolina (Figure 3). At the end of his senior yearbook entry, the following quote appeared: “He can do more between 8:25 and 8:30 than the rest of us can do all day, and it is no wonder that he is classed as a ‘genius.’”

Figure 3.

Thomas Wolfe (center) and two other students at the Pi Kappa Phi fraternity house. Photo: North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

After graduation, Tom enrolled at Harvard and eventually ended up teaching and writing in New York City. He made several trips to Europe. His first novel, Look Homeward Angel, was published in 1929. Of Time and the River followed in 1935 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Working on the manuscript for Of Time and the River in his Brooklyn apartment in 1935. Photo: The Thomas Wolfe Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, NC.

THE TRIP WEST AND WOLFE'S LAST ILLNESS

In early 1938, Wolfe began intensive work on his new novel. As usual, he eventually produced a huge manuscript totaling more than 4000 typewritten pages and containing over 1.2 million words. His editor later prepared it for posthumous publication as three separate books, The Web and the Rock, You Can't Go Home Again, and The Hills Beyond.

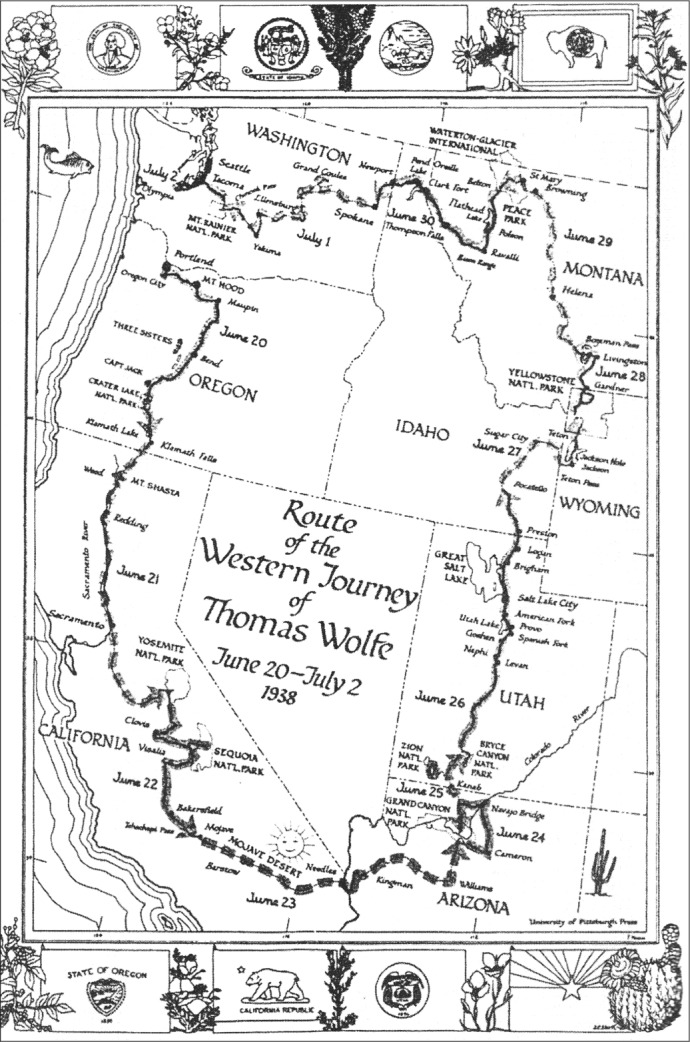

In May to June 1938, Thomas Wolfe embarked on a western vacation trip (Figure 5). Arriving in Portland, Oregon, in June, he was invited to join an experiment in tourism by the editor of the Portland newspaper. He agreed to make the trip by car with the editor and one other man to publicize the accessibility and inexpensiveness of the national parks in the western United States. It was an incredible “whirlwind” trip over a 2-week period, and the three men covered 4500 miles and visited 11 national parks, including Crater Lake, Yosemite, Sequoia, Grand Canyon, Bryce Canyon, Zion, Grand Teton, Yellowstone, and Glacier national parks (Figure 6). Wolfe rode in the back seat of the car and recorded his impressions daily, producing a journal of approximately 12,000 words. By the time the journey ended at Mt. Rainier on July 2, all three men were very tired. Wolfe caught a bus for Seattle.

Figure 5.

A map of Wolfe's western journey. Photo: University of Pittsburgh Press.

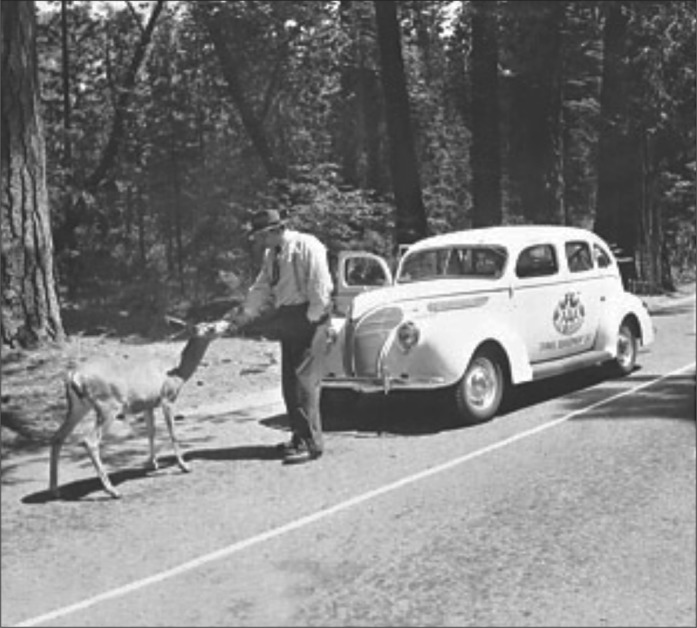

Figure 6.

Feeding a deer in Yosemite National Park, California, 1938. Photo: North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, with permission of the Estate of Thomas Wolfe.

Four days later, he developed an illness suggestive of pneumonia with cough, fever, and congestion. He was examined by a friend's family physician, Dr. Edward Ruge, and placed in a private sanitarium. He remained under Dr. Ruge's care for about 1 month, with treatment consisting of diathermy, cough suppressants, and complete rest—the only measures used to treat pneumonia in that preantibiotic era. He did seem to improve initially; a pulmonary consultant was called in and agreed that he seemed to be making good progress.

His cough lingered for several weeks, however, and he continued to be febrile. Later, in early August 1938, he began to experience excruciatingly painful headaches. Under pressure from his brother Fred (from Spartanburg, SC) who visited Wolfe, and from his publisher Edward Aswell, he was taken to Providence Hospital in Seattle where, on August 6, a chest x-ray was taken. This showed a large area of consolidation in the right upper lobe. TB was then first considered as a possible diagnosis.

This suggestion terrified Wolfe, as he had always feared TB. He dismissed Dr. Ruge and put himself under the care of Dr. Charles Watts, the principal lung specialist in the Providence Hospital in Seattle. He remained in the hospital the rest of August. Dr. Watts felt that Wolfe had pneumonia, not TB, and Wolfe and his brother Fred seemed relieved. However, the headaches increased in severity, and morphine was administered so that he could sleep. It was said that his head was rubbed with witch hazel every night until he was “virtually drenched.”

WOLFE'S FINAL DAYS

On September 4, 1938, Wolfe was found to be disoriented and confused. Dr. Watts performed a funduscopic examination and described a “choked disk.” He was concerned about the possibility of a metastatic lesion to the brain and told the family: “Certainly this is no ordinary pneumonia.” He urged them to take Wolfe to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore to be examined by Dr. Walter Dandy, described as “the best brain surgeon in the United States.”

About this time, a neurosurgeon from Seattle, Dr. George Swift, examined Wolfe and diagnosed “brain abscess, which might or might not be tubercular in origin,” and also urged the family to get him to Baltimore as quickly as possible. The next day, Wolfe, accompanied by his sister Mabel and a nurse, boarded the train for a 5-day trip east. Morphine was given to reduce his headaches during the journey. He was described as being delirious on the first night of the journey. At Chicago, he was met by his mother.

He arrived in Baltimore on September 10, 1938, and was immediately admitted to Johns Hopkins Hospital. He was examined by Dr. Dandy, who felt that he was “desperately ill.” After careful evaluation, it was concluded that Wolfe was most likely suffering from acute pulmonary TB with a cerebral tubercle or possible tuberculous meningitis. Metastatic cancer or a cerebral abscess were also in the differential diagnosis.

Dandy recommended a trephining procedure to decrease the pressure on the brain. When this emergency operation was performed, fluid “spurted with terrific pressure, shooting 3 feet into the air,” but this operation only gave temporary relief. Major surgery was performed on September 12 and consisted of a 2-hour cerebellar exploration, looking for a large tubercle that might be causing the hydrocephalus. Unfortunately, Dr. Dandy discovered “myriads of tubercles” throughout the meninges. The medical report of the operation read, “Obviously nothing could be done,” and the wound was closed. Wolfe never regained consciousness and died on September 15, 1938, just 18 days short of his 38th birthday. He was buried in Asheville in Riverside Cemetery.

It is ironic that Wolfe died so young, as an early death was always on his mind. Because of this, he thought he could never write down all that he had to write. He was truly obsessed with writing. Even when exhausted, he thought only of the time when he would be writing again. In the 12 years between the time he began to write Look Homeward Angel in 1926 and his death in 1938, Wolfe turned out literally millions of words—a record few American writers can match.

SELECTED REFERENCES

- Stephens I. Asheville: the tuberculosis era. North Carolina Medical Journal. 1985;46:455–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe T, editor; Bruccoli MJ, editor; Magi AP, editor. The Magical Campus: University of North Carolina Writings, 1917–1920. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell T. Thomas Wolfe: An Illustrated Biography. New York: Pegasus; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mauldin JM. Thomas Wolfe: When Do the Atrocities Begin. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lathan SR. The death of Thomas Wolfe: a 60-year retrospective. J Med Assoc Ga. 1998;87(3):214–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AM. Neurosurgical genius: Walter Edgar Dandy. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1994;135(5):358–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]